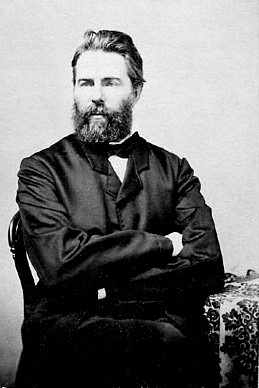

“…getting the ship under weigh…”: A Political Companion to Herman Melville

by Trisha Brady

~

Critical interpretations addressing the political content of Herman Melville’s works are often traced back to the 1960s and the scholarship of Alan Heimert, Charles Foster, and Willie Weathers who wrote on Moby-Dick (1851). Current scholars, including those anthologized in Jason Frank’s A Political Companion to Herman Melville (2013), cannot resist pursuing Melville’s oeuvre in ways that make Melville and the political questions raised by his texts present for readers today. But, what comes of these endeavors? One only has to consider Andrew Delbanco’s Melville: His World and Work (2005) to find an answer. Referring to Benjamin Barber’s comment on Benito Cereno, Delbanco writes: “Today, one recognizes in Benito Cereno a prophetic vision of … ‘American innocence so opaque in the face of evil that it seems equally insensible to slavery and the rebellion against slavery’—the kind of moral opacity that seems still to afflict America as it lumbers through the world creating enemies whose enmity it does not begin to understand”.1 Delbanco, here, makes an indirect critique of an America lumbering under the foreign policy of George W. Bush and his administration that reveals his own preoccupations while writing his book, preoccupations that are clearly outlined in the introduction and in his discussion of references to Moby-Dick made by the late Edward Said and others who were critical of the Bush administration’s responses to the 9/11 attacks (Delbanco 13). Whether Melville indicts as Delbanco does is up for discussion, but Delbanco is correct in contending that we, readers and scholars, tend to create “a steady stream of new Melvilles, all of whom seem somehow able to keep up with the preoccupations of the moment …” (Delbanco 12-13). Thus, it is no surprise that Jason Frank quotes C. L. R. James’s notion that Melville’s prophetic vision captures “the world in which we live” (qtd. in Frank 17) in his introduction to A Political Companion to Herman Melville (2013). Frank is aware of the pitfalls of ‘presentism,’ however, and says readers should approach efforts to translate Melville’s work into “clarified and systematic political theory” with skepticism though he contends Melville’s works “provoke us” to contemplate “the pressing issues of our political life,” such as “empire, freedom, race, progress, memory, violence, individualism, democracy, war, and law.”2

In his introduction, Frank notes that this collection of essays on Melville’s fiction and poetry is “dedicated solely to [Melville’s] political thought,” and that the premise for his introduction rests on the notion that “political theory’s neglect of Melville has impoverished our understanding not only of American political thought in the nineteenth century, but of the American political tradition itself” (1-2). I am not certain, however, that political theorists have neglected Melville. One only has to peruse the bibliography of “Works on Melville’s Politics” at the end of the collection to find a lengthy list of criticism by scholars who engage Melville, including but not limited to texts by Gilles Deleuze, Wai Chee Dimock, Donald Pease, and Brook Thomas. Perhaps, Frank feels theorists in the field of Political Science have neglected Melville. If so, this collection addresses that since a majority of the authors included in the collection are professors of politics (Political Science, Political Ethics, and Political Theory).

The collection begins with analyses of Typee (1846) and Omoo (1847) and ends with Billy Budd (1924). The fourteen anthologized essays (and the multiple Melvilles we are presented with) are given a chronological arrangement that follows the order of the publication of Melville’s works. Frank suggests this allows essays discussing the same Melville text to be juxtaposed while also giving readers the ability to note the range and preoccupations of Melville’s works. In addition, several of the authors make direct references to other essays within the collection in an effort to rhetorically shape the volume and make the collection cohere by referring readers to other essays within the collection. George Shulman’s essay entitled “Chasing the Whale: Moby-Dick as Political Theory” aptly represents Frank’s aims for the collection along with the value of Melville’s political thought and use of tragedy when he contends that Moby-Dick creates an “alter-world … a fictional space or place at once related to and removed from ‘reality,’ in which to stage a tragedy—at once modern and American—of democratic dignity” (71). In this sense, Schulman sees Melville’s whale tale as an “artful speech act” as well as “a form of meditation” that engages an audience or readers and allows a political community to reflect upon its “core axioms, constitutive practices, and fateful decisions” (71). Thus, readers’ attempts at meaning-making bind literary art and political theory (See Shulman’s footnote on Wendy Brown’s “At the Edge: The Future of Political Theory” on page 99). And, in this endeavor to interpret, Melville’s readers confront Melville’s attempt “to wrestle with affirmation and the imperatives of action” along with “the dilemmas of human agency in a world of ‘mortal inter-indebtedness’” (Frank 9).

In this endeavor to interpret, Melville’s readers confront Melville’s attempt “to wrestle with affirmation and the imperatives of action” along with “the dilemmas of human agency in a world of ‘mortal inter-indebtedness’” (Frank 9).

Essays by Sophia Mehic, Roger W. Hecht, Shannon L. Mariotti, Lawrie Balfour, Thomas Dumm, and—to an extent—Susan McWilliams further elaborate on Melville as a critic of American traditions and culture that threaten democracy. The essays in the collection do not skirt the debates and tensions that marked American politics and culture in the nineteenth century, nor do they all concur with the representation of Melville’s political thoughts put forward by Frank and Shulman. For example, Kennan Ferguson suggests Melville offers readers an American version of colonialism that reifies discourses of conquest and domination. In addition, Roger Berkowitz, Jason Frank, and Jennifer L. Culbert note a growing skepticism regarding the ground for American democratic politics in Melville’s works that encourages readers to critically engage the very paradoxes of the democratic axioms and laws the nation was founded upon. Frank and Culbert reflect upon authoritative relations and the problem of ‘measured forms’ while Berkowitz considers collective loss and sorrow as the condition of possibility for a new ground for national unity that allows for the exchange of feelings and the formation of affective bonds in Melville’s Civil War poetry. And, Kevin Attell’s “Language and Labor, Silence and Stasis: Bartleby among the Philosophers” takes a step in the theoretical direction Melville scholars must explore by summarizing rigorous theoretical engagements with “Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street” (1853) by Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Derrida, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Giorgio Agamben, and Slavoj Žižek.

The collection achieves its aim of engaging Melville’s political contemplations and the ambiguities of his thought although it is largely devoted to analyses of Melville’s major works of fiction. This reader’s main complaint is that the breadth of the collection undermines the editor’s particular aim and focus. Still, the collection offers readers a range of interdisciplinary and critical essays on Melville’s work and should be commended for the various approaches to the political content of Melville’s works. Only two of the essays in the edition were published previously; thus, the essays offer scholars in the field of Melville Studies and theorists “new” essays from a number of academics in Political Science with a few representatives from English and American Studies. This companion attempts to give us a representation of a Melville whose literary and political preoccupations are still relevant because they are encapsulated within narratives that value “dispersal—multiple and overlapping perspectives, movement across surfaces,” and make us question modern notions of progress and its political functions (Frank 64), empire, American liberalism, individualism, and violence.

“Critical and imaginative works,” according to Kenneth Burke, “are answers to questions posed by the situation in which they arose. They are not merely answers, they are strategic … stylized answers,” that “size up the situations, name their structure and outstanding ingredients, and name them in a way that contains an attitude towards them.”3 (1, 3). With Burke’s notion of critical and imaginative works in mind, we can consider Melville’s literature as it represents questions and possible answers to political issues and situations relevant to the American Renaissance. Melville’s particular themes and poetics are private in origin, but this collection sheds light on the imperatives of Melville as writer and the political dimensions of his works, which refract and meditate on the conflicts of the nineteenth-century on a formal and rhetorical level that produces a multiplicity of meanings. The relationship of Melville’s literary art to the political and social world outside of it may remain unresolved or even ambiguous, but in the process of interpretation, we reflect upon our responses to Melville’s political romances. For, as Michael Rogin contends in Subversive Genealogy: The Politics and Art of Herman Melville (1983), the relationship between American politics and American art is one in which “American literature took on critical, political functions in the absence of a realist politics, but that absence … influenced the form of the critical literature itself” so that it “reflected society in a distorting lens” that “generated and exposed social divisions,” even when authors attempted to obscure those divisions (19). 4

__________

Trisha Brady (Ph.D., SUNY, Buffalo) is an Assistant Professor of English Language and Literature at BMCC, CUNY.

__________

1. Delbanco, Andrew. Melville: His World and Work. New York: Vintage, 2006. 242.

Back to essay

2. Frank, Jason, ed. A Political Companion to Herman Melville. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2013. 17.

Back to essay

3. Burke, Kenneth. The Philosophy of Literary Form: Studies in Symbolic Action, 2d ed. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1967. 1,3.

Back to essay

4. Rogin, Michael Paul. Subversive Genealogy: The Politics and Art of Herman Melville. New York: Knopf, 1983. 19.

Back to essay

Leave a Reply