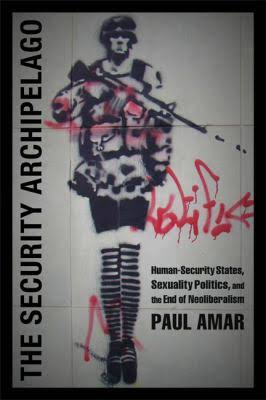

A Review of Paul Amar’s The Security Archipelago: Human-Security States, Sexuality Politics, and the End of Neoliberalism (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2013).

By Neel Ahuja

One of the most widely reported news stories of the 2011 revolution in Egypt involved sexual assaults and other physical attacks on women in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, where mass protests led to the ouster of former President Hosni Mubarak. Paul Amar’s singular book The Security Archipelago explores, among other topics, the Egyptian military council’s attempt to burnish its own authority to “rescue the nation” and its “dignity” by constructing the Arab Spring uprising as a destructive site of violence and moral degradation (3). Mirroring the racialized discourse of international news media who invoked animal metaphors to represent dissent at Tahrir as an articulation of pathological urban violence and frenzy (203), the counter-revolutionary campaign allowed the military to arrest and incarcerate protesters by associating them with demeaned markers of class status and sexuality.

For Amar, this conjunction of moralizing statism and the militarization of social life is indicative of a particular governmental form he calls “human security,” a set of transnational juridical, political, economic, and police practices and discourses that become especially legible in sites of urban crisis and struggle. Amar names four interlocking logics that constitute human security: evangelical humanitarianism, police paramilitarism, juridical personalism, and workerist empowerment (7). He unveils these logics by constructing a dense analysis of security politics linking the megacities of Cairo and Rio de Janiero.

The chapters explore crisis moments that reveal connections between the militarization of police, the development of urban planning and development policy, tourism, the management of labor processes, and racialized and gendered struggles over rights and citizenship. Such connections arise in crises around public protest, attempts by municipal and national authorities to market heritage (in the form of Islamic heritage architecture or samba music) to tourists, coalitions between labor and evangelical Christian groups to combat trafficking and corruption, the attempts of 9/11 plotter Muhammad Atta to develop a theory of Islamic urban planning, and the policing of city space during major international development meetings. These wide-ranging case studies ground the book’s critical security analysis in sites of struggle, making important contributions to the understanding of the spread of urban violence and progressive social policy in Brazil and the rise of left-right coalitions in Islamic urban planning and revolutionary uprisings in Egypt.

Throughout the book, public contestation over the permissible limits of urban sexuality emerges as a key factor inciting securitization. It serves as a marker of cultural tradition, a policed indicator of urban space and capital networking, and a marker of political dissent. For Amar, the new subjects of security “are portrayed as victimized by trafficking, prostituted by ‘cultures of globalization,’ sexually harassed by ‘street’ forms of predatory masculinity, or ‘debauched’ by liberal values” (15). In this way, the “human” at the heart of “human security” is a figure rendered precarious by the public articulation of sexuality with processes of economic and social change.

If this method of transnational scholarship showcases the unique strengths of Amar’s interdisciplinary training, Portuguese and Arabic language skills, and past work as a development specialist, it brilliantly articulates a set of connections between the cities of Rio and Cairo evident in their parallel experiences of neoliberal economic policies, redevelopment, militarization of policing, NGO intervention, and rise as significant “semiperipheral” or “first-third-world” metropoles. In contrast to racialized international relations and conflict studies scholarship that fails continually to break from the mythologies of the clash of civilizations, Amar’s book offers a fascinating analysis of how religious politics, policing, and workerist humanisms interface in the urban crises of two megacities whose representation if often overwritten by stereotyped descriptions of either oriental despotism (Cairo) or tropicalist transgression (Rio).

These cities, in fact, share geographic, economic, and political connections that justify what Amar describes as an archipelagic method: “The practices, norms, and institutional products of [human security] struggles have… traveled across an archipelago, a metaphorical island chain, of what the private security industry calls ‘hotspots’–enclaves of panic and laboratories of control–the most hypervisible of which have emerged in Global South megacities” (15-16). The security archipelago is also a formation that includes but transcends the state; it is “parastatal” and reflects the ways in which states in the Global South, NGO activists, and state attempts to humanize security interventions have produced a set of governmentalities that attempt to incorporate and govern public challenges to austerity politics and militarism.

As such, Amar’s book offers a two-pronged challenge to dominant theories of neoliberalism. First, it clarifies that although many of the wealthy countries still battle over a politics of austerity, the so-called Washington Consensus combining financial deregulation, privatization, and reduction of trade barriers no longer holds sway internationally or even in its spaces of origin. Indeed, Amar claims that even the Beijing Consensus — the turn since the 1990s to a strong state hand in development investment combined with the controlled growth of highly regulated markets — is being supplanted by the parastatal form of the human security regime. Second, this line of thought requires for Amar a methodological shift. Amar claims, “we can envision an end to the term neoliberalism as an overburdened and overextended interpretive lens for scholars” given “the demise, in certain locations and circuits, of a hegemonic set of market-identified subjects, locations, and ideologies of politics” (236). The Security Archipelago offers an alternative to theories of globalization that privilege imperial states as the primary forces governing the production of transnational power dynamics. Without making the common move of romanticizing a static vision of either locality or indigeneity in the conceptualization of resistance to globalization, Amar locates in the semiperiphery a crossroads between the forces of national development and transnational capital. It is in this crossroads where resistances to the violence of austerity are parlayed into new security regimes in the name of the very human endangered by capitalism’s market authoritarianism.

It is notable that the analysis of sexuality, with its attendant moral incitements to security, largely drops out of Amar’s concluding analysis of the debates on the end of neoliberalism. He does mention sexuality when proclaiming a shift from a consuming subject to a worker in the postneoliberal transition: “postneoliberal work centers more on the fashioning of moralization, care, humanization, viable sexualities, and territories that can be occupied. And the worker can see production as the collective work of vigilance and purification, which all too often is embedded through paramilitarization and enforcement practices” (243). While the book expertly reveals the emphasis on emergent forms of moral labor and securitizing care in the public regulation of sexuality, it also documents that moral crises and policing around the sexuality of samba, for example, are layered by the nexus of gentrification, private redevelopment, and transnational tourism that commonly attract the label neoliberalism. This point does not directly undermine Amar’s argument but suggests that further discussion of sexuality’s relation to human security regimes might engender an analytic revision of the notion of postneoliberal transition. The public articulation of sexuality as the site of urban securitization might rather reveal the regeneration of intersecting consumption forms and affective labors of logics of marketization and securitization that are divided geographically but dynamically interrelated.

The fact that Amar’s book raises this problem reveals the significance of the study for moving forward scholarship on sexuality, security, and globality — as individual objects of study and intertwined ones. As scholars focusing, for example, on homonationalist marriage practices in the global north continue to use the analytic frame of neoliberalism, Amar’s study might press for how the moral articulation of the marriage imperative exerts a securitizing force that transcends market logics. Similarly, Amar’s focus on both sexuality and the semiperiphery offer significant geographic and methodological disruptions to the literatures on neoliberalism, the rise of East Asian financial capital, and crisis theory. His unique method challenges interdisciplinary social theorizing to grapple with the archipelagic nature of contemporary forces of social precarity and securitization.

Neel Ahuja is associate professor of postcolonial studies in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at UNC. He is the author the forthcoming Bioinsecurities: Disease Interventions, Empire, and the Government of Species (Duke UP).