By Michelle Moravec

~

Millions of the sex whose names were never known beyond the circles of their own home influences have been as worthy of commendation as those here commemorated. Stars are never seen either through the dense cloud or bright sunshine; but when daylight is withdrawn from a clear sky they tremble forth

— Sarah Josepha Hale, Woman’s Record (1853)

As this poetic quote by Sarah Josepha Hale, nineteenth-century author and influential editor reminds us, context is everything. The challenge, if we wish to write women back into history via Wikipedia, is to figure out how to shift the frame of references so that our stars can shine, since the problem of who precisely is “worthy of commemoration” or in Wikipedia language, who is deemed notable, so often seems to exclude women.

As this poetic quote by Sarah Josepha Hale, nineteenth-century author and influential editor reminds us, context is everything. The challenge, if we wish to write women back into history via Wikipedia, is to figure out how to shift the frame of references so that our stars can shine, since the problem of who precisely is “worthy of commemoration” or in Wikipedia language, who is deemed notable, so often seems to exclude women.

As as Shannon Mattern asked at last year’s Art + Feminism Wikipedia edit-a-thon, “Could Wikipedia embody some alternative to the ‘Great Man Theory’ of how the world works?” Literary scholar Alison Booth, in How To Make It as a Woman, notes that the first book in praise of women by a woman appeared in 1404 (Christine de Pizan’s Book of the City of Ladies), launching a lengthy tradition of “exemplary biographical collections of women.” Booth identified more than 900 volu mes of prosopography published during what might be termed the heyday of the genre, 1830-1940, when the rise of the middle class and increased literacy combined with relatively cheap production of books to make such volumes both practicable and popular. Booth also points out, that lest we consign the genre to the realm of mere curiosity, predating the invention of “women’s history” the compilers, editrixes or authors of these volumes considered them a contribution to “national history” and indeed Booth concludes that the volumes were “indispensable aids in the formation of nationhood.”

mes of prosopography published during what might be termed the heyday of the genre, 1830-1940, when the rise of the middle class and increased literacy combined with relatively cheap production of books to make such volumes both practicable and popular. Booth also points out, that lest we consign the genre to the realm of mere curiosity, predating the invention of “women’s history” the compilers, editrixes or authors of these volumes considered them a contribution to “national history” and indeed Booth concludes that the volumes were “indispensable aids in the formation of nationhood.”

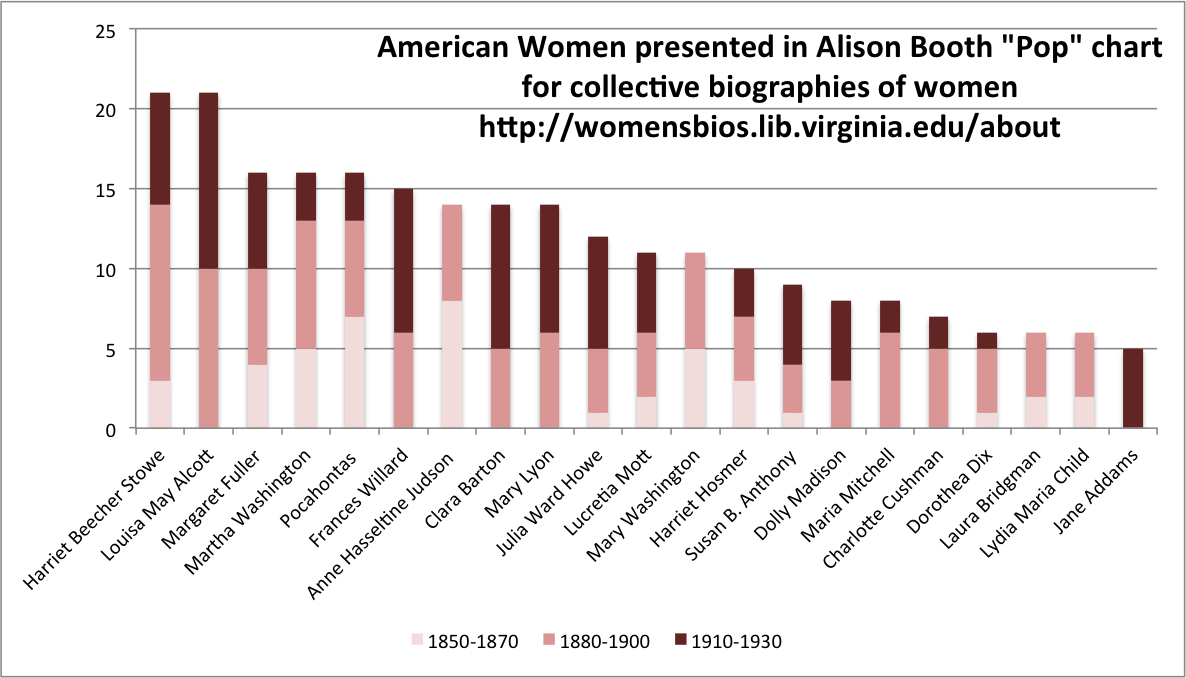

Booth compiled a list of the most frequently mentioned women in a subset of these books and tracked their frequency over time. In an exemplary project, she made this data available on the web, allowing for the creation of the visualization below of American figures on that chart.

This chart makes clear what historians already know, notability is historically specific and contingent, something Wikipedia does not take into account in formulating guidelines that take this to be a stable concept.

Only Pocahontas deviates from the great white woman school of history and she too becomes less salient over time. Furthermore, by the standards of this era, at least as represented by these books, black women were largely considered un-notable. This perhaps explains why, in 1894, Gertrude Mossell published The Work of the Afro-American Woman, a compilation of achievements that she described as “historical in character.” Mossell’s volume itself is a rich source of information of women worthy of commemoration and commendation.

Looking further into the twentieth-century, the successor to this sort of volume is aptly titled, Notable American Women, a three-volume set that while published in 1971 had its roots in the 1950s when Arthur Schlesinger, as head of Radcliffe’s College council, suggested that a biographical dictionary of women might be a useful thing. Perhaps predictably, a publisher could not be secured, so Radcliffe funded the project itself. The question then becomes does inclusion in a volume declaring women as “notable” mean that these women would meet Wikipedia’s “notability” standards?

Studies have found varying degrees of bias in coverage of female figures compared to male figures. The latest numbers I found, as of January 2015, concluded that women constituted only 15.5 percent of the biographical entries on the English Wikipedia, and that prior to the 20th century, the problem was wildly exacerbated by “sourcing and notability issues.” Using the “missing” biographies concept borrowed from a 2010 study of Wikipedia’s “completeness,” I compared selected “classified” areas for biographies of Notable American Women (analysis was conducted by hand with tremendous assistance from Rosalba Ugliuzza).

Working with the digitized copy of Notable American Women in Women and Social Movements, I began compiling a “missing” biographies quotient, the percentage of entries missing for individuals by the “classified list of biographies” that appeared at the end of the third volume of Notable American Women. Mirroring the well-known category issues of Wikipedia, the editors finessed the difficulties of limiting individuals to one area by including them in multiple, including a section called “Negro Women” and another called “Indian Women”:

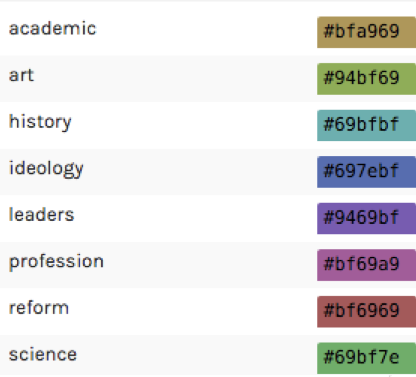

Initially I had suspected that larger classifications might have a greater percentage of missing entries, but that is not true. Social workers, the classification with the highest percentage of missing entries, is a relatively small classification with only nine individuals. The six classifications with no missing entries ranged in size from five to eleven. I then created my own meta-categories to summarize what larger classifications might exacerbate this “missing” biographies problem.

Inclusion in Notable American Women does not translate into inclusion in Wikipedia. Influential individuals associated with female-dominated professions, social work and nursing, are less likely to be considered notable, as are those “leaders” in settlement houses or welfare work or “reformers” like peace advocates. Perhaps due to edit-a-thons or Wikipedians-in-residence, female artists and female scientists have fared quite well. Both Indian Women and Negro Women have the same percentage of missing women.

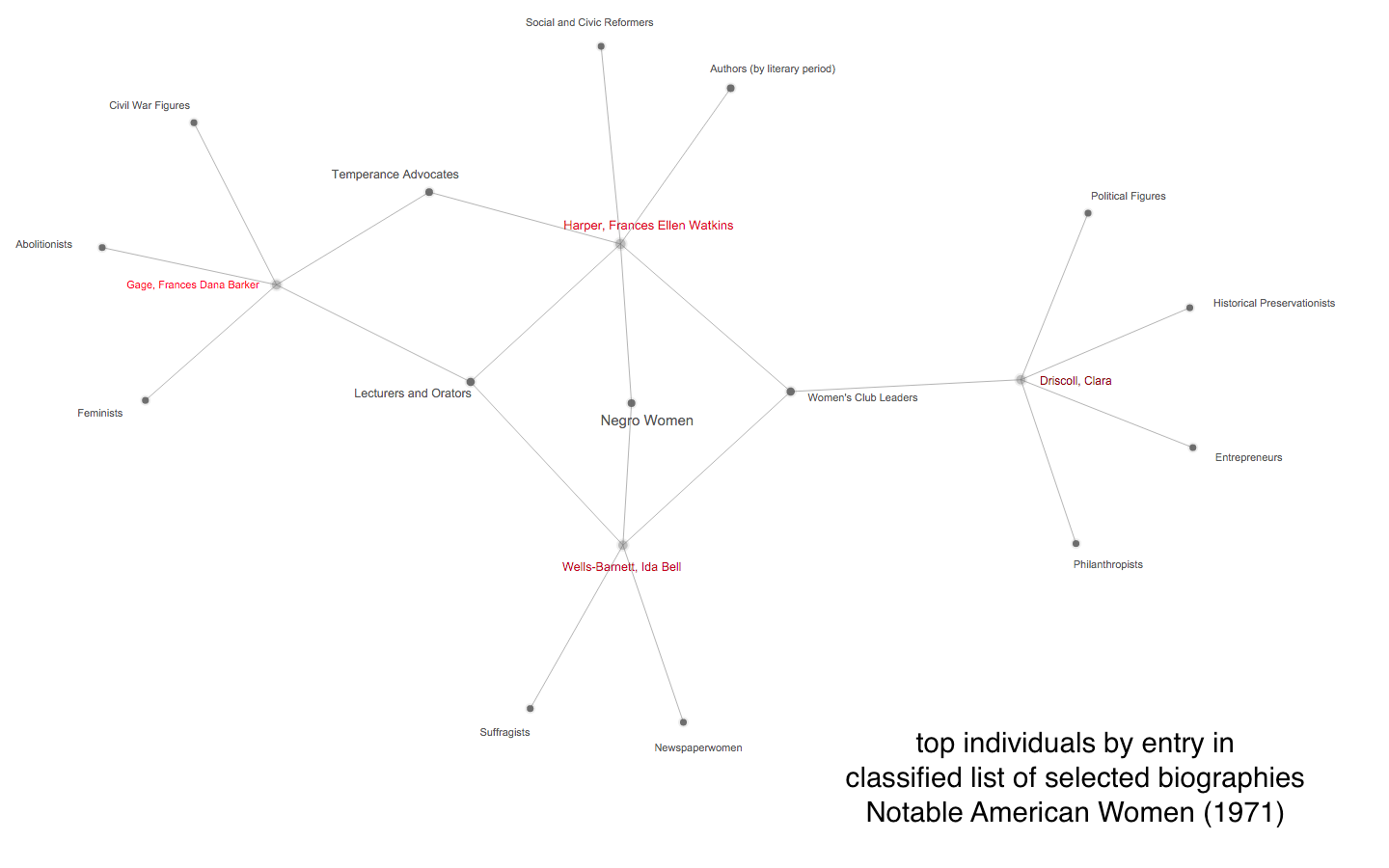

Looking at the network of “Negro Women” by their Notable American Women classified entries, I noted their centrality. Frances Harper and Ida B. Wells are the most networked women in the volumes, which is representative of their position as bridge leaders (I also noted the centrality of Frances Gage, who does not have a Wikipedia entry yet, a fate she shares with the white abolitionists Sallie Holley and Caroline Putnam).

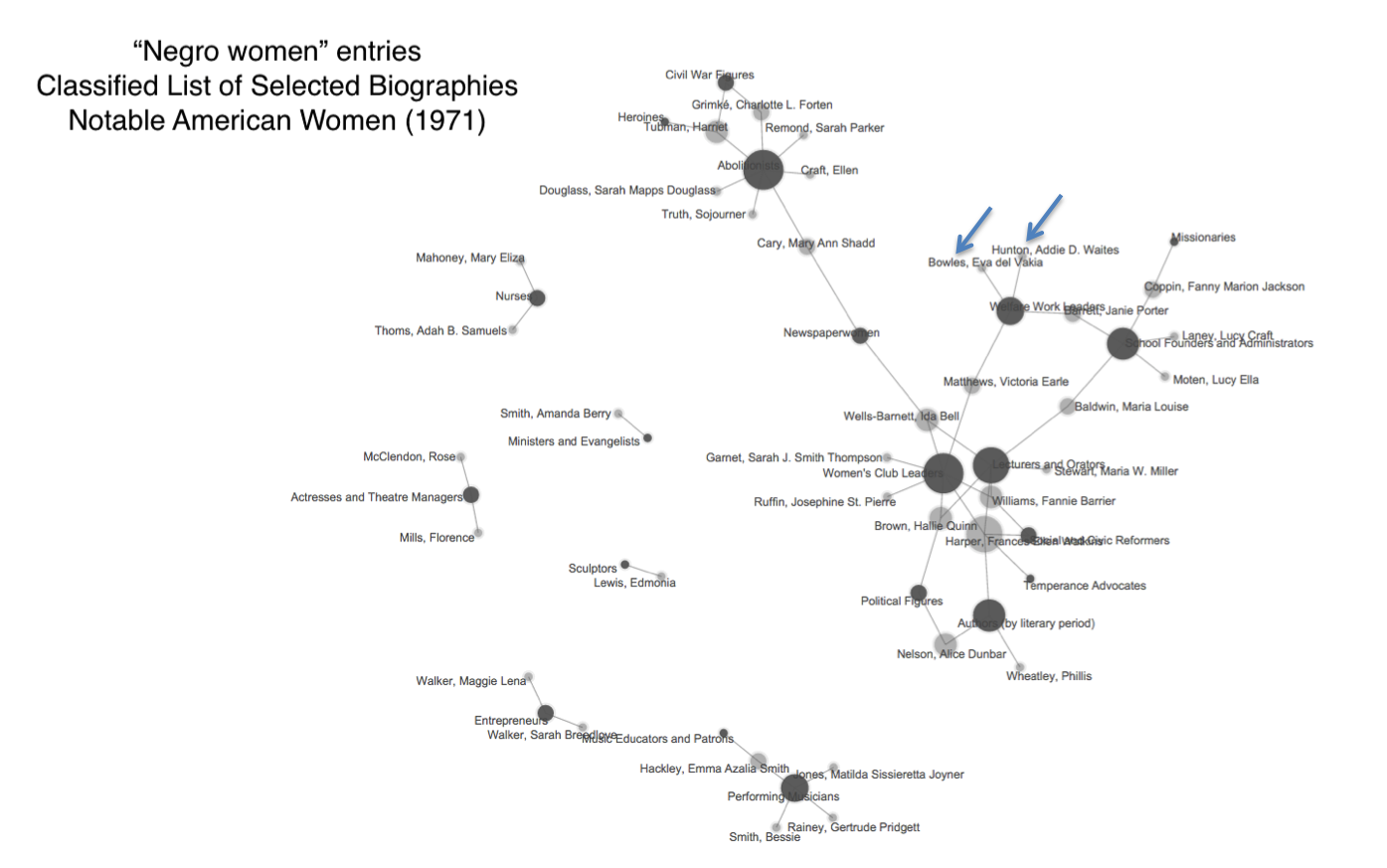

Visualizing further, I located two women who don’t have Wikipedia entries and are not included in Notable American Women:

Eva del Vakia Bowles was a long time YWCA worker who spent her life trying to improve interracial relations. She was the first black woman hired by the YWCA to head a branch. During WWI, Bowles had charge of Y’s established near war work factories to provide R & R for workers. Throughout her tenure at the Y, Bowles pressed the organization to promote black women to positions within the organization. In 1932 she resigned from her beloved Y in protest over policies she believed excluded black women from the decision making processes of the National Board.

Addie D. Waites Hunton, also a Y worker and founding member of the NAACP, was an amazing woman who along with her friend Kathryn Magnolia Johnson authored Two Colored Women with the American Expeditionary Forces (1920), which details their time as Y workers in WWI where they were among the very first black women sent. Later, she became a field worker for the NAACP, a member of the WILPF, and was an observer in Haiti in 1926 as part of that group

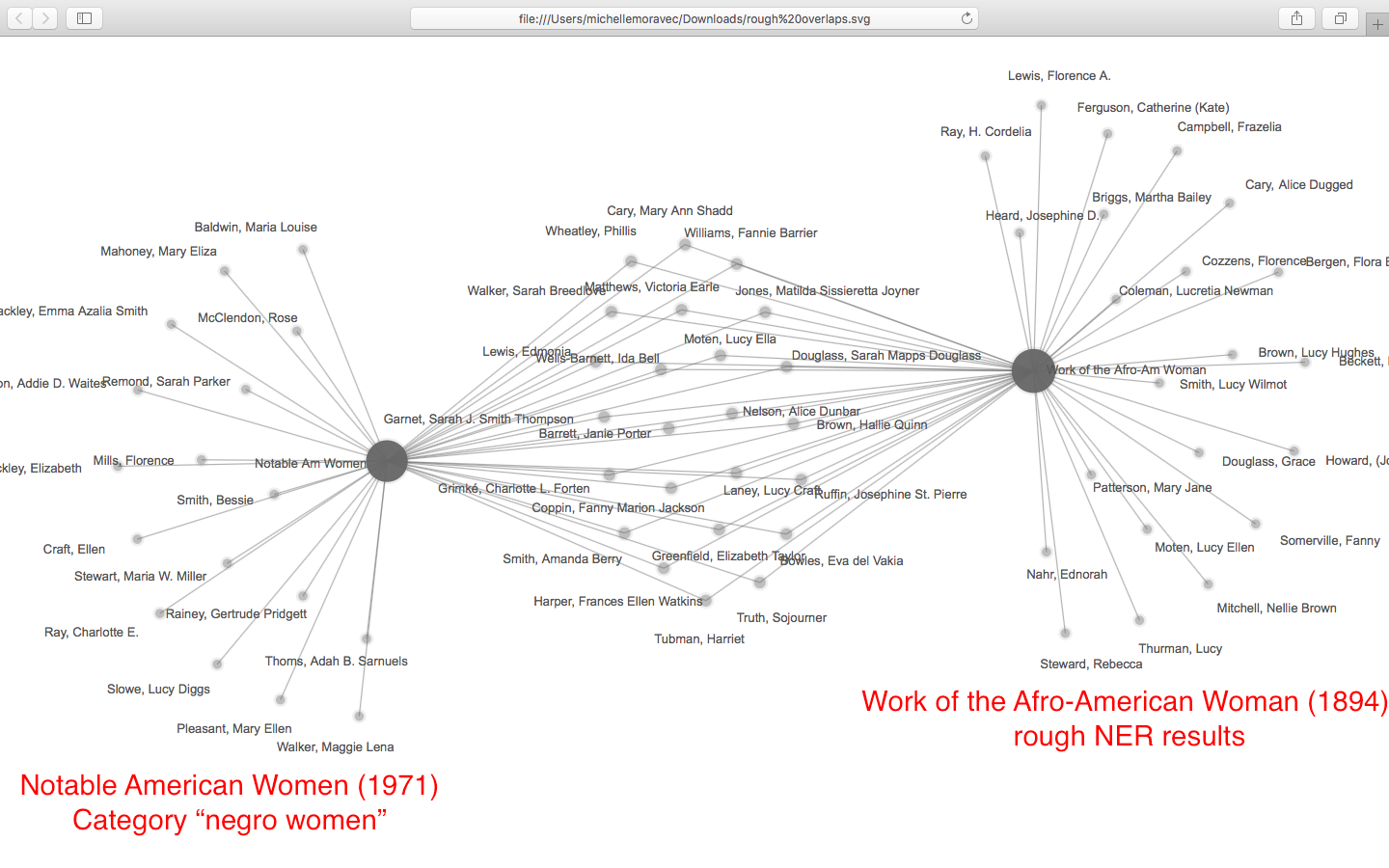

Finally, using a methodology I developed when working on the racially-biased History of Woman Suffrage, I scraped names from Mossell’s The Work of the Afro-American Woman to find women that should have appeared in Notable American Women and in Wikipedia. Although this is rough result of named extractions, it gave me a place to start.

Alice Dugged Cary does not appear in Notable American Women or Wikipedia. She was born free in 1859 became president of the State Federation of Colored Women of Georgia, librarian of first branch for African Americans in Atlanta, established first free kindergartens for African American children in Georgia, nominated as honorary member in Zeta Phi Beta and was involved in its spread.

Similarly, Lucy Ella Moten, born free in 1851, became principal of Miner Normal School, earned an M.D., and taught in the South during summer “vacations, appears in neither Notable American Women nor Wikipedia (or at least she didn’t until Mike Lyons started her page yesterday at the editathon!).

_____

Michelle Moravec (@ProfessMoravec) is Associate Professor of History at Rosemont College. She is a prominent digital historian and the digital history editor for Women and Social Movements. Her current project, The Politics of Women’s Culture, uses a combination of digital and traditional approaches to produce an intellectual history of the concept of women’s culture. She writes a monthly column for the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities, and maintains her own blog History in the City, at which an earlier version of this post first appeared.

Leave a Reply