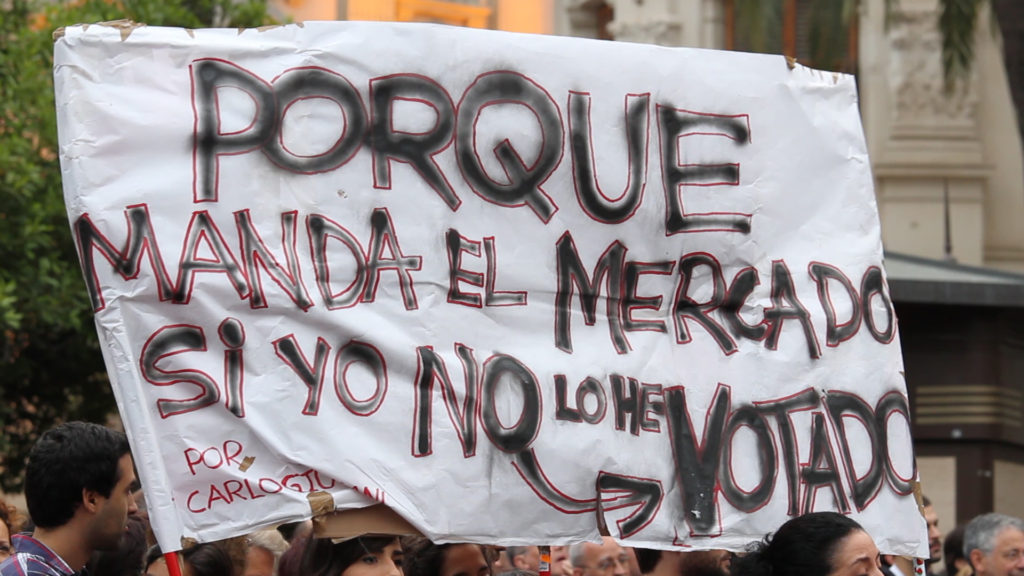

Photo courtesy of ATTAC TV

by Jorge Amar and Scott Ferguson

No private character, however pure, no personal popularity, however great, can protect from the avenging wrath of an indignant people the man who will either declare that he is in favor of fastening the gold standard upon this people, or who is willing to surrender the right of self-government and place legislative control in the hands of foreign potentates and powers.

William Jennings Bryan, “Cross of Gold,” 1896

In the wake of Syriza’s disappointing challenge to the Troika’s punishing austerity politics in the Eurozone, leftists around the globe are now turning their eyes, and hopes, to Podemos in Spain. Podemos grew out of the 15-M, or Los Indignados, anti-austerity protests back in 2011. The organization took myriad local government seats after forming an official political party in 2014. And as of the national parliamentary elections held in December 2015, Podemos has emerged as a viable third-party counterforce to Spain’s historically two-party neoliberal government. During the recent elections, the ruling, conservative People’s Party (PP) lost sixty-four seats, while the opposing Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) hemorrhaged twenty seats. Podemos, by contrast, earned sixty-nine seats, coming in just 300,000 votes behind PSOE and securing roughly 20% of the votes within the Spanish parliament. And in fourth place was Ciudadanos, the smaller, center-right “Party of the Citizenry.” Ciudadanos won a sizeable forty seats in parliament, but this was far less than early polling predicted.

Commentators have dubbed Podemos’ and Ciudadanos’ upset of Spain’s two-party system a political earthquake, while the international left is characterizing the battle ahead as source of great hope and an opportunity to bring real change to Europe. Here, however, we dampen the leftist enthusiasm surrounding the Spanish election, and regarding Podemos in particular, putting pressure on what we argue to be the party’s under-theorized and rather conservative program for economic change. Specifically, we offer a critique of Podemos’ commitment to so-called “sound finance,” as well as the tax-and-spend liberalism upon which its proposed solution to Eurozone austerity is supposed to hinge. But we also suggest a more promising way forward: that Podemos join forces with the fifth-ranking Unidad Popular party. Unidad Popular’s primary economist has turned to the heterodox school of political economy known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), coming to see what Podemos takes to be economic truths regarding the Eurozone as neoliberal myths that should be overtly politicized and rejected as such. By collaborating with Unidad Popular, we conclude, Podemos stands to not only pose a serious threat to Eurozone austerity, but also supplant the neoliberal order with an alternative and more just political-economic regime.

Political Crossroads

The general elections results that some people are characterizing as the end of the Spain’s hegemonic ’78 Regime are not quite as promising as such pronouncements let on. Podemos still lacks the necessary votes to command real power in the government, and the neoliberal bipartisanism comprised of the false choice between PP conservatives and PSOE socialists will continue to rule Spanish politics for some time. What Podemos’ electoral gains do represent is a crucial political challenge. Now it is time for Podemos to decide whether to openly collaborate with others, thereby creating a relatively stable government that can reverse austerity, or to refuse cooperation, likely forcing a new election cycle.

Though constrained in its own right, this is essentially Podemos’ decision to make. The dominant PP has no chance to win a working parliamentary majority without the endorsement of the PSOE. With an electoral base that is, demographically speaking, doomed, PP received more than 7,215,000 votes in the election, but lost more than 3,500,0000 votes from 2011. PSOE, meanwhile, saw its worst outcome since 1977: 5,530,779 votes, losing more than 1,500,000 since 2011. This leaves Podemos to negotiate between three future scenarios. None are certain. And each comes with its own rewards and pitfalls.

In the first scenario, the PP could form a government through more or less open cooperation with the PSOE and Ciudadanos. This arrangement would look something like the political makeup of the current German government. However, open collaboration may prove dangerous for the PSOE. As some regional leaders of that party are explicitly warning (if not threatening), the PSOE’s Pedro Sanchez should not rush too quickly to show support for the PP, since such an action may incite a mass defection of voters from the PSOE towards Podemos. Podemos’ recent gains have gone far to unmoor the decades-old truism that the PSOE is the Spanish left’s only feasible tool for combating PP conservatives, and the PSOE are now visibly worried.

Under a second scenario, the PSOE can attempt to constitute a new government by aligning itself with the third party, Podemos, and the fifth party, Unidad Popular. But this is also unlikely, considering the fact that Podemos rose to power by rejecting Spain’s bipartisan regime and calling for a new constitutional process. Podemos won its power from voters who resist the PP and PSOE duopoly, seeing both parties as more or less equally guilty of alienating the citizenry and exploiting the revolving doors between government, industry, and finance. Podemos disparages this class as the casta (caste) and vows to overturn it. To renege on this promise could prove politically deadly. One way to for Podemos to skirt this problem would be to demand the PSOE accept certain far-left measures, such as the referendum about Catalonia’s (and other regions’) “right to decide.” Podemos’ allies in these regions are unwavering on this issue, and persuading the PSOE to sign on to such a measure would go far to secure Podemos’ political base. Unfortunately, however, the PSOE has historically refused this policy and in all likelihood will not adopt it.

Finally, in a third scenario no coalitions are built between the reigning parties and we see a repetition of the same general elections in few months. This scenario is most likely, given the obstacles suggested above. In this case, the bipartisan regime will continue its decline and Podemos will use the PSOE’s rejection of its own faux leftism to erode more of the PSOE’s electoral base. Such a process may result in Podemos overtaking the PSOE and eventually taking command of parliament. But there are clearly many moving parts at work here, rendering the future of the Spanish left at once promising and uncertain.

Podemos’ Economic Program

Such are the political crossroads that Podemos and the Spanish left in general will face in the months ahead. But there is still another and, we would claim, more important matter to consider, and one that fundamentally shifts the ground beneath this unfolding story. This is the issue of political economy and specifically, the economic program Podemos aims to install, if and when it manages to take hold of parliament.

Surprisingly, Podemos’ economic platform has received inadequate critical attention by the leftist commentariat. This is especially true of English-language media. Much has been written about Podemos in the US, UK, and elsewhere. But such writing tends to focus on Podemos’ leader, Pablo Iglesias, and devote most of its energy to weighing the relevance of Podemos’ status as a popular political movement in relation to similar efforts around the globe. As a consequence, English speakers are offered little concrete discussion about the specific economic policies Podemos is proposing. Iglesias himself has published articles in English-language publications such as New Left Review, Jacobin, and The Guardian. These pieces explore political struggles, communication strategies, and grassroots organizing. Yet Iglesias devotes very few words to outlining Podemos’ economic program in such texts, leaving most English-language readers in the dark.

In truth, Podemos’ economic program has evolved quite a bit since the party’s initial formation. But this economic program seems to become more and more conservative as time progresses. At first, for instance, Podemos proposed a Basic Income Guarantee and debt relief for citizens, in addition to making more general promises about ending austerity. Yet month by month, Podemos has dropped both the Basic Income Guarantee and the debt relief program, as well as myriad other proposals. To be sure, the party remains committed to its central promise, which is to repair and expand Spain’s welfare state. But Podemos has conspicuously pared down its economic platform in compliance with the reigning economic orthodoxy in an effort to secure political legitimacy both within Spain and abroad.

The Trouble with Podemos

Although Podemos’s grassroots-driven rise to power should be seen as meaningful and genuinely exciting, the party’s economic strategy is simply inadequate to win the political struggle it aims to conduct against the neoliberal order. The real problem with Podemos’ political economy lies less in the specific proposals the party is offering, but rather in the unreflected neoliberal assumptions that underlie the party’s shifting economic platform. First among these assumptions is Podemos’ apparently blind commitment to the doctrine of sound finance: the mythic principle that a healthy national economy requires government to balance its budget, whether in the short run or over the course of the business cycle. As Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) has shown, this principle is not only inimical to economic productivity, but also debilitating for equality and justice. Meanwhile, this principle rests upon another noxious maxim Podemos holds dear: the false notion that states are revenue constrained and that a government must tax before it can spend toward the public good.

The only scenarios under which a sovereign government might be constrained in this way, contend MMT economists, is when international gold standards or currency-peg agreements force states to accept debt obligations in a currency over which they assert little control. Such arrangements not only limit public spending to the tax revenues the state is capable of collecting, but also force governments to bend to the dictates of international creditors. Put another way, metal standards and currency pegs transform sovereign nations into de facto colonies of other political bodies.

This is why MMT economists such as Bill Mitchell have long spoken out against the bankrupt neoliberal logics that undergird the Maastricht Treaty. Signed in February 1992 by the members of the European Community in Maastricht, Netherlands, this treaty robbed European member states of their fiscal sovereignty and established the Eurozone as a monetary union without the strong fiscal union that would be required to support it. This has resulted in an abstract and especially cruel version of an old-time gold standard, which paradoxically forgoes any basis in gold bullion. Against the warnings of a dissenting minority, the Eurozone’s quasi-gold standard has crippled European nations by restricting public spending to a finite pool of value and in turn forcing governments into brutal debt agreements.

The dominant narrative sees the resulting sovereign debt crises as the crux of the Eurozone disaster, thought to be the consequence of profligate governments being unable to live within their means. However, these crises are mere symptoms of the Eurozone’s faulty structure. The true cause of this disaster is the Eurozone’s shackling of government spending to a false finitude and treating this subjugation as a natural state of affairs. Though written in somewhat technical language, Mitchell’s account of the Eurozone’s structural failings is instructive:

It is a basic characteristic of any monetary system that government can only create risk free liabilities if they are denominated in its own currency. … [However], the current design of the Eurozone determines that the Member State governments are not sovereign in the sense that they are forced to use a foreign currency and must issue debt to private bond markets in that foreign currency to fund any fiscal deficits. … The member state governments thus can run out of money and become insolvent if the bond markets decline to purchase their debt. … Their fiscal positions must then take the full brunt of any economic downturn because there is no federal counter stabilization function. Among other things, this means the elected governments cannot guarantee the solvency of the banks that operate within their borders.i

Governments require the political capacity to create money, or “risk-free liabilities,” on demand, Mitchell explains. Such powers are needed to maintain the solvency of banks, as well as to use fiscal policy to counter recessions and depressions. The Eurozone, however, strips member states of this spending capacity and requires them to borrow on international bond markets. The result transforms sovereign governments into cash-strapped debtors, makes economic recovery for individual nation-states impossible, and dooms the entire Eurozone system to failure.

Fellow MMTers L. Randall Wray and Dimitri B. Papadimitriou describe the historical consequences of the Eurozone’s lethal design as follows:

From the very start, the European Monetary Union (EMU) was set up to fail. The host of problems we are now witnessing, from the solvency crises on the periphery to the bank runs in Spain, Greece, and Italy, were built into the very structure of the EMU and its banking system. Policymakers have admittedly responded to these various emergencies with an uninspiring mix of delaying tactics and self-destructive policy blunders, but the most fundamental mistake of all occurred well before the buildup to the current crisis. What we are witnessing are the results of a design flaw. When individual nations like Greece or Italy joined the EMU, they essentially adopted a foreign currency—the euro—but retained responsibility for their nation’s fiscal policy. This attempted separation of fiscal policy from a sovereign currency is the fatal defect that is tearing the Eurozone apart.ii

As Wray and Papadimitriou have it, the Eurozone crisis is not the direct outcome of pro-business policymaking and anti-social austerity programs, as vile as these measures are. It is, rather, an effect of the calamitous finitude baked into the EMU project. The Troika can say, “Pay up!” and “Tighten your belts!” until they are blue in the face. But European governments will be structurally incapable of settling such debts as long as their monetary sovereignty remains fettered. To make matters worse, Germany’s tendency to hold money surpluses as the Eurozone’s net exporter further exacerbates the debtor positions of other member states. If the money supply is finite in the Eurozone and the German economy hoards its export profits, this means that there is simply not enough money to go around and that import-dependent economies such as Greece, Spain, and Italy will continue to suffer deficits no matter how successfully they manage to tax their distressed populations.

Europe’s phantom gold standard has not only immiserated populations, but also quashed Syriza’s resistance to the ongoing devastation in Greece. This is not merely because the Troika rejected what Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis consistently referred to as Syriza’s “modest proposal.” It is because, unlike during previous eras when metal standards were both popularly contested and philosophically denounced, neoliberal ideology has come to wholly naturalize the Eurozone’s shrouded cross of gold. This has made real transformation unimaginable, as Varoufakis and his team sadly discovered in July 2015.

For this reason, Podemos will have to directly thematize and politicize the Eurozone’s taken-for-granted finitude if it wishes to make meaningful and lasting transformations. First and foremost, this means reclaiming the state’s monetary sovereignty and boundless fiscal capacities. But it shall also require a major propaganda campaign, aimed at persuading ordinary people that the state is limited only by real resources and productive infrastructures and simply cannot run out of an abstract unit of account. It must be made clear that only by seizing government’s power to spend as needed can Podemos hope to end austerity and create the conditions for full employment and widespread prosperity. However, for all its leftist rhetoric and broad grassroots support, Podemos remains ill-equipped to end austerity since it does not dare imagine liberating Spain’s public purse from the Troika’s asphyxiating grip.

Podemos’ economic program is thoroughly consistent with the gold standard metaphysics of sound finance. Party leaders imagine they can simultaneously adopt this ideology and succeed in accomplishing what Syriza could not: acting against austerity while playing along with Eurozone budgetary rules. Upon these faulty premises, Podemos then treats what is in reality a very conservative tax-and-spend liberalism as the crux of its economic strategy. A Podemos-led government would seek to reverse social spending cuts by increasing some taxes, creating a slate of new taxes, and reinforcing the mandate of the AEAT (the Spanish equivalent of the IRS) of fighting tax evasion. Believing that public programs should be funded by this revenue, Podemos thus plans to tether the recovery and expansion of the Spanish welfare state to the futile task of fighting tax avoidance within a zone that permits free trade and capital movement. In such a zone, every private person and corporation can shuffle money easily between countries without notice. Barring a common tax authority and total multinational cooperation, even the most vigilant efforts to collect taxes are bound to fail.

Podemos’ chief economist, Nacho Alvárez Peralta, is quite explicit about the party’s devotion to sound finance and tax-and-spend economics. Alvarez expressly supports government budget-balancing. He breaks with the European Central Bank only on the timeline he asserts is required to achieve the criteria outlined by the Eurozone’s Stability and Growth Pact (SGP). Alvarez is also the architect behind Podemos’ tax-based strategy to fix the welfare state, which he presumes to be the only way out of the current mess.

Podemos thinks it can somehow accomplish what Syriza did not. However, it must learn the true lesson of the Greek fiasco: As long as a nation-state remains inside the Eurozone and subject to its SGP budget requirements, there shall be no alternative to austerity or the neoliberal order. And with the EU Commission’s latest demand that the next Spanish government cut another 9 billion euros to meet stringent deficit targets, the stakes of learning this lesson could not be higher.

Another Future

With MMT’s critique of political economy in focus, a more promising way forward presents itself for the Spanish left, one that refuses the neoliberal premises that have come to frame Eurozone politics. As we suggested at the outset, this will require Podemos to join forces with Unidad Popular, an avowedly socialist and feminist party of the left now headed by economist and MMT advocate Alberto Garzón. As opposed to Podemos’ Iglesias and Alvarez, both Garzón and Unidad Popular’s chief economist, Eduardo Garzón (Alberto’s brother), hold a view of political economy that is very close to MMT’s understanding of monetary sovereignty, fiscal spending, and taxation. Garzón is well aware that Eurozone rules have perniciously, and needlessly, choked off the Spanish government’s spending powers, severely contracting what MMTers such as Stephanie Kelton refer to as the “fiscal space” that is necessary to sustain and enlarge a national economy.

In addition to restoring and developing the Spanish welfare state, Unidad Popular’s key economic proposal takes its cue from MMT’s idea for a federal Job Guarantee program. Garzón’s proposal is a modestly scaled version of MMT’s Job Guarantee. It is designed to provide community-focused, living-wage employment to Spain’s chronically under- and unemployed, which would not only provide immediate relief to destitute Spaniards, but also reverse the nation’s deflationary economy. Going beyond Keynesian pump priming, this Job Guarantee is meant to be a permanent public institution that expands countercyclically in lockstep with market downturns. If permitted to become a truly universal program, Spain’s Job Guarantee would serve a powerful new mediator of social production and value. In addition to setting just minimum standards for wages, working hours, and benefits, the Job Guarantee would carve out a larger space for public works that are free from market imperatives, place the program’s means of production in workers’ hands, socialize and compensate much unremunerated care work, and give everyday people a say in the shaping of their world.

What is more, Unidad Popular’s Job Guarantee scheme makes no mention of needing to meet the arbitrary budget goals of the SGP in order to fund such a program. This is because Unidad Popular roundly rejects the neoliberal premises of such goals. Indeed, if challenged by the Troika, the party is wholly prepared to set the crucial question before the body politic: Should we continue to obey the Troika’s crippling mandate in order to remain within the Eurozone? Or, shall we refuse the Troika’s dictates and risk ejection from the Eurozone? This is the question Syriza could not, or would not, ask. Yet what the Syriza tragedy has proven is that this is the key question upon which the fate of Europe shall depend.

Before the recent Spanish election, Podemos and Unidad Popular were in conversations to form a coalition. At the last minute, however, Podemos’ leaders broke off these talks for what we considered to be tactical reasons. Our hope is that there will be another chance to forge a coalition when the new elections are convoked. Of course, nothing will ensure the success of the Spanish left. All we have is our solidarity and commitment to struggle. But to fight against the neoliberal order while uncritically adopting neoliberal assumptions is to forfeit the contest from the start. Unless Podemos or any other leftist party is prepared to proffer a substantive alternative to the rules of the neoliberal game, we will no doubt suffer a disaster that is far greater than the one we are currently witnessing in Greece.

Such is the promise of MMT for the contemporary left: While MMT’s understanding of money as a limitless public instrument can free us from debt and austerity, its community-focused Job Guarantee provides means to build a new political economy, which transfigures social and ecological relations from the bottom up. Yet this is what other critical-theoretical appeals to MMT do not seem to comprehend. Reticent to appropriate and reshape the state apparatus, critics such as Nigel Dodd and David Graeber have called upon MMT’s understanding of money as a public balance sheet to challenge the inevitability of neoliberal power. In our estimation, however, MMT is more than a weapon for negating neoliberal domination. It is also a powerful tool for cultivating a positive and enduring alternative to the neoliberal catastrophe—first in Spain, then beyond.

Jorge Amar is a Spanish economist, president of the APEEP (Asociación por el Pleno Empleo y la Estabilidad de Precios, or Full Employment and Price Stability Association), and a doctoral candidate in Applied Economics at the Universidad Valencia. Recently, Amar served as economic advisor for Spain’s Unidad Popular party within the Grupo de elaboración política (Policy Elaboration Group), a provisional task force coordinated by economist Eduardo Garzón.

Scott Ferguson holds a Ph.D. in Rhetoric and Film Studies from the University of California, Berkeley and is currently an assistant professor of Humanities & Cultural Studies at the University of South Florida. He is also a Research Scholar at the Binzagr Institute for Sustainable Prosperity. His essays have appeared in CounterPunch, Screen, Arcade, the Critical Inquiry blog, Naked Capitalism, Qui Parle, and Liminalities.

References

Álvarez Peralta, Nacho. 2015. “Recuperar el Estado de bienestar.” El País, December 15. http://elpais.com/elpais/2015/12/15/opinion/1450206651_989640.html

Beas, Diego. 2011. “How Spain’s 15-M Movement is Redefining Politics.” Guardian, October 15. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/oct/15/spain-15-m-movement-activism.

Cañil, Ana R. 2015. “Alberta Rivera, el príncipe azul del Ibex 35.” El Diario, July 3. http://www.eldiario.es/zonacritica/Causas-meteorico-despegue-Albert-Rivera_6_363673650.html.

Carlin, John. 2015. “Los caballeros de la Mesa Redonda.” El País, January 27. http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2015/01/27/actualidad/1422384264_753104.html.

Castro, Irene. 2015. “Pedro Sánchez pacta con sus barones las líneas rojas de un acuerdo con Podemos.” El Diario, December 27. http://www.eldiario.es/politica/Pedro-Sanchez-barones-acuerdo-Podemos_0_467203568.html.

Council of the European Communities. 1992. “Treaty on European Union.” Commission of the European Communities. http://europa.eu/eu-law/decision-making/treaties/pdf/treaty_on_european_union/treaty_on_european_union_en.pdf.

El Diario. 2015. “Mariano Rajoy pide una gran coalición y no descarta ofrecer ministerios a PSOE y Ciudadanos.” El Diario, December 29. http://www.eldiario.es/politica/Mariano-Rajoy-PSOE-Ciudadanos-Gobierno_0_467903488.html.

Dodd, Nigel. 2014. The Social Life of Money. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Errejón, José. 2013. “La crisis del régimen del 78.” Viento Sur, July 1. http://www.vientosur.info/spip.php?article7571.

Europa Press. 2015. “Podemos no permitirá un gobierno del PP pero condiciona su apoyo al PSOE al derecho a decidir.” El Economista, December 21. http://ecodiario.eleconomista.es/politica/noticias/7237104/12/15/20D-Podemos-no-permitira-un-gobierno-del-PP-pero-condiciona-su-apoyo-al-PSOE-al-derecho-a-decidir.html.

Ferguson, Scott. 2015. “Universal Basic Income: A Laissez-Faire Future?” CounterPunch, November 13. http://www.counterpunch.org/2015/11/13/universal-basic-income-a-laissez-faire-future/.

Garzón, Alberto. 2015. “The Problem with Podemos.” Jacobin, March 13. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/03/podemos-pablo-iglesias-izquierda-unida/.

Eduardo Garzón’s Twitter page. 2016. https://twitter.com/edugaresp (accessed April 19, 2016).

Godley, Wynne. 1992. “Maastricht and All That.” London Review of Books 14, no. 19: 3-4. http://www.lrb.co.uk/v14/n19/wynne-godley/maastricht-and-all-.

González, Bernardo Gutiérrez. 2016. “The ‘Podemos Wave’ as a Global Hope.” Open Democracy, December 20. http://www.opendemocracy.net/democraciaabierta/bernardo-guti-rrez-gonz-lez/podemos-wave-as-global-hope.

Graeber, David. 2011. Debt: The First 5,000 Years. New York: Melville House Press.

Iglesias, Pablo. 2015. “Politics Isn’t a Fairytale About Good Versus Bad.” The Guardian, December 21. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/dec/21/politics-isnt-fairytale-good-versus-bad.

Iglesias, Pablo. 2015. “The Spanish Response.” Jacobin, December 19. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/12/pablo-iglesias-interview-jacobin-podemos-spain-austerity/.

Iglesias, Pablo. 2015. “Understanding Podemos.” New Left Review 93: 7–22. http://www.newleftreview.org/II/93/pablo-iglesias-understanding-podemos.

Stephanie Kelton’s personal website. 2016. http://stephaniekelton.com/ (accessed April 19, 2016).

Lasa, Victor. 2015. “The New Spain: Between Uncertainty and Hope.” CounterPunch, December 22. http://www.counterpunch.org/2015/12/22/the-new-spain-between-uncertainty-and-hope/.

Lerner, Abba P. 1943. “Functional Finance and the Federal Debt.” Social Research 10, no. 1: 38-51. http://k.web.umkc.edu/keltons/Papers/501/functional%20finance.pdf.

Mecpoc’s YouTube channel. 2010. “Keynes Celebrates the End of the Gold Standard.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U1S9F3agsUA.

Mendizabal, A. R. 2015. “Pablo Iglesias tranquiliza a Wall Street: ‘No hay alternativa a la economía de mercado.’” Capital Madrid, June 20. https://www.capitalmadrid.com/2015/6/20/38568/pablo-iglesias-tranquiliza-a-wall-street-no-hay-alternativa-a-la-economia-de-mercado.html.

Mitchell, Bill. 2012. “Budget Surpluses Are Not National Saving – Redux.” Bill Mitchell: Billy Blog, August 7. http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=20536.

Mitchell, Bill. 2016. “Democracy in Europe requires Eurozone Breakup,” Billy Blog, January 6. http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=32730.

Mitchell, Bill. 2015. “Demystifying Modern Monetary Theory.” Institute for New Economic Thinking, March 19. http://ineteconomics.org/ideas-papers/interviews-talks/demystifying-modern-monetary-theory.

Mitchell, Bill. 2013. “Options for Europe: Part 1.” Bill Mitchell: Billy Blog, December 31. http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=26667.

Moreno, Felix. 2014. “50% Youth Unemployment in Spain Fuels Radicalization of Protests.” RT, March 24. https://www.rt.com/op-edge/radicalization-of-protests-in-spain-809/.

Myerson, Jesse A. 2015. “Monetarily, We Are Already In The Next System…” The Next System Project, October 8. http://thenextsystem.org/monetarily-we-are-already-in-the-next-system-we-just-dont-act-like-it/

Nelson, Fraser. 2015. “Political Earthquake in Spain as Podemos Takes 20pc of Vote.” The Spectator, December 20. http://blogs.spectator.co.uk/2015/12/political-earthquake-in-spain-as-exit-poll-shows-podemos-surging-to-22pc/.

Parguez, Alain. 1999. “The Expected Failure of the European Economic and Monetary Union: A False Money Against the Real Economy.” Eastern Economic Journal 25, no. 1: 63-76. http://college.holycross.edu/eej/Volume25/V25N1P63_76.pdf.

Pargeuz, Alain. 2011. “Guest Post: A Fresh Proposal for Escaping the Euro Crisis.” Yanis Varoufakis: Thoughts for the Post-2008 World. http://yanisvaroufakis.eu/2011/11/25/a-fresh-proposal-for-escaping-the-euro-crisis-guest-post-by-alain-parguez/.

Pérez, Claudi. 2015. “Bruselas señala que el nuevo Gobierno deberá recortar casi 9.000 millones.” El País, November 5. http://economia.elpais.com/economia/2015/11/05/actualidad/1446714490_704857.html.

Pierce, Dale. 2013. “What is Modern Monetary Theory, or ‘MMT’?” New Economic Perspectives, March 11. http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2013/03/what-is-modern-monetary-theory-or-mmt.html.

Rojer, Rebecca. 2014. “The Job Guarantee.” Jacobin, January 10. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2014/01/the-job-guarantee-video/.

Rojer, Rebecca. 2014. “The World According to Modern Monetary Theory.” The New Inquiry, April 11. http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/the-world-according-to-modern-monetary-theory/.

Rucinski, Tracy, and Finoa Ortiz. 2011. “Spain Protests Rock Nation, Tens of Thousands Fill the Cities Over Joblessness.” The World Post, May 21. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/05/21/spain-protests-joblessness_n_865058.html.

Sánchez, Raúl. 2015. “La brecha generacional sostiene gran parte de los resultados electorales del PP.” El Diario, December 24. http://www.eldiario.es/politica/generacional-mantiene-resultados-electorales-PP_0_465803541.html.

Tortosa, María Dolores. 2015. “Susana Díaz se opone tanto a un pacto con el PP como con Podemos.” Ideal, December 22. http://www.ideal.es/andalucia/201512/22/susana-diaz-opone-tanto-20151222005459-v.html.

Unidad Popular’s homepage. http://www.unidadpopular.es/ (accessed March 24, 2016).

University of Groningen. 2012. “William Jennings Bryan Cross of Gold Speech July 8, 1896.” American History: From Revolution to Reconstruction and Beyond. http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/documents/1876-1900/william-jennings-bryan-cross-of-gold-speech-july-8-1896.php.

Varoufakis, Yanis. 2015. “Greece, Germany and the Eurozone.” Paper presented at the Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, Berlin, June 8. https://yanisvaroufakis.eu/2015/06/09/greeces-future-in-the-eurozone-keynote-at-the-hans-bockler-stiftung-berlin-8th-june-2015/.

Varoufakis, Yanis. 2013. “Modest Proposal. Yanis Varoufakis: Thoughts for the Post-2008 World. https://yanisvaroufakis.eu/euro-crisis/modest-proposal/.

Wikipedia. 2016. “Greenback Party.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_troika (accessed April 19, 2016)

Wikipedia. 2015. “European Troika.” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_troika (accessed March 20, 2016).

Wray, Randall L., and Dimitri B. Papadimitriou. 2012. “Euroland’s Original Sin.” Levy Economics Institute of Bard College Policy Note 8: 1-5. http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/pn_12_08.pdf.

Wray, L. Randall. 2014. “Modern Money Theory: The Basics.” New Economic Perspectives, June 24. http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2014/06/modern-money-theory-basics.html.

Wray, L. Randall. 2014. “What Are Taxes For? The MMT Approach.” New Economic Perspectives, May 15. http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2014/05/taxes-mmt-approach.html.

i. Bill Mitchell, “Democracy in Europe requires Eurozone Breakup,” Billy Blog (blog), January 6, 2016, http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=32730.

ii. Randall L. Wray and Dimitri B. Papadimitriou, “Euroland’s Original Sin,” Policy Note 8, July 2012, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/pn_12_08.pdf.