by Charles Bernstein

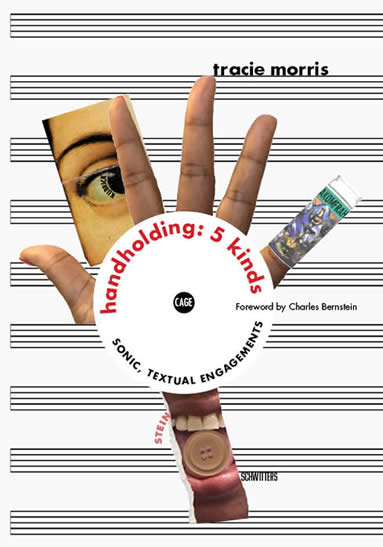

boundary 2 is proud to present Charles Bernstein’s foreword to Tracie Morris’s new book, Handholding 5 Ways (New York: Kore Press, 2016).

For the last two decades, Tracie Morris has been transfiguring the relation of text to performance and word to sound. Such iconic Morris works as “Slave Sho to Video aka Black but Beautiful” and “Chain Gang” are scoreless sound poems, originating in improvised live performance. At the same time, Morris has published text-based work in Intermission (1998) and Rhyme Scheme (2012). Hand-Holding is the first collection of Morris’s work to present a full spectrum of her approaches to poetry. This is not so much a collection of poems, as conventionally understood, as a display of the possibilities for poetry. Each work here is not just in a different style or form but rather explores different aspects poetry as a medium: re-sounding, re-vising, resonating, re-calling, re-performing, re-imaginings. In Hand-Holding the medium is messaged so that troglodyte binaries like politics and aesthetics, original and translation, and oral and written go the way of Plato’s cave by way of Niagara Falls.

In her first recordings, Morris was already crossing the Rubicon between spoken word and sound poetry, showing that the river was only skin deep. In one of the two revisionist versions of a major modernist poem in this collection, Morris returns to the magnum opus of modernist sound poetry, Kurt Schwitters’s “Ursonate” (1922-1932). For “Resonatae” Morris does not perform Schwitters’s score; rather, she collaborates with the signal recording of the work by Schwitters’s son Ernst. You don’t hear Ernst’s recording in Morris’s work, but she is taking her cue from this performance. Because Morris has dispensed with the written (alphabetic) score, she is able to improvise, loop, extend, and re-perform “Ursonate” in a way that sets her performance apart. Her tempo is at half the pace of Christian Bök’s magnificent, athletic version, which has become a classic of the sound poetry repertory. “Resonatae” re-spatializes the pitch of “Ursonate” as she re-forms its rhythms, creating a meditative, interior space that makes a resonant contrast to Bök; indeed to fully understand the achievement of Morris and Bök, you need to listen to both.[1] While Bök’s performance creates a concave acoustic space, Morris creates a convex one. This becomes especially poignant midway in the performance, when rather than create a percussive rhythm with phonemes popping against one another, Morris practically lapses into speech, into talking, into direct address. “Resonatae” is a brilliant charm, deepening and extending this modernist classic in a way comparable to Glenn Gould’s revisionist Bach.

Listen to the first minute of “Resonate” (the full recording is 41 minutes).

“Eyes Wide Shut” is another thing entirely. This poem invents a new medium for poetry, based on recent adaption by some American poets of Japanese “benshi” (live narration for silent films). “Eyes Wide Shut” provides a new commentary track for the Stanley Kubrick movie: the audio file synchs with the full movie, while the printed poem is a sort of paratext or microfiche version. The two versions of the work are incommensurable; or maybe the relation is like a song lyric to a song. Listening to the audio track alone, the experience is of long silences, with voice suddenly breaking into the silence.

“Songs and Other Sevens,” like “Eyes Wide Shut,” is a commentary on a movie, John Akomfrah’s1993 documentary, Seven Songs for Malcolm X. Morris again provides two discrepant versions: one on the page, one as a sound recording. In this case, the audio is not meant to accompany the film but to provide a shadow version of the text (or perhaps it is the other way around and the text is the ghost of the audio). Listening to the audio track, the silences stand out as much as the sound in a way that undercuts the rhetorical momentum associated with poetry performance. Morris makes the space between the lines palpable. The neutrality of voice brings to mind the French poet Claude Royet-Journoud’s desire for a lack of acoustic resonance in a reading (Royet-Journoud employs a timer to insert non-rhythmic silences between cut-up phrases). With this frame established, the alphabetic poem seems non-linear: you can read it backward or move around in it, sample it.

All that silence is made explicit by “5’05,” Morris transcription/transposition of the John Cage classic “4’33,” where Cage frames a silence that is filled with ambient sound as well as with the sound of listening. Morris records sound as space: rooms, which like stanzas, can be a place to breath or an enclosure that closes you off from the world.

“If I Reviewed Her,” Morris’s reworking of Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons (1914) is a textual tour-de-force and the perfect bookend to her Schwitters: two towering modernist classics startlingly transformed. Stein: thou art translated! There is some connection to Harryette Mullens’s Trimmings or perhaps to say that Trimmings is a touchstone for what is done in “If I Reviewed Her,” Morris affords much cultural surround to her Stein variations and impromptus: Shakespeare and Williams, Yiddish and Broadway. She gives Stein back her accents, entering into a dialog with a work that veers toward soliloquy. Crucially, Morris re-sutures Stein’s relation to blackness, which Stein was unable, given her time, to come to terms with: “What she said here is unfortunate. It isn’t fortune and it isn’t innate. I’ll leave it there but it was a disappointment. I’ll say that. (She won’t.) A ‘white old chat churner’ after all.”

Listen to the first minute of “If I Reviewed Her” (the full recording is 1 hour and 44 minutes).

In “If I Reviewed Her” Morris asks the two central questions for Handholding: “What’s a room?” and “What’s an heirloom?”

She doesn’t show, she tells.

Charles Bernstein

June 10, 2015

Carroll Gardens

[1] Listen to Bök’s superb performance, along with Ernst Schwitters’s hauntingly beautiful one, at PennSound.

Of Related Interest

boundary 2’s 2015 “Dossier on Race and Writing,” ed. Dawn Lundy Martin

Tracie Morris, “Rakim’s Performativity” from boundary 2 (2009)

Leave a Reply