by Nathan K. Hensley

The book I’ve chosen to describe for this brief position paper is not a book at all, really, but a book in the process of becoming: call it an essay, as in a trial or experiment. It’s one of Swinburne’s notebooks from his undergraduate years at Oxford. Some of this writing would later be “upcycled” into Poems and Ballads, of 1866 (that’s Antoinette and Isabel’s great term, from Ten Books), and in Figure 2 you can see the first, respectable edition of that infamous book, put out by Richard Moxon, alongside the second, pornographic one, issued after the indecency charges, published by John Camden Hotten.

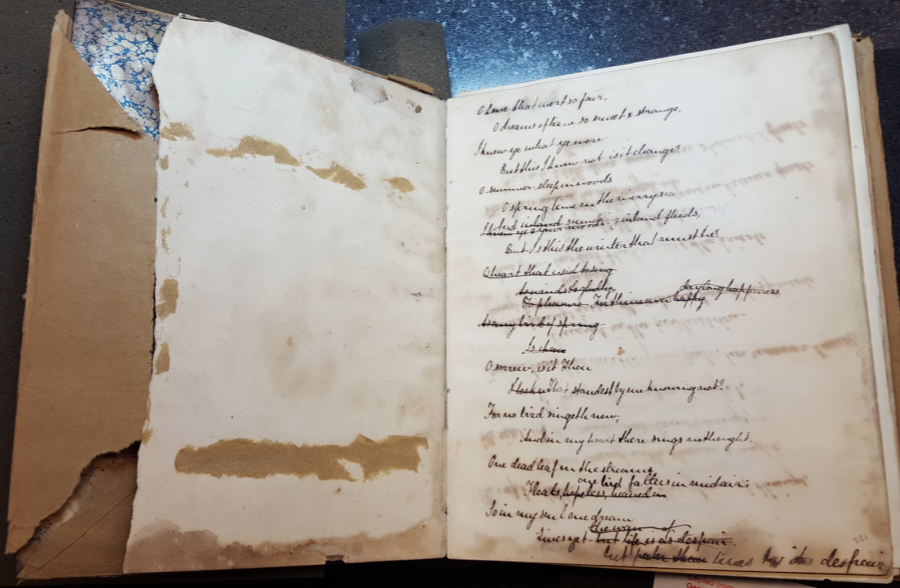

As is true of all books, the composition, compilation, and publication of Poems and Ballads left in its wake a jumbled collection of cancelled versions, outtakes, and half-formed trials: a train of loose material and juvenilia, spread now across archives in England and the US, some of it miraculously living at my own university, that would never be crystallized into any final public form at all.

The non-book depicted above is one such record of abandoned energy or thought-in-motion, a testament, I mean, to writing as a process and not a thing. Orphaned in an archive in Washington, DC, it would have been incapable of “shaping empire” in models of analysis that borrow from Foucault or Althusser or just the intellectual conventions of our field to assess how a text might (in the words of Ten Books) “influence … imperial discourse and power” (Burton and Hofmeyr 2014: 3).

In my work I’ve tried to pivot away from terms like discourse, influence, and power, and toward another set of conceptual levers — literary form and sovereign violence — to ask how nineteenth century thinkers used literary presentation to conceive their modernity’s uncanny coincidence with brute force. Part of this means expanding what it might mean for a book to be “about” empire, and could (I hope) help shift us away from the usual suspects of our “literature and empire” syllabi and toward the era’s anatomies of harm, catastrophe, and human waste: so Wuthering Heights, The Mill on the Floss, and Our Mutual Friend provisionally in place of Kipling and Conan Doyle. It also might push us to look for conceptual productivity rather than ideological inscription. The question becomes not how common sense circulates, discourses accrue, or ideologies stick, but how literary texts work to imagine the new.

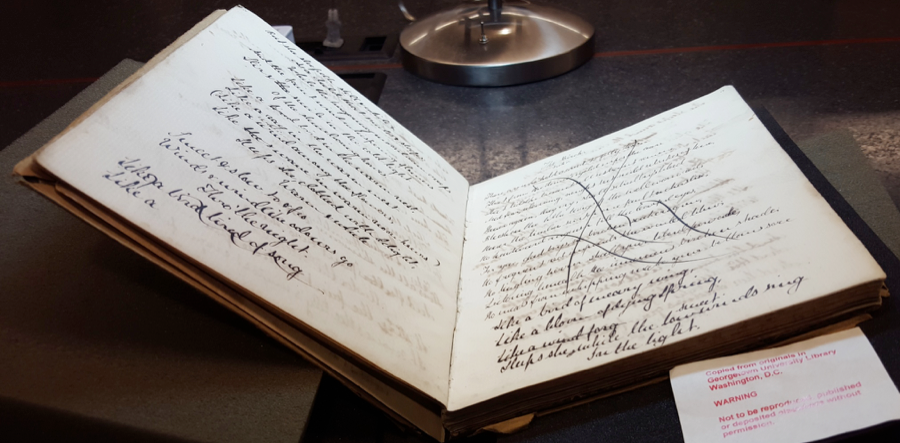

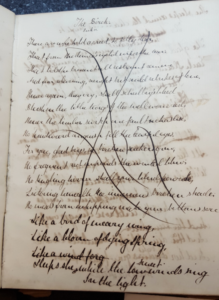

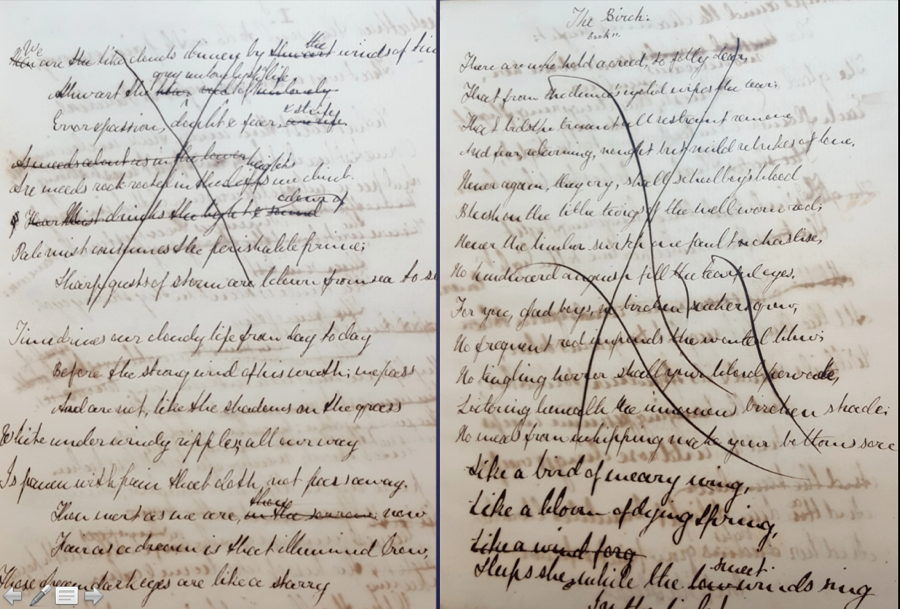

Of course, one provocation of Ten Books that Shaped the British Empire is to ask whether books shape empire at all, and to answer that we would need to know what a “book” is and what “shaping” means — and the authors address these questions– but also what constitutes “the British empire.” What do we talk about when we talk about empire? The question is more difficult than it sounds, and I think Swinburne can help. What you see below is the first page of a never-published poem in the Oxford notebook called “The Birch.”

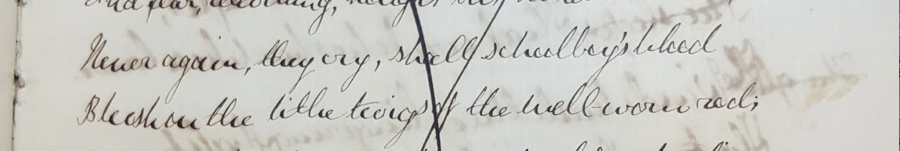

In it, Swinburne lovingly describes the pleasures of being beaten with a wooden rod. He lingers on the opened flesh, the dripping fluids, the sublime pleasures of all this. Like other of Swinburne’s Sadean flogging poems –dismissed as subliterary by Steven Marcus but expertly read by Yopie Prins– “The Birch” is a poem in praise of being beaten, and in this it well evinces what Ellis Hanson elsewhere in this series of blog posts refers to as “kink.” It is also, as Prins (2013) notes of other Swinburnean flogging poems, a poem about what poetry is and does, and is therefore, I’ll say, a poem not just about desire or violence but about form itself.

There’s no space for a real reading in this short and telegraphic blog post, but trust me that Swinburne’s speaker mocks the right-minded people who would deny the delights of what the poem with jarring fondness calls “chastise[ment].”

Taking this fondness for vexation yet further is my favorite poem and ballad in the published collection of that name, “Anactoria.” That poem places at the literal, mathematical center of its long catalogue of physical vexations what its speaker refers to as “the mystery of the cruelty of things”: the phrase comes from lines 152-154 of the 304 line poem. And like “Anactoria,” “The Birch” puts harm at the very core of its system: physical violence is the dark star around which orbit all its other affects, pleasure included. Swinburne’s early verse, I’m saying, anatomizes violence and understands somatic injury as its conceptual degree zero.

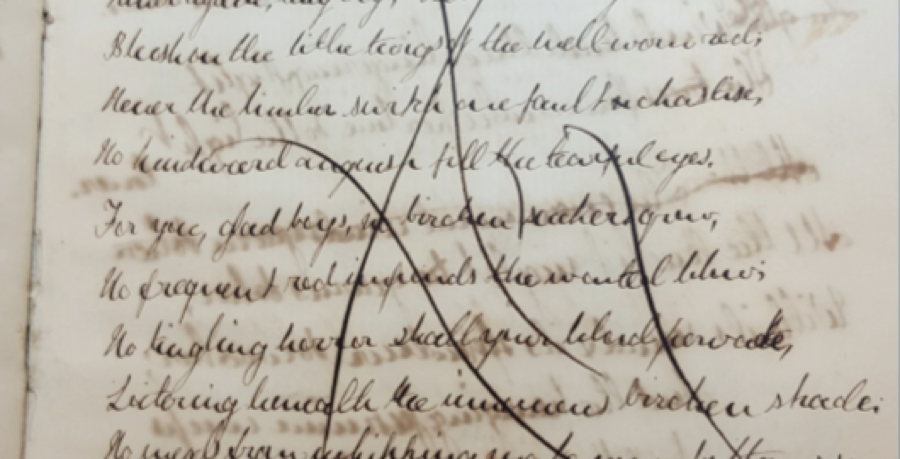

But like the other Poems and Ballads composed in this period, “The Birch” unfolds within a fantastically rigorous formal structure. Elsewhere it’s roundels and Old French verse forms; here it’s end-stopped couplets, a grid of masculine rhymes and mostly iambs that is slashed over with flaying strokes from Swinburne’s fountain pen. These marks lacerate the tight form of the poetry they overwrite but do not cancel.

In lavish, six inch strokes, Swinburne inscribes onto the manuscript of “The Birch” a tension between extravagant harm and regulative form: a co-traveling of rage and order that this manuscript presentation does not –need not– resolve. Crucially for my sense of this as an act of materialized political thinking, physical violence is here uncannily bound up with the very regulative ensemble it seems to contravene. The physical capacities of this manuscript enable that suspension.

Since this is a short post and I discuss these questions at more length in a forthcoming book, I’ll end listwise, with three things that make this object useful to me as a kind of tactical metonymy, the crown for the king, in this conversation about critical engagements with empire now:

(1) It is singular; no other object on earth is identical with it, and as I’ve only just been able to hint at here, it is not identical with itself either.

(2) It is — and this should be obvious– material. It is a physical object whose physicality is part of its apparatus for making meaning. As this suggests this object is also highly conscious of itself as form; its effects depend on what George Saintsbury (with Swinburne as an example) understood as “the laws of meter” (1910: 25): I mean the restraining or (in the Kantian sense) regulative functions of form that Swinburne here luxuriously overcodes.

Finally (3), it is thought. Swinburne is not writing about India, not describing trade routes or troop movements or the suppressions of rebellions. He is instead writing about violence: and the point is that for an empire that routed its self understanding through the concept of law, this effort to think obscene violence and regulative form together makes “The Birch” political theory for the age of liberal empire.

In its pitiless, I will say diagnostic analysis of how legality and harm travel together, and in its marshaling of poetic form to enact this cotraveling, Swinburne’s notebook pushes us away from vestigially empiricist models of influence and toward an understanding of how literary presentation can enact thought. But this object also does something more, which is to help us know empire as what it is: the targeted application of physical violence against certain bodies for the benefit of others — the mystery of the cruelty of things. As belated readers of documents like this, our tasks might be, first, to show how the Victorian thinkers we love mediate this obscene mystery into form, and second, if we can stomach it, to use those encounters as a way to begin reconceiving the present.

References

Burton, Antoinette, and Isobel Hofmeyr, eds. 2014. Ten Books that Shaped the British Empire: Creating an Imperial Commons. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Marcus, Steven. 1975. The Other Victorians: A Study of Sexuality and Pornography in Mid-Nineteenth Century England. New York: Basic Books.

Prins, Yopie. 2013. “Metrical Discipline: Algernon Swinburne on ‘The Flogging Block.’” In Algernon Charles Swinburne: Unofficial Laureate, edited by Catherine Maxwell and Stefano Evangelista. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Saintsbury, George. 1910. A History of English Prosody: Volume III, From Blake to Mr. Swinburne. London: Macmillan & Co.

Swinburne, Algernon Charles. 1859[?] Oxford Notebook. Manuscript notebook, Booth Family Center for Special Collections, Georgetown University.

—. 1866. Poems and Ballads. London: Edward Moxon.

—. 1866. Poems and Ballads. London: John Camden Hotten.

CONTRIBUTOR’S NOTE

Nathan K. Hensley is assistant professor of English at Georgetown University. He is the author of Forms of Empire: The Poetics of Victorian Sovereignty (2016).

Leave a Reply