by David Thomas

The West welcomed East Germany to the end-of-history by flying in David Hasselhoff for Berlin’s New Year celebrations. From the top of the fallen wall, clad in a pulsing light-spangled jacket, Hasselhoff regaled half a million people with the period’s unofficial anthem, “Looking for Freedom.” It is still, to date, one of Germany’s bestselling songs.

Two years earlier, as Margaret Thatcher closed in on her second re-election, Hot Chocolate’s former front man, Errol Brown, had also lent his weight to the liberal cause. During the 1987 Conservative Party Conference, the disco hitmaker stepped up to the podium and led the entire caucus in a rousing rendition of John Lennon’s pop-socialist anthem “Imagine” (Wilson 2013: 41):

Imagine no possessions

I wonder if you can

No need for greed or hunger

A brotherhood of man

Imagine all the people

Sharing all the world

You, you may say I’m a dreamer,

But I’m not the only one

I hope some day you’ll join us

And the world will live as one

Little wonder that irony was the order of the day. Confident in their unassailable position, and wryly indulgent of the counterculture’s crabby idealism, the architects of globalization rested content on their laurels. There was much to celebrate. Liberal democracy had vaulted over the last great hurdle on its pathway to perpetual peace. Francis Fukuyama captured the mood as he sketched out the lineaments of his wildly popular end-of-history thesis:

What we may be witnessing in not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of post-war history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government. (Fukuyama 1989: 4)

The course of world events allowed Fukuyama to stand by this claim for almost thirty years. Writing in 2007, on the very cusp of the 2008 financial crisis, he offered a confident and largely unqualified reassertion of his fundamental argument:

I believe that the European Union more accurately reflects what the world will look like at the end of history than the contemporary United States. The EU’s attempt to transcend sovereignty and traditional power politics by establishing a transnational rule of law is much more in line with a ‘post-historical’ world than the Americans’ continuing belief in God, national sovereignty, and their military. (Fukuyama 2007)

Yet ten years on – as Fukuyama himself has conceded – the same claim has begun to leave behind a bad taste in the mouth. Walls are in vogue again. And as a fragile European Union teeters on the brink of fragmentation, the new political trajectory of the United States seems the more reliable harbinger of the political futures that await us, futures overshadowed by a resurgence of rightwing authoritarianism and a reactive cascade of unpredictable international statecraft. Indeed, as Trump has ridden a wave of anti-establishment discontent into the White House, “Americans’ continuing belief in God, national sovereignty, and their military” now looms large over the old effort to “transcend sovereignty and traditional power politics by establishing a transnational rule of law.”

Even prior to Brexit and Trump’s election, the new tenor of the times was starting to emerge. As armed guards rolled out the checkpoints and the razor wire, as miles of ad hoc barrier unwound across Europe, it became apparent that the open borders of globalization belonged to another era. The Schengen Agreement was a thing of the past, a bitterly regretted utopian folly. And as the specter of Trump’s “great, great wall” hovered at the outer edge of possibility, it was becoming clearer that other dreams were dying too: You could keep your hungry, your poor, your tired, there was no room for them here.

The truth was, however, these high-walled fever dreams had been under construction for some time. The work had never really stopped. Long before the “great wall” was rumored, and even as the old Iron Curtain came crashing down, the world’s wealthy had peered out from behind their battlements in the sky. This is Mike Davis writing in the mid-1980s:

According to its advance publicity, Trump Castle will be a medievalized Bonaventure, with six coned and crenellated cylinders, plated in gold leaf, and surrounded by a real moat with drawbridges. These current designs for fortified skyscrapers indicate a vogue for battlements not seen since the great armoury boom that followed the Labour Rebellion of 1877. In so doing, they also signal the coercive intent of postmodernist architecture in its ambition, not to hegemonize the city in the fashion of the great modernist buildings, but rather to polarize it into radically antagonistic spaces. (Davis 1985: 112-3)

When Davis wrote, he would probably have been surprised to learn that the proposed owner-occupant of this “medievalised Bonaventure” would one day descend in his golden elevator to lead a populist insurgency against “out-of-touch elites.” He would probably have been less surprised to hear that when he came, he came promising the Rust Belt’s dispossessed fortifications and battlements of their own.

To understand the success of the strategy, and to understand the strange mismatch of class interests that defines the Trump mandate, one has to dig beneath the concrete partitions of the “postmodern” city and search within the rusting husk of the American factory system to grasp the hidden economic imperatives and political contingencies that produced deindustrialization and financialization as coeval phenomenon. Here – as many of us are belatedly beginning to realize – Robert Brenner’s history of postwar economic development proves an indispensable resource.

Much of Brenner’s later work has focused on the turbulent transition from the global economy’s belle époque – the period of unprecedented economic dynamism the lasted from the close of the war to the early 1970s – to the “long downturn” that has followed in its wake. His work has drawn attention to a progressive reallocation of capital investments away from industrial manufacturing and into the so-called FIRE (Finance, Insurance and Real Estate) sector. In Brenner’s account of the history, as emerging industrial economies began contesting American manufacturing market dominance struggle for market share reached such a pitch of intensity that companies became accustomed to operating with radically reduced profit margins.

In response to a corresponding decline in rates of return, investors became shyer of the manufacturing sector and sought to diversify their portfolios. And as fallow capital sought new routes to profit the structural import of the FIRE sector intensified. From the late 1970s through to the first decade of the new millennium the finance industry’s signature methods and investment strategies became more and more computationally sophisticated and systemically pervasive. Among the symptoms of the FIRE sector’s new significance was the rapid reconstitution of urban space that Davis describes. And it was, of course, in the context of the FIRE sector’s expansion that Trump emerged as the popular face of the resurgent real estate industry, whose towering skylines – so adored by Hollywood – became totemic of American greatness in its autumnal phase.

For the better part of three decades, this increasingly baroque financial system succeeded in restoring dynamism to the world economy, propelling the US beyond a sputtering Soviet regime into the position of uncontested global hegemon. And as the oil and stagflation crises retreated from view, it is perhaps not that surprising that faith in the FIRE sector’s new methods became so strong that creditors began to think themselves so cybernetically insured against loss that they lent in increasingly blithe and unstinting fashion.

It was in this climate of technocratic hubris that Fukuyama sketched out his thesis, one that expressed the dominant structure of feeling then prevailing in elite circles: The common sense of the period all but dictated that a universal “evolutionary pattern” was just then culminating in the globalization of liberal democracy, as “technologically driven capitalism … free[ed itself] of internal contradictions” (Fukuyama 1993: 91; xi).

These dreams seem all the more ironic now that one of the FIRE sector’s most notorious figures has begun to wreak havoc with the signal institutions of liberal democracy, questioning the accuracy of the ballot, wielding executive orders in madcap and draconian fashion, intimidating the judiciary, and attempting to bludgeon the free press into abject submission. The ironies deepen when we recall that it was the increasingly risky expansion of the FIRE sector that triggered the 2008 financial crisis, as the securitization of subprime mortgages opened the door to that last round of dispossession that underlies so much of today’s anti-establishment discontent.

The ramifying consequences of the 2008 financial crisis were evident in this electoral cycle as we saw the two candidates periodically breaking away from the familiar battery of appeals to the middle-class homeowner, to take time to address a dispossessed and precariously employed “working class” who had swelled to such an extent that their political significance could no longer be ignored.

Yet in its resurrection the figure of the worker seemed to have undergone a subtle transformation. In its return to the mainstage of electoral politics, talk of the worker functioned less as a metonym for the workers movement, and more as a shorthand for the plight of the downwardly mobile “worker-citizen,” one who could no longer count on social state protections, whose stake in the real estate market was gone or imperiled, but who was still the bearer of the full legal rights and privileges of the citizen.

To understand the increasingly reactionary disposition of this citizen-worker we have to grasp the long downturn’s ongoing effects on the technical and demographic composition of the real economy. This effort again finds us tacking back to the 1970s, to the last great crisis in the capitalist world system, when attempts to restore dynamism to the global economy saw industrial capital fighting to break free of the constraints that social democracy had placed on its agency, unleashing a two-pronged assault on labor. Capital flight saw manufacturing plants flee the blue-collar heartlands, as industry reconstituted its industrial base in the emerging economies where it could exploit a labor force that enjoyed far fewer legal protections. And at one and the same time as the Thatcher and Reagan administrations drove through the legislation that facilitated and policed this new round of capital flight – a series of legislative actions that also undergirded the FIRE sector’s emergence as the new motor of economic dynamism – manufacturers also fended off the labor movement from within, introducing a new round of automation that saw labor’s relative share in the productive process decline, further securing factories against sabotage and slowdown.

Research collective Endnotes sums up the prevailing political fallout of this double-fronted assault:

Industrial output continues to swell, but is no longer associated with rapid increases in industrial employment … In this context, masses of proletarians, particularly in countries with young workforces, are not finding steady work; many of them have been shunted from the labour market, surviving only by means of informal economic activity (Endnotes 2015)

The use of the term “shunted” here evokes the language of Stuart Hall’s Policing the Crisis. And in tracking the early effects of this “shunting from the labour market” Hall identified that the policing of deindustrialization’s dispossessed broke differentially along racial lines. As the economy contracted, white Britons closed ranks, consigning immigrant communities to a greater share of the joblessness that capital flight was leaving behind it. Writing that race was “one of the main mechanisms, by which, inside and outside the work-place itself, th[e] reproduction of an internally divided labour force [was] accomplished” (Hall et al. 1982 [1978]: 346), Hall detailed the advantages that the dominant classes gleaned from these divisions:

The ‘benefits’ … must therefore be reckoned to include not only the direct and indirect exploitation of the colonial economies overseas, and the vital supplement which this colonial work-force made to the indigenous labour force in the period of economic expansion, but also the internal divisions and conflicts which have kept that labour force segregated along racial lines in a period of economic recession and decline – at a time when the unity of the class as a whole, alone, could have pushed the country into an economic ‘solution’ other than that of unemployment, short-time, cuts in the wage packet and the social wage. (Hall et al. 1982: 346)

Having identified these developing tendencies – and their role in keeping the “unity of the class as a whole” at bay – Hall went on to explore how black Britons had begun to adapt to their entrapment in the grey and black economies. Explaining the concept of hustling for the benefit of a predominantly white readership, he wrote:

The hustle is as common, necessary and familiar a survival strategy for ‘colony’ dweller’s as it is alien and strange to those who know nothing of it … Hustlers live by their wits. So they are obliged to move around from one terrain to another, to desert old hustles and set up new ones in order to stay in the game. From time to time, ‘the game’ may involve rackets, pimping, or petty theft. But hustlers are also the people who sustain the connections and keep the infrastructure of ‘colony’ life intact. They are people who always know somebody, who can get things done, have access to scarce goods, who can ‘deal’ and service the less-respectable ‘needs’ of the respectable end of ‘colony’ society. They hang out around the clubs, organise the blues parties, set the domino game up, know what day the illegal white rum distilleries produce. They work the system; they also make it work … When the going is good, hustlers are men about the street with style, visibly displaying their temporary good fortune: ‘cool cats.’ (Hall et al. 1982: 351-2)

Of course in the days since he offered this account, hip hop’s rise to pop cultural dominance has made the swaggering resourcefulness of the hustler part of the cultural fabric of millennial experience. Few under the age of forty are not intimately familiar with hip hop’s virtuosic chronicling of Black America’s experience of the racialized policing of the long downturn. Part of the enduring value of Hall’s work lies in its ability to tie hip hop’s signature tropes and stances to the determinations against which they emerged, as the policing of capital’s real movement subjected the black proletariat to the worst effects of this new round of capital flight and automation.

Indeed, in retrospect, it seems that NWA, rather than Hasselhoff, would have been a fitter avatar of the inequities that globalization scattered in its wake as it ground the labor movement beneath its heel. For while Hasselhoff’s words at the Berlin Wall implied that freedom had descended on the former Soviet bloc in a moment of decisive apotheosis, in NWA’s language freedom was difficult to attain; indeed, it was wrestled from the system in the context of an unremitting struggle with occupying powers determined to maintain existing inequities:

Fucking with me cause I’m a teenager

With a little bit of gold and a pager

Searching my car, looking for the product

Thinking every nigga is selling narcotics

You’d rather see me in the pen

Than me and Lorenzo rolling in a Benz-o

In the crosshairs of the carceral state it was more than evident that history and the struggle for emancipation was far from over.

Still, when Hall sketched out his typology of the hustler he, like Davis, would probably have been surprised by the uncanniness of subsequent developments. For at one and the same time as policing practices trended along the lines he identified – with a massively disproportionate number of black Americans subject to incarceration and unemployment – we also saw hip hop’s hustler swagger its way deep into the heart of the American culture industry. So deep was the penetration that one of hip hop’s most celebrated dons would one day take to the stage of Carnegie Hall, backed by a 36-piece orchestra, in a full tuxedo and tie, to make a boast of a rags-to-riches tale that dwarfed anything that Dickens ever conceived:

Momma ain’t raised no fool

Put me anywhere on God’s green earth,

I’ll triple my worth

Motherfucker, I, will, not, lose

I sell ice in the winter, I sell fire in hell

I am a hustler baby, I’ll sell water to a well

I was born to get cake, move on and switch states

Cop the coupe with the roof, gone and switch plates

The epic scale of Jay Z’s biography – from resourceful street kid slinging rocks on the corner, to owner of music streaming service valued at $600 million – charts one self-defined hustler’s traversal of the vast wealth disparities that have characterized the global economy in the wake of the belle époque.

We might pause for a moment here to consider the sociological significance of hip hop’s massive contemporary appeal. Indeed, it might not be too much of a stretch of the imagination to suggest that part of what has driven these accounts of life in the game to the top of the Hot 100 is precisely the more widespread generalization of the conditions of precarity and disenfranchisement that this genre has spent the bulk of its existence recounting and resisting. As the state continues to scale back on the welfarist commitments of the postwar order, and as yet another wave of automation sees the world system further unable to absorb labour into the productive process, a life in the black or grey economy is a very real prospect for increasing numbers of the world’s people. Endnotes write at another juncture:

The social links that hold people together in the modern world, even if in positions of subjugation, are fraying, and in some places, have broken entirely. All of this is taking place on a planet that is heating up, with concentrations of greenhouse gases rising rapidly since 1950. The connection between global warming and swelling industrial output is clear. The factory system is not the kernel of a future society, but a machine producing no-future. (Endnotes 2015)

A poignant statement in light of the last electoral cycle, as the Trump campaign implicitly configured the 1950s “factory system” as the locus of America’s lost greatness, promising to “return” the US to a weird Disneyland recapitulation of its Fordist heyday. And as Trump’s executive actions against environmental and energy agencies have demonstrated in the weeks since his inauguration, this back-to-the-future ride will not tolerate any slowdown or inhibition of its propulsive thrust toward “no-future.”

Endnotes write that today’s left is prone to approach the worker’s movement with the “latecomers’ melancholy reverence” (Endnotes 2015) – a striking phrase that eerily anticipates Trump’s appeal to America’s erstwhile greatness. And these affinities seem capable of identifying a key problematic that has handed the Rust Belt over to Trump, and the British postindustrial zones to the Leave Campaign. For while the architects of globalization succeeded in decimating the worker’s movement, they were markedly less successful in their efforts to subordinate the sovereignty of the nation state to the rigors of transnational law. And thus as citizen-workers look for protection against immiseration, many seem increasingly willing to approve statist measures to both expel noncitizens who “unfairly compete” for scarce jobs, and introduce protectionist regimes designed to shield the nativist worker from the threat of international competition. Unable to organize themselves in a united internationalist front against exploitation, it is hardly surprising that the downwardly mobile worker-citizens of today are instead willing to fall back on the state’s promises to negotiate favorable “deals” on their behalf.

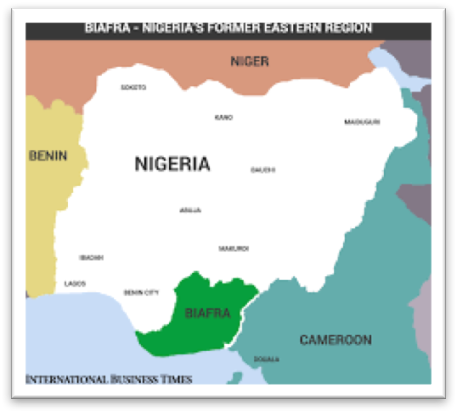

The background to these tendencies seems to be the declining viability of the global development narrative that has attended postwar international policymaking since the Bretton Woods Agreement. In the context of secular stagnation and economic contraction, advanced economies have been forced to rely on our era’s signature admixture of debt and austerity, scaling back on welfarist provisions even as the nation state continues to function as a macroeconomic stimulator and a guarantor of private property. And increasingly, as development of the world system’s “peripheral” regions also stalls (Barone 2015), the core economies appear to be bracing themselves to resist a rising tide of economic and climate migration. It seems that population growth, economic growth, and industrial productivity have fallen out of sync to such a profound extent that we are increasingly “experiencing modernization of industry without modernity’s attendant social forms: without, that is, the institutional, social, cultural features associated with development, such as universal public education, democratic state institutions” and the humanitarian defense of human rights (Brouillette and Thomas 2016: 511).

Yet rather than identify the newness of this geopolitical situation, political discourse on these matters more often coalesces around an introverted and melancholic nationalism that understands the immiseration of the worker-citizen in relation to vague but impassioned narratives of national decline. It is telling that Trump’s notorious baseball cap evokes the popular affluence of the belle époque through the allusive figure of “greatness,” a sleight of hand that evades the tricky question of how exactly one goes about turning back the clock on the technological development of the forces of production. For even if Trump’s protectionist policies do manage to lure back some manufacturing plants, the fixed to variable capital ratio will not be as favorable as it was back in the days when America was “great,” which is to say, when it was Fordist.

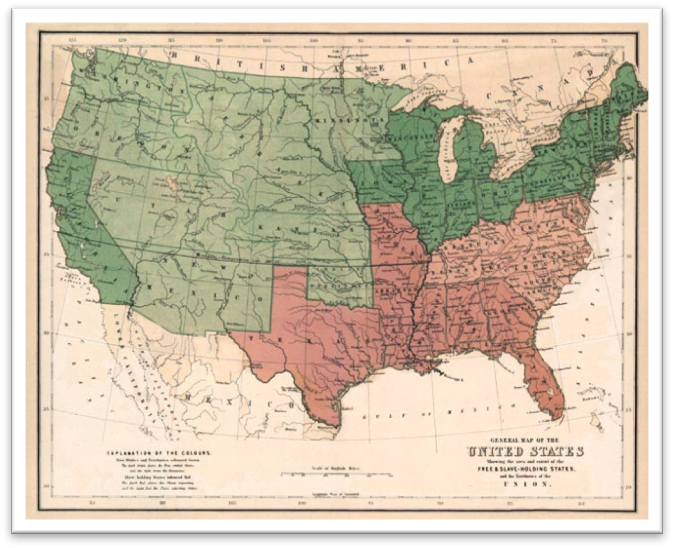

Appeals to the figure of the precarious citizen-worker – more often figured in the guise of Thatcher’s “individual, and his family” – thus became a common feature of both campaigns. Yet in Clinton’s case we witnessed the strange spectacle of an establishment standard-bearer attempting to patch together, ad hoc, a fuzzily defined platform that alternately gestured toward the maintenance of the status quo, and toward the construction of a newly “social democratic” pluralism. Trump, meanwhile, staked out a clearly defined appeal to white nativist protectionism, one that was capable of uniting a large cross section of white America around the prospect of a Fordist “restoration,” one that sought to assert the rights and security of the white worker-citizen in the face of intensifying global economic malaise.

In so doing, the Trump campaign amplified a strategy that has been a mainstay of advanced economies in times of crisis throughout the postwar period. Hall describes this strategy in relation to the structural function that migrant workers performed for British industry from the early-1950s to the mid-1970s:

In the early 1950s, when British industry was expanding and undermanned, labour was sucked in from the surplus labour of the Caribbean and Asian subcontinent. The correlation in this period between numbers of immigrant workers and employment vacancies is uncannily close. In periods of recession, and especially in the present phase, the numbers of immigrants have fallen; fewer are coming in, and a higher proportion of those already here are shunted into unemployment. In short, the ‘supply’ of black labour in employment has risen and fallen in direct relation to the needs of British capital. (Hall et al. 1982: 343)

On the one hand, Trump’s wall, Brexit, and the broader European resistance to the Schengen Agreement, faithfully reproduce the pattern that Hall identified, as global conditions of economic contraction have triggered a rising tide of anti-immigration policies.

Yet what separates the dynamics that Hall describes from those that are unfolding around us now, is the extent to which Trump’s anti-immigration policies are also a feature of a larger enthnonationalist projectionist program, one that signals a full-blooded return to the so-called “beggar-thy-neighbor” economic strategies that last openly prevailed prior to the advent of the Bretton Woods Agreement.

Writing in 1937, British economist Joan Robinson argued that “in times of worldwide unemployment, it is indeed possible for one country to increase its employment and total output by increasing its trade balance at the expense of other countries. She coined the phrase ‘beggar-thy-neighbor’ to describe such policies” (Pasinetti 2008 [1987]). Robinson itemized four beggar-thy-neighbor economic weapons: wage reductions, officially induced exchange depreciation, export subsidies, and import restrictions. In the last month the US government has publicly evoked most, if not all, of these weapons, either accusing other governments of using them against the US, or signaling its intention to use them itself.[i] It is worth stressing that this is more of an escalation of already-existing dynamics than a complete bolt out of the blue – i.e. beggar-thy-neighbor strategies have been quietly on the rise for a decade or more (Barone 2015) – but the additional level of unvarnished aggression that Trump has introduced into the picture cannot but result in further escalations. The underlying dynamic is one in which – under the prevailing conditions of secular stagnation – economic growth risks becoming a zero-sum game, such that the growth of one nation is always talking place at the expense of another.

Here Robinson’s explanation of the likely geopolitical fallout of beggar-thy-neighbor economics is worth remembering. Robinson wrote that “as soon as one country succeeds in increasing its trade balance at the expense of the rest, others retaliate” and among the economic effects of this cycle of retaliation is a reduced volume of international trade (Robinson 1947, 156). There are affective consequences to these cycles of retaliation and these increasingly isolationist tendencies. Indeed, Robinson cautions that such policies can “add fuel to the fire” of economic nationalism, as trade wars push nations to the brink of open hostilities (Robinson 1947: 157).

It should be noted that the intellectual circles that fostered this new ethnonationalism are not averse to an escalation of international armed conflict. Indeed, Steve Bannon is on record as thinking a war with China “inevitable” within the next ten years (Hass 2017). Much like Russia’s Alexander Dugin, Bannon subscribes to a world-historical vision that anticipates the onset of another great war, one that will serve as the crucible from which a revived Judeo-Christian culture will emerge victorious:

But I strongly believe that whatever the causes of the current drive to the caliphate was — and we can debate them, and people can try to deconstruct them — we have to face a very unpleasant fact. And that unpleasant fact is that there is a major war brewing, a war that’s already global. It’s going global in scale, and today’s technology, today’s media, today’s access to weapons of mass destruction, it’s going to lead to a global conflict that I believe has to be confronted today. Every day that we refuse to look at this as what it is, and the scale of it, and really the viciousness of it, will be a day where you will rue that we didn’t act (qtd. Feder 2016)

We are, at this juncture, a long way from the condition of universal post-historical secularism that Fukuyama anticipated. Indeed, the surprisingly pervasive appeal of Dugin and Bannon’s millennial creeds seems to have done much to consolidate Trump’s white American base, where a paranoiac strain of conservative religiosity has gained a powerful foothold. In a widely circulated address to a Vatican conference, Bannon appealed to the old counter-reformation concept of the “Church Militant” in an effort to recruit foot soldiers for an apocalyptic culture war, one that was to unfold, simultaneously, on domestic and geopolitical fronts:

And we’re at the very beginning stages of a very brutal and bloody conflict, of which if the people in this room, the people in the church, do not bind together and really form what I feel is an aspect of the church militant, to really be able to not just stand with our beliefs, but to fight for our beliefs against this new barbarity that’s starting, that will completely eradicate everything that we’ve been bequeathed over the last 2,000, 2,500 years. (qtd. Feder 2016)

On the international stage, the prime bête noire was the “new barbarity” of “jihadist Islamic fascism” (qtd. Feder 2016). Yet in the same speech in which he made use of this profoundly ironic terminology, Bannon also trained his ire on the architects of globalization, producing a strange taxonomy of “capitalisms” that distinguished between the “enlightened capitalism” of the “Judeo-Christian West,” and the new “crony capitalism” of Davos, one that a “younger generation” had “gravitate[d] to under this kind of rubric of personal freedom” (qtd. Feder 2016).

As Bannon’s remarks make plain, conservative America’s Christianity and its post-Fordist nostalgia are now all tangled up in each other in ways that speak both to the impact that automation and deindustrialization have had on traditional gender norms, and to the much more widely pervasive and ambient sense of melancholy that results from living under the setting sun of a declining hegemon. Indeed, there is a case to be made that the extinction of the blue-collar “oedipal wage,” and the corresponding structural obsolescence of the “traditional” nuclear family, have been key catalysts of the US’s culture wars. For while conservatives have targeted changing gender norms as “dangerous” symptom of liberalism’s lapsarian hubris, what is actually taking place is arguably much better understood as another case of all that was solid melting into air. Sarah Brouillette puts the matter this way:

In our current situation of economic turmoil and stagnation, the reproduction of productive labor in couple-based households is no longer a necessity everywhere –indeed, in some countries, the difficulty of keeping people working and keeping the unemployed engaged in work-like activities worries governments greatly, hence conversations about the possibility of a Universal Basic Income. At the same time, an expanding service sector handles some of what used to keep people too busy to develop multiple relationships: housekeeping, childrearing, and elder care, for example. Under these circumstances, it is more possible than ever for ‘alternative’ ways of being to come to the fore, with some even achieving mainstream respectability: think gay marriage, affective disinvestment in parenting, non-couple coparenting, moving back in with your parents, and ‘conscious uncoupling.’ Flip the coin, and the dwindling of the blue-collar industrial workforce, the expansion of domestic and affective caring work in the service sector, and the creeping obsolescence of the traditional nuclear family, have been crucial drivers of the hyper-conservative Men’s Rights Activist or ‘alt-right’ masculinist backlash against changing norms. (Brouillette 2017)

This is not, however, how this would-be Church Militant understands the situation. And under the leadership of figures like Bannon it has taken up the project of trying to discipline gender norms back into alignment with its particular hierarchy of values and prohibitions, a project that reveals a latently theocratic dimension to the American and Russian branches of ethnonationalism.

Indeed, insofar as the Trump administration continues to signal its commitment to a new counter-reformation – via the metonyms of its opposition to abortion, trans rights, and gay marriage, and its virulent hostility to Islam – it can count on a large base of support among white American Christians, many of whom seem willing to overlook the refugee camps, the prisons, and the ecocide, just so long as gender norms and national holidays are better aligned with the niceties of canon law. The Trump era thus seems set to catalyze a struggle for the soul of Christianity, as clericalist traditionalists – ever vulnerable to allure of state power – do battle with a charismatic and decidedly anti-clericalist, anti-capitalist Pope:

In one of the cardinal’s antechambers, amid religious statues and book-lined walls, Cardinal Burke and Mr. Bannon – who is now President Trump’s anti-establishment eminence – bonded over their shared worldview. They saw Islam as threatening to overrun a prostrate West weakened by the erosion of traditional Christian values, and viewed themselves as unjustly ostracized by out-of-touch political elites. ‘When you recognize someone who has sacrificed in order to remain true to his principles and who is fighting the same kind of battles in the cultural arena, in a different section of the battlefield, I’m not surprised there is a meeting of hearts,’ said Benjamin Harnwell, a confidant of Cardinal Burke who arranged the 2014 meeting. (Pierce 2017)

And thus as the Trump admiration attempts to consolidates its base, it seems set to lean hard on the far right flank of conservative Christianity, as it positions its reactionary, xenophobic, and ecocidal mandate as a noble crusade to save “the West” from external and internal enemies. Early signs suggest that attacks on the press and the liberal academy will intensify in the coming days, as Bannon and company turn their attention to the “enemies within.” The structural position of the press and the academy thus seems set to undergo a seismic shift. Accustomed to offering ambivalent but compliant critiques of neoliberal globalism, the principle organs of the bourgeois sociolect now find themselves thrust into a battle that they had thought consigned to the annals of history, undertaking harried resistance on terrain that is not of their own choosing. The radicalization of the press is already underway as we pass through the looking glass into a world where Teen Vogue and Cosmopolitan join The Guardian in drumming up support for a general strike. And as the Trump administration’s cuts to the NEA and NEH budget take hold, it appears that the liberal humanist academy will have little choice but to join the fray, drawing its post-critical turn to a panicked conclusion.

It seems that for those who have been shielded from the harsher effects of globalization, it is hard not to feel nostalgic for the days when it was possible to indulge – however ambivalently – in Fukuyama’s dream. Where we go from here is extremely unclear, and one obviously feels dwarfed by the massive scale of these developments. But I suspect we should not spend too long grieving the loss of Fukuyama’s political horizon, for it helped to bring us to the place where we now stand, occluding the intensifying inequities that have resulted from the long downturn, developments that have opened the door to this new round of ethnonationalist insurgency. The Trump administration’s erratic brand of nascent fascism is a very real and present danger, one that we would be naive not to resist by whatever means we are able, but we also have to keep firmly in mind that this administration is not the sole source of our problems. We are in the grip of another of the violent and eruptive crises that capitalism has, throughout its long history, repeatedly thrust upon us.

And if we find ourselves still burning a candle for some vestige of that dream of unity that Lennon cribbed from the chauvinistic language of the postwar reconstruction, then that may entail putting ourselves on the line in ways that we have been little accustomed to do in recent years. The fight is coming to us whether we like it or not. And in fighting back we will need to rediscover political horizons that extend far beyond the concerns of the individual and his family.

The value of an individual life a credo they taught us

to instill fear, and inaction, ‘you only live once’

a fog in our eyes, we are

endless as the sea, not separate, we die

a million times a day, we are born

a million times, each breath life and death:

get up, put on your shoes, get

started, someone will finish (di Prima 2007 [1971]: 8)

David Thomas is a Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate Scholar in the Department of English at Carleton University. His thesis explores narrative culture in post-workerist Britain, and unfolds around the twin foci of class and climate change.

References

Barone, Barbara. “Protectionism in the G20.” Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies. European Union, Belgium: 2015 https://www.academia.edu/12266435/ Protectionism_in_G20_2015_

Brenner, Robert. Economics of Global Turbulence. London: Verso, 2006.

Brouillette, Sarah. “A feminist communist killjoy reads Future Sex,” Public Books. Forthcoming 6 March 2017.

Brouillette, Sarah, and David Thomas. “Forum: Combined and Uneven Development,” Comparative Literature Studies, No 53, 3, 2016.

Carter, Shawn. You Don’t Know. New York: Roc-A-Fella Records, 2001.

Carter, Shawn. “You Don’t Know Lyrics,” Genius, 24 Feb 2017: https://genius.com/Jay-z-u- dont-know-lyrics

Davis, Mike. “Urban Renaissance and the Spirit of Postmodernism,” New Left Review, No. 151, May – June 1985: https://newleftreview.org/I/151/mike-davis-urban-renaissance-and-the-spirit-of-postmodernism

Di Prima, Diane. Revolutionary Letters. San Francisco: Last Gasp of San Francisco, 2007.

Endnotes. “A History of Separation,” Endnotes 4, October 2015: https://endnotes.org.uk/issues/4/en/endnotes-preface

Feder, J. Lester. “This Is How Steve Bannon Sees The Entire World,” Buzzfeed, 16 Nov 2016: https://www.buzzfeed.com/lesterfeder/this-is-how-steve-bannon-sees-the-entire-world?utm_term=.yxR8RK2gV#.sh1Q6P02E

Fukuyama, Francis. “The End of History?” The National Interest, No. 16, 1989: 3-18.

Fukuyama, Francis. The End of History and The Last Man. New York: Harper Perennial, 1993.

Fukuyama, Francis. “The History at the End of History,” Guardian, 3 April 2007: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2007/apr/03/thehistoryattheendofhist

Haas, Benjamin. “Steve Bannon: We’re going to war in the South China Sea … no doubt,” Guardian, 02 Feb 2017: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/feb/02/steve-bannon-donald-trump-war-south-china-sea-no-doubt

Hall, Stuart, Chas Critcher, Tony Jefferson, John Clarke, and Brian Roberts. Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order. Hong Kong: MacMillan Press, 1982.

Jackson, O’Shea, Andre Romell Young, Lorenzo Jerald Patterson, Harry Lamar III Whitaker.

Fuck Tha Police. Los Angeles: Priority Records, 1988.

Jackson, O’Shea, Andre Romell Young, Lorenzo Jerald Patterson, Harry Lamar III Whitaker.

“Fuck Tha Police Lyrics,” Genius, 24 Feb 2017:https://genius.com/Nwa-fuck-tha-police-lyrics

Lennon, John, and Barrie Carson Turner. Imagine. EMI, 1971.

Pasinetti, Luigi L. “Robinson, Joan Violet (1903–1983).” The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Second Edition. Eds. Steven N. Durlauf and Lawrence E. Blume. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics Online. Palgrave Macmillan. 14 February 2017: http://www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id= pde2008_R000166> doi:10.1057/9780230226203.1450

Robinson, Joan. “Beggar-My-Neighbor Remedies for Unemployment,” Essays in the Theory of Employment. Oxford: Basil Blackwell & Mott, 1947: 156-172.

Pierce, Charles C. “For His Next Trick, Steve Bannon Will Undermine the Pope.” Esquire. 07 Feb 2017: http://www.esquire.com/news-politics/politics/news/a52901/bannon-pope-francis/

Wilson, Scot. “Violence and Love (in Which Yoko Ono Encourages Slavoj Zizek to give Peace a Chance).” Violence and the Limits of Representation. Matthews, Graham, and Sam Goodman, eds. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013: 28-48.

Notes

[i] For examples of the Trump administration’s remarks on currency devaluation see:

http://asia.nikkei.com/Markets/Currencies/Trump-singles-out-Japan-China-Germany-for-currency-attack; and for their current approach to export subsidies, and import restrictions consult: http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2017/02/economist-explains-9 and http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-38764079