by Robert T. Tally Jr.

This essay has been peer-reviewed by the boundary 2 editorial board.

I

The 1950 U.S. Senate race in North Carolina was fiercely contested, featuring what even then was understood by many to be the opposed ideological trajectories of Southern politics: that of a seemingly progressive, “New South,” characterized by its support for modernization, industry, and above all civil rights (or, at least, improvements to a system of racial inequality) on the on hand, and that of a profoundly conservative tradition resistant to such change, particularly with respect to civil rights, on the other. The unelected incumbent, appointed by the governor after the death of Senator J. Melville Broughton a year earlier, Frank Porter Graham was notoriously progressive, the former president of the University of North Carolina and a proponent of desegregation. The challenger was Willis Smith, mentor to later longtime conservative senator Jesse Helms, who was himself an active campaigner for Smith in this race. At the time, this election was viewed as a turning point in North Carolinian, and perhaps even Southern, politics, so starkly was the ideological division drawn. The primary election—this being 1950, the Democratic primary was, in effect, the election, since no Republican nominee could possibly offer meaningful competition in November—was remarkably vitriolic, as Smith supporters played on the fears of bigots at every turn. (For example, one widely disseminated pro-Smith flyer announced “Frank Graham Favors Mingling of the Races.”) On May 26, a Graham supporter, the idealistic young major of Fayetteville took to the airwaves to castigate the Smith campaign for its repulsive rhetoric and divisive tactics:

Where the campaign should have been based on principles, they have attempted to assault personalities. Where the people needed light, they have brought a great darkness. Where they should have debated, they have debased. … Where reason was needed, they have goaded emotion. Where they should have invoked inspiration, they have whistled for the hounds of hate.

Decades before “dog-whistle politics” become a de facto political strategy throughout the South (and elsewhere, of course), J. O. Tally Jr. lamented the motives, and no doubt the effectiveness, of such an approach, which had made this the “most bitter, most unethical in North Carolina’s modern history.”[1]

That was my grandfather, then an ambitious, 29-year-old lawyer and politician, who must have seen himself as fairly representative of a New South intellectual and statesman. A graduate of Duke University with a law degree from Harvard, Joe Tally had returned from distinguished overseas service in the navy during World War II to teach law at Wake Forest University and to practice at the family firm before running for office in his hometown. His own career in electoral politics ended with a failed 1952 run for Congress, during which his moderate views on segregation likely amounted to an unpardonable sin for many voters in southeastern North Carolina, and he settled for alternative forms of civic and professional service, such as the Kiwanis Club, of which he later became international president. Others of Tally’s political circle had better fortunes with the voters. Terry Sanford, for example, went on to become the governor of North Carolina, then long-time president of Duke University, before returning the U.S. Senate in 1987 as perhaps the most liberal of the Southern senators. (Ah, to recall the time when an Al Gore was considered quite conservative!) Tally’s ex-wife, my grandmother Lura S. Tally, went on to serve five terms in the N.C. House and six in the Senate from 1973 to 1994, where she represented that liberal wing of the old Democratic Party, promoting legislation especially in support of elementary education, the environment, and the state’s Museum of Natural History. However, during the same period, former Smith acolyte Jesse Helms carried that banner into the U.S Senate in 1973, immediately becoming one of the most conservative members of Congress, hawkish in foreign policy, parsimonious in his domestic policy, and ever ready to protect the public from unsavory art in his attacks on the National Endowment for the Arts. Perhaps it is part of the legacy of the 1950 Senate campaign, but North Carolina had always seemed rather bi-polar in its politics, often maintaining a far-right-wing and a relatively liberal contingent in the U.S. Congress. That is, until recently. In the past decade, North Carolina, like all of the South and much of the country, has lurched ever rightward in politics and policies. Today, the spirit of the old conservatives of Willis Smith’s era reigns triumphant.

The same year that the Smith campaign allegedly “whistled for the hounds of hate” in order to secure an election over a liberal vanguard dead set on undermining traditional Southern values, another native North Carolinian lamented that those espousing belief in the such values had been forced out of the South. Speaking of the paradoxical fact that so many Southern Agrarians (including himself) had fled from their ancestral homeland to the urban North, there colonizing institutions like the University of Chicago, Richard M. Weaver proclaimed them “Agrarians in exile,” who had been rendered “homeless,” for “[t]he South no longer had a place for them, and flight to the North but completed an alienation long in progress.” Weaver explained that “the South has not shown much real capacity to fight modernism,” and added that “a large part of it is eager to succumb.”[2] For Weaver, the great Agrarians of the I’ll Take My Stand generation had been compelled to retreat in the face of those, like my grandparents, who in their “disloyalty” to “their section” of the United States exhibited “the disintegrative effects of modern liberalism.”[3] Contrary to appearances, Weaver found that the Southern values which undergirded his preferred form of cultural and political conservatism were under assault, and perhaps even waning, in the South. The baleful liberalism he saw as all but indomitable in the industrial North and Midwest was, in Weaver’s view, ineluctably encroaching on the sacred soil of the former Confederacy.

It is strange to look upon this scene from the vantage of the present. With the defeat of Senator Mary Landrieu in Louisiana’s December 6, 2014, run-off, there were no longer any Democrats from the Deep South in the U.S. Senate. And, as the 114th Congress convened in 2015, the U.S. House of Representatives contained no white Democrats from the Deep South, this for the first time in American history. Of course, the once “solid South” has been steadily trending ever more toward the Republicans since Brown vs. Board of Education, Governor Wallace’s “segregation forever,” and Richard Nixon’s notorious Southern strategy of the late 1960s. Native conservatism, gerrymandering, demographics, racial attitudes, and other factors have come into play, and the shift is therefore not wholly surprising, but the domination of the states of the former Confederacy by the Republican Party represents a sea-change in U.S. electoral politics. Furthermore, the hegemony of a certain Southern-styled conservatism within the Republican Party and, increasingly, within social, political, and cultural conservatism more generally marks a decisive movement away from not only the mid-century liberalism against which many Agrarians like Weaver railed, but also against the worldly neoconservatives like the elder President Bush whose embrace of a “new world order” elicited such fear and loathing from members of his own party in the early 1990s. The dominant strain of twenty-first-century political discourse in the United States is thus a variation on a sort of neo-Confederate, anti-modernist theme of the Agrarians,[4] or, rather, of Weaver, perhaps their greatest philosophical champion.

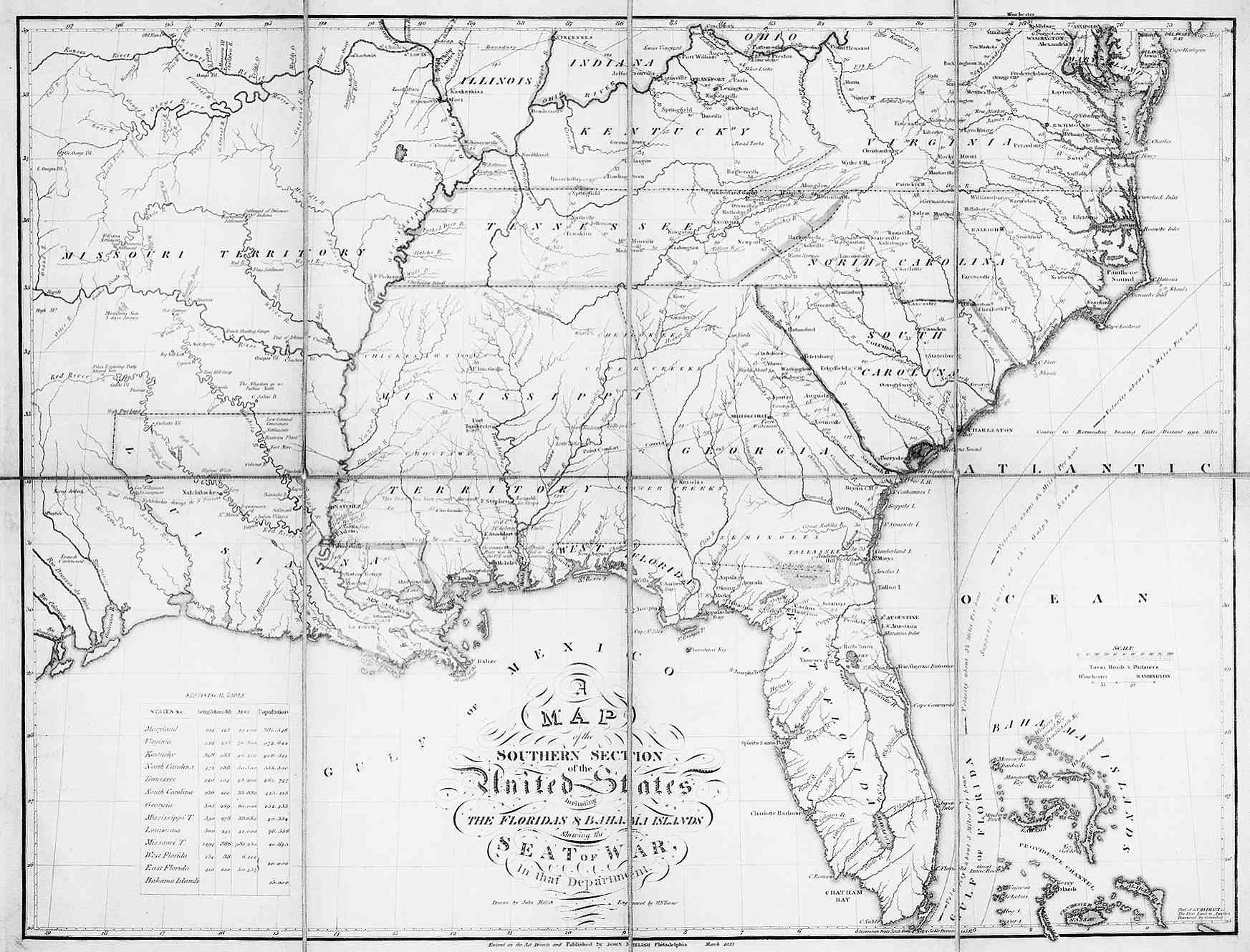

In this essay, I want to revisit the ideas of this mid-twentieth-century conservative theorist in an attempt to shed light on the origins of this distinctively American brand of conservatism in the twenty-first century. Weaver’s agrarian conservatism today seems both quaint or old-fashioned and yet disturbingly timely, as the rhetorical and intellectual force of his ideas seems all-too-real in the present social and political situation in the United States. Weaver’s mythic vision of the South, ironically, has come to symbolize the nation as a whole, at least from the perspective of many of the most influential conservative politicians and policy-makers today. As a result of what might be called the australization of American politics in recent years—that is, a political worldview increasingly coded according to identifiably “Southern” themes and icons, not to mention the growing influence of Southern and Southwestern politicians at the level of national government—we can see more clearly now the degree to which Weaver’s seemingly eccentric, often fantastic views have become not only mainstream, but perhaps even taken for granted, in 2015.[5] The “Southern Phoenix,” celebrated by Weaver for its ability to survive its own immolation and re-emerge from the ashes, now appears triumphant to a degree that the original Fugitives and Vanderbilt Agrarians could not have dreamed possible. And, as is so often the case when fantasies come to life, the result may be more frightening than even their worst nightmares forebode.

II

Outside of certain tightly circumscribed spaces of formally conservative thought such as that of the Liberty Fund, Richard M. Weaver may no longer be a household name. However, his writings and his legacy have been profoundly influential on conservative thinking, and he has been viewed as a sort of founding father or patron saint of the movement. The Heritage Foundation, for example, adopted the title of his totemic, 1948 critique of modern industrial society, Ideas Have Consequences, as its official motto when founded in 1973. A devoted student, literally and metaphorically, of the Southern Agrarians of the I’ll Take My Stand generation, Weaver embraced a certain “lost cause” view of the old Confederacy that informed his wide-ranging criticism of twentieth-century American and Western civilization. He viewed the antebellum South as the final flourishing of an idealized feudalism, doomed to fail as the forces of industry, science, and technology, together with ideological liberalism, secularism, and “equalitarianism,” undermined and ultimately destroyed its foundations. Weaver’s critique of modernity, like J. R. R. Tolkien’s, thus took the form of an almost fairy-story approach to history, in which a mythic past functioned as an exemplary model and as a foil to the lurid spectacle of the present cultural configuration, a balefully “modern” society characterized especially by its secularism, its embrace of scientific rationality, and its ineluctable process of industrialization. Weaver’s jeremiad is thus both dated, redolent of a certain pervasive interwar and postwar malaise, and enduring, as his rhetoric remains audible in social and political discourse today, particularly in all those election-year panegyrics to a “simpler” America, a paradisiacal place just over the temporal horizon, now most known to us by its mourned absence.

Weaver was born in Asheville, North Carolina, in 1910, but he moved to Lexington, Kentucky, as a small child, where he grew up “in the fine ‘bluegrass’ country,” as Donald Davidson noted,[6] and later received his bachelor’s degree from the University of Kentucky. In his autobiographical essay, pointedly titled “Up from Liberalism,” Weaver described the faculty there as “mostly earnest souls from the Middle Western universities, and many of them […] were, with or without knowing it, social democrats.”[7] This information is apparently supplied in order to explain Weaver’s own brief flirtation with the American Socialist Party upon graduation in 1932. Weaver then enrolled in graduate school at Vanderbilt, birthplace of I’ll Take My Stand in 1930 and thus ground zero of the literary or cultural movement by then known simply as “the Agrarians.” At Vanderbilt, Weaver studied directly under John Crowe Ransom, to whom The Southern Tradition at Bay was later dedicated, and he wrote a master’s thesis (“The Revolt Against Humanism: A Study of the New Critical Temper”), which criticized the “new” humanism of Irving Babbitt and Paul Elmer More, among others.[8] After receiving his M.A. degree, Weaver briefly taught at Texas A&M, but was repelled by its “rampant philistinism, abetted by technology, large-scale organization, and a complacent acceptance of success as the goal of life.”[9] Weaver entered graduate school at Louisiana State University, where his teachers included two other giants of the Agrarian and American literary traditions, Robert Penn Warren and Cleanth Brooks. The latter served as director for Weaver’s dissertation, a lengthy investigation and celebration of post-Civil War Southern literature and culture, evocatively (and provocatively) titled “The Confederate South, 1865–1910: A Study in the Survival of a Mind and Culture.” This book was released posthumously in 1968 as The Southern Tradition at Bay: A History of Postbellum Thought, and it may well be considered Weaver’s magnum opus, as I will discuss further below. After receiving his Ph.D., Weaver taught briefly at N.C. State University, before embracing “exile” at the University of Chicago, where he spent the remainder of his professional life, not counting the summers during which he returned to western North Carolina, apparently to replenish his reserves of authentic agrarian experience and to recapture the “lost capacity for wonder and enchantment.”[10] As it happens, Weaver’s celebratory vision of the Southern culture is comports all-too-well with that of a fantasy world.

Legend has it that the virulent anti-modernist eschewed such new-fangled technology as the tractor, yet he seemed to have little compunction about enjoying the convenience of the railroad and other amenities made possible by modern industrial societies. “Every spring, as soon as the last term paper was graded, he traveled by train to Weaverville [North Carolina, just north of Asheville], where he spent summers writing essays and books and plowing his patch of land with only the help of a mule-driven harness. Tractors, airplanes, automobiles, radios (and certainly television)—none of these gadgets of modern life were for Richard Weaver,” writes Joseph Scotchie, admiringly.[11] Yet Weaver also speaks about drinking coffee with pleasure, knowing well that Appalachia is not known for its cultivation of this crop. As with so much of the fantastic critique of modernity by reactionaries, there is an unexamined (perhaps even unseen) principle of selection that allows one to choose which parts of the modern world to tacitly accept, and which to ostentatiously jettison.

III

Weaver’s most significant and influential work published during his lifetime is undoubtedly Ideas Have Consequences, a title given by his editor at the University of Chicago Press but which Weaver had intended to call The Fearful Descent.[12] It is actually one of only three books published by Weaver during his own life; the others are The Ethics of Rhetoric (1953) and a textbook titled simply Composition: A Course in Writing and Rhetoric (1957). Weaver recalled that Ideas Have Consequences originated in his own rather despondent musings about the state of Western Civilization in the waning months of World War II, as he experienced “progressive disillusionment” over the way the war had been conducted, and he began to wonder “whether it would not be possible to deduce, from fundamental causes, the fallacies of modern life and thinking that had produced this holocaust and would insure others.”[13] Weaver’s bold, perhaps bizarre, premise was that the civilizational crisis in the twentieth century could be traced to a much earlier philosophical turning point in the trajectory of Western thought, namely the proto-scientific nominalism of William of Occam. Weaver draws a direct line from Occam’s Razor to the most deleterious effects (in his view) of modern empiricism, materialism, and egalitarianism.

For Weaver, humanity took a wrong turn in the fourteenth century when it allegedly embraced Occam’s Razor as the guiding principle of all logical inquiry, thus condemning mankind to a sort of secular, narrow, bean-counting approach to both the natural and social worlds. Referring obliquely to Macbeth’s encounter with the weird sisters in Shakespeare’s tragedy, Weaver asserts that

Western man made an evil decision, which has become the efficient and final cause of other evil decisions. Have we forgotten our encounter with the witches on the heath? It occurred in the late fourteenth century, and what the witches said to the protagonist of this drama was that man could realize himself more fully if he would only abandon his belief in the existence of transcendentals. The powers of darkness were working subtly, as always, and they couched this proposition in the seemingly innocent form of an attack upon universals. The defeat of logical realism in the great medieval debate was the crucial event in the history of Western culture; from this flowed those acts which issue now in modern decadence.[14]

What follows from this is a lengthy, somewhat disjointed analysis of “the dissolution of the West,” which will include not only the critique of philosophical tendencies or declining moral codes, but also attacks on egotism in art, jazz music, and other forms of popular entertainments. It is almost a right-wing version of the near-contemporaneous Dialectic of Enlightenment, except that Weaver would not have imagined “Enlightenment” to have suggested anything other than “disaster triumphant” to begin with, and Horkheimer and Adorno was all too wary of the latent and manifest significance of the jargon of authenticity as enunciated by writers like Weaver.[15]

Although Ideas Have Consequences is not overtly “Southern” in any way, Weaver’s medievalism, which was developed not according to any deeply philological study of premodern texts (à la Tolkien) but rather from his own sense of that late flowering of chivalry in the antebellum South, indicates the degree to which his discussion of the West’s decline is actually tied to his view of the lost cause of the Confederacy. The first six chapters of Ideas Have Consequences constitute a fairly scattershot series of observations on “the various stages of modern man’s descent into chaos,” which began with his having yielded to materialism in the fourteenth century, and which in turn paved the way for the “egotism and social anarchy of the present world.”[16] The final three chapters, by contrast, are intended as restorative. That is, in them Weaver attempts to delineate the ways that modern man might resist these tendencies, reversing the movement of history, and reaping the rewards of a legacy that would presumably have flourished had only the pre-Occam metaphysical tendency ultimately prevailed. In a 1957 essay in the National Review, Weaver claimed that, contrary to the assertions of liberals, the conservatives were not so much in favor of “turning the clocks back” as “setting the clocks right.”[17] Not surprisingly, Weaver’s three prescriptions in Ideas Have Consequences would neatly align with the fantastic, medieval, or feudal system he had imagined as the dominant form of social organization in the antebellum South, although he does not highlight his regional allegiance in this, a work purportedly devoted to the study of (Western) civilization as a whole.

The first is the principle of private property, which Weaver takes to be “the last metaphysical right” available to modern man. That is, while “the ordinances of religion, the prerogatives of sex and of vocation” were “swept away by materialism” (specifically, the Reformation, changing social values, and so on), “the relationship of a man to his own has until the present largely escaped attack.”[18] Weaver calls the right to private property a “metaphysical right” because “it does not depend on social usefulness. […] It is a self-justifying right, which until lately was not called upon to show in the forum how its ‘services’ warranted its continuance in a state dedicated to collective well-being.”[19] Private property, which Weaver likens to “the philosophical concept of substance,” is depicted as providing a foundation for the renewed sense of self and being in the world. The second principle is “the power of the word”: “After securing a place in the world from which to fight, we should turn our attention to the matter of language.”[20] Weaver offers a critique of semantics as itself simply a form of nominalism, while arguing for an education in poetics and rhetoric as necessary to reclaim one’s connection to the absolute, while also remaining critical of the abuses of language in modern culture. Finally, Weaver concludes with a chapter on “piety and justice,” in which he argues that the piety, “a discipline of the will through respect,” makes justice possible by allowing man to transcend egotism with respect to three things: nature, other people, and the past.[21] Fundamentally, for Weaver, this piety issues from a chivalric tradition that he imagines as the only real hope for a reformation of the twentieth-century blasted by war, spiritually desolate, and (he does not shrink from using the term) “evil.” What is needed, Weaver concludes in the book’s final line, is “a passionate reaction, like that which flowered in the chivalry and spirituality of the Middle Ages.”[22]

As it happened, there was a place in the United States which had previously held, and in 1948 perhaps still maintained, this medieval worldview. Weaver’s beloved South, even though it was under siege from without by the forces of modernity and in peril from within by a generation of would-be modernizers, retained the virtues of an evanescing feudal tradition, which might somehow be recovered and brought into the service of civilization itself. Indeed, Weaver’s first book-length work, which only appeared in print after his death, was an elaborate examination and strident defense of this chivalric culture that once flourished beneath the Mason and Dixon line. If only its message could be distilled and disseminated, this Southern tradition might redeem the entirety of the West.

IV

The Southern Tradition at Bay occupies a unique and important place in Weaver’s corpus. Based on his doctoral thesis but published five years after his death, the book can be read as being representative of his “early” thinking on the subject and as a sort of summa of his entire literary and philosophical program at the same time. Many of the ideas that Weaver here identifies as Southern are clearly connected to those he celebrates in Ideas Have Consequences. For example, Weaver’s elaboration of the “mind” of the Old South focused on four distinctive but interrelated characteristics: the feudal system, the code of chivalry, the education of the gentleman, and the older religiousness, by which Weaver meant a non-creedal religiosity. Combined, these four factors distinguished the unique culture of the “section,” clearly differentiating its heritage from that of other parts of the United States.[23]

Weaver’s medievalism, as I mentioned before, is not rooted in the formal study of the history, philology, or philosophy of the European Middle Ages, although he draws upon certain imagery from its time and place. One might argue that Weaver’s project is literally quixotic, inasmuch as he figuratively dons the rusty armor of a bygone age to tilt at windmills which he imagines to be giants, but in an effort “in this iron age of ours to revive the age of gold or, as it is generally called, the golden age.”[24] Weaver’s tone is simultaneously elegiac and recalcitrant, mourning the lost cause or the waning of a glorious past and ardently defending its values in the present, fallen state of the world. Methodologically, Weaver’s approach is to gather selectively then-contemporary accounts, including public proclamations and individual diaries—or, often, a combination of the two, in the form of published memoirs—as well as more recent historical studies, then add his own assessments of their currency (i.e., in 1943) as evidence of an enduring, twentieth century “Mind of the South.”[25] Weaver somewhat disingenuously cautions that,

In presenting evidence that this is the traditional mind of the South, I am letting the contemporaries speak. They will seldom offer whole philosophies, and sometimes the trend of thought is clear only in the light of context; yet together they express the mind of a religious agrarian order in struggle against the forces of modernism.[26]

Needless to say, perhaps, but such a collective “mind” is likely not to be discovered if the historian were to cast the nets of his research more widely.[27] By identifying only those “true” Southerners whose opinions can thereafter be identified as authentic, Weaver anticipates all of our current politicians and pundits who seem to be forever deferring to these mythical “real Americans” whose viewpoints are curiously at odds with the actual history of the present. After laying out the feudal heritage which characterizes the mind and culture of the South in the opening chapter, Weaver by turns examines the antebellum and postbellum defense of the Southern way of life, the perspectives of Confederate soldiers and the reminiscences of others during the Civil War (or “the second American Revolution”), the work of selected Southern fiction writers, and then the reformers or internal critics who, in Weaver’s view, effectively managed to take the fight out of the “fighting South.”[28]

Weaver concedes by the end that “the Old South may indeed be a hall hung with splendid tapestries in which no one would care to live; but from them we can learn something of how to live.”[29] It is a disturbing and prophetic line, suggestive of how much the Southern heritage might be abstracted, idealized, and then transferred to distant places and times. Comparing his own situation to that of a Henry Adams, who, “wearied with the plausibilites of his day, looked for some higher reality in the thirteenth-century synthesis of art and faith,” Weaver imagines that the old Confederacy, with its feudal hierarchies and chivalric cultural values, may yet become a model for the social formations to come. Calling the Old South “the last non-materialist civilization in the Western world,” Weaver concludes:

It is this refuge of sentiments and values, of spiritual congeniality, of belief in the word, of reverence for symbolism, whose existence haunts the nation. It is damned for its virtues and praised for its faults, and there are those who wish its annihilation. But most revealing of all is the fear that it gestates the revolutionary impulse of our future.[30]

Behind this elevated rhetoric lies the hoary old dream, indistinct threat, and rebel yell: the South will rise again!

The title of The Southern Tradition at Bay is provocatively descriptive. Since its purview is the period of American history between 1865 and 1910, following the crushing defeat of the former Confederacy and the disastrous period of Reconstruction—not to mention advances in science, the rise of a more industrial mode of production, and the emergence of modernism in the arts and culture—the study’s elaboration of a cognizable “Southern Tradition” rooted in unreconstructed agrarianism and adherence to the ideals of the old Confederacy is intended to establish it as a preferred counter-tradition to that of the victorious North and to the united States in general. Moreover, the phrase “at bay” is suggestive not of defeat or conquest, but of temporary inconvenience; it refers especially to being momentarily held up, kept at a distance, but by no means out of the game. Such an accomplished rhetor as Weaver would no doubt be aware that the phrase derives from the French abayer, “to bark,” and that it probably referred to dogs that were prevented from approaching further to attack and that were thus relegated to merely barking at their prey. (The image of a group of Southerners barking at an uncomprehending North may be all too appropriate when revisiting I’ll Take My Stand, come to think of it.) In other words, The Southern Tradition at Bay’s title nicely encapsulates two powerful aspects of its argument: that the Southern Tradition exists, present tense, long after its ancien régime was disrupted by war and by modernization; and that it was not ever defeated, much less destroyed, but merely kept in abeyance from the then dominant, though less creditable national culture. Weaver’s vision of the South does not imagine a residual or emergent social formation, to mention Raymond Williams’s well-known formulation,[31] but rather another dominant, yet somehow suppressed or isolated, form which remained in constant tension with the only apparently victorious North. Weaver’s mood is sometimes melancholy, befitting his sense of the “lost cause,” but his conviction that the South ought to rise again, whether he believed it was practically feasible or not, is clear throughout.

Thus, the idea of a distinctively Southern tradition being temporarily held “at bay” suits Weaver’s argument well. However, this was not the original title of the study. When he presented it as his doctoral dissertation at Louisiana State University, where his thesis advisor was Cleanth Brooks,[32] Weaver gave it a much more provocative and politically charged title: “The Confederate South, 1865–1910: A Study in the Survival of a Mind and Culture.” The difference is not particularly subtle. Here it is asserted that the “Confederate South,” not just a tradition, itself exists outside of the more limited lifespan of the C.S.A., and that its mind and culture—not merely those of a South, a recognizable section of the United States, but those of the Confederacy—survived the aftermath of the Civil War, a conflict which Weaver dutifully names the “second American Revolution.”[33] Weaver submitted the manuscript to the University of North Carolina Press in 1943, but it was summarily rejected. I have found no evidence one way or another, but I like to think that the publishing arm of the university presided over by Frank Porter Graham declined to publish the execrable apologia of the Confederacy’s “survival,” with its idyllic portrait of human bondage and of racial bigotry, on not only academic but also political grounds. The story is probably less interesting than that, for although the book makes a passionate case for a certain worldview, the dissertation’s extremely selective portrayal of the postbellum culture of the south almost certainly rendered its conclusions dubious from the perspective of academic historians and philosophers. Most likely, Weaver’s omissions, as well as his renunciation of any sense of objectivity or nonpartisanship, led to the study’s remaining unpublished during his lifetime. In any case, its eventual publication in 1968, a transformative moment in U.S. politics and society, makes for a rather intriguing, if unhappy, coincidence. The “Southern strategy,” conceived by Harry Dent and launched by the Nixon campaign that very year, had in The Southern Tradition at Bay its historico-philosophical touchstone.

V

It is all too noteworthy that the “mind and culture” that Weaver identifies as surviving in the aftermath of the Civil War is, at once, generalized so as to extend to the entirety of the American South and limited to a fairly tiny slice of that section’s actual population. Weaver makes no bones about the fact the he wanted to consider only the elite members of that society as representative of this tradition. Asserting that “it is a demonstrable fact that the group in power speaks for the country,” Weaver unapologetically writes that, “[i]n assaying the Southern tradition, therefore, I have taken the spirit which dominated,” thus ignoring Southern abolition societies, for example.[34] He also ignores the majority of the people. In order to make his case, Weaver pays little attention to white people who are not aristocratic lords of their own fiefdoms or soldiers who fought in the Civil War, which is to say, Weaver largely overlooks the poor multitudes who vastly outnumbered the wealthy planters, military leaders, and governors. Also, though not unexpectedly, the black population, a not inconsiderable percentage of the populace in these states, is treated far worse, in this account; black Southerners are not ignored, but rather are called out for special treatment in assessing their significant role in making possible the this culture and its tradition.[35]

Indeed, Weaver refers to blacks in the South as “the alien race,” as if he cannot understand that persons of African descent are no more or less alien to the lands of the Americas than are those of European descent. “Alien” cannot here mean “foreign,” since Weaver highlights the Southerner’s kinship to the Europeans, whether genealogically or with respect to social values. Weaver almost blames the black servants for being “inferior,” the mere fact of which itself could lead to abuse and therefore can reflect badly on the moral constitution of the white superiors. For example, after praising the idyllic state of paternalism in which “[t]he master expected of his servants loyalty; the servants of the master interest and protection,” and going so far to note that even at present, “so many years after emancipation,” the Southern plantation owner will routinely “defray the medical expenses of his Negroes” and “get them out of jail when they have been committed for minor offenses,” Weaver concedes that

This is the spirit of feudalism in its optative aspect; some abuses were inevitable, and in the South lordship over an alien and primitive race had less favorable effects upon the character of the slaveowners. It made them arrogant and impatient, and it filled them with boundless self-assurance. Even the children, noting the deference paid to their elders by the servants, began at an early age to take on airs of command. […] These traits [i.e., irritability, impatience, vengefulness], which were almost invariably noted by Northerners and by visiting Englishmen, gave Southerners a reputation away from home which they thought baseless and inspired by malice.[36]

Weaver never doubts whether the feudal paternalism of the plantation owner, pre- or post-emancipation, to “his Negroes” would have appeared quite so optative in its aspect to the servants themselves. Informed readers, regardless of their own political views, cannot help but question this formulation.

In Weaver’s view, all servants—almost exclusively understood to be members of an “alien race” as well as being a subaltern class—on a Southern plantation are either happy and loyal or hopelessly deluded. During the Civil War, for example, “the alien race, which numbered about four millions in the South, kept its accustomed place, excepting those who through contact with the Federal armies were won away from adherence to ‘massa’ and ‘ol’ mistis’.”[37] This appears in a section called “The Negroes in Transition,” within a long chapter titled “Diaries and Reminiscences of the Second American Revolution,” and Weaver’s unmistakable conclusion is that the black population of the South was almost entirely better off under the system of slavery. Indeed, from his blinkered perspective, the African Americans under consideration would be better off as slaves precisely because they are more naturally suited to that condition. This position constitutes not merely an apologia of human bondage but also a casual acceptance of the most foul racial bigotry. Weaver cannot seem to imagine a reasonable reader who would question white supremacy, which he and the authorities he approvingly cites take to be a matter of fact. “The Northern conception that the Negro was merely a sunburned white man, ‘whose only crime was the color of his skin,’ found no converts at all among the people who had lived and worked with him.”[38] Weaver thus intimates that those, such as the Northerners, who believed otherwise were merely ignorant of the facts familiar to any and all with the least bit of experiential knowledge. Similarly, when Weaver writes that “[m]ore than one writer took the view that it was impossible for the two races to dwell together unless the blacks remained in a condition approximating slavery,” he offers not a word to gainsay the view, and he tacitly endorses it throughout the book.[39]

Weaver’s somewhat disingenuous assertion that he is “letting the contemporaries speak” for themselves is hardly an excuse for this profoundly racist account. Even if he relied only on direct quotations, which he certainly does not, Weaver had already conceded that he was rather selective in how he would approach his project. Needless to say, perhaps, but “The Negroes in Transition” section makes no reference whatsoever to any black authorities; in fact, Weaver here seems to rely entirely on the remembrances of Southern belles, as the footnotes in this section refer exclusively to autobiographies or memoirs written by white women, including one titled A Belle of the Fifties.[40] (The suggestion that free blacks represented a threat to white women is not so subtly hinted at in the pages.) Weaver quotes liberally from the women’s writings, but he frequently editorializes and supplements their mostly first-person perceptions with an almost scientific assessment, expounding on the laws governing society and nature.[41] For example, having just mentioned both slavery and race, and therefore leaving no doubt in the mind of the readers as to the racial criteria by which a social hierarchy of the type he is endorsing would be established, Weaver asserts: “[o]ut of the natural reverence for intellect and virtue there arises an impulse to segregation, which broadly results in coarser natures, that is, those of duller mental and moral sensibility, being lodged at the bottom and those of more refined at the top.”[42] Indeed, Weaver goes so far as to credit the endemic racism of the Southerner with a kind of moral superiority over those who lack this good sense. He argues that, in the Southerner’s “endeavor to grade men by their moral and intellectual worth,” his defense of slavery and racial hierarchy “indicates an ethical awareness” missing from many Northerners’ perspectives.[43]

That politics in the United States has, since 1968, become increasingly characterized by racial division is both controversial and indubitable. The “post-racial” America presided over by Barack Obama has witnessed some of the most acrimonious, racially-inflected public discourse and debate in years. Yet open appeals to racial justice or to discriminatory practices are considered gauche. As I mentioned at the beginning of this essay, a form of “dog-whistle politics” has infiltrated nearly all political rhetoric in recent decades. Perhaps the most infamous example of this “dog-whistle” political strategy can be found in Lee Atwater’s remarkably candid revelation in a 1981 interview. The former Strom Thurmond acolyte, who later served in the Reagan White House, then as George H. W. Bush’s 1988 campaign manager, and who later became chairman of the Republican National Committee, Atwater is acknowledged as one of the most astute political strategists of his generation. In speaking (anonymously, at the time) of the Reagan campaign’s far more elegant and effective version of the Southern strategy, Atwater explained:

You start out in 1954 by saying, “Nigger, nigger, nigger.” By 1968, you can’t say “nigger”—that hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like forced busing, states’ rights and all that stuff. You’re getting so abstract now [that] you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is [that] blacks get hurt worse than whites. And subconsciously maybe that is part of it. I’m not saying that. But I’m saying that if it is getting that abstract, and that coded, that we are doing away with the racial problem one way or the other. You follow me—because obviously sitting around saying, “We want to cut this,” is much more abstract than even the busing thing, and a hell of a lot more abstract than Nigger, nigger.”[44]

The fact that abstract economic issues, which presumably would affect both whites and blacks in the relatively poor Southern states in more-or-less equal measure, are so effective as code words for traditional, race-baiting tactics of a previous generation—the era of Willis Smith, in fact—demonstrates the degree to which Weaver’s feudal hierarchies maintain themselves, now in an utterly fantastic way as a vague threat, well into the late twentieth century or early twenty-first. As Atwater suggested, Southern white voters are willing to endorse policies that actually harm them, so long as a byproduct of those policies is that “blacks get hurt worse than whites.” This too, it seems, has much to do with the survival of a mind and culture in the aftermath of slavery and war, and so it is not altogether surprising that Weaver’s examination of the Southern tradition “at bay” focuses so intently on demonstrating why the black population of the South ought to remain subjugated to the white population as the era of civil rights, desegregation, and modernization dawns on the region.[45]

VI

In his appreciative remembrance of I’ll Take My Stand, written on the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary of its publication, Weaver invoked the image of the “Southern Phoenix,” a mythic reference to a being that had regenerated itself from the ashes following its own fiery destruction. Weaver uses this figure not so much to recall how the Agrarians whose work constituted that epochal text had themselves gone on to greatness, even if the volume had been ridiculed and dismissed by Northern critics in the 1930s. Weaver is also thinking of the tenets and values of the Old South, those that the Vanderbilt Fugitives and Agrarians embraced and promoted, which must have seemed retrograde, even malignant to so many in 1930, but which had reemerged and flourished amid an ascendant conservatism just beginning to take shape nationally in 1960. Yet, for all its usefulness as a metaphor, the phoenix is probably also an apt figure for Weaver’s own conservative vision, since—like an imaginary creature taken from the provinces of mythology—Weaver’s image of the Southern tradition, whether at bay or on the offensive, is profoundly fantastic. This imaginary tradition is rooted in a world that almost certainly never existed, not on a wide scale at any rate, and the polemical forces of Weaver’s argument are directed at a foe that has been conceived as an immense Leviathan, but which we today know to have been largely chimerical.

At times, this argument becomes almost comical. In explaining the importance of “the last metaphysical right,” private property, for example, Weaver cites the example of Thoreau,[46] although the latter’s notorious experiment in living deliberately required him to purchase, not build, a prefabricated hut, then to place it and himself on property owned by another (Emerson, in fact), but which he was permitted to dwell upon rent-free. Far from demonstrating the self-sufficiency and resolve of the individual, Thoreau’s experiment might be taken as exemplary of a kind of localized welfare system; one need not punch the clock at the local factory if one lives off the generosity and largess of family and friends. However, as we have seen increasingly in the United States in recent years, the receipt of corporate and other forms of welfare in no way prevents the recipients from bashing the government for offering support to others. The Republican Party’s adoption of the “We Built It” slogan in 2012 offers a tellingly Thoreauvian fantasy, one where it is possible to accept the public’s funding while insisting upon absolute independence from the commonweal.

Given the importance of a sense of place and of community to Weaver’s fantastic vision of a medieval heritage, such rampant individualism—an ideology subtending the basic neoliberal projection of free markets and autonomous economic actors—seems quite foreign. Indeed, it is odd to talk about Weaver as a forebear to contemporary conservatism. Certainly the economic neoliberalism which celebrates unfettered free markets and the geopolitical neoconservatism which glories in globalization and preemptive military engagements are a far cry from Weaver’s fanciful nostalgia for an idealistic feudalism founded upon rigid social hierarchies, chivalric codes of ethics, and a powerful, culture-shaping religion or religiosity.[47] In his own writings, we can see Weaver’s strong aversion to the emergent globalization and even nationalization, which he views as corrupting the properly regionalist values he favored. Weaver’s worldview would not have allowed him to embrace the preemptive war strategies championed by Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld, and Paul Wolfowitz during the various military conflicts of the past 30 years. Moreover, Weaver’s ardent defense of the humanities—recall his loathing for the educational and cultural aura of Texas A&M, now home to the George [H. W.] Bush Presidential Library—is entirely at odds with the views on higher education, the arts, philosophy, and “high” culture held by the most prominent and visible members of the G.O.P. today. Yet, the sectarianism of Weaver’s view paved the way for contemporary neoconservative politics and policies. Weaver’s well-nigh Schmittian, Us-versus-Them antagonism, requires us to envision not merely a Western civilization opposed to its non-western rivals but a truer, more valuable “Southern” civilization against the putatively uncivilized rest of the United States. The loathsome, omnipresent discourse about “real” Americans and what constitutes them is a legacy of the Southern Agrarian traditions apotheosized by Weaver’s philosophy.

Indeed, the particular labels—conservative, neoconservative, neoliberal, and so forth—are not necessarily helpful in understanding the dominant political and cultural discourses in the United States in the twenty-first century. As Paul A. Bové has observed, “[m]any critics of the Far Right movement conservatism mischaracterize it. It is not an epiphenomenon of neoliberalism. In fact, the popular elements of this movement, of its electoral coalition, resent the economic and cultural consequences of neoliberalism and globalization in politics and culture.”[48] To many of the policies and even most of the ideas of the neoconservatives like Wolfowitz, Cheney, and both Presidents Bush, Weaver and his beloved Agrarians would almost certainly object. However, the cultural and intellectual foundations of the neoconservatives’ positions, not to mention the fact of their being elected or appointed to offices of great power in the first place, owes much to an ideological transformation of U.S. intellectual culture whose fons et origo may be found in the fantastic vision of a distinctively Southern exceptionalism.

One might well name this the australization of American politics, as the Southern section’s purportedly unique culture has tended, since the 1960s, to be more and more representative of a national conservative movement. This movement, which has become perhaps the most influential force within the Republican Party at a moment when the conservative politics has itself become more prominent in the United States, thus tends to be the dominant force in national, and increasingly international, politics as well. It should not be forgotten that the rightward shift even in the Democratic Party can itself be linked to this increasingly australized politics, as both Georgia’s Jimmy Carter and Arkansas’s Bill Clinton emerged nationally as the preferable, because more conservative, candidates who would stand up to the old-fashioned liberals in their own party (inevitably symbolized by Ted Kennedy, Mario Cuomo, or Jesse Jackson).[49] In their commitment to economic growth, particularly that made possible by increasingly corporate or industrial development, these conservative Southern Democrats would have earned the agrarian-minded Weaver’s contempt, but their rhetorical and ideological commitments align far better with the agrarian discourse than did the expansive liberalism of the New Deal or the Great Society. Weaver would undoubtedly decry the rapid growth of the South’s population in recent decades, since that growth has been generated in large part by ever more industrial or urban development, but he would probably delight in seeing the rust of the Rust Belt as unionization, heavy industry, and traditional urbanism has declined in the North and Northeast. The shifting numbers of electoral votes in favor of Southern states is also a real consideration for any political or cultural program interested in preserving or expanding Southern “values” in the United States. The fall of the hated North, in this view, is almost as sweet as the South’s rising again.

The costs of this australization of American politics are incalculable, as may be inferred from the increasingly vicious public discourse with respect to all manner of things, including welfare and taxation, education, science, the environment, individual rights, foreign adventures, war, domestic surveillance (a form of paternalism), and so forth. As far back as 1941, W. J. Cash had concluded his study of The Mind of the South by noting the “characteristic vices” of that culture:

Violence, intolerance, aversion and suspicion toward new ideas, an incapacity for analysis, an inclination to act from feeling rather than from thought, an exaggerated individualism and too narrow concept of social responsibility, attachment to fictions and false values, above all too great attachment to racial values and a tendency to justify cruelty and injustice in the name of those values, sentimentality and a lack of realism—these have been its characteristic vices in the past. And, despite changes for the better, they remain its characteristic vices today.[50]

Taken out of their original context, these words seem all too timely in the twenty-first century, with the events of Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014 or Baltimore, Maryland, in 2015, among many other less spectacular and more pervasive examples, resounding throughout the body politic. In Cash’s final lines, he abjured any temptation to play the role of prophet, declaring that it would be “a brave man” who would venture definite prophecies, and it would be “a madman who would venture them in the face of the forces sweeping over the world in 1940.”[51] Bravery or madness notwithstanding, Cash likely could not have imagined the degree to which the characteristic vices of the South in his time could become so widespread to have become the characteristics of a national American “mind” tout court in the next century.

Moreover, as should be obvious, the australization of American politics is not simply a matter of political leaders or voters residing in the southern parts of the United States. The pervasiveness of a certain identifiably Southern cultural signifiers within mainstream political discourse, particularly in the more conservative members of the Republican Party but also throughout the public policy and electioneering rhetoric of both major parties, signals a victory for that fantastic or idealistic “mind and culture” so celebrated by Weaver and his Agrarian forebears. It is a terrifying prospect for many, but the vision of the intransigent Southern traditionalist now operating from a position of broad-based cultural and political power on a national, indeed an international, stage might be the apotheosis of Weaver’s grand historical investigation into the region’s purportedly distinctive past. As Weaver put it in a 1957 essay,

It may be that after a long period of trouble and hardship, brought on in my opinion by being more sinned against than sinning, this unyielding Southerner will emerge as a providential instrument for saving this nation. […] If that time should come, the nation as a whole would understand the spirit that marched with Lee and Jackson and charged with Pickett.[52]

For most people residing in the United States, including many of us in the South (like me, some of whose ancestors did march with these men in the early 1860s), the prospect of a neo-Confederate savior of the nation or world is horrifying, like a mythological monster assuming worldly power. Sifting through the ashes of the triumphant Southern Phoenix, we are likely to find much of value has been destroyed.

Notes

[1] Quoted in Julian M. Pleasants and Augustus M. Burns III, Frank Porter Graham and the 1950 Senate Race in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press), 183. On the term “dog-whistle politics,” see Ian Haney López, Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism and Wrecked the Middle Class (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[2] Richard M. Weaver, “Agrarianism in Exile,” in The Southern Essays of Richard M. Weaver, ed. George M. Curtis III and James J. Thompson Jr. (Indianapolis: Liberty Press, 1987), 40, 44.

[3] Weaver, “The Southern Phoenix,” in The Southern Essays of Richard M. Weaver, 17.

[4] See Paul A. Bové, “Agriculture and Academe: America’s Southern Question,” in Mastering Discourse: The Politics of Intellectual Culture (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991), 113–142.

[5] Recent events concerning the removal of the “Confederate Flag,” the notorious symbol of racism wielded by the KKK and others, from state capitols and other official sites in the South appears to be a surprising turn of events, although cynics could argue that, in turning attention away for gun violence and particularly violence against black citizens and other minorities, the flag issue has provided a convenient cover, allowing the media to ignore more urgent social problems in the wake of the Charleston massacre. Still, symbols are powerful, and the removal of this symbol is itself a hopeful sign as even conservative politicians and pundit have realized, all too late, what the embrace of the lost Confederacy has cost them on a moral level. See, e.g., Russ Douthat, “For the South, Against the Confederacy,” New York Times blog (June 24, 2015): http://douthat.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/06/24/for-the-south-against-the-confederacy/?_r=0.

[6] Donald Davidson, “The Vision of Richard Weaver: A Foreword,” in Richard M. Weaver, The Southern Tradition at Bay: A History of Postbellum Thought, eds. George Core and M. E. Bradford (New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1968), 17.

[7] Weaver, “Up from Liberalism” [1958–59], in The Vision of Richard Weaver, ed. Joseph Scotchie (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1995), 20.

[8] See Fred Douglas Young, Richard M. Weaver, 1910–1963: A Life of the Mind (Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 1995), 56 –58.

[9] Weaver, “Up from Liberalism,” 23.

[10] Ibid., 28.

[11] Joseph Scotchie, “Introduction: From Weaverville to Posterity,” in The Vision of Richard Weaver, 9–10.

[12] Ibid., 9.

[13] Weaver, “Up from Liberalism,” 31. Notwithstanding the use of the word “holocaust,” Weaver makes no mention of the Nazis or the concentration camps in this essay; rather, his example is “the abandonment of Finland by Britain and the United States” (31).

[14] Weaver, Ideas Have Consequences (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1948), 2–3.

[15] See Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment, trans. John Cumming (New York: Continuum, 1987), 3. See also Adorno, The Jargon of Authenticity, trans. Knut Tarnowski and Frederic Will (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1973).

[16] Weaver, Ideas Have Consequences, 129.

[17] Weaver, “On Setting the Clock Right,” In Defense of Tradition: Collected Shorter Writings of Richard M. Weaver, ed. Ted J. Smith III (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2000), 559–566.

[18] Weaver, Ideas Have Consequences, 131.

[19] Ibid., 132.

[20] Ibid., 148.

[21] Ibid., 172.

[22] Ibid., 187.

[23] In a later essay, Weaver compares the difference between the American North and the South to that between the United States and England, France, or China. In the same essay, Weaver adds that “The South […] still looks among a man’s credentials for where he’s from, and not all places, even in the South, are equal. Before a Virginian, a North Carolinian is supposed to stand cap in hand. And faced with the hauteur of an old family from Charleston, South Carolina, even a Virginian may shuffle his feet and look uneasy.” See “The Southern Tradition,” in The Southern Essays of Richard M. Weaver, 210, 225.

[24] Cervantes, Don Quixote, trans. J. M. Cohen (New York: Penguin, 1950), 149. Apparently, many conservatives would not object to such a comparison. For example, in his history on the right-wing Intercollegiate Studies Institute, Lee Edwards approvingly begins by saying of its founder, “Frank Chodorov had been tilting against windmills all his life.” See Edwards, Educating for Liberty: The First Half-Century of the Intercollegiate Studies Institute (Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, 2003), 1.

[25] At no point does Weaver cite Cash’s The Mind of the South (originally published in 1941), which in this context must be seen as a sort of “absent presence” for Weaver and others who carried the torch for the Agrarians in the 1940s and beyond. The Mind of the South appeared while Weaver was working on his dissertation, and Weaver’s own study might even be seen as a tactical critique of, or at least alterative to, Cash’s celebrated work. See W. J. Cash, The Mind of the South (New York: Vintage, 1991). Although these two native North Carolinian authors identify some of the same characteristics and even arrive at similar conclusions about the “mind of the South,” they also maintain rather different social and political positions. For one thing, Cash does not see a feudal or aristocratic Southern character as praiseworthy, whereas Weaver’s entire defense of the Southern tradition rests on his admiration for and allegiance toward the aristocratic virtues of the archetypal Southerner.

[26] Weaver, The Southern Tradition at Bay, 44.

[27] One legitimate critique of Cash’s The Mind of the South was that it focused primarily on the attitudes and customary habits associated with Cash’s own Piedmont region of North Carolina (which happens to be my native region as well), thus underestimating the divergences to be found in the Tidewater zones to the east or the “Deep South” below and to the west. Weaver’s Southern Tradition at Bay does not limit its approach by regions, giving more or less equal space to views from all parts of the South, but it does severely restrict itself to materials best suited to make its argument with respect to a feudal system. Hence, Weaver tends to ignore the experiences of those who did not live on large estates or plantations, which is to say, Weaver omits the experiences of the vast majority of Southerners. If Cash’s study could be faulted for its Mencken-esque journalistic techniques—Cash’s original article, “The Mind of the South,” did appear in H. L. Mencken’s American Mercury, after all—and its lack of intellectual rigor, Weaver’s more academic study (it was a PhD dissertation, of course), in its questionable method and especially in its selectivity, also raises doubts about the “mind” it purports to lay bare.

[28] Weaver, The Southern Tradition at Bay, 387.

[29] Ibid., 396.

[30] Ibid., 391.

[31] See Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977), 121–127.

[32] Weaver’s advisor had been the cultural historian, literary critic, and biographer Arlin Turner, but Brooks stepped in only near the end to serve as the head of Weaver’s thesis committee. In his biography, Young reports that “Weaver was in the final stages of writing his dissertation when Turner left LSU to take a position at Duke University; Cleanth Brooks became his advisor at that point and oversaw the work to its conclusion” (78). However, as far as I can tell, Turner did not arrive at Duke until 1953, ten years after Weaver received his Ph.D. degree. The more likely reason for the change in advisor, as Fred Douglas Young writes, was that Turner was “called up for service in the U.S. Navy,” which is why Weaver asked Brooks to serve as dissertation director at the last minute (see Young, Richard M. Weaver, 67). I am not prepared to speculate on the relationship between teacher and student, but I might note that Turner, a native Texan who wrote a well-regarded biography of Nathaniel Hawthorne and later became the editor of American Literature, likely did not share his former student’s strictly sectarian views with respect to the opposed and irreconcilable cultures of the North and the South.

[33] See Weaver, The Southern Tradition at Bay, 41, 231–275.

[34] Ibid., 30.

[35] Although it lies well outside the scope of the present essay, it would be interesting to consider the other side of Weaver’s celebratory medievalism by looking a Eugene D. Genovese’s Roll Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (New York: Random House, 1974). Genovese also identifies a patriarchal, paternalistic society in which religion or religiosity played a crucial role, but he focuses attention on the essential contributions of the slaves in forming this distinctively Southern culture. Genovese, then a Marxist historian influenced by Gramsci, among others, later became a notoriously conservative thinker in his own right, a shift that coincided—perhaps not coincidentally?—with his growing interest in the Agrarians of the I’ll Take My Stand era, which culminated in a book whose title could have come directly from Weaver’s own pen: see Genovese, The Southern Tradition: The Achievement and Limitations of an American Conservatism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994).

[36] Ibid., 55–57.

[37] Ibid., 259. Being “won away” is, for Weaver, a sign of the servant’s delusion. Indeed, this line follows directly from a section which concluded that “the blacks suffered as much maltreatment as the whites, the [Union] soldiery being as ready to snatch the silver watch of the slave as the gold one of his master” (258).

[38] Ibid., 261.

[39] Ibid., 173. Weaver lists a number of postbellum incidents, including “disturbing reports of Negro voodooism,” as evidence that Southern blacks, now lacking the beneficial effects of a civilizing servitude, would “soon relapse into savagery” (261–262).

[40] Incidentally, Weaver’s overall assessment of women’s rights is not much more salutary than his position on civil rights for persons of color, at least with respect to the decline of the West. In Ideas Have Consequences, Weaver laments that, although “[w]omen would seem to be the natural ally in any campaign to reverse” the anti-chivalric modern trends that have rendered Western civilization so spiritually vacant, in fact, they have not. “After the gentlemen went, the lady had to go too. No longer protected, the woman now has her career, in which she makes a drab pilgrimage from two-room apartment to job to divorce court” (180). Without chivalry, Weaver concludes, there can be no ladies.

[41] See The Southern Tradition at Bay, 268.

[42] Ibid., 36–37.

[43] Ibid., 35.

[44] Quoted in Alexander P. Lamis, “The Two-Party South: From the 1960s to the 1990s,” in Southern Politics in the 1990s, ed. Alexander P. Lamis (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1999), 8.

[45] Contrast this view with the lament by which Albert D. Kirwan chooses to conclude his near-contemporaneous, 1951 study of postbellum Mississippi politics: “As for the Negro, whose presence in such large numbers in Mississippi has given such a distinctive influence to its politics, his lot did not change throughout this period. No one thought of him save to hold him down. No one sought to improve him. […] He was and is the neglected man in Mississippi, though not the forgotten man.” See Kirwan, The Revolt of the Rednecks: Mississippi Politics, 1875–1925 (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1964), 314.

[46] Weaver, Ideas Have Consequences, 132. Thoreau seems to be the one Yankee whom Weaver is willing to consider a non-barbarian. See also The Southern Tradition at Bay, 41: “Southerners apply the term ‘Yankee’ as the Greeks did ‘barbarian.’ The kinship of ideas cannot be overlooked.”

[47] Space does not permit a full consideration of the matter, but Weaver’s embrace of a certain Southern “non-creedal religiosity” would not necessarily seem to fit easily with the rise of the religious right in the 1980s and beyond, particularly when considering the prominence of certain denominations and organization, like the Southern Baptist Convention, in political and cultural debates of recent decades. However, one might also recognize the apparently Southern accent with which must of the new political religiosity has been voiced on a national level, which suggests another aspect of the australization of American politics.

[48] Paul A. Bové, A More Conservative Place: Intellectual Culture in the Bush Era (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press, 2013), 10.

[49] Bill Clinton, then Governor of Arkansas, made his name nationally as the Chairman of the Democratic Leadership Council, an organization founded in the aftermath of the 1984 Reagan re-election landslide. The D.L.C. was established the express aim of promoting more conservative policies within the Party and nationally, and its leadership largely consisted of Southerners, not coincidentally.

[50] Cash, The Mind of the South, 428–429.

[51] Ibid., 429.

[52] Weaver, “The South and the American Union,” in The Southern Essays of Richard M. Weaver, 256.