by Brian Meeks

This essay has been peer-reviewed by the b2o editorial collective. It is part of a dossier on Stuart Hall.

A Lost Moment

There is an intriguing quote in Kuan-Hsing Chen’s 1996 interview with Stuart Hall, in which Stuart, in response to Chen’s question/comment “But you never tried to exercise your intellectual power back home”, responds:

There have been moments when I have intervened in my home parts. At a certain point, before 1968, I was engaged with dialogue with the people I knew in that generation, principally to try to resolve the difference between a black Marxist grouping and a black nationalist tendency. I said, you ought to be talking to one another. The black Marxists were looking for the Jamaican proletariat, but there were no heavy industries in Jamaica; and they were not listening to the cultural revolutionary thrust of the black nationalists and Rastafarians, who were developing a more persuasive cultural, or subjective language. But essentially, I never tried to play a major political role there. (Morley and Chen 1996:501-2; see also MacCabe 2008:17)

He explains this through his recognition that he had found both a personal space – marriage to Catherine – and a political space, as a collaborator in the British New Left and that Jamaica herself, in the transition to independence, had become a somewhat different society, breaking with the past, making it somewhat easier for him to leave and that these were coincident with the domestic and political changes in his own life.

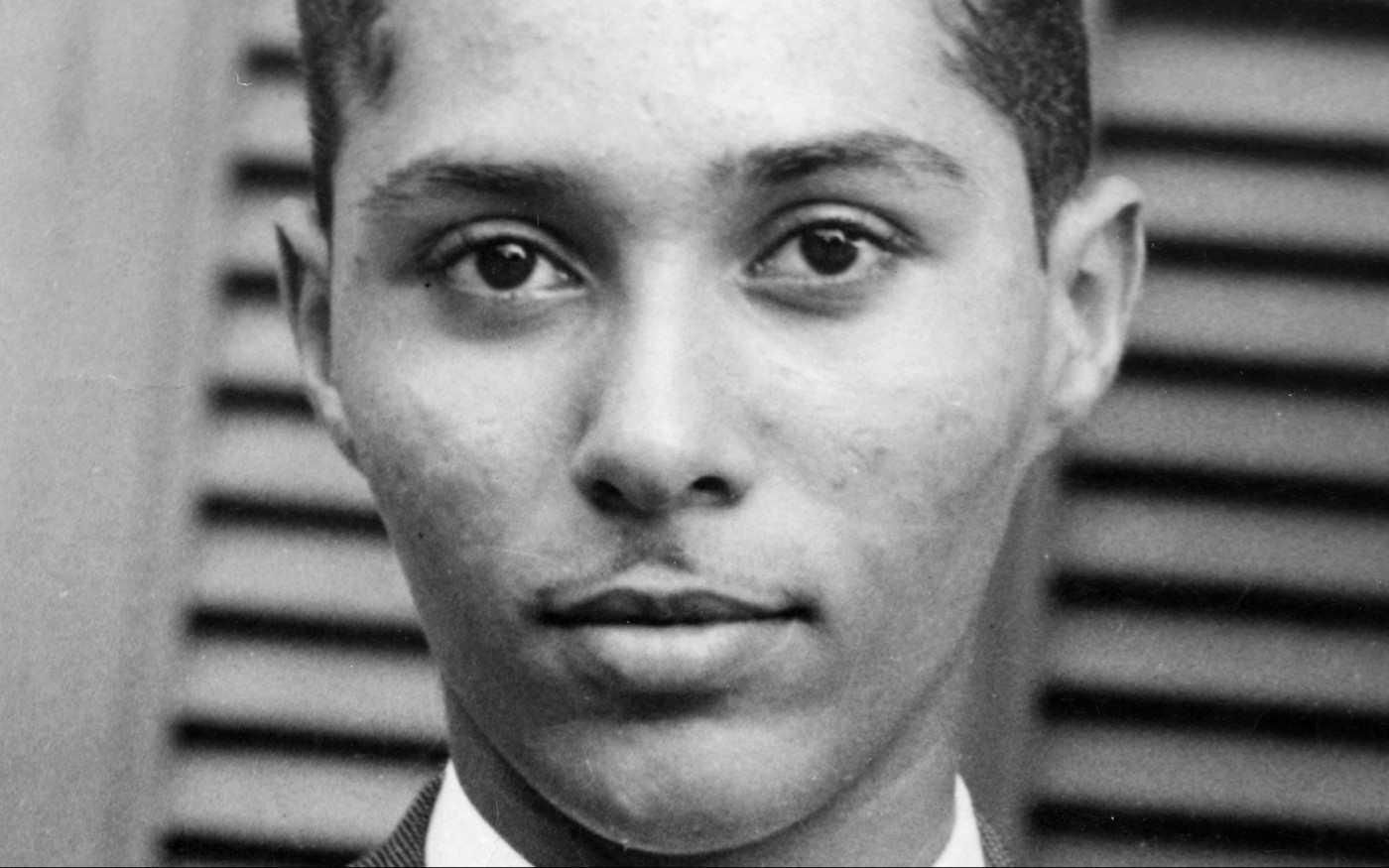

This conscious sense of not seeking to intervene in a changed political space with which he no longer felt intimately familiar was captured when both Tony Bogues (Bogues 2015: 177-193) and I met with Stuart separately in 2003 to encourage him to attend the Centre for Caribbean Thought’s conference that we were planning in his honor the following year. His response to both of us was that, yes, he was born in Jamaica, but it would be difficult to describe himself as a ‘Caribbean intellectual’ and therefore, was it appropriate to include him in a series of conferences honoring key contributors to Caribbean thought? In the end we managed to convince him to attend and that being from the Caribbean and with much of his critical formation occurring here, he was very much a Caribbean intellectual. The 2004 conference turned out to be a remarkable event (see Meeks 2007) in which Hall ‘came home’ and found, as it were, not only his Jamaican and Caribbean audience, but that there was already some younger scholars who were drawn to his work. On balance though, beyond the cognoscenti, Hall’s work was in the period after 1968 to which he referred – the period of the popular upsurge of radical politics in the region – right up until the moment of our conference, still largely unknown. I knew of Stuart as a brilliant Jamaican because he had been my Dad’s classmate at Jamaica College and as one of the School’s Rhodes Scholars, I recognized his name inscribed along with that of Norman Manley and others on the long blackboards outside the neo-gothic Simms building at school. But it was not until the mid-Eighties that I had heard anything about his work and I read my first Hall article long after finishing my PhD thesis in 1988.

Thus, aside from the tantalizing intervention quoted above, his name and more so his thinking, were largely unknown to the generation of Sixty-Eight, those who were tossed into politics after the infamous exclusion of Walter Rodney on his return home to Kingston from the 1968 Montreal Congress of Black Writers (see Austin 2013:22). The intense, one-day Black Power riots which followed the police tear-gassing of the student protest in support of Rodney, signaled the beginning of a decade and a half process of radicalization which led to the 1970 ‘Black Power Revolution’ in Trinidad and Tobago, the election of the Michael Manley government in Jamaica in 1972 and the Grenada Revolution of 1979-1983. (See Ryan and Stewart 1995; Quinn 2014)

The Generation of Sixty-Eight

Another famous Anglo-Caribbean expatriate thinker of the Left – C.L.R. James – was certainly better known and influenced a generation of Caribbean scholars, (Meeks and Girvan 2010:4) but in terms of a substantial impact on the theoretical orientation, form, strategy and tactics of the burgeoning movement, Jamesian ideas were, at best, marginal.[1] (Mars 1998:31-61) There was the Antigua Caribbean Liberation Movement (ACLM) in Antigua, under the leadership of the Jamesian Tim Hector and the Working People’s Alliance (WPA) in Guyana, where Rodney himself, before his assassination (in 1980), Rupert Roopnarine, Eusi Kwayana and others, sought to build a more independent left. Other Jamesian tendencies included the Revolutionary Marxist Collective (RMC) in Jamaica, the New Beginning Movement (NBM) in Trinidad and the Movement for Assemblies of the People (MAP) in Grenada. Only MAP would emerge to play a central role in the evolving political landscape, but only after its merger with JEWEL (Joint Endeavour for Welfare, Education and Liberation) to form the Marxist-Leninist New Jewel Movement (NJM), later to become the vanguard party of the Grenadian Revolution.

Thus, by the mid-Seventies, most of the independent, radical trends had either been eclipsed by or converted to one or another variant of what I refer to here as ‘Caribbean Marxism-Leninism’. I use this notion in order both to avoid a simplistic reductionism of compressing all Marxist trends and simultaneously to tease out and identify the specific characteristics of the parties and movements which came to dominate the Caribbean Left. These parties included the Cheddi Jagan-led People’s Progressive Party (PPP) of Guyana, which had held office and been excluded from power twice by the British, but remained bedeviled by the ethnic question and its partisan rootedness in the East Indian bloc; (see Palmer, 2010) the Movement for National Liberation (MONALI) in Barbados; the Youlou Liberation Movement (YULIMO) in St Vincent; the Workers Revolutionary Movement (WRM) in St Lucia and the Dominica Liberation Movement (DLM). However, the two most significant, aside from the PPP, were the Workers Party of Jamaica (WPJ) and the NJM.

The WPJ, despite dominating what constituted the Jamaican Left outside of Manley’s governing People’s National Party (PNP), failed to gain any significant electoral support in the elections-driven Jamaican political system. It nonetheless accumulated significant influence through its almost hegemonic control over a generation of activist students and scholars at the University of the West Indies Mona campus, its informal linkages to the left in the PNP regime and most importantly and in the end most damagingly, its close connections and influence within the NJM. The NJM for its part, not only became part of the opposition alliance following the 1976 elections, but the leader of the Party, Maurice Bishop became the constitutional Leader of the Opposition. Three years later, with the successful overthrow of the Eric Gairy regime, Bishop would become Prime Minister of the People’s Revolutionary Government (PRG) of Grenada for the next four and a half years. The Grenadian Revolution ended tragically with open divisions surrounding questions of leadership in the Party leading to the October 1983 arrest of Bishop, his release by an incensed crowd of supporters, his attempt to wrest control of the military fort, a clash with the military which remained loyal to the Party and his execution along with some of his closest supporters, at the hands of his own soldiers. (See Meeks 1993; Lewis 1987; Marable 1987; Puri 2011 and Scott 2014)

This tragic and unprecedented end to the Grenadian Revolution which also signaled the demise of an organized and vibrant Caribbean left, has led to heated, often recriminatory interventions seeking to explain and understand how it could have happened. Most analyses, including, I admit, my own, focus more on personalities, leadership, structures and the supporting or denying of purported conspiracies. Thus, Bobby Clarke, not untypically, blames Bernard Coard, Bishop’s Deputy Prime Minister, whom he argues, without further elaboration of this emotive notion and its applicability in this context, had been influenced by the ‘Stalinist’ Trevor Munroe (Meeks 2014:113). In one of the more thoughtful attempts to come to terms with the tragic sequence of events, G.K. Lewis, however, along with recognizing the dangers inherent in military overthrows and ‘the mixture of revolution and armed force’ (Lewis 1987:162) also raises warnings about the danger of mechanically applying Leninist approaches to party organization in entirely different historical contexts to that of Russia in 1917. (167)

It is in the spirit of Lewis’s attempt to understand the theoretical weaknesses and lacunae in the NJM and by implication in Caribbean Marxism-Leninism[2] that I want to proceed with the following hypothetical exercise, by counterpoising critical features of Caribbean Marxism-Leninism with Stuart Hall’s career-long and profoundly humanist engagement with Marxism through the avenue of the conjuncture. I want to suggest that it was precisely a perspective like Hall’s that might have provided an effective counterpoint to the damaging, authoritarian features of Caribbean Marxism-Leninism. An approach like his was missing in Jamaica and this absence contributed to the de facto emergence of particularly wooden and dogmatic theories that came to dominate the Jamaican and other critical components of the Caribbean Left and contributed in no small measure to the tragedy of the Grenada Revolution.

Hall’s Core

I begin by suggesting that unlike positions taken by Rojek and certainly Mills in his critique of Hall’s approach to race (see Rojek 2003; Meeks 2007:120-148) and despite recognizing an evolution, particularly a shift from an earlier more Gramscian inflection to a later, more discursive approach, there is an evident and consistent[3] core to Hall’s oeuvre that includes the following elements:

- Unlike some post-Marxian perspectives, Hall throughout his mature writing continues to place critical importance on capital and of ‘material conditions’ generally, in the shaping of the contemporary world. Thus in his 1988 essay “The Toad in the Garden; Thatcherism Among the Theorists”, while recognizing that there is no “univocal” way in which class interests are expressed, he nonetheless underlines that “…class interest, class position, and material factors are useful, even necessary, starting points in the analysis of any ideological formation.” (Hall 1998: 45) And in his 2007 interview with Colin MacCabe, he reminds him of the importance of the tendencies in capital to concentrate wealth and shape intellectual expression: “…global capitalism is an incredibly dynamic system. And it’s capable of destroying one whole set of industries in order to create another set. Incredible. This is capitalism in its most global, dynamic form, but it is not all that secure. It’s standing on the top of huge debt and financial problems. And I can’t believe those problems won’t come eventually to find their political, critical, countercultural, intellectual expression. We’re just in the bad half of the Kondratiev cycle!” (MacCabe 2008:42)

- Nonetheless, he discounts the mechanical notion of any direct cause and effect relationship between material conditions and so-called superstructural spheres. Social and cultural life, Hall has consistently argued, is not only mediated and articulated away from the ‘forces of production’, but particularly in the contemporary era of intensified media engagement, the internet and the image, this autonomy is even more enhanced. “This approach replaces the notion of fixed ideological meanings and class-ascribed ideologies with the concepts of ideological terrains of struggle and the task of ideological transformation. It is the general movement in this direction, away from an abstract general theory of ideology, and towards the more concrete analysis of how, in particular historical situations, ideas ‘organize human masses, and create the terrain on which men move, acquire consciousness of their position, struggle etc.” (Hall 1996: 41)

- Specifically, in relation to classes and organized systems of domination, he opposes the mechanical approach inherent in certain Marxisms, which assume an automatic connection, for instance, between working classes and socialist ideas, or ruling classes and ruling ideas. Hegemony, Hall insists, emerge through complex processes of articulation and interpellation: “Ideas only become effective if they do, in the end, connect with a particular constellation of social forces. In that sense, ideological struggle is part of the general social struggle for mastery and leadership – in short for hegemony. But ‘hegemony’ in Gramsci’s sense requires, not the simple escalation of a whole class to power, with its fully formed ‘philosophy’, but the process by which a historical bloc is constructed and the ascendancy of that bloc is secured. So the way we conceptualize the relationship between ‘ruling ideas’ and ‘ruling classes’ is best thought in terms of the processes of ‘hegemonic domination’. (43-4)

- He is fully appreciative of and utilizes effectively Gramsci’s notion of organic philosophy as the contradictory yet critically important way of thinking utilized by ‘ordinary’ people. This philosophy or common sense, he asserts, has within it elements of conservatism and of progress towards something new, and by implication must be engaged with from an approach of critical respect. “But what exactly is common sense? It is a form of ‘everyday thinking’ which offers us frameworks of meaning with which to make sense of the world. It is a form of popular, easily-available knowledge which contains no complicated ideas…It works intuitively, without forethought or reflection. It is pragmatic and empirical…” (Hall and O’Shea 2013:8) This approach, I suggest, is at the heart of Hall’s outlook, because it not only suggests his deep respect for ordinary people and their perspectives, but underwrites his open, non-hierarchical approach to politics.

- Closely wedded to this and elaborated in more detail in his iconic essay ‘What is this Black in Black Popular culture’ is a consistent anti-essentialist grain. The essay is itself a paean against the elevating of racial or cultural blackness as a bulwark against racism. Hall first argues that we need to deconstruct racism itself and appreciate that it is not static in order to also appreciate that anti-racist thinking cannot afford to become a victim of the same essentialist thinking that makes racism abhorrent: “The moment the signifier ‘black’ is torn from its historical, cultural and political embedding and lodged in a biologically constituted racial category, we valorize, by inversion, the very ground of the racism we are trying to deconstruct”. (Morley and Chen 1996: 472)

- Hall’s perspective is always elaborated through an approach that can be called ‘thinking through the conjuncture’. Again, he usefully adopts Gramsci’s notion of the social conjuncture as the array of articulated social forces, ideas and culturally tendencies in a given moment, as a particularly effective and robust lens with which to view and understand contemporary reality. It allowed him, captured most famously with Martin Jacques in his characterization of ‘New Times’ to appreciate the changing social relations in Britain in the Eighties and to theorize and predict the rise of Thatcherism and Neo-Liberalism: “If ‘post-Fordism’ exists then it is as much a description of cultural as of economic change. Indeed, that distinction is now quite useless. Culture has ceased (if ever it was-which I doubt) to be a decorative addendum to the ‘hard world’ of production and things, the icing on the cake of the material world. The word is now as ‘material’ as the world. Through design, technology and styling, ‘aesthetics’ has already penetrated the world of modern production. Through marketing, layout and style, the ‘image’ provides the mode of representation and fictional narrativization of the body on which so much of modern consumption depends. Modern culture is relentlessly material in its practices and modes of production. (233)

- I end with Hall’s far less referenced perspectives on international politics, which are critically important for our purposes. These were forged at the time of the crushing by the Soviet Army of the Hungarian Revolution (see Blackburn 2014: 77; Derbyshire, 2012) and the Khrushchev revelations concerning the brutal, authoritarian nature of Stalin’s rule. These I suggest, inoculated him against any romantic view of the Soviet Union as the fountainhead of ‘really existing socialism’ and any illusion that the USSR was the automatic bulwark of defense against imperialism for the newly independent countries. It also forced him, along with many of his generation who formed the British New Left, on to the back foot in order to rethink Marxism from the ground up, without a set of already successful prescriptions just waiting to be applied and with a willing and able physician standing ready in the wings.

We can best summarize the heart and essence of Hall’s work through the words of one of his critics. Despite his expressed reservations as to whether his academic preoccupations could ever be converted into a genuine praxis, Chris Rojek nonetheless generously proposes that “Hall’s politics favors widening access, exercising compassion, encouraging collaboration and achieving social inclusion”. (Rojek 2003: 193) Many of these features were either absent or incorporated into hierarchies of authority and exclusion in both the theoretical approaches and application of 1970s Caribbean Marxism-Leninism.

Caribbean Marxism-Leninism

To begin with Hall’s international perspectives first, it is fair to say that Caribbean Marxism-Leninism, if nothing else, held a remarkably un-historic view of the Soviet Union, leaping across time from the glory moments of the 1917 October Revolution, via the Red Army’s heroic defense and victories against Nazi Germany to the contemporary (1970s-80s) period. Elided entirely is mention of the brutality of collectivization, the Stalin show trials, Trotsky’s assassination or any reference to Khrushchev’s revelations about Stalin after his death. No mention, of course, is made of the Hungarian events or of the much more contemporary Czechoslovakian Spring and Soviet invasion of 1968. Two quotes from Trevor Munroe’s booklet Social Classes and National Liberation, derived from a series of ‘socialism lectures’ given to students in the early Seventies, suggests the tone and tenor of the times. In relation to the significance of the Soviet Union:

The Russian Revolution, therefore, did these three things: mash down the colonial system, mash down feudal exploitation and mash down capitalist exploitation in one-sixth of the world in October of 1917; and on those foundations began to build a new life, a new society in which no class lived on the backs of the labor of any other class…The great October Socialist Revolution broke forever and ever the monopoly of the capitalist class on power and when I say power, I mean every kind of power. (Munroe 1983: 29-30)

And on the relationship between ‘socialism’ (i.e. the Soviet Union and its allied countries) and the National Liberation Movement:

The very existence of socialism is the biggest help to the National Liberation Movement, even when the leaders of particular countries under imperialism completely reject and are totally against socialism, it is still the biggest help to the whole area of National Liberation…Therefore, we say that the alliance between socialism and National Liberation is a natural thing because socialism is the biggest force against imperialism and imperialism is the block to National Liberation. (33)

Looking back now on this simplistic, severely edited version of history to which many young, otherwise thoughtful students and young people in the Caribbean were so easily won, the search for the reasons as to why is not easily answered, but among them I suggest:

- The decisive defeat of the Left in Jamaica in the Fifties with the expulsion of the four leaders of that tendency (the Four H’s) from the PNP. This effectively silenced debates around Marxism and its role in national liberation for two decades (see Bertram 2016:231-240) and particularly at a moment in the fifties when Hall and many others were forging their radical perspective, but in the full glare of Hungary and of Khrushchev’s famous speech.

- The banning of Left-Wing literature in Jamaica in the Sixties, which made virtually all radical literature contraband, along with the emerging Black Power literature (and tragi-comically, Anna Sewell’s novel ‘Black Beauty’ among them!)

- The re-emergence of legal Marxist literature in the Seventies, following the election of Manley to power in 1972, but with titles and ideas drawn almost exclusively from the Soviet presses, Novosti and Progress. Thus, works by Brutents, Ulyanovsky and others on national liberation and the role of the Socialist countries, which were written precisely to eliminate swathes of contemporary history, were the only easily available literature and became the dominant sources of information for this eager and thirsty generation.

- The example of neighboring Cuba in which the Soviet Union had given generous support was interpreted as an exemplary instance of ‘proletarian internationalism’ and in which it was assumed that the Soviet Union would replicate this assistance in each and every instance in which there was a revolution against imperialism.

- The stance of Maoist China particularly in its attitude to liberation movements in this period is also relevant. As the potential alternative pole of “really existing socialism”, China might have provided an option for radically oriented youth to coalesce around. However, on almost all the touchstone questions, whether support for North Vietnam, choice of allies in the liberation movements against Portuguese colonialism, or solidarity with the Cuban Revolution, the Chinese supported positions and movements which seemed to place them on the wrong side of history. The default position was support for the Soviets, who were solidly behind Vietnam, the Cubans, the MPLA, FRELIMO, the PAIGC and others.

The overall effect of this was the emergence of an intellectual mindset which was less concerned with the fine-grained understanding of the local situation, the broad terrains of ideological struggle and how these interacted with the international, (indeed, a Hallian, conjunctural approach,) as it was convinced that the arrow of history had already been launched and was on its straight and accurate flight. From such a vantage point, events were already overdetermined by the revealing truths of Marxism-Leninism and the social and political leaps and advances of really existing socialism. All that was required was to make the local revolution, if a revolutionary situation emerged and join the stream of the victorious worldwide socialist and national liberation movements.

In contrast to Hall’s conception of organic philosophy and the need to respectfully engage in a conversation, with the inevitable elements of give and take, Caribbean Marxism-Leninism overtly adopted the notion that the majority of the working class was backward, both culturally and ideologically and thus needed to be taught and guided by the advanced elements. So, in the WPJ booklet The Working Class Party: Principles and Standards the conclusion is drawn that:

So the first thing we need to understand about the position of the working class in capitalist society and the effects of capitalism on the working class and on the working people is that the system itself makes the vast sections of the working class backward at the same time as it makes a small section advanced. (Munroe 1983: 15)

This led inevitably to the corollary that the party, the vanguard, had to be the instrument to bring consciousness to the majority of backward workers, best exemplified in Maurice Bishop’s oft-quoted 1982 “Line of March for the Party” speech to NJM cadres:

And the fifth point, the building of the Party, because again it is the Party that has to be at the head of the process, acting as representatives of the working people and in particular, the working class. That is the only way it can be because the working class does not have the ideological development or experience to build socialism on its own. The Party has to be there to ensure that the necessary steps and measures are taken. And it is our primary responsibility to prepare and train the working class for what their historic mission will be later on down the road. That is why the Party has to be built and built rapidly, through the bringing in the first sons and daughters of the working class. (Seabury and McDougall 1984: 73)

Reading this speech again after many years, its deeply patronizing essence is even more evident. Indeed, Bishop’s invocation here goes beyond the typical vanguardist argument, in the suggestion that the party in this instance is not just the vehicle of the advanced workers, but a substitute for them, until such time as they can be brought into the organization and educated up to the required advanced standing. If there is any central feature then of Caribbean Marxism-Leninism that might be teased out for closer scrutiny, it is this hierarchical structuring of levels of consciousness with its implications of the necessity for tutelage and guidance, not only from the advanced workers – the more ‘Leninist’ formulation – but in the absence altogether of ‘advanced workers’ from the party, that is the undisguised tutelage of the intellectual stratum. Surely, this leads as night follows day, to the Grenada crisis of 1983. The Party derogated the right to modify its leadership structure at will, including the effective demoting of the leader and Prime Minister to joint leader, without any reference to the population and to what it might think. This led to a series of events which have been adequately discussed elsewhere and need not be repeated, marching in lockstep fashion, to Bishop’s death, the US-led invasion and the end of radical Caribbean politics for a generation.

What If?

As this short essay began, somewhere during the Nineteen Sixties, Stuart Hall took a decision to lay his bed permanently in the United Kingdom, where he helped to build the formidable discipline of cultural studies at Birmingham, thereby influencing a generation of scholars in the UK and contributing immeasurably to critical global political and cultural discourse in Britain, Europe, the USA and beyond. The enigmatic question of course, which can never be answered, is what would have been the outcome had he brought his formidable intellect and his remarkably fluid and democratic theoretical approaches to bear on his own Jamaica of the 1960s, the very country in which a popular upheaval with region-wide consequences was ignited in 1968. What would the radical movement of the Seventies have looked like with a Stuart Hall contending with some of the more dogmatic, hierarchical and wooden perspectives that came to dominate in the radical Jamaican space? Perhaps it might have made little difference, (as indeed was the case with CLR James and his supporters across the Anglophone Caribbean) as the international environment may well have weighed decisively in favor of the rise of pro-Soviet, Marxist-Leninist tendencies that did, in fact briefly gain momentum and enjoyed their moment in the sun. But perhaps with his prestige and fluency and his possessing the undoubted, if ironic cachet of being a Rhodes Scholar, Stuart Hall, returning from the United Kingdom, might have been taken seriously and might have influenced the emergence of a more flexible, open, radical and popular movement in Jamaica. What would this have meant for the course of events in that country and more so, for the entire Caribbean, including, most of all Grenada, where the Gairy regime had created a political opening and the groundwork had already been laid for more insurrectionary forms? History evidently didn’t follow this course, but it is worthwhile to muse about the far-reaching consequences if it had.

Brian Meeks is professor and chair of Africana Studies at Brown University. He has published many books and edited collections on Caribbean Revolutions, Caribbean thought and questions of hegemony and power in contemporary Caribbean politics. He taught at the University of the West Indies, Mona campus for many years.

References

Austin, David. 2010. “Vanguards and Masses: Global lessons from the Grenadian Revolution.” In Learning from the Ground Up: Global Perspectives on Social Movements and Knowledge Production edited by Aziz Choudry and Dip Kapoor, 173-189. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Austin, David. 2013. Fear of a Black Nation: Race, Sex and Security in Sixties Montreal. Toronto: Between the Lines.

Bertram, Arnold. 2016. N.W. Manley and the Making of Modern Jamaica. Kingston. Arawak Publications.

Bishop, Maurice. 1984. “Line of March for the Party.” In The Grenada Papers, edited by Paul Seabury and Walter A. McDougall, 59-88. San Francisco: Institute for Contemporary Studies.

Blackburn, Robin. 2014. “Stuart Hall: 1932-2014.” New Left Review 86, March-April 75-93.

Bogues, Anthony. 2015. “Stuart Hall and the World We Live In.” Social and Economic Studies 64:2, 177-193.

Chen, Kuan-Hsing. 1996. “The Formation of a Diasporic Intellectual: An Interview with Stuart Hall.” Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, edited by David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen, 501-2. London and New York: Routledge.

Clarke, Robert. 2014. “Statement on Grenada by Robert “Bobby” Clarke October 14, 2009.” Cited in Brian Meeks Critical Interventions in Caribbean Politics and Theory, 113. Jackson. University Press of Mississippi.

Derbyshire, Jonathan. 2012. “Stuart Hall: We Need to Talk About Englishness.” New Statesman August 23 www.newstatesman.com

Girvan, Norman. 2010. “New World and its Critics.” In The Thought of New World: The Quest for Decolonisation, edited by Brian Meeks and Norman Girvan. Ian Randle Publishers: Kingston and Miami.

Hall, Stuart and Allan O’Shea. 2013. “Common Sense Neoliberalism.” Soundings, 55, Winter. 8-24.

Hall, Stuart. 1988. “The Toad in the Garden: Thatcherism among the Theorists”. In Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture edited by Carey Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, 35-73. Urbana and Chicago: The University of Illinois Press.

Hall, Stuart. 1996. “The Meaning of New Times.” In Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues. Morley and Chen eds. 225-237.

Hall, Stuart. 1996. “The Problem of Ideology: Marxism without Guarantees.” In Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, edited by David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen, 25-46. London and New York: Routledge.

Hall, Stuart. 1996. “What is this Black in Black Popular Culture?” In Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues. Morley and Chen eds. 465-475.

Lewis, Gordon K. 1987. Grenada: The Jewel Despoiled. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

MacCabe, Colin. 2008. “An Interview with Stuart Hall: December 2007.” Critical Quarterly 50 nos. 1-2.

Marable, Manning. 1987. African and Caribbean Politics: from Kwame Nkrumah to Maurice Bishop. London: Verso.

Mars, Perry. 1998. Ideology and Change: The Transformation of the Caribbean Left. Kingston: The University of the West Indies Press.

Meeks, Brian ed. 2007. Culture, Politics, Race and Diaspora: The Thought of Stuart Hall. Kingston: Ian Randle Publishers and London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Meeks, Brian. 1993. Caribbean Revolutions and Revolutionary Theory: An Assessment of Cuba, Nicaragua and Grenada. London and Basingstoke: Macmillan Caribbean.

Meeks, Brian. 1996. Radical Caribbean: from Black Power to Abu Bakr. Kingston: The University of the West Indies Press.

Mills, Charles. 2007. “Stuart Hall’s Changing Representation of “Race.” In Culture, Politics, Race and Diaspora: The Thought of Stuart Hall, edited by Brian Meeks, 120-148, Kingston: Ian Randle publishers.

Munroe, Trevor. 1983. Social Classes and National Liberation in Jamaica. Kingston: Workers Party of Jamaica.

Puri, Shalini. 2014. The Grenadian Revolution in the Caribbean Present: Operation Urgent Memory. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Quinn, Kate ed. 2014. Black Power in the Caribbean. Gainesville Fl. The University Press of Florida.

Rojek, Chris. 2003. Stuart Hall. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Ryan, Selwyn and Taimoon Stewart eds. 1995. The Black Power Revolution 1970: A Retrospective. Trinidad: ISER.

Scott, David. 2014. Omens of Adversity: Tragedy, Time, Memory, Justice. Durham: Duke University Press.

Notes

[1] James’s notions of a non-vanguardist, spontaneous movement of the people had some initial influence particularly through the Antiguan, Grenadian and Trinidadian movements, but as I have argued elsewhere, James had no developed strategy for insurrection, beyond the advocacy of popular spontaneous uprising. When an insurrectionary situation arose, as in Grenada between 1974 and 1979, the NJM therefore turned to the old playbook of the underground vanguard, which turned out to be an effective tool for overthrowing the Gairy regime, but not for popular rule in the aftermath. The other factor was the clearly compelling international situation, in which, in the seventies Cuba, based on booming sugar prices seemed to be thriving, the Vietnamese had liberated their country and the liberation movements had achieved independence through guerrilla warfare in Angola, Guinea Bissau and Mozambique. All were led by Marxist-Leninist parties, raising significantly the cachet of this trend. See Meeks 1996: 72 ;1993: 178 and Austin 2010: 173-189)

[2] I want to nuance Perry Mars’s argument in which he suggests that the weaknesses that led to the demise of the Caribbean Left lay more in questions of leadership, than ideology. There is much truth and indeed, I am invested in the argument that it was the leadership and its failures which contributed immeasurably to the crisis in Grenada with its debilitating impact on the Left in general. However, the role of ideology has been underplayed, or presented as a stock word or phrase, such as ‘Leninism’ or sometimes even ‘Pol Potism’ which unfortunately is a lazy alternative to more careful analysis. Ideology in the end informed the leadership and shaped the framework and boundaries of their decision-making. It thus needs far more careful scrutiny in the new round of scholarship that will eventually appear on this period. (Mars 1998: 162)

[3] Both Chris Rojek and Charles Mills can be considered as among Hall’s more respectful critics, acknowledging what they consider his important theoretical advances yet remaining weary as to whether, in the case of Rojek, his emphases on difference and anti-essentialism have not undercut the ability of his project to have an impact on real political life. Rojek asks, “Can difference be the basis for effective political agency?” (Rojek 2003:187) Charles Mills’ misgivings include the suggestion that Hall’s fabled eclecticism, in seeking, for instance, to utilize both Gramscian notions of hegemony with its implications of a dominant class/bloc and Foucauldian notions of dispersed power, may in the end be incompatible. He pleads “How could it be possible to test and verify or falsify a theoretical mélange with so many conflicting components?” (Meeks 2007: 141) the detailed exploration of these genuine questions certainly remains legitimate, but go somewhat beyond the purposes of this short engagement.

Leave a Reply