Ilan Stavans, I Love My Selfie (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017)

Ilan Stavans, I Love My Selfie (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017)

reviewed by Nicole Erin Morse

This essay has been peer-reviewed by the boundary 2 editorial collective.

The figure of Narcissus haunts both popular and academic discussions of selfies. Usually, his absorption with his own image is taken to stand in for the experience of creating selfies, while his death beside his reflection is read as a warning about the perceived negative consequences of this image-making practice. Framed in this way, selfies are described merely as a symptom of a narcissistic era and as the cause of further cultural narcissism. And while narcissism may indeed be a central feature of selfie practices, accounts of selfies that focus on their narcissism tend to be so disturbed by the cultural practice that they neglect any consideration of the formal and aesthetic properties of specific images. Furthermore, the myth of Narcissus is not so simple, and in linking selfies to the Narcissus myth, the other principle character is always excised from the telling: Echo. Yet in Book III of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Echo’s role is significant, and although her character is often read primarily as a parable of the conflict between sound and image, the figure of Echo also has critical implications for our understanding of selfies. Echo, the nymph who cannot speak for herself, falls in love with a man who cannot recognize himself, their twin inadequacies fueling her passion for him at the same time that they ensure that reciprocal love between the two is impossible. Ultimately, Echo is the witness to Narcissus’ passion for his reflection and her voice transforms the glade in which Narcissus discovers his own image into a space that responds to and repeats his dying words to himself. Echo’s voice turns Narcissus’s endless invocations of his love and desire for his mirror image into something that has an element of reciprocation: a call and response. Within discussions of selfies, the figure of Echo should remind us that selfies are addressed to others, with the role of reception challenging any account of digital self-representation that presents it only as a closed or solipsistic loop—a relationship between self and reflection that involves no others.

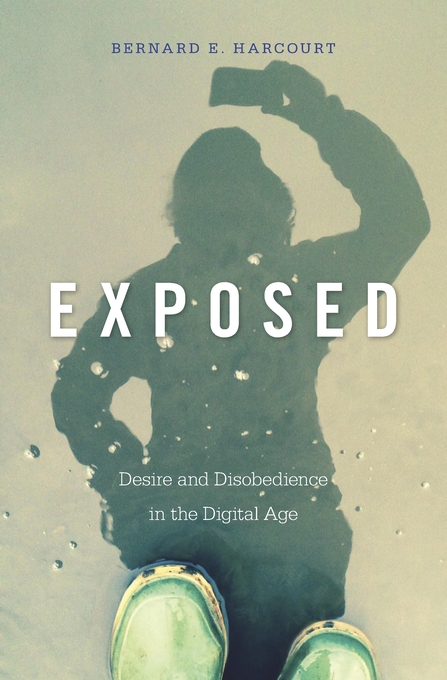

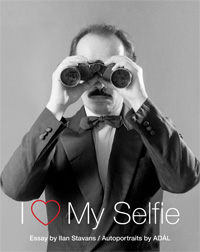

Commentary on selfies is divided between two general trends, one that condemns selfies for their narcissism and one that attempts to redeem selfies from the charge of narcissism by arguing that selfies invite or produce interpersonal relationships (Goldberg 2017, 1), but in both cases, the actual formal specificity of individual images is elided. Curiously uniting these two trends, critic Ilan Stavans’ and artist Adál Maldonado’s I Love My Selfie (2017) reads selfies through Narcissus and condemns their narcissism without ever mentioning the role of Echo. Indeed, Maldonado, otherwise known as ADÁL, describes his participation in the project thus: “I wanted to create an exhibition in which I compare the self-portrait as an artistic expression versus the selfie as a narcissistic expression” (ARC Magazine 2014). Yet as a collaborative volume, created by an artist and by a critic who deeply admires that artist, the book’s very structure stresses relationality. As Stavans narrativizes his encounter with ADÁL, his enthusiasm for ADÁL’s work and his admiration for the artist shape the entire text, as he strives to turn ADÁL’s stylized, black-and-white self-portraits from the 1980s and 1990s into a commentary on contemporary selfies. Both Stavans and Adal have produced immense bodies of work independently of their collaboration, and it is not my intention here to contextualize this particular project within their larger oeuvres. Instead, I contend that, although I Love My Selfie points the way toward many of the most compelling questions about selfies, nonetheless, Stavans’ and ADÁL’s collaboration does not answer these questions. Instead, it offers, by way of illustration, a demonstration of some of the issues that currently hinder selfie scholarship more broadly. Ultimately, although it is titled I Love My Selfie, this book is far less concerned with selfies than it is interested in self-portraits. And as the volume details the relationship between the artist and the critic, both selfies and self-portraits serve as a vehicle through which Stavans meditates on the nature of the self. In so doing, I Love My Selfie demonstrates how difficult it is for critics to talk about selfies without turning immediately to other representational practices and to seemingly more important topics—in other words, it seems to be extremely difficult to take selfies seriously on their own terms as aesthetic, political, and theoretical texts.

Repeatedly, when new media have emerged, there is a tendency to argue for their value by analogizing them to more established art practices. For selfies, this tendency is often encapsulated in the seemingly ever-present urge to compare them to the work of photographer Cindy Sherman—always to the detriment of selfies—so that even when Sherman herself began taking selfies and sharing them on Instagram, The New York Times asserted that this only revealed “the gap between Ms. Sherman’s vital, unsettling practice of sideways self-portraiture and the narcissistic practice of selfie snapping” (Farago 2017). In I Love My Selfie, this pattern surfaces within Stavans’ persistent privileging of ADÁL’s self-portraits over more vernacular selfie practices. It also emerges in their joint assessment of ADÁL’s black-and-white style as a kind of “Nazi Tropic Noir” (118), which Stavans then attempts to further legitimize by describing how it invokes the work of Leni Riefenstahl, “the German director of films like Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will), whose critique of fascism was done from inside the Third Reich” (118-119). This sentence alone should give us pause. The fact that Stavans so easily accepts Riefenstahl’s post facto justification of her work as a critique—rather than an embodiment—of fascist aesthetics is troubling in its eschewal of established critical consensus. Even so, what is especially striking about this in context is the extent to which Stavans goes in his persistent attempts to validate ADÁL’s self-portraiture by aligning it with fine art practices and against vernacular snapshot photography.

Despite the surprise of its politics, this is an unsurprising move by Stavans. As artists have begun exploring selfies as a realm for art practice, a variety of efforts have been made to delineate what distinguishes artistic uses of selfies from vernacular selfies. For example, the #artselfie project seeks to position selfies in relation to art by curating selfies taken in proximity to classical art works (#artselfie 2014; Droitcour 2012), while a recent exhibition of selfies in London was organized around the principle that artistic intention differentiates vernacular selfies from selfies that are worthy of being considered art (Jones 2013). Tulsa Kinney describes her first encounter with Zackary Drucker’s and Rhys Ernst’s Relationship thus: “At first glance, thumbing through, they look like a lot of selfies—if they weren’t photographs.” Distinguishing between selfies and “photographs,” Kinney asserts that she subsequently realized that “These were far from selfies. These are of the fine craft of art photography with an edge, with hints of Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, and maybe a little Cindy Sherman” (2014). Courting controversy at the boundary between vernacular selfies and art works, artist Richard Prince transformed appropriated selfies from Instagram into works that sold for up to six figures by blowing up the original photos and adding emoji captions (Parkinson 2015). Finally, artists like Audrey Wollen and Melanie Bonajo undo the very logic of selfies, exploring negative affect through self-portraits and what Bonajo calls “anti-selfies,” or images that reject those qualities of selfies strongly associated with their vernacular use, such as their polished self-presentation and positivity (Barron 2014; Capricious 2014). Amid such boundary negotiations, what disappears in commentary on selfies, including Stavans and ADÁL’s work, is the question of what individual selfies—whether artistic or vernacular—actually do.

Instead, the heart of this book is Stavans’ recognition of a kindred spirit in ADÁL, his admiration for the artist, and, finally, Stavans’ own narration of his personal experience. Given this, a more appropriate title for the book might be “I ♥ ADÁL,” or even ADÁL’s original, antagonistic title for his photography series: “Go F_ck Your Selfie.” Here, selfies and self-representational art are not a sustained object of art historical inquiry but instead the catalyst for the narrative of a relationship between artist and critic. As a result, personal narrative or loosely-structured memoir is the form of self-representation that permeates a volume that actually features few selfies. After encountering ADÁL’s self-portraits, Stavans is inspired to reach out to him, and eventually makes contact. As Stavans tells it, in approximately 2013, ADÁL asked if Stavans “would be interested in exploring together the nature—make that the ‘condition’—of the selfie as a newly arrived art form”; Stavans adds, “the sheer question sent my mind into a roller-coaster ride” (38). Stavans describes the questions that he and ADÁL wanted to answer through their collaboration, but he seems to be unaware that these questions had already been asked and answered (largely by cisgender women and transgender artists) in exhibitions and collections that emerged well-before this volume went to press. Critically, these interventions speak more to the formal and aesthetic possibilities of selfies than to their availability for representational politics. For example, the question of whether selfies should be exhibited at MoMA was certainly at issue in 2014 when Relationship, a photographic series that opens with several selfies, was included in the Whitney Biennial (Drucker and Ernst 2016). Additionally, as Stavans and ADÁL were beginning their collaboration, the question of whether “anti-selfies” exist was being actively explored by feminist artists (Barron 2014; Capricious 2014). However, inspired by ADÁL’s questions, Stavans travels to visit the artist, proposing that they should “take out-of-focus selfies” together (38), building on ADÁL’s long history of taking self-portraits with soft focus.

Because Stavans understands selfies through self-portraiture, there is a constant tension between the move to historicize selfies as an evolution of self-portraiture and the unrealized attempt to distinguish selfies from self-portraiture. As a result, it is difficult to determine whether Stavans’ conclusions about self-representational art—developed through reflections on painted self-portraits and ADÁL’s photography—even apply to selfies. Though Stavans indicates that there are a variety of distinctions between selfies and self-portraiture (114, 120), it seems that, for Stavans, the primary differences are related to technology, with selfies characterized by the fact that they are taken with consumer-grade digital electronics and recognizable because of the typical compositions that follow from this fact. In this vein, ADÁL asserts, “for a photograph to be a selfie, it needs to be taken with a cell phone or on a laptop. The entire aesthetic is that of a photographic image created digitally, by the cyberculture with cybertools, with the cybernet in mind” (119). Even though ADÁL allows that some selfies could be taken with a laptop, which introduces a degree of compositional flexibility, Stavans suggests that selfies are identifiable as such because of the typical composition that results from holding a front-facing smartphone camera at arm’s length (32), stating that the problem with selfie-sticks is that they make “selfies look unselfie-like” (38). Although these distinctions between selfies and self-portraits are not as clearly developed as they could be, one thing seems certain: based on these categorical definitions, almost none of ADÁL’s photographs in this volume, around which Stavans’ discussion of selfies develops, are actually selfies.

Indeed, there are few selfies in the volume at all—six or seven out of the seventy-four total images—and as a result most of the specific analysis of individual images concerns self-portraits. Furthermore, because Stavans and ADÁL assert that there are rigid distinctions between selfies and self-portraits, it is unclear to what extent Stavans’ meditations on the self and on self-representation even apply to selfies; in any case, these musings do not appear to arise from the selfies reproduced in the volume. Chapter Six is primarily concerned with self-portraiture, and in it Stavans uses self-portraiture as a springboard for pondering narcissism, gesturing obliquely to selfies when he writes, “we aren’t more narcissistic than our predecessors; we simply have more tools to parade that narcissism. They might not be better, but they surely are more efficient” (99). Caught between a technological determinism in which photography thoroughly changes the nature of art (103) and a confident claim that the only difference between a Rembrandt self-portrait and a selfie is that “the tools are different” (102), Stavans attempts to historicize selfies through self-portraiture. Yet the history of self-representation that Stavans offers is not only inconsistent but unpredictable. On the one hand, he emphasizes the technological shift that distinguishes selfies from painting and photography (103). On the other, he elides this distinction when detailing the history of ADÁL’s work; in discussing ADÁL’s “series on the selfie,” Stavans writes, “Adál started it while living in San Juan in 1987 and continued it in New York, where he returned in 1988” (118). The problem here is that, as Stavans notes, the “invention” of the word “selfie” is generally dated to 2002 (4), and in any case the consumer-grade digital technologies that ADÁL and Stavans regard as essential to selfie production were certainly not widely available in 1987; moreover, ADÁL’s series, reproduced in this volume, was initiated in the 1980s through analog photography (118). Unable to resolve the contradiction between a technologically deterministic position and an account of selfies that locates their “selfieness” elsewhere, Stavans’ attempt to offer a genealogy of selfies remains inconclusive.

Despite the limitations of his argument, Stavans’ key intuition that selfies might be understood in dialogue with self-portraiture is significant, as putting pressure on the definitions of selfies and self-portraiture—whether in the present moment or across the history of photography—can yield rich insights. For example, in her analysis of the early-twentieth century photographs usually attributed to Claude Cahun, Tirza True Latimer argues that these photographs of Cahun—almost all of which have been posthumously titled “Self-Portrait”—should not be understood as self-portraits so much as collaborative performances, given that they were created with Cahun’s partner and lover, Marcel Moore. According to Latimer, the discourse of self-portraiture that has followed Cahun elides the collaborative, queer relationship that was inextricable from her—actually their—work. Through close analysis of these photographs, Latimer identifies what she describes as “statements of or about Moore’s participation in the creative process within the work itself” (2006, 56), statements that emerge through formal techniques including reversals, doubling, and in particular the intrusion of the photographer’s shadow into the frame of the photograph. Beyond Latimer, other scholars also argue for a reconsideration of the status of Cahun’s “self-portraits,” with Abigail Solomon-Godeau emphasizing the relationality of the body of work. She argues that, since Moore was not only the photographer but also the audience to whom the photographic poses are addressed, the photographs should not be understood as female representation, which places undue stress on the individual subject of the photograph, but rather as lesbian representation, to capture the relationship between the subject and the photographer (1999, 117). In one example of the complex relationality captured in these photographs, an image from 1927 shows Cahun, in vampire-style makeup, gazing into the camera while holding a reflecting ball. In the depths of the reflective orb, shadows suggest the presence of a photographer, and yet the obscurity of the image doesn’t offer the viewer a clear understanding of the photograph’s production situation. Instead, we are drawn into the image’s depths, seeking out a glimpse of the person to whom Cahun’s direct look is addressed. Although such efforts to reassert Moore’s role in Cahun’s “self-portraits” are compelling and necessary, at the same time, the fact that these collaborative queer images are described as “self-portraits” opens up the possibility of asking to what extent the self is always collaborative and relational.

While Cahun and Moore’s Surrealist collaborations from the 1920s and 1930s might seem quite distanced from contemporary selfie practices, artistic practices like their “self-portraits” can illuminate how contemporary selfie practices offer an exploration of “the self” that is always-already relational, formed through multiplicity, reflection, and doubling. Such possibilities appear in Drucker’s and Ernst’s Relationship series, which begins with several selfies shot with an inexpensive digital point-and-shoot camera, and employs the visual rhetoric of doubling to capture fleeting moments from the artists’ six-year relationship. Although Relationship also contributes to trans visibility, demonstrating selfies’ role in representational politics, it is the formal particularities of Relationship’s images that make the series such a rich exploration of the possibilities of selfies. Across the series, Drucker and Ernst double each other through pose, gesture, and other formal strategies, ultimately challenging the idealism of the singular, unified self (in part by explicitly complicating the use of the Lacanian mirror stage to understand self-representational art). Rather than valorize the discrete, bounded, and separate individuated self, Drucker and Ernst employ shadows and silhouettes to repeatedly represent themselves as a unified, doubled body, in images that evoke Aristophanes’ account of love from Plato’s Symposium. In one such image, titled “Flawless Through the Mirror,” the two figures stand near each other, not quite touching, the distance between them emphasized by the wide-angle lens while shadows create a distinction between Drucker’s arm and Ernst’s body. [FIG 1] However, thrown—or projected—onto Ernst’s body, Drucker is doubled in two shadows that overlap and intertwine, producing a single compound figure with four arms, and the hint of two faces, with this vision of the double-bodied being appearing within the larger photograph. As an image-within-the-image, this silhouette’s flatness contrasts with their material bodies, and its dissolution of boundaries highlights, by contrast, the very real distance between them. Staging the desire for this idealized union, along with its real impossibility, the melancholy, blue-tinged photograph shows Drucker’s and Ernst’s bodies serving as the literal support for an image of love and wholeness that—the photograph tells us—can only be produced through representational trickery.

Although admittedly, many selfies might offer more limited opportunities for artistic expression and critical analysis, the possibilities of selfies are indicated by such intricate accounts of the self in relation. Moreover, the way in which work like Drucker’s and Ernst’s evokes the messiness of self-constitution reveals the inadequacies in Stavans’ emphasis on the way that ADÁL’s work represents an autonomous, agential, and singular self. This model of the self is expressed through the gendered language Stavans uses to discuss selfies, as well as through the duo’s disavowal of and disdain for most vernacular selfie practices, practices which are associated with young women. Thus, a description of “an adolescent photographing herself half-naked in a compromising position” (37-38)—an off-handed, dismissive, yet highly gendered description of selfie practices—immediately follows Stavans’ praise of a self-portrait by ADÁL that also includes “a woman, her curves emphasized”—emphasized, obviously, by the artist, rather than by the woman’s own agency. Furthermore, right after Stavans’ description of the half-naked teenage girl “in a compromising position” Stavans returns to his valorization of ADÁL’s masculinity, writing that in his self-portraits, ADÁL’s “pose is invariably stolid. He looks stern, even defying” (38). Here, Stavans emphasizes the stern, dominant masculinity of ADÁL’s pose, implicitly claiming that, even though ADÁL is engaged with his own image, it is as art rather than narcissism. And since narcissism as pathology has long been linked to both femininity and homosexuality (Goldberg 5-7), Stavans’ attempts to deny ADÁL’s narcissism while stigmatizing vernacular selfies for their narcissism are in the service of asserting that ADÁL’s work is straight rather than queer. It seems that the kind of self-representation in which Stavans is interested is emphatically not that of the adolescent exploring her sexuality—nor is it what Stavans describes as Kim Kardashian’s “anodyne, sexually explicit selfies” (16) nor even Frida Kahlo’s “exhibitionistic” self-portraits (106)—but instead, self-representation in which female sexuality functions as a prop to be utilized by a “stolid, stern,” and hence firmly masculine, male artist.

Here, Stavans is aligned with much of the discourse about selfies, for agentive female self-representation is often heavily critiqued in discussions of selfies, particularly when that self-representation includes overt sexuality (Burns 1723), and when criticisms of sexualized selfies deride such images as “attention-seeking” they discipline women’s independent sexual expression (1724). Of course, the fact that selfies might facilitate female self-representation is not enough to justify critical analysis that attends to their formal properties; rather, the fact that selfies are so routinely dismissed because of their overdetermination as feminine should give us pause. Across Stavans’ essay, anxieties about women engaging in independent self-representation are expressed through gendered and sexualized language that suggest an attempt to discipline unregulated female agency through continuously putting women in relation to men. For example, in reflecting on Frida Kahlo’s work, Stavans asserts that “she usurps the spotlight reserved to her husband Diego Rivera, always perceived as the better artist” (28)—a concern about a woman usurping a man’s rightful place that uggests more about Stavans than it illuminates about the reception history of Kahlo’s and Rivera’s work. After dismissing Kahlo, Stavans turns to a two-page-long history of the photograph of Sharbat Gula—a young, female Afghan refugee famously featured on National Geographic Magazine’s June 1985 cover. As he speculates about how the image would have been different if it had been a selfie, asking whether self-representational photography by a woman might be “less assured, more confusing” than a portrait by a male photographer, Stavans also notes that the thirty-five-year-old National Geographic photographer could have been the twelve-year-old Gula’s “father,” adding nonchalantly, “he could also have been her lover” (32). Stavans’ meditation on the famous photograph of the “Third World Mona Lisa” (29) concludes with a brief reflection on the original Mona Lisa (1503). Here, Stavans notes that a subsequent photograph of Gula in middle age “makes us feel grateful to Leonardo da Vinci for not having returned to La Giaconda…years after he made her portrait” (32).

Through their discussion of the place of women in images of self-representation, these pages illustrate that the central organizing principle of the book is not selfies themselves but rather Stavans’ own subjective encounter with them. And of course, Stavans is hardly the first critic to seek out the ontology of the image through offering deeply personal responses to particular images. Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida reflects on the nature of photography through intimate descriptions of Barthes’ experiences of select photographs, including a childhood photograph of his mother (1984). But in Stavans’ essay, photography has a different function from that which it serves in Barthes’ text, and rather than moving from diverse individual photographs toward wider claims about the medium, Stavans moves to a variety of other, loosely connected ruminations. As a result, the most incisive commentary in the section about Kahlo emerges only in Stavans’ description of the way Kahlo has been turned into a pop icon and a symbol of Mexican femininity. “Kahlo is no longer Mexican,” Stavans writes, “she is what the gringos have turned Mexico into.” What emerges in such passages is a literary self-portrait of a middle-aged Mexican man, one who can critique the global north’s subjugation of the global south, but one who seems to be far less aware of what his attitude toward images of women says about his ability to understand subjugation intersectionally.

This subjective lens also lands Stavans in other interpretive difficulties. Since he believes that selfies “promise smiles, happiness, and engagement” (4), he asserts that “certain topics become taboo,” noting immediately, as an illustration of this claim, “I have seen a selfie taken next to a corpse and found it nauseating” (5). It is likely that many people have similar experiences of selfies, and would respond similarly to selfies taken beside dead bodies. However, Stavans’ anecdote does not actually prove such an image is excluded from the category of selfies through a taboo—instead, what it shows is that such images do indeed exist, making selfies as a category more capacious than Stavans imagines. Instead of opposing the “smiles, happiness, and engagement” of selfies with the taboo of morbidity, a different approach might ask what happens when selfies unite the performance of happiness with the morbid or disturbing, such as in the Holocaust memorial selfies that Shahak Shapira criticizes on his website Yolocaust.de (Gunter 2017). Yet this is not a question that Stavans essay raises, as he notes instead that when he was in a Havana cemetery, “it never crossed my mind…to take a selfie” (5).

But what might a richer account of selfies offer us? Selfie scholarship itself frequently relies on the definition offered by Theresa M. Senft and Nancy K. Baym, who describe selfies as both objects and practices, writing:

A selfie is a photographic object that initiates the transmission of human feeling in the form of a relationship (between photographer and photographed, between image and filtering software, between viewer and viewed, between individuals circulating images, between users and social software architectures, etc.). A selfie is also a practice—a gesture that can send (and is often intended to send) different messages to different individuals, communities, and audiences. (2015, 1589, emphasis in original)

This nuanced definition of selfies as gestural as well as imagistic is echoed in other scholarship, with Matthew Bellinger and Paul Frosh asserting that selfies can be identified through pose and gesture rather than through the technical details of their production and circulation (Bellinger 2015; Frosh 2015).

Stavans can be positioned within this debate, although ultimately his work requires an attention to the restrictions within these seemingly expansive definitions of selfies. On the one hand, he is aligned with this trend in selfie scholarship, for at times his definition of selfies is exceedingly broad, extending far beyond the limited definition that selfies are “self-generated digital photographic portraiture, spread primarily via social media” (Senft and Baym 2015, 1588). On the other, because Stavans’ thought experiments about the boundaries of the category of “the selfie” put pressure on the flexible, reception-oriented descriptions of selfies offered by Bellinger and Frosh, they ultimately reveal the value in the kind of precision offered by Senft’s and Baym’s attention to the kinds of relationships selfies produce. For example, when Stavans uses the phrase “selfie taker” to describe the videographer behind the “amateur (i.e., domestic) video taken of the Rodney King beating in 1991” (112), his decision to engage with that video (as well as with other instances of video of police brutality) as a form of self-representation cannot be understood as simply one available spectatorial position among many others. Stavans’ interest in the “selfie taker [who] will step out of the frame” in order to capture a “selfie as incriminating evidence” (112) emphasizes the gesture that produces these videos rather than the violent acts captured therein. As a result, the relationships that selfies produce—in the spectatorial situation Stavans proposes—become relationships that turn on imagining the action of a witness to police violence (“stepping out of the frame”), rather than responding in outrage, disgust, or distress to this violence. As Stavans describes it, “the selfie as incriminating evidence” offers a way to escape from our interpolation into the position of witness to state-sponsored racist violence. Deliberately choosing to read such images as “selfies” functions as a distancing technique in which the murders of Amadou Diallo and Michael Brown become mere material for detached reflection on the nature of “the self.” Yet if these videos reveal anything about our selves, they reveal how identity is marked and far from universal, and hence hardly adequately captured by a singular noun.

Throughout scholarship on selfies, the relationship between selfies and the self is a persistent question. It seems natural to think that the encounter with the face of the other might prompt reflection upon the “self” thus encountered. However, in our contemporary moment, selfies are in fact an incredibly impoverished way to access information about the self—either our own selves or the selves of others. After all, as we navigate our networked world we produce “data doubles” that preserve traces of all of our online and much of our offline activity (Haggerty and Ericson 2000, 614), with these records of our purchases, searches, and movements arguably containing far more information about “the self” than a static image could convey. In fact, what we encounter in selfies is not a window into “the self” but the radical alterity of the face of an other. It in this context that Stavans’s fixation on using selfies to interrogate the nature of the self, and specifically, to propose that the self is a performance, falls short. Repeatedly, Stavans speculates about whether this means that the self is, therefore, inauthentic, highlighting this question immediately through the epigraph, a line from Polonius’s speech to Laertes in Hamlet in which the father tells his son: “This above all: to thine own self be true, and it must follow, as the night the day, thou canst not then be false to any man.” Paired with a comical self-portrait in which ADÁL poses with a banana superimposed over his face, the fruit standing in for a smile on the lips that it conceals, this epigraph leads Stavans to propose that the self is a performance that combines truth and falsehood. Noting that Polonius is hardly a model of transparency and truth, Stavans writes that the lines from Polonius’s speech express a paradox: “being true to one’s self means being fundamentally adaptable, contingent, provisional, all of which are attributes of falseness” (7).

For Stavans, this play between the true self and the false performance is at the heart of self-representation. Unlike the extensive scholarship that follows Erving Goffman’s and Judith Butler’s work on performance and performatives, however, Stavans appears to remain invested in the idea that a true self does in fact exist, and that it can even be identified and recognized. For example, in a statement that is as much a platitude as anything Polonius tells Laertes, Stavans writes of self-portraits: “the face is the portal through which the self finds expression” (106). The claim here is that the self can be recognized as authentic precisely when it is not a self-conscious performance, and Stavans contrasts Frida Kahlo’s paintings, which he dismisses as “exhibitionistic,” with more “authentic” images of female suffering by artist Ana Mendieta (106). For Stavans, Mendieta’s work is comparatively unique, as he presents self-representation, especially through selfies, as tarred by inauthenticity. This categorial distinction runs throughout. Writing about “felfies,” a hashtag that on Instagram that includes everything from “feline selfies” to “food selfies” to “filtered selfies” to “farmer selfies,” Stavans more narrowly defines them as false selfies that “look real” (122). He asserts that “felfies…misrepresent the past in a way that is egregious, not because they play on impossibilities but because the gesture depicted in them isn’t authentic to selfies, which in themselves are inauthentic items” (123). Although he does not elaborate on what gesture might be authentic to selfies, the inauthenticity of selfies seems to lie not only in their performative nature, but also in what Stavans sees as their inability to be self-aware and self-critical. While he embraces the Polonius speech for its irony (3), and celebrates Montaigne’s account of the self because of the ironic tone of “Of Cannibals” (23), Stavans seems unable to see selfies as capable of similarly ironic expression. Instead, Stavans can only locate such self-aware commentary on the relationship between self-representation and the self in ADÁL’s self-consciously artistic self-portraits. For Stavans, these portraits capture the paradoxical play of truth and falsehood that he identifies as the essential nature of the self. The collection of ADÁL self-portraits, he writes, “feels to me absolutely true, even authentic, yet it argues that the self is a mask, that our identity is in a constant state of flux” (38). From this position, selfies are simply a foil to self-portraiture, a debased form unable to produce such insight into the nature of identity.

Across popular and academic writing, selfies are repeatedly referred to in the singular—the selfie—rather than as selfies, plural, although the latter use more clearly indicates that selfies involve a multiplicity of practices. A similar trend also appears throughout scholarship on self-portraiture, which often interrogates “the self-portrait” to produce generalized and unified statements about self-portraiture. On the surface, such assessments of “the selfie” or “the self-portrait” appeal to common sense, and they indeed capture something that is true about many images. When Stavans writes that “the selfie is a portal through which we share the handsomest, least frightening side of our self” (5), this description appears to be applicable to the majority of selfies. Nonetheless, this account of selfies is immediately inadequate, something that Stavans effectively admits as he states, “I don’t often come across selfies taken in a state of depression” (5). What is neglected by any such homogenizing account of “the selfie” are the possibilities that can be glimpsed at the margins of conventional practice. And although such possibilities may indeed be marginal, they are possibilities that open up provocative alternative discourses through challenging the very conventions that descriptions of “the selfie”—singular—merely reiterate.

For example, a selfie that performatively stages apathy or depression can carry a significant political charge precisely because this affect is less common in selfie practice, and as a result, like any art work that puts pressure on the conventions of the medium or of a genre, such a selfie can offer rich rewards to the critic. In a selfie posted on Tumblr in 2014 for Trans Day of Visibility, trans activist Zinnia Jones appears listless and uninterested, leaning on her hand with an unfocused gaze, looking off into the distance, past the camera. [FIG 2] The color palette is muted, and instead of her typical, posed facial expression—with tightly pursed lips—the pressure of her hand against her face pulls her mouth sideways. The pose carries resonances of a reluctant child, one who is enduring the photograph rather than posing for it. Captioned “happy trans visibility day or whatever / be visible,” the photo presents Trans Day of Visibility as a demand to which Jones, and those whom she in turn half-heartedly exhorts to “be visible,” must comply, reluctantly and even unwillingly. Visibility becomes a type of compulsory labor, and Jones’ pose combines with the caption, which eschews capitalization or punctuation, to performatively convey her lack of enthusiasm for Trans Day of Visibility and her ambivalence toward its demands. In this way, attending to the possibilities of selfie practices—of “selfies” in the plural—reveals political and theoretical potential that exceeds what any account of “the selfie” might allow. Furthermore, Stavans’ confident descriptions of the ontology of “the selfie” open up possibilities for contestation, not only from the reader, who might mentally supply counter-examples in response to Stavans’ declarations, but potentially from artists, who might find the boundaries Stavans describes to be productive grounds for artistic interventions.

Of course, producing such spaces for contestation is one of the key functions of genre, and great art is often recognizable because it puts pressure on genre conventions. Simultaneously, selfies are indeed characterized by recognizable conventions, and given the extent to which these conventions are overdetermined by race and gender (with young, white, cisgender women as the prototypical selfie-takers), naming these conventions may allow us to recognize how they simultaneously produce and police self-expression. Yet even though defining the boundaries of a genre creates opportunities for creative contestation, Stavans is not describing the boundaries of a form that might later be contested, nor is he outlining a general direction in order to productively discuss alternative possibilities, but he is instead attempting to delimit a category that is always already exploded by works that have antecedently transgressed the definitions that Stavans now articulates. As such, Stavans’ essay is slightly reminiscent of Rosalind Krauss, “Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism” (1976). As Krauss attempts to define the possibilities of the relatively new medium of video, she is ultimately misdirected by her own limited understanding of the technology and her concern about its potential narcissism, with the result that the boundaries of the medium as she describes it are in fact already broken by some of the works she discusses. Nonetheless, even in its inadequacies Krauss’ essay offers a compelling analysis of the temporality of video work, as well as a productive discussion of what it means for a video work to be not only medium specific, but also critical or analytical with regard to its medium. Unfortunately, Stavans does not consider how selfies might critically engage with issues of medium specificity, since the work he examines is largely self-portraiture. Given this, Stavans misses an opportunity to engage with selfies on their own terms, once again relegating selfies to the role of foil to an artistic self-portrait practice.

Though his account of selfies is not necessarily medium-specific, Stavans does attend to technology through a curious term that he introduces but does not develop: cellfie. Provocatively defined as “a cellphone picture but not a shot of myself” (2), the term “cellfie” raises critical questions about the intimate relationship between contemporary people and cellphones, prompting the reader to ask whether—and how—cellphone pictures that are not selfies might nonetheless be a form of self-representation. Given that only 3-5% of the photos posted on Instagram are selfies (Manovich 2014), and given that SnapChat is frequently used to share the sender’s perspective on something rather than an image of their face, “cellfie” could be a productive term for considering self-representation through social media more expansively. After all, celebrity Instagram accounts increasingly privilege images that are not selfies in order to create a fuller “sense of self” than selfies alone might provide (Kafer 2018). However promising, the idea of a “cellfie” is never fully developed in Stavans’ essay, only appearing in a few off-hand references in the opening and concluding chapters. Toward the end, for example, “cellfie” appears amid Stavans’ justification for his method, as he writes that ADÁL’s self-portraits “are not selfies (or cellfies) in the traditional sense, yet they are an immensely imaginative way of looking at the self” (120). Thus, despite the potential richness of “cellfie,” selfies remain relegated to the sidelines of Stavans’ essay on self-portraiture.

This focus on artistic self-portraiture is unfortunate, as Stavans’ interest in ADÁL’s “Go F_ck Your Selfie” could also illuminate one of the more critical features of selfie aesthetics: seriality. By basing his discussion of selfies on a photographic series, Stavans could have interrogated the fact that selfies are rarely if ever singular works, existing instead in relation to multiple potential series—from the series of all selfies, to the series of all selfies by a particular creator, to the many subseries that viewers identify by noticing visual rhymes, compositional patterns, and other similarities, including repetition in the captions and hashtags that accompany these selfies. Furthermore, the boundaries of all of these selfie series are expanded by network technologies, with creators relinquishing complete control over their self-representation when they post selfies online. Online, selfies can easily be repurposed and re-imagined by others, which has consequences for our understanding of the boundaries of “the self,” and which also produces additional, proliferating series. Finally, social media platforms both produce and incentivize serial production and reception of selfies through platform specific network structures, like tags and hashtags.

From their serial nature, to their ties to self-portraiture, to our relationships to our cellphones, I Love My Selfie opens up critical questions about selfies, but in the attempt to address these questions, the volume falls into traps that currently weaken both popular and academic discourse about selfies. Like many others, Stavans is so troubled by the narcissism of selfies that he never talks about specific images, even though close analysis of individual selfies might actually support his characterization of selfies as a symptom of cultural narcissism. Additionally, Stavans’ account of the Narcissus myth is incomplete, given that reproduces the typical absence of Echo. Through highlighting relationality, the figure of Echo can remind us that selfies are also addressed to others, shared and circulated to be seen and engaged, producing face-to-face relationships between people separated by space and time. In underscoring the ways that selfies are relational, Echo’s relation to Narcissus does not merely absolve selfies from the charge of narcissism by revealing that they are about interpersonal relationships, and hence, in some way, redeemed from narcissism’s stigma. Rather, the figure of Echo unveils the self-other interactions at the heart of selfie practices without characterizing these relations as positive—after all, Echo struggled to be heard and understood, ultimately watched her beloved die, and the only thing she was able to do after this experience was to persuade the gods to turn his body into a flower. Read through the full Narcissus myth, selfies are in fact about much more than the solipsistic engagement with one’s own image. Instead, their multiple uses and forms—vernacular as well as artistic—stage complicated networks of recognition, misrecognition, mimicry, mirroring, invitation and response. We can begin to better understand this full complexity if we turn a little to the side, and seek out not only the youth enamored of his reflection in the pool but also the nymph whose active participation turns this static moment of self-absorption into a narrative of encounter.

Bibliography

#artselfie. 2014. Paris: Jean Boîte Éditions.

ARC Magazine. 2014. “Adál Maldonado presents ‘Go Fuck Your Selfie . . .’ at Roberto Paradise Gallery. 8 October, http://arcthemagazine.com/arc/2014/10/adal-maldonado-presents-go-fuck-your-selfie-at-roberto-paradise-gallery.

Barron, Benjamin. 2014. “richard prince, audrey wollen, and the sad girl theory,” i-D Blog, 12 November, https://i-d.vice.com/en_us/article/richard-prince-audrey-wollen-and-the-sad-girl-theory.

Barthes, Roland. 1984. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Richard Howard, trans. London: Fontana Paperbacks.

Bellinger, Matthew. 2015. “Bae Caught Me Tweetin’: On Selfies, Memes, and David Cameron.” International Journal of Communication 9, 1806–1817.

Burns, Anne. 2015. “Self(ie)-Discipline: Social Regulation as Enacted Through the Discussion of Photographic Practice.” International Journal of Communication 9, 1716–1733.

Capricious. 2014. “Anti-selfies and bondage furniture.” Dazed Digital, 1 August, http://www.dazeddigital.com/photography/article/21087/1/anti-selfies-and-bondage-furniture.

Droitcour, Brian. 2012. “Let Us See You See You.” Discover: The DIS Blog, 3 December, http://dismagazine.com/blog/38139/let-us-see-you-see-you.

Drucker, Zackary and Rhys Ernst. 2016. Relationship. New York: Prestel.

Farago, Jason. 2017. “Cindy Sherman Takes Selfies (as Only She Could) on Instagram,” The New York Times, 6 August, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/06/arts/design/cindy-sherman-instagram.html.

Frosh, Paul. 2015. “The Gestural Image: The Selfie, Photography Theory, and Kinesthetic Sociability.” International Journal of Communication 9, 1607-1628.

Goldberg, Greg. 2017. “Through the Looking Glass: The Queer Narcissism of Selfies.” Social Media + Society.

Gunter, Joel. 2017. “’Yolocaust’: How should you behave at a Holocaust memorial?” BBC News, 20 January, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-38675835.

Haggerty, K. and R. V. Ericson. 2000. “The Surveillant Assemblage.” British Journal of Sociology 51(4).

Jones, Abigail. 2013. “The Selfie as Art? One Gallery Thinks So.” Newsweek, 17 October, http://www.newsweek.com/selfie-art-one-gallery-thinks-so-445.

Kafer, Gary. 2018 (forthcoming). “Believing is Being: Selfies, Referentiality, and the Politics of Belief in Amalia Ulman’s Instagram.” The Self-Portrait in the Moving Image. L. Busetta, M. Monteiro, and M. Tinel-Temple, eds. Oxford: Peter Lang Publishing.

Kinney, Tulsa. 2014. “Trading Places: Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst at the Whitney Biennial,” Artillery Magazine, 4 March, http://artillerymag.com/zackary-drucker-and-rhys-ernst.

Krauss, Rosalind. 1976. “Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism.” October, 51–64.

Latimer, Tirza True. 2006. “Acting Out: Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore,” Don’t Kiss Me: The Art of Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, Louise Downie, ed. New York: Aperture Foundation.

Manovich, Lev. 2014. SelfieCity.net.

Parkinson, Hannah Jane. 2015. “Instagram, an artist and the $100,000 selfies – appropriation in the digital age.” The Guardian, 18 July, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/jul/18/instagram-artist-richard-prince-selfies.

Senft, Theresa., & Baym, Nancy. 2015. “What Does the Selfie Say? Investigating a Global Phenomenon.” International Journal of Communication 9, 1588-1606.

Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. 1999. “The Equivocal ‘I’: Claude Cahun as Lesbian Subject.” Inverted Odysseys: Claude Cahun, Maya Deren, and Cindy Sherman. Shelley Rice, ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Stavans, Ilan and Adál Maldonado. 2017. I Love My Selfie. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Ilan Stavans, I Love My Selfie (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017)

Ilan Stavans, I Love My Selfie (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017)