by Arne De Boever

1/

Becky Kolsrud does not paint nudes.

In “Bather With Red Shoes” (2018), for example, the red parts—the shoes, the nailpolish, and the lipstick—stand out too clearly for anyone to comfortably call the painting a nude. If the bather from the painting’s title is possibly nude underneath the water, it should be noted that the painting pointedly does not tell us whether this is so. Instead, dark blue water, which is supposed to be transparent, veils the bather’s body and turns the painting into something else—not a nude. In fact, the water veils the body to such an extent that one begins to doubt whether there is an actual body present, underneath the water. The head, arms, and legs feel dismembered, not quite connected into a larger (underwater) whole. For further proof, just consider “Floating Head” (2018), which intensifies this feeling: there might not be a body, let alone a naked body, under the water. This might just be a floating head.

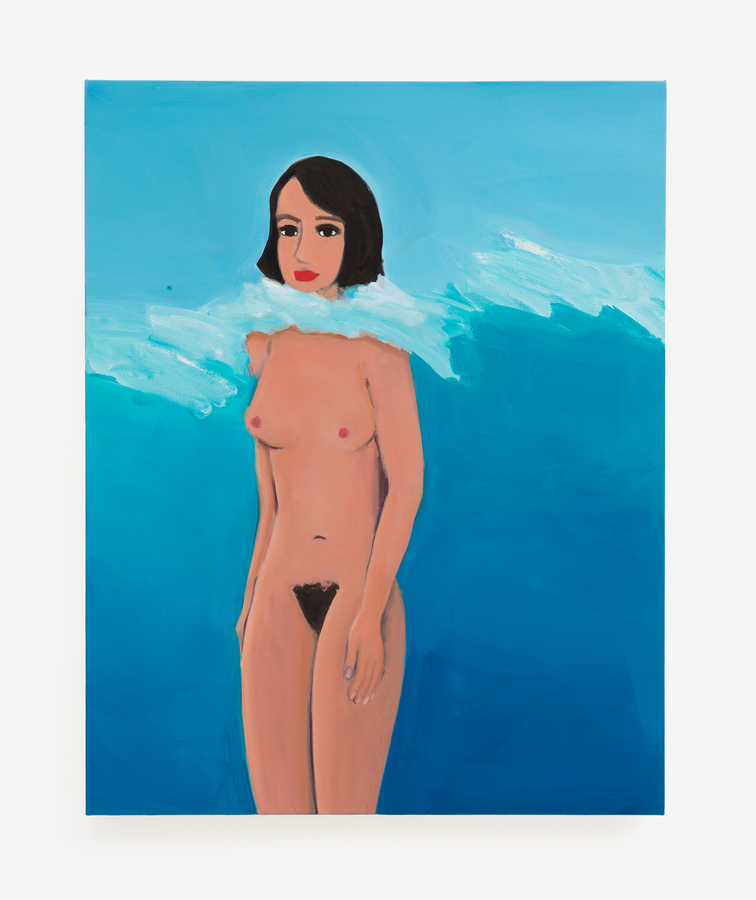

This point about nudity is made even more starkly in “Resting Bather” (2018), where light blue water confronts the viewer like a block: opaque, material, it appears like something solid onto which the bather—possibly nude, but again there is no way to tell—rests her arms and her head. This water is so hard, the painting seems to say, that you can lean on it. Once again, there is no nudity here. Or if there is, it is not the nudity of the bather. I would propose, instead, that “Resting Bather” shows us naked painting. What else to call the vertical, rectangular slate of blue that covers most of the painting? It is naked painting, rather than a painting of a nude.

“The Three Graces” (2018) bathes in the same light blue of “Resting Bather”, but this time the blue actually marks a piece of clothing, a kind of hooded cloak for triplets (if such a thing exists). Of course by now, one doesn’t so much see clothing but water, as if “The Three Graces” are bathing even if they are clothed. Covered when one is supposed to be naked, as in “Bather With Red Shoes” and “Resting Bather”, and naked when one is supposed to be covered, as in “The Three Graces”, Kolsrud’s painting seems to play with nudity and the painting of nudity rather than to deliver it, offering us a kind of naked painting instead.

This is so even in a work that comes closest to being identifiably a nude. Titled “Nude in Snow” (2018), it shows a naked female body that appears to be bathing in what one imagines to be ice-cold water. The body is naked, and visibly naked in the water, but even here it is partly hidden from view by snow, “in snow”, as the painting’s title puts it. Due to how the snow has been represented—as crude dots of white applied across the painting’s canvas—the viewer once again gets the sense that they are not so much seeing a nude, or even a nude in snow, but a nude in paint or a kind of naked painting. If this painting comes closest to showing an actual nude (even if it is a nude that is partially covered), it is also a painting that through its crudely painted dots of snow shows painting itself, and shows it quite nakedly. It is probably worth noticing that the snow, or the paint, is in the foreground here. The nude in the background may in fact be a distraction. The painting shows, rather, painting itself. Naked.

Kolsrud does not paint nudes, then, but she does paint naked painting.

2/

In 2017, just one year prior to the already discussed works, Kolsrud titles one painting “Allegory of a Nude II”. Not quite a nude, but an allegory of a nude—a work in which, if we follow Walter Benjamin’s understanding of allegory, the nude would lie in ruins and the passage from nudity to its allegory would not quite be accomplished. Light blue water appears to swirl up here like Marilyn Monroe’s dress in that famous photograph, billowing around a female figure’s body like a piece of cloth in the wind (but note the difference between this female figure and Monroe—I will come back to the figure’s expressionless face later on). Supposedly transparent—and a trace of its transparency indeed remains; note the patch of water covering the figure’s upper right thigh–, water already appears opaque and material here as it does in the later paintings, even if it does not have the block-like feeling of solidity yet (as in “Resting Bather”). “Bather in Red” (2017) anticipates “Bather With Red Shoes”, but here too Kolsrud hasn’t gone quite as far yet in her materialization of painting: some of the bather’s body still shines through, more so in any case than in the work from 2018.

Water covers the body in “Clear Boot Diptych” as well, its opacity and materiality emphasized not only by the contrast between the light blue water in the canvas on the left and the dark blue water in the canvas on the right but also by the fact that the one item of clothing in the painting, the one thing that is supposed to cover up, is transparent or “clear”. One can see through it. The foot thus becomes strangely naked, even if it is covered—perhaps even more so than those naked parts of the body that are visible in the painting (the legs, the arms, the head; again, they feel dismembered, as if the cut in the middle of the painting were the sign of one of those magic tricks in which a woman’s body is cut in half and then miraculously restored to a whole afterwards). When the boot returns in “Underwater Boot” (2017), it is in a painting in which bodies and faces are almost entirely hidden from view by stormy waters. The painting gives the nude, the traditional nude, the boot, to speak in a kind of half-rhyme: it puts the naked body under water—and the underwater boot does look like it’s kicking, in the painting—and all it shows is the water, crudely painted, naked, not as water but as paint. “Underwater Boot” is, in its simplicity, over-painted. It gives nudity the boot in favor of naked painting.

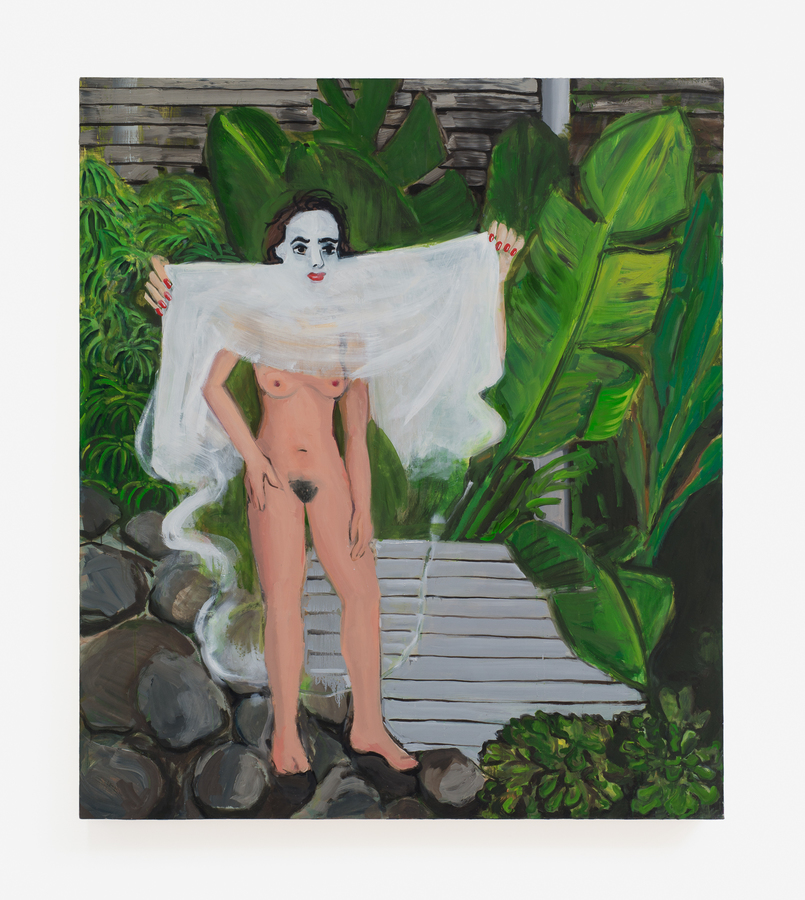

“Allegory of a Nude I” and “Covered Nude” make this point in a more complex way, a complexity that—in my view—the more recent work overcomes in favor of a simpler, more unapologetically straightforward painterly statement. Here, female figures are pictured to hold up, as if to show the viewer, what appear to be pieces of cloth—a shawl, perhaps, in “Allegory”, or a towel (in “Covered”). But those pieces of cloth are held up like a canvas that in the former work appears to be transparent but is obviously painted, and in the latter work appears to reveal the shapes of the naked body underneath—but the shapes obviously do not match the hidden body. In “Allegory”, and here again we can follow Benjamin, the passage from one level of reality to the other is not quite established: it’s either the naked body that is painted onto the shawl or the shawl that has been painted onto the naked body. The painting does not quite let us decide. In “Covered”, it seems quite clear that the towel was painted: light blue paint can be seen dripping off the towel in the lower, dark blue part of the painting.

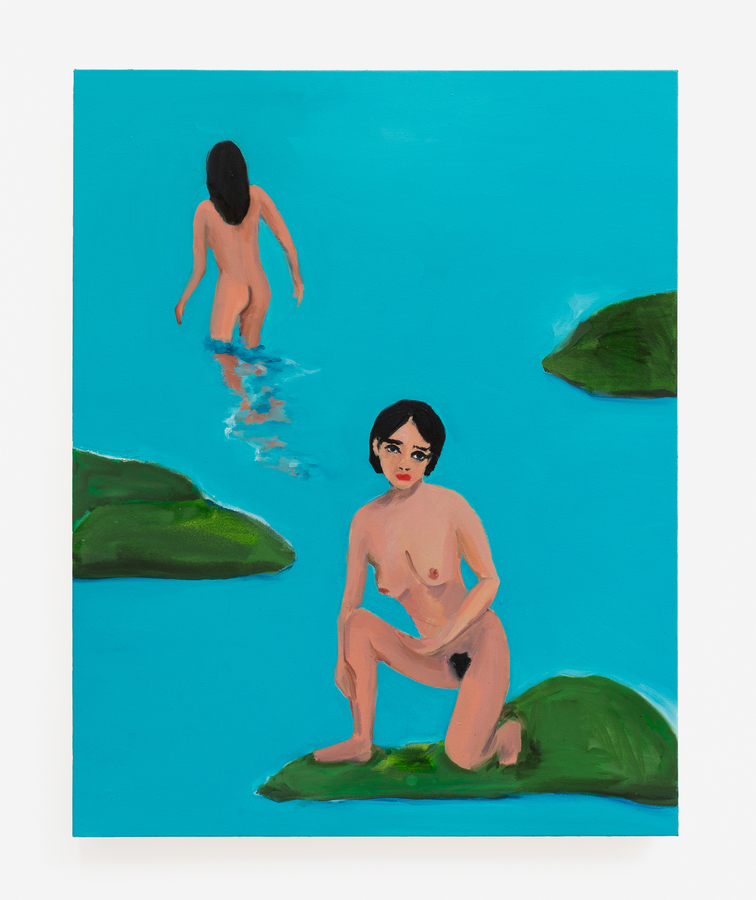

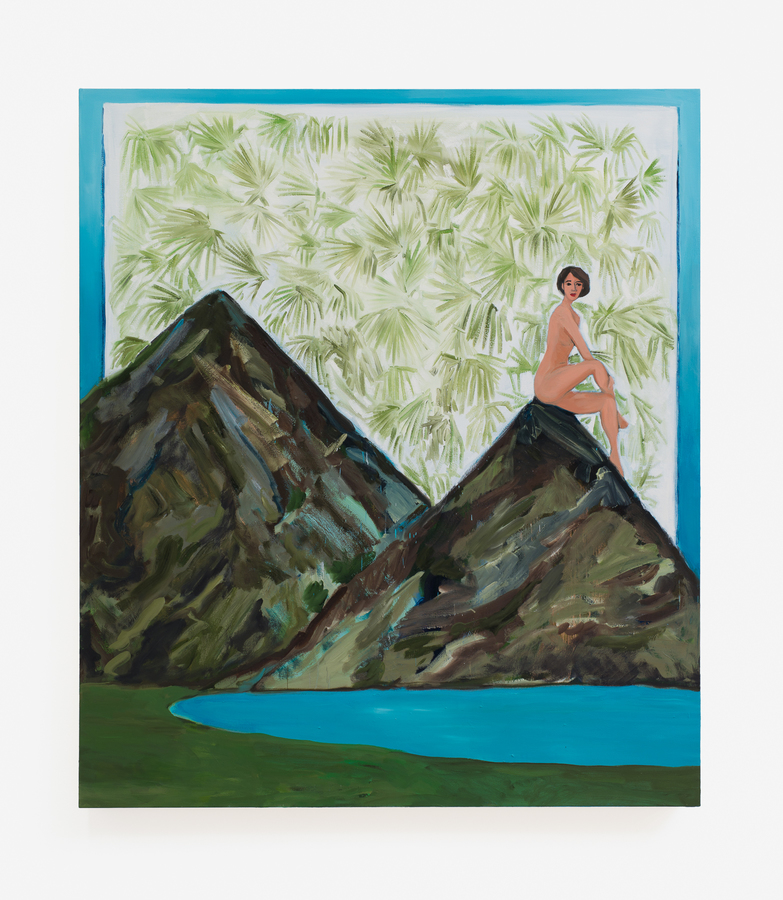

“Three Women” is the work from 2017 that is the farthest ahead in this series, very close already to works like “Bather With Red Shoes” or “Resting Bather” from just a year later (and anticipating as well, obviously, the figure of three that will appear in “Three Graces” as well and that I will follow here in the structure of my text). “Lady Underwater” is, within this narrative, a transitional work—it paints water as transparent, as not covering the naked body. It stands in between the more traditional nudes from 2017—“Nude Ascending”, “Bathers with Backdrop”–which need to be read in opposition to the non-nudes from 2018. I read “Double Mountain/Backdrop” also as a transitional piece: removing the traditional nude from the center of attention, the work foregrounds the crudely painted double mountain—and doubled, for those viewers for whom a single mountain wouldn’t have quite gotten the message across—, an emphatic brushstroke that is further emphasized by the elaborately painted, wallpaper “backdrop” from the painting’s title. If Kolsrud moves away from the nude here to the foregrounding of painting itself, but at the cost of painting the nude, the brilliance of the more recent work is that it manages to combine the two and keep the nude in the center while at the same time offering us naked painting. It is a remarkably fresh, unapologetic embrace of painting and at the same time an intervention (by a woman painter, one might note) in art history’s long and in many ways problematic history of painting female nudes (mostly done by men, one might further note).

In an article titled “Nudity”,[1] which starts with a discussion of a performance by Vanessa Beecroft, the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben criticizes how in Western thought “nudity” has always been marked by a “weighty theological legacy” (65). It is due to this legacy that nudity has always only been what he describes as “the obscure and ungraspable presupposition of clothing”, something that only appears when “clothes … are taken off” (65). Nudity, within such a theological optic, is nothing but the “shadow” of clothing (65). Agamben’s project in his text is to “completely liberate nudity from the patterns of thought that permit us to conceive of it solely in a privative and instantaneous manner”, and therefore the focus of such a project will have to be “to comprehend and neutralize the apparatus that produced this separation” (66) between nudity and clothing. He considers such a project to be realized in Beecroft’s performance, in which “a hundred nude women (though in truth, they were wearing transparent pantyhose [and in some instances also shoes, as he points out later]) stood, immobile and indifferent, exposed to the gaze of the visitors who, after having waited on a long line, entered into a vast space on the museum’s ground floor” (55). There are obviously naked—or sort of naked—bodies here, but Agamben’s perhaps surprising conclusion at first (which I sought to echo earlier on) is that in Beecroft’s performance, nudity did not take place: instead, everything was marked by that theological legacy that renders nudity into a presupposition of clothing.

And yet, Agamben finds in the performance something that might also neutralize this legacy, and more broadly the separation between nudity and clothing, and that is the indifferent and expressionless faces of the women in the performance. He argues, towards the complicated end of his text, that these faces practice a “nihilism of beauty” (88) that shatters this theological machine. It is the beautiful face that marks this machine’s limit and causes it to stop by “exhibiting its nudity with a smile” and saying: “You wanted to see my secret? You wanted to clarify my envelopment? Then look right at it, if you can. Look at this absolute, unforgivable absence of secrets!” (90) Nudity can in this sense quite simply be summed up as: “haecce! there is nothing other than this” (90). Agamben goes on to describe the effect of such a stop as a disenchantment that is both “miserable” and “sublime” due to how it moves “beyond all mystery and all meaning” (90). There is no mystery to dispel, no meaning to uncover, no secret to be revealed. In nudity, all there is is the beautiful face—and by “beautiful” he is not proposing an aesthetic judgment but marking precisely the indifferent appearance that is being described. It is, in this way, the beautiful face that frees nudity from its theological weight and lets it be, quite simply, naked.[2]

If art history and the ways in which it has shown nudity, often through the veiled, partly unveiled, or fully unveiled bodies of women, is evidently burdened also by the theological weight that Agamben describes, then Kolsrud’s paintings can be read as participating in Agamben’s project. It seems clear that Kolsrud is aware of how nudity exists in the shadow of clothing—indeed, her paintings stage reversals of nudity and clothing so that those figures who are naked in her work (I am thinking of the bathers) appear to be fully covered whereas those figures or elements that are supposed to be clothed—the “Three Graces” for example; the foot in the boot—appear to be naked. Such reversals recall the kinds of reversals that Agamben discusses in relation to Beecroft’s work, where he references paintings of the Last Judgment, for example, in which the angels are clothed and those awaiting judgment are naked, in an exact reversal of the situation in Beecroft’s performance where the performing women/angels appear to be naked and the spectators awaiting judgment appear fully clothed, having just walked in from the cold Berlin streets. Even the faces of the figures in Kolsrud’s paintings recall those expressionless faces that Agamben writes about, where a kind of halt to the infinite, theological striptease of denudation is enforced.

But Kolsrud’s brilliant contribution as a painter is that she turns painting itself into an ally in this context: indeed, I would argue that the possibility of calling a halt to the theological logic of denudation is at least equally shared between her figures’ expressionless faces (I will leave it in the middle whether they are beautiful or not), and possibly even presented first and foremost by painting itself—by the fact that what her paintings ultimately show us is not a nude, but naked painting. In this way, Kolsrud ultimately does not need Agamben’s “beautiful faces” (and even less the “choirboy’s ‘white’ voice” which makes an odd appearance in the closing line of Agamben’s text) to block the theological machine. It is painting, rather–naked painting–that steps in here to, in a kind of miserable but simultaneously sublime way, declare the absence of all secrets, the void of meaning. There is nothing to denude here, Kolsrud’s paintings seem to say. Painting—naked painting–marks an end to denudation. In this sense, painting, for Kolsrud—naked painting–becomes a kind of weapon against the ways in which human beings, but in particular women, have been violently caught up in the painting of nudity.

3/

And one can trace this argument even further back in Kolsrud’s work.

For if Kolsrud, some time in 2017, shifts to painting nudes (thereby situating herself critically in an art history of the nude), I am inclined to read this shift as a logical development from the faces or rather heads she was still painting during that same year. These need to be read, with some of Kolsrud’s even earlier work (from 2016), in relation to the genre of the portrait that, like the nude, makes up a celebrated art historical topos, this time perhaps with men featured more frequently in portraits than women. I write heads, and not faces, because that is what Kolsrud calls them: they appear like decapitated, slightly disfigured, women’s heads (painted on what looks like a painter’s palette), leaning against each other on a wooden beam mounted against the gallery wall, in one case. In another, different set-up they don’t lean but hang, separate from each other, on the gallery wall. One of those latter faces, or rather heads, appears to be doubled (a doubling to which I will come back later on); another has the shape of a face, or rather a head, but is not recognizably a face—it is really just colors. A head.

Kolsrud’s preference for the word “head” rather than “face” recalls, whether intentionally or not, Gilles Deleuze’s writing about Francis Bacon.[3] In his book on Bacon titled “Logic of Sensation”, Deleuze argues that Bacon, “as a portraitist … is a painter of heads, not faces, and there is a great difference between the two” (19). Whereas the face, and in particular the traditionally beautiful face, refers to a “spatializing material structure”, a “structured, spatial organization” that for example the bones also bring to the body, the head is the culmination of what Deleuze describes as “the body as figure”, and more precisely “the material of the figure” (19). As such, the face “conceals the head”, and Bacon’s project as a portraitist was precisely to “dismantle the face, to rediscover the head or make it emerge from beneath the face” (19). To do so means to open up a “zone of indiscernibility or undecidability between man and animal”, Deleuze suggests, and he ties this particular zone back to the body, but specifically the body “insofar as it is flesh or meat” (20). Here, he has in mind something that is no longer “supported by the bones”, a state where “the flesh ceases to cover the bones, when the two exist for each other, but on each on its own terms: the bone as the material structure of the body, the flesh as the bodily material of the Figure” (20). Before one reads such materiality in a vulgar way, Deleuze is quick to emphasize in his text that it does not lack “spirit”: the head is in fact “a spirit in bodily form, a corporeal and vital breath, an animal spirit. It is the animal spirit of man: a pig-spirit, a buffalo-spirit, a dog-spirit, a bat-spirit…” (19). It is partly for this reason, it seems, that Deleuze can suggest that Bacon is a butcher, but a butcher who “goes to the butcher shop as if it were a church, with the meat as the crucified victim” (21-22). “Bacon is a religious painter only in butcher shops” (22), he writes.

Kolsrud’s heads share something with this Deleuzian reading of Bacon and with Bacon’s project as a portrait painter in that they participate in the painterly brushing out of the clearly identifiable features of the face. But Kolsrud is not quite as universalist as Deleuze, who in his insistence on the head appears to gloss over the fact that Bacon is painting mostly men. Kolsrud, on the other hand, is painting women. She may be painting women’s heads rather than faces, but they are still, in almost all instances, identifiably the heads of women. Perhaps something important is being said here about Deleuze’s head and meat and the limits it poses for art historical analysis, or even the analysis of our lived experiences in the world, in the sense that it does not account for sex or gender, or also race or class. The head and meat are beyond those, for better or for worse. Deleuze is post-identity.

As a materialist painter, a painter who foregrounds the materiality of painting, Kolsrud also retains something of what Deleuze calls “the spiritual”. Going back the most recent work from 2018, one should pay attention to scale specifically in terms of how the female bodies are situated in the landscape: it appears as if those bodies are bathing in large bodies of water—lakes rather than swim-holes—and thus the bodies appear unnaturally large compared to the landscapes in which they are situated. This appears to partly cast Kolsrud’s female figures as spiritual or divine, bathing in a large body of water over which they don’t so much rule but with which they become one. If I hesitate to fully associate these figures with “Mother Nature” or “Mother Earth” it is not only because women have suffered this association for long enough already (and for better and for worse) but also because there are elements—shoes, nailpolish, lipstick—that also prevent such a full identification. The female bodies flow into the landscape and the landscape into the female bodies in the paintings, but Kolsrud’s line nevertheless remains quite distinct, marking a clear limit between the landscape and the female body, and thus at the very least drawing such an association in question. Still, there is spirituality in Kolsrud’s material paintings.

When considering Bacon’s intervention in the history of portrait painting, the politics of it appears to be clear: Bacon’s heads mess with the practice of identification that the portrait participates in, as is evident for example in the portrait’s legacy in the passport photograph. Although a trace of identification remains in Bacon’s heads—they are, for example, all men’s heads, something that Deleuze does not insist on enough—it is clear that Bacon’s heads are trying to go beyond identification, to leave identification behind (this is what Deleuze refers to as becoming-animal, becoming-woman, becoming-vegetable, and so on). Kolsrud, too, seems to have identification and its political history in mind.

When she paints portraits in 2016, she paints “Double Portraits”, in other words: identifications that, because they are always already split, tend to make identification (which operates according to the logic of the one) impossible. A face becomes two, becomes a head, and even a moon (“Double Portrait (Moon)”). In another double portrait, the eyes are painted over and the focus appears to be on the hands holding what is an image of a face (“Double Portrait (Pink Hands)”). This last element in the painting anticipates those works from 2017 in which female figures are shown to hold up a shawl or a towel for the viewer. In yet another of her double portraits, one of the portrayed faces is shown to be partially hiding behind its other (“Double Portrait (Hiding)”). Clearly, all of these works, as portraits, frustrate the process of identification and in that sense are part of the broader realm of what Deleuze has theorized as Bacon’s heads.

That this frustration might be partly political, and intentionally political, is revealed by Kolsrud’s other paintings from 2016, in which eyes, heads, and full bodies are largely blocked from view by what the painter explicitly calls “Gates” and “Security Gates”.

These “gated” paintings strike me as overpainted, even more so than “Underwater Boot”, in that their gated representations ultimately show nothing more than paint, than painting itself—and this in spite of the fact that they create the desire to see through the gate. The gates function, in other words, as a kind of clothing: they set up the presupposition of nudity behind or underneath the clothing, but Kolsrud’s painting blocks that search for nudity which (once again) is particularly intense around the bodies of women. The dynamic of denudation stops at the gated painting, at the painting’s gate which is a kind of security gate not so much in that it would imprison the eyes, heads, or full bodies behind it. The temptation then would be to conclude that instead, the painting allows those eyes, heads, and full bodies to simply be—and that may certainly be part of their point, a point that Agamben makes as well about “the beautiful face”. But I have suggested that Kolsrud’s painting actually goes further and does not so much allow the eyes, heads, and full bodies to simply be—and to simply be naked—but foregrounds painting and ultimately allows painting to simply be. The search for nudity is not so much blocked here by the naked body, but by painting itself. Painting, in its spiritual materiality, brings that search to a halt and forces the viewer to rest with its surface, in the absence of secrets and the void of meaning. In that sense, one can call it naked—but naked only insofar as that nudity is a clothing liberated from anything that is supposed to be hiding underneath.

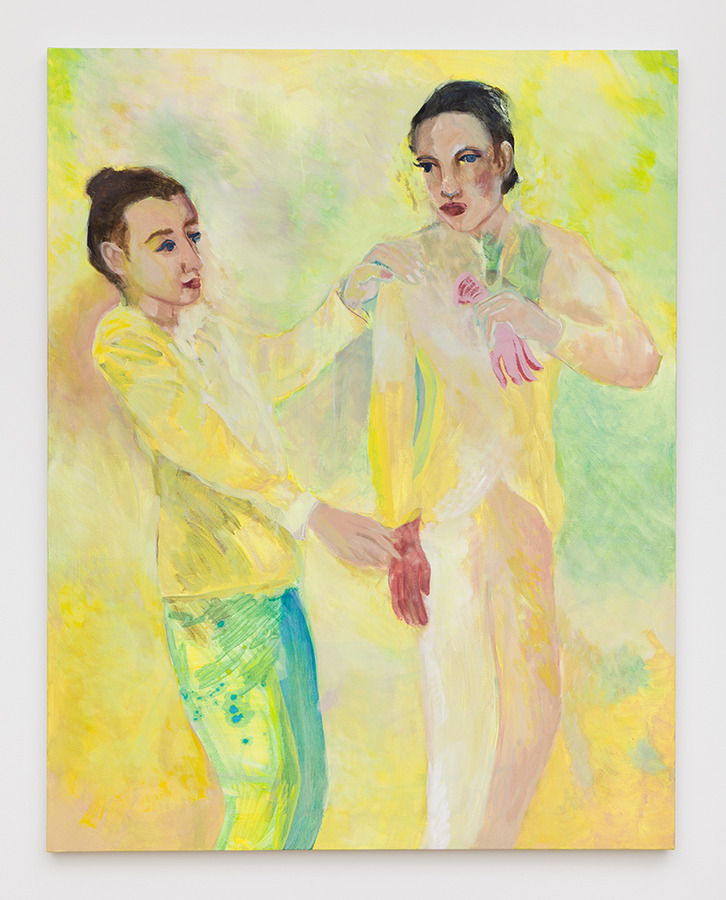

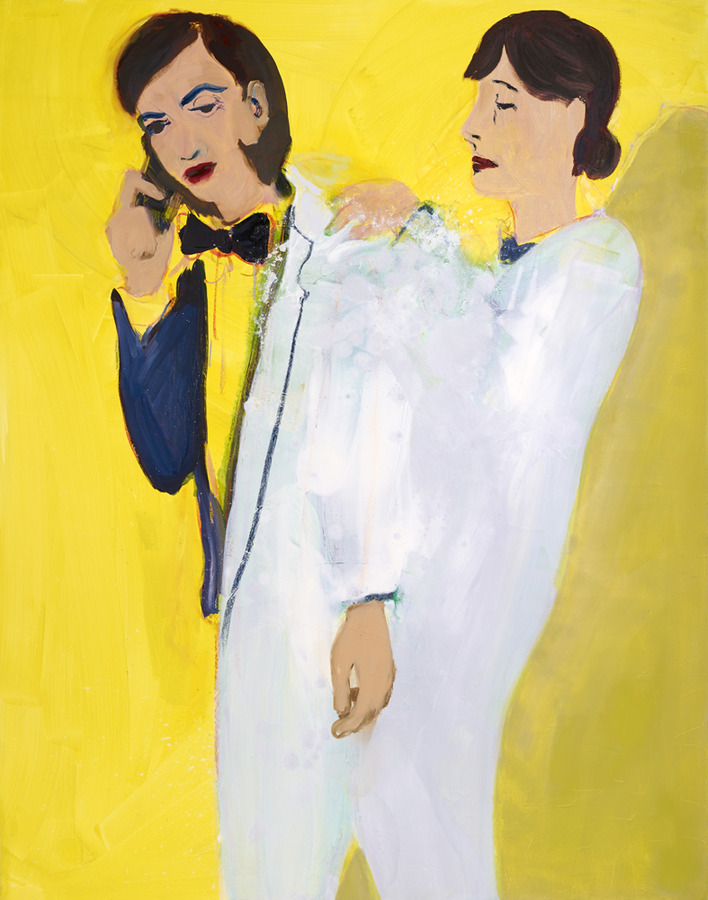

It shouldn’t come as a surprise, finally, that some of Kolsrud’s even earlier work from 2014, focuses on clothing. It shows faces, or rather heads, as part of clothed bodies, or bodies in the process of being clothed (“The Fitting”; “We Alter and Repair (Shoulders)”; “We Alter and Repair (Back)”).

It shows security gates, which are now revealed to be the fronts of sewing stores (“Storefront”, two paintings), where clothes get altered and repaired (“We Alter and Repair”).

Anticipating the later portrait work, there is a “Seamstress” and a “Woman with Sewing Machine”, two figures that must, following the larger trajectory that I have laid out, be read not only as such but also in association with the painter herself who treats canvas and paint as clothing.

Thereby, Kolsrud paradoxically puts on display a nudity beyond denudation, a simple nudity that is not so much the nudity of the naked body but the nudity of naked painting, of a painting that materially and spiritually calls a halt to the theological and art historical striptease in which, for so many centuries, nudity has remained caught up. It is a nudity that, in that sense, paradoxically is its own clothing—and nothing more.[4]

This text was written on the occasion of the L.A. Dreams exhibition at CFHill gallery in Stockholm in Spring 2018, in which Becky Kolsrud’s paintings were included. Many of the images featured here were lifted from the website of JTT gallery in New York. I would also like to thank the artist for generously sharing images of her most recent work with me while I was preparing this text.

Notes

[1] Agamben, Giorgio. “Nudity”. In: Agamben, Nudities. Trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011. 55-90. Henceforth cited parenthetically in my text.

[2] Agamben had made this point previously in: “In Praise of Profanation”. In: Agamben, Profanations. Trans. Jeff Fort. New York: Zone Books, 2007. 73-92. Even before then, this argument about the face can also be found in: Agamben, Giorgio. “The Face”. In: Agamben, Means Without End: Notes on Politics. Trans. Vincenzo Binetti and Cesare Casarino. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000. 91-100.

[3] Deleuze, Gilles. Francis Bacon: Logic of Sensation. Trans. Daniel W. Smith. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002. Henceforth cited parenthetically in my text.

[4] In that sense, Kolsrud provides an answer to the question about that most mysterious of terms in Agamben’s work, form-of-life, which is to dismantle the vicious dynamic between zoe (the simple fact of living) and bios (form of life) that is analyzed in great detail in Agamben’s Homo Sacer project—but also in other texts that are not explicitly a part of that project, such as “Nudity”. I cannot lay this out in detail, but readers of Agamben will understand.

by Daniel Villegas Vélez

by Daniel Villegas Vélez