by Tom Eyers

C. Levine, Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015.

This essay has been peer-reviewed by the boundary 2 editorial collective.

In his Literature and Revolution of 1924, Trotsky commented of the then-influential Russian formalism as follows: “The formalists are followers of St. John. They believe that ‘In the beginning was the Word’. But we believe that in the beginning was the deed. The word followed as its phonetic shadow”.[1] A more direct statement of the materialist suspicion of formalist abstraction it would be hard to find. For their part, the individual formalists held significantly different attitudes towards their Marxist rivals, although the following from Viktor Shklovsky reveals in all of its enjoyable snark the contempt that threatened always to leak to the surface: “We are not Marxists, but, if we ever happen to be in need of this utensil…we will not eat with our hands out of sheer spite”.[2] If one group charged the other with a bloodless idealism, the other was as likely to level accusations of vulgar economic reductionism, to be resorted to only when every other method at the feast had been picked over.

Needless to say, debates as to the relative merits of formalist approaches to literature in comparison to those apparently more attuned to the social and political are hardly new. My decision to begin this essay with Russian formalism was more or less arbitrary; one could, after all, go as far back as Aristotle’s Poetics for the putative origin of what has threatened to become an ossified and intractable stalemate; a gloss of the Lukács-Brecht debates would have been just as apropos. Since 2000, questions of form have reappeared with some urgency in literary studies. By 2007, the ‘new formalism’ was enough of a phenomenon that it merited a comprehensive survey by Marjorie Levinson, published in PMLA.[3] Moreover, recent calls for a return to form have often been couched in a critique of prevailing historicisms. Since the dawn of the ‘new historicism’, itself a reaction against the hyper-formalist attention to paradox that defined deconstruction, obscure parliamentary debates have been as likely to be invoked as explanatory of a text as its use of metaphor or metonymy.

But are our options truly so limited? Hasn’t the very best of literary theory always combined an attention to trope and figure with a concern for social, political and historical pressures? Perhaps, although there is always a danger that such a surface eclecticism may shade into an alibi for the avoidance of any confrontation with what is specific about literary form, as compared to other forms, as much as it may also encourage a swerve away from asking precisely how, and why, literature is impacted by, and impacts upon, processes that are nonetheless irreducible to it. To say that literature is always-already political surely makes sense on one level, insofar as no instance of cultural production escapes being enabled or disabled by prevailing historical, social and political conditions. But from a different angle of approach, one that I’ll be concerned to flesh out a little in what follows, this apparent commensurability between literary and social forms may well be the result of a prior incommensurability, one that exists as a condition of possibility for the very distinctiveness of the forms in question, no matter how much they be said to intertwine all the way down. To preview, it is these latter, knotty, theoretical problems that the book under review doesn’t quite get to grips with, as deeply impressive as it otherwise is.

There are many different ways in which one might go about rethinking form in literature, not least because there are numerous distinct ways in which ‘form’ itself might be defined. Despite it being a general category, and heedless of its long and storied philosophical history, ‘form’ in literary studies most often names particular devices: meter, allegory, metaphor, metonymy, voice, diction, and so on. This nominalism results, despite itself, in the production of the most general of general categories, namely ‘literature’ itself, for despite the reigning historicisms of the last few decades, it is still the relative density of a text’s tropic texture that allows us to distinguish it as literary or non-literary in the first place, and this despite the numerous indeterminate cases that one may invoke. Of course, to propose any definition of form is to inevitably produce an account of content, and the resulting dichotomy threatens, in its inflexibility, to obscure as much as it enlightens. As Wellek and Warren had it, way back in the 1940s, “’Content’ and ‘form’ are terms used in too widely different senses for them to be, merely juxtaposed, helpful; indeed, even after careful definition, they too simply dichotomize the work of art. A modern analysis of the work of art has to begin with more complex questions: its mode of existence, its system of strata”.[4]

It is questionable whether the problem is solved by the mere replacement of one set of ambiguous terms – form, content – with another – ‘system’, ‘strata’. And the problems multiply when one seeks a positive, rather than simply negative, purpose for the reiteration of formalist dilemmas. The negative motives are easy enough to list: most importantly, history, instead of being a question to be answered, has threatened to become a catch-all explanans to be passively assumed, bringing with it an obfuscation of what makes literature, literature. But what of positive motives? What is to be gained by foregrounding form once again, if indeed we can agree on a definition of what ‘form’ is? An avenue to be staunchly avoided, I think, is what could be characterized as a ‘retreat’ into form. Such an impulse, while masquerading as positive – ‘form is where the literary in literature is to be found, and thus it should be the focus of our attention’ – is in fact just one more jerk of the knee, in this instance in response to the supposed politicization of the critical humanities in the last few decades.

Such a politicization, itself concomitant with the rise of the various historicisms, is to the contrary to be celebrated, not least for giving us a much more capacious sense of the varieties of literatures, and the uneven contexts of their production and reception. In some of the ‘new formalist’ literature[5], it is argued that Marxist criticism in particular has been deaf to form. And yet, anyone who were to seriously study the formalist-Marxist debates in Russia referenced at the outset, or who were to conduct even a cursory reading of the back and forth between Brecht, Lukács, Benjamin and Adorno, who were to immerse themselves in the brief efflorescence of Althusserian criticism, or who were to read just one of Fredric Jameson’s rapidly proliferating books, would find extraordinarily subtle dialectical articulations of form and history, form and politics, form understood to be always-already embedded in multiple precincts of influence, the social awkwardly intercalated with the literary, the historical itself, in its Althusserian reformulation, an already-formal arrangement of overdetermined and contingent boundaries and limits. There are significant drawbacks to all of these approaches, for sure, but a convenient forgetting of their fecundity should hardly serve us well.

One way forward, one already to be found in nascent form in some of Althusser’s scattered reflections on art and literature[6], would be to insist not only on the historicization of form, but also on the formalization of history. This would involve a simultaneous attention to how particular formal devices have their own, politically-inflected histories – think, for instance, of the political stakes of the debates over the alexandrine in French poetics in the late nineteenth century[7] – and a scrutiny of how those devices performed their own reconfiguration of those historical determinants, making of what might otherwise have been a one-way direction of causal travel an unpredictable and always-singular feedback loop, one that results not in the ‘democratic’ mirage of social and literary forms singing in harmony, but rather in a kind of productive, material dissonance. Sticking with our example from French prosody, consider how, in his ‘Crisis of Verse’, Mallarmé was able to diagnose the apparent stubbornness of French traditionalists’ retaining aspects of the standard sonnet form, while sneaking in aspects of the poetical freedom pursued across the Channel, as itself a kind of radicalism, exploiting the electric tension thus conducted on the page between Racinean restrictions and vers libre.[8] What Mallarmé doesn’t say, but what our putative method might be able to pick up on, is how such impure admixtures of form are themselves capable of arguing for newly sophisticated and ultimately extra-poetic historical and political positions. In this instance, we might speculate that such a commitment to poetic unevenness in the face of the call to absolute experimentation, far from being an instance of Anglophone-like moderation and compromise, was in fact the sign of a much-needed skepticism as to the ability of the lifting of literary restrictions to immediately conjure equivalent freedoms at the level of the social or political; Wordsworth, it could be argued, reached a similar conclusion by the end of his career, albeit with rather more quietist implications, and much, of course, to the dismay of the second generation of British romantics.[9] In some of what follows, I’ll argue that one particular kind of poetic formality, the curious constructedness of poetry, its habits of self-reference, rather than resulting simply in solipsism, produces instead the very transport of poetic form outwards into the nonetheless distinct domains of the social and political.

Caroline Levine plots a different course, albeit with comparable motives, one widely deserving of praise, if also some not insubstantial criticism. I will begin with a treatment of the theoretical opening pages of the book in question, before turning to her case studies in order to see her method in action. At the very opening of her highly suggestive Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network, Levine lays out what a standard formalist analysis of Jane Eyre might look like. A critic embarking on such a reading would attend to “literary techniques both large and small, including the marriage plot, first-person narration, description, free indirect speech, suspense, metaphor, and syntax”.[10] Such an analysis would, it is implied, be likely to exclude social and historical questions. By contrast, Levine’s new formalism would rather trace the often-agonistic parity between those forms seemingly enclosed within the bounds of the literary text, and the forms and structures into which social life sediments. Levine draws our attention to the following passage in Jane Eyre, the action taking place after the ringing of a school bell at Lowood School. The girls “all formed in file, two and two, and in that order descended the stairs”. Responding to a verbal command, the children arrange themselves into “four semicircles, before four chairs, placed at the four tables; all held books in their hands”.[11] Critics, Levine writes, are used to “reading Lowood’s disciplinary order as part of the novel’s content and context…But what are Lowood’s shapes and arrangements – its semicircles, timed durations, and ladders of achievement – if not themselves kinds of form?”.[12]

This is only an initial example of the methodology employed across the book as a whole, meant perhaps only to set the scene, and Levine meets the first obvious objection rather well. “One might object’, she writes, “that it is a category mistake to use the aesthetic term form to describe the daily routines of a nineteenth century school.”[13] And yet as she rightly points out, ‘form’ as a term has hardly been restricted to aesthetics. Rather, in its very generality, ‘form’ has traveled through politics, through philosophy, through innumerable other domains, and it may nominate a particular object or describe a general property of a class of things. But does this historical usage justify treating with the same analytical brush Brontë’s use of metaphor, say, and her description of the spatial outlines of a social institution? Levine argues her case forcefully, noting that: “it is the work of form to make order. And this means that forms are the stuff of politics”.[14] Thus, Levine’s new formalism, far from shutting out questions of social and political import, will rather widen their pertinence, to include the rhyming couplet as much as the disciplinary enclosure of space or the distribution of self-regulating bodies. As a consequence, “[t]he traditionally troubling gap between the form of the literary text and its content and context dissolves. Formalist analysis turns out to be as valuable to understanding sociopolitical institutions as it is to reading literature. Forms are at work everywhere”.[15]

But hasn’t a crucial question been elided here? Even as Levine celebrates the ‘dissolving’ of the barrier between text and context, she presumably wouldn’t wish to claim that there is, as a result, absolutely no distinction to be made between the words that make up Brontë’s narrative, and the arrangements of space that are her referent. Presuming this much, we are still to learn how it is that these two very different things are to be explained according to the same, now highly capacious, perhaps too capacious, definition of ‘form’. Even more importantly, how do these different forms come to relate to one another at all? To use a now unfashionable parlance, what is the theory of reference that underpins Levine’s account? One thing is clear: for Levine, there is no unidirectional line of causality from context to text, as in the less reflective of historicist readings; indeed, there is an even more radical argument about causality here that I will come to shortly. We get something of a more positive answer with Levine’s borrowing of the term ‘affordance’ from design theory. Affordances, we’re told, “describe the potential uses or actions latent in materials and designs”. Thus: “[a] fork affords stabbing and scooping. A door-knob affords not only hardness and durability, but also turning, pushing, and pulling”[16], and so on. Forms, on such a reading, are not merely reflective of a prior cause, content, or context; rather, they are active agents in their own right. Even literary forms, in their very abstraction, have affordances, one infers. But one wants to ask again how, precisely, one specific class of forms – literary forms – gain purchase on those other forms that jostle for attention? Or, in Levine’s terms, what are the particular affordances that literature possesses, over and above the material and action-oriented uses to which other forms may be put to use – which is not to say that literature itself may not have its own, specific material and action-oriented consequences? I will return to this question in much of what follows, it being, I would wager, a problem rather often avoided in much recent literary theory.

The reader may have noticed the distinctly Latourian cast of Levine’s analytical language, and it is a surprise that Bruno Latour is mentioned only twice in the main body of the text. Latour’s ‘actor-network theory’ has made much for decades now of how human and non-human ‘actants’ enroll and resist one another in a great tangle of moves and counter-moves. What I will come to call Levine’s liberal-ecumenical vision of formal complexity shares some of the same limitations inherent to Latour’s anthropologically-inflected social theory. One encounters an especially Latourian inflection when Levine raises the question of causality:

The first major goal of this book is to show that forms are everywhere structuring and patterning experience, and that this carries serious implications for understanding political communities…In theory, political forms impose their order on our lives, putting us in our places. But in practice, we encounter so many forms that even in the most ordinary daily experience they add up to a complex environment composed of multiple and conflicting modes of organization – forms arranging and containing us, yes, but also competing and colliding and rerouting each other. I will make the case here that no form, however seemingly powerful, causes, dominates, or organizes all others.[17]

I wonder whether the appeal to the theory/practice dichotomy here is more telling than it might initially appear. Latour has been especially critical of the legacy of theoretical critique, of what we can refer to by shorthand as ‘critical theory’.[18] In Latour’s case, one surmises that this is, in large part, a distaste for Marxism especially, and while Althusser, Gramsci, Jameson, Roberto Schwarz and numerous others have done much to complicate the model of causality inherited in the tradition, it would still be fair to say that doing without a theory of causality at all, as I think is implied by the final sentence above, would be unthinkable for every but the most ‘post’ of ‘post-Marxists’. And for all the usefulness of the language of overdetermination and structural causality, it is hard to imagine a major Marxist work of criticism in the last 50 years or so, from Raymond Williams onwards, that could have gained much analytical purchase without this most central plank of truly critical writing. And one also wishes to ask who, including Marx himself, ever argued for a theory of literature or society that privileged one form apparently able to ‘cause, dominate, or organize all others’?

Levine’s skepticism goes further. As well as lamenting the reductions of causal analysis, she also draws on Roberto Mangabeira Unger to lament any emphasis on deep structures or hidden ideological causes, ranging herself implicitly in solidarity with the trend for ‘surface reading’ first announced by Stephen Best and Sharon Marcus.[19] Such a structural focus, Levine laments, “limits our attention and our targets to a small number of the most intractable factors, factors so difficult to unsettle that most people abandon the attempt altogether. What if we were to see social life instead as composed of ‘loosely and unevenly collected’ arrangements…?”.[20] Just as Marcus and Best rather crudely mischaracterize the ‘depth reading’ that they wish to contest, so Levine risks recourse to the straw man here. After all, the best of structuralist reading, in both its formalist and Marxist manifestations, understands structure not in monolithic terms, but rather as, precisely, multiply caused and complex. But where structuralism would still, nonetheless, wish to maintain a nuanced but firm rubric of causality, Levine’s ecumenicism – or, to be less generous, eclecticism – threatens, I think, to replace analysis with sophisticated description. The condition of a globalized capitalism is much as she intimates: hyper-sophisticated, hyper-mobile, making little of previously intractable barriers to temporal and spatial transport. But these are also, yes, surface features that frequently obscure the division of labor that conditions their existence. And what is to be gained by recoding our oppositional languages of analysis in the terms of those phenomena we wish to challenge? Might we further lose what little critical edge literary theory may still, potentially, possess by glossing it in the same, quasi-Deleuzian terms, as the site of what Levine calls “collision” – “the strange encounter between two or more forms that sometimes reroutes intention and ideology”?[21]

Thus far, I have concentrated only on the opening, general theoretical vision offered in the book. My task now is to test my excitement at Levine’s bold vision and my skepticism as to signal aspects of that vision by reference to her case studies, organized around the central ‘forms’ of wholeness, rhythm, hierarchy and network. Along the way, I will sketch an alternative emphasis, one that may adopt the best of the Marxist tradition while not losing sight of literature’s capacity to absorb and reroute those variables that impinge on it from without.

Wholes

It is fair to say that wholes and totalities have been held in some suspicion in recent theory. One of the strengths of deconstruction, but also surely one of its weaknesses, was its almost-exclusive attention to how seeming unities are, in fact, unstable masks for difference. Levine’s chapter on wholes, the first of her book, is one of its strongest. She acknowledges the usefulness of deconstructing wholes when such unities exclude more than they include, but also observes how “we cannot do without bounded wholes: their power to hold things together is what makes some of the most valuable kinds of political action possible”.[22] I wonder, though, whether this insightful observation, one that would presumably make a virtue of types of more or less hierarchical political organization that have otherwise been unfashionable on the Left for some time, is in tension with Levine’s theoretical commitment to the decentered tessellation of mutually enrolling formal actors. Presumably, Levine would wish to acknowledge and celebrate both possibilities, although it is at this point, at this moment of an all-emcompassing inclusiveness, that the harder, properly political job of decision – of choosing one form or tactic over another – becomes all the more pressing.

Of particular use in this first chapter, at any rate, is Levine’s demonstration of how a consummate anti-formalism, Mary Poovey’s in this case, must in fact rely upon a tacit commitment to form to ever get off the ground. Poovey has made much of the claim that even post-structuralism had to rely upon forms of totalization and boundedness that it rhetorically set itself against. It is, then, something of a scholarly coup to prove, as Levine decisively does here, that the rather pious historicism that Poovey sometimes risks purveying is as formalist as any other analytical procedure must be. The argument is obvious, for sure, but striking for all that: “It is important to note that Poovey’s book [Making a Social Body] is itself organized by the single containing form that she criticizes: the concept of the social body” and “her central terms – cultural formation, body, domain, economy – are…containers, unifying concepts that can gather together disparate objects and traverse historical periods and contexts”.[23] In some of the more severe historicist criticisms of theory, one sometimes gets the sense that conceptuality itself may be dissolved in the acid bath of the tantalizing historical anecdote or glinting detail; it is useful to be reminded that these accouterments would not be legible without the affordances of form, or, in a more Kantian register that Levine flirts with but never quite commits to, without language’s structural conditions of possibility.

The positive examples offered by Levine of the affordances of bounded wholes are equally interesting. Taking as her source Elizabeth Gaskell’s Victorian state of the nation novel North and South, Levine contests those critics who have read in the novel’s ending a quintessential example of the suturing function of ideology. Endings are here read as that which cements the novel form as a whole; Levine quotes Terry Eagleton, for instance, who famously located in the neat endings of canonical nineteenth century realism the imposition of artificial bourgeois unity.[24] But as Levine notes, the ‘ending’ or ‘closure’ of the novel’s form is also a beginning and an opening: “what the novel imagines in its conclusion is really not an enclosure at all, but a beginning – the launching of a series of social and political relationships…that have significance as a model for the nation precisely because they will endure beyond the narrative’s end”.[25] There are, admittedly, a whole host of philosophical problems around the status of fiction that are glossed over here; what does it truly mean, after all, to say that fictional relationships carry on after the conclusion of a novel? It may well be that Levine means to evoke those real social and political relationships that North and South fictionalizes, but this would require a finer theory of fictional reference than is provided here.

But Levine’s intention is not just to find openness where others have found closure, or to expose open-ended forms where others see only oppressive boundedness. In line with her ecumenicism, openings and closures are allowed to coexist on the page. Of more moment is Levine’s interest in instances where different forms collide. In line with a number of recent critics, North and Soutb is read here as a novel impacted by transatlantic political pressures, etched into the very geographical distribution of the novel’s action. The industrial traffic between the North and the South of England relied in part on the flow of cotton from the antebellum southern US; while Southern England generally supported abolition, as did Gaskell, the North supported the status quo, a geographical inversion that prevents Gaskell, so we’re told, from resolving the different forms that make up her novel. But why?:

[t]here are at least three forms at work…: the form of the novel’s ending, which offers a set of contracts and agreements that are intended to organize relationships into the future, and the forms of two split nations, each seeking to create unity across differences…there is no way for Gaskell to resolve the bounded shapes of North and South into a satisfying conclusion…In the end, she opts for the unity of her own nation [via the marriage between a Northerner and Southerner at the novel’s conclusion], but she is distressed to find that she has necessarily sacrificed both her own abolitionist commitments and her desire for another nation’s unity along the way.[26]

It’s an intriguing argument, albeit one made almost entirely with a fairly conventionally imagined notion of historical and social context. Levine’s broader intention to expand our definition of form beyond narrative shape or poetical meter is well taken, but one wishes that she had been more explicit about the specificity of the relationships between the forms she is so keen to trace, whether or not some minimal notion of causality might have helped in the process. Presuming that the geographical arrangement of the United Kingdom is not literally reproduced on the pages of Gaskell’s novel, what happens to such a geography’s political valences when they are filtered, mediated, formalized, through the various micro-displacements of literary language? To answer such a question would require a closer reading than Levine often seems willing to pursue, at least here, perhaps in the fear that doing so would reproduce the ahistoricism of formalisms past. But I wonder whether a sufficiently close reading might, to the contrary, find at moments of apparent formal insularity, of the most solipsistic points of a literary structure, the place at which apparently ‘external’ social or historical variables are transformed, are rendered literary. This, at least, was the intimation of Paul de Man, whose late essays came close to identifying the dihesences of literary form as an especially salutary source from which to trace what the critic explicitly called the ‘materialist’ interruptions of history. Suffice to say, the full consequences of this late turn toward history as a formal instance were muted by de Man’s premature death.[27]

Rhythm

Something of this possibility is, nonetheless, explored by Levine in one of the more impressive close readings of the book, a treatment of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poetry that concludes the chapter on ‘rhythm’. The republican Barrett Browning’s ‘The Young Queen’ (1837) makes use of the occasion of a royal succession to explore various kinds of temporal passing, or what Levine calls “the organization of temporal experience” in this “national event”.[28] The poem explores how one moment of passing away – in this case a literal one, the king’s death – must be rudely interrupted by another transfer, the passing of power to a new monarch. Multiple rhythms come together in these stanzas: “the moment of death, the ceremonial time of the funeral, the transition from childhood to adulthood, and the abrupt transfer of state power”.[29] But Levine’s attention here is not simply on the social times and spaces evoked by the poem – a focus that threatens to seem one of content, not of form – but it also falls on the formal metrical means by which those phenomena are transformed and refigured on the page. There is no clear cut means by which the meter of the poem supports or undermines its content; as Levine notes, “Barrett Browning opts neither for a highly regular, standardized rhythm, as might celebrate the peaceful transmission of power, nor a jerky and abrupt one, such as might point to the shock of death as an integral part of the institution of the monarchy”.[30]

Instead, the poet chooses an imperfect but nonetheless regular rhythm, one both redolent of traditional prosody and productively distant from it. This is not, Levine insists, a mere symptom of Barrett Browning’s liberal gradualism, her choice of political reform over revolution, but is rather an attempt to give each distinct social and political tempo evoked by the poem its own space and emphasis, while insisting upon their inextricable intercalation. “We cannot have the peaceful transmission of power without death”, Levine writes; “we cannot bury the measured and respectful ceremony while also waiting for the young queen to feel ready for her new responsibility…The social situation…demands the coexistence of multiple tempos – the simultaneous workings of diverse speeds.”[31] Predictably, perhaps, we’re back to the teeming agon of forms that is the book’s signal motif, almost its theoretical tic. But Levine makes another, more original claim, namely that the awkwardness of the meter renders it “notably incommensurable with the forms of the social world”. “This”, Levine writes, “is a poetry that proclaims the independence of prosody, its refusal to be read as merely epiphenomenal”.[32] But the surprising implication of this is, for Levine, a democracy of forms, each unable to fully dominate the other: “like other rhythms, poetry can impose order on time only in a social context constantly organized and reorganized by other tempos”.[33] Somehow incommensurability shades imperceptibly here into a network of easily commensurable but distinct entities in polite conflict with one another. After all, if this poetic form was truly incommensurable, how could it be ‘reorganized’ by other tempos? Isn’t part of what makes something incommensurable its resistance to influence from those things with which it cannot be made congruent?

But why should this universalization of agonistic formal interaction result from one form’s bid to assert its contingent independence, its relative autonomy, to coin a phrase? Doesn’t poetic form instead have an unfair advantage over the other forms in question, given that it is, after all, a poem that we’re reading, and not a report or work of journalism? And might this not be a good thing, given that, as readers who have, at least at this putative moment in time, chosen to read a poem rather than, say, a work of political theory, we may wish for something particular, even special, from poetry’s specific capacities? This may be as true for relatively conventional verse such as Barrett Browning’s as it is for poems whose formal properties are more clearly experimental or out of the ordinary. Consider the final, rather overwrought stanza of Barrett Browning’s ‘Cry of the Children’:

“Pheu pheu, ti prosderkesthe m ommasin, tekna;” [[Alas, alas, why do you gaze at me with your eyes, my children.]]—Medea.

They look up, with their pale and sunken faces,

And their look is dread to see,

For they think you see their angels in their places,

With eyes meant for Deity ;—

“How long,” they say, “how long, O cruel nation,

Will you stand, to move the world, on a child’s heart, —

Stifle down with a mailed heel its palpitation,

And tread onward to your throne amid the mart ?

Our blood splashes upward, O our tyrants,

And your purple shews your path ;

But the child’s sob curseth deeper in the silence

Than the strong man in his wrath![34]

If, instead of assuming that the poem’s forms mix seamlessly if agonistically with its social referents, we remain faithful instead to Levine’s initial thesis of incommensurability, where might we locate its effects in this concluding stanza? The poem is, clearly enough, a sentimental, state of the nation address, indicting widespread child labor. It is not, on the whole, a poem that has found favor with modern critics, who have, needless to say, preferred irony, indirection, indecision. Dorothy Mermin has called the poem’s meter “awkward” and has lamented the poem’s “appeal to our feelings” as “inartistically explicit”.[35] More recently, Victorianists, Levine included, have sought to redirect attention to the powerful ethical claims that make of the poem a forceful social actor. The poem’s detractors, in other words, make reference to the poem’s form, while its defenders focus on its content. But what if we were to combine the insights of both camps, while stripping Mermin’s commentary of its negative tone? For the meter is, indeed, awkward; the poem resists a lilting or mellifluous rhythm, one that might heighten the poem’s sentimentality while perhaps smoothing off its rather overbearing religiosity, and neither does it adopt a martial thrust, one that may underscore its attempt to rouse action. As Levine rightly notes, the meter is neither here nor there, neither regular nor exactly inconsistent. More technically, the poem is arranged in two lines of iambic pentameter, followed by a line of seven iambic feet, a combination not unlike the ‘poulter’s measure’ identified by the 16th Century poet George Gascoigne, where lines of 12 and 14 syllables alternate.[36]

The effect of all this, however, is, I think, rather different than that identified by Levine. Where for her, the slight departure from expected form supports the poem’s ecumenical arranging of ‘multiple tempos’ (although I’m not sure one ever quite receives a precise argument as to how this form of mutual support occurs), I would instead argue that the poem’s rhythm grants a distinct sense of artificiality to proceedings. By pointing to itself, even if only subtly, the slightly ungainly tempo of the verse underscores a constructed domain, a domain in-process, the literary itself, which is distinct from, perhaps even incommensurable with, the social forms that the poem pictures and that its defenders, Levine included, tend to dwell on. This doesn’t undermine the punch of its social message; in a strange way, by drawing a trained eye’s attention to the distinction between two kinds of form, Barrett Browning sharpens our sense of both. The very distance between poetic artificiality and the social referent is, I would suggest, what makes us aware of each. This is another way of saying that poetic form isn’t necessarily intended to mean anything, or to support a poem’s themes, whether we think of those themes as its ‘content’ or just as other forms to be traced.[37] To suggest, to the contrary, that the poem merely holds tessellating forms together is, I think, to risk blunting this capacity of the constructedness of poetic form to heighten our apprehension of the difference, even incommensurability, between forms, between the limp of a marginally askew meter, say, and the squalid social spaces of Victorian Britain.

There is another way to read this inbetweenness of the poem’s form – neither conventional nor quite unconventional – that would locate, in the poem’s avoidance of any ostentatious break with convention, the source of its formal power. Just 50 or so years after the publication of Barrett Browning’s poem, Stephane Mallarmé, in his aforementioned ‘Crisis of Verse’ essay, recommended that poets maintain significant aspects of prior verse forms, only gradually tweaking their tempos in order to accentuate the awkwardness of fit that results. As we’ve already noted, this is for Mallarmé a more radical gesture than an absolute embrace of vers libre, which, by leaving behind any conventional ‘other’ from which to distance itself from, paradoxically deflates its own sense of distinctiveness. By holding the two in nervous tension, Mallarmé implies, one makes of poetry its own distinctive praxis, albeit one not thereby entirely cut off from its referential potential. It is interesting to entertain the thought that, previously and in an apparently much less experimental milieu in England, a Victorian poet might have, consciously or unconsciously, inched along the path to a similar strategy, and quite aside from Manley Hopkins’ own late-Victorian commitment to that other famous eccentric bridge between regular and irregular verse, sprung rhythm.

Network

Levine’s tracing of these different forms culminates in a concluding chapter on The Wire, David Simon’s recent and much lauded television series, chronicling overlapping formal and informal economies in Baltimore. The series has been much talked about in academic circles, with various conferences, symposia and articles focusing on its intricate plotting of the consequences of neoliberal urban restructuring, or on its complex relationship to canonical forms of narrative realism.[38] If, as is Levine’s ambition, cultural studies must “take account of what happens when a great many social, political, natural, and aesthetic forms encounter one another”[39], the multilayered character of The Wire, with its aggregation of multiple, internally heterogeneous institutions, scores of characters, and numerous distinct social spaces, would seem an ideal object for such a project. The series emphasizes both the grip that multiple institutional structures have on modern urban experience, and the scandalously uneven distribution of resources that such (post)modern cityscapes afford. Even as the series gleefully adopts and celebrates genre conventions, not least those associated with the cop show, Levine also sees in the series something of an updating of the best of nineteenth century realism; “Not unlike Bleak House”, she writes, “The Wire expands the usual affordances of its medium by intertwining over 100 characters in multiple intricate sequences that overlap and reshape one another”.[40]

As in the other readings that populate the book, Levine attempts to chart the ways in which forms both enable and frustrate each other’s claims to autonomy. Its status as fiction, far from being a hindrance, in fact allows the construction of a social theory close to the original roots of theoria, to the ambition to extract from a spectacle generalizable knowledge of the world. With an eagle eye, Levine digs deep into the multiple localities or ‘wholes’ that make up the space of The Wire; she is attentive, for instance, to events in the series’ third season, where a police chief creates ‘Hamsterdam’, an unofficial zone of drug legalization that shifts drug sales from their usual spots on street corners into a strictly bounded series of locales. But this apparently isolated and largely hidden social experiment soon rebounds on other enclosed wholes depicted in the series. As Levine writes, “Mayor Clarence Royce is momentarily impressed by the success of the zones, and his delay in shutting them down helps to bring about his defeat in the election, catapulting Tommy Carcetti into leadership of the city and eventually the state”.[41] And thus, multiple intertwined structures – a spatial enclosure licensed illegally by a policeman operating outside his jurisdiction, the official police bureaucracy, the media, interlaced local and extra-local political hierarchies – collide, with effects as complex as the original interaction of the forms in question.

Here, a specified and local space – the free drug zone – fans outwards in influence, with the other forms it interacts with responding in turn. All of this one would concede, but in order to pass from sophisticated description to analysis, at least some recognition of underlying impetus, of causal push, is surely necessary. Levine makes passing reference to those scholars who have read The Wire, even in its commitment to local particularity, as an allegory of contemporary hyper-capitalist deracination, but she implies that such a reading would necessarily mute those multiple other forms, those shapes or rhythms not entirely reducible to the economy, that populate the series. But why? To invoke a category such as capitalism is certainly not to deny the ‘affordances’ of local forms, but it is to recognize the dialectical interaction of those forms with an absent totality that, partially but powerfully, structures them in perpetuity. To insist on such interaction as ‘dialectical’ is already to agree with Levine’s insistence that such particularities are capable of resisting, even displacing, their animating frames, but it also pushes us towards asking bigger questions, questions as big as the spaces that The Wire pictures. A theory of causation must, I think, underpin Levine’s account, whether rendered explicit or not, not least because the language of forms ‘colliding’ and ‘intermixing’ already presumes a set of conditions within which such events could occur. My hope is that the details of this account will become clearer in subsequent work.

It may well be that Levine’s analytical framework is too general to deal with the local causal interactions that she insists are too complex to ‘reduce’. By this I mean that, in approaching any local object of analysis, the language of entanglement and affordance tends, not always but often enough, to obscure the very differences that it sets out to celebrate; the particular threatens to be lost by virtue of a paradoxically static language of generalized difference, one that turns around a few linked adjectives and nouns: ‘complex’, ‘collision’, ‘entangled’, and so on. Consider the following passage, a remark on The Wire’s fourth season, the year that focused in particular on the school system: “Each child’s story emerges out of a complex collision of social forms that can never be limited to one or two dominant social principles – race, economics, the city, the family, politics, the law, or education – but takes shape amid the pressures of all these and their constantly colliding patterns”.[42] Of course, there is never any fixed trajectory to social phenomena, no absolute pattern set in advance that would make the mapping process a foregone conclusion. But in practice, social forms, indeed aesthetic forms, are limited in their trajectories; retrospectively, one is often able to identify dominant factors that caused a particular event or made one thing more likely than another. To insist otherwise is potentially to blunt theory, and disable political action.[43]

In the penultimate chapter on ‘Networks’, Levine seems to admit as much, as when she writes: “it is clarifying and practical to isolate a single network and pursue its impact, since when networks are thrown together they can seem messy or incoherent. But it is also misleading to treat them as separate”.[44] I would insist that isolating a single or even a small sample of networks and interpreting their causal interaction is not necessarily to risk ‘treating them as separate’. To the contrary, analytical self-selection, even a certain blindness, is foundational to any project of inquiry, and it seems a fair assumption that, with all the constraints of the social and material world, such limitations are inherent there too. For all that, such a disciplined gaze does not require ignorance of the fact that, beyond the borders of one’s analysis, there may well be further connections to be pursued, or latent links to be activated upon the irruption of another social event. And it doesn’t seem overly reductive to claim that the one thing that all the forms delineated in all their messiness in The Wire have in common is their being impacted, for the worst, by the effects of a feral capitalism, one whose contemporary surface complexity should not become an alibi for our losing sight of its increasing definition of, and disproportionately adverse impact upon, the contemporary human condition.

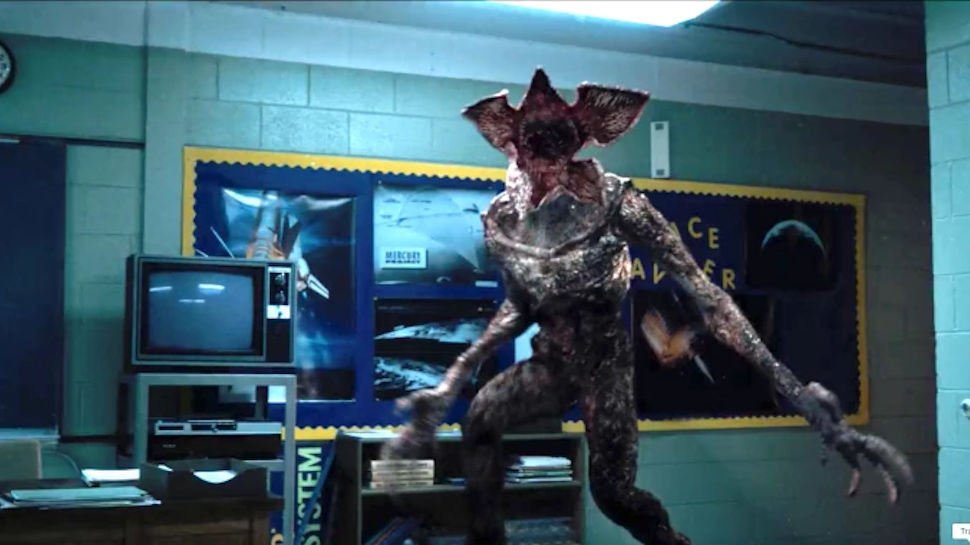

One final brief comment on The Wire before I conclude. In my take on Levine’s analysis of Barrett Browning’s poetry, I argued that the very separation of poetic form from its referents – in that case, the degraded social spaces of Victorian London – had the effect, far from undermining the poem’s active effect in the world, of instead drawing an ever greater attention to the latter; through a kind of negative mutual constitution, the very disengagement between the two is the key to the sharpness of each. Levine is fairly quick to pass over the generic status of The Wire[45], arguing that a more directly sociological attention to its treatment of political form better gets at its relevance as a cultural object. But might we not expect a similar process of formal disengagement in a television serial that, after all, and in contrast with those who have insisted upon its realism, makes quite the show of its generic borrowings? While I have no space to pursue this claim in any depth, I would suggest here only that the amplified, often absurd, nature of those generic appropriations – think of the exaggerated, cartoonish aspects to lead detective Jimmy McNulty’s self-destruction, a trope of the cop show if ever there was one – only makes the social ‘content’ that much more compelling; as the Russian Formalists who I began with may have put it, these two impulses – formal artifice and social realism – are mutually estranging in The Wire, but this separateness, so warded against in Levine’s analysis, is precisely what makes it such an accomplished televisual reflection on the deformations of capital. Somehow, even the show’s generic investments are warped by its subject matter, becoming outsized, even absurd, absorbing the excesses of the political phenomena in question even at points of apparent generic self-reference and pastiche. But those same generic investments are what inoculates the show against the ‘state of the nation’ piety that afflicts Barrett Browning’s ‘Cry of the Children’.

Conclusion

For all of my quibbles with the details of Levine’s new formalism, this impeccably well- written and always provocative book should initiate a serious and sustained debate in the Humanities. For too long, previously critical forms of historicism have threatened to repeat the errors of older historical methods, and one way of clawing back that criticality may be to reacquaint ourselves with the potential of formal analysis, in the process reinventing it anew. The temptation to be avoided, as I suggested at the outset, is a retreat into form, the foregrounding of reassuringly abstract figures or techniques at the expense of political salience and social relevance. But equally troublesome would be the assumption that abstraction and formality are inherently apolitical and ahistorical. One of this book’s many virtues is its activist insistence on the political effectivity of forms, of how we are conditioned, limited and enabled by multiple formal shapes and rhythms. But there is further work to be done, not least on tracing with a keen theoretical eye the ways and means by which different forms interact, in inherently uneven spaces of political, historical and aesthetic action and inaction. I remain unconvinced that assuming this interaction a priori is quite enough, and it may as a consequence be necessary to resurrect that most unfashionable of things, a theory of reference. Caroline Levine has made some crucial first steps in that direction here, and one hopes that this volume’s ambition won’t remain an exception to the regrettable over-specialization of contemporary Humanities scholarship.

Notes

[1] L. Trotsky, Literature and Revolution, ed. William Keach, (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2005), 153. Quoted in V. Erlich, Russian Formalism: History-Doctrine, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981), 104.

[2] Viktor Shklovsky quoted in V. Erlich, Russian Formalism: History-Doctrine, 109.

[3] M. Levinson, ‘What is New Formalism?’ in PMLA, 122.2, March 2007, 558-569.

[4] R. Wellek and A. Warren, Theory of Literature, (Orlando: Harcourt, 1956), 28.

[5] A special edition of Representations entitled ‘Surface Reading’, edited by Stephen Best and Sharon Marcus, pursued this line of argument. See Representations, 108.1, Fall 2009.

[6] See, in particular, L. Althusser, ‘The “Piccolo Teatro”: Bertolazzi and Brecht’ in For Marx, trans. Ben Brewster, (London: Verso, 2005), 129-153 and L. Althusser, ‘A Letter on Art in Reply to André Daspre’ in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, trans. Ben Brewster, (London: New Left Books, 1971), 221-229.

[7] See S. Felman, ‘Education and Crisis, or the Vicissitudes of Teaching’ in S. Felman and D. Laub, Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History, (London: Routledge, 1992), 1-57.

[8] S. Mallarmé, ‘Crisis of Verse’ in V. Leitch (ed.), Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, (New York: Norton, 2001), 841-851.

[9] I pursue the implications of these ideas in my Speculative Formalism: Literature, Theory, and the Critical Present, (Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017), and in a forthcoming book with the title Romantic Abstractions: Materiality, Figurality, Historical Time.

[10] C. Levine, Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 1.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid., 2.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid., 6.

[17] Ibid., 16.

[18] B. Latour, ‘Why Has Critique Run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern’, Critical Inquiry 30, Winter 2004, 225-248.

[19] S. Best and S. Marcus, ‘Surface Reading: An Introduction’, Representations, 108.1, Fall 2009, 1-21. It is noteworthy that Best and Marcus attribute a quote in this article to Freud, when it is in fact to be found in the work of Carlo Ginzburg. It would be unkind to suggest that such a lapse might be an immediate consequence of rejecting critical practices of reading, but the danger at least should be registered.

[20] C. Levine, Forms, 17.

[21] Ibid., 18.

[22] Ibid., 27.

[23] Ibid., 33-34.

[24] T. Eagleton, Myths of Power: A Marxist Study of the Brontës, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005; reprint), 32.

[25] C. Levine, Forms, 41.

[26] Ibid., 42.

[27] See, in particular, the essays collected in P. de Man, Aesthetic Ideology, ed. Andrzej Warminski, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996). For work that extends these insights in productive directions, see A. Warminski, Material Inscriptions: Rhetorical Reading in Theory and Practice, (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013).

[28] C. Levine, Forms, 75.

[29] Ibid., 77.

[30] Ibid., 78.

[31] Ibid., 79.

[32] Ibid., 79.

[33] Ibid., 80.

[34] The poem was originally published in the August 1843 edition of Blackwood’s Edinburgh magazine. The full poem is available to read at the Poetry Foundation website: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/172981.

[35] D. Mermin, Elizabeth Barrett Browning: The Origins of a New Poetry, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1989), 96. Quoted in P. Henry, ‘The Sentimental Artistry of Barrett Browning’s “The Cry of the Children”’, Victorian Poetry, 49.4, Winter 2011, 535.

[36] C. Levine, Forms, 78.

[37] Jonathan Culler has recently reaffirmed how “rhythm, repetition, sound patterning [are] independent elements that need not be subordinated to meaning and whose significance may even lie in a resistance to semantic recuperation”. See J. Culler, Theory of the Lyric, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2015), 8.

[38] See in particular the special edition of Criticism devoted to The Wire. Criticism, 52.3-4, Summer/Fall 2010.

[39] C. Levine, Forms, 132.

[40] Ibid., 134.

[41] Ibid., 137.

[42] Ibid., 133.

[43] This is partly the argument of Carolyn Lesjak’s ‘Reading Dialectically’, a crucial article that takes up the argument of Levine’s original article on form ‘Strategic Formalism’; the latter is cited in note 5. A more sustained attention to Lesjak’s argument in this subsequent book would, I think, have been helpful, although one imagines that the appearance of Lesjak’s argument only two years before the publication of Levine’s book set practical limits to Levine’s engagement here. Nonetheless, Lesjak does receive passing mention. See C. Lesjak, ‘Reading Dialectically’, Criticism, 55.2, 2013, Article 3 and C. Levine, Forms, 18.

[44] C. Levine, Forms, 114.

[45] The most accomplished genre analysis to date, one referenced briefly if largely negatively by Levine, is F. Jameson, ‘Realism and Utopia in The Wire’, Criticism, 52.4, 2010, 359-372.