Rym Quartsi

العربية | Français

The aim of this essay is to explore how women experienced violence in Algeria during the black decade (1992-1999)––a time of political and social turmoil––through the lens of the films that have emerged in the period since. The black decade designates the period of violence that took place in Algeria after the dissolution of parliament and cancellation of elections in 1991. The conflict between armed Islamist groups and the Algerian army led to the assassination of civilians, intellectuals, and the displacement and exile of the population. More specifically, this essay is an attempt to explore how these Algerian films depict violence in relation to gender and how they utilise language as a symbol of ideology.

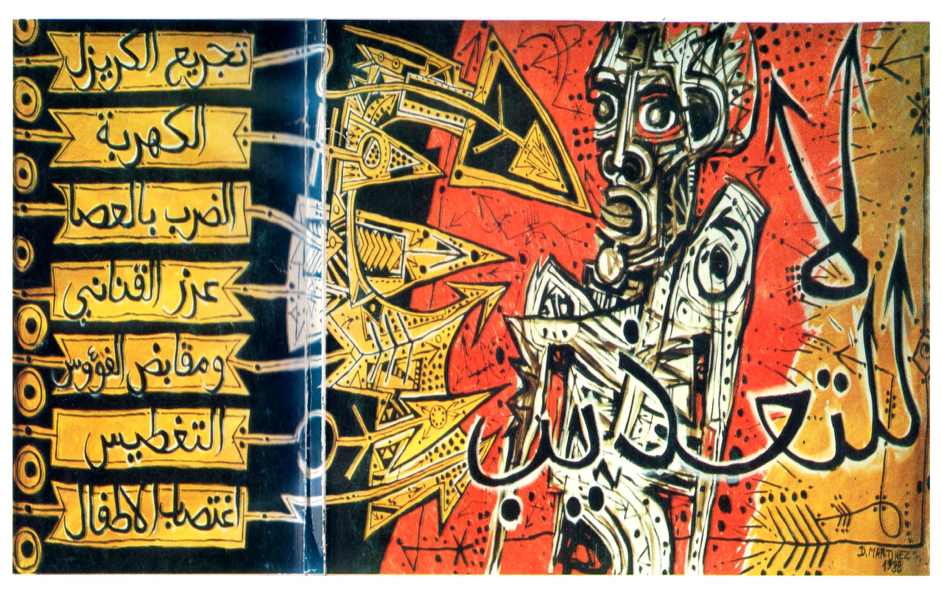

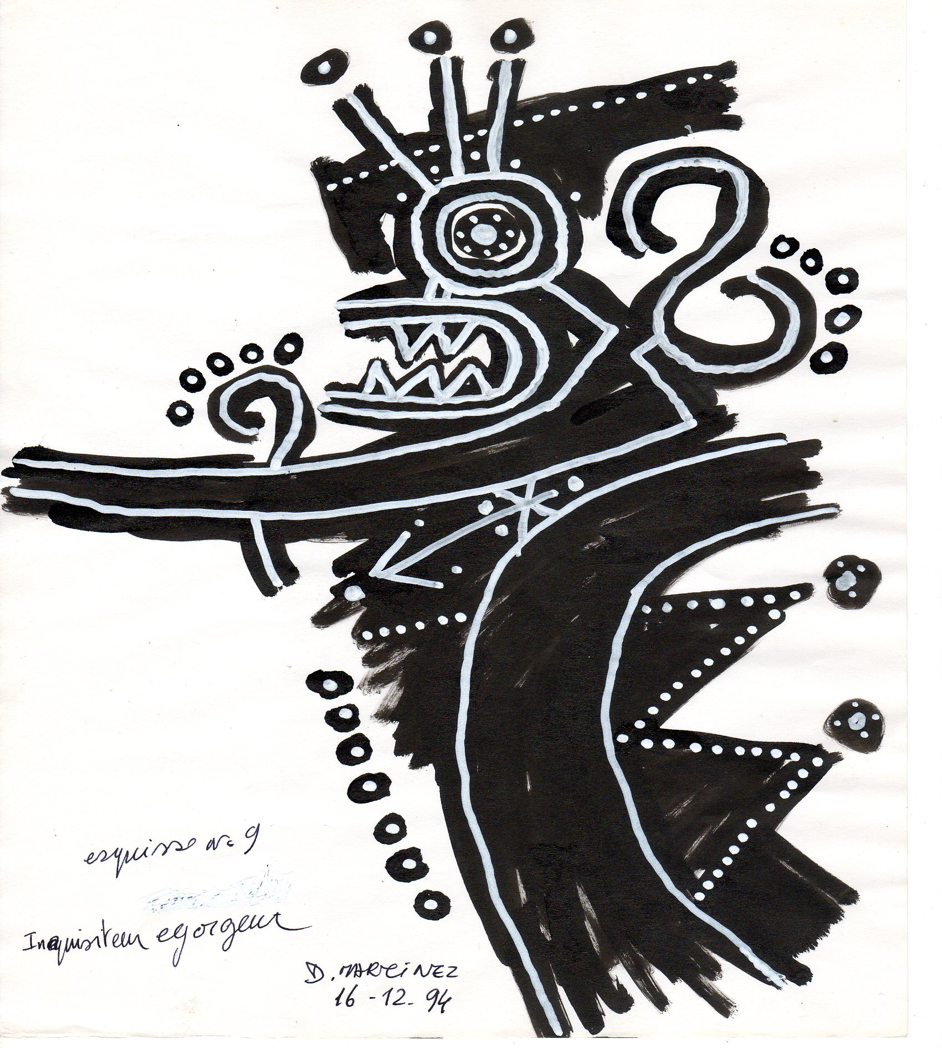

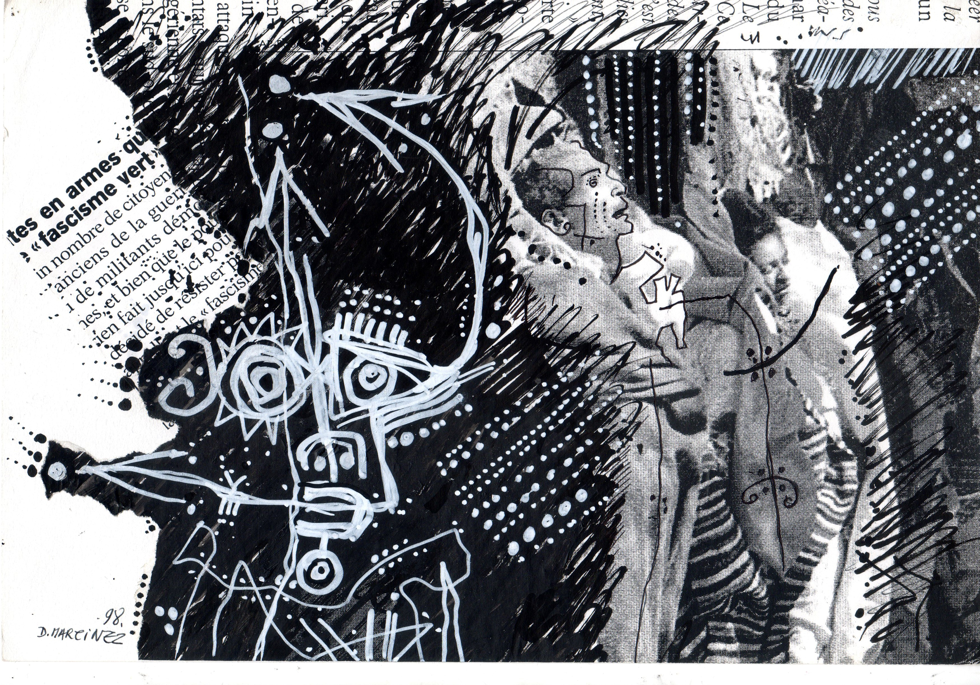

Although films are shaped by a director’s subjectivity and by constraints of materials and time, they are also determined by the culture that produces them. Films often form part of the social narrative of a given period in history and offer a lens through which to analyse the impact of significant events. The dismantlement of state structures that financed filmmaking, coupled with the unstable situation––violence in Algeria, death threats towards filmmakers and actors–– resulted in a dearth of film production during the 1990s. So few images of the conflict were presented in the Algerian media, that the historian Benjamin Stora described it as a ‘war without images’.[1] However, the resurgence of Algerian cinema after the black decade has coincided with the emergence of female filmmakers and films that pay more attention to the situation of women, contemporary issues and post-war trauma.

From the films produced after the black decade, I have selected three that range in both period and cultural setting: Le Harem de Madame Osmane (2000, Dir. Nadir Moknèche), Rachida (2002, Dir. Yamina Bachir Chouikh) and Barakat! (2006, Dir. Djamila Sahraoui). Co-produced by French production companies, Rachida and Barakat! received Algerian state funding, and all feature women as protagonists. Each film is written and spoken in a different language: French, colloquial Arabic (darija) and a mixture of darija and French. My questions are: what is the role of language in each film? Does the use of language shape the way the film engages with gender, violence, and power relations? What does language bring to the characterization of the protagonists in each of these films?

Importantly, these films not only deal with the 1990s but in the cases of Le Harem de Madame Osmane and Barakat!, they also draw on the nation’s colonial past through the figures of the mujahidates––women who took part in the Algerian liberation movement against French colonial power (1954-1962).[2] I shall question how these events are remembered and expressed and the role language plays in doing so. Scholar Abdelkader Cheref observes that women’s movements were the only ones that could challenge both Islamists and the governing power during the black decade.[3] I will explore how they are seen to do this as both writers and protagonists in the films I have chosen and, in doing so, how they use language to respond to their situations. Before I am able to do so, however, it is necessary briefly to outline the on-going debates around language in Algeria.

Language became a means of constructing national identity in post-independence Algeria. The politics of nation-building introduced after independence (1962) drew on the pre-colonial history of Algeria as an Arab and Muslim country: Modern Standard Arabic (a modern variant of Classical Arabic) became the official language, and Islam the state’s religion. The aim of promoting Arabic and Islam was twofold: to inscribe Algeria within the pan-Arabic nation––a political alliance of Arab nations––and demonstrate that Algerians had regained power over the French colonial rule when the Arabic language was marginalized––although there were moments in history where French schools taught Arabic (as a foreign language).[4] The politics of enforcing Modern Standard Arabic in public administration, schools and the media was known as Arabisation and was intensified over the decades through official texts. Arabisation also became an act of political expedience. For sociolinguist Mohamed Benrabah, Arabisation was furthered by various Algerian governments who sought alliances from pro-Arabisation hardliners to counter the politically influential Francophone elite.[5]

Establishing a unified language, as a core preoccupation of nationalism, also went beyond expelling traces of colonialism. Sociolinguist Catherine Miller argues that Algerian governments, post-independence, set more importance on annihilating local languages than foreign, colonial languages.[6] Non-Arabic languages were not considered part of the post-independent national identity.Even film directors had to conform to Arabisation and post-independence films, in the 1970s, used Modern Standard Arabic. Cultural artists, particularly Algerian novelists––such as Kateb Yacine, Assia Djebar, Rachid Boudjedra––made use of the diversity of languages to challenge the monolithic state authority, monolinguism, and the myths of nation-building. Similarly, Algerian filmmakers used language to investigate national identity and cinema, therefore asserting that nationhood is not linked to one language. In view of the ties between language and national identity, the survey of the three films will expose how language was used in films to resist violence during the black decade.

I. Rachida: Darija and National Identity

Rachida is the first feature film of Bachir-Chouikh who wrote and edited the film. Rachida received both national and international attention as it documented the era of the 1990s when bomb attacks had increased in frequency and the population lived in terror. Rachida circulated in international film festivals such as Cannes and won the Satyajit Ray award at the London Film Festival in 2002. The film was released in 2002, in Algeria and France, and attracted approximately 60,000 spectators in Algeria and 125,000 in France.[7] The number of 60, 000 is quite high, given that fewer than ten cinemas were open in 2002. Bachir-Chouikh stated that Algerian audiences were moved by the Rachida because it described the events they had lived through, something that had not happened since The Battle of Algiers (1966).

Bachir-Chouikh, born in 1954, attended the short-lived Algerian National School of Cinema and began her career as a script supervisor on two Algerian features: the big hit Omar Gatlato (1976, Dir. Merzak Allouache) and Wind of the South (1982, Dir. Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina).[8] It is worth noting that Omar Gatlato is one of the first films in darija; the film did not use Standard Arabic, thus going against the practice recommended by the State authorities. Rachida too is mainly in darija.

The story is inspired by a real-life event: the death in the Algiers Casbah of a teacher, Zakia Guessab, who was assassinated after she refused to place a bomb in her school.[9] The protagonist, Rachida, lives in a working class area of Algiers, with her divorced mother. One scene illustrates that she has no money to buy imported shoes; nonetheless we see that she does not lack nationalist moral fibre, as she aims to buy only Algerian shoes! On her way to the elementary school where she is a teacher, Rachida is threatened with a gun by a group of adolescents. The group asks her to place a bomb in the school. Rachida categorically refuses and is then shot, leaving her almost dead on the street. Amongst her attackers she recognized a former pupil. After she recovers, Rachida leaves Algiers and hides with her mother in a remote village where she eventually obtains a job at the neighbouring school. Once in the village, Rachida has to recover from the traumatic event she experienced: she often sits and rocks her head, listens to music, and has nightmares involving terrorist attacks. At the end of the film, the events repeat themselves; the terrorists raid a wedding, women are kidnapped, and people are killed.

Bachir-Couikh struggled to arrange financing, and spent five years gathering the necessary funds. The film was in the end largely funded by French-German television Arte, the Gan Insurance foundation and received some funding from the Algerian Ministry of Culture and Communication.[10] Bachir-Chouikh stressed that the same script was both presented to the Algerian committee for funding and to foreign funding bodies, which is to say, the script was neither censored nor modified to conform to particular funders’ expectations.

Bachir-Chouikh presented her film as an attempt to depict the violence ordinary women lived through. She meant to portray the life of the ‘simple and poor’, those who experienced terrorism but were not acknowledged in the media. She chose women to be the protagonist on the ground that: ‘women are the ones who give life, not death’.[11] Rachida was criticised by Algerian journalists such as Yacine Idjer, who considered the film to bear an over-simplified, stereotyped view of the Algerian situation at the time of the events.[12] Arabic-language Algerian newspaper Al Hiwar also criticized Chouikh’s film on the grounds that it depicted a distorted image of Algeria: the unemployment and marginalization of the youth, the failure of the state to protect the poor and vulnerable, and the situation of women who are seen as victims of the patriarchy.[13] Al Hiwar journalist argued that Chouikh is influenced by a ‘Western’ vision of the woman and disrespects Algerian values.[14] Nonetheless, the events presented within the village delineate the ways in which women and men endured violence during the black decade and gained international attention.

I shall now focus on two scenes that illustrate the use of language, and I shall offer further insights into how Rachida uses language to negotiate her way out of the violence she lived and the trauma she continues to endure. The first scene shows Rachida being asked by her pupils whether Algiers really is the ‘white city’ [in Arabic and in French Algiers is referred to by names which translate literally as Alger la Blanche]. She replies––presumably thinking of the association of whiteness with purity––that a country or a city will be white the day the people can live freely, fearlessly and with dignity.[15] Rachida addresses her pupils dynamically; the camera follows her as she moves and talks. The long shot embraces the classroom, and she is filmed from behind, focusing the audience on the rapt expression of the pupils as they listen to her. The camera movement enhances the feeling of intimate dialogue: she is sharing her thoughts and moves physically as her ideas are imparted. When the camera stops, Rachida resumes her activity as a teacher and begin asking for her pupil’s names in the usual manner of teacher taking a class register.

Scholar Abdulkafi Albirini argues that Standard Arabic is the language that brings ‘seriousness and importance to a topic’ whereas darija is the language that is ‘used for narration and giving concrete examples’.[16] However, Rachida reverses this statement and uses darija to convey ideological views. Prior to this scene, Rachida is introduced by a male schoolteacher. He clearly makes use of Modern Standard Arabic to warn the children that they will be punished if Rachida is given cause to complain about them. The association of Modern Standard Arabic with punishment and masculine authority contrasts with the way in which Rachida addresses her pupils and invites them to ask questions in the following scene. An association is made between darija and a gentler more sympathetic approach to education. The use of darija also brings to the scene a sense of verisimilitude since it is the everyday language used at home and outside school. The use of darija therefore creates proximity not only with the pupils but also with the Algerian viewer, and makes it clear that Rachida’s use of darija is an active choice.

The second scene contrasts Rachida with another female teacher. The teacher is filmed approaching Rachida and kneels to face her. A medium reverse-shot brings more intensity to the discussion they have. The teacher asks Rachida in darija whether she is married. A close up enhances the severe expression of the teacher as she asks: ‘why don’t you wear the hijab (the veil)?’. Rachida replies humorously that the doctor did not recommend it. The teacher is outraged that a doctor is given more authority than God, and cites a Koranic holy expression. Rachida replies with another Koranic verse thus demonstrating her mastery of Classical Arabic and Islamic precepts.

The use of darija in the scene initiates the dialogue with Rachida and gives a ‘natural’ turn to the discussion, though one nonetheless ideologically charged. However, when her use of darija fails to achieve the desired effect on Rachida, the colleague attempt to assert superiority by using Modern Standard Arabic instead, to quote religious verses at her. Rachida is conscious of the assertions implicit in her colleague’s use of Modern Standard Arabic and replies to her, in turn, using Modern Standard Arabic. The second scene is highly contentious and was criticised by the Arabic newspaper Al Hiwar for illustrating through Rachida’s rejection of the veil Bachir-Chouikh’s attachment to Western values.

The veiling of women was a political and religious stance taken by both the Islamic parties and, later, the armed Islamist parties: un-veiled women were associated with a lack of moral values and ‘real Muslim’ women had to veil in order to abide by Islamic laws and protect themselves from men’s gaze.[18] Rachida’s female colleague associates marriage and veiling with good morals and the preservation of female honour. She confirms that veiling corresponds to ‘modesty, obedience, sexual probity, conformity’ and that all these ‘qualities’ are ‘expressed publicly and overtly when [the veil is] worn’.[19] The female colleague interiorized and reproduced a discourse about the hijab. She also uses a rhetorical discourse to pressure Rachida and mixes darija with Modern Standard Arabic. The scene illustrates ideological antagonisms between women, who may nonetheless be fellow darija-speakers. There is no clear linguistic division, therefore, between representatives of opposing political ideologies. The discussion in this scene highlights the moral views of the female teacher and is informative of the village life. The depiction of village life brings under scrutiny gender relations, sexual tensions and patriarchal values: women need to preserve their virginity before marriage, almost all women are veiled, and a segregation of space between men and women is enforced.

Fatma, Rachida’s mother, who is also veiled, does not pressure Rachida into veiling. Fatma uses language and music to reassure her daughter and live through terror. While the actress who played Rachida (Ibtissem Djaoudi) was unknown to the Algerian public––she was still a student at the National Drama Centre––the actress who played her mother Fatma (Bahia Rachedi) was, to Algerian audiences, well known. Rachedi appeared in numerous popular television series and films, presented a famous cooking program, and was also part of the National Television Orchestra, as a singer, for thirty years. Journalist Yasmine Ben even named her ‘la gentille maman’ (the kind mother) because she was often cast in the role of loving, devoted mother.[20]

Rachedi is primarily a television star and conforms to James Bennett’s description of the television ‘personality’ as someone who cultivates a “televisual” image.[21] Bennett points to the ‘authenticity and ordinariness’ of the television star that produces ‘the confusion between the television personality-as-person and the televisual image’.[22] The character of Fatma is what one might call a classic Rachedi role and exemplifies many features of the actress’s own public persona. Fatma is pious to the point that she never misses prayer, and she questions how Islamist terrorists could really be Muslims. She uses humor, proverbs in darija and traditional Algerian popular wisdom to reassure and comfort her daughter.

Fatma often sings popular music that would be immediately recognizable to an Algerian audience. Her songs are derived from chaabi (Algerian traditional popular music) and hawzi music. Hawzi is soft music often characterized by lyrics that express suffering. It originates from northwest Algeria (Tlemcen) and is sung in its native dialect. Rachida often listens to Cheb Hasni, a popular rai singer who was assassinated during the black decade. Rai makes use of code switching between darija and French, and the songs often mix erotic content with stories of life’s dissatisfactions. Rai was first banned by the Algerian state media in the 1980s then condemned as amoral by the Islamists.[23]

Darija and music become the healing balm through which the mother’s love is communicated. Music allows Rachida and Fatma to escape the present and the situation they live in and opens moments of breathing space for them. Music also brings emotional resonance. The choice of diegetic and non-diegetic music that both refer to, or evoke, Algerian dialect(s), combined with the use of darija, root the film in the everyday landscape and customs of Algeria. Moreover, it aims at building upon cultural practices of Algerians who use darija, and resist the political and religious discourse of fundamentalism.

Rachida awakens into political consciousness as the film progresses. She angrily accuses the state of hogra: a politically charged common North African word, in darija, used to express resentment towards institutional power. Rachida also rejects the project of national reconciliation: she questions ‘how [one is] to forgive if those who tried to kill you did not ask for your forgiveness’. By the end of the film, Rachida is more the symbol or mouthpiece of an ‘idea’ than she is a fully formed human being. The way the character is filmed, through medium and long shots, with few close-ups, and few scenes filmed from her point of view, creates a distance between the viewer and Rachida. Indeed the scenes in which she appears most angry or traumatised are shot from another protagonist’s point of view. The last scene however is a close up on Rachida’s face: following a terrorist massacre of local people, she returns to school and writes ‘today’s lesson’ on the blackboard before looking defiantly into the camera. In this moment she completes her symbolic journey, finding a new home––and sense of purpose––in the school itself. The film does not challenge linguistic policies in Algeria but implies that the Algerian situation will change through women, education and schooling.

II. Barakat! Can we (women) speak to them (terrorists)?

Barakat! is Sahraoui’s first fiction drama. Sahraoui (born in 1950) studied filmmaking and editing at IDHEC (the French Film Institute) and produced six documentaries, some of which dealt with life in Algeria during and after the black decade: La Moitié du ciel d’Allah (1995), which is a feminist documentary about mujahidates and other women resisting terrorism; Algérie, la vie quand même (1998), which is concerned with youth unemployment in a Kabyle village and contains interviews with young people in the Berber language Amazigh; and Algérie, la vie toujours (2001), which explores life in a Kabyle village following the black decade.[25] Sahraoui co-wrote Barakat! with Cécile Vargaftig, a French script-writer and author. The film was mainly funded by French-German television Arte, and received little funding from the National Algerian Television. Sahraoui, like Bachir-Chouikh, intended the film to dispel image of Algerian women as ‘imprisoned, subservient women, as one sees so often in Algerian films’.[26]

The title Barakat! ––meaning ‘enough!’in darija–– is closely associated with two different protest movements. One of these (Sebaa Snine Barakat! Seven years are enough!) emerged soon after independence in 1962 and was a response to a period of murderous political conflict.[27] The other known simply as Barakat was the protest movement led by a female doctor that opposed the re-election of President Abdelaaziz Bouteflika in 2014. To add yet more resonance to the name, 20 Ans Barakat is also a women’s association in France and Algeria that calls for an ending to the Algerian family Code (1984).

Barakat! recounts the journey of Amel (actress Rachida Brakni) who is searching for her kidnapped husband. Amel is a doctor who lives on the outskirts of Algiers by the coast. Discussions at the hospital indicate that he had written a remarkable article on the Islamist terrorists. Amel embarks on her journey with the nurse Khadija (actress Fettouma Bouamari) after her neighbour, a mechanic, has indicated that her husband is to be found in the nearby maquis (bush terrain).[28] A former mujahida, Khadija takes with her a gun and a haïk––a traditional outfit that veils the body and recalls the disguises used by women and men during the Algerian war. Both Amel and Khadija set out walking into the maquis but are soon kidnapped by terrorists. Khadija recognizes one of the terrorists, with whom she converses in French and darija. He was a mujahid––male combatant during the Algeria war of liberation–– whose life she saved by nursing him after an attack by the French in which he was severely wounded. The mujahid became a pious man, but also part of the terrorist group. After the terrorists release Amel and Khadija, the women continue walking until they encounter an old man living in an isolated house who gives them a lift home on his horse-drawn carriage. The old man who lives on his own had his sons disappeared. Back at her house, Amel and Khadija suspect the neighbour and find Amel’s husband in his garage. At the end of the film Khadija and the old man are by the sea and enjoy a sense of freedom, both shouting ‘Barakat!’ after the old man has thrown Amel’s gun into the sea.

The film presents an encounter between two women who overcome violence and learn to know each other while venting their fear, anger and thoughts about the situation they face. It is also a cross-generational encounter between two actresses notorious for their political commitments: Rachida Brakni a young French star with Algerian origins and Fettouma Bouamari, an Algerian actress who moved to France during the terrorist era. Barakat! circulated in international festivals and won the best film award at Dubai Film Festival in 2007, and multiple awards such as best first feature, best music and best screenplay at the Pan African Film and Television Festival in Ougadougou (FESPACO) in 2007. The international awards did not coincide with the press reception in Algeria. Algerian Arabic-speaking and French speaking journalists generally agreed that Barakat! was a technically mediocre film and that the awards were given in virtue of its intellectual audacity rather than the artistic accomplishment of the work.[29] The debate in the Algerian newspapers was concerned with the image of the nation that the film presented. French and Arabic speaking newspapers vehemently attacked the film because it tarnishes the image of the mujahidin by linking them to terrorists. [30] Algeria’s national narrative relies on the events of the glorious war and the actions of the mujahidin in defeating the colonial power. It is interesting to notice that these press reviews ignored the role played by the mujahidates during the war. For journalist Fatiha Bourouina the film distorts the image of the Algerian nation by suggesting that the state was incapable of protecting the population.[31] The film also undermines the state’s image by asking the question ‘qui-tue-qui?’ (who kills who?). [32] This question recurred during the black decade in the French media because the Algerian army was suspected of taking part in terrorist acts.

Arabic-speaking Algerian newspapers did not discuss the use of French language in the film. Journalist Hind O, writing in a Francophone newspaper, argued that French funding imposed the use of French language otherwise how one can explain that a young thug speaks French.[33] In an interview, Sahraoui justified the use of French and darija since it reflects Algerian reality.[34] French-writing journalist Yacin Idjer, argued that having 80 percent of the dialogue in French damaged the authenticity of the film.[35] In his view, the narrative distorts reality by depicting two women walking on their own without fear of terrorists, Khadija smoking freely in the street, and Amel fearlessly threatening men with a gun in a coffee place.[36] Algerian journalists persistently criticized Khadija’s smoking on the street as if women’s smoking was an emancipatory act.[37] Although smoking may not be emancipatory, and Barakat! is a fiction, it is still striking the extent to which journalists reproduced in their writing a set of orthodox moral judgments about women smoking.

Amel and Khadija’s journey is visually enhanced by the film’s sound track and long shots that depict the beauty of nature: the sea, the maquis, and the mountainous roads. The contrast between the beauty of the landscape and the tragic events is heightened by the music. Throughout the film the oud (luth) of Alla is heard. Alla is an Algerian musician who was rediscovered in the 1970s when Algerian television broadcast his tunes. Alla invented hybrid music, the ‘foundou’ mixing Arabic and African rhythms.[38] Foundou expresses the suffering of the poor. In the film, Alla’s music is used to enhance moments of anxiety and doubt when Khadija and Amel are on their journey.

When Amel and Khadija are exploring the maquis they converse by means of code-switching, mixing darija and French. Code switching allows Amel and Khadija a certain freedom of speech: they resist the violence that is inflicted on them by terrorists instead speaking freely and crudely. Monica Heller considers code switching as one of the usual modes of speaking as it becomes adopted and practised by speakers, so code switching becomes a ‘normal way to talk’. [39] Furthermore, code switching, in Heller’s view, allows the speaker to access ‘multiple roles and relationships’.[40] I shall analyse how the protagonists use code switching to reverse power roles, and how code switching transcends generations, as we see when it becomes a common language between Amel the doctor who was raised in post-independence Algeria and Khadija who fought the French and uses darija and French language.

In one scene where Amel and Khadija are walking, code switching enables a change in their power relations. Amel expresses her anger towards Khadija in French, using the word ‘bricolage’ to suggest, critically, that the work done by Khadija’s generation during the war was just hastily thrown together. Khadija replies that without the ‘bricolage’, Amel’s generation would still be shining the shoes of the French (coloniser). However, Amel feels that, considering the escalation in terrorist activity, it might be better still to be a French colony. She describes the two situations as a choice between cholera and the plague.

One other scene allows Khadija to freely express, using darija and French, her views on gender relations impregnated with fundamentalist views. Khadija mentions to Amel that Amel’s neighbor never looks directly at her. He considers Amel as ‘aaryana’ (naked in darija) because she is not veiled, a dualistic view of the female body shared by both men and women in Algeria. As the scholar Anne-Emmanuelle Berger writes, a study conducted amongst female Algerian students showed that to most of them the female body only exists in two possible states: ‘naked’ or ‘veiled’.[41] She comments that, for these girls, the ‘Islamist garment being instituted as the criterion of resemblance and difference between women’.[42] Khadija’s disapproval of the neighbour’s views is to be understood in relation to her past as a mujahida. The neighbor posits himself as a moral authority but the name mujahida itself infused with religious meaning: it is an Arabic name derived from jihad associated with a war in the name of God. Khadija’s use of the haïk in a previous scene also confirms her awareness of the use of the veil as a disguise and not only as a guarantor of moral behaviors, stating, while dressing with the haïk: ‘ils veulent de la respectabilité, eh bien ils vont l’avoir’ (‘they [the terrorists] want respectability, then they will have it’). She therefore denounces, through the use of crude language, society’s hypocrisy towards unveiled women, although she is a mujahida.

The haïk is also symbolic of the anti-colonial struggle, being the very means by which, as Frantz Fanon argued, women resisted colonial power.[43] However, not all Algerian women accept the haïk as a ‘proper’ traditional veil. Berger remarks that girls wearing the hijab disregarded the haïk as a symbol of pre-colonial Algeria and of the Turkish presence.[44] The hijab was perceived as more compliant with the girls’ aspirations to be authentic Muslims because it was imported from the Middle East and had no connection to Algeria’s pre-colonial history.[45]

The film indicates also that terrorists were not only Islamists with strong religious ideology but encompassed mujahidin and ‘ordinary’ people, such as the mechanic. The description of the terrorists echoes also that of Rachida: they are described as young adolescents dressed in western outfits who do not seem aware of their goals, or the ideologies they support. Standard Arabic is absent from the vocabulary of the terrorists. In this way, the film implies that it would be a mistake to see the conflict of the black decade as one between Islamists Arabophones and secular Francophones. The use of code witching therefore becomes a common language between women and the terrorists, but is ideologically used in different ways.

The film suggests that code switching is the sole ‘language’ spoken in Algeria and understood by all protagonists, and as such the legitimate language of Algeria that is also able to encompass antagonistic ideologies. Code switching thus points more to different socio-political affiliations. The film, however, implies that the use of the French language was the reason why Amel’s husband was kidnapped. Amel cannot understand why the Islamists would kidnap her husband, since they do not read French.

The symbolism of the French language became a recurring theme of the Islamists’ discourse, even before violence erupted. Gilles Kepel states that Ali Benhadj, one of the FIS (Front Islamique du Salut) political leaders, wanted to remove the French presence ‘intellectually and ideologically’, and that the state itself was a ‘Westernized entity’.[46] Amel’s husband seems to be an opponent of the Islamists, as he is a Francophone journalist, although the content of his article is not disclosed. Amel’s husband conforms to the idea of the Francophone intellectual who fights Islamists’ views. The film accentuates the dichotomy between Arabophone––Arabic speaking–– and Francophone intellectuals.[47] Scholar Lahouari Addi suggests that Francophone intellectuals aim to attack the traditional structures of society while Arabophones are more critical of the state and less so of society. Arabophones aim at ‘extracting the cultural and political perversions introduced by the West’.[48] Addi notes that the involvement of Francophone elites in political life only resulted in a disconnection form the people.[49] Addi indicates that the assassination of Francophone intellectuals during the black decade did not lead to anger or despair amongst the population, and this indicates how little impact Francophone intellectuals had in public life.[50]

Sahraoui has inscribed Barakat! in the continuity of her previous documentary works where she explored the situation Algerian women lived. Barakat! is concerned with more than merely the actions of intellectuals; it questions the disconnection between men and women in society and plausibly suggests that women are the only ones who are resisting Islamists. However, not all women are capable of resisting Islamists, only determined, independent idealists such as Khadija and Amel, who value their freedom. The disconnection, however, between the old and new generation of women is visible in the way Khadija still defends her national ideals while Amel doubts the state’s actions and language does not act as a unifier in this instance.

III. Le Harem de Madame Osmane, gender, French language and power: a “natural” link?

The film is conceived as a huis clos of women and Moknèche makes distinctive use of space by confining the protagonists to only a few locations within a limited area.[52] The title of the film even alludes to the space in which Madame Osmane controls the women of the house, the harem.[53] The film, shot on location in Morocco making use of the natural lightening, multiplies the use of close-ups: it enhances the protagonists’ emotions and accentuates the closeness of on-screen visual space. Only one long shot by the sea, brings a space of breathing for the protagonists, they can dance and move freely.

While these women live under the curfew and the surveillance of Madame Osmane, Sakina (Madame Osmane’s daughter) escapes with the tenant Yasmine to go out and vent their frustrations after tensions occurred during a wedding attended by all the women of the house. At the wedding, Madame Osmane met the mother of Sakina’s fiancé and cancelled the engagement because the mother is part of a lower social class. Yasmine, a French-born Algerian, has discovered at the wedding that her husband has a second wife and a son. At the end of the film Sakina dies, shot at a faux barrage–– a checkpoint established by terrorists. However Madame Osmane believes that her daughter was in fact shot by the military at the checkpoint. Madame Osmane’s husband, who left for France, comes back to bury his daughter.

As a mujahida, Madame Osmane does not conform to the nationally constructed myth of mujahidates. Historian Ryme Seferdjeli describes how the mujahidates are portrayed as a ‘monolithic group in contrast to male combatants and reduced to the status of a single female figure who is defined almost exclusively by her gender and nationalist identity’.[54] Madame Osmane is a bourgeois figure who trades on her status and privileges as a mujahida to acquire wealth. She is only concerned with money, property, and seems to be far removed from national concerns.[55] Madame Osmane’s husband, a mujahid, a man she chose to marry while she was fighting, leaves her and chooses France, the nation that they were fighting against. The husband’s betrayal is twofold: he betrays Madame Osmane, his wife, and also his nation in order to join his mistress––France. He also represents the elite who were able to leave for France when terrorism erupted and were granted a visa, which was difficult at that time since France restricted the access to its territory only favouring business men and members of the nomenklatura.[56]

Madame Osmane perceives herself as being from a higher social class and this is reflected in the way she talks about the mother of her daughter’s fiancé. She speaks about her with contempt because she is a traditional woman, in a traditional outfit, and has a washm––a traditional tattoo that old women used to have.[57] The irony is that the tattoo is dismissed, both by Islamists as not complying with Islamic precepts that forbid any symbols (many of the tattoos are crosses), and by modernists, who view it as inscribed in old traditions. It cannot be said that Madame Osmane is a modernist. She is a conservative figure who disapproves of inter-class marriage. She even warns Yasmine against returning to France where she would have a lower social status than in Algeria: ‘tu vas faire quoi? Caissière?’ (What will you do? Cashier?).

French, in the film, is therefore associated with urban upper-middle class women who use it for socialisation and as a social marker.[58]

The final scene, that I will discuss, is a pertinent illustration of the relationships between gender, language and violence. Army officials bring Sakina’s coffin to the house. The shot is positioned from outside the house, from the location where the coffin is laid on the ground. The bright sun is juxtaposed with the tragic situation. One of the officials asks if this is Bouchama’s house (Bouchama is Madame Osmane’s husband’s name), and the maid Meriem replies: ‘non, ici c’est la maison Osmane’ (no, this is Osmane’s house). The official reads the statement about Sakina’s death, as a medium long shot displays the characters: the inhabitants of the house are gathered on one side, standing by the door; Madame Osmane’s husband stands on the other side, on the road, with the military officials––which implies that he is on ‘their side’. This is confirmed when Madame Osmane’s husband signs the death certificate of his daughter, which validates the official version of Sakina’s death: that the terrorists murdered her. Madame Osmane dismisses this version and accuses her husband of cowardice. She suggests that the military have the power to re-construct the facts to which her husband is subservient. The aforementioned panning is the only medium close-up in which Moknèche privileges male presence. In subsequent shots, men are disregarded, relegated to a second plane and are gradually removed from the frame space, pushed to its margins. Madame Osmane decides she wants to open the coffin but the State representatives refuse to let her; she threatens them with her gun, shouting in French: ‘vous êtes des bourricots’ (you are donkeys), and then fires her gun into the air.[59]

In this final scene Madame Osmane users language to impose her authority, accompanied by her act of firing the gun. Moknèche gives Madame Osmane total control of the space outside the house, and she rallies her tenants to her side. Madame Osmane resurrects her mujahida past in an unexpected way: both the gun and the French language are left over from the colonial period, which is also the anti-colonial period; and she uses both to liberate herself from the power of the Algerian authorities and from the diktat of her husband. And of course, Moknèche may be said to use French in the same way: the film has almost no trace of Standard Arabic or darija, and the film uses French as a common language that reconnects the present with the colonial past.

IV. Conclusion: what did our ‘mothers’ do?

The three films analysed in this essay expose contrasting experiences, perceptions and subjectivities in relation to the violence women endured during the black decade. Sociolinguist Reem Bassiouney remarks that in times of conflict linguistic ideologies are used as ‘political, religious or social weapons’.[60] Bassiouney’s remark is key to the study of these films: the use of language carries ideological implications in relation to the black decade narrative. The exclusion of Modern Standard Arabic in the films marks an ideological posture: these films distance themselves from the official language and also from the official narrative. The three films construct an alternative narrative that is grounded in their use of different languages: French, darija and combinations of the two, are deployed in such a way as to communicate the particular experiences of women dealing with violence.

The use of French by women corresponds with greater power for women and freedom from both state and patriarchal power, while the use of darija leaves women subject to the situation in which they live. In Le Harem de Madame Osmane French allows Madame Osmane to assert power––Arabic is absent from the film. French is also associated with higher social status and more liberal, western manners. However, exclusive use of French also serves as a marker of cultural and ideological separateness as Le Harem de Madame Osmane depicts the division of Algeria along parallel lines of class and language. Violence is not acknowledged at the beginning of Le Harem de Madame Osmane; it is only at the end that Madame Osmane becomes conscious of the situation and rejects the official state account of her daughter’s death. The use of French paradoxically reinforces the mujahida figure, which, in Le Harem de Madame Osmane and Barakat!, is presented as a strong, determined, and independent woman.

The use of darija anchors the film in authenticity, as if the use of darija alone were a guarantee of the truthfulness of the film’s events. However, Rachida is barred from asserting power: darija only allows her to assert her identity, her ideology and her Algerian-ness. Code switching––the mixing of the two un-official languages, darija and French––becomes a language in itself, one that is capable of encompassing antagonistic ideologies and transcending social classes. Just as Moknèche observed that French is an Algerian language, so the same can be said about code switching.

The three films construct an image of the Algerian woman who has stood against Islamists, an image which, prior to these films, the French media was primarily responsible for disseminating. French publishers edited books that described women’s experiences with Islamists and debates and TV channels organized discussions with Algerian women about their experiences during the black decade. The films indicate that women criticized the state’s actions and accentuate the idea that women and Islamists were in ‘diametric opposition’, but the reality was and is more complex.[61] Fériel Lalami-Fatès posits that, in resisting the Islamists, women’s associations were co-opted by the state and made to renounce their ideals, becoming less critical of the state’s actions.[62] An Islamic feminist movement has risen in the 1990s, and women supported the political ideologies of the Islamic Party. These films scarcely recognise that some women were favourably disposed towards Islamist views. Only perhaps the woman of the hijab in Rachida is seen to represent this point of view.

The three films also question the future of Algeria and ask what did the ‘mothers’ leave to their ‘daughters’? In Le Harem de Madame Osmane, the daughter dies and this is only the beginning of the tragedy to come for Algeria. As such Le Harem de Madame Osmane suggests a dim future for Algeria. Rachida recovers an identity and makes use of her mother’s past experiences, but she is the one who will reconstruct the future while her mother remains marginalized. In Barakat!, however, the mother figure is still present and she is the one who will continue the fight and inspire her daughter figure, Amel, suggesting perhaps that the situation will improve if the younger generation of women is able

[1] Benjamin Stora, La Guerre invisible: Algérie, années 90 (Paris: Presses de Sciences Po: 2001), p. 7.

[2] Mujahidates were nurses, messengers or posed bombs in urban areas such as cafes.

[3] Abdelkader Cheref, ‘Engendering or Endangering Politics in Algeria? Salima Ghezali, Louisa Hanoune, and Khalida Messaoudi’, Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 2 (2006), 60-85 (p. 68).

[4] Pan-Arabism was a cultural and political project aimed at unifying the Arab countries. The project was furthered by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser in the 1950s who equated pan Arabism with Arab nationalism, and promoted the political union of Arab states.

[5] Mohamed Benrabah, Language Conflict in Algeria: From colonialism to post-independence (Bristol: Multilingual Matters, 2013), p. 383.

[6] Catherine Miller, ‘Linguistic Policies and the Issue of Ethno-Linguistic Minorities in the Middle East’, in Islam in the Middle East Studies: Muslims and Minorities, ed. by Akira, Usuki and Hiroshi Kato (Osaka: National Museum of Ethnology, 2003), pp. 149–174 (p.150).

[7] Cheira Belguellaoui, ‘Contemporary Algerian Filmmaking: From ‘Cinéma National’ to ‘Cinéma De L’urgence'(Mohamed Chouikh, Merzak Allouache, Yamina Bachir-Chouikh, Nadir Moknèche)’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Florida State University, 2007), p. 134.

[8] Both films were popular successes upon their release in Algeria, particularly Omar Gatlato since it described the everyday life of a group of young men, and the film used the specific dialect of Algiers. Omar Gatlato attracted over a million of viewers in 1976. Director Lahkhdar Hamina won the Cannes film festival in 1975 and his second feature received international awards.

[9] During the black decade the Casbah of Algiers was the place of many terrorist attacks but also the place where Islamists were hiding. This is reminiscent of the anti-colonial struggle when the combatants hid in the Casbah, especially during the ‘Battle of Algiers’.

[10] <http://www.euromedcafe.org/interview.asp?lang=ing&documentID=696 > [accessed 12 December 2014], < http://ar.qantara.de/content/mqbl-m-lmkhrj-ymyn-bshyr-shwykh-lkl-tryqth-lkhs-fy-ltml-m-lkhsr-wlhzn> [accessed 12 December 2014].

[11] Olivier Barlet, ‘Interview with Yamina Bachir-Chouikh’, Africultures, 26 September 2002, <http://www.africultures.com/php/index.php?nav=article&no=5607#sthash.UGA9WMCm.dpuf> [accessed 12 December 2014].

[12] Yacine Idjer, ‘Cinémathèque Rachida, un autre regard sur le film’, Info Soir, 05 August 2003 <http://www.djazairess.com/fr/infosoir/1751> [accessed 25 January 2015]

[13] ‘Sourat’ Al Maraa fi film Rachida dalala similogia’ (The image of the woman in the film Rachida: semiology of a symbol’), Al Hiwar, 05 December 2008 <http://www.djazairess.com/elhiwar/7550> [accessed 25 January 2015].

[14] ‘Sourat’ Al Maraa fi film Rachida dalala similoogia j 3’ (The image of the woman in the film Rachida: semiology of a symbol- third part’, Al Hiwar, 19 December 2008 < http://www. djazairess.com.elhiwar/80 73> [accessed 25 January 2015].

[15] Alger la Blanche is the name given to Algiers for the white colour of the buildings of the Casbah––the Muslim quarter of Algiers under French colonial rule.

[16] Abdulkafi Albirini, ‘The Sociolinguistic Functions of Codeswitching between Standard Arabic and Dialectal Arabic’, Language in Society, 40 (2011), 537–562 (p. 539).

[17] Farida Abu-Haidar, ‘Arabization in Algeria’, International Journal of Francophone Studies, 3 (2000), 151-163 (p. 161).

[18] Susan Slyomovics, ‘”Hassiba Ben Bouali, If You Could See Our Algeria”: Women and Public Space in Algeria’, Middle East Report, 92 (1995), 8-13 (p. 10).

[19] Rod Skilbeck, ‘The Shroud Over Algeria: Femicide, Islamism and the Hijab’, Journal of Arabic, Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies, 2(1995), 43-54 <https://www.library. cornell.edu/colldev/mideast /shroud.htm> [accessed 25 January 2015].

[20] Yasmine Ben, ‘Bahia Rachedi, Elle fera le rituel de la Omra, portera le voile et se consacrera à l’humanitaire’, Le Maghreb, 02 July 2011.

[21] James Bennett, ‘The Television Personality System: Televisual Stardom Revisited after Film Theory’, Screen, 1 (2008), 32-50 (p. 35).

[22] Ibid., p. 35.

[23] Benrabah, p. 147.

[24] National reconciliation identifies the laws and process launched in1999. It aimed at reintegrating into civilian life those who have renounced armed violence or were involved in network support to terrorist groups, but were not charged with blood crimes.

[25] Sahraoui’s documentaries were mainly funded by by French-German television Arte, and were subtitled in French, when interviews were conducted in Berber language.

[26]Melbroune International Film Festival website <http://miff.com.au/festival-archive/film/12306> [accessed 11 November 2014].

[27] The slogan used by demonstrators in the street to end the cycle of killings between two political factions of the GPRA (Gouvernement Provisoire de la Révolution Algérienne) and the FLN (Front de Libération Nationale).

[28] maquis designates the French word for the bush, as utilized by underground or guerilla fighters. During the Algerian war the fighters used to hide in the maquis where military camps were established. The technique was adopted by the Islamic armed factions.

[29] See articles of Hind O, ‘Deux femmes dans la tourmente. Projection de Barakat! de Djamila Sahraoui à El Mougar’, L’Expression, 11 November 2006, Yasmine Ben, ‘Une légèreté à vous couper le souffle! Sortie de Barakat! de Djamila Sahraoui’, Le Maghreb, 14 November 2006 http: //www.djazairess.com /fr/lemaghreb/173> [accessed 02 February 2015].

[30] Zahia Mancer, ‘Al Mahzila tataoucel Number One al yaoum bil Jazair wa Barakat! youtouaj bi dhahb fi Dubai’ (‘The farce continues: Number One today in Algeria, and Barakat! crowned with gold in Dubai’, Achourouk , 18 December 2006 <http://www.echoroukonline.com/ara/?news=9900> [accessed 02 February 2015].

[31] Fatiha Bourouina, ‘Film Barakat! Youajihou ashrass intiqadat fi El Jazair baa’da tasnifihi fi khanet ‘al cinema ‘al coulounialiya’’ (‘The movie “Barakat” facing the fiercest criticism in Algeria after coined as a ‘colonial cinema’’), Al Riyadh, 25 December 2006, <http://www.alriyadh.com/211850> [accessed 02 February 2015].

[32] Mancer, Ben, O.

[33] Hind O, ‘Deux femmes dans la tourmente. Projection de Barakat! de Djamila Sahraoui à El Mougar’, L’Expression, 11 November 2006.

[34] Walid Mebarek, ‘Djamila Sahraoui. Réalisatrice de Barakat: ‘Les choses ressortent’’, El Watan, 15 November 2006.

[35] Yacine Idjer, ‘Cinéma «Barakat» en avant-première: deux femmes chez les terroristes’, Info Soir, 10 November 2006< http://www.djazairess.com/fr/infosoir/55698> [accessed 05 February 2015].

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ben, Le Maghreb.

[38] Foundou is an arabized name of French ‘Fond deux’ that refers to the mine where Alla’s father worked under French colonial rule.

[39] Monica Heller, Code switching: Anthropological and Sociolinguistic Perspectives (New York, London, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter: 1988), p. 8.

[40] Ibid., p. 8.

[41] Anne-Emmanuelle Berger, ‘The Newly Veiled Woman: Irigaray, Specularity, and the Islamic Veil’, Diacritics, 1 (1998), 93-119 (p. 106). Berger makes use in her article of Djamila Saadi’s work : ‘Des Femmes à mots voilés’, Penser l’Algérie Intersignes, 10 (1995), 169-80.

[42] Ibid., p. 106.

[43] Frantz Fanon, ‘L’Algérie se dévoile’, L’an V de la révolution algérienne (Paris: Maspéro, 1960). For a complete analysis of Fanon’s discussion of the haïk, see Berger, pp.106-109.

[44] Berger, p. 106.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Gilles, Kepel, ‘Islamism and the State in Algeria and Egypt’, Daedelus, 124 (1995), 109-127

(p. 121).

[47] Lahouari Addi, ‘Les Intellectuels qu’on assassine’, Esprit, 208 (1995), 130-138 (p. 131).

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid, p. 137.

[51] Gérard Le Fort, ‘Avec Viva Laldjérie, Nadir Moknèche regarde son pays droit dans les yeux’, Libération, 7 April 2004.

[52] Huis clos is a French expression that could be translated as ‘behind closed doors’. It is used here in a sense intended to transmit the closeness of the action.

[53] The word harem is derived from Arabic harem which means women and designates the space where women and concubines live. It has been later associated can also mean ‘haram’, ‘forbidden’.

[54] Ryme Seferdjeli, ‘Rethiking the history of the mujahidat during the Algerian war’, Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, 2 (2012), 238-255 (p. 246).

[55] The status of mujahidin allowed privileges in post-independence Algeria such as housing, medical care, and tax reductions on imported goods. A Ministry of Mujahidin was established after independence.

[56] Esprit, ‘La Politique française de coopération vis-à-vis de l’Algérie: un quiproquo tragique’, Esprit, 208 (1995), 153-161 (p. 160).

[57] Although the significance of the tattoos is not known, as a tradition women wear it on their forehead, allegedly as a marker for femininity. It may also have been encouraged by men who were also protective of women during the colonial era, or used to mark who the tribe women belonged to, to protect them or to differentiate social classes. T. Rivière and J. Faublée, ‘Les Tatouages des Chaouia de l’Aurès’, Journal de la société des Africanistes, 12 (1942), 67-80 <http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/jafr_0037-9166_1942_num_12_1_2525#> [accessed 11 November 2014].

[58] Reem Bassiouney, Arabic languages and linguistics (Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 2012), p. 124.

[59] Bourricot is a common word in Algeria: a translation of donkey (hmar), it is used as an insult for dumb people.

[60] Reem Bassiouney, Arabic languages and linguistics (Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 2012), p. 203.

[61] Constance N. Stadler, ‘Democratisation Reconsidered: the Transformation of Political Culture in Algeria’, The Journal of North African Studies, 3 (1998), 25-45 (p. 34).

[62] Fériel Lalami-Fatès, ‘Les Associations de femmes algériennes face à la menace islamiste’, Esprit, 208 (1995), 126-129 (p. 127).

Bibliography

Abu-Haidar, Farida, ‘Arabization in Algeria’, International Journal of Francophone Studies, 3 (2000), 151-163

Addi, Lahouari, ‘Les Intellectuels qu’on assassine’, Esprit, 208 (1995), 130-138

Albirini, Abdulkafi, ‘The sociolinguistic Functions of Code switching between Standard Arabic and Dialectal Arabic’, Language in Society, 40 (2011), 537–562

Barlet, Olivier, ‘Interview with Yamina Bachir-Chouikh’, Africultures, 26 September 2002, <http://www.africultures.com/php/index.php?nav=article&no=5607#sthash.UGA9WMCm.dpuf> [accessed 12 December 2014]

____________, ‘Le Harem de Mme Osmane de Nadir Moknèche’, Africultures, 01 September 2009 <http://www.africultures.com/php/?nav=article&no=1507> [accessed 28 December 2014]

Belguellaoui, Cheira,‘ Contemporary Algerian Filmmaking: From “Cinéma National” to “Cinéma De L’urgence”(Mohamed Chouikh, Merzak Allouache, YaminaBachir- Chouikh, Nadir Moknèche)’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Florida State University, 2007)

Ben, Yasmine, ‘Bahia Rachedi, Elle fera le rituel de la Omra, portera le voile et se consacrera à l’humanitaire’, Le Maghreb, 02 July 2011.

Bennett, James ‘The Television Personality System: Televisual Stardom Revisited after Film Theory’, Screen, 1 (2008), 32-50

Benrabah, Mohamed, Language Conflict in Algeria: From colonialism to post-independence (Bristol: Multilingual Matters, 2013).

Berger, Anne-Emmanuelle, ‘The Newly Veiled Woman: Irigaray, Specularity, and the Islamic Veil’, Diacritics, 1 (1998), 93-119

Bourouina, Fatiha ‘Film Barakat! Youajihou ashrass intiqadat fi El Jazair baa’da tasnifihi fi khanet ‘al cinema ‘al coulounialiya’’ (‘The movie “Barakat” facing the fiercest criticism in Algeria after coined as a ‘colonial cinema’’), Al Riyadh, 25 December 2006 <http://www.alriyad h.com/211850> [accessed 02 February 2015].

Cheref, Abdelkader, ‘Engendering or Endangering Politics in Algeria? Salima Ghezali, Louisa Hanoune, and Khalida Messaoudi’, Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 2 (2006), 60-85

Esprit, ‘La Politique française de coopération vis-à-vis de l’Algérie: un quiproquo tragique’, Esprit, 208 (1995), 153-161

Fanon, Frantz ‘L’Algérie se dévoile’, L’an V de la révolution algérienne (Paris: Maspéro, 1960)

H, G, ‘Yasin Temlali: «Les œuvres traitées dans cet ouvrage alimentent le débat politique actuel»’, La Tribune, 10 July 2011, < http://www.djazairess.com/fr/latribune/54603> [accessed 12 December 2014]

Heller, Monica, Code switching: Anthropological and Sociolinguistic Perspectives (New York, London, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1988)

Idjer, Yacine, ‘Cinémathèque Rachida, un autre regard sur le film’, Info Soir, 05 August 2003 <http://www.djazairess.com/fr/infosoir/1751> [accessed 25 January 2015]

–––––––––––, ‘Cinéma «Barakat» en avant-première: deux femmes chez les terroristes’, Info Soir, 10 November 2006 < http://www.djazairess.com/fr/infosoir/55698> [accessed 05 February 2015].

Kepel, Gilles, ‘Islamism and the State in Algeria and Egypt’, Daedelus, 124 (1995), 109-127

Lalami-Fatès, Fériel, ‘Les Associations de femmes algériennes face à la menace islamiste’, Esprit, 208 (1995), 126-129

Le Fort, Gérard, ‘Avec Viva Laldjérie, Nadir Moknèche regarde son pays droit dans les yeux’, Libération, 7 April 2004.

Mancer, Zahia, ‘Al Mahzila tataoucel Number One al yaoum bil Jazair wa Barakat! youtouaj bi dhahb fi Dubai’ (‘The farce continues: Number One today in Algeria, and Barakat! crowned with gold in Dubai’), Achourouk , 18 December 2006 <http://www. echoroukonline.com/ara/? news=9900> [accessed 02 February 2015]

Mebarek, Walid, ‘Djamila Sahraoui. Réalisatrice de Barakat: ‘Les choses ressortent’’, El Watan, 15 November 2006.

O, Hind, ‘Deux femmes dans la tourmente. Projection de Barakat! de Djamila Sahraoui à El Mougar’, L’Expression, 11 November 2006

Rivière T. and Faublée J., ‘Les Tatouages des Chaouia de l’Aurès’, Journal de la Société des Africanistes, 12 (1942), 67- 80 <http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/Jafr_0037-9166_1942_num_12_1_2525#> [accessed 11 November 2014]

Skilbeck, Rod, ‘The Shroud Over Algeria: Femicide, Islamism and the Hijab’, Journal of Arabic, Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies, 2(1995), 43-54 <https://www.library. cornell.edu/colldev/mideast /shroud.htm> [accessed 25 January 2015].

Soltane, Amira, ‘Pourquoi la chaîne 2M a diffusé le film Harragas?’, L’Expression, 9 October 2010

Stadler, Constance N., ‘Democratisation reconsidered: the transformation of political culture in Algeria’, The Journal of North African Studies, 3 (1998), 25-45

Seferdjeli, Ryme ‘Rethiking the history of the mujahidat during the Algerian war’, Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, 2 (2012), 238-255

Stora, Benjamin, La Guerre invisible: Algérie, années 90 (Paris : Presse de Sciences Po, 2001)

Slyomovics, Susan, ‘”Hassiba Ben Bouali, If You Could See Our Algeria”: Women and Public Space in Algeria’, Middle East Report, 92 (1995), 8-13

Websites

Melbroune International Film Festival website http://miff.com.au/festival-archive/film/12306 [accessed 11 November 2014]

Sourat’ Al Maraa fi film Rachida dalala similogia’ (The image of the woman in the film Rachida: semiology of a symbol ), Al Hiwar, 05 December 2008 http://www.djazairess.com/elhiwar/7550 [accessed 25 January 2015].

‘Sourat’ Al Maraa fi film Rachida dalala similoogia j 3’ (The image of the woman in the film Rachida: semiology of a symbol third part’, Al Hiwar, 19 December 2008 < http://www. djazairess.com.elhiwar/80 73> [accessed 25 January 2015].

< http://www.babelmed.net/letteratura/236-algeria/6091-litt-rature-alg-rienne-la-proximit-du-drame.html> [accessed 12 November 2014]

< http://www.babelmed.net/arte-e-spettacolo/116-algeria/2930-chronique-de-braises-du-cin-ma-alg-rien-entretien-avec-salim-aggar.html>[accessed 12 November 2014]

http://www.euromedcafe.org/interview.asp?lang=ing&documentID=696

[accessed 12 December 2014]