“Human creativity and human capacity is limitless,” said the Bangladeshi economist Muhammad Yunus to a darkened room full of rapt Austrian elites. The setting was TEDx Vienna, and Yunus’s address bore all the trademark features of TED’s missionary version of technocratic idealism. “We believe passionately in the power of ideas to change attitudes, lives and, ultimately, the world,” goes the TED mission statement, and this philosophy is manifest in the familiar form of Yunus’s talk (TED.com). The lighting was dramatic, the stage sparse, and the speaker alone on stage, with only his transformative ideas for company. The speech ends with the zealous technophilia that, along with the minimalist stagecraft and quaint faith in the old-fashioned power of lectures, defines this peculiar genre. “This is the age where we all have this capacity of technology,” Yunus declares: “The question is, do we have the methodology to use these capacities to address these problems?… The creativity of human beings has to be challenged to address the problems we have made for ourselves. If we do that, we can create a whole new world—we can create a whole new civilization” (Yunus 2012). Yunus’s conviction that now, finally and for the first time, we can solve the world’s most intractable problems, is not itself new. Instead, what TED Talks like this offer is a new twist on the idea of progress we have inherited from the nineteenth century. And with his particular focus on the global South, Yunus riffs on a form of that old faith, which might seem like a relic of the twentieth: “development.” What is new, then, about Yunus’s articulation of these old faiths? It comes from the TED Talk’s combination of prophetic individualism and technophilia: this is the ideology of “innovation.”

“Innovation”: a ubiquitous word with a slippery meaning. “An innovation is a novelty that sticks,” writes Michael North in Novelty: A History of the New, pointing out the basic ontological problem of the word: if it sticks, it ceases to be a novelty. “Innovation, defined as a widely accepted change,” he writes, “thus turns out to be the enemy of the new, even as it stands for the necessity of the new” (North 2013, 4). Originally a pejorative term for religious heresy, in its common use today “innovation” is used a synonym for what would have once been called, especially in America, “futurity” or “progress.” In a policy paper entitled “A Strategy for American Innovation,” then-President Barack Obama described innovation as an American quality, in which the blessings of Providence are revealed no longer by the acquisition of territory, but rather by the accumulation of knowledge and technologies: “America has long been a nation of innovators. American scientists, engineers and entrepreneurs invented the microchip, created the Internet, invented the smartphone, started the revolution in biotechnology, and sent astronauts to the Moon. And America is just getting started” (National Economic Council and Office of Science and Technology Policy 2015, 10).

In the Obama administration’s usage, we can see several of the common features of innovation as an economic ideology, some of which are familiar to students of American exceptionalism. First, it is benevolent. Second, it is always “just getting started,” a character of newness constantly being renewed. Third, like “progress” and “development” have been, innovation is a universal, benevolent abstraction made manifest through material, economic accomplishments. But even more than “progress,” which could refer to political and social accomplishments like universal suffrage or the polio vaccine, or “development,” which has had communist and social democratic variants, innovation is inextricable from the privatized market that animates it. For this reason, Obama can treat the state-sponsored moon landing and the iPhone as equivalent achievements. Finally, even if it belongs to the nation, the capacity for “innovation” really resides in the self. Hence Yunus’s faith in “creativity,” and Obama’s emphasis on “innovators,” the protagonists of this heroic drama, rather than the drama itself.

This essay explores the individualistic, market-based ideology of “innovation” as it circulates from the English-speaking first world to the so-called third world, where it supplements, when it does not replace, what was once more exclusively called “development.” I am referring principally to projects that often go under the name of “social innovation” (or, relatedly, “social entrepreneurship”), which Stanford University’s Business School defines as “a novel solution to a social problem that is more effective, efficient, sustainable, or just than current solutions” (Stanford Graduate School of Business). “Social innovation” often advertises itself as “market-based solutions to poverty,” proceeding from the conviction that it is exclusion from the market, rather than the opposite, that causes poverty. The practices grouped under this broad umbrella include projects as different the micro-lending banks, for which Yunus shared the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize; smokeless, cell-phone charging cookstoves for South Asia’s rural peasantry; latrines that turn urine into electricity, for use in rural villages without running water; and the edtech academic and TED honoree Sugata Mitra’s “self-organized learning environment” (SOLE), which appears to consist mostly of giving internet-enabled laptops to poor children and calling it a day.

The discourse of social innovation is a theory about economic process and also a story of the (first-world) self. The ideal innovator that emerges from the examples to follow is a flexible, socially autonomous individual, whose creativity and prophetic vision, nurtured by the market, can refashion social inequalities as discrete “problems” that simply await new solutions. Guided by a faith in the market but also shaped by the austerity that has slashed the budgets of humanitarian and development institutions worldwide, social innovation ideology marks a retreat from the social vision of development. Crucially, the ideologues of innovation also answer a post-development critique of Western arrogance with a generous, even democratic spirit. That is, one of the reasons that “innovation” has come to supersede “development” in the vocabulary of many humanitarian and foreign aid agencies is that innovation ideology’s emphasis on individual agency serves as a response to the legitimate charges of condescension and elitism long directed at Euro-American development agencies. But compromising the social vision of development also means jettisoning the ideal of global equality that, however deluded, dishonest, or self-serving it was, also came with it. This brings us to a critical feature of innovation thinking that is often disguised by the enthusiasm of its tech-economy evangelizers: it is in fact a pessimistic ideal of social change. The ideology of innovation, with its emphasis on processes rather than outcomes, and individual brilliance over social structures, asks us to accommodate global inequality, rather than challenge it. It is a kind of idealism, therefore, well suited to our dispiriting neoliberal moment, where the sense of possibility seems to have shrunk.

My objective is not to evaluate these efforts individually, nor even to criticize their practical usefulness as solution-oriented projects (not all of them, anyway). Indeed, in response to the difficult, persistent question, “What is the alternative?” it is easy, and not terribly helpful, to simply answer “world socialism,” or at least “import-substitution industrialization.” My objective is perhaps more modest: to define the ideology of “innovation” that undergirds these projects, and to dissect the Anglo-American ego-ideal that it circulates. As an ideology, innovation is driven by a powerful belief, not only in technology and its benevolence, but in a vision of the innovator: the autonomous visionary whose creativity allows him to anticipate and shape capitalist markets.

An Orthodoxy of Unorthodoxy: Innovation, Revolution, and Salvation

Given the immodesty of the innovator archetype, it may seem odd that innovation ideology could be considered pessimistic. On its own terms, of course, it is not; but when measured against the utopian ambitions and rhetoric of many “social innovators” and technology evangelists, their actual prescriptions appear comparatively paltry. Human creativity is boundless, and everyone can be an innovator, says Yunus; this is the good news. The bad news, unfortunately, is that not everyone can have indoor plumbing or public lighting. Consider the “pee-powered toilet” sponsored by the Gates Foundation. The outcome of inadequate sewerage in the underdeveloped world has not been changed; only the process of its provision has been innovated (Smithers 2015). This combination of evangelical enthusiasm and piecemeal accommodation becomes clearer, however, when we excavate innovation’s tangled history, which by necessity, the word seems at first glance to lack entirely.

For most of its history, the word has been synonymous with false prophecy and dissent: initially, it was linked to deceitful promises of deliverance, either from divine judgment or more temporal forms of punishment. For centuries, this was the most common usage of this term. The charge of innovation warned against either the possibility or the wisdom of remaking the world, and disciplined those “fickle changelings and poor discontents,” as the King says in Shakespeare’s Henry IV, grasping at “hurly-burly innovation.” Religious and political leaders tarred self-styled prophets or rebels as heretical “innovators.” In his 1634 Institution of the Christian Religion, for example, John Calvin warned that “a desire to innovate all things without punishment moveth troublesome men” (Calvin 1763, 716). Calvin’s notion that innovation was both a political and theological error reflected, of course, his own jealously kept share of temporal and spiritual authority. For Thomas Hobbes, “innovators” were venal conspirators, and innovation a “trumpet of war and sedition.” Distinguishing men from bees—which Aristotle, Hobbes says, wrongly considers a political animal like humans—Hobbes laments the “contestation of honour and preferment” that plagues non-apiary forms of sociality. Bees only “talk” when and how they have to; men and women, by contrast, chatter away in their vanity and ambition (Hobbes 1949, 65-67). The “innovators” of revolutionary Paris, Edmund Burke thundered later, “leave nothing unrent, unrifled, unravaged, or unpolluted with the slime of their filthy offal” (1798, 316-17). Innovation, like its close relative “revolution,” was upheaval, destruction, the reversal of the right order of things.

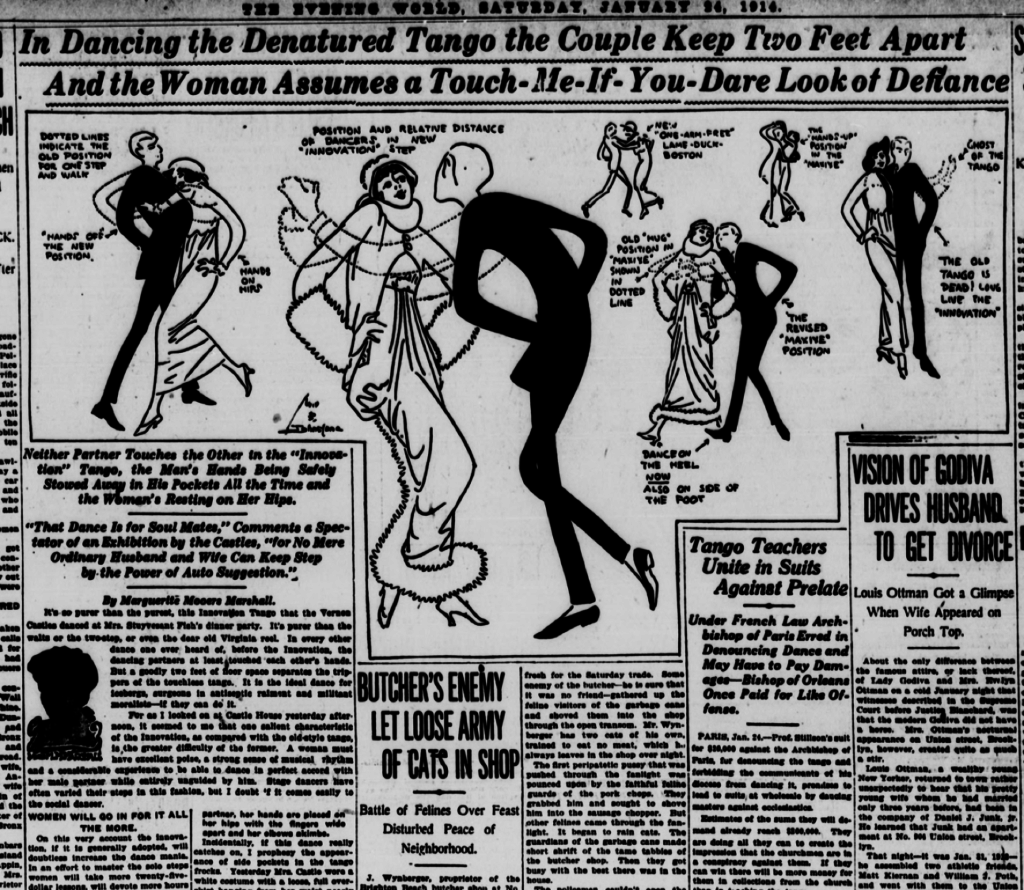

As Godin (2015) shows in his history of the concept in Europe, in the late nineteenth century “innovation” began to be recuperated as an instrumental force in the world, which was key to its transformation into the affirmative concept we know now. Francis Bacon, the philosopher and Lord Chancellor under King James I, was what we might call an “early adopter” of this new positive instrumental meaning. How, he asked, could Britons be so reverent of custom and so suspicious of “innovation,” when their Anglican faith was itself an innovation? (Bacon 1844, 32). Instead of being an act of sudden renting, rifling, and heretical ravaging, “innovation” became a process of patient material improvement. By the turn of the last century, the word had mostly lost its heretical associations. In fact, “innovation” was far enough removed from wickedness or malice in 1914 that the dance instructor Vernon Castle invented a modest American version of the tango that year and named it “the Innovation.” The partners never touched each other in this chaste improvement upon the Argentine dance. “It is the ideal dance for icebergs, surgeons in antiseptic raiment and militant moralists,” wrote Marguerite Marshall (1914), a thoroughly unimpressed dance critic in the New York Evening World. “Innovation” was then beginning to assume its common contemporary form in commercial advertising and economics, as a synonym for a broadly appealing, unthreatening modification of an existing product.

Two years earlier, the Austrian-born economist Joseph Schumpeter published his landmark text The Theory of Economic Development, where he first used “innovation” to describe the function of the “entrepreneur” in economic history (1934, 74). For Schumpeter, it was in the innovation process that capitalism’s tendency towards tumult and creative transformation could be seen. He understood innovation historically, as a process of economic transformation, but he also singled out an innovator responsible for driving the process. In his 1942 book Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, Schumpeter returned to the idea in the midst of war and the threat of socialism, which gave the concept a new urgency. To innovate, he wrote was “to reform or revolutionize the pattern of production by exploiting an invention or, more generally, an untried technological possibility for producing a new commodity or producing an old one in a new way, by opening up a new source of supply of materials or a new outlet for products, by reorganizing an industry and so on” (Schumpeter 2003, 132). As Schumpeter goes on to acknowledge, this transformative process is hard to quantify or professionalize. The elusiveness of his theory of innovation comes from a central paradox in his own definition of the word: it is both a world-historical force and a quality of personal agency, both a material process and a moral characteristic. It was a historical process embodied in heroic individuals he called “New Men,” and exemplified in non-commercial examples, like the “expressionist liquidation of the object” in painting (126). To innovate was also to do, at the local level of the production process, what Marx and Engels credit the bourgeoisie as a class for accomplishing historically: revolutionizing the means of production, sweeping away what is old before it can ossify. Schumpeter told a different version of this story, though. For Marx, capitalist accumulation is a dialectical historical process, but what Schumpeter called innovation was a drama driven by a particular protagonist: the entrepreneur.

In a sympathetic 1943 essay about Schumpeter theory of innovation, the Marxist economist Paul Sweezy criticized the centrality Schumpeter gave to individual agency. Sweezy’s interest in the concept is unsurprising, given how Schumpeter’s treatment of capitalism as a dynamic but destructive historical force draws upon Marx’s own. It is therefore not “innovation” as a process to which Sweezy objects, but the mythologized figure of the entrepreneurial “innovator,” the social type driving the process. Rather than a free agent, powering the economy’s inexorable progress, “we may instead regard the typical innovator as the tool of the social relations in which he is enmeshed and which force him to innovate on pain of elimination,” he writes (Sweezy 1943, 96). In other words, it is capital accumulation, not the entrepreneurial function, and certainly not some transcendent ideal of creativity and genius, that drives innovation. And while the innovator (the successful one, anyway) might achieve a pantomime of freedom within the market, for Sweezy this agency is always provisional, since innovation is a conditional economic practice of historically constituted subjects in a volatile and pitiless market, not a moral quality of human beings. Of course, Sweezy’s critique has not won the day. Instead, a particularly heroic version of the Schumpeterian sense of innovation as a human, moral quality liberated by the turbulence of capitalist markets is a mainstream feature of institutional life. An entire genre of business literature exists to teach the techniques of “managing creativity and innovation in the workplace” (The Institute of Leadership and Management 2007), to uncover the “map of innovation” (O’Connor and Brown 2003), to nurture the “art of innovation” (Kelley 2001), to close the “circle of innovation” (Peters 1999), to collect the recipes in “the innovator’s cookbook” (Johnson 2011), to give you the secrets of “the sorcerers and their apprentices” (Moss 2011)—business writers leave virtually no hackneyed metaphor for entrepreneurial creativity, from the domestic to the occult, untouched.

As its contemporary proliferation shows, innovation has never quite lost its association with redemption and salvation, even if it is no longer used to signify their false promises. As Lepore (2014) has argued about its close cousin, “disruption,” innovation can be thought of as a secular discourse of economic and personal deliverance. Even as the concept became rehabilitated as procedural, its deviant and heretical connotations were common well into the twentieth century, when Emma Goldman (2000) proudly and defiantly described anarchy as an “uncompromising innovator” that enraged the princes and oligarchs of the world. Its seeming optimism, which is inseparable from the disasters from which it promises to deliver us, is thus best considered as a response to a host of persistent anxieties of twenty-first-century life: economic crisis, violence and war, political polarization, and ecological collapse. Yet the word has come to describe the reinvention or recalibration of processes, whether algorithmic, manufacturing, marketing, or otherwise. Indeed, even Schumpeter regarded the entrepreneurial function as basically technocratic. As he put it in one essay, “it consists in getting things done” (Schumpeter 1941, 151).[1] However, as the book titles above make clear, the entrepreneurial function is also a romance. If capitalism was to survive and thrive, Schumpeter suggested, it needed to do more than produce great fortunes: it had to excite the imagination. Otherwise, it would simply calcify into the very routines it was charged with overthrowing. Innovation discourse today remains, paradoxically, both procedural and prophetic. The former meaning lends innovation discourse its piecemeal, solution-oriented accommodation to inequality. In this latter sense, though, the word retains some of the heretical rebelliousness of its origins. We are familiar with the lionization of the tech CEO as a non-confirming or “disruptive” visionary, who sets out to “move fast and break things,” as the famous Facebook motto went. The archetypal Silicon Valley innovator is forward-looking and rebellious, regardless of how we might characterize the results of his or her innovation—a social network, a data mining scheme, or Uber-for-whatever. The dissenting meaning of innovation is at play in the case of social innovation, as well, given its aim to address social inequalities in significant new ways. So, in spite of innovation’s implicit bias towards the new, the history and present-day use of the word remind us that its present-day meaning is seeded with its older ones. Innovation’s new secular, instrumental meaning is therefore not a break with its older, prohibited, religious connotation, but an embellishment of it: what is described here is a spirit, an ideal, an ideological rescrambling of the word’s older heterodox meaning to suit a new orthodoxy.

The Innovation of Underdevelopment: From Exploitation to Exclusion

In his 1949 inaugural address, which is often credited with popularizing the concept of “development,” Harry Truman called for “a bold new program for making the benefits of our scientific advances and industrial progress available for the improvement and growth of underdeveloped areas” (Truman 1949).[2] “Development” in U.S. modernization theory was defined, writes Nils Gilman, by “progress in technology, military and bureaucratic institutions, and the political and social structure” (2003, 3). It was a post-colonial version of progress that defined itself as universal and placeless; all underdeveloped societies could follow a similar path. As Kristin Ross argues, development in the vein of post-war modernization theory anticipated a future “spatial and temporal convergence” (1996, 11-12). Emerging in the collapse of European colonialism, the concept’s positive value was that it positioned the whole world, south and north, as capable of the same level of social and technical achievement. As Ross suggests, however, the future “convergence” that development anticipates is a kind of Euro-American ego-ideal—the rest of the world’s brightest possible future resembled the present of the United States or western Europe. As Gilman puts it, the modernity development looked forward to was “an abstract version of what postwar American liberals wished their country to be.”

Emerging as it did in the decline, and then in the wake, of Europe’s African, Asian, and American empires, mainstream mid-century writing on development tread carefully around the issue of exploitation. Gunnar Myrdal, for example, was careful to distinguish the “dynamic” term “underdeveloped” from its predecessor, “backwards” (1957, 7). Rather than view the underdeveloped as static wards of more “advanced” metropolitan countries, in other words, the preference was to view all peoples as capable of historical dynamism, even if they occupied different stages on a singular timeline. Popularizers of modernization theory like Walter Rostow described development as a historical stage that could be measured by certain material benchmarks, like per-capita car ownership. But it also required immaterial, subjective cultural achievements, as Josefina Saldaña-Portillo, Jorge Larrain, and Molly Geidel have pointed out. In his well-known Stages of Economic Growth, Rostow emphasized how achieving modernity required the acquisition of what he called “attitudes,” such as a “Newtonian” worldview and an acclimation to “a life of change and specialized function” (1965, 26). His emphasis on cultural attributes—prerequisites for starting development that are also consequences of achieving it—is an example of the development concept’s circular, often self-contradictory meanings. “Development” was both a process and its end point—a nation undergoes development in order to achieve development, something Cowen and Shenton call the “old utilitarian tautology of development” (1996, 4), in which a precondition for achieving development would appear to be its presence at the outset.

This tautology eventually circles back to what Nustad (2007, 40) calls the lingering colonial relationship of trusteeship, the original implication of colonial “development.” For post-colonial critics of developmentalism the very notion of “development” as a process unfolding in time is inseparable from this colonial relation, given the explicit or implicit Euro-American telos of most, if not all, development models. Where modernization theorists “naturalized development’s emergence into a series of discrete stages,” Saldaña-Portillo (2003, 27) writes, the Marxist economists and historians grouped loosely under the heading of “dependency theory” spatialized global inequality, using a model of “core” and “periphery” economies to counter the model of “traditional” and “modern” ones. Two such theorists, Andre Gunder Frank and Walter Rodney, framed their critiques of development with the grammar of the word itself. Like “innovation,” “development” is a progressive noun, which indicates an ongoing process in time. Its temporal and agential imprecision—when will the process ever end? Can it? Who is in charge?—helps to lend development a sense of moral and political neutrality, which it shares with “innovation.” Frank titled his most famous book on the subject The Development of Underdevelopment, the title emphasizing the point that underdevelopment was not a mere absence of development, but capitalist development’s necessary product. Rodney’s book How Europe Underdeveloped Africa did something similar, by making “underdevelop” into a transitive verb, rather than treating “underdevelopment” as a neutral condition.[3]

As Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello argue, this language of neutrality became a hallmark of European accounts of global poverty and underdevelopment after the 1960s. According to their survey of economics and development literature, the category of “exclusion” (and its opposite number, “empowerment”) and the gradual disappearance of “exploitation” from economic and humanitarian literature about poverty. No single person, firm, institution, party, or class is responsible for “exclusion,” Boltanksi and Chiapello explain. Reframing exploitation as exclusion therefore “permits identification of something negative without proceeding to level accusations. The excluded are no one’s victims” (2007, 347 & 354). Exploitation is a circumstance that enriches the exploiter; the poverty that results from exclusion, however, is a misfortune profiting no one. Consider, as an example, the mission statement of the Grameen Foundation, which Yunus founded. It remains one of the leading microlenders in the world, devoted to bringing impoverished people in the global South, especially women, into the financial system through the provision of small, low-collateral loans. “Empowerment” and “innovation” are two of its core values. “We champion innovation that makes a difference in the lives of the poor,” runs one plank of the Foundation’s mission statement (Grameen Foundation India nd). “We seek to empower the world’s poor, especially the poorest women.” “Innovation” is often not defined in such statements, but rather treated as self-evidently meaningful. Like “development,” innovation is a perpetually ongoing process, with no clear beginning or end. One undergoes development to achieve development; innovation, in turn, is the pursuit of innovation, and as soon as one innovates, the innovation thus created soon ceases to be an innovation. This wearying semantic circle helps evacuate the processes of its power dynamics, of winners and losers. As Evgeny Morozov (2014, 5) has argued about what he calls “solutionism,” the celebration of technological and design fixes approaches social problems like inequality, infrastructural collapse, inadequate housing, etc.—which might be regarded as results of “exploitation”—as intellectual puzzles for which we simply have to discover the solutions. The problems are not political; rather, they are conceptual: we either haven’t had the right ideas, or else we haven’t applied them right.[4] Grameen’s mission, to bring the world’s poorest into financial markets that currently do not include them, relies on a fundamental presumption: that the global financial system is something you should definitely want to be a part of.[5] But as Banerjee et. al (2015: 23) have argued, to the extent that microcredit programs offer benefits, they mostly accrue to already profitable businesses. The broader social benefits touted by the programs—women’s “empowerment,” more regular school attendance, and so on—were either negligible or non-existent. And as a local government official in the Indian province of Anhan Pradesh told the New York Times in 2010, microloan programs in his district had not proven to be less exploitative than their predecessors, only more remote. “The money lender lives in the community,” he said. “At least you can burn down his house” (Polgreen and Bajaj 2010).

Humanitarian Innovation and the Idea of “The Poor”

Yunus’s TED Talk and the Grameen Foundation’s mission statement draw on the twinned ideal of innovation as procedure and salvation, and in so doing they recapitulate development’s modernist faith in the leveling possibilities of technology, albeit with the individualist, market-based zeal that is particular to neoliberal innovation thinking. “Humanitarian innovation” is a growing subfield of international development theory, which, like “social innovation,” encourages market-based solutions to poverty. Most scholars date the concept to the 2009 fair held by ALNAP (Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance in Humanitarian Action), an international humanitarian aid agency that measures and evaluates aid programs. Two of its leading academic proponents, Alexander Betts and Louise Bloom of the Oxford Humanitarian Innovation Project, define it thusly:

“Innovation is the way in which individuals or organizations solve problems and create change by introducing new solutions to existing problems. Contrary to popular belief, these solutions do not have to be technological and they do not have to be transformative; they simply involve the adaptation of a product or process to context. ‘Humanitarian’ innovation may be understood, in turn, as ‘using the resources and opportunities around you in a particular context, to do something different to what has been done before’ to solve humanitarian challenges” (Betts and Bloom 2015, 4).[6]

Here and elsewhere, the HIP hews closely to conventional Schumpeterian definitions of the term, which indeed inform most uses of “innovation” in the private sector and elsewhere: as a means of “solving problems.” Read in this light, “innovation” might seem rather innocuous, even banal: a handy way of naming a human capacity for adaptation, improvisation, and organization. But elsewhere, the authors describe humanitarian innovation as an urgent response to very specific contemporary problems that are political and ecological in nature. “Over the past decade, faced with growing resource constraints, humanitarian agencies have held high hopes for contributions from the private sector, particularly the business community,” they write. Compounding this climate of economic austerity that derives from “growing resource constraints” is an environmental and geopolitical crisis that means “record numbers of people are displaced for longer periods by natural disasters and escalating conflicts.” But despite this combination of violence, ecological degradation, and austerity, there is hope in technology: “new technologies, partners, and concepts allow humanitarian actors to understand and address problems quickly and effectively” (Betts and Bloom 2014, 5-6).

The trope of “exclusion,” and its reliance on a rather anodyne vision of the global financial system as a fair sorter of opportunities and rewards, is crucial to a field that counsels collaboration with the private sector. Indeed, humanitarian innovators adopt a financial vocabulary of “scaling,” “stakeholders,” and “risk” in assessing the dangers and effectiveness (the “cost” and “benefits”) of particular tactics or technologies. In one paper on entrepreneurial activity in refugee camps, de la Chaux and Haugh make an argument in keeping with innovation discourse’s combination of technocratic proceduralism and utopian grandiosity: “Refugee camp entrepreneurs reduce aid dependency and in so doing help to give life meaning for, and confer dignity on, the entrepreneurs,” they write, emphasizing in their first clause the political and economic austerity that conditions the “entrepreneurial” response (2014, 2). Relying on an exclusion paradigm, the authors point to a “lack of functioning markets” as a cause of poverty in the camps. By “lack of functioning markets,” de la Chaux and Haugh mean lack of capital—but “market,” in this framework, becomes simply an institutional apparatus which one enters and is adjudicated on one’s merits, rather than a field of conflict in which one labors in a globalized class society. At the same time, “innovation” that “empowers” the world’s “poorest” also inherits an enduring faith in technology as a universal instrument of progress. One of the preferred terms for this faith is “design”: a form of techne that, two of its most famous advocates argue, “addresses the needs of the people who will consume a product or service and the infrastructure that enables it” (Brown and Wyatt, 2010).[7] The optimism of design proceeds from the conviction that systems—water safety, nutrition, etc.—fail because they are designed improperly, without input from their users. De la Chaux addresses how ostensibly temporary camps grow into permanent settlements, using Jordan’s Za’atari refugee camp near the Syrian border as an example. Her elegant solution to the infrastructural problems these under-resourced and overpopulated communities experience? “Include urban planners in the early phases of the humanitarian emergency to design out future infrastructure problems,” as if the political question of resources is merely secondary to technical questions of design and expertise (de la Chaux and Haugh 2014, 19; de la Chaux 2015).

In these examples, we can see once again how the ideal type of the “innovator” or entrepreneur emerges as the protagonist of the historical and economic drama unfolding in the peripheral spaces of the world economy. The humanitarian innovator is a flexible, versatile, pliant, and autonomous individual, whose potential is realized in the struggle for wealth accumulation, but whose private zeal for accumulation is thought to benefit society as a whole.[8] Humanitarian or social innovation discourse emphasizes the agency and creativity of “the poor,” by discursively centering the authority of the “user” or entrepreneur rather than the agency or the consumer. Individual qualities like purpose, passion, creativity, and serendipity are mobilized in the service of broad social goals. Yet while this sort of individualism is central in the literature of social and humanitarian innovation, it is not itself a radically new “innovation.” It instead recalls a pattern that Molly Geidel has recently traced in the literature and philosophy of the Peace Corps. In Peace Corps memoirs and in the agency’s own literature, she writes, the “romantic desire” for salvation and identification with the excluded “poor” was channeled into the “technocratic language of development” (2015, 64).

Innovation’s emphasis on the intellectual, spiritual, and creative faculties of single entrepreneur as historically decisive recapitulates in these especially individualistic terms a persistent thread in Cold War development thinking: its emphasis on cultural transformations as prerequisites for economic ones. At the same time, humanitarian innovation’s anti-bureaucratic ethos of autonomy and creativity is often framed as a critique of “developmentalism” as a practice and an industry. It is a response to criticisms of twentieth-century development as a form of neocolonialism, as too growth-dependent, too detached from local needs, too fixated on big projects, too hierarchical. Consider the development agency UNICEF, whose 2014 “Innovation Annual Report” embraces a vocabulary and funding model borrowed from venture capital. “We knew that we needed to help solve concrete problems experienced by real people,” reads the report, “not just building imagined solutions at our New York headquarters and then deploy them” (UNICEF 2014, 2). Rejecting a hierarchical model of modernization, in which an American developmentalist elite “deploys” its models elsewhere, UNICEF proposes “empowerment” from within. And in place of “development,” as a technical process of improvement from a belated historical and economic position of premodernity, there is “innovation,” the creative capacity responsive to the desires and talents of the underdeveloped.

As in the social innovation model promoted by the Stanford Business School and the ideal of “empowerment” advanced by Grameen, the literature of humanitarian innovation sees “the market” as a neutral field. The conflict between the private sector, military, other non-humanitarian actors in the process of humanitarian innovation is mitigated by considering each as an equivalent “stakeholder,” with a shared “investment” in the enterprise and its success; abuse of the humanitarian mission by profit-seeking and military “stakeholders” can be prevented via the fabrication of “best practices” and “voluntary codes of conduct” (Betts and Bloom 2015, 24) One report, produced for ALNAP along with the Humanitarian Innovation Fund, draws on Everett Rogers’s canonical theory of innovation diffusion. Rogers taxonomizes and explains the ways innovative products or methods circulate, from the most forward-thinking “early adopters” to the “laggards” (1983, 247-250). The ALNAP report does grapple with the problems of importing profit-seeking models into humanitarian work, however. “In general,” write Obrecht and Warner (2014, 80-81), “it is important to bear in mind that the objective for humanitarian scaling is improvement to humanitarian assistance, not profit.” Here, the problem is explained as one of “diffusion” and institutional biases in non-profit organizations, not a conflict of interest or a failing of the private market. In the humanitarian sector, they write, “early adopters” of innovations developed elsewhere are comparatively rare, since non-profit workers tend to be biased towards techniques and products they develop themselves. However, as Wendy Brown (2015, 129) has recently argued about the concepts of “best practices” and “benchmarking,” the problem is not necessarily that the goals being set or practices being emulated are intrinsically bad. The problem lies in “the separation of practices from products,” or in other words, the notion that organizational practices translate seamlessly across business, political, and knowledge enterprises, and that different products—market dominance, massive profits, reliable electricity in a rural hamlet, basic literacy—can be accomplished via practices imported from the business world.

Again, my objective here is not to evaluate the success of individual initiatives pursued under this rubric, nor to castigate individual humanitarian aid projects as irredeemably “neoliberal” and therefore beyond the pale. To do so basks a bit too easily in the comfort of condemnation that the pejorative “neoliberal” offers the social critic, and it runs the risk, as Ferguson (2009, 169) writes, of nostalgia for the era of “old-style developmental states,” which were mostly capitalist as well, after all.[9] Instead, my point is to emphasize the political work that “innovation” as a concept does: it depoliticizes the resource scarcity that makes it seem necessary in the first place by treating the private market as a neutral arbiter or helpful partner rather than an exploiter, and it does so by disavowing the power of a Western subject through the supposed humility and democratic patina of its rhetoric. For example, the USAID Development Innovation Ventures, which seeds projects that will win support from private lenders later, stipulates that “applicants must explain how they will use DIV funds in a catalytic fashion so that they can raise needed resources from sources other than DIV” (USAID 2017). The hoped-for innovation here, it would seem, is the skill with which the applicants accommodate the scarcity of resources, and the facility with which they commercialize their project. One funded project, an initiative to encourage bicycle helmets in Cambodia, “has the potential to save the Cambodian government millions of dollars over the next 10 years,” the description proclaims. But obviously, just because something saves the Cambodian government millions doesn’t mean there is a net gain for the health and safety of Cambodians. It could simply allow the Cambodian government to give more money away to private industry or buy $10 million worth of new weapons to police the Laotian border. “Innovation,” here, requires an adjustment to austerity.

Adjustment, often reframed positively as “resilience,” is a key concept in this literature. In another report, Betts, Bloom, and Weaver (2015, 8) single out a few exemplary innovators from the informal economy of the displaced person’s camp. They include tailors in a Syrian camp’s outdoor market; the Somali owner of an internet café in a Kenyan refugee camp; an Ethiopian man who repairs refrigerators with salvaged air conditioners and fans; and a Ugandan who built a video-game arcade in a settlement near the Rwandan border. This man, identified only as Abdi, has amassed a collection of second-hand televisions and game consoles he acquired in Kampala, the Ugandan capital. “Instead of waiting for donors I wanted to make a living,” says Abdi in the report, exemplifying the values of what Betts, Bloom, and Weaver call “bottom-up innovation” by the refugee entrepreneur. Their assessment is a generous one that embraces the ingenuity and knowledge of displaced and impoverished people affected by crisis. Top-down or “sector-wide” development aid, they write, “disregards the capabilities and adaptive resourcefulness that people and communities affected by conflict and disaster often demonstrate” (2015, 2). In this report, refugees are people of “great resilience,” whose “creativity” makes them “change makers.” As Julian Reid and Brad Evans write, we apply the word “resilient” to a population “insofar as it adapts to rather than resists the conditions of its suffering in the world” (2014, 81). The discourse of humanitarian innovation has the same concession to the inevitability of the structural conditions that make such resilience necessary in the first place. Nowhere is it suggested that refugee capitalists might be other than benevolent, or that inclusion in circuits of national and transnational capital might exacerbate existing inequalities, rather than transcend them. Furthermore, humanitarian innovation advocates never argue that market-based product and service “innovation” are, in a refugee context, beneficial to the whole, given the paucity of employment and services in affected communities; this would at least be an arguable point. The problem is that the question is never even asked. The market is like oxygen.

Conclusion: The TED Talk and the Innovation Romance

In 2003, I visited a recently-settled barrio settlement—one could call it a “shantytown”—perched on a hillside high above the east side of Caracas. I remember vividly a wooden, handmade press, ringed with barbed wire scavenged from a nearby business, that its owner, a middle-aged woman newly arrived in the capital, used to crush sugar cane into juice. It was certainly an innovation, by any reasonable definition: a novel, creative solution to a problem of scarcity, a new process for doing something. I remember being deeply impressed by the device, which I found brilliantly ingenious. What I never thought to call it, though, was a “solution” to its owner’s poverty. Nor, I am sure, did she; she lived in a hard-core chavista neighborhood, where dispossessing the country’s “oligarchs” would have been offered as a better innovation—in the old Emma Goldman sense. Therefore, it is not that individual ingenuity, creativity, fearlessness, hard work, and resistance to the impossible demands that transnational capital has placed on people like the video-game entrepreneur in Uganda, or that woman in Caracas, are disreputable things to single out and praise. Quite the contrary: my objection is to the capitulation to their exploitation that is smuggled in with this admiration.

I have argued that “innovation” is, at best, a vague concept asked to accommodate far too much in its combination of heroic and technocratic meanings. Innovation, in its modern meaning, is about revolutionizing “process” and technique: this often leaves outcomes unexamined and unquestioned. The outcome of that innovative sugar cane press in Caracas is still a meager income selling juice in a perilous informal marketplace. The promiscuity of innovation’s use also makes it highly mobile and subject to abuse, as even enthusiastic users of the concept, like Betts and Bloom at the Oxford Humanitarian Innovation Project, acknowledge. As they caution, “use of the term in the humanitarian system has lacked conceptual clarity, leading to misuse, overuse, and the risk that it may become hollow rhetoric” (2014, 5). I have also argued that innovation, especially in the context of neoliberal development, must be understood in moral terms, as it makes a virtue of private accumulation and accomodation to scarcity, and it circulates an ego-ideal of the first-world self to an audience of its admirers. It is also an ideological celebration of what Harvey calls the neoliberal alignment of individual well-being with unregulated markets, and what Brown calls “the economization of the self” (2015, 33). Finally, as a response to the enduring crises of third-world poverty, exacerbated by the economic and ecological dangers of the twenty-first century, the language of innovation beats a pessimistic retreat from the ideal of global equality that, in theory at least, development in its manifold forms always held out as its horizon.

Innovation discourse draws on deep wells—its moral claim is not new, as a reader of The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism will observe. Inspired in part by the example of Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography, Max Weber argued that capitalism in its ascendancy reimagined profit-seeking activities, which might once have been described as avaricious or vulgar as a virtuous “ethos” (2001, 16-17). Capitalism’s challenge to tradition, Weber argued, demanded some justification; reframing business as a calling or a vocation could help provide one. Capitalism in our time demands still demands validation not only as a virtuous discipline, but as an enterprise devoted to serving the “common good,” write Boltanski and Chiapello. As they say, “an existence attuned to the requirements of accumulation must be marked out for a large number of actors to deem it worth the effort of being lived” (2007, 10-11). “Innovation” as an ideology marks out this sphere of purposeful living for the contemporary managerial classes. Here, again, the word’s close association with “creativity” is instrumental, since creativity is often thought to be an intrinsic, instinctual human behavior. “Innovating” is therefore not only a business practice that will, as Franklin argued about his own industriousness, improve oneself in the eyes of both man and God. It is also a secular expression of the most fundamental individual and social features of the self—the impulse to understand and to improve the world. This is particularly evident in the discourse of social innovation, which the Social Innovation Lab at Stanford defines as a practice that aims to leverage the private market to solve modern society’s most intractable “problems”: housing, pollution, hunger, education, and so on. When something like world hunger is described as a “problem” in this way, though, international food systems, agribusiness, international trade, land ownership, and other sources of malnutrition disappear. Structures of oppression and inequality simply become discrete “problems” for no one has yet invented the fix. They are individual nails in search of a hammer, and the social innovator is quite confident that a hammer exists for hunger.

Microfinance is another one of these hammers. As one economist critical of the microcredit system notes at the beginning of his own book on the subject, “most accounts of microfinance—the large-scale, businesslike provision of financial services to poor people—begin with a story” (Roodman 2012, 1). These are usually some narrative of an encounter with a sympathetic third-world subject. For Roodman, the microfinancial stories of hardship and transcendence have a seductive power over their first-world audiences, of which he is legitimately suspicious. As we saw above, Schumpeter’s procedural “entrepreneurial function” is itself also a story of a creative entrepreneur navigating the tempests of modern capitalism. In the postmodern romance of social innovation in the “underdeveloped” world, the Western subject of the drama is both ever-present and constantly disavowed. The TED Talk, with which we began, is in its crude way the most expressive genre of this contemporary version of the entrepreneurial romance.

Rhetorically transformative but formally archaic—what could be less innovative than a lecture?—the genre of the social innovation TED Talk models innovation ideology’s combination of grandiosity and proceduralism, even as its strict generic conventions—so often and easily parodied—repeatedly undermine the speakers’ regular claims to transcendent breakthroughs. For example, in his TEDx Montreal address, Ethan Kay (2012) began in the conventional way: with a dire assessment of a monumental, yet easily overlooked, social problem in a third-world country. “If we were to think about the biggest problems affecting our world,” Kay begins, “any socially conscious person would have to include poverty, disease, and climate change. And yet there is one thing that causes all three of these simultaneously, that we pay almost no attention to, even though a very good solution exists.” Having established the scope of the problem, next comes the sentimental identification. The knowledge of this social problem is only possible because of the hospitality and insight of some poor person abroad, something familiar from Geidel’s reading of Peace Corps memoirs and Roodman’s microcredit stories: in Kay’s case, it is in the unelectrified “hut” of a rural Indian woman where, choking on cooking smoke, he realizes the need for a clean-burning indoor cookstove. Then comes the self-deprecating joke, in which the speaker acknowledges his early naivete and establishes his humble capacity for self-reflection. (“I’m just a guy from Cleveland, Ohio, who has trouble cooking a grilled-cheese sandwich,” says Kay, winning a few reluctant laughs.) And then, the technocratic solution emerges: when the insight thus acquired is subjected to the speaker’s reason and empathy, the deceptively simple and yet world-making “solution” emerges. Despite the prominent formal place of the underdeveloped character in this genre, the teller of the innovation story inevitably ends up the hero. The throat-clearing self-seriousness, the ritualistic gestures of humility, the promise to the audience of transformative change without inconvenient political consequences, and the faith in technology as a social leveler all perform the TED Talk’s ego-ideal of social “innovation.”

One of the most successful social innovation TED Talks is Mitra’s tale of the “self-organized learning environment” (SOLE). Mitra won a $1 million prize from TED in 2013 for a talk based on his “hole-in-the-wall” experiment in New Delhi, which tests poor children’s ability to learn autonomously, guided only by internet-enabled laptops and cloud-based adult mentors abroad. (Ted.com 2013). Mitra’s idea was an excellent example of innovation discourse’s combination of the procedural and the prophetic. In the case of the latter, he begins: “There was a time when Stone Age men and women used to sit and look up at the sky and say, ‘What are those twinkling lights?’ They built the first curriculum, but we’ve lost sight of those wondrous questions” (Mitra 2013). What gets us to this lofty goal, however, is a comparatively simple process. True to genre, Mitra describes the SOLE as the fruit of a serendipitous discovery. After cutting a hole in the wall that separated his technology firm’s offices from an adjoining New Delhi slum, they placed an Internet-enabled computer in the new common area. When he returned weeks later, Mitra found local children using it expertly. Leaving unsupervised children in a room with a laptop, it turns out, activates innate capacities for self-directed learning stifled by conventional schooling. Mitra promises a cost-effective solution to the problem of primary and secondary education in the developing world—do virtually nothing. “This is done by children without the help of any teacher,” Mitra confidently concludes, sharing a PowerPoint slide of the students’ work. “The teacher only raises the question, and then stands back and admires the answer.”

When we consider innovation’s religious origins in false prophecy, its current orthodoxy in the discourse of technological evangelism—and, more broadly, in analog versions of social innovation—is often a nearly literal example of Rayvon Fouché’s argument that the formerly colonized, “once attended to by bibles and missionaries, now receive the proselytizing efforts of computer scientists wielding integrated circuits in the digital age” (2012, 62). One of the additional ironies of contemporary innovation ideology, though, is that these populations exploited by global capitalism are increasingly charged with redeeming it—the comfortable denizens of the West need only “stand back and admire” the process driven by the entrepreneurial labor of the newly digital underdeveloped subject. To the pain of unemployment, the selfishness of material pursuits, the exploitation of most of humanity by a fraction, the specter of environmental cataclysm that stalks our future and haunts our imagination, and the scandal of illiteracy, market-driven innovation projects like Mitra’s “hole in the wall” offer next to nothing, while claiming to offer almost everything.

_____

John Patrick Leary is associate professor of English at Wayne State University in Detroit and a visiting scholar in the Program in Literary Theory at the Universidade de Lisboa in Portugal in 2019. He is the author of A Cultural History of Underdevelopment: Latin America in the U.S. Imagination (Virginia 2016) and Keywords: The New Language of Capitalism, forthcoming in 2019 from Haymarket Books. He blogs about the language and culture of contemporary capitalism at theageofausterity.

_____

Notes

[1] “The entrepreneur and his function are not difficult to conceptualize,” Schumpeter writes: “the defining characteristic is simply the doing of new things or the doing of things that are already being done in a new way (innovation).”

[2] The term “underdeveloped” was only a bit older: it first appeared in “The Economic Advancement of Under-developed Areas,” a 1942 pamphlet on colonial economic planning by a British economist, Wilfrid Benson.

[3] I explore this semantic and intellectual history in more detail in my book, A Cultural History of Underdevelopment (Leary, 4-10).

[4] Morozov describes solutionism as an ideology that sanctions the following delusion: “Recasting all complex social situations either as neatly defined problems with definite, computable solutions or as transparent and self-evident processes that can be easily optimized—if only the right algorithms are in place!”

[5] “Although the number of unbanked people globally dropped by half a billion from 2011 to 2014,” reads a Foundation web site’s entry under the tab “financial services”, “two billion people are still locked out of formal financial services.” One solution to this problem focuses on Filipino convenience stores, called “sari-sari” stores: “In a project funded by the JPMorgan Chase Foundation, Grameen Foundation is empowering sari-sari store operators to serve as digital financial service agents to their customers.” Clearly, the project must result not only in connecting customers to financial services, but in opening up new markets to JP Morgan Chase. See “Alternative Channels.”

[6] This quoted definition of “humanitarian innovation” is attributed to an interview with an unnamed international aid worker.

[7] Erickson (2015, 113-14) writes that “design thinking” in public education “offers the illusion that structural and institutional problems can be solved through a series of cognitive actions…” She calls it “magic, the only alchemy that matters.”

[8] A management-studies article on the growth of so-called “innovation prizes” for global development claimed sunnily that at a recent conference devoted to such incentives, “there was a sense that society is on the brink of something new, something big, and something that has the power to change the world for the better” (Everett, Wagner, and Barnett 2012, 108).

[9] “It is here that we have to look more carefully at the ‘arts of government’ that have so radically reconfigured the world in the last few decades,” writes Ferguson, “and I think we have to come up with something more interesting to say about them than just that we’re against them.” Ferguson points out that neoliberalism in Africa—the violent disruption of national markets by imperial capital—looks much different than it does in western Europe, where it usually treated as a form of political rationality or an “art of government” modeled on markets. It is the political rationality, as it is formed through an encounter with the “third world” object of imperial neoliberal capital, that is my concern here.

_____

Works Cited

- Bacon, Francis. 1844. The Works of Francis Bacon, Lord Chancellor of England. Vol. 1. London: Carey and Hart.

- Banerjee, Abhijit, et al. 2015. “The Miracle of Microfinance? Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7:1.

- Betts, Alexander, Louise Bloom, and Nina Weaver. 2015. “Refugee Innovation: Humanitarian Innovation That Starts with Communities.” Humanitarian Innovation Project, University of Oxford.

- Betts, Alexander and Louise Bloom. 2014. “Humanitarian Innovation: The State of the Art.” OCHA Policy and Studies Series.

- Boltanski, Luc and Eve Chiapello. 2007. The New Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Gregory Elliot. New York: Verso.

- Brown, Tim and Jocelyn Wyatt. 2010. “Design Thinking for Social Innovation.” Stanford Social Innovation Review.

- Brown, Wendy. 2015. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. New York: Zone Books.

- Burke, Edmund. 1798. The Beauties of the Late Right Hon. Edmund Burke, Selected from the Writings, &c., of that Extraordinary Man. London: J.W. Myers.

- Calvin, John. 1763. The Institution of the Christian Religion. Translated by Thomas Norton. Glasgow: John Bryce and Archibald McLean.

- Clark, Donald. 2013. “Sugata Mitra: Slum Chic? 7 Reasons for Doubt.”

- Cowen, M.P. and R.W. Shenton. 1996. Doctrines of Development. London: Routledge.

- De la Chaux, Marlen, 2015. “Rethinking Refugee Camps: Turning Boredom into Innovation.” The Conversation (Sep 24).

- De la Chaux, Marlen and Helen Haugh. 2014. “Entrepreneurship and Innovation: How Institutional Voids Shape Economic Opportunities in Refugee Camps.” Judge Business School, University of Cambridge,

- Erickson, Megan. 2015. Class War: The Privatization of Childhood. New York: Verso.

- Everett, Bryony, Erika Wagner, and Christopher Barnett. 2012. “Using Innovation Prizes to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals.” Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 7:1.

- Ferguson, James. 2009. “The Uses of Neoliberalism.” Antipode 41:S1.

- Fouché, Rayvon. 2012. “From Black Inventors to One Laptop Per Child: Exporting a Racial Politics of Technology.” In Race after the Internet, edited by Lisa Nakamura and Peter Chow-White. New York: Routledge. 61-84

- Frank, Andre Gunder. 1991. The Development of Underdevelopment. Stockholm, Sweden: Bethany Books.

- Geidel, Molly. 2015. Peace Corps Fantasies: How Development Shaped the Global Sixties. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gilman, Nils. 2003. Mandarins of the Future: Modernization Theory in Cold War America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

- Godin, Benoit. 2015. Innovation Contested: The Idea of Innovation Over the Centuries. New York: Routledge.

- Goldman, Emma. 2000. “Anarchism: What It Really Stands For.” Marxists Internet Archive.

- Grameen Foundation India. No date. “Our History.”

- Hobbes, Thomas. 1949. De Cive, or The Citizen. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Institute of Leadership and Management. 2007. Managing Creativity and Innovation in the Workplace. Oxford, UK: Elsevier.

- Johnson, Steven. 2011. The Innovator’s Cookbook: Essentials for Inventing What is Next. New York: Riverhead.

- Kay, Ethan. 2012. “Saving Lives Through Clean Cookstoves.” TEDx Montreal.

- Kelley, Tom. 2001. The Art of Innovation: Lessons in Creativity from IDEO, America’s Leading Design Firm. New York: Crown Business.

- Larrain, Jorge. 1991. Theories of Development: Capitalism, Colonialism and Dependency. New York: Wiley.

- Leary, John Patrick. 2016. A Cultural History of Underdevelopment: Latin America in the U.S. Imagination. University of Virginia Press.

- Lepore, Jill. 2014. “The Disruption Machine: What the Gospel of Innovation Gets Wrong.” The New Yorker (Jun 23).

- Marshall, Marguerite Moore. 1914. “In Dancing the Denatured Tango the Couple Keep Two Feet Apart.” The Evening World (Jan 24).

- Mitra, Sugata. 2013. “Build a School in the Cloud.”

- Morozov, Evgeny. 2014. To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism. New York: Public Affairs.

- Moss, Frank. 2011. The Sorcerers and Their Apprentices: How the Digital Magicians of the MIT Media Lab Are Creating the Innovative Technologies that Will Transform Our Lives. New York: Crown Business.

- National Economic Council and Office of Science and Technology Policy. 2015. “A Strategy for American Innovation.” Washington, DC: The White House.

- North, Michael. 2013. Novelty: A History of the New. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Nustad, Knut G. 2007. “Development: The Devil We Know?” In Exploring Post-Development: Theory and Practice, Problems and Perspectives, edited by Aram Ziai. London: Routledge. 35-46.

- Obrecht Alice and Alexandra T. Warner. 2014. “More than Just Luck: Innovation in Humanitarian Action.” London: ALNAP/ODI.

- O’Connor, Kevin and Paul B. Brown. 2003. The Map of Innovation: Creating Something Out of Nothing. New York: Crown.

- Peters, Tom. 1999. The Circle of Innovation: You Can’t Shrink Your Way to Greatness. New York: Vintage.

- Polgreen, Lydia and Vikas Bajaj. 2010. “India Microcredit Faces Collapse From Defaults.” The New York Times (Nov 17).

- Rodney, Walter. 1981. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Washington, DC: Howard University Press.

- Ross, Kristin. 1996. Fast Cars, Clean Bodies: Decolonization and the Reordering of French Culture. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Rostow, Walter. 1965. The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Reid, Julian and Brad Evans. 2014. Resilient Life: The Art of Living Dangerously. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Rogers, Everett M. 1983. Diffusion of Innovations. Third edition. New York: The Free Press.

- Roodman, David. 2012. Due Diligence: An Impertinent Inquiry into Microfinance. Washington, D.C.: Center for Global Development.

- Saldaña-Portillo, Josefina. 2003. The Revolutionary Imagination in the Americas and the Age of Development. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Schumpeter, Joseph. 1934. The Theory of Economic Development. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press.

- Schumpeter, Joseph. 1941. “The Creative Response in Economic History,” The Journal of Economic History 7:2.

- Schumpeter, Joseph. 2003. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. London: Routledge.

- Seitler, Ellen. 2005. The Internet Playground: Children’s Access, Entertainment, and Miseducation. New York: Peter Lang.

- Shakespeare, William. 2005. Henry IV. New York: Bantam Classics.

- Smithers, Rebecca. 2015. “University Intalls Prototype ‘Pee Power’ Toilet.” The Guardian (Mar 5).

- Stanford Graduate School of Business, Center for Social Innovation. No date. “Defining Social Innovation.”

- Sweezy, Paul. 1943. “Professor Schumpeter’s Theory of Innovation.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 25:1.

- TED.com. No date. “Our Organization.”

- TED.com. 2013. “Sugata Mitra Creates a School in the Cloud.”

- Truman, Harry. 1949. “Inaugural Address, January 20, 1949.”

- UNICEF. 2014. “UNICEF Innovation Annual Report 2014: Focus on Future Strategy.”

- USAID. 2017. “DIV’s Model in Detail.” (Apr 3).

- Weber, Max. 2001. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Talcott Parsons. London: Routledge Classics.

- Yunus, Muhammad. 2012. “A History of Microfinance.” TEDx Vienna.

Leave a Reply