by Brian Willems

This is not an essay which aims at creating knowledge. It will not provide a new interpretation of a text. Nor will it apply a new critical perspective in order to uncover unseen aspects of a work.

Instead of being part of what Joseph North calls the “historicist/contextualist” paradigm, limiting itself to self-referential scholarly study, this work aims to be a piece of criticism, in the outdated I.A. Richards’ sense of the term. This means the essay, and the experiment it describes, attempt to have real-world effects and consequences. It does so through an experiment called Natural Instruments.

Natural Instruments are experimental financial algorithms founded on natural processes. However, they are not a part of what Anthony Brabazon and Michael O’Neill have collated under the idea of Biologically Inspired Algorithms for Financial Trading, which takes models of social interaction, immune systems and the function of biological neurons as its inspiration. The aim of Natural Instruments is not to make money, but to highlight some of the problems found in financial trading of the past and present, and to attempt to find new ways to imagine a future outside the financial time of hedged potentialities and long-term debt obligation. One way of doing this is to connect financial trading instruments with non-human aspects of the world. Thus Natural Instruments are trading algorithms under the direct control of nature.

While the connection between nature and automated trading may sound like something new, they are actually intimately and historically linked. The basis of the theory of automated financial trading goes back to the random motion of pollen grains suspended in water, first observed by British botanist Robert Brown in 1827. The motion of the pollen grains, eventually called Brownian Motion, became the “random walk” of the “efficient market hypothesis,” the blindness of which help lead to the 2007-8 financial crisis. Natural Instruments are experiments which illustrate the problem of the efficient market hypothesis. They live on extreme volatility rather than trying to contain it. They do this by repeating Brown’s experiment, in a way. In the first of a series of such experiments, a pollen grain is given direct control over financial trading.

One key feature of fictional financial algorithms is that they foreground the volatility of the data an algorithm is based on. Some novelists, such as Kim Stanley Robinson and Hari Kunzru, have created fictional financial instruments which reflect rather than contain this volatility.

In the financial world, volatility is defined by the standard deviation of a set of data. Standard deviation is the spread of data around its mean, with a standard deviation of 3 mostly seen as an acceptable margin of error in statistics. Therefore, the higher the deviation, the more volatility there is. The role of volatility in financial algorithms is important because it defines the kind of world the algorithm can take into account. Here I am following the work of Peli Grietzer, who recently defended his PhD Ambient Meaning. Grietzer connects the function of autoencoder algorithms to literary theory. What is key for our discussion is that “When we extend the concepts of a canon, worldview, and mimesis to the world of algorithms, we detach the canon/worldview/mimesis triplet from its natural domain of art and culture to identify it with any and all structural triangles that comprise a set of privileged objects (canon), a schema of interpretation (worldview), and a capacity for reproduction and representation (mimesis).” Hence, just as a literary critic unfamiliar with feminism has problems asking certain important questions about a text, when an event lies outside an algorithm’s assumed standard deviation, the algorithm cannot “see” what happened. Such models, in the words of Brian Holmes, are “the source of a fundamental disconnect between the informational sky above our heads and the existential ground beneath our feet.”

For example, as Scott Patterson shows in Dark Pools, an influential paper from the mid-90s argued that the 1987 stock market crash was a theoretically impossible “27-standard deviation event,” meaning that “Even if one were to have lived through the entire 20 billion year life of the universe and experienced this 20 billion times (20 billion big bangs), that such a decline could have happened even once in this period is a virtual impossibility.” In general, the algorithms used before the Black Monday crash of 1987 were not programmed to include the kind of volatility that was taking place in the real world. Instead, they assumed the world was a much more stable place. Some financial algorithms found in contemporary fiction have addressed this problem directly by placing extreme volatility at the heart of how the algorithms work.

As mentioned earlier, the problems some real-world financial algorithms have with extreme volatility are due to two main factors: the idea of a random walk and the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH). Put simply, the random walk means that on a micro scale, past performance of a stock price has no bearing on future performance. For example, if a stock price moves down, this has no relation as to whether the next move will be up or down. Stock prices go on a “random walk,” meaning that their future state cannot be predicted from their previous state. This observation is based on what Robert Brown saw with pollen grains, which when suspended in water moved in an erratic fashion. Regarding the second factor, at times EMH is confused with the random walk, but it is really quite different. EMH states that the price of a stock reflects all known information about that that stock, thus negating any advantage having knowledge in advance of others might bestow. Its similarity to the random walk is that if prices are efficient, there is no gain to be made on short-term bets.

EMH and the random walk have been popularly combined in Burton Malkiel’s A Random Walk Down Wall Street, which was first published in 1973 and went through 11 revised editions by 2015. Riding out a number of crises and bubbles over the years, Malkiel’s book has never changed its basic investment strategy: the long-term return of the totality of a stock market index (S&P 500, Nasdaq, or a mix of US and non-US indices) will out-perform any short-term investment strategy in individual stocks. Believing that future stock price changes cannot be predicted (the random walk) and that all pertinent information about an asset will be shared (EMH), Malkiel suggests investing in a Total Stock Market Index, meaning buying every single stock of an index and holding on to it for as long as possible. This strategy ignores daily volatility and hot picks, instead counting on what are hopefully the gradual, long-term gains of the world economy. By eliminating volatility from his strategy, Malkiel hopes to beat the market over the long term.

The random walk and efficient market theory are key factors in the most well-known financial algorithms, the Black-Scholes-Merton options model. In An Engine, Not a Camera, Donald MacKenzie argues that the wide-spread use of the Black-Scholes-Merton model for financial options was one of the main reasons for the US stock market crash of October 1987. The model brought the market in line with a certain view of volatility. The model is thus “performative,” meaning that it does not just describe the market, but effects it. The Black-Scholes-Merton model assumes a fixed level of volatility for financial assets. When a trader uses the model, and sees a stock deviate from what the model says the correct level of volatility should be, this difference can be exploited for financial gain.

However, the model became performative because when it started to be extremely popular, traders brought the market more in line with the model. “Reality adapted to the theory,” as Elena Esposito says in The Future of Futures. The fixed level of volatility assumed by the Black-Scholes-Merton model is based on the random walk, and the model itself, as Holmes says, “can be placed at the origins of the ‘artificial world model’ of finance capitalism.” Although the random walk assumes random changes from one price point to another (it cannot be predicted whether the price will go up or down), this change in constrained by a simple natural log calculation.

The role of the natural log and its relation to volatility defined by standard deviation is the key intervention that Natural Instruments make in financial models, so let’s take a look at the role of volatility in the Black-Scholes-Merton algorithm, because this is where the output of the Natural Instruments experiment will go.

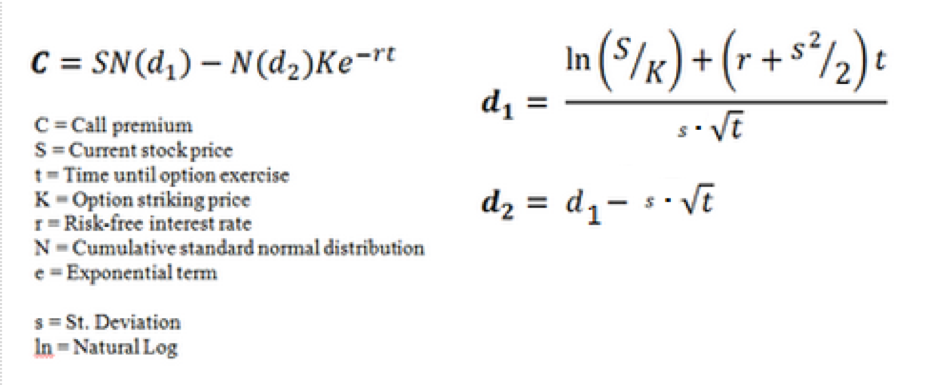

The Black-Scholes-Merton is an algorithm for European-style call options, meaning a contract which allows (but does not oblige) the holder to buy a stock on one specific date for a specific price. It looks like this:

We don’t need to understand everything about the algorithm, but we do need to understand enough in order to understand how the Natural Instruments experiment will work.

Put simply, C is the amount you must pay the option writer, N is a normal bell curve distribution of values, K is the price for which the option could be sold. More interesting for the experiment are e and s. E is the exponential term used in a natural log calculation. Its value is approximately 2.71828, a number which is found when the growth rate of different entities is measured. Populations, the GDP, bank interest, Moore’s law and radioactive decay are all examples of growth which follow e. We want to leave this number alone in the algorithm, since it will come into direct conflict with our target s, or standard deviation. We want to change s in the experiment because this is what the quote above said was impossible when it reached 27. We will see why below.

One piece of fiction that explicitly deals with the fixed volatility of the Black-Scholes-Merton options model is Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140 (2017). The novel features two financial algorithms, although only one will concern us here. The novel is the original inspiration for Natural Instruments.

In the book, rising sea levels caused by climate change have flooded many coastal cities, including New York. However, many of the cities survive, developing new patterns of work and finance based around a water economy.

Franklin Garr, a hedge fund manager, directly addresses the inability of previous financial models to capture the complexity of the current situation, saying near the beginning of the novel: “I was looking at the little waves lapping in the big doors and wondering if the Black-Scholes formula could frame their volatility.” Garr is expressing doubt as to whether this financial model is complex enough to be able to “see” the level of volatility found in the quick-changing situation of the flooded city.

Yet in “A Formal Deduction of the Market,” financial trader and theorist Elie Ayache argues that the formalism of the Black-Scholes-Merton model, meaning the range of volatility it employs, does not just limit its ability to “see” the market, but that it actually creates the market it can take into account. In other words, the model writes the world it supposedly analyses, rather than relating to the variability of the world: “The formalism in its finest form (i.e. Brownian motion) has produced a new reality – the market – that has nothing to do with statistics or with the idea that outcomes are realized at each trial and generate statistical populations.” As Arne De Boever argues, finance makes the world psychotic, meaning that “the speculative operations of finance make human beings disavow existing reality, sometimes in combination with the substitution of another reality for the existing one.”

However, in Robinson’s novel, the psychosis of financial formalism does not mean that betting on flooded properties is off the market. For this, Garr has invented his own algorithm, the Intertidal Property Pricing Index (IPPI), which combines the housing index with changes in sea level. Garr’s index is based on intertidal law, which goes back to Roman times and is still in effect throughout much of the world. Intertidal land is thus, as is stated in Robinson’s novel, a new kind of commons: “It was neither private property nor government property, and therefore, some legal theorists ventured, it was perhaps some kind of return to the commons.” The IPPI is meant to allow for betting on this most volatile of properties: buildings built on land that cannot be owned. “Were you in debt if you owned an asset stuck on a strand no one can own, or were you rich? Who knew?” The answer from Garr is that “My index knew.”

Unlike the Black-Scholes-Merton model, the IPPI is attempting to index nature. It takes actual movements in sea level as a measure of current volatility. Thus in Robinson’s novel, nature is key. This connection to nature makes Garr wonder if the IPPI will work.

This first Natural Instruments experiment aims to re-insert the volatility of nature into financial trading. It does this by putting a trading algorithm under the direct control of pollen grains. It sets out to illustrate, in a very simple manner, Ayache’s contention that one way to challenge the formal blindness of finance is to realize that “the derivatives market … may really be the consequence of true, mathematical Brownian motion.”

To do so a number of steps need to be undertaken:

- Create a program in which can visually track the movements of a pollen grain and export its x, y coordinates into an Excel file;

- Find the standard deviation (more accurately in this case, the standard distance, because two coordinates are used) between the x, y values of each frame captured;

- Input the result of this standard distance into the s of the Black-Scholes-Merton formula.

First, we will run a program that will track the pollen grain and export the movement data. The program is adapted from a common visual tracking tutorial. The program was simply modified to track the pollen grain and then write its x, y coordinates into a .csv Excel file.

For the next step, the pollen grain movement was taken from a video recorded by a group at Hamilton College who recreated Brown’s original experiment. One pollen grain was isolated in the video and then tracked with the program.

The main point of interest of the experiment is that the standard distance calculated for the x, y coordinates is 26.32 (ni_calc). This is extremely close to the 27-standard deviation event which was quoted above as being impossible. This means that either this pollen grain, which was the first one chosen for the experiment, is impossibly rare, or that the financial traders who wrote the essay were looking at the world the wrong way.

This “wrong way” is looking at the world through the Black-Scholes-Merton options model. We can see this by inserting into it a standard deviation of 27, as observed with the pollen grain. But first we must set up a fairly standard option:

stock price (s) of 100.00

strike price (K) of 110.00

rate of interest (r) of 0.1

time until the option can be exercised (t) of 3 years.

When we put 27 into the standard deviation (s) of the Black-Scholes-Merton, we render it useless. The algorithm can calculate a call premium when s is between 1 and 3, but once it reaches 10, not to mention 27, the call premium of the option matches its stock price, rendering the model ineffective:

s 1 = C of 5.85

s 2 = C of 92.15

s 3 = C of 98.02

s 4 = C of 99.95

s 5 = C of 99.99

s 6 = C of 99.99

s 10 = C of 100.00

s 25 = C of 100.00

s 27 = C of 100.00

This progression is also true when different stock prices and strike prices are used: a standard deviation of 10 and above pretty much equalizes the call premium and the stock price (we can extend the number beyond two decimal places and see some minor differences, but that is not important here).

A number of holes can be quickly poked in this argument, ranging from the way the pollen grain was tracked to the option inputs for the Black-Scholes-Merton algorithm. However, this initial version of the experiment does not have to be that accurate. What is important is that it shows that an algorithm based on the random walk of real-world plant grains becomes worthless, thus functioning as an example of what Matteo Pasquinelli calls “creative sabotage.” Or, just as was indicated in Robinson’s novel, the model does not account for the volatility that is expected, it cannot see the world that it is supposedly based on.

This is not the first time problems with volatility have been found in the Black-Scholes-Merton algorithm. Far from it. And this is not an essay written by a mathematician, nor a financial trader. But what this experiment can show is that financial algorithms miss much of the volatility of nature because of the small amount of volatility they are allowed to “see.” This is shown not through the interpretation of a text, but through experimentation based on properties found in a text. This blindness of financial algorithms can cause problems, not just for financial traders but for those with mortgages and other forms of debt which are wrapped up in these financial instruments, as was seen the large number of people who lost their homes in the 2007-8 financial crisis. Creating algorithms which make algorithms useless is one way to expose this danger to housing, jobs, and debt obligations brought about by such “blindness.” Financial algorithms such as the Black-Scholes-Merton model are supposedly based on the natural process of the random walk. Yet, when they are actually controlled by nature, they become useless. This is the revenge of nature, via the algorithm.

Ayache, Elie. “A Formal Reduction of the Market.” Collapse 8 (2014): 959-998.

Brabazon, Anthony and Michael O’Neill. Biologically Inspired Algorithms for Financial

Trading. Berlin: Springer, 2006.

De Boever, Arne. Finance Fictions: Realism and Psychosis in a Time of Economic Crisis.

New York: Fordham University Press, 2018.

Esposito, Elena. The Future of Futures: The Time of Money in Financing and Society.

Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2011.

Grietzer, Peli. Ambient Meaning: Mood, Vibe, System. 2017. Harvard University. PhD

dissertation.

Holmes, Brian. “Is it Written in the Stars? Global Finance, Precarious Destinies.” Continental

Drift. 2009. Internet: https://brianholmes.wordpress.com/2009/11/06/is-it-written-in-the-stars/.

Mackenzie, Donald. An Engine, Not a Camera: How Financial Models Shape Markets.

Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008.

Malkiel, Burton. A Random Walk Down Wall Street: The Time-Tested Strategy for Successful

Investing. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2015.

North, Joseph. Literary Criticism: A Concise Political History. Cambridge: Harvard

University Press, 2017.

Pasquinelli, Matteo. Animal Spirits: A Bestiary of the Commons. Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2008.

Patterson, Scott. Dark Pools: The Rise of the Machine Traders and the Rigging of the U.S.

Stock Market. New York: Crown Business, 2013.

Robinson, Kim Stanley. New York 2140. London: Orbit, 2017.

_____

Brian Willems is assistant professor of film and video at the University of Split, Croatia. He is most recently the author of Speculative Realism and Science Fiction (2017) and Shooting the Moon (2015).