This essay is part of a dossier on The Maghreb after Orientalism.

The provocation for this dossier is a critical examination of what it might mean that Edward Said neglected, even ignored, the Maghreb in his 1978 masterpiece Orientalism. Or, more productively, given that Said teaches us to understand world “areas” as politically constructed categories, what it might have meant to his argument had he given extended consideration to a region (al-maghrib, French North Africa) that has a particularly complex relationship to colonialism and representation. As I’ll argue below, cinema—both foreign and domestic—has been particularly important to representations of the Maghreb. Moreover, Hollywood film was central to the US encounter with the Arab world at a turning point in political history. So as we cast our eye backward on Said’s work on its 40-year anniversary, I inquire about artistic medium and wonder whether Said’s silence on the Maghreb is related to his silence on cinema. In other words, is there a particular relationship between the Maghreb, Orientalism, and cinema? And what in turn would extended attention to cinema mean to understanding the way Orientalism operated in the US and American cultural production in Orientalism?

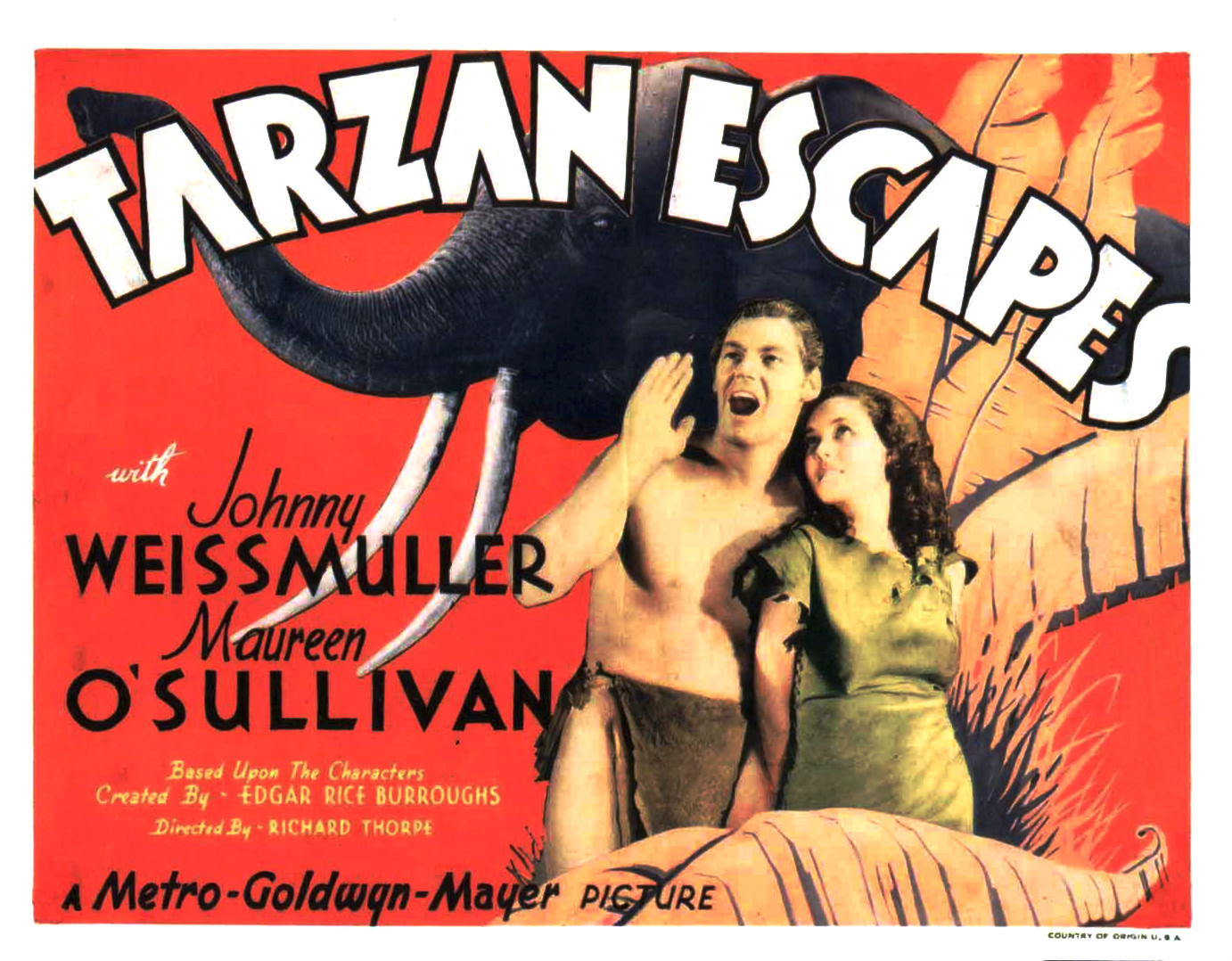

In a piece written for Interview in 1989, Edward Said rhapsodized about Johnny Weissmuller, the swimmer-turned-actor who played Tarzan in a dozen movies during the 1930s and 1940s. In the Hungarian-born, German-American Weissmuller’s interpretation, Said saw a representation of exile that exceeded the literary character created by Edgar Rice Burroughs. “[A]nyone who saw Weissmuller in his prime can associate Tarzan only with his portrayal,” he wrote. “Weissmuller’s apeman was a genuinely mythic figure, a pure Hollywood product” (Said 2000: 328).

Years later, in a 1998 interview with Sut Jhally, Edward Said made another notable reference to Hollywood, describing the joy with which he watched movies as a child:

Growing up in the Middle East . . . [I] used to delight in films on the Arabian Nights, you know done by Hollywood producers . . . with Jon Hall and Maria Montez and Sabu. I mean they were talking about [the] part of the world that I lived in but it had this kind of exotic, magical quality which was what we call today Hollywood. So there was that whole repertory of the sheiks in the desert and galloping around and the scimitars and the dancing girls and all of that.[1]

The next year, in his memoir Out of Place, Said elaborated on his youthful fascination with cinema as a source of stories and referred to Saturday afternoons spent at the Cairo cinemahouse. “It was very odd,” Said comments, “but it did not occur to me that the cinematic Aladdin, Ali Baba, and Sinbad, whose genies, Baghdad cronies, and sultans I completely possessed in the fantasies I counterpointed with my lessons, all had American accents, spoke no Arabic, and ate mysterious foods—perhaps ‘sweetmeats,’ or was it more like stew, rice, lamb cutlets?—that I could never quite make out.”[2]

Given Said’s fanboy appreciation of Hollywood colonial fantasies and his interest in the literary representation of the “pleasures of imperialism,” it is perhaps surprising that cinema plays such a minor role in Orientalism or his work in general.[3] Indeed, outside a reference to “Valentino’s Sheik,” a mention of newsreels, and a comment about “caricatures propagated in the popular culture,” cinema is not present in the 1978 masterwork (287, 290). To be sure, in interviews Said would frequently make references to popular culture and media, including television, but feature-length films do not figure in his otherwise capacious analysis.

Rather than take Said to task for yet another lacuna, we should wonder whether his relative silence on cinema in Orientalism is dictated by the historical arc of his argument, a critical distaste for popular culture, or is otherwise meaningful. The historical explanation is compelling enough: Said anchors Orientalism in the late-eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, only at the end of which does cinema begin to emerge. Napoleon’s 1798 invasion of Egypt is a key episode for Said, particularly notable since the French imperial conquest was accompanied by a massive scholarly project. Said’s archive of Orientalism is rich in poetry, fiction, anthropology, scholarship, and painting, and he is clearly more interested in rich, textual discourse than popular ephemera. Gérard de Nerval and Eugène Delacroix are central; Valentino and Sabu are not.

Let us consider when cinema arrives on the scene. Historians of film point to the 1890s as the decade when cinema was invented—the projection of short films by the Lumière Brothers in Paris in 1895 was a signal event. Scholars who have attended to the history of ways of seeing and looking have charted earlier urban forms (the panaroma painting, the shopping arcade) which make the arrival of cinema and its dramatically different manner of representation seem less starkly disruptive (Anne Friedberg 1993; Jonathan Crary 1990). Despite the arrival of this new form, feature-length films, such as the massively popular The Sheik (1921) and Foreign Legion pictures such as Beau Geste (1926; remade famously in 1939, and several times later), were some time off, after the Great War of 1914-18.

Still, given the extent to which Said focuses on twentieth-century US forms of domination in the final, 120-page chapter, it is somewhat surprising that Orientalism pays no attention to the most prevalent and dominant form of cultural production during the so-called “American century.” A decade later, his extended and subtle reading of Weissmuller’s essentially mute portrayal of Tarzan—in sharp distinction to the highly literate character in Burroughs’s novels—demonstrates Said’s sense that cinema is notably and profoundly different as a representational medium. Thus the lack of attention to cinema in Orientalism is both lamentable and provocative, since it suggests that Orientalism may follow different logics when it appears in the seventh art. And given the dominance Hollywood would come to exert globally, and the ways in which American audiences gravitated to visual media (both film and television) for entertainment in the second half of the twentieth century, splicing cinema out would seem to limit our understanding of how the US managed its emerging relationship to the colonial world. That films set in the Maghreb are central to this bibilography (from The Sheik and its sequels, to desert romances such as The Garden of Allah and Morocco and Foreign Legion pictures in the 1920s and 1930s to Casablanca and desert war films during the 1940s and beyond) is not, I’ll argue, incidental.

There are different ways to understand the importance of film to Orientalism. For my purposes I want to outline two distinct, but related, aspects. First, in the early 20th century, cinema takes its place in the chronology of dominant forms of artistic production. And second, cinema has an intimate relationship to the history of empire, and to postcolonial forms of domination. These may be separated. In a famous passage, Said notes: “The period of immense advance in the institutions and content of Orientalism coincides exactly with the period of unparalleled European expansion; from 1815 to 1914 European direct colonial dominion expanded from about 35 percent of the earth’s surface to about 85 percent of it” (1978: 41). During the height of Orientalism, as Said periodizes it, the dominant form of narrative cultural production is the novel, followed by travel literature. Precisely when European imperial power is at its apex, a new challenger arrives, both in geopolitical and cultural terms. Cinema emerges as a new technology and form of entertainment at the height of the colonial project and will itself become the dominant form of narrative cultural production just as the United States is emerging as a hegemonic power. By the time of World War II, when what Said calls American “ascendancy” on the global scene is secured, the Hollywood studio system has been established as a global corporate power. In what ways would Hollywood’s representation of the so-called Orient reflect the particularities of US neo-imperialism? In what ways would cinema help to create the logics of the postcolonial, neoliberal order?

We can create bibliographies to buttress both the chronological and the neo-imperial approaches to film and Orientalism I have outlined above. Ella Shohat and Robert Stam’s Unthinking Eurocentrism (1994) took an extended look at what they called tropes of empire in cinema, including extended examination of mummy films and the theme of archeology as Orientalism. Matthew Bernstein and Gaylyn Studlar (1997), in the introduction to their important collection Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film, argued that Said’s discourse analysis could be extended to film. In her contribution to that same collection, Antonia Lant (1997) noted the fascination with Egypt, mummies, and pharaohs in very early cinema. Such work provides us with an implicit bridge from the late Victorian novels that Said was so effective at analyzing (such as Kipling’s Kim, 1900-1901) to the new medium, and helps us build the case for the chronological approach.

Another group of scholars, emerging from American studies in the wake of Amy Kaplan and Donald Pease’s watershed collection Cultures of United States Imperialism, with its call for attention to particular forms of US American colonialism, help build a different sort of case that focuses more on American political ascendancy. This approach tends to pick up with the post-WWII period. Melani McAlister’s important Epic Encounters: Culture, Media, and US Interests in the Middle East since 1945 (2001) incorporates a brilliant analysis of Biblical epics in the early cold war. McAlister shows how the portrayal of the Holy Land in Cecil B. DeMille’s Ten Commandments (1956) crafted a vision of American supremacy that channeled rising religious sentiments in the US, suturing American power with the contemporary Middle East reimagined in Biblical terms. As the American postwar economy boomed, a Hollywood version of the Orientalist trope of superfluity overlapped with the popular fascination with American “abundance” as source of the nation’s newfound economic and political strength, melding the technicolor representation of the Orient with Hollywood’s prowess (Edwards, 2001). In the 1950s, Hollywood studios harnessed the sumptuousness of the imagined Orient in lush films to attract audiences to cinema houses as the rise of television posed a commercial threat. In this sense, Hollywood Orientalism served a decidedly domestic purpose. In a similar vein, Christina Klein’s Cold War Orientalism: Asia in the Middlebrow Imagination, 1945-1961 (2003) made a case not only for extending Said’s model to Asia and the Pacific, as the US-Soviet confrontation took on a global scale, but into cinema and popular, “middlebrow” culture. Klein’s analysis includes Reader’s Digest, James Michener, and film musicals such as South Pacific and The King and I, which she argued proffered lessons about international integration to a mass public.

But if the early cold war saw a spate of Biblical epics, Arabian Nights musicals, and historical romances as spaces to work out domestic questions, the films that emerged during and/or depicted World War II’s North African campaign have a more complex legacy. Here is where cinema and Hollywood’s Maghreb both enhance and extend Said’s account of Orientalism most directly. After the November 1942 landings on the Moroccan and Algerian coast (known as Operation Torch), mass numbers of American GIs entered the war for the first time. The American public back home were forced to come to terms with new locations on a world map that were both completely foreign and somehow familiar from Hollywood films from previous decades (references to The Sheik and Beau Geste were frequent in the press). Hollywood war films set in the Maghreb and produced and released during the war juxtaposed figurations of the desert and geopolitical ambitions of the United States during the North African Campaign. General George S. Patton himself, who led the Operation Torch landings at Casablanca, expressed his sense that the land he had “taken” by military means in November 1942 would “be worth a million to Hollywood.” He was quickly proven prescient when Warner Brothers released Casablanca three weeks later (Edwards, 2005).

At first blush, the 1942 Warner Brothers film Casablanca would seem to offer evidence for Said’s case that the continuities of Orientalism carry over into the period of American ascendency. “The old Orientalism was broken into many parts; yet all of them still served the traditional Orientalist dogmas” (Said 1978: 284). In this sense, Casablanca is arguably the best example of high American Orientalism because it imagines a handoff from French colonial power to American models of domination (“I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship,” Rick says famously to Louis Renault, the fictional Vichy prefect of police as they stroll off into a foggy studio set). Although Said does not discuss the film, it would seem to lend itself to this sort of analysis, the transfer of power from one empire to another. Indeed, Hollywood and the Maghreb were at the center of how Americans came to understand “the Arab,” and Casablanca itself, as one of the most successful films in Hollywood history, would become a familiar touchstone. And yet we should also see in Casablanca how it figures a shift in the representational mode of Orientalism itself. Even while Casablanca represents the geopolitical transition from French late-colonialism to postcolonial US patronage in its story and characters, the temporal logics of cinema as medium constituted a distinctly American version of Orientalism.

Casablanca is in this regard the ur-text of American Orientalism because it expressed in celluloid the collision of military occupation and cultural representation, not only within the plot of the film, in which an American casino owner moves from disinterested businessman to wartime political commitment, but also by taking place within a temporality particular to cinema. (The song “As Time Goes By” is shorthand for this temporality.) Beyond Rick’s narrative arc, the studio’s sense that representation on film is akin to ownership is key to the emerging US relationship to Europe’s former colonies. Rick’s disjointed sense of what time he occupies in occupied Morocco (“If it’s December 1941 in Casablanca, what time is it in New York?”) and the famous repetition of Sam’s performance of the theme song operate on a logic of what I call global racial time: the assumption that Arabs and Africans in the global South were at a temporal remove from residents of the United States (see Edwards, 2005, chapter 1). This temporality underlies what would emerge as neoliberalism. The canonical Hollywood film set in an occupied Maghreb suggests that cinema does more than merely repeat and extend British and French Orientalism, but that it innovates too.

That Casablanca quickly became a Hollywood blockbuster in large part because of the coincidence of the US military landings at Casablanca in November 1942 and the interest in the region created by the subsequent North African campaign leads to a further aspect of how cinema creates a distinct form of Orientalism. The film, shot on California stage sets, quickly became equated with the city. The distance or difference between Casablanca and Casablanca was quickly obscured by the success of the movie. Four years later, Warner Brothers tried to discourage the Marx Brothers from entitling their final film A Night in Casablanca. Warner Bros. made the spurious claim that they held a copyright on the word Casablanca. (Groucho Marx responded by claiming that he and his siblings therefore controlled the word brothers and went ahead with the project.) But what begins as a strange joke emerges as a neoliberal reality as location shooting expanded substantially in subsequent decades. Morocco itself would stand in for a wide range of Middle Eastern or “Oriental” locations: the ksar of Ait Benhaddou, on the road between Marrakech and Ouarzazate, would provide the backdrops for both Aqaba in Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and the lost Biblical cities of Sodom and Gomorrah (1962); the area outside Ouarzazate stood in for Tibet in Kundun (1997); Marrakech was Cairo and the desert near Erfoud was Egypt’s Valley of the Kings in The Mummy (1999); Casablanca substituted for Tehran and Beirut in Syriana (2005). One “Oriental” location could substitute for the rest by the Hollywood logics of Orientalism. And as neoliberal arrangements emerged to perpetuate the pattern, Atlas Corporation Studios was founded in Ouarzazate in 1983 by a Moroccan entrepreneur and has been partner to a long list of Hollywood productions since then.

With the advent of the digital age, beginning in the 1990s, another epistemic shift would take place, which goes beyond the purview of this essay. YouTube became an important platform in Morocco within which Moroccans themselves could represent life around them, including in some sensational and influential exposés of police corruption (the so-called Sniper of Targuist) and practices of homosexuality (the notorious Larache wedding videos) (see Edwards, 2016). Here the shift in modes toward YouTube suggests a way to understand the neoliberal relationship between Morocco and the US as a new chapter in Orientalism itself. In the 21st century, digital circulation and an interactive relationship of individual users to media allows for a more dynamic relationship to representation. However, new media and the ability of structurally disempowered amateur filmmakers to share their work with large audiences is not simply liberating, despite the claims of so-called “cyber-utopianists.” The global rise of social media as a space for sharing images and film clips dovetails too with virulent strands of nationalism, and the rapidity and range with which digital technology allows messages to circulate has at times exacerbated some of the tendencies latent in Orientalism. During the 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump leveraged traditions of Orientalism in his call for a Muslim ban and in his excoriation of Khizr and Ghazala Khan, the parents of a US soldier killed in Iraq in 2004 who criticized Trump at the Democratic National Convention (see Edwards, 2018). The ways in which Orientalism survives and mutates in the digital age ushers in a new stage, as the technologies and their logics intersect with the geopolitical concerns that are at the center of representations of Arab and Muslim peoples and places. In order to come to an understanding of those present conjunctures, we must see the transitional stage of Hollywood Orientalism for both its own continuities and ruptures with the previous, colonialist mode.

Brian T. Edwards is Professor of English and Dean of the School of Liberal Arts at Tulane University. Prior to moving to Tulane in 2018, he was on the faculty of Northwestern University, where he was the Crown Professor in Middle East Studies and the founding director of the Program in Middle East and North African Studies. He is the author of Morocco Bound: Disorienting America’s Maghreb, from Casablanca to the Marrakech Express (2005), After the American Century: The Ends of US Culture in the Middle East (2016), and co-editor of Globalizing American Studies (2010).

References

Crary, Jonathan. 1990. Techniques of the Observer: on Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Edwards, Brian T. 2001. “Yankee Pashas and Buried Women: Containing Abundance in 1950s Hollywood Orientalism.” Film & History 31, no. 2: 13-24.

—. 2005. Morocco Bound: Disorienting America’s Maghreb, from Casablanca to the Marrakech Express. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

—. 2016. After the American Century: The Ends of US Culture in the Middle East. New York: Columbia University Press.

—. 2018. “Trump from Reality TV to Twitter, or the Selfie-Determination of Nations,” Arizona Quarterly 74, no. 3: 25-45.

Friedberg, Anne. 1993. Window Shopping: Cinema and the Postmodern. University of California Press.

Kaplan, Amy and Donald Pease, eds. 1993. Cultures of United States Imperialism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Klein, Christina. 2003. Cold War Orientalism: Asia in the Middlebrow Imagination, 1945-1961. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Lant, Antonia. 1997. “The Curse of the Pharaoh, or How Cinema Contracted Egyptomania,” in Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film, edited by Studlar and Bernstein, 69-98 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press).

McAlister, Melani. 2001. Epic Encounters: Culture, Media, and US Interests in the Middle East since 1945. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Said, Edward W. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon.

—. (1989) 2000. “Jungle Calling.” In Reflections on Exile, and Other Essays, 327-36. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

—. 1993. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Knopf.

Shohat, Ella and Robert Stam. 1994. Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media. London and New York: Routledge.

Studlar, Gaylyn and Matthew Bernstein. 1997. Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

[1] “Edward Said: On ‘Orientalism,’” dir. Sut Jhally, Northampton, MA: Media Education Foundation, 1998. Transcript available at: http://www.mediaed.org/transcripts/Edward-Said-On-Orientalism-Transcript.pdf

[2] Edward W. Said, Out of Place: A Memoir (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999), 34.

[3] Said’s chapter on Kipling’s Kim in Culture and Imperialism is called “The Pleasures of Imperialism” (Said 1993: 132-62).

Leave a Reply