by Stefano Ercolino

I.

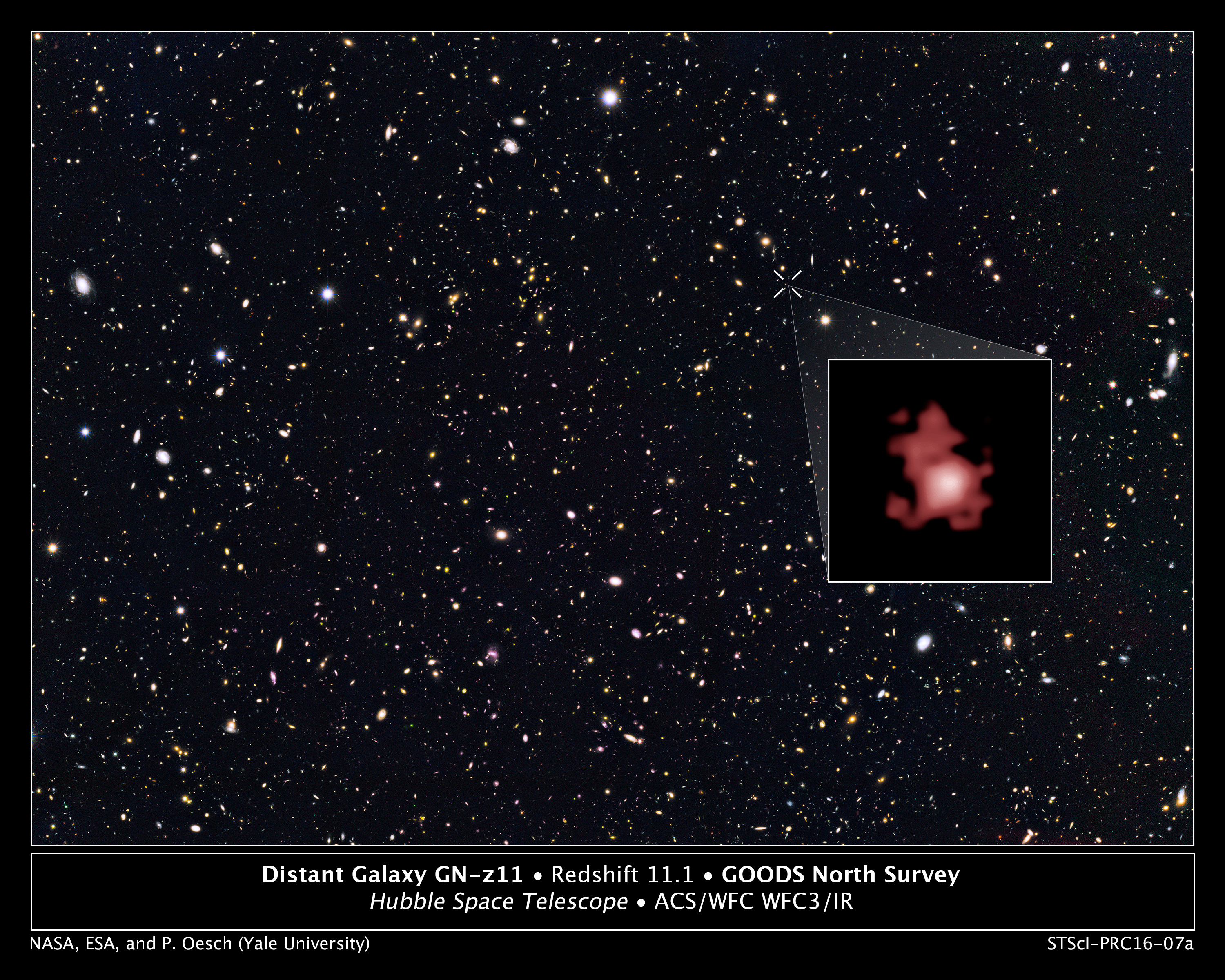

GN-z11 is the most distant galaxy observed from Earth so far. On March 3rd, 2016, NASA published an image of it taken from the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), the result of a systematic observation of deep space undertaken by an international team of researchers led by Pascal Oesch of the Observatoire de Genève.

The same month, in The Astrophysical Journal,[1] Oesch and his colleagues described GN-z11 as a galaxy with a redshift[2] of 11.09, the highest ever recorded, exceeding by a large margin the record of 8.86 that had previously been held by EGSY8p7, another distant galaxy.

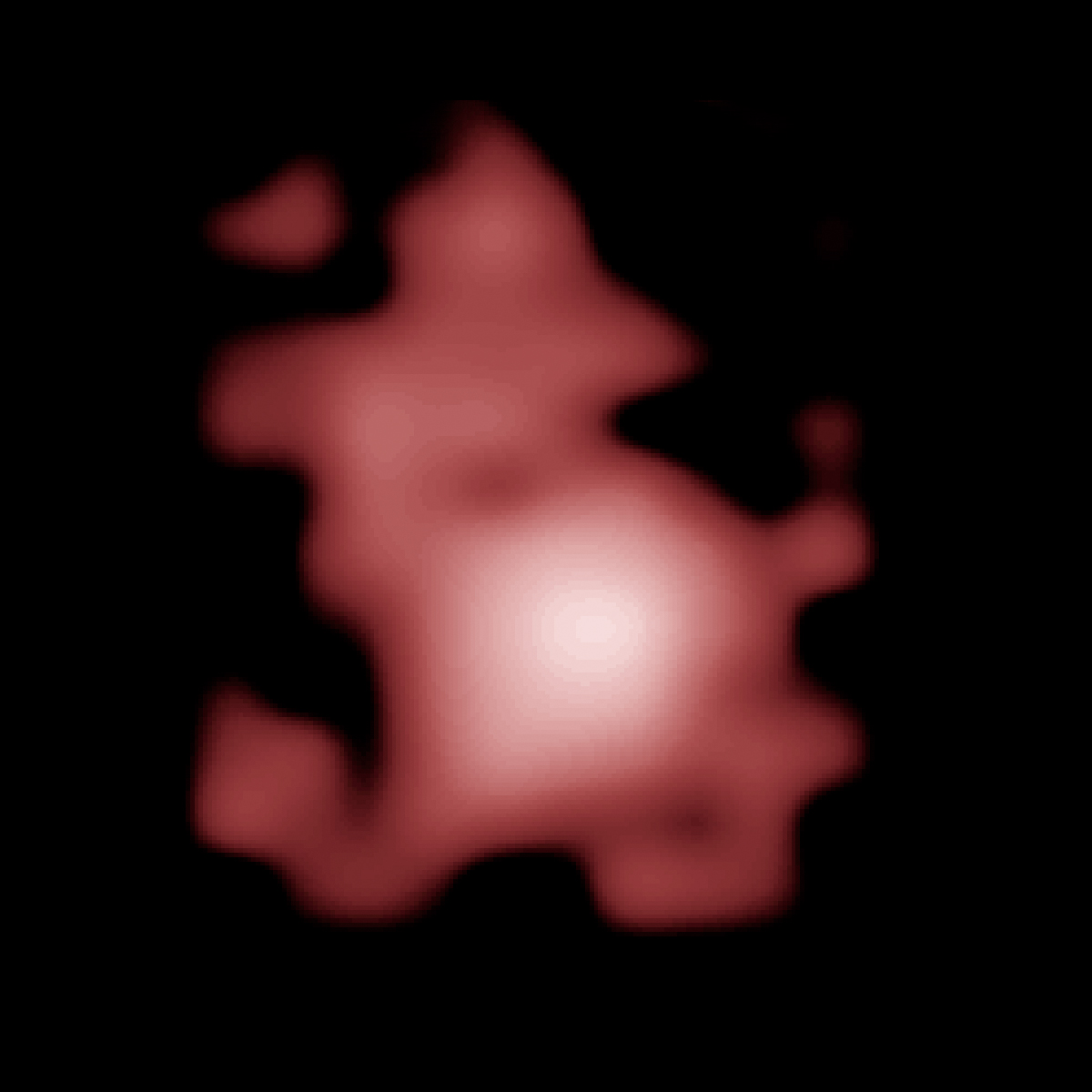

In the image made available by Hubble’s infrared Wide Field Camera 3 (known as HST>WFC3/IR), GN-z11 has the appearance of a dishomogeneous object, one with irregular borders and an archipelagic or broken spiral shape (fig. 1). Hubble photographs the galaxy within a period understood to be between the end of the Dark Ages of the universe and the beginning of the Epoch of Reionization, approximately 400 million years after the Big Bang. Situated 13.4 billion light years from us, GN-z11 is a young and relatively modestly-sized galaxy, twenty-five times smaller than the Milky Way, populated by few stars and, given its reduced dimensions, unusually luminous, likely due to the intensity of its star formation.

Let’s behold the Ursa Major (fig. 2). GN-z11 lies there, invisible, near the Ursa’s tail, north of Megrez and Alioth, stars δ and ε of the constellation.[3] Let’s behold the Ursa Major and the space extending from Megrez and Alioth. Let’s mentally isolate this space, and imagine being able to zoom so far as to make Megrez and Alioth leave our field of vision.[4] Let’s push ourselves even further, heading gently toward the northern celestial pole, penetrating the void between the stars and galaxies that we see lighting up in the distance, growing near, and finally vanishing behind us as we venture further into deep space. In that blind, dark emptiness, impossibly distant, infinitely beyond our own galaxy—that is where GN-z11 resides. What lies beyond is unknown to us. At the moment, GN-z11 is the ultimate limit of the visible, of the knowable.

Triangulating the data of various observations carried out by the WFC3/IR and the Wide Field Channel of Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys (HST>ACS/WFC), we can locate GN-z11 in a directly neighboring region of space (fig. 3).

Some of us might feel a sensation of melancholy in contemplating, in the top-right quadrant of the image, the apparent void at the center of the pointer meant to reveal GN-z11’s position, from which branches off, almost miraculously, the widening of the galaxy; a void that seems to unveil only absence, and no presence at all. Others may perceive, in addition, a particular beauty in that impression of the void, in that illusory, seemingly unnamable abyss: a remote beauty—mute, cold, intact. The same melancholy and beauty that some might feel watching the indecipherable, ectoplasmic outline of GN-z11 in Hubble’s WFC3/IR shutter.

II.

In a famous passage of his Philosophical Investigations, Ludwig Wittgenstein speaks of a “conflict” [Widerstreit] between the “rough ground” [de(r) rauh(e) Boden] of “actual language” [die tatsächliche Sprache] and the “crystalline purity of logic” [die Kristallreinheit der Logik] that, over thirty years earlier, had animated the overall project of his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.[5] The world of formal logic is described as an ideal, slippery ice-world in which it is impossible to walk, as it is frictionless. For the posthumous Wittgenstein of the Philosophical Investigations, it is precisely re-learning how to walk that is more important than anything: the reintroduction of friction and the anticipation of imperfection are necessary for a full and complete awareness of the reality of language. This made perfect sense in 1945, when Part I of the Philosophical Investigations was almost complete, and all the more so after, and even to this very day—in philosophy, as in all humanistic disciplines that, in their histories, have experienced tensions between formalist and contextualist paradigms of all sorts.

And yet, something of the cold, early twentieth-century beauty of the Tractatus seems to filter through and permeate the Philosophical Investigations, too. At the beginning of the 1990s, in the final scene of Wittgenstein, Derek Jarman stages, in an existential register, the passage from the first to the second phase of the Austrian philosopher’s thought. Partly modifying Terry Eagleton’s screenplay, Jarman illustrates the passage to the Philosophical Investigations through a fable told by John Maynard Keynes on Wittgenstein’s deathbed. Keynes tells of a very smart young man who “dreamed of reducing the world to pure logic.” The young man was so bright that he succeeded, making of the world a magnificent, endless, shimmering expanse of ice, void of any “imperfection and indeterminacy.” Moved by the desire to explore this land of ice, he realized, however, that he was unable to move even one step without falling: “[…] he had forgotten about friction. The ice was smooth and level and stainless, but you couldn’t walk there.” The young man cried bitterly. Growing and becoming an old wise man, he realized that “roughness and ambiguity aren’t imperfections” but, rather, what makes the world what it is, and that one cannot simply leave this fact aside and still hope to understand the world. Nonetheless, “[t]hough he had come to like the idea of the rough ground, he couldn’t bring himself to live there”; “something in him was still homesick for the ice,” for that lost world of his youth in which “everything was radiant and absolute and relentless.” The old man lived, in fact, “marooned between earth and ice, at home in neither. And this was the cause of all his grief.”[6]

III.

The shots of GN-z11 and the mental image of the perfect, remote ice-world of the young Wittgenstein might provoke in some of us an aesthetic experience defined by a deaf sensation of distance and loss.

There is a pure, absolute, and regressive beauty in GN-z11 and in the endless surface of ice created by the young Wittgenstein as imagined by Jarman. A beauty that is perhaps, for some, desirable once again; a beauty that seems to speak of a truth and that could play a role in a reflection on the practice of literary theory.

In its way, the literary theory of the second half of the twentieth century was, broadly speaking, dominated by the late Wittgenstein’s impulse to return to the “rough ground.” In the messy frame of post-structuralism, at least in the way it came to occupy a hegemonic position within Anglo-Saxon academic culture, the gradual falling out of favor of several (though not all) of the theoretical cornerstones of New Criticism, structuralism and, along with it, Russian formalism—the noble, early twentieth-century matrix of many successive literary-theoretical formalist approaches—was widespread. And equally widespread was the colonization of the major theoretical paradigms of the twentieth-century, psychoanalysis and Marxism above all, by the prêt-à-porter philosophical radicalism of Theory.[7]

Still within Anglo-Saxon academic culture, the affirmation of cultural and postcolonial studies in the 1970s, of New Historicism at the start of the 1980s, of Queer Theory and eco-criticism in the mid-1980s and early 1990s, and of the field of study of World Literature at the end of the 1990s and the start of the 2000s, initiated and then enabled a process involving the revision and fluidifying of many (though not all) of the axioms of twentieth-century literary theory and of critical-theoretical orthodoxies that had begun to be seen as constraints. A process of revision and fluidifying that has introduced a new and long-awaited pluralism onto the scene of literary theory, which, historically and conceptually speaking, should undoubtedly be considered an achievement.

Nonetheless, there comes a moment when, if it is prolonged in an excessive and not sufficiently critical way, the reiteration of the reasons and results of certain achievements can become rote, can become habit. What happens, then, is that these same achievements end up being themselves seen as constraints. And when history and generational distances make one lose contact with the deep roots of a form of thought, with the first, most successful results of those critical-theoretical achievements, they can come to seem empty or otherwise passé. For some, this is what is taking place, or should be taking place, in literary theory today.

It has been the case for some time now that the so-called “rough ground” on which post-structuralism had long prospered has transformed into a swamp in which it has become almost impossible to move. That is, we have come to a point in which pluralism no longer means merely cultural and cognitive richness, but also, if not especially, a form of paralysis. In order to be able to advance again, then, to be able to once again produce new knowledge, some may feel the need to start again from a solid surface and from solid categories. Some may feel, in other words, the necessity to oppose themselves once again to friction of any and all kinds, to strategically reduce the complexity of facts and multiplicity of interpretations to well-ordered shards of crystal and ice, to the clarity and harmonious motion of planets in a void. To be clear, this would hardly be done in the name of that historically forgetful and ideologically compromised form of positivism that has been the protagonist of many (not all, fortunately) major recent developments in literary theory in the context of cognitive literary studies and digital humanities, and that tends—intrinsically, but not innocently—to naturalize its own premises.

What all this amounts to is a “homesickness for ice,” a mental state and feeling of loss that makes itself into an epistemological hypothesis and develops in the fullest awareness of its regressive and “constructed” character—its “false” character, as Adorno would say—but also with the belief that it is absolutely indispensable to return to speaking of cultural objects and well-defined problems. In other words, what emerges for some is the need to go back to moving in a world that is in some sense Cartesian, governed by a logic that is newly, forcedly differential, in which spaces go back to being vertical, as well as horizontal, one in which all distances are traversable and—at least ideally—measurable. Fearing the discipline’s collapse, there is for some an urgency to try to overcome the non-hierarchical and totalizing logic of indistinction, the soul of deconstruction that had pervaded a great deal of literary theory in the latter half of the twentieth century and beyond, depriving it of essential epistemological bases that would allow it to develop in alternative directions, thus making it lose its force as model and as an at least potentially utopian force.

IV.

In dialogue with Gianluigi Simonetti about his most recent poetry collection, La pura superficie,[8] Guido Mazzoni takes up an expression coined by Stefano Colangelo,[9] describing the rewritings of Wallace Stevens present in the collection as a “distant radio station [una stazione-radio lontana],” one that allows the reader to “locate the book within a neo-modernist literary region,” to which Mazzoni thinks of himself as belonging. Despite being aware of its historical distance and the fact that, living in another epoch, modernism cannot be “precisely reinstated,” he nonetheless believes that the “radio station” of modernism “transmits to us still,” adding, almost timidly, “at least for me.” And not only for him.

Some time ago, Le parole e le cose published an excerpt of the Italian edition of The Novel-Essay, 1884-1947 and chose Black Square, Black Circle, Black Cross by Kazimir Malevich as a cover image (fig. 4).[10]

The choice of this series by the founder of the Suprematist school of abstract art, shown at the Venice Biennale in 1924, seemed particularly meaningful, since it appeared to refer, albeit subtly, to an important aspect of the book, one shared in part by The Maximalist Novel—an early-twentieth-century geometric tension. A geometric “tension,” not just, strictly speaking, a mere “geometry.” The square, the circle, and the cross in Malevich’s series are all slightly irregular and not perfectly centered on the canvas. The recurring imperfection of the geometric figures represented in the abstract works of the Russian master is a detail that would seem to allude to a type of neo-formalism that The Novel-Essay put forth, suspended between the nostalgia for a form of literary theory and a way of conceiving literary history that is essentially modern, and the awareness of the untimeliness of bringing it back in a way that would just revive its spirit when compared to the (ineluctable) epistemological pluralism and (deliberate) methodological eclecticism of the book, both markedly postmodern and, thus, foreign to that neo-formalist character. In other words, a neo-formalism that takes seriously the fact that it does not come from nothing, and, thus, does not itself fall back into nothing.

Already in the 1980s, at a time when the international landscape of literary theory was characterized by a pronounced pluralism, and up until the 2000s and 2010s, some of the best literary theorists and literary historians, often (unsurprisingly) European, have expressed—in different and, at times, strongly idiosyncratic terms—a shared sense of unease toward post-structuralist theories and methods, in continuity with a fundamentally modern theoretical tradition outside of which, in a more or less conflictual way, they have refused to locate their own work. Consider, to name a few examples, Franco Moretti’s works, from The Way of the World (English ed., 1987) to The Bourgeois (2013), Francesco Orlando’s Obsolete Objects in the Literary Imagination (English ed., 2006), Thomas Pavel’s The Lives of the Novel (English ed., 2013), as well as Mazzoni’s Theory of the Novel (English ed., 2017).

Whether we speak of neo-formalism or neo-modernism, in a given case, is of relative importance. Instead, the most important aspect is the family resemblance one notices reading these texts, the both regressive and modern “homesickness for ice” that seems to permeate them, albeit in diverse ways. It is the persistence of what we might call a strong critical-theoretical self, the attempt, in literary theory and criticism, to aspire once again, despite it all, to that “grand style”[11] Friedrich Nietzsche had already considered unattainable in his own time—which he perceived as an era of decadence—and yet one that nonetheless would influence some of the greatest achievements of modernist and post-modernist literature (from the novel-essay to the maximalist novel, from the poetry of Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot to that of Czeslaw Milosz and Joseph Brodsky), and of the literary theory and criticism of the first half of the twentieth century (from Viktor Shklovsky to György Lukács, from Mikhail Bakhtin to Erich Auerbach and Ian Watt).

Today, the modern world is both historically and axiologically distant from the one in which we live, and its revival and renewal is both unthinkable, as well as, in some respects, undesirable. The modern world is indeed a “distant radio station,” it’s true. Just like Gn-z11 is distant, infinitely distant, from the Earth. Yet not so distant, not so buried in the darkness of the northern sky, that it keeps someone from feeling the impulse or need to look toward the sky and imagine that galaxy’s light.

It is here, from this point, that perhaps literary theory could begin anew, from the gesture of lifting one’s gaze and from that impossible but necessary desire for light.

This essay has been translated into English by Dylan Montanari.

Stefano Ercolino is Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice. He taught at Yonsei University’s Underwood International College, and has been a Visiting Professor at the University of Manchester, DAAD Postdoctoral Fellow at Freie Universität Berlin, and Fulbright Scholar at Stanford University. He is the author of The Novel-Essay, 1884-1947 and The Maximalist Novel: From Thomas Pynchon’s “Gravity’s Rainbow” to Roberto Bolaño’s “2666.”

[1] P. A. Oesch, G. Brammer, P. G. van Dokkum, G. D. Illingworth, R. J. Bouwens, I. Labbé, M. Franx, I. Momcheva, M. L. N. Ashby, G. G. Fazio, V. Gonzalez, B. Holden, D. Magee, R. E. Skelton, R. Smit, L. R. Spitler, M. Trenti, and S. P. Willner, “A Remarkably Luminous Galaxy at z = 11.1 Measured with Hubble Space Telescope Grism Spectroscopy,” The Astrophysical Journal 819, no. 2 (2016): 129.

[2] Tied to the Doppler effect, redshift refers to the displacement of an astronomical object’s spectrum toward increasingly long (hence, red) wavelengths. The greater the displacement, the greater the distance and velocity with which the object moves away from the observer.

[3] Megrez is the top-left vertex of Ursa’s quadrilateral, the base of the tail. Alioth is the tail’s third star, counting from left to right.

[4] As can be seen here, for example: http://hubblesite.org/video/798.

[5] L. Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations [1953], eds. G. E. M. Anscombe and R. Rhees, trans. G. E. M. Anscombe (Oxford: Blackwell, 1997), 46.

[6] T. Eagleton and D. Jarman, Wittgenstein: The Terry Eagleton Script, the Derek Jarman Film (London: BFI, 1993), 142. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7TM0zA2_5UE.

[7] See B. Carnevali, “Against Theory,” The Brooklyn Rail, 1 September 2016, available online at https://brooklynrail.org/2016/09/criticspage/against-theory.

[8] G. Simonetti, “Mondi e superfici: Un dialogo con Guido Mazzoni,” Nuovi argomenti, 30 October 2017, available online at http://www.nuoviargomenti.net/poesie/mondi-e-superfici-un-dialogo-con-guido-mazzoni/.

[9] S. Colangelo, “Le cose che arrivano, senza protezioni,” Alias domenica, 8 October 2017, available online at https://www.donzelli.it/download.php?id=VTJGc2RHVmtYMStLL3o4Wm80ZjhGRHlnck9nWW13QlZ1dXRzR21OVVBkST0=.

[10] S. Ercolino, “Il romanzo-saggio,” Le parole e le cose, 25 June 2017, available online at http://www.leparoleelecose.it/?p=28115.

[11] “The greatness of an artist cannot be measured by the “beautiful feelings” he arouses […]. But according to the degree to which he approaches the grand style [(s)ondern nach dem Grade, in dem er sich dem großen Stile nähert], to which he is capable of the grand style. This style has this in common with great passion, that it disdains to please; that it forgets to persuade; that it commands; that it wills [daß er befiehlt; daß er will]—To become master of the chaos one is; to compel one’s chaos to become form: to become logical, simple, unambiguous, mathematics, law—that is the grand ambition here.—It repels; such men of force are no longer loved—a desert spreads around them, a silence, a fear as in the presence of some great sacrilege—All the arts know such aspirants to the grand style […]”; Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power [1906], ed. Walter Kaufmann, trans. Walter Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale (New York: Vintage, 1968), 443–44; Friedrich Nietzsche, Nachgelassene Fragmente, 1887–1889. Kritische Studienausgabe, eds. G. Colli and M. Montinari, vol. 13 (Munich/Berlin-New York: DTV/de Gruyter, 1999), 246–47.