This essay has been peer-reviewed by the b2o editorial collective.

by Mimi Howard

In Freiburg 1919, Martin Heidegger explained in a lecture on phenomenology that everyone in the room had a functional relationship to a lectern that stands before him. It is not simply a box but an object that occasions a particular etiquette, something that calls forth certain rituals of social conduct. In a boiler-plate illustration of perspectivism, Heidegger then asked the room to imagine that a “Senegalese Negro” is suddenly planted before them. This troubles the whole arrangement, Heidegger claimed, because he would not know what to make of this lectern at all. Further, there is no way for Heidegger to access his perception, given that “my seeing and that of the Senegalese Negro [Senegalneger] are totally disparate [grundverschieden]” (Heidegger 1987, 72).

The German lectern, a neat stand-in for the enterprise of knowledge production, is possibly meaningful, is a possible object of phenomenological description, only because its value is culturally determined according to pre-existing conditions into which ‘we’ have been ‘thrown’. But something else is at work here. When Heidegger performs this self-imposed delimitation of phenomenology’s remit, blackness gets figured as the horizon-line of philosophical inquiry, marking out a constitutive edge where the study of ‘things in themselves’ falls short, fails to answer a question, or ceases to formulate one. Such epistemic failures flag up the relation between phenomenology and ontology, the region of inquiry towards which Heidegger’s would turn in later work, largely in attempt to address precisely the fundamental underlayers of experience that are resistant, or unavailable, to phenomenological description.

In the past years, Fred Moten has been concerned with parsing the interrelation between blackness and ontology, tacitly interrogating the legacy of Frantz Fanon’s famous claim that “ontology—once it is finally admitted as leaving existence by the wayside—does not permit us to understand the being of the black man” (Fanon 1986). Fanon’s insights have been a provocative starting point for black studies in recent years, particularly for Afro-pessimist thinkers like Jared Sexton and Frank B. Wilderson. According to their purview, blackness is contained precisely within the impasse that Fanon described, within a “political ontology” whose ground is always-already constituted by a refusal of the “being of the black man.” As Wilderson has put it, black people are thereby assigned to “a structural position of noncommunicability” that countersigns the safeguarding of ideal subject-citizens (Wilderson 2010).

The Afro-pessimistic appeal to political ontology has arisen alongside similar tendencies in ‘continental’ political philosophy. Since at least the end of the post-war period, political theorists have struggled with the problem of how to ground their analyses after the expulsion of God, progressivist history, and Enlightenment reason from the philosophical toolkit. In the intervening decades, the task at hand has been to cobble together a framework that holds onto some faith in political praxis while rejecting the predication of that praxis on some transcendental a priori. Heidegger’s ontology has been revived as an antidote to this absence of bannisters (to use Hannah Arendt’s famous phrase). His schematization of groundlessness, contingency, and non-identity of the subject has proven a powerful paradigm for partisans of post-foundationalism. This resurgence of Heideggerian ontology has gained traction enough to have some declare an ‘ontological turn’ (Marchart et al., 2017).

Political ontology has been especially attractive to some anti-liberal theorists for a few reasons. (As Bruno Bosteel’s has noted, though many political ontologists claim to be leftist, there is nothing formally emancipatory about an ontological approach to politics.) From a methodological perspective, toward traditional questions about liberty, justice, or the good life, a political-ontological framework allows for spontaneous human action to become the center of analysis. Ontology ostensibly shifts the political-philosophical gaze towards the conflictual, dynamic, and improvisatory nature of politics ‘on the ground’, serving as rejoinder to liberal political philosophy and its hawk-eye view of the State and its Citizens. In contrast to this liberal paradigm, political ontologists declare a low threshold for what constitutes political action, and thereby pluralize the kinds of possible political subjects. In the words of one if its preeminent theorists: “Every action becomes politics when it at least is touched by antagonism” (Marchart 2010, quoted in Saar 2012).

The ontological character of antagonism is equally important to the Afro-pessimistic framework. According to Wilderson’s influential paradigm, the historical appearance of slavery develops a new “ontological category” whereby political discourses became predicated on grammars of antagonism, “forging a symbiosis between the political ontology of the Human and the social death of Blacks” (Wilderson 2010). Ontology’s refusal to think blackness is thereby inextricable from structural, historical anti-blackness. Yet, in agonistic tandem, Moten has wondered whether the turning of Fanon’s insight into the basis of a ‘political ontology’ has a productive function; if it boxes itself into, and to some extent supports, the world of the “artificial, officially assumed position” it would want to rebuke (Moten 2013a, 741).

To endorse a political ontology that describes the refusal of black being is to support an epistemological regime that participates in co-creating the world after political theory’s image (citizens, power, sovereignty, etc.). Without throwing Afro-pessimism’s envisioning of anti-black racism by the wayside, Moten asks if it is possible to depose the reigning political-ontological framework, a framework wherein “blackness and antiblackness remain in brutally antisocial structural support of one another like the stanchions of an absent bridge of lost desire.” (Moten 2013a, 749). Ontology, from Moten’s standpoint, is not just unable to think antiblackness, but rather produced and given by that incapacity. His task, contra Fanon and contemporary theorists, is then to “refuse subjection to ontology’s sanction against the very idea of black subjectivity,” by exhausting ontology itself (Moten 2013a, 749). What would it mean, Moten asks, “to desire the something other than transcendental subjectivity that is called nothing?” (Moten 2013a, 778)

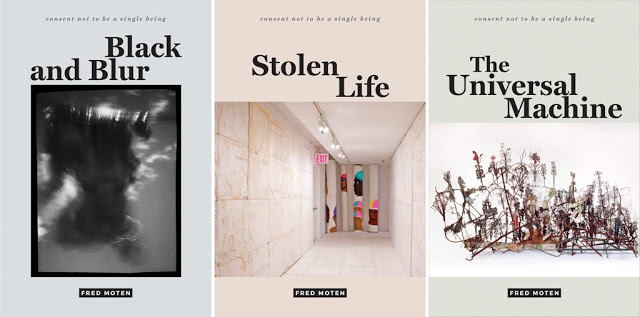

This intervention, and injunction, to ‘exhaust’ ontology’s special claim to ‘the political’ is sustained by Moten’s approach to a form of theoretical writing that re-formulates the task of critical philosophy, while also contesting political ontology’s ‘pessimistic’ aversion to Marxist tradition, showing that one need not dispense with dialectics in favor of static Manichaeism. The following review attempts to trace (by no means comprehensively) how Moten has continued to unfold this argument over the course of more than a decade of writing, collected in the recently-published three-volume series consent not to be a single being (2018), paying particular attention to the way that he intervenes in debates in contemporary political and critical theory.

***

consent not to be a single being, titled after a phrase of Édouard Glissant’s, ranges across an impressive number of disciplines: black studies, performance studies, aesthetics, phenomenology, ontology, ethnomusicology, jazz history, comparative literature, critical theory, etc. Without announcing its intervention as interdisciplinary–Moten deftly renders discipline beside the point. Instead, his “devotional practice” explicitly proceeds with heart, not quite stopping long enough to fix upon, objectify, or possess the shifting locus of study. The goal, in fact, is the contrary. As he writes in the preface to the trilogy’s opener Black and Blur, this is a celebration of the “animaterial operation-in-exhabitation of diffusion and entanglement, marking the displacement of being and singularity” that is blackness (BB, xiii).

As Deleuze and Guattari would have it, liberated desire is difficult to pin down. Unlike popular desire, encoded by the flows of capitalism, liberated desire eludes authority and escapes the “impasse of private fantasy” (Deleuze & Guattari, 2009). Desire’s amorphous capacity is its genius—to get plugged into different outlets, to reemerge through collective expression. You know it, in other words, when you don’t see it. Moten’s books capture something similar. His is a language that resists appropriation but has, paradoxically, become companionable to a great many projects. (One wonders how many reading groups have indebted themselves to Moten and collaborator Stefano Harney’s idea of the “undercommons”; few figures are as dear to activists, academics, and artists alike.) Ultimately, the zeal for Moten says as much about him as it does about our moment—desire for a politics beyond sanctioned discourse, sociality salvaged from social media, and, maybe most of all, some vindication that the lives we create under the noses of capital might already imagine another world.

Harney and Moten’s The Undercommons (2013), a widely shared and beloved book, was marked by an activist lyricism (“I just need you to recognize that this shit is killing you, too, however much more softly, you stupid motherfucker”). The essays of cntbsb similarly pair philosophical questioning with sonorous phrasing. Though Moten aligns himself with the black radical tradition, his particular voice is reminiscent of none of its famous luminaries. Thankfully the right to write like he does is never made the subject of its own analysis. Unlike with Derrida or Spivak or Lacan or Heidegger, resistance to clarity is not in the service of a meta-point about the trace of writing, or the restaging of knowledge’s limit. Rather, as with the jam session, everything is already going on at once. As readers, we’re along for the ride; feeling out the repetitions until they become concepts behind our backs, carrying provisional definitions until they get displaced, rejigged, and transformed anew from page to page.

On the whole, the series is a veneration of friendship and the unproprietary nature of thought. Moten continually lays his cards on the table, and his co-conspirators are called out in the body of the text: he’s “thinking along with” Hartman, “moving by way of” Mackey, “being taught” by Miyoshi and José (Muñoz)—indeed, in an interview, Moten has called this writing a form of name-dropping (Moten 2004).[1] But it’s also an ode to adversaries. We’re told at one point that “Mingus was a genius at showing contempt” (BB, 88) and perhaps the same can be said of Moten himself. Contemporary thinkers like Bryan Wagner, Catherine Malabou, and Eric Santner, Giorgio Agamben are put at affable risk. Paul Gilroy receives exasperated rebuttal in a particularly memorable footnote. Neither do earlier thinkers like Immanuel Kant, Hannah Arendt, Emmanuel Levinas, and Fanon emerge unscathed. They do emerge, however, irreparably transformed.

cntbsb is not the product of one Fred Moten, but the result of an evolution across fifteen-odd years, written for a variety of academic and artist publications that display Moten’s ability to shift genre. Still, each of the books have, if not a particular focus, then something of a mood. Black and Blur concerns the status of creative life (especially visual and musical art) under capitalism. Stolen Life breathes force into the philosophy of subjectivity and acts as a sustained struggle with the kinds of philosophical questions that also animate a range of black thinkers. The Universal Machine offers a rigorous deconstruction of post-war phenomenological thought, pivoting around brilliant engagements with Emmanuel Levinas, Hannah Arendt, and Frantz Fanon. Taken together, the series amounts to a powerful argument for black study—as an analytic, an impetus, a mode, the collective shout from a radical vista, whose bellow requires nothing less than “passionate response” (Moten 2003).

***

Primarily concerned with art, literature, music, performance, and the black radical tradition, Moten’s Black and Blur picks up where In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical (2003) left off. There are certainly some points of overlap—Cecil Taylor, Charles Mingus, Cedric Robinson and Immanuel Kant are important figures in both. But Black and Blur is not just a continuation, it’s also a corrective. Moten tells us at the outset that the essays collected in the entire series are an attempt to figure out what’s wrong with the opening sentence of In the Break: “the history of blackness is a testament to the fact that objects can and do resist.” That sentence, over which Moten claims to have suffered in the intervening fifteen or so years, should have read: “Performance is the resistance of the object. The history of blackness is a testament to the fact that objects can and do resist.”

What exactly has changed here? Parsing the difference brings us back to the disagreement that Moten has staged with Afro-pessimism. Moten concedes that his original statement “blackness is x” submits to the claim that the study of blackness must necessarily move within the political-ontological field that has already defined blackness as objectivity. In the Afropessimist Frank Wilderson’s words, there is an unbridgeable gap between the ontological status of “the Human as an alienated and exploited subject” and of “Blacks as accumulated and fungible objects” (Wilderson 2010). This realist dichotomy necessarily undergirds any study or analysis of black life. Moten doesn’t totally disagree. He says that the “weight of anti-blackness upon the general project of black study” is also the very thing that animates and enables the “devotional practice” that he wants to put forth (BB, viii).

Still, this is something more than devotional practice. Moten writes:

to be committed to the anti- and ante- categorical predication of blackness—even as such engagement moves by way of what Mackey calls “an eruptive critique of predication’s rickety spin rewound as endowment,” even in order to seek the anticipatory changes that evade what Sadiya Hartman calls “the incompatible predications of the freed”—is to subordinate, by a measure so small that it constitutes measure’s eclipse, the critical analysis of anti-blackness to the celebratory analysis of blackness.” (B&B, viii, emphasis added).

Herein lies the double movement of Moten’s (corrected) project. First he treats critically, and committedly, the way in which blackness is predicated through anti-blackness, but also turns (as Marx did Hegel) that construction on its head. What if, after Nathaniel Mackey, predication was spun back around, so that the ground of the political ontology that gives blackness through anti-blackness could be shifted? This inversion consists in subordinating Afro-pessimism (the critical analysis of anti-blackness), to Moten’s black optimism (the celebratory analysis of blackness). Celebration, then, means seeing how black art predicates. “Mobilized in predication,” Moten writes, “blackness mobilizes predication not only against but also before itself” (BB, viii). One need not begin with the ontological given of anti-blackness then, but see how blackness comes prior to the givenness, how it gives the given.

Illustrating this ‘anoriginality’ by way of movement through black art, literature, and music propels the book forward. The opening chapter “Not-in-Between” is representative here, a kind of synecdoche that contains threads of the argument that are woven through the rest of the text. He moves through Patrice Lumumba, C. L. R James, and Cedric Robinson to outline nothing less than a new post-colonial philosophy of history. Moten takes James’s The Black Jacobins as a form of history-writing that theorizes its own limits by interweaving lyric with the official discourse of historical narrative. James’s lyricism marks the entry of a kind of black radical corrective to Hegelian historical struggle—a transfiguration of “dialect into dialectic.” Moten argues that James’s historico-radical writing is embodied in such “ancient and unprecedented phrasing,” which mark the impossibility of a “return to Africa that is not antifoundationalist but improvisatory of foundations” (BB, 13). Of course, Moten is describing his own combination of verse and prose here too, employing form to ask how one can tell a story without origins, without grounds (and without ontological predication).

Unlike the other two books in consent not to be, Black and Blur consists of many short chapters, some of which were originally written as essays for artist monographs. It’s no coincidence that this is the book has already been taken up by the art world—understandably hungry for something different amidst the long reign of Adorno. Thankfully, Moten has a lot to offer by way of new theoretical horizons, and Adorno explicitly forms the antagonistic point of departure. In one chapter, Adorno’s dismissal of popular music as the functionalist “culinary” byproduct of capital is swallowed up by Moten’s analysis of two cultural products: “Ghetto Superstar” (1998), a single performed by Pras, ODB, and Mya, as well as an attendant novel co-written by Pras and kris ex. The book version contains a scene that mimics almost precisely Louis Althusser’s famous description of interpellation. The protagonist Diamond St. James recognizes an old security guard at his high-school, now community cop, but doesn’t allow himself to be ‘interpellated’ and gives the officer a fake number. In this refusal, Moten argues that Diamond is the “sentient, sounding object of a powerful gaze” and as such a prime example of what Moten has been interested in since In the Break: the “becoming-object of the object, this resistance of performance that is (black) performance.” (BB, 33).

This celebration of the object’s resistance forms the basis of Moten’s disagreement with Adorno. Moten later contests Adorno’s distaste for the infiltration of cinematic qualities–repetition, syncopation, and sequence–into music with an appreciation of Glen Gould’s “montagic” performance an actor and pianist. Yet another chapter continues this line of thought, but this time in tandem with photographic representations of black female bodies. Here Moten takes issue with Adorno’s definition of music as the only ‘temporal’ art, aiming to show how the resistance of the photographic subject embodies the lapse of time through fugitivity. Summing up the thrust of both his debt and contest to Adorno’s aesthetics, Moten responds to Adorno’s famous distaste for jazz exclaiming: “How unfortunate for Adorno that the music one most loathes might best exemplify the fugitive impetus one most loves!” (BB, 85)

After the first half of the book, a kind of breakdown occurs—signaling that the contestation with Adorno is over and we’ve moved (by measure’s eclipse) from the critique of anti-blackness into celebration. The pace runs a bit quicker, with a new numbering scheme that unites subsections through chapters, and formalizes the assembly-like character of the whole enterprise. Now come texts dealing more particularly with the artwork, music, and literature of contemporary figures: Theaster Gates, Thornton Dial, Adrian Piper, Oscar Zeta Acosta, Ben Hall, Rakim, and many others. This is where the party begins, and where Moten is dealing explicitly with what celebration means: “Celebration lets being-special go, but under an absolute duress” he writes. Moten argues that the artwork has no tendency towards redemption, promises no final salvation. Rather art’s worth lies in the permission it grants to cross oneself out, to activate and realize Marx’s living commodity in a way he never imagined—to be, or become, “a changing object called object changers” (BB, 222).

Is this perhaps too optimistic, too crudely dialectical a view of what black art can do? Moten anticipates such contentions in the preface. Speaking to his (pessimistic) detractors, he writes:

Some have been content to invoke the notion of the traumatic event and its repetition to preserve the appeal to the very idea of redress even after it is shown to be impossible. This is the aporia some might think I seek to fill by invoking black art. Jazz does not disappear the problem; it is the problem, and will not disappear. (BB, xii)

Black & Blur is not about recovery, redress, and rejoicing. It is certainly not about ‘uplift’ (the idea is a focus of a chapter in Stolen Life). It is about dwelling in the aporia of slavery as a “philosophically-induced conundrum,” a problem that has been made so by unjustifiable “metaphysical and mechanical assumptions.” Blackness is a problem, Moten tells us, which derives not from “redress’s impossibility” as Afro-pessimists would have it, but rather from the obliteration of commonplace formulations, the overall inordinacy of thought’s self-expression. It is art’s task to illuminate that inordinacy; and it’s the duty of black study to celebrate its effort.

***

Stolen Life takes thought’s limitation as its starting point. After Cedric Robinson’s definition of the black radical tradition as a contestation of Enlightenment, Moten moves through an interrogation of staid philosophical standards to unleash a “radical social imaginary” that flies in the face of traditional political theory. As he writes, wants to effect “the reversal of an all-but-canonical valorization of the political over the social” (SL, xii). Much of the book has to do then with sociality and learning, including an essay drawn from a letter to one of his classes. Another concerns the task of black study. Another powerfully asserts the role of the academy in the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement.

A rare low moment in the series occurs with Moten’s Derridean paean to Avital Ronell. Moten presents fragments of their near-misses and close calls; first as colleagues at Berkeley and, flashing-forward, today at New York University (where Ronell will, amid protest, resume her position this Fall). There is an explicit uneasiness thematized here, and one wonders toward what end, exactly? Moten notes that he’s “embarrassed” to be talking about himself when he should be writing about Ronell, but he’s “incapable of that separation” between him and her. Comparisons between Ronell and his mother abound, complete with Freudian slippages. “All that was just to say that I never have been and never will be either willing or able to separate myself from this paragraph,” Moten writes in close before quoting Ronell’s Telephone Book (SL, 239). Even disregarding the recent revelations of Ronell’s abuse of professorial power, there’s something unsavory here. Surely lots of Moten’s project has to do with the attempt to inject something like care into intellectual life – but at what cost? The essay serves as a reminder that Moten’s intervention takes place against the backdrop of systemic complicity and corruptions in academia; something can’t simply be addressed with “embarrassed” Derridean adoration, but with institutional safety and support that explicitly refuses charismatic models of intellectual intimacy.

Nonetheless, the Ronell episode does not detract much from the main event. If Adorno was the primary target of Black & Blur, Moten is more occupied with Kant’s legacy here. Phantom-like, he also occupies Kant, moving within him to tease out his grittiest internal contradictions and limits, showing the breakage of the outside into his system of philosophical criticism. Moten speaks to the legacy of modern philosophy more generally, with its concomitant models of freedom, justice, knowledge, transcendental subjectivity, cosmopolitanism—the “metaphysical and mechanical presuppositions” whose overturning were prepared in Black and Blur. As he writes in the preface, blackness “anticipates and discomposes the harsh glare of clear-eyed (supposedly, impossibly) originary correction, where enlightenment and darkness, blindness and insight, hypervisibility, converge in the open obscurity of a field of study and a line of flight” (SL, x). Philosophical tradition can be neither corrected nor redeemed; but it can be probed to open out the lines of flight, forms of resistance, that emerge from the parallaxing gaze of black study.

Moten richly thematizes this interplay in the remarkable first chapter “Knowledge of Freedom,” altered from an article originally published in 2004. Following the work of Winfried Menninghaus, he looks at how Kant’s definition of reason admits the existence of an irrational surplus; a notion of rational understanding that requires we “clip the wings” of imagination. According to Moten’s gloss, this sacrifice leads Menninghaus to identify a “politics of curtailment” and policing in Kant that shows how the latter also apprehends “the prior resistance (unruly sociality, anarchic syntax, extrasensical poetics) to that politics it calls into being” (SL, 2). Moten is interested in how Kant is playing himself. He writes:

To engage Kant, our enemy and our friend, is to be held and liberated by the necessity of alternative frequencies, carrying signal and noise, that thinking blackness–which is what it is to be given to the reconstruction of imposition–imposes upon him as well. An already-given remix of the doctrinal enunciation of the end is amplified and he becomes our open instrument. (SL, 10)

How does blackness put pressure on Kant, and how is that pressure self-imposed and presupposed by Kant himself? Sitting with Kant’s philosophy of race can release an alternate frequency of blackness that enables another possible definition of freedom, one that acts in resistance to critical regulation. There is, Moten proposes, a “radical sociality of the imagination” that acts as the spectral prelude to Kant’s carceral philosophy.

By ventriloquizing a “black chant” through Kant, Moten puts forth a vision of what critical theorists might call immanent critique. As Titus Stahl has recently put it, this is the kind of critique that derives “the standards it employs from the object criticized,” an attractive tool of successive generations of Critical Theorists given that it does not need to theorize norms into existence. Thus, immanent critique does not imbue the theorist with the superpower of an Archimedean moral vantage point, but rather uses those immanent to society as a way to parcel out critical judgements (Stahl 2013). Moten writes, in echo: “all that intellectual descent neither opposes nor follows from dissent but, rather, gives it a chance.” We would do well to see the ways in which our inherited concepts give us the tools for dissension.

Moten is, however, resistant to the ways in which critique has also been a vehicle for “sovereign regulation and constitutive correction.” As he writes in the preface, “certain critico-redemptive projects” are content to “submit to a poetics of condensation and displacement when blackness, which already was an was always moving and being moved, stakes its claim as normativity’s condition” (SL, x). In riposte to critical theory, and to Kantian criticism, Moten is asking us where normativity comes from, and if we should truly like to use it as a moral measure. As he states powerfully throughout the book and series, the very conditions for norms and values are predicated and figured through the thought of blackness as pathogen, generativity, irrationality and formlessness. The question then, is of seeing “how the generative breaks into the normative discourses that it found(ed)” (SL, xi), of seeing the escape, insurgency, and “irreducible sociality” of black life which both disrupts and gives the given paradigm.

Moten sharpens this point by pitting himself against historicizing theorists like Bryan Wagner, who has looked at what blackness comes to mean against the backdrop of the law. Wagner has argued that blackness indicates a certain set of qualities that appear when looking at its juridical regulation. As with the appraisal of Afro-pessimist political ontology, Moten argues that there is a category mistake going on. “Being black in Wagner’s more self-contained Fanonian formulation is an anti- or non-subjective condition” that precludes one from having standing in the world system (SL, 24). According to Moten, Wagner et al. have forgotten what Heidegger called the ontological difference between Being and beings, or more precisely, what Chandler calls the paraonotological difference between blackness and black people. “Wagner writes,” Moten says, “from a position that many contemporary critics now occupy, a position structured by this presumed incapacity for ontological resistance.” Such a presumption, or assumption of rigidity, allows theorists to suspend the analysis of ontology and forego any inquiry into “the pressure that blackness puts on both ontology and relation” (SL, 24).

To get at this pressure, Moten invokes Chandler’s paraontological difference to show that the actual standing (the “facticity”) of black people is not the same as the ways in which blackness is seen through the eyes of the state. “The history of blackness,” Moten writes, “can be traced to no such putatively, and paradoxically, originary critical or legal activity. (SL, 28). Following Frege and Mackey’s “eruptive critique of predication’s rickety spin rewound as endowment,” Moten suggests that there is instead something called blackness “that has, itself, in turn, been altered by that to which it refers”—a referent that exists before its naming, a primordial and shifting being – of displacement, generativity, and fugitivity (SL 23). Amid a long lineage of debates in black studies about the status about what kind of ‘thing’ blackness ‘is’, whether it is in Michelle Wright’s words “in the eyes of the beholder or the performer,” Chandler’s paraonotological difference permits both readings simultaneously (Wright 2015).

Still, an unfathomable task remains; that of trying to imagine a phenomenology that moves beyond the relational polarity between self and other, subject and object, sovereign and citizen. These are the binaries that also organize political philosophy, and the ways in which we can possibly imagine ‘agents’ in the first place. Moten notes that the dismantling of such categories has been the focus of a number of thinkers, including Fanon and Merleau-Ponty, Agamben, and most recently Catherine Malabou. Malabou (along with others in the New Materialist vein) has sought to dethrone the concept sovereignty from political philosophy by collapsing the split between the “King’s two bodies,” between the material and transcendental. Yet as Moten persuasively argues, Malabou’s reliance on biology or neuroscience has also inadvertently allowed her theory of “plasticity” to reinscribe the brain as ‘sovereign’ over the body. Who gets to have a body in any case? Who are the ‘we’ who possess ourselves over and against our own bodies? Borrowing instead from Hortense Spiller’s distinction between the body and the flesh, Moten presents a notion of flesh-in-displacement, a kind of reinvigoration or reanimation of (a warily-) humanist materialism. Perhaps we don’t need new-fangled philosophical tools at all, but rather a phenomenology that could finally take seriously the so-called thing in itself that it claims to study.

***

The Universal Machine sets the task of re-imagining post-war phenomenology. It is, in Moten’s words, a “monograph discomposed,” a (Deleuzian) “swarm” containing three essays on Levinas, Arendt and Fanon (UM, ix). In a lucent intervention into the history and legacy of twentieth-century philosophy, Moten returns to those thorny subjects and objects that had troubled him in Stolen Life, whittling phenomenology into an estranging shape rather than discarding it completely. Mobilizing an idea of swarm—an composite of ontology, phenomenology, and politics—Moten’s aim is then a semi-reparative one: “not so much antithetical to the rich set of variations of phenomenological regard; rather, it is phenomenology’s exhaust and exhaustion” (UM, ix).

Moten gives exhaust provisional form. It is embodied by figures who have put forth a “dissident strain in modern phenomenology.” Edmund Husserl, he claims, is phenomenology’s exhaust, so too are Levinas, Arendt, and Fanon. That’s to say that their thinking takes place beyond subjectivity’s pale; they “operate under the shadow of a question concerning humanity that they cannot assume” (UM, xi). As with his critique of Kant’s legacy, Moten argues that phenomenology provides us with all the tools we need to think otherwise. It’s just a matter, after Deleuze’s explication, of exhausting the possible through the art of “the combinatorial” (Deleuze 1995).

The opening chapter of the book takes flight from a remarkable epigraph. In an interview concerning his relation to Heidegger and the phenomenological tradition, Emmanuel Levinas remarks that “the Bible and the Greeks present the only serious issues in human life; everything else is dancing. I think these texts are open to the whole world. There is no racism intended” (UM, 1). In keeping with Deleuze’s combinatorial spirit, Moten considers the implications of this claim in several different directions. First, he asseses Levinas’s Eurocentric conception of the Other, which is tethered to Levinas’s tautological belief in the heritage of the Bible and the Greeks. Levinas’s famous face-to-face encounters, Moten writes, “are mediated by a highly circumscribed textual canon and by whatever force is deployed to open the world to the texts that he declares are open to the world.” (UM, 19).

Moten further explores the consequences of Levinas’s “unintended racism” by looking at the very status of intention in phenomenology. Though phenomenology usually concerns the ‘intentionality’ of human consciousness towards an object – were are always conscious ‘of’ something, or have an experience ‘of’ something – Moten argues that racism resides precisely in a “fundamental unintendeness,” or the failure of phenomenology to attend to the humanity of things (UM, 17). Moten’s injunction to ‘return to the thing’ thereby draws upon other recent attempts to overcome a supposedly recalcitrant Cartesian dualism, especially among theorists working on the proximity between human and animal life like Giorgio Agamben and Eric Santner.

Yet Moten objects to what Santner has conceptualized as “creaturely life”:

If Agamben and Santner are right to suggest an interplay, at the border, between inside and outside, then perhaps it would be, as it were more right to consider that the internal and the external presuppose one another within the general field—or, if you will, the borderless surround, the common underground–of the out from outside. My point is the necessity of imagining a productive difference, a political differing, a differential city or city-ing, that is irreducible to the distinction between friend and enemy. (UM, 41)

Santner, pace Agamben and Heidegger, views the creaturely as the “threshold” at which point life takes on a biopolitical intensity. Moten, in contrast, wants to “identify not with the creaturely life but the stolen life of imagining things” (UM, 57). Moten’s identification permits a different vision; not of a life animated by its entrance into ‘the political,’ but a life that refuses being called into being by a sovereign power. “There is,” he writes, “an insistent previousness that evades the natal occasion of the state’s interpellative call” (UM, 44). In rehearsal of his general dissatisfaction with political ontology, Moten is interested, he clarifies, in “what there is before the throw, before the call” (UM, 34), and demonstrates that this prior refusal is thinkable by engaging with the black radical tradition, conspicuously absent from Agamben’s corpus.

By way of Moten’s discussion of natality, the space of the political, friends and enemies, we also move, necessarily, towards Hannah Arendt. The second chapter presents a vision of her blurred beyond recognition. Building on recent work concerning the force of racism in Arendt’s thought, Moten’s criticism of Arendt is roughly organized through two sets of letters written by her. The first is to Mary McCarthy, in which Arendt privately bemoans the threat posed when “Negros demand their own curriculum without the exacting standards of white society” (UM, 72, letter quoted in Young-Bruehl 2004). This sentiment was also given public form in Arendt’s 1959 essay “Reflections on Little Rock,” which she opens by discussing the famous image of Elizabeth Eckford on her way to school. Arendt writes (and Moten claims we ought to speak of her in the present tense given her hold on American intellectual and political life today), “Under no circumstances would I expose my child to conditions which made it appear as though it wanted to push its way into a group where it was not wanted” (UM, 75).

Moten discusses Eckford’s performance in relation to a performance piece by artist Adrian Piper in 1970, in which she entered famed art bar Max’s Kansas City, letting herself be absorbed into the environment as a “silent, secret, passive object” (Piper quoted in UM, 81), Moten shows that Arendt is incapable of thinking the transformative capacity of dwelling, as Piper does, in a “sly alterity.” What Arendt opposes, and refuses to see, in short, is black study. This was made explicit in On Violence when she expressed a distaste for so-called “soul courses.” But, as Moten argues, this is not just a curricular dispute. Arendt’s opposition is also connected to the ways in which she valorizes and emblematizes a certain kind of intelligence. She insists being intelligent is a moral matter—as she famously said, we have to “think what we are doing.”

This insistence, Moten claims, is connected to yet another: Arendt’s dogged belief that there is something called “politics” that it needs to be thought of in particular ways. A letter written to James Baldwin, in the aftermath of the publication of his “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind” in the 1960s illustrates this. Despite calling his essay a “political event of a very high order,” Arendt claims that Baldwin’s faith in love is misplaced— “in politics,” she writes, “love is a stranger” (UM, 84). Love is not a political concept, Arendt argues. Moten retorts: Baldwin was not a political theorist.

By this point, we are unsure if something called politics can possibly exist, a practice and ritual that would be unthinkable without the presupposition of the modern liberal paradigm. As Moten asks, can political theory ever be severed from Kantian categories—from a critical, critically-delimited notion of what reason itself can do aside from ‘putting itself on trial’? What if our frameworks for interpretation are presumptive beyond repair? The breakdown of all of these questions resounds in a powerful denouement. Moten shifts from the Arendtian polis to the undercommon social realm, by way of a formal innovation that he sometimes calls aesthetic/poetic sociology, or social poetics. It is a turn towards appreciating and celebrating the activities which occur at the “underbreath” of the polis, activities that threaten the “normative order the city can be said to have agreed upon” (UM, 103). It is a science (or art?) of looking at relations of nonrelationality.

I’m wary, at moments, that Moten’s aesthetic-sociological backdoor depends upon the strawman of a totalizing ‘political sphere’ as its counterimage, presented here in terms of rhetorical reliance upon, or a willful caricature of, Arendt as its systematic theorist. This leaves Moten to the simple task of transvaluating the values, flipping Arendt’s hatred of sociality into the non-normativity we should celebrate. (If we want to do away with political ontology, let’s do away too with the idea of an ontological polis!) We are perhaps left to wonder if this approaches a dichotomous political order, achieved in a similar if anterior way to the political ontological equilibrium of Afro-pessimistic realism. If phenomenology is the thing to be revived here, the relation between law and lawlessness, polis and undercommon, could stand to be a bit more dialectical. Does Moten’s thought have room for Geist, or has he rejected a speculative moment in favor of reflection, or perhaps what he calls celebration—the (non-relational) movement, as Hegel described it, from nothing to nothing?

In his embrace of sociology, Moten’s enters into a tradition stretching from Simmel, through Lukács, Adorno, and Habermas, that, as Gillian Rose has pointed out, is haunted by a problematic Kantian-esque construal of ‘the social’ as a value (Wert) in and for itself. By focusing instead on the production of subjective meanings that re-present actuality, sociology (aesthetic, Marxist or otherwise) suppresses the capacity to present actuality; lacking a concept of material contradictions (in law, media, or property relations), it forecloses upon the possibility of conceiving transformative social activity (see Rose 1981).

Moten seems mostly to sense the threat of a non-transfromative sociological pitfall, particularly in the final chapter of the book on Frantz Fanon. In contradistinction to Fanon’s “sociogeny,” the phenomenological tracing of development through social factors, Moten claims his “sociology” (taking after Du Bois) is explicitly about the “sociopoetic cognizance of the real presence of the people in and at their making, where that retrospective ascription of absence that Fanon’s inhabitation of the problematic of damnation…is given in and to a lyrical, analytic poetics of the process of revolutionary transubstantiation” (UM, 228). Sociology as analytic poetics, rather than social analysis full-stop, would seem somewhat to resolve Rose’s concerns about transformative (or transubstantive) activity, but perhaps by falling back on an aestheticized notion of political process (which has a problematic history of its own).

Moten’s discussion of Fanon here is a lightly amended version of his 2013 essay on Afro-pessimism. It groups together the most urgent concerns in the book, if not the series on the whole: the interrelation of ontology, (stolen) social life, and the resistance of the object. Beginning with Fanon’s project of “narrating the history of his own becoming-object,” Moten argues that Fanon disturbs the Heideggerian distinction between das Ding and Dasein. Moten, however, is “most interested in” the beings that are always escaping the ontological binary, who unsettle the very possibility of being accounted for. Moten, in other words, wants to argue for that the problem of the inadequacy of ontology to blackness is actually a problem about the inadequacy of “already given ontologies” (UM, 150). The lived, ontic, social life of blackness is, Moten argues, in constant demand for a different way of articulating being that lives in the impossibility of origins.

Moten’s capacious thinking in this final volume of his series—about foundations, origins, “the political,” Schmittian residues, the impossibility of political theory, and Heidegger’s legacy—also dovetails with recent trends in contemporary European political thought that I mentioned at the beginning of this essay. By way of conclusion, I consider how cntbsb provides powerful critique of some of those tendencies.

***

Despite the flurry of interest, there has been little consensus about what political ontology stands for. Its usage remains broad, having been applied to thinkers like Judith Butler and Charles Taylor alike; it can also appear in ‘strong’ or ‘weak’ forms depending on who you’re looking at. In an attempt to weld together some common traits, Marchart has argued that political ontology, at a metaphilosophical level, inquires after the “fundamental ontological presuppositions that inform political research and theory” (Marchart 2018). It appears, more particularly, when thinkers claim that politics has a structural analogy with Heidegger’s “ontological difference” between Being and beings (Sein and Seinendem).

Pace Carl Schmitt, thinkers like Jean-Luc Nancy, Alain Badiou, Ernesto Laclau, and Giorgio Agamben argue that there is a difference between ‘the political’ and ‘politics’ (le politique/une politique, das Politische/die Politik). Like Heidegger’s Sein, ‘the political’ is what is ineluctably given; it is marked by conflict, exclusion, or better yet by “antagonism” (the term Marchart prefers). Thus, any action against the given or ‘the political’, thinking included, constitutes a political intervention, and constitutes a political subject. In this regard, political ontology emphasizes the latent political nature of every social being.

In compendiums on political ontology, or in the work of theorists they describe, there has been no mention of a similar turn to political ontology in black studies, and its critical function in Afro-pessimism. When political ontology is said to have any relevance to ‘ontic’ matters it is usually, following Heidegger, linked ecological concerns only. How one can think antagonism without centering that concept around an analysis of race, gender, or class is a question that proponents of political ontology have yet to satisfyingly answer, and maybe one that they don’t want to get tied up in at all. One of the self-proclaimed advantages of political ontology is, apparently, that it can transcend the “relativism” and “identity politics” that have taken hold of leftist imaginary in recent years (Strathausen 2009).

Excepting its distaste for the ontic, Moten’s intervention illuminates yet another reason that we might want to be skeptical of political ontology. If Marchart is concerned with the ontological presuppositions that undergird political theory, Moten is concerned with the inverse. How does political theory, or ‘politics’, as a mode of thought concerned with regulating difference, antagonism, the production of an Other, give ontology its grounding? To re-appropriate Heidegger, how is ontology occasioned by a phenomenological refusal to understand Black being? If ontology cannot but move from its denial of world, perhaps its absorption into politics does nothing more than preserve the “officially assumed position.”

This is not to fully discount political ontology in either its continental or Afro-pessimisitic iterations. From Moten’s perspective, there is at least value there as a descriptive framework, as a way of illuminating projects of emancipation that fly by the official eye. But, must political theory – understood properly as: “the remains of hope” – be content to simply interpret the world? Political ontology stalls within the realm metatheoretical description, securing itself as tantamount to an emancipatory opening. Moten offers, on the other hand, a necessarily partial, unfinished conception of theory that can only be met on another side by aesthetics, by poetry, by praxis. For Moten, Marx’s old distinction between interpretation and change remains at play; political ontology clings glibly onto one side of the phrase.

Mimi Howard is a PhD candidate in Politics at the University of Cambridge, writing a dissertation on method and critique in 20th-century German political philosophy.

Acknowledgements

To our Lesekreis “Rehearsal” (Berlin), and to Merve Fejzula for her insightful thoughts and edits.

Works Cited (aside from reviewed work)

Agamben, Giorgio. 2017. The Omnibus Homo Sacer. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. 2009. “Capitalism: A Very Special Delirum.” In Chasosophy ed. Sylvere Lotringer. New York: Semiotexte.

———. “The Exhausted.” 1995. Trans. Anthony Uhlmann. SubStance 24. 3: 3-28.

Chandler, Nahum Dimitri. 2000. “Originary Displacement.” boundary 2 27.3: 249-286.

Fanon, Frantz. 1986. Black Skin, White Masks. Trans. Charles Lam Markmann. London: Pluto Press.

Heidegger, Martin. 1971. “…Poetically Man Dwells…” in Poetry, Language, Thought, trans. Albert Hofstadter. New York: Harper & Row.

———. 1987. Zur Bestimmung der Philosophie: Gesamtausgabe 56/57. Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann.

Marchart, Olivier. 2018. Thinking Antagonism: Political Ontology after Laclau. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

———. and Mihaela Mihai, Lois McNay, Aletta Norval, Vassilios Paipais, Sergei Prozorov, Mathias Thaler. 2017. “Democracy, critique and the ontological turn,” Contemporary Political Theory 16.4: 501-531.

Moten, Fred and Charles Henry Rowell. 2004. “’Words don’t go there’: An Interview with Fred Moten,” Callaloo 27.4: 954-966.

———. 2013a. “Blackness and Nothingness (Mysticism in the Flesh),” The South Atlantic Quarterly 112.4: 737–80.

———. and Stefano Harney. 2013b. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study. Brooklyn: Autonomedia.

Rose, Gillian. Hegel contra Sociology. 1981. London: Athlone.

Saar, Martin. 2012. “What is Political Ontology?” Krisis 1: 79-83.

Stahl, Titus. 2013. Immanente Kritik. Elemente einer Theorie sozialer Praktiken. Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag.

Strathausen, Carsten ed. 2009. A Leftist Ontology: Beyond Relativism and Identity Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Taylor, Paul C. 2013. “Bare Ontology and Social Death.” Philosophical Papers 42.3: 369-389.

Wilderson, Frank B. 2010. Red, White and Black. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Wright, Michelle W. 2015. Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

[1] “In the end, that’s probably all my writing is—dropping names and droppin’ things, like Betty Carter.” In Charles Henry Rowell and Fred Moten, “’Words don’t go there’: An Interview with Fred Moten,” Callaloo 27.4 (2004), 954-966.