Charles Bernstein is the author of Near/Miss and Pitch of Poetry, both from the University of Chicago Press. ROOF recently published The Course, a collaboration with Ted Greenwald. University of New Mexico Press is publishing a reprint L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E magazine, a volume of related letters, as well as the late 1970s collaboration Legend. He lives in Brooklyn.

-

Colin Dayan — Police Power & Can’t Breathe

by Colin Dayan

Police Power

When I grew up in Atlanta, the police were known as “the laws.” I grew up hearing about the “meat that takes directions from someone.” The laws were as terrifying and unknowable as evil spirits. They controlled and judged. I heard stories of the patrollers who could get you if you were found walking outside at night. But they could be anywhere. The laws. Driving down to Florida, you knew where not to stop, which gas station to avoid, when not to turn and look at a red light, how to get to where you were going.

Until I left the South, I never felt safe. And now that I’ve returned, I still see the men in trucks, driving down the street like they owned the world. They are smiling. It’s what my mother called “a shit-eating grin.” Some of my neighbors talk about what might happen after sunset. They’re not afraid of police. I keep quiet. I am afraid of them.

George Floyd is dead because Derek Chauvin killed him, in close collaboration with three of his police colleagues. Of this there is no doubt, and it will be confirmed as fact when they eventually go to trial and are convicted on charges that go little way to match even the illegality, to say nothing of the brutality and savagery, of their crimes. That will not be the end of the story, for they are white and Floyd was black. There will be propaganda from the policemen’s union. That has already begun, with the union leader spewing out bile designed to get his men off the hook. There will be appeals. The (now ex-) police officers will spend some time in prison. Then, on release, they will, given how these things work in the United States, find their way back into gainful employment. That will probably be in some form of policing. That is what happens in more than fifty percent of such cases; and this inevitability represents the racism and oppression based on color that structures this country.

What are the deeper and more structural aspects of this racism and oppression? No one, no American, no one armed with a big gun, no other American police officer except, just possibly, a direct superior of the four killers who was actually known to them, not the governor of the state, not even the president of the United States, could have stopped these police officers from killing George Floyd. Eight minutes is a long time, but it is short enough to kill a man, slowly. Physically intervening would have been dangerous, risking the life of anyone who tried. It is risky to get involved when a heavily armed gang of four killers is busy killing someone, and when those gang members are policemen it is even riskier.

That makes this particular killing sound like another anonymous murder in the druglands of Mexico, or the favelas of Brazil, or the excesses of the military dictatorships of Latin America before democracy returned, or the terror of Duterte’s Philippines. But while all those cases are painted bright in the colors of the American flag, this one is right here. And while all those cases represent extra-judicial, illegal forms of action, the case of Derek Chauvin represents legality at its worst.

Legally intervening to save George Floyd’s life was impossible. Interfering with the actions of a police officer in the United States is legally a crime. There might be cracks on this round the edges, but the central fact, all over the United States, is that you cannot interfere with a policeman killing a black man—executing his duties, as he sees them—without risk to your own life and limb and freedom.

The real story here is about police power and its effects on the lives of Americans, white as well as black, and the character of the United States as a country that tells itself—no less than the rest of the world—lies about what it is, what it stands for and how it stands for it.

The ghost of slavery is built into our legal language and holds our prison system in its grip. To the extent that slaves were allowed personalities before the law, they were regarded chiefly—almost solely—as potential criminals. During the second session of the 39th Congress (December 12, 1866-January 8, 1867) debates raged on the meaning of the exemption in the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. It abolished slavery “except as punishment of crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” The parenthetical expression guaranteed enclosure, a bracketing of servitude that revived slavery under cover of removing it. Those who were once slaves were now criminals, and forced labor in the form of the convict lease system ensured continued degradation. As Charles Sumner warned, the locale for enslavement would move from the auction block to the courts of the United States.

Can’t Breathe

This piece was originally published in Transition (2015) in the issue “New African Fiction”: “I Can’t Breathe,” included with other responses to the murders of unarmed black Americans by police.

Hard to write what I want to say. Knowing that my words can’t even get close to righteous response. I remember Birmingham and Jackson and being a child in Atlanta in 1963. What is happening now is different. It might be more pernicious, more lasting, less easy to combat. No Civil Rights Act can stop it. Trying to put into words what these murders of blacks—by any white person, police or not—tell us, I sense a desire to repeat the racial tags of our American history, a litany of law that seems like a series of death announcements that always precede and continue to haunt the bodies left lying on the street losing blood unable to breathe talked over and done in.

But instead I can only say what I keep thinking about: How the most well-intentioned and reasonable folks end up abetting the state of fear and atrocity, terrifying because commonplace—easily as tactful as de Blasio’s call “for everyone to put aside political debates, put aside protests, put aside all of the things that we will talk about in due time.”

I remember Nina Simone’s words in “Mississippi Goddam,” “Keep on saying ‘go slow.’ ” Who has to slow down? How long is due time? Real terror plucks us by the sleeve and comes along naturally, forever just occurring, always perceptible just at the edge of our vision. What terrorizes is this casual but calculated disregard. A terror relayed not by

the dogs, hoses, and bombs in the new South of the sixties, but by the near nonchalance of legal murder anywhere in the United States today: as if these living breathing black citizens, now dead, were not supposed to go about their lives, walk down the street, stand on a corner, put their hands in their pockets, take a toy gun to the park, go down the stairway of their own building—breathe.Colin Dayan is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences as well as Robert Penn Warren Professor in the Humanities at Vanderbilt University. She has held Guggenheim as well as other distinguished fellowships.

-

Anthony Bogues — Black Lives Matter and the Moment of the Now

by Anthony Bogues

We live in an extraordinary moment. One in which many cross currents tussle for sustained dominance. A moment when armed white supremacy groups make attempts to take over state legislative offices in states like Michigan. One in which the science of contagion is in battle with a myopic individualism in which the wearing of a mask for medical protection becomes a signifier for a political symbolic battle around hegemony. All of this occurs in a moment when there is a historic pandemic, one which should make us as human species reflect on our contemporary ways of life. A pandemic which exposed the structures of the American health system where race and class determine those who will survive and live and those who disproportionately die. In the midst of this crisis, in which lockdowns and shelter in place were every day practices, we witnessed one of the most significant global protests that the world has seen for some time. The protests upended many commentators, shattered many conventional wisdoms about politics and at least for a time punctured the everyday normal many of us had become accustomed to. So what was at the root of this upsurge? And what are its significances? And, therefore, how might we understand it?

In the epigraph to the first chapter of Black Reconstruction (1935), WEB Du Bois writes about “How black men, coming to America … became a central thread to the history of the United States, at once a challenge to its democracy and always an important part of its economic history and social development.” That challenge has historically been the touchstone for both American democracy and its civilization. Racial slavery was a cornerstone of capitalism. It is not that racial slavery laid the foundation for capitalism; rather racial slavery, the plantation slave economy, the African slave trade were themselves practices of capitalism. At the core of the inauguration of capitalism was not the factory system with its wage labor but the slave plantation, unfree labor and a network of credit and debt arrangements. In Debt: The First 5000 years (2011), David Graeber points out how the Atlantic slave trade depended upon a system of debts and credits. Within this system emerged various institutions we now associate with capitalism from bond markets to brokerage houses. There was also the emergence of major companies whose chief functions were linked to slave trade, financing plantations and other aspects of the European colonial project. Here one can refer amongst others to the Dutch West India Company, the French Société de Guinée, and of course, the Royal African Company of England. At the core of what historian Catherine Hall calls this “slavery business” was the African captive who became an enslaved person. The late African American theorist Cedric Robinson called this historical process “racial capitalism.”

The enslaved body as the Caribbean historian Elsa Goveia said was “property in person.” It was a body that produced commodities while it was commodified. The black female enslaved body reproduced this commodification process three times over, as a body producing commodity, while being a commodity and then through sexual violence a reproductive body of enslaved labor. The plantation was a site of generative violence of commodification. Capitalism was inaugurated through the various violences enacted upon the enslaved black body. Exploitation was established upon the foundation of unfree labor. That is the history of capitalism: not a stages theory of transition of societies from one mode of production to another, but rather a historical process of generative violence upon the bodies of the African enslaved. In such a history the body is not secondary, it is the source of the methods, the several ways, of practices which turn the human into an enslaved dehumanized thing. Creating such a historical process, the colonial and planter power needed to construct forms of life, ways of thinking, construct modes of being human that would at least for a time guarantee the full reproduction of a society. To put this another way: exploitation requires forms of domination and the latter requires ideas and practices which the dominant elite and others accepts. This is about the manufacturing of what Gramsci calls “commonsense,” a kind of naturalized underpinning of a society, an ideational glue which holds society together. In slave and colonial societies violence was regularized as a technique of rule because in such societies might was right. And while this was so these orders also ruled by a set of ideas and practices about who was human and who was not.

All nations we know are an “imagined community” and as such we search for what glues bind the nation together. In America, the glue that has bounded the society together is not the fiction of America as an idea, the exception of the “City on the Hill,” rather it has been anti-black racism. What Du Bois calls the “wages of whiteness” became the naturalized commonsense which structured the everyday practices of living. Anti-black racism, has a long history founded within the matrices of the generative violence of the African slave trade; elaborated in plantation slavery through a complex system of customs and legal codes. It was codified in human systems of classification promulgated by European natural historians in the 17th century, mapped by Christian doctrine whereby some human beings had souls and some not; and then, in the 19th century, recodified through the so-called scientific studies of skulls–phrenology–a pseudo-science of the study of the mind in which it was said that Africans were inferior because of the size of their skulls since the brain was located in the skull. And when science made it clear that there was no scientific basis for anti-black racism then culture became a terrain to explain the supposed inferiority of blackness.

So blackness as visual marker produces within the dominant commonsense the death of the black person. Black life becomes disposable, is a lack, has no interiority, it is locked upon itself. As a visual marker, the black body has no escape. Its public presence is an affront, it must be tamed, put back in its place. It must be not allowed to breathe, because breath is life and for the black body to breathe means it has life. This is not primarily an American phenomenon. The history of racial slavery in America, the inauguration of Jim Crow and formal segregation, given the imperial power of America on the world stage created the illusion that there was a special American race problem. Of course, all societies have their own historical specificities, but anti-black racism was not an American feature alone. What Du Bois called the “color line” was embedded in the world because racial slavery and colonialism were parts of a global system which ruled much of the world from the 15th century Columbian voyages onwards. The anti-black racism of European colonial powers drew from racial theories created in America, the Caribbean, the historical encounters between Europe and Africa. South African apartheid drew some of its resources from the structures and practices of American Jim Crow. In all this the black body was the disposable surplus; not the other but the irremediable non-other, that which could not be fully included into the body politic of the given nation. Such an irremediable body, always on the outside, challenges the very meaning of democracy itself. It is why struggles around anti-black racism shake the society, indeed call Western civilization into question.

If we agree historically that the foundation of the capitalist West was racial slavery and colonialism and the accompanying genocide and attempted genocide of the indigenous populations, then what we are witnessing today are the challenges to this foundation. Capitalism is not just an abstract economic system as Marx made clear long ago when he noted that economic relationships are always between people. To rule, to be able to reproduce itself, any social system creates ways of living, modes of being human as it is then understood. Historically and in the present, anti-black racism and the creation of whiteness, of white supremacy was both a way of life and a signifier of being human. It is not just an ideological belief but rather a naturalized commonsense which in many ways functions like a fantasy, one which has material life and consequences. Commonsense as well in part is constructed by the historical understandings of a society about itself. We are, as humans, historical beings that make sense of ourselves through memories of the past. We take from that past to make the self. In societies where the past has been a historical catastrophe, where regularized violence operated as “power in the flesh” making the “human superfluous,” that past becomes a critical way to establish the grounds for inhumane ways of life. America’s unwillingness to confront the fact that it was a slave society since its founding as a British colony; that practices of settler colonialism wreaked havoc on the indigenous population; Europe’s unwillingness to confront its own history as multiple colonial powers now provides a dominant commonsense which structures the present. Yet as the poet and thinker Aimé Césaire noted in 1955: “Between the colonizer and the colonized there is room only for forced labor, intimidation, pressure, the police, taxation, theft, rape, compulsory crops … no human contact, but relations of domination and submission.” This history is elided by European countries. It is a history made visible through the various pacification campaigns, the genocide of the Herero people in Namibia and regular cutting off of the hands of the Congolese people. A history codified through forms of rule which created the African subject into a native and turned various African social and political formations into tribes. However, history lives in the present and becomes memorialized into the public landscapes of monuments. Monuments are an encoded system of public signs which enact meanings in the public domain. So when the Black Lives Matter Movement and those activated by it demand the removal of monuments, they are engaged in a move of symbolic insurgency to get rid of the public landscapes of the everyday historical monumentalization in the present. This happens in America, in South Africa, the UK. And continental Europe cannot escape the fire this time.

So here we are. For over a month there has been in America the single largest protests in America’s history. These protests were ignited by the public lynching of George Floyd who cried out “I can’t breathe,” before being murdered and then died with the words “Mama” on his lips. In that modern lynching scene, for nearly 9 minutes we witnessed the meaning of anti-black racism. Yes, it was the police man who kneeled down on his back and neck. Yes, the American police force were operating like modern day slave catchers. But there was something else and that something else was the casual nonchalance, the non-recognition that Floyd was human. It was the nonchalance that Floyd was just another disposable black body. The daily confrontation between black men and increasingly black women with the police is the nodal point where anti-black racism is most visible. In this nodal point there is no pretense. State authority expresses itself, that might be right, that black life does not matter. This is so in Brazil, in parts of Europe, the Caribbean, America or indeed in parts of Africa. Here ordinary black life does not matter.

After the death of Trayvon Martin, in 2013, a group of black feminists, Patrisse Khan-Cullors, Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi, formed the organization which became known as “Black Lives Matter.” Today the name of the organization has become a political banner igniting the political imagination of both black and white around the world. There is a rich historical current in which black revolts / uprisings have catalyzed various struggles around the world. In the 19th century the dual Haitian revolution inspired Greek anti-colonial figures fighting against the Ottoman Empire when some of them wrote to the Haitian government requesting arms and political support. We recall how what was then called “Negro Revolt”, the black uprisings in the 1960’s, influenced feminist and the anti-war movements around the world. In all this the African American spiritual “We shall overcome” became a clarion political message of many movements. So why, might we ask, does Black Lives Matter at this moment become transformed into a catalytic political banner, one which has engaged the political imagination of thousands? I return to Du Bois.

Racial slavery was the foundation of America and, I would argue, of the making of the modern world. As a form of domination its very core was the double and triple commodification process I addressed earlier. It was about making non-human another human being. As a generative historical process, it lasted for centuries. That is a special form of domination which not only required violence but creating another kind of human being, one who would be surplus and disposable. It also created the conditions for Black struggle to be catalytic, a point the Caribbean historian and radical thinker CLR James made in 1948, when living underground in the USA in the 1940’s he noted in a seminal essay “The Revolutionary Answer to the Negro Problem in the United States that “this independent Negro Movement is able to intervene with terrific force upon the general social and political life of the nation.” Black Lives Matter became a political banner because it challenges continued racial domination, its deep rooted legacies and consequences. It says we are human. It demands that as human the society should be transformed to create new ways of living. It not only therefore exposes police brutality but calls to order the entire historical foundation on which Western civilization rests, which is why getting rid of the historical monuments which venerate the West has become so crucial. While being part of a historic black liberation tradition, BLM political organizational methods have enacted critiques about Black masculinity. Given all this, Black Lives Matter as a political banner is world historic. And here the reader might pause and wonder why? Let us return to the making of the modern world; to the ways in which anti-black racism continues in the after-lives of racial slavery to dominate black life and has done so for centuries. So when there are sustained protests against the institutional and everyday forms of anti- black racism and this happens on the global stage. Is this not world historic? The current global protests are world historic because they confront the entire panoply and edifice that built the modern world. They are also world historic because they posit different methods of political organizing which breaks from previous forms of radical black movements. When the movement demands that monuments which invoke the past that undergirds the present must fall, it draws from the earlier struggles of South African students and the Rhodes Must Fall Movement. It demands abolition, making the word capacious, creating a new political language not just about abolishing prisons but demanding the opening of a new space, invoking the radical imagination to think of new ways of life. If many social and political radical movements have paid attention only to the state and the economy as structures of the present, Black Lives Matter is attentive to the history of the structures and their underlying assumptions and commonsense.

We are indeed in a new moment. Some say this moment feels different in part because the world wide protests have been multiracial, as the image of a lone white woman sitting on the sidewalk in a rural American town with a sign which reads “Black Lives Matter” illuminates. But perhaps what is most different about this moment is that for the first time in a world governed by neoliberalism, one in which as Stuart Hall and Alan O’ Shea put it, there is a neo-liberal commonsense, we are witnessing an uprising which challenges a foundational element of that commonsense. A commonsense in which anti-black racism has been a glue for the American body politic. This is an uprising of the radical imagination which demands abolishing the reproductive structures of the making of the modern world. However, as Stuart Hall makes clear in his work, commonsense is a contested terrain, In every major uprising where elements of the dominant order have been challenged, power when it cannot defeat immediately or ignore the uprising attempts to coopt, to integrate signs and symbols of the upsurge into the dominant thereby gutting them. So the response of many American corporations has been to proclaim support for Black Lives Matter, not the movement but to appropriate the banner turning it into a slogan. So when Amazon proclaimed on its website at the height of the protests that Black Lives Matter it was responding to a popular upsurge it could not ignore. Amazon’s practice was one of appropriation. One of the remarkable features of American power is its ability to quickly gobble up what begins outside of the body politic and then rework it into a hegemony without fundamental changes occurring. This is one aspect of the present moment.

We end where we began, with Du Bois and Black Reconstruction.

In 1935, Du Bois identified in Black Reconstruction a form of politics he called “abolition democracy.” It was, he argued, the necessary radical political framework if the transformation of America was going to occur after the civil war. For Du Bois, “abolition democracy” in his words “pushed towards the dictatorship of Labor”. By then Du Bois in the most radical phase of his intellectual / activist life. Eighty-five years later the black radical imagination has reworked abolition into a demand for new ways of life dismantling the structures which inaugurated the modern world. Fundamental change may not come and at the time of writing this piece, things can be said to be in flux and for sure a revolution is not around the corner. But historically, fundamental change requires the work of the radical imagination, the thinking that a new form of human life is possible. The global Black Lives Matter protests have opened that space. That is its remarkable significance for the current moment.

Anthony Bogues is Asa Messer Professor of Humanities at Brown university where he is the inaugural director of the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice. He is also a curator.

-

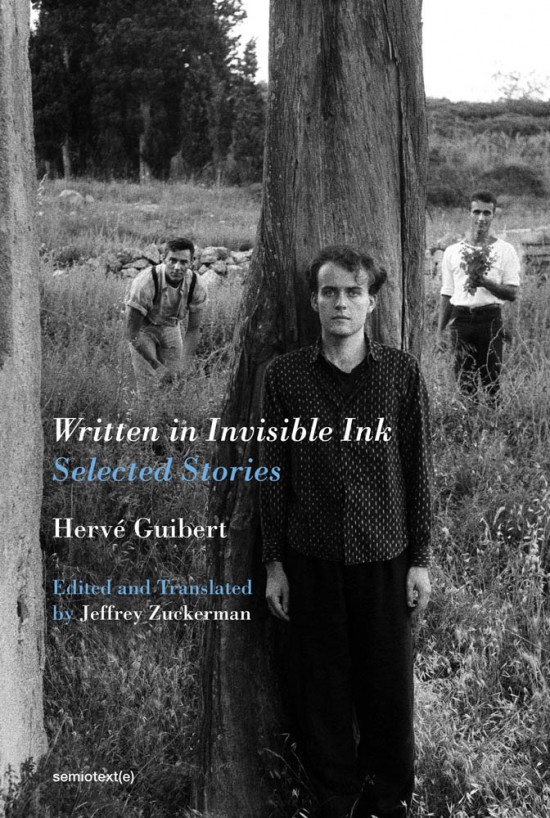

Peter Valente — The Body’s Prehistories (Review of Hervé Guibert’s Written in Invisible Ink)

The Body’s Prehistories: On Hervé Guibert’s Written in Invisible Ink

by Peter Valente

One of the many pleasures of reading Hervé Guibert’s collection of stories, Written in Invisible Ink (Semiotext(e), 2020), is following his development as a writer from the earliest stories in this volume, which date from the late 1970s, to the latest (which were collected in 1988’s Mauve Virgin). According to his widow Christine Guibert, he did not write any stories after 1988 and focused more on longer works such as the novel To The Friend Who Did Not Save My Life (1990).[1] Several of the stories published in this present volume have never been published before. Interestingly, the ones collected here, chosen by the translator Jeffrey Zuckerman, coincide with Guibert’s time as a journalist; many of the texts have the journalist’s attention for details that will capture a reader’s attention.

The stylistic difference between Propaganda Death, the earliest of his books, and the later stories is between the raw passionate writing of the former and the more controlled prose of the latter. Guibert was one of first French writers of “autofiction,”: he used writing from his diary as well as memoir and fiction to complicate the narrative “I.” The writing in Propaganda Death is almost cinematic in its cataloguing of physical violence to the body mixed with an unbridled sexual urge: “My body, due to the effects of lust and pain, has entered a state of theatricality, of climax, that I would like to reproduce in any manner possible: by photo, by video, by audio recording” (27). Its scenes of the savage torturing and disemboweling of the human body, amidst slaughterhouses and hospitals, exhibit the frightening transparency of what lies beneath the skin, revealing its secrets: “no need for candles to brighten this night of the body; its internal transparency illuminates all” (27). In “Final Outrages” Guibert imagines himself as the young girl Ophelia, “stolen away in the bloom of youth by an ailment gnawing slowly at her interior (while making her exterior radiate!)” (81). In “Five Marble Tables”, he writes, imagining himself dead: “I won’t let go of my body, I cling to it, I push out everything I can inside but it all stops immediately, I’m clean forever now, my muscles tear apart, I can’t go back in myself anymore and I leave this deserted place, all the fight gone, all the fury slain” (70). Death in life is imagined as transformative; in a later work, Crazy for Vincent (Semiotext(e), 2017), published in 1989, a year after the latest stories in this volume, Guibert writes: “I struggle with the mystery of the violence of this love…and I tell myself that I would like to describe it with the solemnity of the sacred, as if it were one of the great religious mysteries…I don’t have too many sexual thoughts, of fucking or of defilement, violent hallucinations that would bring sex or lechery into play, but rather the suspended grace of bearing witness to a transfiguration” (85). The thrust of these stories is away from materiality, and toward a refiguring of the male body as a site for spiritual transformation.[2]

Propaganda Death is also an ecstatic fantasy of destruction, desecration, and horror, calling for nothing less than the annihilation of the petit-bourgeois world through a complete reversal of cherished mores and customs, and its obsession with good hygiene, both physical and mental: “I’d like to smear my gonorrhea over the entire world, infect the planet, contaminate dozens of asses at a go, …my bed every morning is a field of carnage, a slaughterhouse” (51). He continues: “Let’s open abscesses in all this stupid flesh!…Let’s love ourselves and hate them! Let’s orgasm as we pull our heads from our bodies!” (47). Wayne Koestenbaum writes:

Filth is Guibert’s passport to infinity. Filth, as literary terrain, belongs to de Sade, but Guibert reroutes s/m through the pastoral landscape of religious interiority, as if ghosted by hungry Simone Weil, or by Wilde’s scarified, Christological denouement. (To skeptics, such spirituality might seem papier-mâché, but I’m a believer.) Guibert sees a cute young man at a party and “instead of imagining his sex or his torso or the taste of his tongue, in spite of myself it’s his excrement I see, inside his intestines.” (Kostenbaum 2020)[3]

These passionate, anarchic early texts are difficult to read. They are unpolished, raw, unedited, obsessed with the violence of desire, and with orifices; but nevertheless, they are works of great intensity, written when Guibert was 21 years old, and likely to shock a reader into a recognition of his/her own body, and its impermanence, and the weakness of the flesh. They are performance, spectacle, and indeed, propaganda in defense of homosexuality and the violence of desire.

Guibert seeks to “to uncover my body’s prehistories,” the traces of the animal inside the human. In the story, “Flash Paper,” he writes that while kissing Fernand, he imagines that “Out of the extended, warm pleasure of the kiss came other visions: we were two animals that had met on the terreplein, each from our own half of the forest, two horned beasts, two giant snails, two unhappy hermaphrodites” (Invisible Ink 230-31). And, continuing with this theme in the same story: “His wide-opened eye had awakened mine and did not leave it: we had become insects” (232). He and Fernand are, “two poor shameful animals” (233). Finally, he writes: “we danced like two spider crabs being boiled, destroying everything in their path” (234). The erotic charge of an encounter turns men into animals searching for their release. There is danger and excitement in the kill, the sexual energy of it: “If I fuck him, if I decide to fuck him, it’s first to annihilate him.”[4] This is “no simple sadism…no simple equation of fucking and killing, of penetrating and violating – instead, the wish to fuck or be fucked…is a sensation of being voided, chiseled, scalded, disemboweled. Is this consciousness a queer privilege? Is it shamanistic? Is it in fact not trans or queer or anything of the sort, but simply poetic?” (Kostenbaum 2014). Guibert could certainly be melodramatic, as well as poetic. Sex in his work is theatrical; he plays a game of hide and seek with a reader; but he doesn’t sugar coat desires that are complex or grotesque and this is what makes his work so valuable as a document of honest writing in a time such as ours when the line between truth and falsity has been blurred.

In the section, “Personal Effects” Guibert examines objects rather than bodies and reveals their hidden meanings or forbidden histories. About the “Cat o’Nine Tails”, for instance, he writes: “The cat o’ nine tails has been hung, among the cobwebs dusters, from ceiling hooks, in the dim backroom of the hardware store. It carries within itself, in its unmoving straps, the screams of battered children, it exhales the pleasure of perverted lovers” (Invisible Ink 97). Gloves are a normal part of winter wear or when working in the garden, or in construction et cetera, but Guibert reminds us that “it should never be forgotten that the hands they’re keenest to help are those of thieves and stranglers” (103). With regard to the “vibrating chair,” he notes that the dukes of Pomerania found “extravagant” uses for it, including attaching a large dildo to its seat (107). This section of the book is representative of Guibert’s poetics. As a journalist, he was accustomed to examining the forbidden histories behind things which elude the eye of the observer. In “Newspaper Clipping,” he talks about certain facts concerning the death of a person and cautions about imaginatively reconstructing the scene. “Let’s come back to reality!,” he writes, concluding that “…everything, for now, remains purely hypothetical” (56). The secret will not reveal itself easily and it requires patient and research to reveal a truth perhaps stranger than fiction.

In the world of these stories, love is essentially a complex power game, where the weak person is always at a disadvantage. Guibert is not a psychological writer, concerned with exploring in depth the subjective feelings of lovers. There is no utopian idea about love in these stories. Love is often deceptive, leading to betrayals and even violence. “For P. Dedication in Invisible Ink,” concerns a young writer who has complex desires toward an older, more established writer, and is called upon to help him write a book. At the end of the story, the young writer speaks of their erotic dynamic in the following way:

The king of the jungle had been tamed, or maybe it was the lion that subdued its tamer, but one or the other, at his point of submission, attacked the other in hopes of breaking him, and these visits grew increasingly rare. The break-up happened over the course of the seventh year, bit by bit, as if by blows, and neither the assailant nor the stronghold, at risk of breaking their necks, wanted to bow down. (159)

Love often begins with a kind of “tacit contract” that one or the other eventually betrays. In one of the central stories, “The Sting of Love,” love is imagined as a liquid that is injected in the lover. The story traces its various effects on those who have been “infected” and concludes:

A happiness so great becomes unbearable unless one is shackled, or better yet, in bed, because the effect of this injected liquid doesn’t end with any climax, it persists all the way into sleep. It is impossible here to determine the specific link between consciousness and dreams. Anyone who wants to fight against this surreptitious transition with conscious effort, who is afraid because the dream, at first still just as wholly gentle, slowly turns into nightmare, flickering with swift animal shapes, anyone who wants to prolong this amorous stupor indefinitely with a second injection is struck with melancholy, as with a tarantula’s bite, and loses speech, nails, job. (135)

Physical attraction is just as capricious and mysterious and not necessarily the result of erotic language: “We sat facing each other in the small, unlit kitchen, and I immediately felt within his physical presence a sense of elevation, adventure, freedom. The words he had said had nothing overtly erotic about them, but they suddenly, mysteriously had my penis swelling” (182). There is no attempt to seek a reason for his desire which would amount to a kind of defense; Guibert was open about his homosexuality and its relation to danger as well as pleasure. Furthermore, this physical excitement can suddenly turn into potential violence: “two years earlier, walking behind him, I had suddenly wanted to use all my force to hit the back of his neck with the heft of the camera hanging by a strap around my wrist” (178). In “For P. Dedication in Invisible Ink”, Guibert writes, “My feelings about this man were skewed: even as I could have said that I loved him, when I found myself before him, at long last, I wanted to go for his throat” (153).

Danger extends to sexual encounters in the park. In “A Lover’s Brief Journal,” Guibert relates an incident in the Tuileries, where, after “a guy whispers the word cop,” he and another man get dressed, and leave the park; but Guibert is then assaulted: “the first one punches me in the face, another kicks me in the balls, right after a third guy takes a running start to headbutt me, I fall down, I get back up, I shout for help without thinking about it, they run off, I run in the other direction, I turn around, I see one of them hurrying to pick up the coins that fell out of my pocket, hungry, greedy” (48-49). The violence has as much to do with money as with sexuality: the link here is between capitalist greed and homophobia. Though capitalism created the material conditions so that both men and women could lead independent sexual lives, it also, at the same time, imposed heterosexual norms on society to create an economic, ideological, and sexual regime, centered in the family. In the present time, when Trump, a symbol of capitalist greed, is seen as a spokesman for the white, heterosexual male, and encourages violence against marginalized groups on the basis of their skin color, religion or sexual preference, it is no surprise that we see a rise in violence against gay and trans men and women.

For the narrator of “Flash Paper,” love is, “ a voluntary obsession, an unsure decision” (239). But Guibert writes of the man who died in “A Man’s Secrets,” “All the strongholds had collapsed, except for the one protecting love: it left an unchangeable smile on his lips, when exhaustion closed his eyes” (254). And the aging star in “The Desire to Imitate” says, “In this impossibility of love there will have been all the same a little love” (212). In these stories, love and cruelty are woven together; this unholy union was born of Guibert’s hatred of his own body, his self-pity, his anger, his theatricality, his passion for the grotesque. He is attacking bourgeoise values, and inherited ideas about morality, thus turning our assumptions about love and hate upside down. Men who knew him said he was cruel but he hated pity and charity; Marie Darrieussecq writes that he preferred real friendship and despised cowardly people (“Guibert’s Ghost” 2015). For Guibert, true love may be impossible, but all the same, he valued the love that was possible in genuine friendships. He sought the truth in himself by testing the limits of his body and of his desires. In a world where our freedoms are being assaulted by both far right conservatives and neoliberals, a writer like Guibert is necessary and should be read, because he questions our conventional ideas about the nature of sexuality, love and hate.

Death hovers on the periphery of the stories in Written in Invisible Ink, and is often a central theme, and linked mysteriously with desire. In “Five Marble Tables,” Guibert imagines himself on a laboratory table, communing with other bodies, one of which is a young child. As I suggested earlier on, in the story Guibert feels in some way liberated: “I’m clean forever” (Invisible Ink 70). Guibert speaks of the dream, a kind of death-state in itself, as concealing, “a geography of pleasure, an itinerary with its impasses, its openings, its stairwells, its gulfs, its forbidden directions. Desire is there alone, idealized, freed of all materiality” (75). It can also contain, “desirable monsters,” such as the man whose “suffering was immense” because his “head is four times larger than his body” (129) and who believes the hand that gives him his food through a trapdoor is the hand of God. The monstrous, the forbidden, is a gateway to the spiritual.

In this palace of desirable monsters are men with “dog’s or wolf’s heads” or with “scales or moss growing on their skin” (129, 128). The animal and the vegetal are mixed and the monstrous appears beautiful. A world based on reason, a human creation, gives over to the animal, the irrational, the monstrous. This space contains an alternate time that exists simultaneously with the real world. In “Posthumous Novel,” one of my favorite stories, Guibert writes of a space where, as a result of a “deatomization effort” in Holland, “countless words, incomplete sentences” are “hanging like clumps off of trees and, broken and sown over the ground” (143). Words are not necessarily attached to sentences but exist alone as fragments. In the story, Guibert writes that when one is travelling by train, one’s thoughts release, “more or less clouded and blinded” words into the air of the surrounding countryside and that they take root in the “roadside dust, a branch shaken by the wind, setting sun” (144). These words or sentences, cast into the world by the living, are “nourishment for the dead…a vital message of what happens in the hereafter” (144). By accessing these “sentences” through “x-raying” the “final trajectories” of the young writer in the story who committed suicide, the author is able to partly reconstruct the dead man’s novel (146). The narrator is like Orpheus, in Cocteau’s film, listening to the transmissions on the radio which are actually the voices of the dead. These words of the dead need to be remembered. History must be remembered in order not to repeat the same mistakes to the point of unconsciousness.

It is in this forbidden space, this underworld that does not obey the laws of physics, that Guibert, a kind of Orphic figure, is able to imagine a language that is not bound to its materiality; it exists in the air, unrealized, incipient, spiritual, the image of a ghost. It is here where the monstrous, the aborted, the abject thoughts reside, and where the dead dwell. It is a land that “had never been described or transcribed on a map” (220). It is a forbidden and magical place, where one has the “courage to be oneself, to present oneself, and to liberate every secret, to invent them” (150). Guibert wrote this book in “invisible ink,” from that place, as if the stories themselves are only the visible traces of what lies behind them: the sexual encounters that produced them.[5]

In January, 1988, Guibert was diagnosed with AIDS. As a result, he immediately found himself the focus of media attention and appeared on numerous talk shows. Early in his career, Guibert was openly gay and unashamed of his homosexuality and this, according to his translator Jeffrey Zuckerman, “was not meant as a provocation” but as “a quietly revolutionary stance in line with his particular brand of rebelliousness, in which, to quote a line from the end of “Ghost Image,” ‘secrets have to circulate” (“Translator’s Preface”13). Furthermore, Zuckerman writes, “When I began this project, all of Guibert’s translated novels were out of print – even To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life. At the time, it felt symbolic yet saddening: if gay rights were moving so steadily forward toward equality with the broader population, why preserve this particular, liminal past? Indeed, such an unprecedented nationwide – and even global – sea change in attitudes toward gay marriage and adoption risked effacing the long struggle that came before it, from Oscar Wilde’s trials and Alan Turing’s cyanide-laced apple to the Stonewall riots and the ACT-UP movement” (“Translator’s Preface” 15). And for this reason, the stories in Written in Invisible Ink are a valuable addition to Guibert’s work in English, and a good starting point for the reader unfamiliar with his work.

Peter Valente is the author of A Boy Asleep Under the Sun: Versions of Sandro Penna (Punctum Books 2014), which was nominated for a Lambda award, The Artaud Variations (Spuyten Duyvil 2014), Let the Games Begin: Five Roman Writers (Talisman House 2015) and Catullus Versions (Spuyten Duyvil 2017). He has also published translations from the Italian, Blackout by Nanni Balestrini (Commune Editions 2017) and Whatever the Name by Pierre Lepori (Spuyten Duyvil 2017), Two Novellas: Parthenogenesis & Plague in the Imperial City (Spuyten Duyvil, 2017). He is the co-translator of the chapbook Selected Late Letters of Antonin Artaud, 1945-1947 (Portable Press at Yo-Yo Labs,2014), and has translated the work of Gérard de Nerval, Cesare Viviani, and Pier Paolo Pasolini. His poems, essays, and photographs have appeared or are forthcoming in journals such as Mirage #4/Periodical, First Intensity, Aufgabe, Talisman, Oyster Boy Review, spoKe, and Animal Shelter. His most recent book is a co-translation of Succubations and Incubations: The Selected Letters of Antonin Artaud (1945-1947). Forthcoming is a collection of essays, Essays on the Peripheries (Punctum 2020) and his translation of Guillaume Dustan’s Nicolas Pages (Semiotext(e) 2021).

Works Cited

Darrieussecq, Marie. “Guibert’s Ghost.” Tin House, 13 January, 2015: https://tinhouse.com/guiberts-ghost/

Guibert, Hervé . 2020. Written in Invisible Ink. trans. Jeffrey Zuckerman. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

—- 2017. Crazy for Vincent. trans Christine Pichini. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Kostenbaum, Wayne. “The Pleasures of the Text.” Book Forum, June-August, 2014: https://www.bookforum.com/print/2102/herve-guibert-s-unbridled-eroticism-13298

Zuckerman, Jeffrey. “Translator’s Preface” in Written in Invisible Ink. trans. Jeffrey Zuckerman. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2020, 1-15.

Notes

[1] Guibert married Christine in 1989, so that she could protect his estate and so that the royalty from the sale of his books would go to her children. The publication of the mentioned novel, in which Guibert told the world he had AIDS, caused a scandal because in it he disguised Michel Foucault, who had the same disease, under another name (Muzil). However, the public discovered that this was Foucault; he had been dead for six years (reportedly from cancer) at the time of the publication of Guibert’s book.

[2] For Bataille, the indulgence in “perversity” also contained a strong drive for the metaphysical, for that which lies beyond the body.

[3] I would also add Artaud to the list above in his researches into “fecality.”

[4]Quoted in Kostenbaum, The Pleasures of the Text,” accessed on May 17, 2020, https://www.bookforum.com/print/2102/herve-guibert-s-unbridled-eroticism-13298

[5] In “A Lover’s Brief Journal,” Guibert writes, “I got completely undressed, I write and that gets me hard, I jerk myself off with one hand…” Hervé Guibert, Written in Invisible Ink, 49.

-

Mikkel Krause Frantzen — Has Capitalism Become Psychologically Unsustainable? Six Tentative Theses on COVID-19 and Mental Health

This essay is a part of the COVID-19 dossier, edited by Arne De Boever.

by Mikkel Krause Frantzen

1/ The future is already lost, the loss is just unevenly distributed. This altered version of sci-fi author William Gibson’s famous one-liner captures our age nicely: there is, on the one hand, the permeating sense that the future has no future, that the future has slipped away before our eyes. On the other, this doesn’t mean ‘we’ are all in the same proverbial boat, that ‘we’ are suffering in the same way. It is also important to realize that this loss of futurity is not an abstract loss. When you are in debt and have pawned away your future, more precisely your future labor, in order to pay back a debt that can never be paid, it is not abstract. When you live in the Arctic and the ice is melting due to global warming and you can foresee that you cannot sustain your way of life, or you live in Australia and endless draught has made it impossible keep living on the land that you and your family have lived on for generations, it is not abstract. The loss is concrete and it has economic and ecological implications. To quote from Joshua Clover’s poetry collection Red Epic, “because reasons”: because capitalism and its genocidal and ecocidal machine.

2/ It wasn’t depression, it was capitalism. As I have written elsewhere (in the book Going Nowhere, Slow and also in The Los Angeles Review of Books), the loss of futurity is one of the symptom(s) of depression, if not its primary symptom. Since the 1970s, depression has gradually become the paradigmatic psychopathology of capitalist societies. Alan Horwitz has detailed how by 1975, the 18 million diagnoses of depression had surpassed the 13 million diagnoses of anxiety, and in 1980 the third edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) saw the light of day, a pivotal event within the field of psychiatry: “Although biological psychiatry and its central vehicle of depression were gaining ground during the 1970s, the implementation of the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-III), which the APA issued in 1980, was the central turning point leading to the transition from anxiety to depression.” That the history and rise of depression runs parallel with the history and rise of neoliberalism should cause us no surprise. When no such thing as society exists, when all forms of collectivity have been utterly destroyed, all there is left is the individual. If you are depressed, it is your own fault. Like in the diagnostic manuals, no context is needed. If you feel like shit, you alone are to blame. It is your own personal problem and responsibility.

3/ Capitalism kills love, but it kills more than that. There is an artwork by the artist duo Claire Fontaine, whose work often engages the relation between depression and the political economy: it’s a neon sign that says “Capitalism kills love.” But capitalism kills more than that. Capitalism, some times in the guise of neoliberal austerity measures, forces people to kill themselves. The examples are legion: Dimitris Christoulas in Greece, who put a gun to his head in front of the Greek parliament, declaring “I am not committing suicide, they are killing me”; Jerome Rodgers in England, who died by suicide aged twenty after two unpaid £65 fines spiraled to over £1000; Daniel Desnoyers in the US, who “committed suicide after he lost his insurance and access to his psychiatric medication because he was $20 short on the monthly premium.” Or a 22-year-old-student in Lyon, France, who set himself on fire in front of a university restaurant due to financial difficulties and a desperate, precarious situation. Quickly the hashtag “#laprécaritétue” spread: Insecurity, precarity, kills. Let’s also not forget the waves of suicides at the Foxconn factory in China around 2010, with one worker, Xu (not to be confused with the poet Xu Lizhi who killed himself at this exact place in 2013) telling The Guardian some years later: “It wouldn’t be Foxconn without people dying […] Every year people kill themselves. They take it as a normal thing.” This is capitalist normality: Suicide, death. You die before you should have, it’s a normal thing. All of this to say that the current crisis, or crises, is also a mental health crisis. Across the globe people (students, workers, the unemployed) seem to be getting more and more unhappy, desperate and depressed. It is a common, yet uneven condition. Some tragic cases (like those just described) make it into the news; many others do not.

4/ What COVID-19 intensifies is an already generalized condition. And then COVID-19 happened. At the time of this writing, the virus has led to more than half a million dead across the globe. Since the outbreak of the pandemic 40 million Americans have lost their jobs, supply chains have broken down, consumption has plummeted, oil prices have been negative and the global levels of debt, already sky-high, have reached stratospheric heights. On March 16, when the VIX opened at 57,83 and closed at 82,69, the Dow Jones Index fell nearly 3,000 points, “the worst trading day in percentage terms since the ‘Black Monday’ crash of 1987 when the Dow got a 22 percent haircut.” And then, magically and absurdly, the markets recovered: In the beginning of July, The Economist reported that “American stock markets recorded their best quarter in at least two decades. From April to June the S&P i500 and Dow Jones Industrial Average rose by around 25%, and the Nasdaq by over a third.” Once again, the Fed came to the rescue, this time even keeping the junk bond-market afloat, while the average American was left to drown in a sea of debt, joblessness and little to no health care. Once again, the final reckoning was postponed and another veil was cast over the stark economic reality. This is the current predicament, a situation which COVID-19 has intensified, but in no way initiated. It is a crisis that is intimately and inherently connected not only to the economic crisis, but also and above all to the ongoing ecological one: the loss of biodiversity, deforestation, the food industry, agricultural capitalism, the destruction of ecosystems and wildlife habitats—all of these events (and many more) are contributing factors in the outburst and dispersion of SARS-CoV-2. “Forget the butterfly effect,” Adam Tooze argues: “this is the bat effect – our stranglehold on nature has unleashed the coronavirus outbreak. And the pandemic is forcing us to rethink how to run our networked world.” As is the case with the climate crisis, the corona crisis is no natural disaster. It is yet another example of what Marx and Engels, in The Communist Manifesto, referred to as “the sorcerer, who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells.” Yet another example of nature getting even. And ‘we’, the humans living in and through the crisis, have to ask the question that Mike Davis—who wrote about the avian flu in The Monster at our Door (2005)—articulated lately: has capitalist globalization become biologically unsustainable?

5/ Zoom is shit. Meanwhile (and as several texts included in this dossier have already described), the lockdown continued, university teaching took place online, and students were forced to sit at home, each in front of their own screen, isolated and alienated. Of course, many students around the world were already indebted and feeling lost, and without any future whatsoever. A futureless and fucked-up generation indeed. In Fall 2019, a Danish report was published, documenting that approximately 10% of all students in the Faculty of Humanities, University of Copenhagen, are struggling with mental health issues. This number only corroborates a general tendency in Danish society and the 18,4% increase in diagnoses of depression during the last decade. Other data even suggest that almost half of the students at the university of Copenhagen (48%) have experienced physical stress symptoms. For these reasons, and before COVID-19, I decided to engage some of the students at Department of Arts and Cultural Studies in a series of conversations/interviews in the Spring semester of 2020. The picture that took shape is not pretty. One interviewee, a second year-student with multiple diagnoses, told me: “All of us students are feeling like shit and yet everyone is alone in their own misery.” It did not get any better after the lockdown, quite the opposite. While some students may have thrived in the interregnum—with less obligations, less stress, less social interactions, less speed—it was certainly not the case with the eight students that I talked to. One student with social anxiety was adamant that Zoom was only accelerating her anxiety, especially but not only when it came down to the so-called “breakout rooms.” All of the interviewees emphasized that they were feeling more isolated, anxious, precarious and/or depressed. Or as an MA-student diagnosed with depression wrote to me: “I will definitely say that this [the lockdown and the transformation of classes from physical to virtual settings] is far, far worse than being at KUA [the campus for the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Copenhagen],” only to add, more emphatically: “tl:dr: online teaching sucks”.

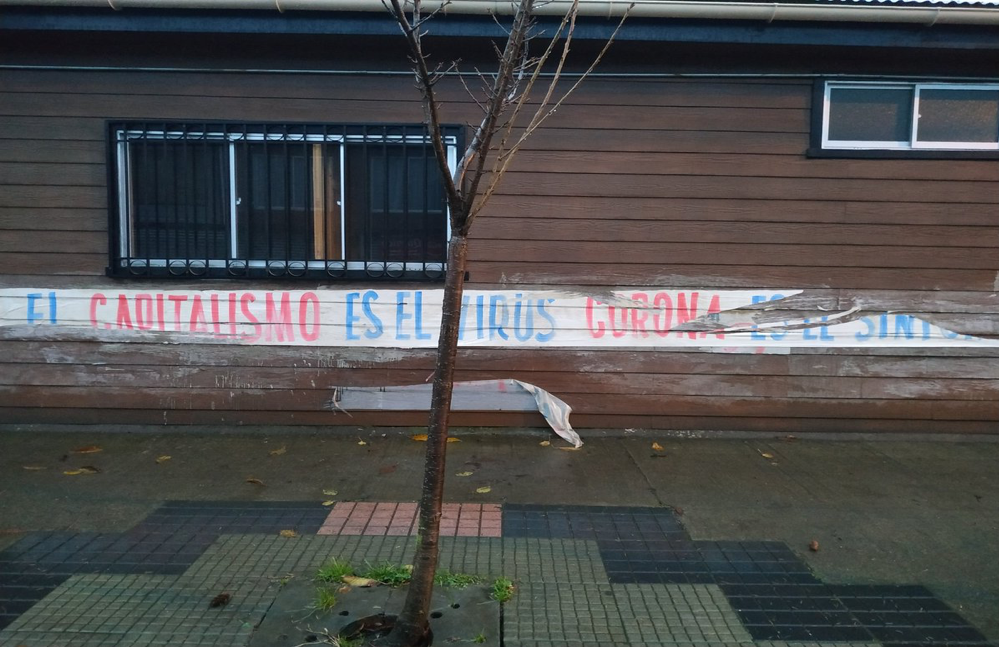

6/ Capitalism has become psychologically unsustainable. How to collectivize these experiences of mental illness, within the university and beyond? How to mobilize the students and how also to eliminate their suffering and the conditions that make them suffer? How to create infrastructures of care that don’t produce patients nor handle health as a business or a commodity; how to treat people who are sick in ways and in environments that are not themselves sick; how to deal with depression, and mental illnesses in general, outside the norm of returning people to normality, getting them (back) to being good, happy and productive workers? Or, more crudely, how to reclaim the future? The solutions offered by neoliberal ideology are clearly not helping. Notions of manning up, courses in positive psychology, self-help gurus and other forms of individualized therapy: they are not really helping. (The question of medication, antidepressants, and Big Pharma is a topic too large to deal with here.) At the University of Copenhagen—a full-blown neoliberal and financialized institution—a stress think tank has been launched recently and already it is evident that it too focuses on subjective and individual changes (releasing a mindfulness-app for instance), not structural and institutional ones. This isn’t helping either. But what then? The psychopathological problems of the present need to be taken seriously, but it would be exaggerated and maybe even counterproductive to speak of a mental health epidemic, as Nikolas Rose in a podcast has pointed out. A lot of the problems that are being framed as mental health problems are in fact social, political, economic and/or ecological problems (Nona Fernández reminds us: “No era depresíon era capitalismo”). Thus, it is important not to indulge in the tendency to privatize, psychologize and pathologize suffering, important not to reinforce the tendency to over-diagnose mental illnesses such as depression. That said, the problem of mental health is, unquestioningly, an acute problem, and one that has only been escalating since COVID-19. Not only among students, obviously. There has been a rise in suicides: “Deaths in mental health hospitals have doubled compared with last year – with 54 fatalities linked to since March began.” Several epidemiological studies have, unsurprisingly, found heightened rates of depression, anxiety and stress during the pandemic–from Colorado to China. Here, it bears repeating that ‘we’ are not all in the same boat. Just like COVID-19, and any other illness for that matter, mental health problems are distributed differentially, hitting disproportionately hard among communities who are struggling and vulnerable to begin with. To the question of mental illness belong questions of race, class and gender that cannot be ignored. Overall, then, COVID-19 poses a wide range of public and mental health questions, and not just to the disciplines of psychiatry or psychology. There is still a lot to think about, numerous questions left unexplained and unanswered. Yet there is little doubt that capitalism, at this point, simply seems to have become—always already was—psychologically unsustainable.

Thank you to Arne De Boever and to all my students, especially the ones who agreed to share their stories and experiences with me during Spring semester of 2020.

Mikkel Krause Frantzen (b. 1983), PhD, postdoc at the Department the Department of Arts and Cultural Studies at the University of Copenhagen, where he works on finance, fiction and the psychopathologies of the present. He is the author of Going Nowhere, Slow – The Aesthetics and Politics of Depression (Zero Books 2019), his work has appeared in Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, Journal of Austrian Studies, Studies in American Fiction, boundary2, SubStance, Los Angeles Review of Books and Theory, Culture and Society.

-

Stephen Wright — Devising the Post-Capitalist Imaginary/A Device for the Post-Capitalist Imaginary

The text below was initially presented at the “Algorithms, Infrastructures, Art, Curation” conference, organized by Arne De Boever and Dany Naierman, and hosted by the MA Aesthetics and Politics program (School of Critical Studies, California Institute of the Arts) and the West Hollywood Public Library.

The text is published here as part of a dossier including the lecture by Brian Holmes to which it was responding.

–Arne De Boever

by Stephen Wright

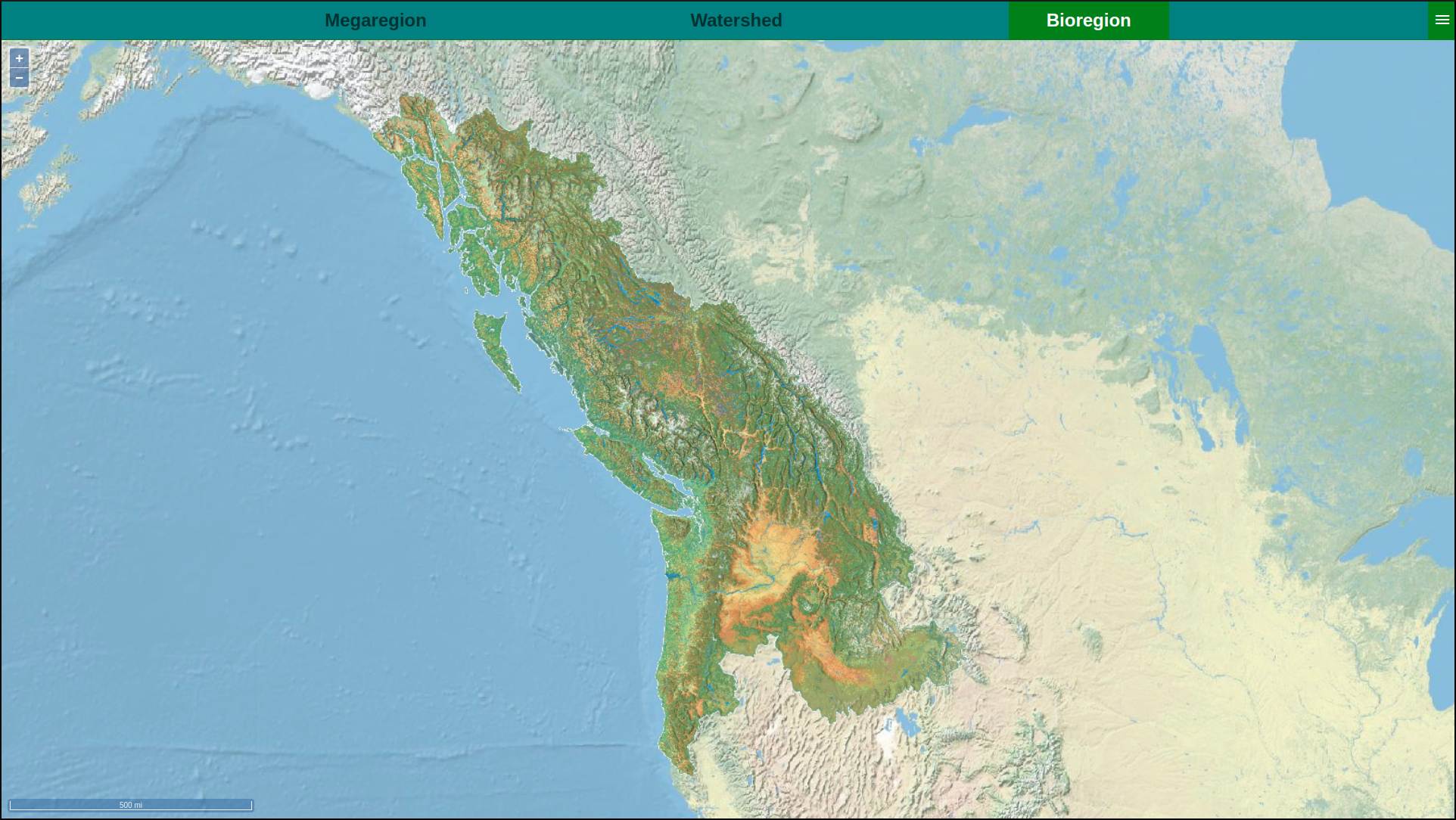

Above all, what I take away from Brian Holmes’s Cascadia project, and from the broad conceptual and affective setting that informs it — both nicely laid out in his user-friendly paper — is this: that we don’t so much lack a critique of capitalist globalization; we don’t even so much lack theories of communism; what we lack is a post-capitalist or post-globalization imaginary. We need, in other words — and those words will prove crucial in their own way — to experimentally implement full-scale (even if on a modest scale) devices to give embodiment to that imaginary. We need, that is, to devise a post-capitalist imaginary. And the good news is — at least, this is what I would like to be able to assert! — that this is precisely what his new projects on Bioregionalism put forth. But the reality is far more complex and it really does him no service to portray his critical cosmovision as incurably optimistic. Brian’s texts have always exuded a sense of pessimism, and delving deep into his findings over the course of detailed conversation where his critical edge is unchecked or unaccompanied by concrete experience of boots on the ground, one often feels that more critical knowledge in and of itself doesn’t lead to the heuristic elation one might expect; it sometimes feels more like backsliding into a wormhole — as if too much critical lucidity alone, or too much disembodied critical distance, occasions a kind of paralysis. This would be the sterility of critical theory for its own sake — fine for those of use who like that sort of thing, but not at all on a par with Brian’s demanding ethics of engagement.

Let me quickly but systematically unpack some of those remarks which I admittedly draw as much from my several decades long friendship (and occasional collaboration) with Brian as from the paper he has just presented.

When I first met Brian in Paris where he lived until 2008, he was a translator — he still is, in an expanded sense of course, but I mean in those days he was making a good living translating texts between one language and another. This obviously couldn’t last because, however one may learn by the more-than-intimate contact with the translated subject (I mean the internal merging with their perspective), one is inevitably frustrated by a kind of paradoxal algorithm of translation: the better the translation in a sense, the more one’s own subjectivity disappears.

So Brian began to inject his writing skills into political activism, working with groups on the fringe of art and activism in Barcelona, Paris, London and elsewhere, and working as a core member of collectives as different (and hard-hitting) as the conceptual design activist group Ne Pas Plier, the critical cartography collective Bureau d’études, or the post-operaist journal Multitudes, amongst many others. I’m saying this stuff not because I’m planning to write Brian’s Wikipedia page (which presumably already exists, I don’t know) but because I want to draw out what are the underlying ethics of his practice as it evolved over time.

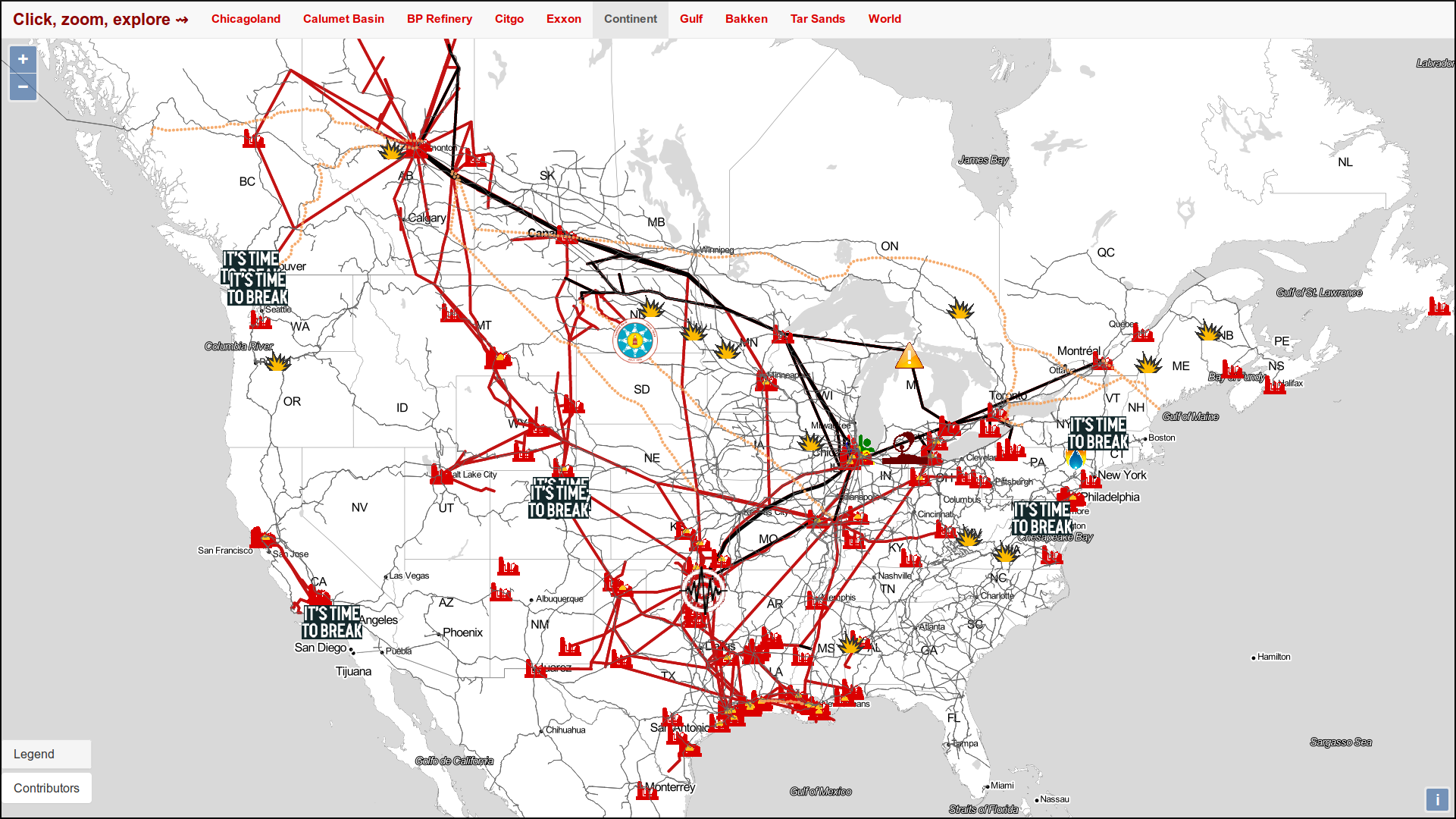

Even as he was engaged in these collectives, another more ambitious but more personal investigative project was developing — in keeping with the rise of the continental trading blocks that were the jugulars of globalizing capitalism. In those years, Brian (and not only him) kept feeling like he was waking up on the wrong side of capitalism — no matter where on Earth he woke up! That graffitied slogan became the logo to the website Continental Drift, as the project came to be known. It was a staggeringly ambitious project, but simple in its conceit. As economic and financial power was usurped from sovereign states and concentrated on continental scales, then it was fair to assume that subjectivity was henceforth also being produced at that same macro- or mega- scale: NAFTA subjectification, EU subjectification, China-Japan-Korea subjectification. And Brian wanted to mobilize a critical analysis of the former to investigate the latter, and vice versa. So, Situationist style, Brian began to self-organize with a host of likeminded comrades and local informants, drifts across the continental subjectivity-production zones, in the Americas, Asia, etc. Rather than approach the macroeconomic and macropolitical exclusively on the level of critical analysis, he would do cartography with his feet. As if there were a need to feel, see, smell, hear — affect the affects — to keep things from being overwhelming.

Perhaps for this reason too — or perhaps another — Brian chose as his lens of predilection for these drifts (their subsequent restitution, but on the ground too) the most micro-configurations he could find: artworks. Artworks are perhaps the pithiest, the most affect-intense and knowledge-energized symbolic configurations there are, and from their material can be teased out any number of insights, to which they themselves are often partially blind. Actually, this is the only thing that redeems art at all; the only justification for an other unjustifiable pursuit (I mean that in a good way!).

Continental Drift was and was not an art project: it was an art usership project, not in any explicit way an artist-initiated endeavour. But one can see all the methodology in germination of the current projects: the vertiginous confrontation of disparate scale, the paramount importance of clarity, the imperative to make territory palpable, pedestrian. Of Continental Drift one might say that although its ontology was not of art, its coefficient of art was already high.

It came as no surprise that it was often taken as art, though not performed as such. Brian had become as he wrote to me “una suerte de artista que sabe de libros”. When he finally did become an artist in 2015, it was less of a coming out — though with hindsight one can see a logic unfolding — than a tactical choice for a site of engagement. For this is what it has always been about: not the specificity of some mode of doing or being, but its compatibility with other modes of doing and becoming. More precisely, about social engagement. In his text, he writes, “One of the most important things that artists and intellectuals can do is to express and analyze the constituents, forms, desires and aims of a bioregional culture.” Importantly, there is no conceptual distinction between “artists and intellectuals”; maybe just a slight shift in focus.

Important too is the plural form. Brian didn’t spell it out in his text so I will (though it is abundantly implicit and should not really require emphasis): critical engagement of any kind cannot be done meaningfully alone; it is an inherently collective undertaking. That is the lesson of the avant-garde — the mutualization of competence and incompetence. Even the most strikingly original turn of phrase or analysis is never anything more than a collective enunciation in disguise. So people, work together! It’s at once the ways and means of devising the post-globalization imaginary…

After Continental Drift, after the exhaustion of globalization, Bioregionalism appears a logical deduction — though that is an illusion due as more to the clarity of Brian’s exposition than to the reality of it — since it remains, precisely, an imaginary to be built. That clarity of exposition may be the upshot of years of writing, but it also embodies a deep-seated ethical imperative — a commitment to popular education, the exigency to vulgariser and render accessible — the essence of Brian’s ethics of engagement, which could more simply be described as generosity.

Inseparable from this — and no less important, especially in this setting today — is the fact that all of these broad-scoped extradisciplinary investigations were done without any of the epistemic high-tailings and legitimation of academia. But they have all been informed — and Brian is inflexible on this — by a standard of rigor to which academia could rarely hold itself. We are talking about an emblematic instance of autonomous knowledge production — not the only one, to be sure, but one that is particularly exemplary. Like Continental Drift, we can look forward to finding in Bioregionalism a voracious appetite for theory and often dense analysis, crunched and if not quite digested, reformatted in reader- and user-friendly fashion. What a great way to practice theory! Make it palatable; make it palpable, make it useful.

For sure there’s something of the escapologist in Brian’s work: Escaping the Overcode (2009) was the title of his third and most comprehensive collection of essays; escaping epistemic and academic capture; escaping institutional framing; escaping ontological capture as “just art”. But the singular temporality that in each of those cases characterizes escapology is that escape precedes capture — indeed only from the perspective of power is capture primary. Escape is always already underway; we never know when people may choose to escape; but we can be sure that they already are — which is what renders power so paranoid — and provides such traction to embodied projects of devising a new imaginary, rather than merely falling back on the disengagement of critique.

A few years ago, my son Liam and I used to watch a mainstream TV show called Prisonbreak. It was a bit of a dudefest of a show, but beyond the action-packed episodes, there was something about the conceit that attracted my attention — and that in a way reminds me of Brian’s work. It’s the story of a man who wants to spring his brother from high-security prison, where he has been unjustifiably put by none other than a Wyoming-based vice president of the United States… So in order to orchestrate the escape, the protagonist first has to get into the prison himself, as a prisoner, and then use a sophisticated map of the super-max establishment to find the way out. The map, it turns out, is an incredibly detailed tattoo on his own body… This is the paradoxical and dialectical relation between the need to penetrate to the very core of the oppressive system, in order to embody the map out. On a wholly different scale with utterly different collaborators, but with a similar logic, this is the plan for Cascadia. Our bodies and practices as devices of the becoming bioregional imaginary.

-

Chad Kautzer — Trump, Public Health, and Epistemic Authoritarianism

This essay is a part of the COVID-19 dossier, edited by Arne De Boever.

by Chad Kautzer

“What you’re seeing and what you’re reading is not what’s happening.”

– President Donald J. Trump, July 24, 2018

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, we have witnessed how autocrats can effortlessly dismiss dire public health news, regardless of its factual basis, and disparage its messengers or even smear them as treasonous without reservation. Such reactions undermine public health and threaten the researchers and practitioners generating knowledge in its service. Yet, however demoralizing it may be to witness the present disregard for public health as well as the belittlement and even endangerment of public health advocates, there are lessons to be learned about authoritarianism and the ways we can oppose it.[1]

Trust in public health researchers and practitioners derives not from their supposed objectivity or claims to certainty, but from a commitment to transparency, an openness to critique and revision, and the promotion of health equity in the face of economic and sociodemographic disparities. As producers of credible knowledge in the lab or in the field, they earn a form of authority we call epistemic. To autocrats, who consider their own political authority to be subject to neither critique nor limit—Trump, for example, recently claimed that his authority is “total”—epistemic authority represents an unwelcome check, because it can raise legitimate questions about their policies and assertions. Attacks on journalists, academics, and civil and human rights organizations are similarly motivated by the autocrat’s desire to undermine or appropriate their various kinds of authority. To this end, these groups are often described as “elites” or “enemies of the people” to separate them from the “real people” whom the autocrat is said to personify.

Autocratic regimes do, of course, rely on expert knowledge, but vigorously police them to ensure that such expertise does not contradict the leader or erode trust in the authoritarian relations, and alternate epistemic universe, they cultivate. This task becomes difficult in times of crisis, when autocrats feel compelled to demonstrate absolute authority, yet solutions to complex problems call for input from a plurality of voices (including those most impacted), open and critical deliberation, and public trust.[2] Autocrats are therefore engaged in a battle on multiple fronts: confronting public crises, while simultaneously assailing non-political forms of authority that could challenge them.

Autocratic Tactics Against Public Health Advocates

When the crisis is a public health emergency, it is public health researchers and practitioners who gain public prominence and in turn the autocrat’s covetous wrath. The autocrat employs three identifiable tactics in his campaign against the epistemic authority of others, namely, those of delegitimizing, silencing, and usurping.[3] The tactic of delegitimizing public health advocates is pursued through spurious accusations and public denigration. It is often combined with, and said to justify, the second tactic, namely, silencing through threats, removal, incarceration, or even death.

At the beginning of the pandemic, indeed, before the novel coronavirus had a name or was deemed to have caused a pandemic, there was the tragic case of Dr. Li Wenliang in Wuhan. It was early January of this year when the Chinese government attempted to delegitimate and silence Dr. Wenliang, a 33-year-old ophthalmologist. Late last year, Dr. Wenliang alerted fellow doctors about several patients with coronavirus infections, although the virus strain was unclear. He recommended his colleagues and their families take precautions.

Within days, Dr. Wenliang was publicly accused of spreading rumors, detained, and threatened with prosecution. Police from the Wuhan Public Security Bureau made him sign a letter stating that he made “false comments,” had “severely disturbed the social order,” and must promise to never do it again. He returned to work and contracted the virus, but days before he died on February 3, he publicly shared the letter they made him sign, sparking national outrage. In an interview before his death, Dr. Wenliang said “I think there should be more than one voice in a healthy society, and I don’t approve of using public power for excessive interference.”[4]

For the past several years, Turkey’s autocratic President, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has used delegitimizing and silencing tactics against tens of thousands of academics, scientists, journalists, doctors, artists, and activists, labeling them terrorists or terrorist sympathizers with the help of anti-terrorism legislation Amnesty International calls “vague and widely abused in trumped up cases.”[5] Individuals have lost their jobs, their public platforms, and their personal freedom.[6]

Dr. Bülent Şık, for example, was a deputy director at the Food Safety and Agricultural Research Center at Akdeniz University, but fired from his position and indicted for participating in terrorist propaganda by signing an Academics for Peace petition. He had recently completed years of research for the Ministry of Health measuring environmental pollutants in several regions of Turkey and found widespread and serious risks to public health. When he attempted to alert the public to the danger in a series of newspaper articles, he was sentenced to 15 months in prison. During the coronavirus pandemic, doctors Güle Çınar and Yusuf Savran were detained and made to issue public apologies after their statements about the coronavirus were deemed inconsistent with the official state line.[7] Most recently, public health specialist and member of the Turkish Medical Association COVID-19 Monitoring Group, Prof. Kayıhan Pala, is under investigation for stating that the number of infections and fatalities in the Turkish city of Bursa is higher than publicly reported.[8]

Brazil’s neofascist president, Jair Bolsonaro, has employed all three tactics against health care officials at a time when the country has the second highest number of coronavirus infections and deaths in the world. He has ridiculed warnings by medical experts, calling them “hysterical”; removed officials who advocated for evidence-based policies that contradicted his political imperatives; and recommended unproven remedies such as hydroxychloroquine as if he possessed specialized knowledge on the subject. “The virus is out there and we will have to face it, but like men, damn it, not kids,” he said at a public event, where he flouted the social distancing rules set by his then health minister, Luiz Henrique Mandetta, a medical doctor.

It was Mandetta’s social distancing policy and lack of support for Bolsonaro’s hydroxychloroquine remedy that led to the minister’s ouster.[9] In his farewell press conference, Mandetta urged Ministry of Health employees to not be afraid and to vigorously defend science. “Science is light,” he said, “and it is through science that we will find a way out of this.”[10] Mandetta’s replacement, Nelson Teich, also a physician, quit as health minister weeks later after opposing Bolsonaro’s continued push for hydroxychloroquine and his failure to consult with the Ministry of Health before reopening businesses.[11] Bolsonaro tested positive for COVID-19 in early July.