The Body’s Prehistories: On Hervé Guibert’s Written in Invisible Ink

by Peter Valente

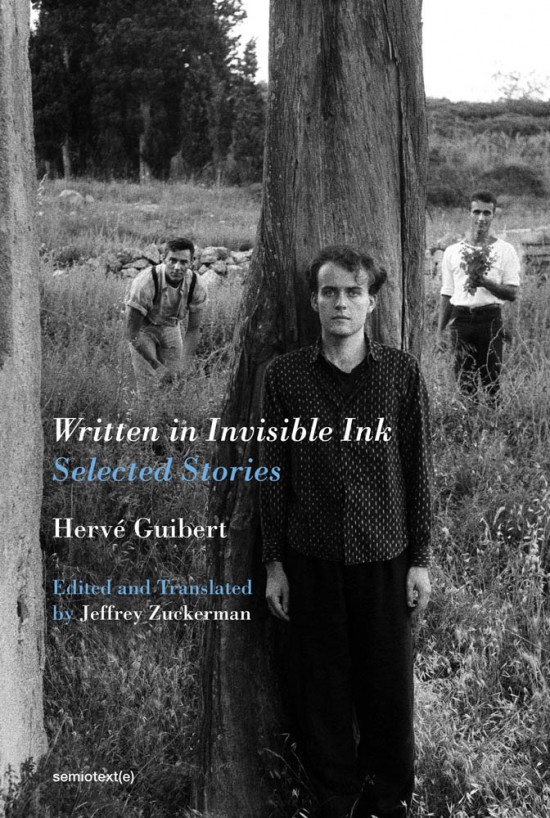

One of the many pleasures of reading Hervé Guibert’s collection of stories, Written in Invisible Ink (Semiotext(e), 2020), is following his development as a writer from the earliest stories in this volume, which date from the late 1970s, to the latest (which were collected in 1988’s Mauve Virgin). According to his widow Christine Guibert, he did not write any stories after 1988 and focused more on longer works such as the novel To The Friend Who Did Not Save My Life (1990).[1] Several of the stories published in this present volume have never been published before. Interestingly, the ones collected here, chosen by the translator Jeffrey Zuckerman, coincide with Guibert’s time as a journalist; many of the texts have the journalist’s attention for details that will capture a reader’s attention.

The stylistic difference between Propaganda Death, the earliest of his books, and the later stories is between the raw passionate writing of the former and the more controlled prose of the latter. Guibert was one of first French writers of “autofiction,”: he used writing from his diary as well as memoir and fiction to complicate the narrative “I.” The writing in Propaganda Death is almost cinematic in its cataloguing of physical violence to the body mixed with an unbridled sexual urge: “My body, due to the effects of lust and pain, has entered a state of theatricality, of climax, that I would like to reproduce in any manner possible: by photo, by video, by audio recording” (27). Its scenes of the savage torturing and disemboweling of the human body, amidst slaughterhouses and hospitals, exhibit the frightening transparency of what lies beneath the skin, revealing its secrets: “no need for candles to brighten this night of the body; its internal transparency illuminates all” (27). In “Final Outrages” Guibert imagines himself as the young girl Ophelia, “stolen away in the bloom of youth by an ailment gnawing slowly at her interior (while making her exterior radiate!)” (81). In “Five Marble Tables”, he writes, imagining himself dead: “I won’t let go of my body, I cling to it, I push out everything I can inside but it all stops immediately, I’m clean forever now, my muscles tear apart, I can’t go back in myself anymore and I leave this deserted place, all the fight gone, all the fury slain” (70). Death in life is imagined as transformative; in a later work, Crazy for Vincent (Semiotext(e), 2017), published in 1989, a year after the latest stories in this volume, Guibert writes: “I struggle with the mystery of the violence of this love…and I tell myself that I would like to describe it with the solemnity of the sacred, as if it were one of the great religious mysteries…I don’t have too many sexual thoughts, of fucking or of defilement, violent hallucinations that would bring sex or lechery into play, but rather the suspended grace of bearing witness to a transfiguration” (85). The thrust of these stories is away from materiality, and toward a refiguring of the male body as a site for spiritual transformation.[2]

Propaganda Death is also an ecstatic fantasy of destruction, desecration, and horror, calling for nothing less than the annihilation of the petit-bourgeois world through a complete reversal of cherished mores and customs, and its obsession with good hygiene, both physical and mental: “I’d like to smear my gonorrhea over the entire world, infect the planet, contaminate dozens of asses at a go, …my bed every morning is a field of carnage, a slaughterhouse” (51). He continues: “Let’s open abscesses in all this stupid flesh!…Let’s love ourselves and hate them! Let’s orgasm as we pull our heads from our bodies!” (47). Wayne Koestenbaum writes:

Filth is Guibert’s passport to infinity. Filth, as literary terrain, belongs to de Sade, but Guibert reroutes s/m through the pastoral landscape of religious interiority, as if ghosted by hungry Simone Weil, or by Wilde’s scarified, Christological denouement. (To skeptics, such spirituality might seem papier-mâché, but I’m a believer.) Guibert sees a cute young man at a party and “instead of imagining his sex or his torso or the taste of his tongue, in spite of myself it’s his excrement I see, inside his intestines.” (Kostenbaum 2020)[3]

These passionate, anarchic early texts are difficult to read. They are unpolished, raw, unedited, obsessed with the violence of desire, and with orifices; but nevertheless, they are works of great intensity, written when Guibert was 21 years old, and likely to shock a reader into a recognition of his/her own body, and its impermanence, and the weakness of the flesh. They are performance, spectacle, and indeed, propaganda in defense of homosexuality and the violence of desire.

Guibert seeks to “to uncover my body’s prehistories,” the traces of the animal inside the human. In the story, “Flash Paper,” he writes that while kissing Fernand, he imagines that “Out of the extended, warm pleasure of the kiss came other visions: we were two animals that had met on the terreplein, each from our own half of the forest, two horned beasts, two giant snails, two unhappy hermaphrodites” (Invisible Ink 230-31). And, continuing with this theme in the same story: “His wide-opened eye had awakened mine and did not leave it: we had become insects” (232). He and Fernand are, “two poor shameful animals” (233). Finally, he writes: “we danced like two spider crabs being boiled, destroying everything in their path” (234). The erotic charge of an encounter turns men into animals searching for their release. There is danger and excitement in the kill, the sexual energy of it: “If I fuck him, if I decide to fuck him, it’s first to annihilate him.”[4] This is “no simple sadism…no simple equation of fucking and killing, of penetrating and violating – instead, the wish to fuck or be fucked…is a sensation of being voided, chiseled, scalded, disemboweled. Is this consciousness a queer privilege? Is it shamanistic? Is it in fact not trans or queer or anything of the sort, but simply poetic?” (Kostenbaum 2014). Guibert could certainly be melodramatic, as well as poetic. Sex in his work is theatrical; he plays a game of hide and seek with a reader; but he doesn’t sugar coat desires that are complex or grotesque and this is what makes his work so valuable as a document of honest writing in a time such as ours when the line between truth and falsity has been blurred.

In the section, “Personal Effects” Guibert examines objects rather than bodies and reveals their hidden meanings or forbidden histories. About the “Cat o’Nine Tails”, for instance, he writes: “The cat o’ nine tails has been hung, among the cobwebs dusters, from ceiling hooks, in the dim backroom of the hardware store. It carries within itself, in its unmoving straps, the screams of battered children, it exhales the pleasure of perverted lovers” (Invisible Ink 97). Gloves are a normal part of winter wear or when working in the garden, or in construction et cetera, but Guibert reminds us that “it should never be forgotten that the hands they’re keenest to help are those of thieves and stranglers” (103). With regard to the “vibrating chair,” he notes that the dukes of Pomerania found “extravagant” uses for it, including attaching a large dildo to its seat (107). This section of the book is representative of Guibert’s poetics. As a journalist, he was accustomed to examining the forbidden histories behind things which elude the eye of the observer. In “Newspaper Clipping,” he talks about certain facts concerning the death of a person and cautions about imaginatively reconstructing the scene. “Let’s come back to reality!,” he writes, concluding that “…everything, for now, remains purely hypothetical” (56). The secret will not reveal itself easily and it requires patient and research to reveal a truth perhaps stranger than fiction.

In the world of these stories, love is essentially a complex power game, where the weak person is always at a disadvantage. Guibert is not a psychological writer, concerned with exploring in depth the subjective feelings of lovers. There is no utopian idea about love in these stories. Love is often deceptive, leading to betrayals and even violence. “For P. Dedication in Invisible Ink,” concerns a young writer who has complex desires toward an older, more established writer, and is called upon to help him write a book. At the end of the story, the young writer speaks of their erotic dynamic in the following way:

The king of the jungle had been tamed, or maybe it was the lion that subdued its tamer, but one or the other, at his point of submission, attacked the other in hopes of breaking him, and these visits grew increasingly rare. The break-up happened over the course of the seventh year, bit by bit, as if by blows, and neither the assailant nor the stronghold, at risk of breaking their necks, wanted to bow down. (159)

Love often begins with a kind of “tacit contract” that one or the other eventually betrays. In one of the central stories, “The Sting of Love,” love is imagined as a liquid that is injected in the lover. The story traces its various effects on those who have been “infected” and concludes:

A happiness so great becomes unbearable unless one is shackled, or better yet, in bed, because the effect of this injected liquid doesn’t end with any climax, it persists all the way into sleep. It is impossible here to determine the specific link between consciousness and dreams. Anyone who wants to fight against this surreptitious transition with conscious effort, who is afraid because the dream, at first still just as wholly gentle, slowly turns into nightmare, flickering with swift animal shapes, anyone who wants to prolong this amorous stupor indefinitely with a second injection is struck with melancholy, as with a tarantula’s bite, and loses speech, nails, job. (135)

Physical attraction is just as capricious and mysterious and not necessarily the result of erotic language: “We sat facing each other in the small, unlit kitchen, and I immediately felt within his physical presence a sense of elevation, adventure, freedom. The words he had said had nothing overtly erotic about them, but they suddenly, mysteriously had my penis swelling” (182). There is no attempt to seek a reason for his desire which would amount to a kind of defense; Guibert was open about his homosexuality and its relation to danger as well as pleasure. Furthermore, this physical excitement can suddenly turn into potential violence: “two years earlier, walking behind him, I had suddenly wanted to use all my force to hit the back of his neck with the heft of the camera hanging by a strap around my wrist” (178). In “For P. Dedication in Invisible Ink”, Guibert writes, “My feelings about this man were skewed: even as I could have said that I loved him, when I found myself before him, at long last, I wanted to go for his throat” (153).

Danger extends to sexual encounters in the park. In “A Lover’s Brief Journal,” Guibert relates an incident in the Tuileries, where, after “a guy whispers the word cop,” he and another man get dressed, and leave the park; but Guibert is then assaulted: “the first one punches me in the face, another kicks me in the balls, right after a third guy takes a running start to headbutt me, I fall down, I get back up, I shout for help without thinking about it, they run off, I run in the other direction, I turn around, I see one of them hurrying to pick up the coins that fell out of my pocket, hungry, greedy” (48-49). The violence has as much to do with money as with sexuality: the link here is between capitalist greed and homophobia. Though capitalism created the material conditions so that both men and women could lead independent sexual lives, it also, at the same time, imposed heterosexual norms on society to create an economic, ideological, and sexual regime, centered in the family. In the present time, when Trump, a symbol of capitalist greed, is seen as a spokesman for the white, heterosexual male, and encourages violence against marginalized groups on the basis of their skin color, religion or sexual preference, it is no surprise that we see a rise in violence against gay and trans men and women.

For the narrator of “Flash Paper,” love is, “ a voluntary obsession, an unsure decision” (239). But Guibert writes of the man who died in “A Man’s Secrets,” “All the strongholds had collapsed, except for the one protecting love: it left an unchangeable smile on his lips, when exhaustion closed his eyes” (254). And the aging star in “The Desire to Imitate” says, “In this impossibility of love there will have been all the same a little love” (212). In these stories, love and cruelty are woven together; this unholy union was born of Guibert’s hatred of his own body, his self-pity, his anger, his theatricality, his passion for the grotesque. He is attacking bourgeoise values, and inherited ideas about morality, thus turning our assumptions about love and hate upside down. Men who knew him said he was cruel but he hated pity and charity; Marie Darrieussecq writes that he preferred real friendship and despised cowardly people (“Guibert’s Ghost” 2015). For Guibert, true love may be impossible, but all the same, he valued the love that was possible in genuine friendships. He sought the truth in himself by testing the limits of his body and of his desires. In a world where our freedoms are being assaulted by both far right conservatives and neoliberals, a writer like Guibert is necessary and should be read, because he questions our conventional ideas about the nature of sexuality, love and hate.

Death hovers on the periphery of the stories in Written in Invisible Ink, and is often a central theme, and linked mysteriously with desire. In “Five Marble Tables,” Guibert imagines himself on a laboratory table, communing with other bodies, one of which is a young child. As I suggested earlier on, in the story Guibert feels in some way liberated: “I’m clean forever” (Invisible Ink 70). Guibert speaks of the dream, a kind of death-state in itself, as concealing, “a geography of pleasure, an itinerary with its impasses, its openings, its stairwells, its gulfs, its forbidden directions. Desire is there alone, idealized, freed of all materiality” (75). It can also contain, “desirable monsters,” such as the man whose “suffering was immense” because his “head is four times larger than his body” (129) and who believes the hand that gives him his food through a trapdoor is the hand of God. The monstrous, the forbidden, is a gateway to the spiritual.

In this palace of desirable monsters are men with “dog’s or wolf’s heads” or with “scales or moss growing on their skin” (129, 128). The animal and the vegetal are mixed and the monstrous appears beautiful. A world based on reason, a human creation, gives over to the animal, the irrational, the monstrous. This space contains an alternate time that exists simultaneously with the real world. In “Posthumous Novel,” one of my favorite stories, Guibert writes of a space where, as a result of a “deatomization effort” in Holland, “countless words, incomplete sentences” are “hanging like clumps off of trees and, broken and sown over the ground” (143). Words are not necessarily attached to sentences but exist alone as fragments. In the story, Guibert writes that when one is travelling by train, one’s thoughts release, “more or less clouded and blinded” words into the air of the surrounding countryside and that they take root in the “roadside dust, a branch shaken by the wind, setting sun” (144). These words or sentences, cast into the world by the living, are “nourishment for the dead…a vital message of what happens in the hereafter” (144). By accessing these “sentences” through “x-raying” the “final trajectories” of the young writer in the story who committed suicide, the author is able to partly reconstruct the dead man’s novel (146). The narrator is like Orpheus, in Cocteau’s film, listening to the transmissions on the radio which are actually the voices of the dead. These words of the dead need to be remembered. History must be remembered in order not to repeat the same mistakes to the point of unconsciousness.

It is in this forbidden space, this underworld that does not obey the laws of physics, that Guibert, a kind of Orphic figure, is able to imagine a language that is not bound to its materiality; it exists in the air, unrealized, incipient, spiritual, the image of a ghost. It is here where the monstrous, the aborted, the abject thoughts reside, and where the dead dwell. It is a land that “had never been described or transcribed on a map” (220). It is a forbidden and magical place, where one has the “courage to be oneself, to present oneself, and to liberate every secret, to invent them” (150). Guibert wrote this book in “invisible ink,” from that place, as if the stories themselves are only the visible traces of what lies behind them: the sexual encounters that produced them.[5]

In January, 1988, Guibert was diagnosed with AIDS. As a result, he immediately found himself the focus of media attention and appeared on numerous talk shows. Early in his career, Guibert was openly gay and unashamed of his homosexuality and this, according to his translator Jeffrey Zuckerman, “was not meant as a provocation” but as “a quietly revolutionary stance in line with his particular brand of rebelliousness, in which, to quote a line from the end of “Ghost Image,” ‘secrets have to circulate” (“Translator’s Preface”13). Furthermore, Zuckerman writes, “When I began this project, all of Guibert’s translated novels were out of print – even To the Friend Who Did Not Save My Life. At the time, it felt symbolic yet saddening: if gay rights were moving so steadily forward toward equality with the broader population, why preserve this particular, liminal past? Indeed, such an unprecedented nationwide – and even global – sea change in attitudes toward gay marriage and adoption risked effacing the long struggle that came before it, from Oscar Wilde’s trials and Alan Turing’s cyanide-laced apple to the Stonewall riots and the ACT-UP movement” (“Translator’s Preface” 15). And for this reason, the stories in Written in Invisible Ink are a valuable addition to Guibert’s work in English, and a good starting point for the reader unfamiliar with his work.

Peter Valente is the author of A Boy Asleep Under the Sun: Versions of Sandro Penna (Punctum Books 2014), which was nominated for a Lambda award, The Artaud Variations (Spuyten Duyvil 2014), Let the Games Begin: Five Roman Writers (Talisman House 2015) and Catullus Versions (Spuyten Duyvil 2017). He has also published translations from the Italian, Blackout by Nanni Balestrini (Commune Editions 2017) and Whatever the Name by Pierre Lepori (Spuyten Duyvil 2017), Two Novellas: Parthenogenesis & Plague in the Imperial City (Spuyten Duyvil, 2017). He is the co-translator of the chapbook Selected Late Letters of Antonin Artaud, 1945-1947 (Portable Press at Yo-Yo Labs,2014), and has translated the work of Gérard de Nerval, Cesare Viviani, and Pier Paolo Pasolini. His poems, essays, and photographs have appeared or are forthcoming in journals such as Mirage #4/Periodical, First Intensity, Aufgabe, Talisman, Oyster Boy Review, spoKe, and Animal Shelter. His most recent book is a co-translation of Succubations and Incubations: The Selected Letters of Antonin Artaud (1945-1947). Forthcoming is a collection of essays, Essays on the Peripheries (Punctum 2020) and his translation of Guillaume Dustan’s Nicolas Pages (Semiotext(e) 2021).

Works Cited

Darrieussecq, Marie. “Guibert’s Ghost.” Tin House, 13 January, 2015: https://tinhouse.com/guiberts-ghost/

Guibert, Hervé . 2020. Written in Invisible Ink. trans. Jeffrey Zuckerman. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

—- 2017. Crazy for Vincent. trans Christine Pichini. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e).

Kostenbaum, Wayne. “The Pleasures of the Text.” Book Forum, June-August, 2014: https://www.bookforum.com/print/2102/herve-guibert-s-unbridled-eroticism-13298

Zuckerman, Jeffrey. “Translator’s Preface” in Written in Invisible Ink. trans. Jeffrey Zuckerman. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2020, 1-15.

Notes

[1] Guibert married Christine in 1989, so that she could protect his estate and so that the royalty from the sale of his books would go to her children. The publication of the mentioned novel, in which Guibert told the world he had AIDS, caused a scandal because in it he disguised Michel Foucault, who had the same disease, under another name (Muzil). However, the public discovered that this was Foucault; he had been dead for six years (reportedly from cancer) at the time of the publication of Guibert’s book.

[2] For Bataille, the indulgence in “perversity” also contained a strong drive for the metaphysical, for that which lies beyond the body.

[3] I would also add Artaud to the list above in his researches into “fecality.”

[4]Quoted in Kostenbaum, The Pleasures of the Text,” accessed on May 17, 2020, https://www.bookforum.com/print/2102/herve-guibert-s-unbridled-eroticism-13298

[5] In “A Lover’s Brief Journal,” Guibert writes, “I got completely undressed, I write and that gets me hard, I jerk myself off with one hand…” Hervé Guibert, Written in Invisible Ink, 49.

Leave a Reply