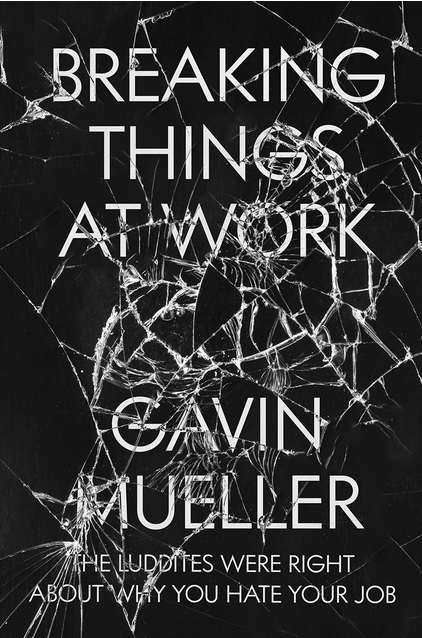

a review of Gavin Mueller, Breaking Things at Work: The Luddites Were Right about Why You Hate Your Job (Verso, 2021)

by Zachary Loeb

A specter is haunting technological society—the specter of Luddism.

Granted, as is so often the case with hauntings, reactions to this specter are divided: there are some who are frightened, others who scoff at the very idea of it, quite a few dream about designing high-tech gadgets with which to conclusively bust this ghost so that it can bother us no more, and still others are convinced that this specter is trying to tell us something important if only we are willing to listen. And though there are plenty of people who have taken to scoffing derisively whenever the presence of General Ludd is felt, there would be no need to issue those epithetic guffaws if they were truly directed at nothing. The dominant forces of technological society have been trying to exorcize this spirit, but instead of banishing this ghost they only seem to be summoning it.

The problem with spectral Luddism is that one can feel its presence without necessarily understanding what it means. When one encounters Luddism in the world today it still tends to be as either a term of self-deprecation used to describe why someone has an old smartphone, or as an insult that is hurled at anyone who dares question “the good news” presented by the high priests of technology. With Breaking Things at Work: The Luddites Were Right About Why You Hate Your Job, Gavin Mueller challenges those prevailing attitudes and ideas about Luddism, instead articulating a perspective on Luddism that finds in it a vital analysis with which to respond to techno-capitalism. Luddism, in Mueller’s argument, is not simply a term to describe a specific group of workers at the turn of the 19th century, rather Luddism can be seen in workers’ struggles across centuries.

At core, Breaking Things at Work is less of a history of Luddism, and more of a manifesto. Historic movements and theorists are thoughtfully engaged with throughout the volume, but this is consistently in service of making an argument about how we should be responding to technology in the present. While contemporary books about technology (even ones that advance a critical attitude) have a tendency to carefully couch any criticism in neatly worded expressions of love for technology, Mueller’s book is refreshing in the forthrightness with which he expresses the view that “technology often plays a detrimental role in working life, and in struggles for a better one” (4). In clearly setting out the particular politics of his book, Mueller makes his goal clear: “to make Marxists into Luddites” and “to turn people critical of technology into Marxists” (5). This is no small challenge, as Mueller notes that “historically Marxists have not been critical of technology” (4) on the one hand, and that “much of contemporary technological criticism comes from a place of romantic humanism” (6) on the other hand. For Mueller “the problem of technology is its role in capitalism” (7), but the way in which many of these technologies have been designed to advance capitalism’s goals makes it questionable whether all of these machines can necessarily be repurposed. Basing his analysis on a history of class struggle, Mueller is not so much setting out to tell workers what to do, as much as he is putting a name on something that workers are already doing.

Mueller begins the first chapter of his book by explaining who the actual Luddites were and providing some more details to explain the tactics for which they became legendary. As skilled craft workers in early 19th century England, the historic Luddites saw firsthand how the introduction of new machines resulted in their own impoverishment. Though the Luddites would become famous for breaking machines, it was a tactic they turned to only after their appeals to parliament to protect their trades went ignored. With broad popular support, the Luddites donned the anonymizing mask of General Ludd, and took up arms in their own defense. Contrary to the popular myth in which the Luddites smashed every machine out of a fit of wild hatred, the historic record shows that the Luddites were quite focused in their targets, picking workshops and factories where the new machines had been used as an excuse to lower wages. Luddism did not die out in its moment because the tactics were seen as pointless, rather the movement came to an end at the muzzle of a gun, as troops were deployed to quell the uprising—with many of the captured Luddites being either hanged or transported. Nevertheless, this was certainly not the last time that machine-breaking was taken up as a tactic: not long after the Luddite risings the Swing Riots were even more effective in their targeting of machinery. And, furthermore, as Mueller makes clear throughout his book, the tactic of seeing the machine as a site for resistance continues to this day.

Perhaps the key takeaway from the historic Luddites is not that they smashed machines, but that they identified machinery as a site of political struggle. They did not take hammers to stocking frames out of a particular hatred for these contraptions; rather they took hammers to stocking frames as a way of targeting the owners of those stocking frames. These struggles, in which groups of workers came together with community support, demonstrate how the Luddite’s various tactics served as “practices of political composition” (16, italics in original text) whereby the Luddites came to see themselves as workers with shared interests that were in opposition to the interests of their employers. The Luddites were not to be assuaged by appeals to the idea of progress, or lurid fantasies of a high-tech utopia, they could see the technological changes playing out in real time in front of them, and what they could see there was not a distant future of plenty, but an immediate future of immiseration. The Luddites were not fools, quite the contrary: they saw exactly what the new machines meant for themselves and their communities, and so they decided to do something about it.

Despite the popular support the Luddites enjoyed in their own communities, and the extent to which machine-breaking remained a common tactic even after the Luddite risings had been repressed, already in the 19th century more optimistic attitudes towards technology were ascendant. Mueller detects some of this optimism in Karl Marx, noting that “there is evidence for a technophilic Marx” (19), yet Mueller pushes back against the common assumption that Marx was a technological determinist. While recognizing that Marx (and Engels) had made some less than generous comments about the Luddites, Mueller emphasizes Marx’s attention to the real struggles of workers against capitalism and notes that “the struggles against machines were the struggles against the society that utilized them” (24, italics in original text). And the frequency with which machines were becoming targets of worker’s ire in the 19th century demonstrates the way in which workers saw the machines not as neutral tools but as instruments of the factory owners’ power. While defenders of mass machinery may point to the abundance such machines create, some figures like William Morris pushed back on these promises of abundance by noting that such machinery sapped any pleasure out of the act of laboring while the abundance was just a share in shoddy goods. In Marx and Morris, as well as in the actual struggles of workers, Mueller points to the importance of technology becoming recognized as a site of political struggle—emphasizing that in worker’s resistance to technology can be found “a more liberatory politics of work and technology” (29).

That the 19th century was home to the most renowned fight against technology, does not mean that these struggles (be they physical or philosophical) ended with the arrival of the 20th century. While much is often made of the “scientific management” of Frederick W. Taylor, less is often said of the ways in which workers resisted this system that turned them into living cogs—and even less is usually said of the strike at the Watertown Arsenal wherein (quite unlike the case of the Luddites) Congress sided with the workers (and their union). Nevertheless, the Taylorist viewpoint that “capitalist technologies like scientific management” were “an objective way to improve productivity and therefore the condition of workers” (35) was a viewpoint shared by a not inconsiderable number of socialists in those years. Within the international left of the early 20th century, debates about the meaning of machinery were heated: some like Karl Kautsky took a deterministic stance that developments in capitalist production methods were paving the way for communism; others like the IWW activist Elizabeth Gurley Flynn cheered the tactic of workers sabotaging their machines; still others like Thorstein Veblen dreamed of a technocratic society overseen by benevolent engineers; various Bolsheviks argued about the deployment of Taylorist techniques in the new Soviet state; and standing at the edge of the fascist abyss Walter Benjamin gestured towards a politics that does not praise speed but searches desperately for an emergency brake.

While the direction of debates about technology in the early 20th century were significantly disrupted by the Second World War (just as they had been upended by the First World War), in the aftermath of Auschwitz and Hiroshima debates about technology and work only intensified. Automation represented a new hope to business owners even as it represented a new threat to workers, as automation could sap the power of agitated workers while centralizing further control in the hands of management. Importantly, automation was not simply accepted by workers, and Mueller notes “on the vanguard of opposing automation were those often marginalized by the official workers’ movement—women and African Americans” (63). Opposition to automation often took the form of “wildcat strikes” with union leaders failing to keep pace with the radicalism and fury of their members. In this period of post-war tumult, left-wing thinkers ranging from Raya Dunayevskaya to Herbert Marcuse to Shulamith Firestone articulated a spectrum of different responses to the promises and perils of automation—yet even as they theorized: workers in mines, factories, and at the docks continued to strike against what the introduction of automation meant for their lives. Simultaneously, automation became a topic of interest, and debate, within the social movements of the time, with automation being viewed by those movements as threat and hope.

Lurking in the background of many of the discussions around automation was the spread of computers. As increasing numbers of people became aware of them, computers quickly conjured both adoration and dread—they were a frequent target of student activists in the 1960s and 1970s, even as elements of the counterculture (such as Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog) were enthusiastic about computers. Businesses were quick to adopt computers, and these machines often accelerated the automation of workplaces (while opening up new types of work to the threat of being automated). Yet the rise of the computer also gave rise to a new sort of figure, “the hacker” whose very technological expertise positioned them to challenge computerized capitalism. Though the “politics of hackers are complicated,” Mueller emphasizes that they are often some of technology’s “most critical users, and they regularly deploy their skills to subvert measures by corporations to rationalize and control computer user behavior. They are often Luddites to the core” (105). Not uniformly uncritical celebrants of technology, many hackers turn their intimate knowledge of computers into a way of knowing where best to strike—even as they champion initiatives such as free software, peer-to-peer sharing, and tools for avoiding surveillance.

Yet as computers have infiltrated nearly every space and moment, it is not only hackers who find themselves regularly interacting with these machines. The omnipresence of computers creates a situation wherein “work seeps into every nook and cranny of human existence via capitalist technologies, accompanied by the erosion of wages and free time” (119) as more and more of our activities become fodder for corporate recommendation algorithms we find ourselves endlessly working for Facebook and Google even as we respond to work emails at 1 a.m. Despite the promises of digital plenty, computing technologies (broadly defined) seem to be giving rise to an increasing sense of frustration, and though there are some who advocate for an anodyne “tech humanism,” it may well be that “the strategy of refusal pursued by the industrial workers of old might be a more promising technique against the depression engines of social media” (122).

Breaking Things at Work concludes with a call for the radical left to “put forth a decelerationist politics: a politics of slowing down change, undermining technological progress, and limiting capital’s rapacity, while developing organization and cultivating militancy” (127-128). Such a politics entails not a rejection of progress, but a critical reexamination of what it is that is actually meant when the word “progress” is bandied about, as too often what progress stands for is “the progress of elites at the expense of the rest of us” (128). Putting forth such a politics does not require creating something entirely new, but rather recognizing that the elements of just such a politics can be seen repeatedly in worker’s movements and social movements.

In putting forth a clear definition of “Luddism,” Mueller highlights that Luddism “emphasizes autonomy” by seeking to put control back into the hands of the people actually doing the work, “views technology not as neutral but as a site of struggle,” “rejects production for production’s sake,” “can generalize” into a strategy for mass action, and is “antagonistic” taking a firm stance in clear opposition to capitalism and capitalist technology. In the increasing frustration with social media, in the growing environmental calls for “degrowth,” and in the cracks showing in the golden calf of technology, the space is opening for a politics that takes up the hammer of Luddism. Recognizing as it does so, that a hammer can be used not just to smash things that need to be broken, a hammer can also be used to build something different.

*

One of the factors that makes Luddism so appealing more than two centuries later is that it is an ideology that still calls out to be developed. The historic Luddites were undoubtedly real people, with real worries, and real thoughts on the tactics that they were deploying—and yet the historic Luddites did not leave any manifestoes or books of their own writing behind. What remains from the Luddites are primarily the letters they sent and snatches of songs in which they were immortalized (which have been helpfully collected in Kevin Binfield’s 2015 Writings of the Luddites). And though one can begin to cobble together a philosophy of technology from reading through those letters, the work of explaining exactly what it is that Luddism means has been a task that has largely fallen to others. Granted, part of what made the Luddites successful in their time was that the mask of General Ludd could be picked up and worn by many individuals, all of whom could claim to be General Ludd (or his representative).

With Breaking Things at Work, Gavin Mueller has crafted a vital contribution to Luddism, and what makes this book especially important is the way in which it furthers Luddism in a variety of ways. On one level, Mueller’s book provides a solid introduction and overview to Luddite thinking and tactics throughout the ages, which makes the book a useful retort to those who act as though the historic Luddites were the only workers who ever dared oppose machinery. Yet Mueller makes it clear from the outset of his book that he is not primarily interested in writing a history, rather his book has a clear political goal as well—he wishes to raise the banner of General Ludd and encourage others to march behind this standard. Thus, Mueller’s book is simultaneously an account of Luddism’s past, while also an appeal for Luddism’s future. And while Mueller provides a thoughtful consideration of many past figures and movements that have dallied with Luddism, his book concludes with a clear articulation of what a present day Luddism might look like. For those who call themselves Luddites, or those who would call themselves Luddites, Mueller provides a historically grounded but present focused account of what it meant, and what it can mean, to be a Luddite.

The clarity with which Mueller defines Luddism in Breaking Things at Work places the book into a genuine debate as to how exactly Luddism should be defined. And this is a debate that Mueller’s book engages with in a particularly provocative way considering how his book is both a scholarly account and an activist manifesto. Writing about the Luddites tends to fall into several camps: works that provide a fairly straightforward historical account of who the original Luddites were and what they literally did (this genre includes works like E.P. Thompson’s Making of the English Working Class, and Kevin Binfield’s Writings of the Luddites); works that treat Luddism as an idea and a philosophy that is not exclusive to the historic Luddites (this genre includes works like Nicols Fox’s Against the Machine, and Matt Tierney’s Dismantlings), works that emphasize that the tactic of machine-breaking was not practiced exclusively by the Luddites (this genre includes works like Eric Hobsbawm and Geogre Rudé’s Captain Swing, and David Noble’s Progress Without People), and works that draw lines (good or bad) from Luddism to later activist practices (this genre includes approving works like Kirkpatrick Sale’s Rebels Against the Future, and disapproving works like Steven Jones’s Against Technology). Mueller’s Breaking Things at Work does not fit neatly into any single one of those categories: the Marxist analysis makes the book pair nicely with Thompson’s book, the engagement with radical theorists makes the book pair nicely with Tierney’s book, the treatment of machine-breaking as a common tactic makes the book pair nicely with Noble’s book, and the call to arms places the book into debate with books by the likes of Sale and Jones.

All of which is to say, the meaning of Luddism remains contested terrain. And even though many of technology’s celebrants remain content to use Luddite as an insult, those who would proudly wear the mask of General Ludd are not themselves all in agreement about exactly what this means.

Mueller has written a wonderfully provocative book, and it is one in which he does not attempt to hide his own opinion behind two dozen carefully composed distractions. Instead, Mueller is quite clear “to be a good Marxist is to also be a Luddite” (5), and this is a point that leads directly into his goal of turning Marxists into Luddites and making Marxists out of those who are critical of technology. And in his engagement with Marx, Mueller tangles with the perceptions of Marx as technophilic, engages with a variety of Marxist thinkers who fall into a range of camps, all while trying “to be faithful to Marxism’s heretical side, its unofficial channels and para-academic spaces” (vii). And all the while Mueller endeavors to keep his book grounded as a contribution to real struggles around technology in the world today. Considering Mueller’s clear statement of his own position it is likely that some will level their critiques at the book’s Marxism, and still others might critique the book for not being sufficiently Marxist. And as is always the case with books that situate their critique within a particular radical tradition it seems inevitable that some will wonder why their favorite thinker is not included (or does not receive more attention), even as others will wonder why other branches from the tree of the radical left are missing. (Mueller does not spend much time on anarchist thinkers).

Overall, the question of whether this book will turn its Marxist readers into Luddites, and its technologically critical readers into Marxists is one that can only be answered by each reader themselves. For what Mueller’s book presents is an argument, and the way in which a reader nods along or argues back is likely to be heavily influenced by the way they personally define Luddism. And Mueller is not the first to try to rally people beneath the Luddite’s standard.

In 1990, Chellis Glendinning published her “Notes Towards a Neo-Luddite Manifesto” in the pages of the Utne Reader. Furiously lamenting the ways in which societies were struggling under the onslaught of new technologies, her manifesto was a call to take up oppositional arms. While taking on the mantle of “Neo-Luddite,” the manifesto articulated a Luddism (or Neo-Luddism) that was defined by three principles: “1. Neo-Luddites are not anti-technology,” “2. All technologies are political,” and “3. The personal view of technology is dangerously limited.” Based on these principles, Glendinning’s manifesto laid out a program that included the dismantling of a range of “destructive” technologies (including genetic engineering technologies and computer technologies), pushed for the search for “new technological forms” that would be “for the benefit of life on Earth,” and this in turn was couched in a call for “Western technological societies” to develop a “life-enhancing worldview.” The manifesto drew on the technological criticism of Lewis Mumford, on Langdon Winner’s call for “epistemological Luddism,” and on the uncompromising stance towards technologies deemed destructive typified by Jerry Mander’s Four Arguments For the Elimination of Television.

The Neo-Luddites are more noteworthy for their attempt to reclaim and redefine Luddism than they are for their success in actually creating a movement. Indeed, the lasting legacy of Neo-Luddism is not that of a vital social movement that fought for (and continues to fight for) the principles Glendinning put forth, but instead about half a bookshelf worth of books with “Neo-Luddite” somewhere in their title. There are certainly critiques to be leveled at the Neo-Luddites, but when revisiting Glendinning’s manifesto it is also worth placing it in the moment at which it emerged. The backdrop for Breaking Things at Work is one in which most readers will be accustomed to seemingly omnipresent computing technologies, climate exacerbated disasters, and a world in which the wealth of tech billionaires grows massively by the minute. By contrast, the backdrop for Glendinning’s manifesto was a moment in which personal computers had not yet achieved ubiquity (no one was carrying the Internet around in their pocket), climate change still seemed like a distant threat, and Mark Zuckerberg was still a child. It is impossible to say whether or not Glendinning’s manifesto, had it been heeded, could have prevented us from getting into our present morass, but preventing us from winding up where we are now certainly seems to have been one of Glendinning’s goals. At the very least, Glendinning and the Neo-Luddites (as well as the thinkers upon whom they drew) are a reminder that the spirit of General Ludd was circulating before you could Google “Luddism.”

There are many parallels between the stances outlined by Glendinning and those outlined by Mueller. Though it seems that the key space of conflict between the two is around the question of dismantling. Glendinning and the Neo-Luddites were not subtle in their calls for dismantling certain technologies, whereas Mueller is considerably more nuanced in this respect. Here attempts to define Luddism find themselves butting against the degree to which Luddism is destined to always be associated (for better or worse) with the actual breaking of machines. The naming of entire classes of technology that need to be dismantled may appear like indiscriminate smashing, while calls for careful reevaluation of technologies may appear more like thoughtful disassembly. Yet the underlying question for Luddism remains: are certain technologies irredeemable? Are there technologies that we can remake in a different image, or will those technologies only reshape us in their own image? And if the answer is that these technologies cannot be reshaped, than are there some technologies that we need to break before they can finish breaking us, even if we often find ourselves enjoying some of the benefits of those technologies?

Writing of the reactions from a range of 1960s social movements to the technological changes they were seeing playing out, Mueller notes that the particular technology that evoked “both fear and fascination” was none other than “the computer” (91). This point leads into what is perhaps the most troubling and challenging element of Mueller’s account, as he goes on to argue that hackers and some of their projects (like free software) fit within the legacy of Luddism. I imagine that many hackers will not be too pleased to see themselves described as Luddites, just as I imagine that many self-professed Luddites will scoff at the idea that using bitcoins to buy drugs on the dark web is a Luddite pursuit. Yet the idea that those most familiar with a technology may know exactly where to strike certainly has some noteworthy resonances with the historic Luddites.

And yet the matter of hackers and “high tech Luddism” raises a much broader question, one that the left has been trying to answer for quite some time, and perhaps the key question for any attempt to formulate a Luddite politics in this moment: what are we to make of the computer? Is the computer (and computing technologies, broadly defined) the offspring of the military-industrial-academic complex with logics of control, surveillance, and dominance so deeply ingrained that it ultimately winds up bending all users to that logic? Despite those origins, are computing technologies something which can be seized upon to allow us to reconfigure ourselves into new sorts of beings (cyborgs, perhaps) to break out of the very categories that capitalism tries to sort us into? Have computers fundamentally altered what it means to be human? Is the computer (and the Internet) simply something that has become so big and so widespread that the best we can hope for is to increase our knowledge of it so that we can perform sabotage strikes while playing in the dark corners? Are computers the “master’s tools”?

Considering that computer technologies were amongst those that the Neo-Luddites called to be dismantled, it seems pretty clear where they came down on this question. Yet contemporary discussions on the left around computers, a discussion in which Breaking Things at Work is certainly making an intervention, is quite a bit more divided as to what is to be done with and about computers. At several junctures in his book, Mueller notes that attitudes of technological optimism are starting to break down, yet if you survey the books dealing with technology published by the left-wing publisher Verso Books (which is the publisher of Breaking Things at Work) it is clear that a hopeful attitude towards technology is still present in much of the left. Certainly, there are arguments about the way that tech companies are screwing things up, commentary on the environmental costs of the hunger for high-tech gadgets, and paeans for how the Internet could be different—but it often feels that leftist commentaries blast Silicon Valley for what it has done to computers and the Internet so that the readers of such books can continue believing that the problems with computers and the Internet is what capitalism has done to them rather than suggest that these are capitalist tools through and through.

Is the problem that the train we are on is taking us somewhere we don’t want to go, so we need to slow down so that we can switch tracks? Or is the problem the train itself and we need to hit the emergency brake so that we can get off? To those who have grown accustomed to the comforts of being on board the train, the idea of getting off of it might be a scary thought, it might feel preferable to fight for a more equitable distribution of resources aboard the train, or to fight to seize control of the engine car. Besides, the idea of actually getting off the train seems like little more than a fantasy—it will be hard enough just to get it to reduce its speed. Yet the question remains as to whether the problem is the direction we’re going in, or if the problem is the direction we’re going in and the technology that is taking us in that direction.

Here it is essential to return to an important fact about the historic Luddites: they were waging their campaign against the introduction of machinery in the moment of those machines’ newness. The machines they attacked had not yet become common, and the moment of negotiation as to what these machines would mean and how they would be deployed was still in flux. When technologies are new they provide a fertile space for resistance, in their moment of freshness they have not yet become taken for granted, previous lifeways have not been forgotten, the skills that were necessary prior to the introduction of the new machine remain vital, and the broader society has not become pleasantly accustomed to their share of machine generated plenitude. Unfortunately, once a technology has become fully incorporated into a workplace (or a society) resistance becomes more and more challenging. While Mueller evocatively captures the long history of workers resisting the introduction of new technologies, these cases show a consistent tendency for this resistance to take place most strongly at the point of the new technology’s introduction. The major challenge becomes what to do when the technology has ceased being new, and when the reliance on that technology has become so total that it becomes almost impossible to imagine turning it off.

After all, it’s easy to say that “computers are the problem” but at this point it’s easier to imagine the end of capitalism than it is to imagine the end of computers. And besides, many of those who would be quite happy to see capitalism come to an end quite like their computerized doodads and would be distressed if they couldn’t scroll social media on the subway, stream music, go shopping at 2 a.m., play video games, have video calls with distant family, or write overly lengthy book reviews and then post them online. One of the major challenges for technological criticism today is the simple fact that the critics are also reliant on these gadgets, and many of the critics quite like some things about some of those gadgets. In this technological climate, where the idea of truly banishing certain technologies seems fantastical, feelings of dissatisfaction often wind up getting channeled in the direction of appeals to personal responsibility. As though an individual deciding that they will abstain from going on social media on the weekend will somehow be a sufficient response to social media eating the world. This is the way in which a massive social problem winds up being reduced to telling people that they really just need to turn off notifications on their phones.

What makes Breaking Things at Work, and its definition of Luddism, vital is the way in which Mueller eschews such appeals to minor lifestyle tweaks. As Mueller makes clear the significance of the Luddites is not that they broke machines, but that they saw machines as a site of political struggle, and the thing we need to learn from them today is that machinery still must be a site of political struggle. Turning off notifications, following people with different politics, trying to spend a day a week offline—while these actions can be useful on an individual level, they are not a sufficient response to the ways that technology challenges us today. In a moment wherein so many of the proclamations from Silicon Valley are treated as though they are inevitable, Luddism functions as a powerful retort and as a useful reminder that the people most invested in the belief that you cannot resist capitalist technologies are the people who are most terrified that people might resist those technologies.

In one of the most infamous of the surviving Luddite letters, “the General of the Army of Redressers,” Ned Ludd writes: “We will never lay down our Arms. The House of Commons passes an Act to put down all Machinery hurtful to Commonality, and repeal that to hang Frame Breakers. But We. We petition no more that won’t do fighting must.” These were militant words from a militant movement, but the idea that there is such a thing as “Machinery hurtful to Commonality” and that such machinery needs to be opposed remains clear two hundred years later.

There is a specter haunting technological society—the specter of Luddism. And as Mueller makes clear in Breaking Things at Work that specter is becoming more corporeal by the moment.

_____

Zachary Loeb earned his MSIS from the University of Texas at Austin, an MA from the Media, Culture, and Communications department at NYU, and is currently a PhD candidate in the History and Sociology of Science department at the University of Pennsylvania. Loeb works at the intersection of the history of technology and disaster studies, and his research focusses on the ways that complex technological systems amplify risk, as well as the history of technological doom-saying. He is working on a dissertation on Y2K. Loeb writes at the blog Librarianshipwreck, and is a frequent contributor to The b2o Review Digital Studies section.

_____

Works Cited

- Binfield, Kevin, ed. 2015. Writings of the Luddites. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Glendenning, Chellis. 1990. “Notes toward a Neo-Luddite Manifesto.” Utne Reader.