After Jameson

Christian Thorne

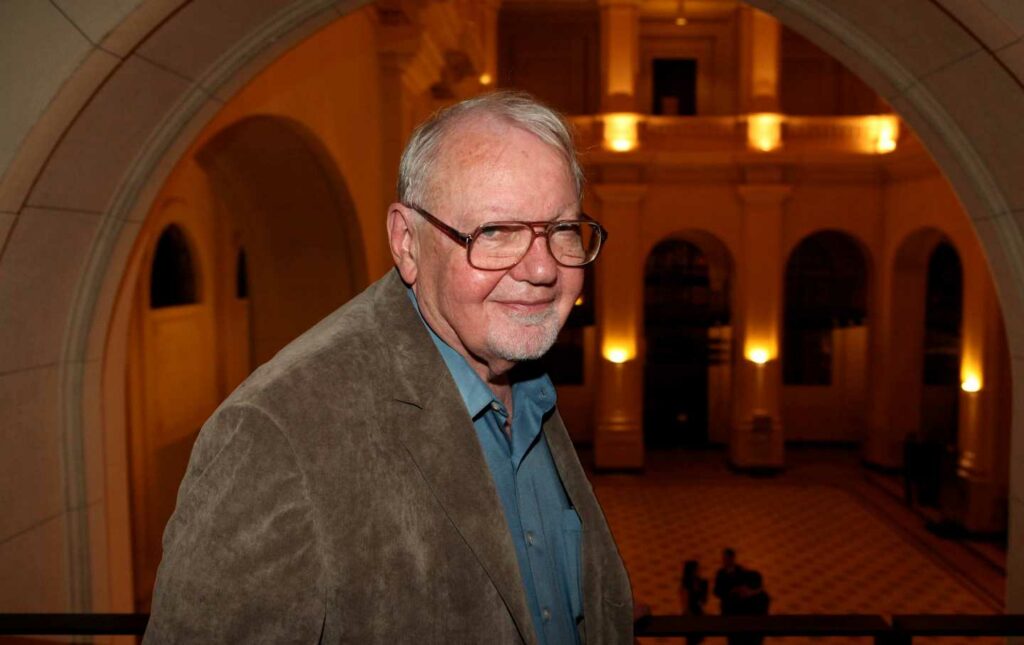

Fredric Jameson, who was a member of the boundary 2 editorial board for several years, died on September 22. One wishes to know what we have lost in his passing, and to know, too, something about what comes next, about who to read once we have leafed our way through his Nachlass; about what we had been counting on Jameson to do on our behalf that we will have to figure out how to do ourselves now that he is gone. Did Jameson leave a to-do list? Such questions are, in this case, unusually hard to answer, and this difficulty has something to do with the character of Jameson’s own thought, which, after all, had a lot to say about endings and aftermaths. His most quoted, if often misattributed, sentence concerns What Ends and What Obstinately Refuses to End: “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism.” He was drawn at an early date to the term “postmodern”—not his coinage, of course, but sometimes treated as his contagious invention—which communicates the paradoxical claim that something can come after the definitionally and self-regeneratingly new. The word that he and others came up with for the book series they started at Duke went “postmodernism” one better. “Postcontemporary Interventions” they called it—whatever is later than now, which presumably just means “the future,” as in: interventions from the future. Or for it. One chapter in Jameson’s Postmodernism book offers to identify “Utopianism after the End of Utopias.” The corresponding chapter in The Antinomies of Realism announces a “Realism after Realism.” To this we should add a certain Jamesonian penchant for calling things “late”—late capitalism, late Marxism, late modernism—as well as his repeated claim that there are entire genres that we “no longer know how to read”: literary utopias, Renaissance allegories. Anything we would want to say about the end of this particular thinking life will jostle uncomfortably against that life’s many observations about what it means to perceive a terminus (or a survival or a novum).

These several threads are best bundled under the rubric of “periodization,” which was itself one of Jameson’s abiding preoccupations. There was an interval of some twenty years when he seemed unable to finish an essay without introducing his 2 x 3 scheme of literary-and-economic periodization: realism, modernism, postmodernism; national capitalism, monopoly capitalism, late capitalism. (The only thing that changed over that span was that Giovanni Arrighi got swapped in for Ernst Mandel, as the argument’s catch-all citation for economic history.) The tributes and callings-after that have appeared since Jameson’s death themselves all flirt with periodizing claims. It is hard not to feel that theory has, in his person, died another of its serial deaths. Terry Eagleton’s After Theory was published all the way back in 2003; Jameson outlived that “after” by a handsome one-and-twenty. Along the way, in 2015, Rita Felski tried to bury the “critical” part of “critical theory,” with Jameson as its avatar. Jameson himself, in a book published after his death, said that theory came to an end with the election of François Mitterand in 1981, though anyone who has read 1994’s Seeds of Time or 2005’s Archaeologies of the Future knows that this can’t be true.

But those multiple and contending dates are enough to remind a person of one of Jameson’s most consequential insights into periodization: that periods are not facts, not realia there to be discovered in the historical record; that they have to be posited and can always be posited otherwise. Exactly when do you think “the years of theory” ended (if, indeed, you do think they’ve ended)? When the University of Minnesota retired its Theory and History of Literature series in 1998? When Edward Said died in 2003? When Derrida died in 2004? When dissident thought got routinized in dozens upon dozens of tenure-track positions across North America, codified in C.V.-ready certificate programs and European prizes? Or when that one generation of theorists retired and the English departments decided they didn’t need replacing? Jameson was always quick to concede that the periods to which he dedicated some eight published books were devices or even contrivances—the mind’s way of organizing miscellaneous historical materials to particular (and nameable) ends. The history journals are crammed by the hundredfold with articles naming this or that previously unknown revolution—the Second Scientific, the Third Industrial, the antibiotic, the cybernetic, the “civil rights revolution”—all of them countered by an equal number of essays insisting that x turning-point in history “wasn’t really a revolution,” that 1789 (or 1917 or the fall of the Roman Empire) didn’t change anything we would care to call fundamental. Jameson always held to the entirely commonsensical position that in any historical conjuncture, some things will have withered away or been replaced and other things will have persisted, and he enjoyed rolling his eyes over the historians who argued as though the archive could tell you which it was really. The members of the AHA stand in opposite wings of the conference hotel yelling the words “Continuity!” and “Rupture!” across the bewildered lobby. This aspect of Jameson is most fully on display in A Singular Modernity, which argues that “modernity” is neither a date nor a datum; that it is a concept, rather; or, no, not a concept, but a narrative template, a story form. He then sets out to enumerate the features of the modernity narrative, as though it were just one more entry in the list of recognized genres, alongside the historical romance and the legal thriller, before scanning the ranks of theorists in order to show that they were all actually telling the kind of Big Stories about History that postmodernism officially disavowed.

Those narratives were, of course, many and varied. A genre spins many stories—and not just one. The next point to grasp, then, is that Jameson did not just collect multiple modernity narratives—Heidegger’s and Foucault’s and Weber’s and de Man’s. His own efforts at periodization were themselves multiple. Even the most ardent readers of Jameson were slow to realize that he thought of most of his writing as so many volumes in One Big Book, a Hegelian world history of narrative types that we have come to know as The Poetics of Social Forms. That title itself went through stages, creeping into print in an early ‘80s footnote (“I discuss x in my forthcoming…); slowly worming its way onto the copyright pages of late-career monographs, where it hugged itself into the fastness of eight-point font (“The present book constitutes the theoretical section of the antepenultimate volume of….”); before finally breaking forth into reference-book entries and scholarly reviews and Verso promotional copy. The second surprise, after the initial awe of watching this narratological epic accrete surreptitiously and out-of-sequence over the course of forty years, arrives with the realization that Jameson was not in its pages telling the story that you might have thought he was always telling: from realism to modernism to postmodernism. Those stages were still there, each in a virtual volume, plus two more—a volume on post-capitalist narrative and a presumably unfinished volume on pre-capitalist narrative—but his characterization of those familiar literary-historical periods had begun to shift and multiply.

Whenever Jameson inserted his threefold scheme into an essay on the fly, in that one compressed paragraph that he must have composed in fifteen or twenty variants, his position was always fundamentally Lukacsian: 1) The work of literary realism was to make complex social systems experientially intelligible. 2) Modernist literature pulled the plug on this intelligibility, letting the socius fog back over—or, if you prefer, faithfully replicating the opacity of everyday life—while offering as compensation a set of writerly and stylistic experiments that the sensitive reader would experience as so many “intensities.” 3) Postmodernism then neutralized these intensities in turn, withdrawing into flat affect and mimeographed irony while allowing opacity to spiral into full-blown spatial and temporal disorientation. Anyone who suspected that Jameson’s Marxism was finally a tad vulgar could see that he had, for an instant, vindicated Adorno and Brecht at the expense of Lukacs—reprieving modernism from its banishment by the Party—only then to reinstate the Lukacsian verdict against the newer art of the 1970s and ‘80s.

Except this isn’t at all what we read in The Poetics of Social Forms, which went out of its way to scramble his beloved three-stage progression. The difference is clearest in the cycle’s two volumes on realism: The Political Unconscious, which traces the survival of the pre-modern romance across the entire body of nineteenth-century realist fiction (a fiction whose realism accordingly comes to seem less steady); and The Antinomies of Realism, which describes the swelling of literary affect across the same decades and in the same canon of novels. Realism thus preserves the storytelling impulses of its predecessor and rival (the magically heroic adventure story), while also undertaking in advance the very production of “intensities” that Jameson elsewhere told us was the work, distinctively, of modernism. What Jameson did not write is the one volume you might have expected from his hand—that neo-Lukacsian tract in which he enumerated all the vanished techniques of Balzaco-Dickensian cognitive mapping. The closest thing we have to that missing disquisition is his short book on Chandler, The Detections of Totality, which explains how one modernist-era writer was able in some fresh way to do the very thing that modernist writers were supposedly unable to do any more.

Jameson’s writings are full of phase shifts of this kind, which we can conceptualize in a few different ways. The easiest approach would be to say that Jameson was unusually committed to the Raymond-Williamsite categories of the “residual” and the “emergent”: We must make the effort to discern historical periods, while also insisting that periods are never clean and discrete, that they all come before us bearing contamination and articulation and overlap. At the same time, Jameson’s variously romantic and modernist realisms are clearly dialectical figures, since one of the theorist’s more obviously Hegelian tasks will be to trace the incubation of a new mode in whatever seemingly inimical form preceded it—and then to trace its survival, as Aufhebung, even after its apparent obsolescence. If, meanwhile, you prefer your dialectics more negative than this, you could get away with saying nothing more than that Jameson seemed to prefer realism when it was least itself—and that he consistently looked to other literary modes to do the realist work that realism could no longer convincingly do.

The issue, for now, is this: Measuring Jameson’s achievement (and our loss) requires us to periodize, and it was Jameson himself who did more than any other theorist to insist that periodization was both a) necessary, unavoidable; and b) a complex, non-empirical operation. So let’s reach back two paragraphs and say again: Periods are not realia; they have to be posited. Once you’ve grasped that point, it should be easy enough to make it, iteratively, for pretty much all of Jameson’s other master concepts. He was committed to periodization, but insisted over and over again that all periods were devices or mental constructs. Similarly, he was committed to thinking in terms of totality—to detailing what an anti-totalitarian thinking gives up when it tries to do without the very category of totality—while making it clear even so that the totality cannot be known, that all totality-talk is thus a conceit and model and more or less ingenious attempt at Darstellung, at representing a hyper-object about which we can properly say nothing. (Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must tell stories.) This makes it harder than one might have thought to distinguish Jameson from the post-structuralists with whom he kept company and who are typically regarded as his adversaries. For Jameson was as much an anti-foundationalist as any other left-wing Francophile writing in the ‘70s and ‘80s: a philosophical skeptic and resolute anti-positivist, careful not to get caught making strong knowledge claims, quick to point out that what one had all along thought to be things were actually fictions or arbitrary categories or discursive contrivances. His erudition was legendary: It was Jameson who, in reply to some visiting Spinozist, would have remarks at the ready about Jan de Witt and the fate of seventeenth-century Dutch republicanism; Jameson, too, who would sit up front at the Pacific historian’s sparsely attended talk and toss off questions about modernist architecture in Hawaii. And yet Jameson’s general conception of history was itself more or less skeptical. For to say that “history is what hurts” is to ask us to think of history above all as failure and limitation—our failure and our limitation—as the world’s recalcitrance, its hard check on our desires. This is a materialism, no doubt, but of some traumatic and non-cognizable kind, a materialism of the Real, in which history announces itself only in the occasional and crushing realization that we had history all wrong.

What was it, then, that distinguished Jameson from any old literary Lacanian? We can come at the matter this way. Your run-of-the-mill anti-foundationalist typically makes two moves in quick succession: First, they declare all grand narratives (or what have you) to be fictions; and then they withdraw belief from all such fictions, retreating into a wary and disabused agnosticism, embarrassed by their former gullibility. It is this stance of negation that Jameson, in this respect entirely unlike Adorno, dispensed with. Enthusiastic about fiction in all its forms, he set out to catalog all the grand narratives; and he proved deft at reconstructing the Big Stories about History that subtend even those philosophical systems that thought they could do without them; and, crucially, he devised two or three Big Stories of his own, to place alongside these others, constructions among constructions. This stance, of course, separated him from more than just the skeptics. If even Marxist readers have sometimes struggled to get the hang of Jameson, then this is surely because he extended his attitude of affirmation even to historical materialism’s most fearsome bogeymen, the things you might have thought that no Marxist could make friends with: ideology, say, which Jameson told us was just the other side of utopianism, and even reification, without which, he concluded, no politics was possible. (The lesson of a lifetime spent thinking about allegory boils down to: If you want to fight it, you have to reify it.) The post-critical types who have nominated him the paranoid taskmaster of Kritik have to that extent got him exactly wrong. Hegelianism is that peculiar point of view from which you can look out over a field of contention and see that everyone is right.

But then what about postmodernism, which is, after all, the word with which Jameson’s name will permanently be linked? Did he affirm that? We would do well to remind ourselves here of a remark he made frequently around 1990, at the height of the postmodernism debates, which is that he had grown weary of interlocutors asking him whether he liked postmodernism. Did he think it was a good thing? Or was he, when all was said and done, calling for the revival of a Left modernism? Postmodernism, he said, was not the sort of thing that could be either celebrated or condemned. It was—and here we can refine our formulation a bit—the bad thing that had to be affirmed. This position has everything to do with Jameson’s implicitly Hegelian ethics—with Hegel’s resolve not to be alienated, with his warnings against the romance of marginality and the heroics of total refusal; and this, in turn, leads directly to a Hegelian political orientation, which holds that any future we might build will have to go by way of the dominant. The better society will not be a fresh start; we will get there only by traversing the most powerful institutions, the most public discourses, the most official culture and by transposing these where possible. Postmodernism might mark the epochal victory of consumerism and media society on the terrain of art and inward experience—that, too, was Jameson’s claim—but the task in front of is nonetheless to figure out what else can be built with its materials.

It becomes possible to wonder, at this point, whether Jameson wasn’t himself a postmodernist—not just a student of postmodernism, but a postmodern writer in his own right, to be ranked alongside Ballard and Barthelme and Calvino. The jumbling of high and low? When you are done reading his article on Proust, you can queue up his essay on The Godfather and Jaws—or on Spenser or on spaceships or on Conrad or on a Stephen King story. Flat affect? Has ever a Marxist written with more equanimity, without the tones of indignant sarcasm and subaltern pathos that mark the entire tradition from the Communist Manifesto onwards? The triumph of the image and the canceling of the referent? It was Jameson who pointed out that Doctorow had given us, in Ragtime, a historical novel in which history seemed blocked and unknowable, in which “real history” had given way to mirages and animatronics, a “hologram” of the past that differed from the fictions of Walter Scott in that it wanted you to know that it was a hologram. But then didn’t Jameson re-do Marxism to Doctorow’s specifications, preserving all the old historical materialist schemes while confessing upfront that these were and always had been stories? Wasn’t it Jameson who gave us Marxism with a buried, never appearing, thoroughly mediatized historical referent?

And with that, it becomes possible to explain why it is so hard to say what comes after Jameson or where his leaving leaves us. His thinking was so intertwined with postmodernism that to imagine a time after Jameson is to imagine a time after postmodernism. His passing thus compels us to ask: Are we still postmodern? Or are we now after postmodernism? And the answers to those questions are surprisingly uncertain. That ours is no longer the moment of Robert Venturi and John Barth and Terry Riley seems clear enough. And yet doesn’t the Berlusconi-Trump era of Western politics strike you sometimes as Baudrillard’s bad joke? Aren’t memes an intensified and grassroots postmodernism for the Internet age? Brian de Palma may not be making movies anymore, but Quentin Tarantino sure is. Should one therefore propose the term “late postmodernism” and see if it sticks? But then what do we make of the rise of “world-building,” as both a term and a narrative practice (in blockbuster film and video games and long-form television), so different from the discombobulated worldlessness of high postmodernism? Or what do we make of radical philosophy’s ontological turn, which has traded the epistemological skepticism of the post-structuralist decades for a downright neo-scholastic metaphysics? Or again, if we conclude that postmodernism is or was art in the age of neoliberalism, then what do we make of the breakup of the neoliberal consensus? Equally, though, if we are really beyond postmodernism—if we have passed through it and out the other side—shouldn’t we be able to describe the present and maybe even name it and then say in some detail how the 2020s are not like the 1980s? Are we still postmodern? If that question has gone largely unasked—if the very formulation is perhaps a bit embarrassing—this is precisely the sign of the Jamesonian intelligence that has gone missing. The good thing is not yet here. But can we name at least the new bad thing and say how we plan to affirm it?