This article is part of the b2o: an online journal Special Issue “The Gordian Knot of Finance”.

The Modern Money Tangle: An Introduction

Martijn Konings

It is increasingly evident that the existing economic policy paradigm is a recipe for ongoing economic stagnation, political polarization, and ecological degradation. But this growing awareness often seems peculiarly inconsequential, incapable of driving even minor shifts in the most conspicuously harmful policy settings, including governments’ enormous subsidies for fossil fuel extraction and the near-perfect exemption of extreme private wealth from taxation. Even as electoral systems have become almost as volatile as the stock market, it seems that, when it comes to economic policy, the political center holds, inexplicably.

We tend to call that paradigm “neoliberalism”. The epithet was first used by academics. But, as during the decade following the Global Financial Crisis wider communities of observers found themselves increasingly puzzled by the immunity of economic policy to feedback from social and ecological systems, the label became used more widely (Slobodian 2018, Monbiot and Hutchinson 2024). The problem, by this account, consists in politicians’ and policymakers’ unexamined belief in an expanded role for market mechanisms as the obvious solution to any and all social problems. Moreover, that erroneous belief is self-reinforcing, as the persistence or worsening of social problems is only ever taken to mean that not enough market efficiency has yet been applied.

In the social sciences themselves, neoliberalism has become a contested concept. A general definition – neoliberalism as the reformulation of a classic liberalism in response to the rise and crisis of Keynesianism – is unlikely to encounter many objections. But the critical force of the neoliberalism concept is premised on a more specific claim – namely, the ability to capture the diminishing role of the state and the expansion of the market. It is not at all clear, however, that such a shift in society’s center of gravity, from public to private, has taken place. The very period during which the concept of neoliberalism established itself as a common descriptor was also the era of “quantitative easing” (asset purchases by the central bank) and “macroprudential regulation” (concerning itself not just with the health of individual firms but with macro-level stability) during which Western governments took on an unprecedented level of responsibility for maintaining the balance sheets of large financial institutions (Tooze 2018, Petrou 2021). Entirely contrary to what the neoliberal schema would suggest, the functioning of government institutions has become deeply entangled with the expanded reproduction of private wealth (Konings 2025).

Supported by the significant historical and conceptual nuance that recent scholarship has provided, some have argued that the neoliberalism concept can accommodate such developments. But such qualifications undercut the critical thrust of neoliberalism as an off-the-shelf diagnosis of our current predicament. Others have gone further in questioning the suitability of traditional categories of state and market for capturing structures of power and exploitation that appear simultaneously archaic and futuristic. Neoliberalism, from such a perspective, may simply have buckled under the weight of its own contradictions, and we are now seeing a transition to a very different kind of society – neo-feudalism or technofeudalism (Dean 2020, Varoufakis 2024). Such takes align with the self-image of many Silicon Valley billionaires, who often see themselves less as capitalist entrepreneurs than as the founders of new dynastic bloodlines. But treating such heroic or nihilistic self-stylings as reliable guides to current transformations rather than publicly lived mental health struggles may well be a symptom of what Stathis Gourgouris (2019: 144) understands as social theory’s own “monarchical desire”.

A more helpful angle has been advanced by Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), a perspective that understands economic value as a public construct and found considerable traction by pointing out that such public capacities for value creation had been appropriated by the property-owning class (Wray 2015, Kelton 2020). Taking a leaf from the Marxist book of dialectical historical change, MMT authors propose liberating the machinery of public value creation from the pernicious regime of property relations that it has been made to serve and instead to press it into serving “the birth of the people’s economy”, in the words of Stephanie Kelton (2020). If governments can afford to bail out banks, they can fund programs with actual social value.

MMT precursor Abba Lerner (1943, 1947) viewed his perspective on money as a public token as nothing more than a rigorous statement of the assumptions underpinning Keynes’ General Theory. Keynes himself had tried to make his work acceptable to establishment opinion by concentrating primarily on the role of fiscal policy, leaving the overarching financial structure of the capitalist economy go unquestioned. Even during the heyday of Keynesian hegemony, attempts to wield the public purse were always constrained by the fact that control over monetary policy settings was firmly in the hands of central banks (Major 2014, Feinig 2022). That was a key institutional precondition for the rise of neoliberal inflation targeting. But the absurdity of putting monetary decision-making beyond democratic control became fully evident following the Global Financial Crisis, when central banks made permanent an extensive range of subsidies and guarantees for the holders of financial assets, while governments tightened the public purse strings by cutting social programs.

In this context, arguments that had long been dismissed as crank theory were able to bypass the censure of mainstream economics and find purchase in the public sphere. The vicious response of mainstream economics to the popularity of MMT has done more to underscore than to refute the salience of its provocation – that there exist no actual economic reasons why we can’t repurpose the institutions of the bailout state, away from the gratuitous subsidization of private wealth accumulation and towards shared prosperity.

Finance, MMT understands, holds no secret: it’s just a ledger of society’s transactions and commitments. And if these records are in principle as transparent as any other system of accounts, then what is there to prevent the public and its representatives from taking charge and correcting the perverse misallocations embedded in the current system? According to MMT, the main obstacle here is the flawed, arch-neoliberal idea that governments, like private households, need to “balance the books”. Politicians who operate under the pernicious influence of neoliberal ideology do not recognize that governments are sovereign institutions issuing their own currency and are not subject to the same discipline as households. Adding insult to injury, the principle of public austerity is always readily suspended when banks need bailouts – and invariably reinstated again once the danger of system-level meltdown has passed.

MMT has adopted a very literal reading of neoliberalism, imagining that the force of its ideological obfuscations is the main obstacle to repurposing the mechanisms of quantitative easing for the advancement of the people. In reality, the problem runs deeper. The public underwriting of private balance sheets has a long history. From the mid-twentieth century it served as a key instrument for governments to manage the contradictions of welfare capitalism. During the 1970s, neoliberal ideas of fiscal and monetary austerity became influential not because of their ideological strength, but because they provided a way to manage the inflationary pressure produced by risk socialization. That permitted the routinization of bailout and backstop policies, which culminated in the intravenous liquidity drip-feed that large banks enjoy at present.

That arrangement also has deeper social and political roots than it is typically credited with. Government subsidization of asset values is a major factor responsible for the rise of the “1%”, but it has also underpinned a broader reconstruction of middle-class politics, away from wage expectations to capital gains (Adkins, Cooper and Konings 2020). The nineties represented the high point of this asset-focused middle-class politics, when rising home and stock prices delivered benefits widely enough to give credence to the promise of inclusive wealth.

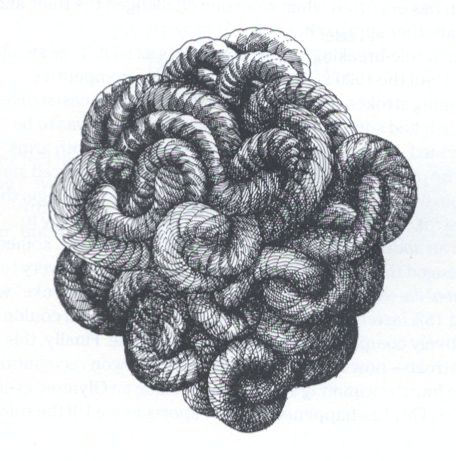

The trickle-down effect has now come to a halt, but that fact does not by itself undo the ideological or institutional structure of the backstop state. The allocation of public resources has become intertwined with the private wealth accumulation in an endless number of ways that are not easily unwound. The idea that governments can do things themselves, without having to put in place complex financing constructions to mobilize private capital and incentivize the doing of said thing by others, has become so incomprehensible in the bourgeois public sphere that there simply no longer exists a straightforward channel for translating social priorities into public spending priorities. What binds the machinery of policymaking to the power of finance is not a set of discrete ties but rather something akin to a Gordian knot.

How to undo, loosen, transform, or bypass that knot? The recent past offers some clues. Since the Covid crisis, modern money has powerfully expressed both its public and its private character. When emergency struck, governments were instantly capable of doing all the things that politicians and experts routinely advise are just not possible. By expanding the safety net beyond the financial too-big-to-fail establishment, they orchestrated a “quantitative easing for the people”, in the words of Frances Coppola (2019). The world’s most powerful central banker, Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell, conceded that there were no real technical limits to the possibility of getting money in the hands of people who needed it (Pelley 2020). Almost overnight, MMT went from indie darling to mainstream pop star. “Is this what winning looks like?”, the New York Times wondered (Smialek 2022). Many declared the end of the neoliberal model.

But before too long, inflation surged, and discourses insisting on strict limits to the use of public money and credit returned to prominence. The discipline thus meted out has been extremely uneven. Central banks across the world have increased interest rates to slow down growth and employment, but for bankers and asset owners the edifice of quantitative easing and liquidity support remains firmly locked in place. Treasuries have similarly tightened the purse strings, swiftly undoing the broadened financial safety nets and undertaking deep cuts in social programs and public education even as they continue to increase spending on the military and corporate tax breaks.

MMTers and other progressives have not failed to call out the hypocrisy, and neoliberal nostrums about the importance of balanced budgets no longer enjoy the same intellectual authority that they once did. But it often seems as if that hardly matters – that the sheer exhaustion of neoliberalism as an intellectual paradigm merely serves to make a mockery of the idea that policy could change in a material way. We can all see that the emperor is not wearing anything, and yet we’re in the midst of a powerful restoration of economic orthodoxy, relentlessly socializing the risk of the largest players while inflicting tight monetary and fiscal policy settings on the rest of the population.

MMTers have allied with other heterodox economists to rebut mainstream arguments for deflationary policy (Weber and Wasner 2023). Inflationary pressures, they argue, had their origins in specific events such as supply-chain disruptions, and should be addressed by targeting those sources – not by carpet-bombing the economic system at large. Such arguments invoke a long history of Keynesian supply-side thinking that aims to undercut inflationary pressures in ways that do not require the central bank or the treasury to deploy their crude instruments of general deflation. The last time such a progressive supply-side agenda had made waves was during the nineties, when Democrats positioned such ideas as an alternative to Reagan’s right-wing supply-side agenda. Then, they became allied to spurious claims about a new economy and ended up providing ideological cover for Clinton’s embrace of fiscal austerity. This time, such ideas synced with the Biden’s administration’s interest in a more active industrial policy meant to counter the economic stagnation that had become evident during the previous decade and to tighten the strategic connections between key economic sectors and America’s geopolitical interests.

While the recentering of the national interest has allowed Keynesian ideas to enjoy greater influence, it has also reinforced the blind spot that has historically plagued that paradigm and that MMT had sought to correct. Even as fiscal and regulatory policy have become fully yoked to the needs of financial assets holders for minimum returns – a dependence that Daniela Gabor (2021) has referred to as the Wall Street consensus, dominated by an asset manager complex that demands comprehensive derisking for any and all projects it invests in, what fell by the wayside with the rise of Bidenomics is a critical focus on the economy’s financial infrastructure as an object of democratic decision-making.

Indeed, the Biden administration has been eager to disavow any interest in in challenging the autonomy of the Federal Reserve – one of its preferred ways to signal that there are “adults in the room” who take advice from experts. In this way, it has left the field open to the far right, which intuits much more readily that the advocates of independent central banking are false prophets, and it has made greater political control over monetary policy one of the key points of its blueprints for a more fascist future such as Project 2025. A progressive agenda that fails to engage that terrain, on which are situated the monetary drivers of the escalating concentration of asset wealth, will be unable find much sustained traction.

MMT has shown us where we need to look – where to direct our attention and bring the struggle. But its wish to beat mainstream economics at its own scientistic game, by advancing objectively better policies rooted in superior expertise, prevents it from recognizing what an effective political engagement might involve. The contributions to this forum resist the temptation to imagine alternatives as if any are readily available. Instead, they examine modern money as a complex tangle, composed of an endless range of dynamically evolving strategies and alliances that straddle any divide between public and private. The financial knot is tighter in some places than in others, but neither orthodox economics nor MMT gets the pattern into sufficiently sharp focus to see the openings and fissures.

In that sense, we should perhaps consider ourselves as occupying the mental space that Keynes did after he completed A Treatise on Money (Keynes 1930), which catalogued the extraordinary expansion of liquid financial instruments during the early twentieth century but had left him uncertain about the meaning of all this. When several years later he wrote the General Theory, his mind was on the day’s most pressing questions, above all the dramatic collapse in output and employment that had occurred during the previous years. While he recognized that such volatility could only occur in a monetary economy, he nonetheless considered it justifiable to let finance drop “into the background” (Keynes 1936: vii). Lerner viewed that as an infelicitous move, sensing correctly that it kept open the door to the restoration of an economic orthodoxy eager to sacrifice human livelihoods at the abstract altar of financial property. The contributions presented here (presented first at a symposium on the Gordian knot of finance held at the University of Sydney, generously sponsored by the Hewlett Foundation), take a step back and linger with the more open-ended curiosity that drove Keynes’ earlier engagement with the institutional logic of financial claims. How has the knot of modern money been tied?

Stefan Eich’s contribution examines money’s constitutive duality, the fact that it is public and private at the same time. He draws attention to the structural similarity of perspectives that think of the financial system as either primarily public or primarily private, and, engaging with MMT as well as other strands of “chartalist” theory, he argues that money is best seen as a constitutional project. The fact that money is at its core both public and private means that political openings always exist, even if those are never opportunities to reconstruct the financial structure from scratch.

Amin Samman asks what it is about the financial system that makes it so resistant to rational public policy intervention. To this end, he draws attention to the role of fictions in the functioning of finance – when speculative projections fail, the response is not sober reflection but a feverish acceleration of their production, eventuating in the installation of the lie as the modus operandi of capital. More earnest, truth-observant policymakers occupy a structurally impossible position, on the one hand interfacing with the delirious virtuality of capitalist finance and on the other attempting to be responsive to rational criticisms.

Dick Bryan argues that a preoccupation with how to undo or cut the Gordian knot may be misplaced. For each bit of loosening we achieve, capital has tricks up its sleeve to tighten its grip. Instead of focusing too much on the knot itself, we might think of ways to slip past it by designing financial connections that may not instantly become entangled in existing networks and their power concentrations. Challenging any clear-cut distinction between money and asset, he argues that crypto currencies could be designed to play that role.

Janet Roitman takes a different look at the image of the Gordian knot as a global imperial structure, and she asks whether it in fact attributes too much efficacy to the power of finance. While acknowledging the strength of the international currency hierarchy, she shows that dynamics challenging the dollar system arise from within the dynamic of capitalism itself. New financial technologies are instruments of economic competition, and in that capacity, they offer new opportunities for exploitation but inevitably also for the loosening of constraints, however limited or compromised such emancipation may be.

While Roitman turns our attention to the fissures in the global financial knot, Michelle Chihara concludes the forum by pointing out a major kink in the heartland of modern money. She argues that, for all our fascination with the ghost towns that the bursting of the Chinese real estate bubble produced, vacant property is a key aspect of the functioning of contemporary global capitalism. The jarring combination of vacant apartments serving as subsidized storage for transnational wealth on the one hand and a rapidly growing population of homeless and underhoused on the other, is giving rise to new forms of protest, reminding us that the grip of money is rooted in the compliances of everyday life.

Taken together, the contributions collected here shed light on different aspects of the tangle of promises, claims and commitments that constitute modern money. Such a perspective militates against the promise of a neatly executed, wholesale policy shift to reorient the economic system, but that does not entail a hard Hayekian anti-constructivism as the only alternative. MMT might be likened to a subject of psychoanalysis that, upon realizing that the world holds no deep secret, declares itself cured – but, when venturing back out, finds that its relationship to that world has undergone little practical change. It still has to do the work of deconstructing, transforming, or otherwise navigating the actual web of fictions, promises, lies, and obfuscations that it has built. In few areas of life is such thoughtful deconstruction more imperative than in our relationship to modern money, which is structured by so many layers of miseducation and misapprehension that transforming its practical operation is necessarily as much about revising our understanding as it is about getting our hands on the institutional machinery of its creation.

Martijn Konings is Professor of Political Economy and Social Theory at the University of Sydney. He is the author of The Emotional Logic of Capitalism (Stanford University Press, 2015), Neoliberalism (with Damien Cahill, Polity, 2017) Capital and Time (Stanford University Press, 2018), The Asset Economy (with Lisa Adkins and Melinda Cooper, Polity, 2020), and The Bailout State: Why Governments Rescue Banks, Not People (Polity, 2025).

References

Adkins, Lisa, Melinda Cooper and Martijn Konings. 2020. The Asset Economy, Polity.

Brown, Wendy. 2015. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution, Zone.

Coppola, Frances. 2019. The Case For People’s Quantitative Easing, Polity.

Dean, Jodi. 2020. “Neofeudalism: The End of Capitalism?”, Los Angeles Review of Books, May 12.

Feinig Jakob. 2022. Moral Economies of Money: Politics and the Monetary Constitution of Society, Stanford University Press.

Gabor, Daniela. 2021. “The Wall Street Consensus”, Development and Change, 52(3).

Gourgouris, Stathis. 2018. The Perils of the One, Columbia University Press.

Kelton, Stephanie. 2020 The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy, PublicAffairs, 2020.

Konings, Martijn. 2025. The Bailout State: Why Governments Rescue Banks, Not People, Polity.

Lerner, Abba P. 1943. “Functional Finance and the Federal Debt”, Social Research, 10(1).

Lerner, Abba P. 1947. “Money as a Creature of the State”, American Economic Review, 37(2).

Keynes, John Maynard. 1930. A Treatise on Money, Cambridge University Press.

Keynes, John Maynard. 1936. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Major, Aaron. 2014. Architects of Austerity: International Finance and the Politics of Growth, Stanford University Press.

Monbiot, George and Peter Hutchison. 2024. Invisible Doctrine: The Secret History of Neoliberalism, Crown.

Pelley, Scott. 2018. “Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell on the coronavirus-ravaged economy”, CBS News, May 18.

Petrou, Karen. 2021. Engine of Inequality: The Fed and the Future of Wealth in America, Wiley.

Slobodian, Quinn. 2018. Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism, Harvard University Press.

Smialek, Jeanna. 2022. “Is This What Winning Looks Like?”, New York Times, February 7.

Tooze, Adam. 2018. Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World, Viking.

Varoufakis, Yanis. 2024. Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism, Melville House, 2024.

Weber, Isabella M. and Evan Wasner. 2023. “Sellers’ Inflation, Profits and Conflict: Why Can Large Firms Hike Prices in an Emergency?”, Review of Keynesian Economics, 11(2), 2023.

Wray, L. Randall. 2015. Modern Money Theory: A Primer on Macroeconomics for Sovereign Monetary Systems, Palgrave Macmillan.