Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists Forgers?

Winnie Wong, with apologies to Linda Nochlin

…truth, whose mother is history, rival of time, depository of deeds, witness of the past, exemplar and adviser to the present, and the future’s counselor.

—Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote[1]

Linda Nochlin’s “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” first appeared in ARTnews in January 1971. It was described by ARTnews then as “based on a section of the anthology, Woman in Sexist Society: Studies in Power and Powerlessness,” which was to be published some months later, with the not-yet past-tense title, “Why Are There No Great Women Artists?” (cf. Woman in Sexist Society: Studies in Power and Powerlessness, edited by Vivian Gornick and Barbara K. Moran, NY: Basic Books, 1971, 344-366). Subsequently, that original––but therefore not first––version was “reprinted,” though “in revised form,” in Art and Sexual Politics: Women’s Liberation, Women Artists, and Art History (edited by Thomas Hess and Elizabeth Baker, NY: Macmillan, 1973, 1-43), where it was further described as “a shortened version.” Meanwhile, the first-but-not-original 1971 ARTnews version appears again, with other modifications, in Linda Nochlin’s Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays (NY: Harper & Row, 1988), and the same non-original was “pre-posted” on May 30, 2015 on the ARTnews website, in the “Retrospective” section of the June 2015 issue. However that pre-posted non-original essay does not appear to have been actually printed in the June 2015 issue of ARTnews, at least not in the copy currently residing in the Art History Library of the University of California, Berkeley. Separately, pdfs made from scanning the reprinted, revised, and shortened second copy (the one published in Art and Sexual Politics) appear online from time to time in various art educators’s course readings. Preferring the brevity and relative-originality of this second copy, as well as its fugitive accessibility on the internet, this is the version that I have rewritten here.

*

“Why have there been no great women forgers?” The question is curious, not merely to women, and not only for social or ethical reasons, but for purely intellectual ones as well. If the white Western male viewpoint, unconsciously accepted as the viewpoint of the art world professional, has proven to be inadequate, then it ought to follow that women have also been secretly, deceptively, and even subversively, painting works great enough to be recognized as masterpieces, but for which they cannot, or have not yet, claimed authorship. At a moment when a series of scandals has once again forced the art world to become more self-conscious—more aware of the nature of its presuppositions as exhibited in its own sureties and valuations, we ought to be confronted by many a great woman forger, skilled yet frustrated artists who have cunningly laid waste to the false ideology of authenticity spun by art experts, dealers, auctioneers, and museum directors. An art historical record corrected of the unstated domination of white male subjectivity ought to hold as many women forgers as it does Michelangelo, Marcantonio Raimondi, Pierre Mignard (or even Menard), Han van Meegeren, Elmyr de Hory, Lother Malskat, Zhang Daqian, Eric Hebborn, Tom Keating, and Wolfgang Beltracchi.

Today, the first reaction is still to swallow the bait and attempt to answer the question as it is put: to dig up examples of insufficiently appreciated women forgers throughout history; to rehabilitate modestly detectable, if interesting and productive, careers of forgotten copyists, insolent assistants, wayward ghost-painters, and defiant amanuenses; to “rediscover” the women behind male pseudonyms and masculine personae and make a case for them. We have indeed uncovered the careers of many wives, girlfriends, and daughters whose men appropriated their authorship in various guises. A court determined, and a movie popularized, that behind Walter Keane’s big-eyed waifs was the talent and imagination of his wife Margaret Keane. A 12th-century connoisseur fretted that the artist-emperor Sung Huizong’s personal and masculine calligraphy could not actually be distinguished from those of his palace ladies. An art historian is devoted to the theory that Vermeer’s daughter painted some of the greatest masterpieces attributed to him. A newspaper got the Australian Aboriginal artist Turkey Tolson Tjupurrula to sign a statutory declaration attesting that he autographed works that his daughters and daughters-in-law had painted for his dealer.[2] It is my own suspicion that Duchamp’s girlfriend Yvonne Chastel was “A. Klang,” the “sign painter” supposedly hired to paint the pointed forefinger of Tu m’, Duchamp’s last painting.[3] Such attempts at scholarly reevaluation are certainly well worth the effort, adding to our knowledge of women’s labor behind painting generally.

There are also of course the women who were accomplices or even orchestrators behind fabulous forgery schemes: Glafira Rosales was the art dealer who profited US$33.2 million by consigning to Knoedler Gallery 60 forgeries painted by Chinese (male) painter Pei Qian-shen. Helene Beltracchi served a prison sentence for fraudulently selling her husband Wolfgang’s forgeries, supposedly from her grandfather’s collection.[4] Olive Greenhalgh pled guilty to conspiracy charges for helping to pass off the “antiques” made by her teenaged son Shaun Greenhalgh, the multimedia forger prodigy. While crucial to the scheme, none of these women were art forgers themselves.

Then there are the women copyists who do not claim to be forgers, let alone great ones. Jane Stuart’s father Gilbert Stuart called her “boy,” and his “best copyist,” though as far as we know did not pass off any as his.[5] Marino Massimo de Caro, the orchestrator of the forgeries of Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius, stated that a woman in Buenos Aires duplicated the etchings for some of his fake books, but did not bother to name her.[6] In West Hollywood, a conservator and film set decorator Maria Apelo Cruz was tricked into copying a Picasso pastel drawing for the dealer Tatiana Khan, who pled guilty to various fraud charges in 2006.[7] The American collector Andrew Hall sued Lorrettan Gascard and her son Nikolas for selling him paintings purported to be by Leon Golub. Hall’s suit insinuated that Lorrettan Gascard (a former student of Leon Golub’s) may have forged the paintings herself, yet Lorrettan has not publicly claimed credit for those paintings.[8] We could imagine rewriting a career for these women as forgers reluctant to unmask themselves. A great deal could still be done in this area, but unfortunately, such attempts do not really confront the question “Why have there been no great women forgers?”; on the contrary, by attempting to answer it, they merely reinforce its negative (or positive) implications.

There is another approach to the question. Many contemporary feminists might assert that there is actually a different kind of greatness for women’s forgery than for men’s. They might posit, that, due to the unique character of women’s situation and experience—their meticulous care for detail, their love of craft, their uncanny ability for dissimulation—that their forgeries are so skilled that they have thus far been impossible to detect.

This might seem reasonable enough: in general, women’s experience and situation in society, and hence as forgers, is different from men’s, and certainly a body of forgery of all kinds produced by women secretly but entirely disunited in character and intent might indeed all be so masterful as to be unidentifiable presently. Perhaps possessing higher intelligence and survival skills in general, women criminals may simply be less likely to be caught. Unfortunately, though this remains within the realm of possibility, as far as we can know, so far, it has not occurred.

It might also be asserted that women are simply more inward-looking, and therefore not as likely to engage in the imitation or appropriation of another’s stock or style. Perhaps self-expression is an innately more feminine drive, and route imitation and self-effacement unlikely garner their interest. But is Richard Prince really less slavish than Sherry Levine? Is Jeff Koons less subtle than Sturtevant? Is Banksy more anonymous than the Guerrilla Girls? Is Tino Seghal less evasive than Lutz Bacher? In every instance, women appropriationists would seem to be closer to other artists of their own period and outlook than they are to each other.

The problem lies not so much with the feminist conception of what femininity in forgery might or might not be, but rather with a misconception of what forgery is: with the popular idea that forgery is the direct, personal expression of individual emotional experience—a translation of frustrated ambition into artistic deception. Yet forgery is almost never that; great forgery certainly never. The making of a forgery involves a self-inconsistent language of form, more or less dependent upon, while also free from, given temporally-defined conventions, schemata, or systems of notation, which have to be learned or worked out, through study, apprenticeship, or a long period of individual experimentation. In order to defraud an art market and institutional establishment, the great forger must endure, for some period, disciplined anonymity. Yet in order to embrace the notoriety of a great forger, one must also ultimately accept criminal liability and then fascinate the public with performances of heroic iconoclasm.

The fact is that there have been no great women forgers, so far as we know. There are not even many interesting and good ones who have not been sufficiently investigated or appreciated. That this should be the case is regrettable (or laudable), but no amount of manipulating the historical or critical evidence will alter the situation. There are no women equivalents for van Meegeren or de Hory, or even in the invented mode, Ern Malley. If there actually were large numbers of “hidden” great women forgers, or if there really should be different standards for women’s forgery than men’s—and, logically, one can’t have it both ways—then what are feminists fighting for? If women have in fact achieved the same status as men in the criminal arts, then the status quo is fine.

In other artistic misconduct, indeed, women have achieved equality. While there have never been any great women forgers, there have been scandalous women literary forgers and impersonators. The biographer Lee Israel successfully forged fake personal letters of famous authors and signed their signatures, using her broken tv as a lightbox. After serving a short period of house arrest, she wrote a short memoir apologetically entitled, “Can You Ever Forgive Me?” A Hollywood biopic made from it probed the depths of her pathos, and has her sincerely and tearfully testifying to the court at her sentencing hearing, “I think I have realized that I am not a real writer…and that it was not worth it.” Helen Darville, as “Helen Demidenko,” published a novel which readers were led to believe was based upon her Ukrainian family’s collaboration with the Nazis in the Holocaust. The book won three major literary awards in Australia. At the ceremony where she accepted one, Demidenko performed Ukrainian dances dressed in a traditional Ukrainian blouse, the kind of performance she would increasingly embrace over two years. But the intense literary debate over the book’s anti-Semitism was thrown into deeper shock when her ethnic identity—utterly lacking any Ukrainian heritage––was unmasked by her parents and high school teachers in the news media. After that, numerous instances of plagiarism were newly discovered in the novel, and Demidenko/Darville was scrutinized, in book-length academic studies, for authentic signs of remorse over the banality of her evil. By finding instances of plagiarism throughout the previously-award-winning book, it would seem that the literary world was condemning her fraud as also a forgery, multiplying, rather than vindicating, her moral crimes. It could not be that women as a whole shy away from the turpitudes of lies, fraud, plagiarism, impersonation, immorality, bigotry and other improprieties in the arts.

It is no accident that the whole crucial question of the conditions generally productive of great forgery has so rarely been investigated. Yet a dispassionate, impersonal, sociologically- and institutionally-oriented approach would reveal the entire romantic, elitist, individual-glorifying and monograph-producing substructure upon which the profession of forgery detection, unmasking, heroization and popularization is based.

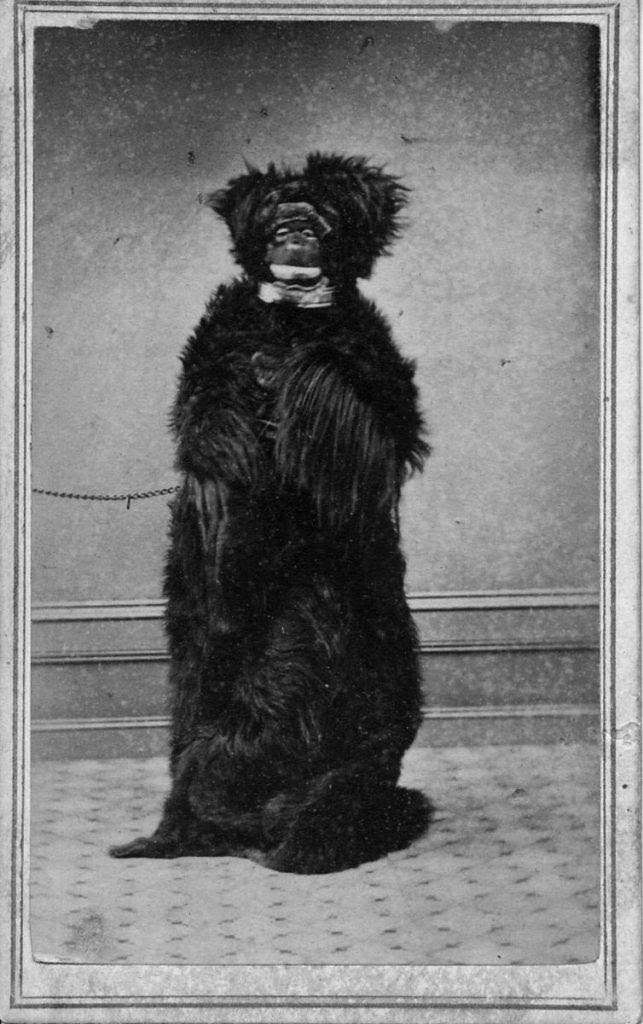

Underlying the question about women as forgers, we find the whole myth of the Great Forger—subject of a handful of movies and biographies, masterful, impish, misunderstood, bearing within his person since birth a mysterious essence, called Thwarted Genius.

The magical aura surrounding the representational arts and their forgers have, of course, given birth to forgers’s autobiographies and self-representations since the earliest times. Interestingly enough, the same magical abilities attributed by Vasari to Michelangelo and his forgery of an “ancient” Cupid[9]—the ability to copy anything, “the genius to do this and more,” the lack of any corrupt motivation except the hoodwinking of ignorant collectors—is repeated as late as the recent 2014 documentary on Wolfgang Beltracchi. The fairy tale of the Boy Joker, able to copy any artist’s style, quickly and easily, but finding his own art rejected by dealers and experts who therefore deserve to be outwitted, has been stock-in-trade of forger mythology since Vasari immortalized Michelangelo and embarrassed the Cardinal San Giorgio. Through mysterious coincidence, later forgers were all portrayed as tricksters who exposed the art market in similar manner. Even when the Great Forger was quite avaricious in his long-running crimes, his motivations in retrospect always seem to contain subversive artistic intent. In the end, the art establishment is portrayed as so inexpert that the forger’s greatest fear is that no one will believe he is the true maker of the fakes. Pierre Mignard painted a “Guido Reni” to test and humiliate his court rival Le Brun. Han van Meegeren demonstrated his abilities in court in order to prove that he could really paint “Vermeers,” and that he had not sold Dutch national cultural property to the Nazis. Tom Keating planted “time bombs” in his forgeries that conservators would overlook but that would later prove his hand unequivocally. Lothar Malskat ended up suing himself and serving as both expert and witness at his trial. In the theory of forgery sleuths, and often the great forgers themselves, a great forger always eventually unmasks himself, because revealing his craftsmanship is the only way to bring down the art establishment that rejected him as a great artist long ago. He then writes a memoir, a tell-all or a how-to handbook, before starring in a TV series, a movie, a documentary or two. The public cheers, admires, and respects him for the ruse, for it is only snobby experts and ignorant collectors who have committed the true crimes against art.

Despite the actual basis in fact of some of these late-bloomer stories, the tenor of such tales is itself misleading. Yet all too often, art historians, while pooh-poohing this sort of narrative based around artistic intention, nevertheless retain it as the unconscious basis of their scholarly assumptions. Forgery biographies, moreover, forward the notion of the Great Forger’s mastery of his craft, as demonstrated by the social and institutional structures which rejected his art but that now he has duped. This is now the golden-nugget theory of Thwarted Genius. On this basis, women’s lack of achievement in forgery may be formulated in a disturbing syllogism: If women have been thwarted by the social and institutional constructions of art, they would reveal its bias through forgery. But they have never revealed it. Q.E.D. women do not have the golden nugget of artistic genius, which has not even been thwarted.

Yet if one casts a dispassionate eye on the actual social and institutional situation in which important forgers have been valorized throughout history, one finds that the fruitful or relevant questions for the historian to ask shape up rather differently. One would like to ask, for instance, from what artistic traditions were forgers were most likely to come at different periods of art history? What proportion of major forgers work within traditions in which originality and auto-genesis are overburdened with aesthetic value? Despite the Orientalist sentiment that constructs Chinese or “Eastern” cultures as ones that prize honorific emulation or accept outright piracy, one might well be forced to admit that a larger proportion of forgers, great and not-so-great, were white and Western European.

As to the relationship between forgery and culture, an interesting paradigm for the question “Why have there been no great women forgers?” is the question: “Why have there been no great women forgers from China?” If, in other words, Chinese civilization accords such high value to copying, why have there not been armies of great Chinese women forgers, to diametrically oppose the utter lack of Western women forgers? Even in contemporary Dafen village, a community of 6000 registered painters derided as forgers and assembly-line copyists, the vast majority of the painters are men rather than women. Could it be possible that thwarted genius is missing from the Chinese make-up in the same way that it is from the feminine psyche? Or is it rather that the kinds of demands and expectations placed before both non-Westerners and women—radical self-invention, outrageous rebellion, brazen public performance—simply makes the heroization of racialized, ethnicized, or gendered lawbreakers unthinkable?

When the right questions are finally asked about the conditions for producing forgery of which the production of great forgery is a subtopic, it will no doubt have to include some discussion of the situational concomitants of psychology and skill generally, not merely of artistic craftsmanship. As Foucault and others have stressed, the modern authorial persona is built up minutely, step by step, from infancy onward, and the patterns of discipline-punishment may be established so early that they may indeed appear to be innate to the ahistorical observer. Such investigations imply that scholars will have to abandon the notion, consciously articulated or not, of artistic authorship as innate, even for those who have been denied it.

The Question of the Original

We can now approach our question from a more reasonable standpoint. Let us examine such a simple but critical issue as the availability of original masterpieces to aspiring women forgers, from the period after the establishment of public museums to the present day. During this period, careful and prolonged study—indeed, love––of original masterworks has been imagined as essential to the production of any forgery with pretentions to pass muster, and to the very essence of a Perfect Copy, which is generally accepted as the highest category of forgery. Forgers are thought to admire and eventually develop an obsession for the artists whom they are emulating, in various ways even modeling their own lives after them. In movies, forgery schemes are often motivated by an art thief who plans to steal a work out of some misguided sense of personal ownership, while the original is meticulously imitated by the forger to hide the theft. The Perfect Copy is supposed to be what the great forger produces—a copy so exactingly duplicative of the original that no one can tell the difference.

The hypothetical of indistinguishability has occupied many an aesthetic philosopher over the twentieth century. But in fact forgers rarely need much access to the original to make a passable forgery, for great forgers are never copyists. A brief survey of the history of forgery reveals: masterpiece forgeries are almost always inventions—original works that do not reproduce any existing work. Han van Meegeren’s infamous “Vermeers” were not intimate domestic bourgeois genre pictures but large, Caravaggio-influenced religious canvases that fooled art historians and museum directors into identifying them as the “missing link” between Vermeer’s early and late periods. Riverbank, a painting that divides historians of Chinese art into two irreconcilable camps, is either a recovered and restored 10th-century painting by Dong Yuan or a 20th-century pastiche by Zhang Daqian. As the forger Wolfgang Beltracchi put it, what a successful forger needs to do is to find is a painting that doesn’t appear in any catalogue of works, but that is mentioned or hypothesized in the art historical literature. In other words, a successful forgery is an original invention that fills in the narrative history in which the artist’s works have been organized in retrospect. As in the case of van Meegeren’s forgeries, the forger’s audacity is all the more canny when he dupes the most prominent art historian of his day, whose theory or narrative is “proven” by the newly “discovered” masterwork.

An exception among the great forgers who successfully passed off copies is the American Mark A. Landis, famous for donating all of his forgeries to small museums throughout the United States, for no apparent financial gain. Landis’s forgeries are modestly sized reproductions of major artists’ minor works. His method is so rudimentary that he simply pastes photocopies made from art catalogues directly onto wood panels that he has cut for him at Lowe’s hardware store. He stains the wood panels with instant coffee, and then paints over the photocopies, simulating the look of thick paint with “that stuff I got” from the craft supply chainstore Hobby Lobby. Said Mark Landis while reproducing a portrait: “Heaven only knows how he painted it. They’re not going to know either, so…..” Landis’ forgeries are easily confirmed through the most cursory of visual “tests,” for example, examination with a magnifying glass would reveal the dot matrix print patterns in the photocopy beneath the paint, as would a simple visual inspection with a black light. But technically-aided visual scrutiny is not even necessary, for the registrar who first detected Landis’ forgeries figured out the scam by simply finding other copies of the same works donated to other museums by the same man—some of those gifts were even announced with photographs in press releases. What is remarkable of Landis’ forgeries is not that they are perfect fakes—in fact they are ridiculously imperfect copies. Posing as an eccentric art collector and potential benefactor, what he elegantly demonstrates is how unlikely museums would subject gifts from a benefactor to any level of scrutiny at all. As one museum director put it, “He knew where to hit us. Our soft spot. Art and Money.”[10]

I have gone into the question of the unimportance of originals, a single aspect of the automatic, popularly maintained mythos of forgery, in such detail to demonstrate that the universality of this discrimination against women lies not in this particular facet of institutional access. In fact, the focus on the forger’s craft belies the importance of the performative role of those––often women––who pass off the forged works. This fixation sustains the ongoing fetishization of the original masterpieces and the institutions that protect and trade on them, and only rehearses the fantasy of the gendered relationship between great male artists and their preferred artistic object—the female nude. The power of this gendered relation lies in the uncritical notion that the male artists’ relationship to the nude should be the same relationship as the forger’s relationship to the original masterpiece—a relationship of possession, dominance, and (moral) violation. In perfect opposition, women are inevitably cast in the opposing role as guardians of institutional authority and caretakers of institutional property. This is most evident in popular art heist movies, where women take on the nerdy and rule-following roles of curators, archivists, insurance experts, or conservators, distracted from their professional duty by handsome but roguish male thieves. Deprived of the motivations for (counter-) revolution or even intentional disruption, it is almost unheard for women to seek redress in forgery for a higher artistic cause.

It also becomes apparent why women who were able to compete on far more equal terms with men in literary forgery or plagiarism are vilified and deemed impersonators. When women are found to have committed misconduct in the arts, condemnation rather than heroine-ization often ensues — their fakery is never seen to serve a nobler or even picaresque causes, but seriously disturbing ones. They are understood to be misguided figures, unable to take possession of their true selves and make sense of the world with it. Naturally this oversimplifies, but it still gives a clue as to the discomforting focus on Lee Israel’s inexplicable deficiencies in personal hygiene (her inability to smell her cat’s feces under her bed), or the grave moral excoriation lodged against Helen Darville/Demidenko’s dystopian family fantasy.

Of course, we have not even gone into the “fringe” requirements for major forgers, which have been, for the most part, both normatively and socially closed to the figure of “woman.” In the modern period and after, the Great Forger, after he is unmasked, takes on a cheeky public role as his authorship can now be revealed. He now revels in counterintuitive declarations and even contradictory claims, he establishes new relationships with biographers, historians, documentary filmmakers, travels widely and freely, and perhaps becomes involved in other postmodernist hoaxes and intrigues. Nor have we mentioned the sheer organizational acumen and ability involved in rehabilitating oneself as a celebrity. An enormous amount of self-confidence and courage is needed by a great mastermind-turned-thespian, both in the running of the production and selling of forgeries, and in the control and maintenance of numerous rehabilitative postures. In all of these performances, the great forger’s true self––his Thwarted Genius––is never in doubt.

The Lady’s Employments

Against the single-mindedness and commitment demanded of a great forger, we might set the image of the “lady forger” established in a popular novel that imagines one. The insistence upon a wrenching internal moral debate over the value of the original—the looking upon great art as a masculine presence, even, as the object of sexual desire—militates against any real malfeasance on the part of women. It is this emphasis which transforms serious defiance into emotional self-sabotage, busy work or occupational therapy, and even today, in urban bastions of female competence, tends to distort the whole notion of what authenticity is and what kind of social role it plays.

In the American novelist B.A. Shapiro’s not very widely read The Art Forger, published in 2012––a book offering one of the few fictional treatments of a woman art forger in popular literature, readers are warned against the snare of forgery at which she is fully capable to excel. The novel’s protagonist, Claire Roth, is a commercial reproduction artist (working for “Reproductions.com” as a “certified Degas copyist”). She is commissioned by her former lover’s art dealer to reproduce a painting in exchange for cash and the opportunity for an exhibition of her own work. The painting she is to copy is gradually revealed to her. When she realizes that it is Edgar Degas’ After the Bath, a (fictional) painting stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1990, Claire responds to it with breathless, physical subjugation:

My heart races. I’m going to have the incredible good fortune of living with a work by Degas, touching it, breathing it in, studying its every last detail, ferreting out the master’s secrets. It’s a great gift. Perhaps the greatest. One that will inform my painting forever. Sweet. Incredibly sweet. Now I really can’t breathe. …I stand speechless, mesmerized, unable to move to help him, unable even to think. Degas, Degas, Degas is the only refrain my brain can dole out.[11]

This bit of paralyzed worship of man’s genius has a familiar ring. Propped up by a bit of Lacanism, it is the reversal of the very mainstay of artistic masterworks in the popular imagination. Of course, the popular equivalence of the 19th-century male artist’s painting of his female lover’s nude body will rear back its misogynistic head. For Claire, the Degas painting takes on the immobilizing presence of an aggressive male body: “The room is dark, and I’m lying on my mattress. I’ve been up most of the night. I feel After the Bath like a human presence: massive, breathing, haunting, yet also comforting. As if Degas himself is with me, risen from the dead. His genius, his brushstrokes, his heart.”[12] This ideological phantasy is then transferred to the charming male art dealer who owns the painting, whom Claire naturally desires. (Luckily he falls in love with her too.)

As the plot twists its melodramatic ways, Claire comes to discover that the Degas painting is itself a forgery, but she nevertheless copies it—so hers is therefore not a forgery but “a copy of a copy.” She produces a perfect fake, and all are fooled. Meanwhile, the narrative takes us back to a period three years earlier, in which Claire attempted to claim credit for ghost-painting a work of her then-boyfriend-and-former-art-teacher (“I loved him and wanted to help him.”), a painting which was then (fictionally) in the MoMA collection. A museum committee rejected her claims, but the ordeal ended with her ex-boyfriend-teacher committing suicide, a tragedy for which she continues to blame herself. Back in the present day, her new lover-the-art-dealer is thrown in jail for selling the forgery and suspicion of being connected to the Gardner heist. Visiting him in jail, Claire reveals to him that she believes the “original” to be a forgery itself. Unfortunately, the only way to prove his “innocence” in the forgery scam would be to find the original-original Degas. She finally does so, in the home of Isabella Stewart Gardner’s (fictional) niece’s granddaughter. Differently from the forged-Degas painting, the original-original Degas depicts Isabella Stewart Gardner in the nude, which apparently suggests a tantalizing love affair between Isabella and Degas. As if this closed circle of elective affinities between painted/loved object and artist-author-lover-owner were insufficient, Claire finally discovers that the original/actual forger of the Degas painting was also the lover of Isabella’s niece.

In sum, the fictional woman forger in B.A. Shapiro’s novel ends up occupying virtually every subject position a woman is expected to hold in the history of art: ghost-painter to her lover/former teacher, skilled reproduction painter, diligent provenance researcher, beloved of her dealer, savior of an art thief, and struggling contemporary artist. But ultimately, and most critically, she is anything but the actual, titular, art forger. That person turns out, however outlandishly, to be a man. Claire herself never produces a forgery—only a perfect fake that happens to be a copy of a copy. This exonerates her totally and makes it possible for the moralistic happy ending: she is recognized as an artist “in her own right” (that is, not exactly a great one). As in 19th-century etiquette manuals, Claire has excelled in many occupations without acclaim, and success for her is defined as a commercial gallery show put up by her lover from prison.

Lest we feel we have made a great deal of progress in this area in the past 50 years, it would seem that even in our cultural imagination, a woman with the skills to produce a perfect fake would do so only in service of her boyfriends, lovers, teachers, and dealers, and even then only because she has found a morally-acceptable loophole. Now, as in the late-twentieth century, women’s professionalism feeds the reliance of the daring, risk-taking man who is engaged in “fake” work and can (with a certain justice) point to his girlfriend’s reliable toolkit of excellent skills. For our culture, the “real” work of women is only that which directly or indirectly serves her desire for romantic love. Any other commitment falls under the rubric of delusion, selfishness, egomania, or at the unspoken extreme, castration anxiety. The circle is a vicious one, in which self-satisfaction and meniality mutually reinforce each other, in life as in fiction.

Accomplices

But what of the small band of villainous women who, despite obstacles, have achieved infamy in forgery scams? Are there any qualities that may be said to have characterized them, as a group and as individuals? While we cannot investigate the subject in detail, we can point to one striking fact: almost all women accomplices in forgery scandals were either the wives, daughters, or mothers of male forgers, or, they worked in concert with another male accomplice who was their husband. In contrast, the reverse would be quite unusual for women copyists: the few we know of rarely receive artistic or criminal assistance from their lovers, husbands, brothers, or sons. It appears to be quite difficult for women to appropriate the labor of their male family members, but the opposite is true almost without exception for their masculine counterparts. In the rehabilitation of great forgers, wives and daughters too play a crucial but supportive role: Helene Beltracchi’s central role in performing the “provenance” story of Wolfgang Beltracchi’s forgeries have already been mentioned. After their release from prison, she and Wolfgang published a joint autobiography and their prison love letters—publications which generated further public endearment. Zhang Daqian’s daughter, Chang Sing Sheng, studied at Berkeley with the art historian James Cahill, who was adamant and tireless in tracking Zhang’s forgery career, and arguing for the attribution of major canonical works to Zhang’s mischievous ways.

It would be interesting to investigate the role of wives, girlfriends, daughters and mothers in forgery enterprises more generally. We may well extend this inquiry to the role of queer partners in the successes of great forgers as well—Elmyr de Hory’s personal assistant and companion, Mark Forgy, wrote a biography honoring de Hory’s career, in which he declares “even I was a victim of his lies,” but that “nothing assails my love for him.”[13]

In the absence of any thoroughgoing investigation, one can only gather impressionistic data about the presence or absence of affective labor by supportive women and men in the lives of great forgers, and whether women may indeed be granted less of this criminal assistance from their romantic and domestic partners. One thing, however, is clear: for a man to opt for a career in forgery has required a certain degree of collaboration, or at least quiet acquiescence, from the family and friends around him.[14] And it is probably by appropriating, however covertly, women’s labor, that great forgers have succeeded, and continue to succeed, in the world of forgery.

Elizabeth Durack

It is instructive to examine one of the few successful and accomplished women artists accused of “forgery,” Elizabeth Durack (1915-2000), whose work as Aboriginal male artist “Eddie Burrup,” because of the repulsion wrought upon by that revelation, stands as a challenging episode to anyone interested in faking and the history of the self generally. Partly because of the public outrage that the scandal provoked, Elizabeth Durack is a woman forger in whom all the various conflicts, all the internal and external contradictions and struggles typical of her sex and profession, stand out in severe relief.

The success of Elizabeth Durack’s paintings as “Eddie Burrup,” an invented persona for whom she (and her daughter, also her gallerist), created an entire website, emphasizes the role of gender and racial identity in relation to achievement in global contemporary art. We might say that Durack, at the late age of 79 after a long career as a West Australian painter who primarily depicted Aboriginal land and people, picked a deplorable time to adopt the “nom de plume” or “alter-ego” of an (invented) Aboriginal male artist. She had long come into her own in the mid-twentieth century, being only one of three women chosen for the 1961 exhibition Recent Australian Paintings at the Whitechapel Gallery in London.[15] When, in the late 1990s she began painting and exhibiting a new style of “morphological paintings” and her daughter told her that they only “made sense” as Aboriginal work, Australian Aboriginal Art had just taken the art world by storm. A major change in social and institutional support for contemporary art by Aboriginal peoples was under way: with the rise of global contemporary art, the acrylic on canvas and bark paintings from the Papunya Tula communities, whose subject matter were “Dreamings” passed down through paternal or maternal authority and collectively painted by tribal family members, were much in demand in the contemporary art galleries in New York and intertwined with a broader political demand for by Aboriginal peoples for land restitution and cultural rights in Australia.[16] In late-twentieth-century Australia, there was a dramatic reinvention of Australian contemporary art through its seemingly abstract, colorfield, Aboriginal painting. Aboriginal art was then a newly and highly fertile aesthetic field, and Elizabeth Durack—a white woman—became one of its most odious “practitioners.”

She followed in two other scandals in which two white men acknowledged or claimed to be makers behind Aboriginal artist’s works: John O’Loughlin, an art dealer, sold works “by” an Aboriginal artist he represented, Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, whom he claimed as an honorary cousin; and Ray Beamish, the Welsh-born white ex-husband of Aboriginal woman artist Kwementyaye (Kathleen) Petyarre, claimed authorship for several of her works, including a prize-winning canvas. The existence of white men behind Aboriginal artists’ works raised the specter of inauthenticity (or more specifically anti-auto-genesis or false-self-labor) that redounded as “forgery” upon Possum and Petyarre.[17] It was as though the public demanded that Australian Aboriginal artists present themselves as singular, individual geniuses in the Western tradition, though they would not be allowed to appropriate the labor of white bodies under their authorial names. In contrast, accusations of forgery against Elizabeth Durack inverted that commandment: by disallowing a white woman artist the male fantasy of artistic self-invention because she had crossed the embodied boundaries of race and gender.

Daughter of a settler-colonial father, who left she and her sister on their own as teenagers to manage their settler property of Ivanhoe Station in Western Australia, Elizabeth Durack claimed “interfamilial” affinities with the Aboriginal peoples who labored for them.[18] She was often interviewed by the art press alongside Jeffery Chunuma Rainyerri, an Aboriginal man and elder of the Miriuwung Gajerrong community,[19] who called her his “mum,” and he her “classificatory son.”[20] Although her attitude was criticized as paternalistic (though not maternalistic), evidently he and other Aboriginal men in her life were influential in directing her toward her life’s work. Although in her late years Elizabeth Durack would acknowledge the anger and disapproval of her critics—who called her, part of the “squattocracy,” and her deception as Burrup a “fucking obscenity,” and “the ultimate act of colonization”[21]—it is obvious that her entitled self-narrative as a white female benefactor of the Aboriginal communities was developed since childhood and formed the grounds for her later course of behavior.[22]

“I don’t think it would have worked through Elizabeth Durack,” she told an interviewer, who asked why she didn’t just claim the paintings under her own name. “I would have been lost…. It was Eddie Burrup that somehow brought it to life. I can’t … I can’t … I can’t answer it. I simply can’t answer it.” When asked whether she had only fraudulently created an Aboriginal persona in order to succeed better on the art market, she insisted that the Burrup paintings had been hung in her daughter’s gallery but were not for sale, and that her daughter only later begrudgingly sold them. After she unmasked herself to the art historian Robert Smith as the painter behind the Burrup paintings,[23] she claimed that her daughter also contacted the “very few” buyers who had bought them and only one buyer asked for a refund. Durack, in other words, did not follow in the defiant model of the great forgers[24]—whose self-narrative often begins with personal rejection of their own work by the art world (Durack had by that time been featured in over 66 solo exhibitions), and who purposefully sought to entrap gullible critics, experts and buyers. At the same time, we might speculate that the long history of male artists’ gender-bending alter-egos might have been an even stronger influence in her decision to reinvent her own destiny and to paint in the spiritual guise of a man.

In disarmingly confusing post-Lacanian fashion, Elizabeth Durack would insist that Eddie Burrup was not a character from her imagination, but rather a real, if mysterious, force: “I can’t. I can’t explain it. It’s quite worrying. But as I say, I’m not really losing it completely. But I am part…I suppose one is…everyone’s part of certain mysterious forces, you know, that keep you…keep you going. But what’s been the strange thing is that when you most readily run of energy, there’s always energy. I could paint every day if I had the time, or if the days weren’t broken, as Eddie Burrup. Sort of something that’s ongoing, that draws me out.”[25] Resisting standard postmodern language, she also avoided calling him a fictive character or an alter-ego, preferring such imprecise claims as: “Maybe he’s a figure of my persona.”[26]

While consistently rejecting conventional anti-heroic motivations for her actions, she insisted on disavowing an equivalence between herself and Eddie Burrup. Like Durack, Jeffrey Chunuma Rainyerri also spoke of Eddie Burrup in the third person, referring to him as “that old man behind her shoulder”:

You tell im ‘e’s got to come up here, sit down and talk to us…It’s no good what e’s doing. That old man behind her shoulder. She got to stop doing that.[27]

It is disturbing and tragic that this successful artist—unsparing of herself in her lifelong study of Western Australian landscape and figurative painting, diligently pursuing her indigenous subjects in rural isolated surroundings, industriously producing canvases throughout the course of a lengthy career; firm, assured, and incontrovertibly masculine in her style; recipient of honorary doctorates and national attention; should fail so spectacularly in life to come to terms with her white colonial privilege; it is more tragic still that she should fail, in her own self-unmasking, to evaluate her own place in the racist imperialism that undergirds Australian society more broadly. It has thus been argued that it was her subconscious, wracked with guilt from her heritage and worldly success, that spurred her to take on a neurotic-colonialist fantasy of Aboriginal identification.

The difficulties imposed by society’s implicit demands on the woman forger add to the impossibility of celebrating Durack’s enterprise. Although widely associated with forgery, no critic actually accused her of copying or plagiarizing any formal element, nor even style, of Burrup’s paintings from Aboriginal sources or designs. Neither does Eddie Burrup exist in history, nor was he known as a great artist whose place in the history of art she had misused. In short, Durack’s “forgeries” are not copies or even fakes at all—they are new and original contemporary works that a White public troublingly (in retrospect) accepted as the work of an Aboriginal man. Moreover, though we might insist that Eddie Burrup does not exist in our reality, Durack seemed to insist he was real in some mystical sense or at least took no responsibility nor credit for inventing him. The narrative she attempted to advance after unmasking herself furthermore did not follow at all in the usual formulae of forger rehabilitation. Durack did not brazenly lay claim to upturning a cynical art market, to testing a gullible art establishment, nor to provocatively challenging gender and racial binaries. Not only did she decline to adopt the popular performances which have been typical of great forgers in the modern and contemporary eras, she, like other women malfeasants in the arts, was far from valorized for their daring to subvert the institutional norms of the art world. Even in the case of this notorious artist—and whether we like “Eddie Burrup” or not, we still must acknowledge the subversiveness of Elizabeth Durack’s apostasy—the voice of the feminine mystique and its potpourri of ambivalent narcissism and internalized guilt subtly dilutes and subverts that total inner confidence, that absolute certitude and self-determination (amoral and anti-aesthetic), demanded by the most defiant and audacious work in forgery.

Conclusion

Hopefully, by stressing the process of normative, or public, rather than the individual or private, preconditions for heroine-ization in forgery, we have provided a paradigm for the investigation of other areas in this field. By examining in some detail the various instances when our culture inexplicably chose not to imagine or glorify women forgers, we have suggested that it may be culturally impossible for women malfeasants to achieve notoriety or admiration on the same footing as men, no matter what their rebelliousness, villainy, or pathos. The existence of a tiny band of infamous, if not great, women accomplices, impersonators, fakers, plagiarists, ghost-painters and appropriationists throughout history does nothing to gainsay this fact, any more than does the existence of a few badasses or token mischief-makers under various adjacent definitions of forgery.

What is important is that we face up to the reality of our history and of our present situation. Authorship has been, in our history, a white- and masculine-coded privilege. Despite what we might think, forgery does not undo that privilege. Forgery is rather a subversive takeover of that privilege, a theft of history and property that transgresses legal, artistic, moral and cultural norms. When unmasked, forgers remind us how comically unfair the art world is in its declarations of greatness, and how untenable is the false ideology that separates the good from the great. But in our culture, sympathy for those who rebelled as forgers so far extends only to men. This “himpathy” is part of the logic of misogyny that the philosopher Kate Manne decodes. It is why women can never be great, whether or not we have been bad.

Winnie Wong is a Professor of Rhetoric at the University of California, Berkeley. She is the author of Van Gogh on Demand: China and the Readymade, and the coeditor of Learning from Shenzhen. Her forthcoming book is The Many Names of Anonymity: Portraitists of the Canton Trade.

[1] Jorge Luis Borges, Collected Fictions, trans. Andrew Hurley, (London: Penguin Books), 1999, 94.

[2] Susan McCulloch-Uelin, “Painter tells of secret women’s artistic business: I signed my relatives’ work”, The Weekend Australian, April 17-18, 1999.

[3] The “A. Klang” (German for a “sound”) who “signs” underneath the wrist of the pointed forefinger in Tu m’, and traditionally said to be a professional sign painter whom Duchamp hired, has not been identified in the Duchamp literature. However, Yvonne Chastel was seen painting the colour scale of lozenges of Tu M’ in Marcel Duchamp’s studio on the evening of April 12, 1918. See Jennifer Gough-Cooper, Jacques Caumont and Pontus Hulten, eds., Marcel Duchamp: Work and Life: Ephemerides on and about Marcel Duchamp and Rrose Selavy 1887-1968, MIT Press, 1993, unpaged.

[4] His sister-in-law Jeanette Spurzem was also involved.

[5] “Jane, Heir of the Stuart Genius––A Rhode Island Master’s Exhibition,” Gilbert Stuart Museum Bell Gallery, Rhode Island, 2016.

[6] Nicholas Schmidle, “A Very Rare Book,” The New Yorker, Dec 16, 2013. Schmidle does not report whether he asked De Caro for her name.

[7] On the scheme related to Tatiana Khan, see 2010 WL 326207 (C.D.Cal.) (Trial Pleading), USA v. Tatiana Khan, No. 10-0030M, January 7, 2010. Maria Apelo Cruz is founder of MJ Atelier where she is described as a “creative force” and who has the ability “to create and paint in any style.”

[8] Mark Haywoard, “Lawyer: Art dealers on trial still believe Golub works are not fake,” New Hampshire Union Leader, November 26, 2018.

[9] Sándor Radnòti, The Fake: Forgery and its Place in Art, trans. Dunai, (Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield), 1999, 1. According to Radnòti, Vasari’s version borrows “extensively” from Condivi, “so as to repay him in kind for lifting material from the first edition of his own book.”

[10] The director of the Hillard Museum, quoted in Art and Craft, 2014.

[11] B.A. Shapiro, The Art Forger: A Novel, 43-44.

[12] Shapiro, The Art Forger: A Novel, 53.

[13] Mark Forgy, The Forger’s Apprentice (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform), 2012, 334.

[14] As the biography John Godley imagined van Meegeran thinking (about his wife Jo): “He must discover an intermediary who could be trusted—perhaps Theo? perhaps Jo?—but they would guess the truth…” John Godley, The Master Forger (New York: Wilfred Funk), 1951,138.

[15] Sarah McCulloch, “What’s the fuss?” The Australian Magazine July 5, 1997, 18.

[16] Fred Myers, “Representing Culture: The Production of Discourse(s) for Aboriginal Acrylic Paintings” Cultural Anthropology, 6:1 (Feb 1991), 26-62.

[17] Fred Myers, “Ontologies of the Image and Economies of Exchange,” American Ethnologist 31:1 (Feb 2004), 5-20.

[18] Marguerite Nolan, “Elizabeth Durack, Eddie Burrup and the Art of Identification,” in P. Knight and J. Long, eds., Fakes and Forgeries: The Politics of Authenticity in Art and Culture (Cambridge Scholars Publishing), 2004, 136.

[19] Chunuma was one of the lead witnesses for the Miriuwung Gajerrong land claim. The Full Federal Court recognised the native title rights of the Miriuwung Gajerrong people on December 9, 2003. Further history: MG Corporation

[20] National Film and Sound Archive of Australia: “Australian Biography: Elizabeth Durack,” 1997.

[21] Louise Morrison, “The Art of Eddie Burrup,” Westerly Magazine 54:1 (2017), 77. See also Julie Marcus, “‘…like an Aborigine’: Empathy, Elizabeth Durack, and the Colonial Imagination,” Bulletin (The Olive Pink Society) 9:1 an2 (1997), 44-52.

[22] O’Connell, Kylie. 2001. “‘A Dying Race’: The History and Fiction of Elizabeth Durack.” Journal of Australian Studies 25 (67): 44–54.

[23] Robert Smith, “The Incarnations of Eddie Burrup,” Art Monthly Australia, no.97, March 1997, 4-5.

[24] John Paull, “The Incarnation of Eddie Burrup: A Review of Elizabeth Durack, Art & Life, Selected Writings,” Arts 6:2 (2017), 7.

[25] National Film and Sound Archive of Australia: “Australian Biography: Elizabeth Durack,” 1997.

[26] Nolan, “Elizabeth Durack,” 137

[27] McCulloch, “What’s the fuss?”, 18.

Leave a Reply