A Political Philosophy of Moviegoing?

by Scott Dill

~

While on a flight back to New Orleans, Binx Bolling, the protagonist of Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer, studies a young man who is reading The Charterhouse of Parma. Binx is curious to learn how he sits, “Immediately graceful and not aware of it or mediately graceful and aware of it?” The apparently innocent matter of posture becomes another sign in what Binx calls his “search.” Soon enough Binx concludes in disappointment that his fellow passenger is “mediately graceful” as well as “a romantic.” Because he is reading Stendhal? No, because his mere comportment is so deeply mediated with melancholy self-awareness. “The poor fellow,” Binx reflects, he “has just begun to suffer from it, this miserable trick the romantic plays upon himself: of setting just beyond his reach the very thing he prizes.” His desire will forever pant, but never be fulfilled. To sum up this desperate relationship to desire Binx comments, “He is a moviegoer, though of course he does not go to movies.” Moviegoers have enshrined a popularized form of romantic longing, Percy suggests, centuries after the height of Romanticism. Yet movies offer no innocent frolic among the wildflowers of poesy; for Binx, movies are a capitalist culture’s most exhaustive method of mediating the romantic individual’s desire. One need not even go to movies to be a moviegoer, so pervasive are their effects on the cultural imagination. This diagnosis of the moviegoer’s susceptibility, and subsequent unhappiness, captures Percy’s persistent critique of late twentieth-century American individualism—that its short-circuited self-knowledge cannot sustain a thriving culture.

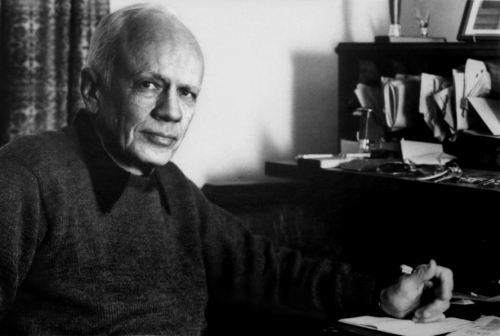

A new edited collection of essays begins the important work of teasing out the various implications of Percy’s view of the individual for political thought. If the individual is finally unintelligible to himself, what does this imply for the politics of liberal individualism? A Political Companion to Walker Percy, in keeping with the intentions of the Political Companions to Great American Authors series at the University Press of Kentucky, seeks to elucidate Percy’s major contributions to a long, if not august, American tradition of belletristic political writing. For example, the volume’s final essay juxtaposes Percy’s twentieth-century vision of American society alongside of Alexis de Tocqueville’s from the nineteenth. The surprising foil flatters both writers. Yet, even more propitious, A Political Companion to Walker Percy evinces an admirable thematic coherence for a collection of critical essays. Editors Peter Augustine Lawler and Brian A. Smith’s introduction begins with the question: “Why do two political scientists say that an American Catholic novelist can teach us what nobody else can about our nation’s political life?” Though perhaps overstated, it sets the problem each essay shares, even if their topical concerns vary. Lawler and Smith’s answer is that the various ideologies Percy found plaguing our national political life—racism, the reductions of scientism, radical individualism, the ideal of stoicism—are best elucidated by Percy’s unique “indigenous Thomism.” Percy’s “indigenous Thomism” is, according to Lawler and Smith, a neglected but crucial strain of American political thought.

The harmonization of what we know through science and what we know through revelation is the rather distinctively Catholic project called Thomism. There’s a neglected American Catholic tradition composed of Orestes Brownson (author of The American Republic, 1865), John Courtney Murray (We Hold These Truths, 1960), and Percy that holds that a Thomistic interpretation of the greatness of our Founder’s accomplishment is the gift American Catholics can offer their country.

It is the gift of this volume to place Percy in such a tradition. Rather than dealing with Percy exclusively as a Southerner, Lawler and Smith place his thought in a national conversation stretching back to Brownson’s dissenting stand against the rugged individualism of his Transcendentalist contemporaries. This more ambitious, if not more appropriate, placement of Percy’s political thought is due to their view that Thomism offers America “a better foundation for its liberalism than that our nation’s most prominent political philosopher’s have provided us.” A curious claim, but then again, Percy himself loved to provoke.

The argument that Catholic theology provides the key conceptual grounding for a distinctively American liberalism refrains from any legislative prescriptions in these pages. It is rather an argument about what constitutes the best soil for cultivating genuine human flourishing. The editors are quick to point out that Percy does not intend “to politicize the church” and more than he hopes “to have public policy animated by the personal virtue of charity.” His writing does, however, “show how our political life is limited and sustained by who we are as truthful, social, personal, joyful, and loving beings.” Lacking clear political prescriptions, they see Percy’s work as providing a philosophy of personal relations. For the individual is fundamentally social in Percy’s work. An essay by Nathan P. Carson explains Percy’s writing on semiotic theory in light of his convictions about communal virtue. What is often treated as an abstract theory of signification or a rarified problem in the philosophy of language becomes in Percy’s work the grounds for a virtue ethics—semiotics cum communitarianism. Carson concludes that Percy’s “conjunction of the ontological joys of scientific and philosophical inquiry, on the one hand, and radical dependence, other-regard, and community, on the other, is a refreshing and rare combination.” Several of the essays here collected unfold Percy’s conviction that neither language nor the individual can make any sense outside of the communities in which they are formed.

Lawler and Smith’s answer is that the various ideologies Percy found plaguing our national political life—racism, the reductions of scientism, radical individualism, the ideal of stoicism—are best elucidated by Percy’s unique “indigenous Thomism.”

Farrell O’Gorman gets past the isolating idiosyncrasies of Percy’s at times bizarre novels in “Confessing the Horrors of Radical Individualism in Lancelot: Percy, Dostoevsky, Poe.” First, O’Gorman traces the formative influence that reading Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground had on Percy as he composed Lancelot. Both books “were created by authors who embrace traditional Christianity but utilize obsessive and intentionally offensive post-Christian narrators who simultaneously critique and personify what the authors see as the horrors of the radical individualism engendered by modernity.” If Percy lifted much of the structure of his novel’s critique of individualism from Dostoevsky’s acrimonious narrator, its generic roots stretch down deeper into American soil. In a deft revision of Edgar Allan Poe’s place in gothic fiction, O’Gorman shows how Percy’s time with Allen Tate and Tate’s writing on Poe influenced Percy’s use of gothic tropes, particular its figuration of the female body. O’Gorman argues that the gothic novel emerged from an eighteenth-century moment when a culture “that increasingly valued a self-reliant and essentially disembodied but figuratively masculine rationality sought in effect to exorcise its Catholic past.” He then traces Percy’s reading of Poe to show how the body remains a stubborn stay against the idealized rationality assumed in radical individualism. Rather than celebrate the “American Adam,” the masculine mind free from the gothic past’s figural femininity, Percy represents forms of embodiment that return to and revise the Catholic past so ashamedly disavowed earlier in the gothic tradition.

“Radical individualism,” as here construed, is a threat to the very ideal it commends. Other threats to the liberal individual covered in these essays range from the moviegoer’s “Cartesian theater” to the collective consequences of pursuing happiness to the politics of love and marriage to the reductionist views of scientism. In “Walker Percy’s Alternative to Scientism in The Thanatos Syndrome,” Micah Mattix explicates the relationship between Percy’s semiotics and his view of the novel’s unique cultural work. As opposed to merely descriptive accounts of language, Mattix shows how Percy’s conviction that language is ontologically efficacious—that is, that words are essentially connected to actualities—informs his robust view of the novel. Novels do the moral work of accurately naming the social relations that compose human life. Writing novels, in restoring the moral burden of language, restores the possibility of genuine community.

Percy’s moral commitments are not left alone to collect dust up on the shelf of theory. Brendan P. Purdy and Janice Daurio contribute an essay on the evolution of Percy’s personal views on race relations in the South. “The Second Coming of Walker Percy: From Segregationalist to Integrationist” documents the three strands of Percy’s thought that developed in the forties and informed his 1956 Commonweal article, “Stoicism and the South” (published four years prior to his debut novel, The Moviegoer). To Percy’s treatment of the stoicism he saw represented in the work and life of his famous uncle, William Alexander Percy, they add his reading of Kierkegaard, C.S. Pierce, and his conversion to the Catholic faith. Connecting Percy’s religion with his ethics and his politics, Purdy and Daurio best capture the spirit animating Percy revealed in this volume, “Being a Christian is not a matter of becoming one more political party; it is being formed as a person of a certain sort who brings the vision of who he is to his decision about what he does.” Percy’s Catholicism does not determine allegiance to a political party, but offers a political philosophy of the person that is also necessarily an ethics. To be formed as a person whose identity governs his or her actions is precisely what Percy’s Thomistic vision finds missing in the American polis.

His writing does, however, “show how our political life is limited and sustained by who we are as truthful, social, personal, joyful, and loving beings.”

As unified as these essays are in their exposition of Percy’s thought, a growing silence begins to clamor between the lines of A Political Companion to Walker Percy. While many of its chapters refer to Percy’s view of sacramental mediation, not a single one addresses the kinds of cultural forms that Percy despaired of too thoroughly mediating desire, such as movies or self-help books, and the conventions of the capitalist society in which they thrive. Percy’s indignation that the remnants of an ill-fated Christendom condone the economic structures of solipsistic individualism is largely ignored. This is a shortcoming insofar as it shows the volume’s tendency to pigeonhole Percy as yet another conservative Christian from the South. But Percy’s critique of Christendom is wide-ranging, especially when it comes to what Eugene McCarraher has memorably called “Chrapitalism,” “the lucrative merger of Christianity and capitalism, America’s most enduring covenant theology.” Percy’s work is never without an overwhelming awareness of the crippling effects of baptized consumerism and corporate greed. The flows of capital responsible for enshrining moviegoing as a way of life emerge from real institutions that can and should be fixed. A devout Catholic, Percy was no Chrapitalist.

In his study of contemporary fiction, Partial Faiths: Postsecular Fiction in the Age of Pynchon and Morrison, John McClure traces the surprisingly frequent coalescence of religious and political economies in late twentieth-century American fiction. In what McClure calls the “age of Pynchon and Morrison,” into which Percy lodges squarely, a swath of novels portray new political formations, communities of “preterite spiritualities and neomonastic politics” that put into practice a “politics of engaged retreat.” Of Thomas Pynchon and Don DeLillo’s novels McClure writes, “Scorning the codes of theological order and exclusivity that characterize ‘high’ religious traditions, they develop modes of thought and practice that are scandalously impure.” Both Love in the Ruins and The Second Coming offer images of precisely such an “impure” community, as does the “engaged retreat” modeled on Dostoevsky’s underground man in Lancelot. Percy’s work certainly fits into McClure’s account of a neo-monastic politics. Like Alastair McIntyre’s call for a figure amalgamating Trotsky with St. Benedict, or Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s call for a new St. Francis of loving renunciation, Percy’s work longs for a new economic structure of more fulfilling affective resonances. Lawler and Smith’s collection has managed to wrench Percy free from purely regional concerns, but it is too content with the political limitations of red state/blue state quibbles. This book, which contains an essay by Richard M. Reinsch III that argues, “the South’s evangelicalism might […] demonstrate an alternative to the highly secular model blue states present,” suffers from a limited reading of Percy’s political imagination. Percy’s suspicion of the illusions of a left-right dichotomy, served up as the ridiculous feuds of the Knotheads and LEFTPAPASAN in Love in the Ruins, makes such crass correlations dubious, if not scurrilously narrow-minded. As helpful as this collection is in rethinking Percy’s politics, it has yet to come to terms with the vicious bite of this justly lionized Southern Catholic.

__________

Scott Dill is a PhD Candidate in the Department of English at UNC Chapel Hill. He is currently writing his doctoral dissertation on formal representations of the secular in contemporary American novels.

Leave a Reply