by Tanya Agathocleous

A work of the political imagination rhetorically designed to reach beyond its local context and history, Jyotirao Phule’s anti-caste pamphlet “Slavery” might be seen as an ideal test-case for the strategic presentism of V21 methodology, insofar as this aims to draw formal connections across historical contexts and national traditions while highlighting the political urgencies that connect past and present.

Phule, a reformer who campaigned for lower caste and women’s rights, first published “Slavery” in 1873 in Marathi, along with an English preface that highlighted its central argument. Now considered a foundational text of the Dalit movement, “Slavery” was impactful because of its revisionist understanding of caste as a system of exploitation rather than religion or biology, and the ways it used this insight to lay the groundwork for transnational solidarities by drawing connections among caste in the Indian context, British colonialism, and American slavery.

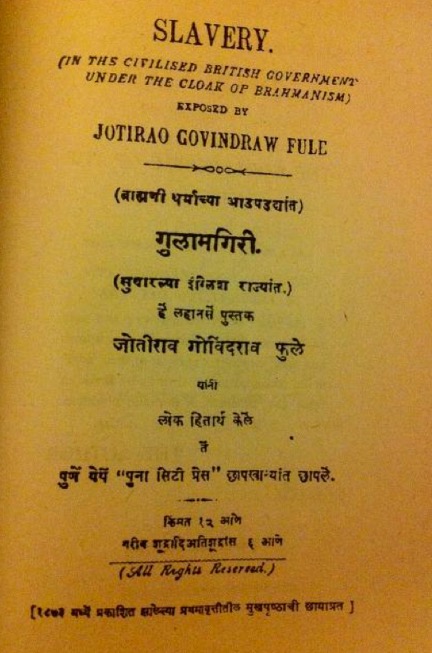

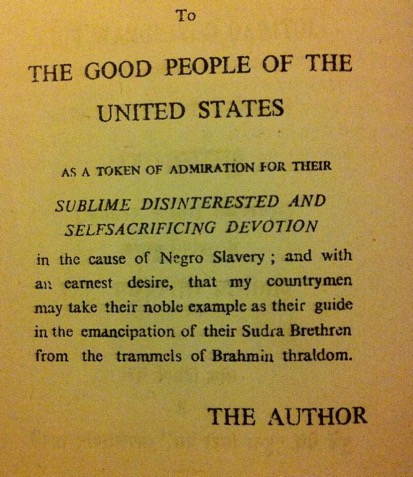

The pamphlet’s use of two languages underscores its desire to speak across national contexts. Its full title, “Slavery (in the Civilized British Government under the Cloak of Brahminism),” links the caste system to colonial exploitation, while a dedication on the title page makes a further connection to America’s recent civil war and abolitionism: “To the good people of the United States as a token of admiration for their sublime disinterested and self-sacrificing devotion in the cause of Negro Slavery; and with an earnest desire, that my countrymen may take their noble example as their guide in the emancipation of their Sudra Brethren from the trammels of Brahmin thralldom” (Phule, 1873: 25).

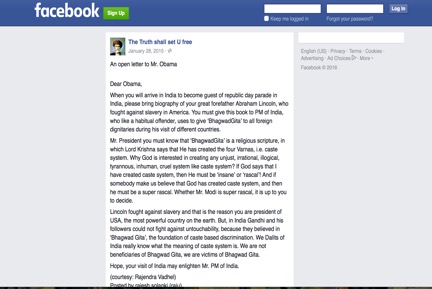

The success of its strategy of linking these different contexts is evidenced by the enduring appeal of this type of rhetorical gesture and of the pamphlet itself. On the occasion of his 2010 visit to India, for example, U.S. President Barack Obama was presented with a copy of Phule’s influential work. The politician who bestowed it upon him, Chhagan Bhujbal, was at the time Minister of Public Works for the state of Maharashtra and an activist in the Dalit movement. His act was one of the more direct appeals to the U.S. President made in Phule’s name during his Indian visit, but there were more indirect and informal ones as well, in the form of “open letters” and appeals posted on Indian blogs and social media sites. One of these, a Facebook page named “Mahatma Jyotirao Phule hardcore fans,” displayed a letter to Obama that asked him to give a biography of Lincoln to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi as a preemptive response to Modi’s habit of bestowing the Bhagavad Gita upon visiting dignitaries. Labeling themselves victims of the Hindu religious text, historically used as a rationale for caste hierarchies, the authors of the open letter call upon Obama to enlighten Modi via Lincoln, and to look upon both the Bhagavad Gita and Modi’s politics with suspicion (see https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?id=604902749582245&story_fbid=796515553754296).

While Obama might seem an unexpected addressee for a local group of Dalit activists in India, their gambit in posting the letter makes sense in light of the historical import of Phule’s pamphlet. Though separated in time by almost a century and a half, Phule’s work and the Phule fans Facebook page operate similarly, for both address the U.S. in order to “jump scale” from the national to the international stage with the goal of embarrassing local leadership and drawing wider attention to the inequities of India’s caste system.[i] Both denaturalize this system by associating it with racial injustice in a starkly different national context while creating a narrative of progress in which this injustice might be defeated: the North’s victory in the Civil War and Obama’s victory against American racism as the first black president are invoked as signs that the U.S. might serve as a model for overcoming structural inequity in India. In these parallel examples of Afro-Asian solidarity, transnational comparison is used both to suggest new forms of alliance across national and historical contexts and to undermine essentialist understandings of race and caste.

In recent work on the history of pre- and post-Bandung politics, critics have argued that this type of transnational comparative move relies on an over-simplification and idealization of one context in order to advocate for change in the other; in both these cases, for example, U.S. racism post-Civil War to the present is overlooked by the Indian writers so that American racial history might be seen as exemplary.[ii] I suggest, however, that we might think differently of the form and function of this kind of comparison. Rather than seeing Phule and the Facebook page authors as naïve interpreters of American history, which they were unlikely to be given their respective contexts, we might see them as canny authors of a kind of counterfactual history. In reading the outcome of the Civil War and Obama’s presidency as if they might serve as unmitigated instances of racial justice, they create a utopian narrative paradoxically rooted in the real world, albeit at a hazy distance—a new American past that might serve as inspiration for a new Indian future.

Bringing to light what Lisa Lowe calls “the intimacy of four continents” in its linking of slavery, empire, and caste across space and time, Phule’s text travels from nineteenth-century Maharashtra through the twentieth century—inflecting the vocabulary and goals of Afro-Asian political alliances along the way—to be put directly into the hands of its ideal interlocutor as an uncanny object: one that throws into relief the twisted historical logic that made Obama, in 2010, at once a metonym for the history and transcendence of American slavery and for the neoimperial world order.

References

Burton, Antoinette. 2012. Brown Over Black: Race and the Politics of Political Citation. Delhi: Three Essays Collective.

Phule, Jotirao. 1873. “Slavery” In Selected Writings of Jotirao Phule, edited by G.P. Deshpande. Delhi: LeftWord Books (2002).

Slate, Nico. 2012. Colored Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom in the United State and India. Boston: Harvard University Press.

Notes

[i] The idea of “jumping scale” is taken from Neil Smith’s essay, “Contours of a Spatialized Politics: Homeless Vehicles and the Production of Geographic Scale” Social Text 33 (1992): 54-81. Smith defines “jumping scale” as the practice of dissolving “spatial boundaries that are largely imposed from above and that contain rather than facilitate (the) production and reproduction of everyday life” (60). I are grateful to Stéphane Robolin for drawing our attention to the usefulness of the term for describing the interventions of colonial subjects at events like the URC through his analysis of John Tengo Jabavu’s work there in a paper given at the Universal Races Congress of 1911 Symposium at Rutgers University in 2015.

[ii] See, for example, Nico Slate, Colored Cosmopolitanism and Antoinette Burton, Brown Over Black: Race and the Politics of Political.

CONTRIBUTOR’S NOTE

Tanya Agathocleous is Associate Professor of English at Hunter College, CUNY. She is the author of Urban Realism and the Cosmopolitan Imagination (Cambridge UP, 2011), and is currently editing the new Penguin edition of Great Expectations.

Leave a Reply