This essay is a part of the COVID-19 dossier, edited by the b2o editorial staff.

by Belinda Kong

In the penultimate chapter to Minor Feelings, Cathy Park Hong (2020) pays belated homage to Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. “For a while,” Hong writes of her own development as a poet, “I thought I had outgrown Cha. I’d cite modernist heavyweights like James Joyce and Wallace Stevens as influences instead of her. I took her for granted. Now, in writing about her death, I am, in my own way, trying to pay proper tribute” (171). In researching Cha’s life, Hong was perturbed by the silence around her death. Though Cha is a canonized figure within Asian American literature with much critical attention devoted to her experimental novel Dictee, Hong found to her surprise that “no one wrote anything about the crime” around Cha’s death (155). Cha was raped and murdered in November 1982, in the sub-basement of Manhattan’s historic Puck Building, newly acquired by Kushner Properties and undergoing renovations at the time. Her killer was a serial rapist who worked as a security guard there, hired simply because “he knew English.” Cha, on the other hand, was initially called “an Oriental Jane Doe” in the police report (164-65). This was a week after the publication of Dictee. Those who have written on Cha’s work but circumvented the subject of her death cited the desire to protect her family and to avoid reducing the significance of the former to the sensationalism of the latter. But what Hong discovered, when she contacted Cha’s relatives and friends, was that they were eager to talk. “Why hadn’t anyone reached out to Cha’s relatives earlier? Why hadn’t anyone looked at the court records?” she muses. “They’re not hard to find. In fact, they’re readily available online….” (172).

*

In researching the 2003 SARS global epidemic and the cultures of epidemic life that sprang up at its epicenters, I found myself on a parallel path as Hong but walking it in reverse. I too began by looking at literature and culture, at novels and then, more adventurously, films and digital media, partly because those realms constitute my relative comfort zone as a literary scholar, but mostly because I assumed that the history and real-life stories would have been told by others before me. I first started researching SARS around 2014, over a decade after the epidemic’s end, so I took it on faith that the facts were well-documented in the voluminous body of writing already published on the topic, and that even early cases in mainland China and Hong Kong would have been properly archived by then. Moreover, since English, as the World Health Organization itself acknowledges, remains the dominant language of global public health information and “the lingua franca of scientists—including those working in public health” (Adams and Fleck 2015: 365), I also took it on faith that knowledge about specialized epidemiological matters such as index cases and early outbreak clusters would be firmly in place in the anglophone public record. In short, I took the epidemic’s first patients and their stories for granted, as things that were already told and known, things that I did not have to bother to investigate for myself. I was content to stay in my disciplinary lane and focus on fictional texts and fictional lives, venturing into historical and empirical sources only for context and self-education. It took several years of writing and reading, until the last chapter of my book project, for me to fully realize my misplaced faith.

What I discovered, when I started digging into accounts of the global index patient, was the opposite of what Hong observed with Cha: that much has been written on this Chinese patient’s death but not his life—even though he did not die. If the story of Cha’s death is full of gaps and silences, those of SARS’s first patient are chockfull of inaccuracies, distortions, and prejudices.

*

If one were to do an internet search on SARS in English today, one of the top hits would likely be the Wikipedia entry on “Severe acute respiratory syndrome” (2020b). There, under the section “Epidemiology,” under the first subheading “Outbreak in South China,” the disease’s animal and human origins are narrated as follows:

The viral outbreak can be genetically traced to a colony of cave-dwelling horseshoe bats in China’s Yunnan.

The SARS epidemic appears to have started in Guangdong, China, in November 2002 where the first case was reported that same month. The patient, a farmer from Shunde, Foshan, Guangdong, was treated in the First People’s Hospital of Foshan. The patient died soon after, and no definite diagnosis was made on his cause of death.

A separate Wikipedia entry on “2002-2004 SARS Outbreak” (2020a) offers this companion timeline and profile:

On 16 November 2002, an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) began in China’s Guangdong province, bordering Hong Kong. The first case of infection was traced to Foshan. This first outbreak affected people in the food industry, such as farmers, market vendors, and chefs. The outbreak spread to healthcare workers after people sought medical treatment for the disease.

Other websites on the anglophone internet, not surprisingly, have replicated this narrative over the past decade, sometimes verbatim (see Zolli 2012; WordPress 2013). In the months of COVID-19, anglophone news outlets spanning the US, the UK, Europe, and Asia have retrospected on SARS by repeating this very story of its first index case as an anonymous dead farmer from Foshan, Guangdong (see Martin 2020; Moura 2020; Ma 2020; Gopalan 2020; Nelson 2020; Stanley 2020). Given the widely accepted thesis on the zoonotic origins of SARS, readers are left to connect the dots between the coronavirus’s animal hosts and the rural farmer who first contaminated himself by living in proximity to them. In line with what anthropologist Mei Zhan (2005) highlighted in international media coverage of SARS in 2003, the dead farmer story subtly implies a “deadly filthiness” to Chinese “strange entanglements of human and animal bodies” (37).

Nor is this narrative restricted to online sources. Print references to SARS’s primal farmer have long appeared in English-language scientific and academic venues, from a 2005 Pediatric Annals article on animal viruses (Lee and Krilov 2005: 43-44) to a 2006 Urban Studies journal article on infectious disease and global cities (Ali and Keil 2006: 497) to a 2007 Lancet book review of a McGill-Queen’s University Press anthology on SARS (Bugl 2007: 710). By now, the notion that the world’s first SARS patient was a Foshan/Guangdong farmer has entered into anglophone pandemic lore, dispersed across, among other things, a virology textbook (M. Taylor 2014: 386), a guide on sustainability and corporate responsibility (Kao 2010: 113), a crisis management reference work (Penuel et al. 2013: 771), a mathematical engineering study (Hu et al. 2016: 1), a political science analysis (Wang 2018), as well as myriad mass market books on climate change, emerging viruses, and pandemic outbreaks (Marsa 2013: 46; Zimmer 2015: 85; Khan and Patrick 2016: 165). Even Ali Khan, the former director of the US CDC Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response, affirmed this version of events in his book The Next Pandemic (2016):

The official narrative for the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak that swept through Asia and grazed North America traces the first reported case to Guangdong Province, China. This was mid-November 2002, and the patient, a farmer, was treated in the First People’s Hospital of Foshan, and then promptly died. (165)

What further unites all these anglophone sources is the allegation, sometimes explicit, other times strongly insinuated, that the farmer not only infected himself and those around him but initiated a nuclear chain infection that ultimately culminated in a catastrophic global epidemic.

*

The problem with this “official narrative,” however, is that it is replete with egregious errors and orientalist biases. In reality, SARS’s first known patient was not a peasant farmer, he was not at the center of an explosive outbreak cluster, he did not kill anyone, and above all, he did not die from the virus. In reality, he was an elected local official with an administrative office job, he directly infected only two family members but no healthcare workers, this was a contained cluster with five infections total and no fatalities, and he lived on to tell his tale even ten years later.

*

His name is Pang Zuoyao. In November 2002, he was the deputy chief of Bitang Village. Though labeled a village, Bitang was in fact a thriving industrial town in the heart of Foshan, a city of three and a half million (approximately the size of Los Angeles). “The people in this village are quite wealthy,” according to migrant workers who came here looking for factory jobs, “and you can earn a lot just with annual bonuses” (quoted in Wu and Li 2013). Pang’s was an elected position, one that he would continue to hold for at least another decade. At the time, he was also assistant chair of the local shareholding economic cooperative (Wu and Li 2013). By the early 2000s, most local enterprises had been privatized, so Pang’s work consisted mainly of managing real estate and sometimes overseeing family planning issues (Hu and Ma 2006). He was relatively well-to-do, living with his wife and four children in a four-story house (Leu 2003a). His oldest son was applying for college that year, his daughter was about to enter high school, and his youngest child was a fifth-grader-to-be (Zheng, Wang, and Chen 2003). By all indications, he was a low-level government cadre leading a comfortable middle-class life in China’s liberalizing economy.

It was also this set of personal circumstances that afforded Pang and his family access to advanced healthcare and that led to their surviving SARS. On November 16, Pang developed a high fever, headache, dry cough, and weakness and was rushed to the hospital closest to his house, the second-tier Shiwan People’s Hospital. After nine days, his fever persisted, so he was transferred to the top-tier Foshan No. 1 People’s Hospital. There, he was promptly admitted to the isolation ward and then transferred to the intensive care unit, where he was put on a ventilator—all treatment options available only to those with financial means (Zheng, Wang, and Chen 2003; Hu and Ma 2006; Wu and Li 2013). Throughout that period, Pang’s family visited him at the hospital every day, and since no one knew to take precautions, he infected both his wife and his maternal aunt, and the latter in turn infected her husband and daughter. All five family members were hospitalized, but in the end, all recovered, and Pang himself was discharged on January 8, 2003 (Zhou et al. 2003: 599; Xu et al. 2004: 1033; Zheng, Wang, and Chen 2003; Hu and Ma 2006). None of his children at home caught the virus, nor did any of his Bitang neighbors or any hospital worker who cared for the family. According to two early epidemiological studies on SARS, this Foshan outbreak, the first one known to us, was an intrafamilial cluster with only five patients, and the transmission chain ended there (Zhou et al. 2003: 598; Xu et al. 2004: 1033). So, despite being SARS’s first known cluster, it was not the spark that ignited a global infection chain. As one of Pang’s physicians commented afterward, this case could be considered a “miracle” (quoted in Zheng, Wang, and Chen 2003).

Later on, Pang would be identified as the world’s first known SARS patient, the epidemic’s global index case. At the time, though, no one knew this was a new virus, least of all Pang himself. Even the ICU director at the Foshan hospital who oversaw Pang’s case remembered calling it simply a “respiratory infectious disease of unclear cause” (quoted in Hu and Ma 2006). Pang was never formally diagnosed with SARS, and in fact, according to his wife, the hospital’s initial diagnosis was food poisoning (Leu 2003a).

Pang’s own processing of the experience was protracted and traumatic. A few months after his discharge, after the coronavirus had been identified and as the epidemic raged worldwide, Pang and his family still found it hard to believe that what they had suffered was SARS. “I don’t even know if I am related to what happened elsewhere,” he told Ching-Ching Ni, a staff writer for Los Angeles Times, over the phone in April 2003. “The day I left the hospital, they said they didn’t know what I had” (quoted in Ni 2003). Likewise, Mrs. Pang told South China Morning Post journalist Leu Siew Ying in person that same month, “I find it baffling [that people say we had SARS] because no one in my family has the illness. My husband’s parents and his seven siblings and my parents and my own four siblings spent time with him during the day or visited him regularly. None of them fell sick.” Pointing to the town traffic, she speculated, “I think it is the air pollution that is making us ill” (quoted in Leu 2003a). To reporters from the province’s 21st Century Business Herald, Mrs. Pang pleaded, “[My husband] is very busy with work, and he has a stress prone personality … so please don’t bother us anymore” (quoted in Zheng, Wang, and Chen 2003). Another few months later, Pang himself remained terse with reporters both domestic and foreign. “I have completely recovered,” he declared to Leu on her follow-up visit, with an emphasis on recovery that had become a refrain for him. “If you are concerned about sick people go to the hospitals. You are wasting your time with me” (quoted in Leu 2003b). “Let the past be the past,” he implored the journalists from Guangzhou’s Southern Weekend who tracked him down in 2006. More resigned now to the SARS diagnosis, he told them, “I don’t want to think about it anymore. I myself have no idea why I caught SARS. When I got sick, there wasn’t yet the term ‘atypical pneumonia.’ Properly speaking, I was only retroactively labeled a SARS patient” (quoted in Hu and Ma 2006). One oft-cited comment by the respiratory specialist and “SARS hero” Zhong Nanshan is that 96% of mainland China’s SARS patients had no clear contact history, so for them, the whole episode was like “bafflingly having a nightmare” (quoted in Yang 2012). For Pang especially, the virus must have struck like something utterly out of the blue, supernatural and uncanny. And if the disease itself left, the stain of it lingered, branding him the world index case—a designation he had no power to reject. He had little time to narrate the experience for himself and to give it personal meaning before the external world descended to take over his story.

*

For much of the decade after the epidemic, Pang kept a low profile, dodging all media attention (Wu and Li 2013). For a period that summer, his family even vacated their Bitang house and went into hiding (Blackwell 2003). What little we know of his actual post-SARS life comes from a handful of articles based on the few interviews he and his family granted over the years, primarily to reporters from southern China. One significant impact of the disease episode on him and his family, as he related to Southern Weekend, was economic. The medical bills for his family had come to 400,000 yuan (almost $60,000), a not insubstantial sum for a village-level official, even a well-off one like Pang. “At the time I thought, out of nowhere came this strange disease, and just like that, 400,000 yuan gone. What a waste,” he said. “But then I thought, if you lose your life, what’s the point of mourning the loss of money?” (quoted in Hu and Ma 2006).

Indeed, SARS had a deep and lasting impact on Pang’s lifestyle and value system. In the half-year following his hospitalization, he remained physically weak and would gasp for breath after climbing a few flights of stairs (Hu and Ma 2006). He became much more health conscious as a result, quitting smoking and giving up alcohol, taking up regular tai chi and long-distance jogging instead. He also stopped dining out, and every day at noon, he unfailingly drove home from work to eat a lunch prepared by his wife, meticulously washing his hands before every meal (Yang 2012). Ten years on, he kept up these habits. Now in his mid-fifties, he continued to serve as Bitang’s deputy chief. As he remarked to a reporter from Blog World in 2012, “I take my work seriously every single day, and I intend to work hard until my retirement. If there’s a change in me, it’s that I give greater importance to health and family now” (quoted in Yang 2012). SARS also made him more fastidious about hygiene. Two reporters from the Information Times noted in 2013 that, after receiving guests in his office, Pang would wash all the cups by hand and then sterilize them in a disinfecting cupboard next to the sofa (Wu and Li 2013). All these routines grew out of Pang’s brush with SARS, the small residual effects of his disease experience and the enduring transformations of his everyday life thereafter.

At the same time, these self-care practices may have embodied Pang’s coping mechanisms for the physical trauma of the ordeal and its various side effects. One Hong Kong study (Lee and Wing 2006) found that 45% of recovered SARS patients developed one or more mental illnesses within three weeks of discharge: 13% suffered from organic mood syndrome, 11% from major depression, 11% from adjustment disorders, 7% from PTSD, 5% from generalized anxiety disorder, and 2% from transient delirium or psychosis. Those who had been in ICU had a higher likelihood of developing one of these illnesses, and many survivors additionally “complained of profound lethargy and disturbing forgetfulness” (144). There is no public record of Pang ever seeking professional therapy, but the person who emerges from these published accounts fits the profile of someone struggling with posttraumatic stress.

In his case, disease survival was compounded by the stigma of being the world index case. When the WHO investigative team to Guangdong visited Pang’s house in April 2003, word got out and “it was clear to everyone in his neighborhood that it was him,” according to Robert Breiman, the leader of the WHO team. “He told me that this created many problems” (quoted in Ang 2003). As some of Pang’s neighbors admitted to reporters later that summer, “At first, we didn’t know who [the SARS patient among us] was. After we knew that he got SARS, we didn’t want to have any connection with him” (quoted in Blackwell 2003). Years later, the family still remembered how their neighbors gossiped and blamed Pang for unleashing a global plague. In one workplace dispute, Pang’s SARS record was brought up against him, an incident that put him on guard ever after for political rivals weaponizing his disease history against him (Yang 2012). In the post-SARS decade, then, Pang rarely spoke of his medical past and hid it from most coworkers, even deliberately distancing himself from the doctors and nurses who had treated him and his family. His attending physician at the time sympathized with this evasion: “Foshan people are very practical and low-key. Besides, this isn’t something anyone would want to grab the limelight for,” the doctor commiserated (quoted in Wu and Li 2013). Over time, to Pang’s longtime colleagues and relatives, it seemed as if SARS never happened, as if it had been wiped clean from his memory, whether by design or repression (Yang 2012). These, then, were also things that lived through SARS and trailed Pang for years: ostracism and stigma, uncertainty and suspicion, forgetting and self-silencing.

Perhaps what gnawed at Pang the most was the accusation, and the possibility, that his own dietary habits did in fact cause a new deadly human virus. Like many of his neighbors, Pang used to enjoy eating wild animals, or yewei. About a month or so prior to falling sick, he had traveled with a friend to Guangxi Province and brought home some game meat (Zhou et al. 2003: 598; Wu and Li 2013). And about a week before his hospitalization, he had dined on “wild cat meat” with a friend twice and again brought some home for his family (Zhou et al. 2003: 598; Hu and Ma 2006). During that period, he also prepared meat dishes at home, including “chicken, domestic cat, and snake” (Xu et al. 2004: 1033). But, significantly, none of those who shared these meals became infected. “My husband ate mutton and cat meat before he fell ill,” recalled Mrs. Pang. “He said cat meat was good for his backache, so sometimes he has cat meat outside and sometimes I cook it at home. Most people here eat cat meat, but nobody has SARS” (quoted in Leu 2003a).

What no media report mentions is the possible sociohistorical link between Pang’s generation and the contemporary trend of wildlife banqueting. Being forty-five in 2002, Pang would have been born around 1957, a year before the start of the 1958-61 Great Famine. Mrs. Pang was forty-two in 2002, so she would have been born in the middle of the famine years, around 1960. While we do not know whether they or their families suffered from starvation during those winters, a history of hunger and mass death defined much of the national landscape of their infancy, especially in rural areas. Without pathologizing either the Pangs or their generation, we can nonetheless conjecture, following Judith Farquhar’s (2002) “anthropology of the mundane,” that commonplace bodily appetites can register collective historical experiences and postmemorial traumas. In the case of postsocialist China, Farquhar suggests, acts of eating often operate within “a politics of restitution in which people are intent on ‘getting rich’ (facai zhifu) and ‘enjoying themselves’ (zhaole) as a way of making up for the poverty and misery many associate with their collective history” (129). Thus, consumption practices in the reform era, particularly by the rising urban middle class, often entail an ethical calculus tied to Maoist history, whereby eating itself becomes a set of economic and historical reckonings about “excess and deficiency”: “How much enjoyment or bulk is justifiable for the fortunate in a world where starvation is all too real for some of their neighbors? Is there value in ‘high’ civilization (gourmet food, for example) if many of the socially ‘low’ have no access to its sophisticated pleasures? Can past famine justify indulgence in present and future gluttony?” (122).

The Pangs and their appetites, too, would have emerged from this history, with SARS as the latest event in an ongoing national dialectical grappling with lack and surplus. Maybe, to some degree, the epidemic interrupted their psychohistorical reliance on that calculus and helped redefine well-being from endless consumption to equilibrium upkeep. In any event, the Pangs abandoned their wildlife diet after their infection, opting instead for healthy dishes such as plain steamed fish (Yang 2012). According to their daughter, though, Pang never accepted the zoonotic thesis about SARS, despite mounting scientific consensus. In the ten years after, he never ceased searching for an alternative cause for the coronavirus. Like his wife, he pointed to environmental factors such as industrial pollution as the root of his illness. He often suspected that the exhaust gas from a funeral parlor near his workplace was the true culprit, and he repeatedly campaigned to have the funeral parlor relocated, even enlisting for help the press he so avoided otherwise (Yang 2012). This, too, merits consideration as a small act of local eco-activism, as epidemic experience bred skepticism toward the state’s economic development goals and an awareness of the human reverberations of environmental contamination.

*

I patch together this reconstruction of Pang Zuoyao’s story in order to highlight that, even for its global index patient, SARS infection and survival can be narrated in the terms, not of perpetual emergency and pandemic crisis, but of ordinary resilience. Medical authorities and experts might reach for the magical or the occult to explain the scientifically inexplicable aspects of SARS and Pang’s case—a “miracle,” a “nightmare”—but Pang himself seemed to want nothing more than a restoration of the normal and the prosaic. Elsewhere, I have analyzed Wuhan writer Hu Fayun’s 2004 novel Ruyan@sars.come (Such Is This World@sars.come) through a framework I call pandemic ordinariness (see Kong 2018). Not so unlike Hu’s eponymous protagonist Ru Yan, Pang lived beyond SARS by turning to aspects of his domestic life that allowed for small and everyday agency, such as quitting risk-raising old habits and initiating new self-nourishing routines. Indeed, his reformed lifestyle resonates with western biomedical paradigms that emphasize personal health regimens such as diet, nutrition, and exercise. In the process, he reoriented himself away from the raw accumulation of economic, political, and social capital toward bodily self-care and familial preservation. These mundane changes in Pang’s daily life did not carry any noticeable impact on the national or global stage, nor did they amount to any grand gestures of resistance. As a whole, Pang’s story does not lend itself so easily to either prefabricated cautionary tales of disastrous contagion or geopolitical critiques of communist totalitarian biopower. In a much quieter but not quietist way, his story bespeaks a rebuilding of personal world, a form of autopoetic resilience, where survival is not a passive condition but a process of corporeal emergence, to be continually enacted through everyday embodied practices. These in turn facilitate a transfer of sentimental attachment, an affective shift away from the rationales of both the communist party-state system and the postsocialist neoliberal market, toward a self-valuing ethics and deeper kinship intimacies.

Rather than interpret these living practices cynically, as a naïve buying into the false promises of the good life in an individualist capitalist society, or what Lauren Berlant (2011) would call the slow death of cruel optimism, we might see in Pang a conscious embrace of a nonelitist biopolitics of care, salvaged from the post-crisis space of epidemic illness. If Anna Tsing (2015) glosses “conditions of precarity” as “life without the promise of stability” (2), then a nonexceptionalist ethics and self-organizing biopolitics such as Pang’s testifies to a desire for postprecarity, a faith in the possibility of everyday life’s meaningful continuance, after disease catastrophe, through small acts of recreated stability. Moreover, similar to Ru Yan’s decision to not resume her internet writerly persona at the end of Hu’s novel, Pang’s post-SARS life was marked by his decision to eschew media attention, which was also an act of not relinquishing his right to live beyond his illness on his own terms, of not ceding his epidemic story over to those already endowed with an inordinate share of power in constructing macro pandemic narratives.

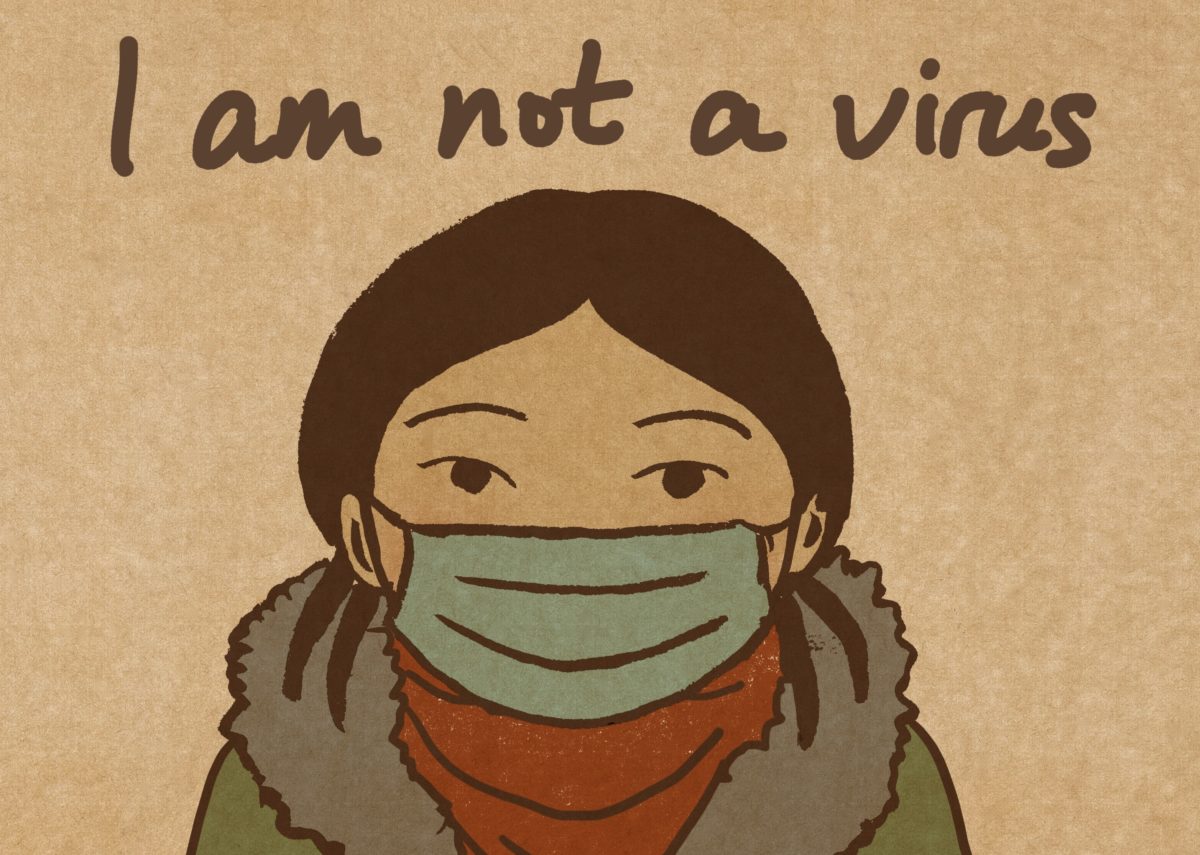

While numerous scholars have analyzed the racist and orientalist dimensions of global media representations of SARS (see Hung 2004; Zhan 2005; Keil and Ali 2008; J. Lee 2014; Lynteris 2018; Lynteris 2020), few have heeded the Chinese index patients themselves, particularly how surviving first patients such as Pang went on to embody new practices and reshape their own living relations to animals and consumption, thus modeling the transition to post-epidemic renewal at disease epicenters. These modifications in bodily conduct toward self and others, both human and nonhuman, deserve attention also as reemergent forms of life. Unlike Michael Fischer’s (2003) notion of “emergent forms of life” at the frontiers of cybernetics and biotechnology, here we observe precisely a retreat from translocal hybrid networks both human-social and human-animal. We observe a foregoing of participation in anthropocentric cultures of species extraction, displacement, and incorporation, and a deliberate return to smaller scales and more proximate relations of life. Even micro decisions and inner commitments—such as a determined letting go of one’s appetite for certain foods, or of one’s involvement in certain toxic networks of mediatized social community—can in themselves represent profound ethical responses to human-nonhuman pandemic assemblages and crises. Withdrawing from one’s neighboring regimes of ingestion and refocusing on the locality of one’s household, leaving be and dwelling alongside the creatures deemed ingestible, releasing the attachment to limitless wealth concentration and historically compensatory pleasure, and carving out the parameters of what one considers actually livable togetherness—these, too, constitute performances of Tsing’s “collaborative survival,” the ordinary and minute navigations of personal “living-space entanglements” (2, 5). In the wake of pandemic ruin, these too instantiate means of recovering life, of rethinking living.

*

Perhaps most of all, I insist on reconstructing Pang’s life because it is startlingly absent in English. So far as I can tell, this narrative arc of Pang’s encounter with and survival of SARS—though fragmented and mediated, and slim by any serious biographer’s yardstick—is missing from the anglophone archive altogether. Of course, anglophone discourse is not homogenous, and I am not suggesting that no writer in English has given an accurate and good-faith rendition of Pang’s story. (In my book’s final chapter, I go into detail about the larger anglophone archive on three SARS index patients, including medical records and epidemiological studies as well as other popular writings both within and outside of China.) One might expect that, as the world index patient, Pang Zuoyao would be a familiar name in the annals of SARS, or in the very least, that the outlines of his experience would have been documented by someone, whether through direct investigation or translation, for an anglophone readership. Yet the exact opposite is true. On a most basic level, Pang’s name has largely vanished from the anglophone public record. This erasure may have come about through a well-intentioned assumption that anonymity protects the patient and his family, though in practice it has only enabled the replication and recirculation of false narratives about him. More insidiously, this erasure feeds contemporary orientalist assumptions about communist China and its totalitarian terror state. One bestselling and critically acclaimed mass market book (Quammen 2012) on animal infections and human pandemics, for example, intimates that “his name goes unmentioned” because of the Chinese government’s censorship of Pang’s story (170-71), when the sinophone sources I draw on are readily available on the Chinese internet. Indeed, in the months during and after SARS, in addition to the dead farmer template, a set of wildly erroneous and deeply orientalist stories emerged about Pang—including fabricated accounts of him as a businessman or salesman (see for example Grady 2003; Rosenthal et al. 2003; Ang 2003; Altman 2003; Abraham 2003; Chao 2003; C. Taylor 2003), a wild animal trader or dealer (see Luck 2003; Bradsher and Altman 2003; Zhan 2005: 37; Jackson 2008: 283), and an exotic game restaurant chef (see Chiu and Galbraith 2004: xv; Seno and Reyes 2004: 7; Goudsmit 2004: 141; Lee and Wing 2006: 135; J. Lee 2014: 18). These stories were told and retold—even by politically committed scholars who set out to critique the racism of SARS discourse—taking hold of the popular anglophone imagination until they bore almost no resemblance to the real Pang, who lived on as if in a parallel universe.

*

Meditating on the possible reasons for the silences around Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s death, Cathy Park Hong (2020) ultimately turns the question on herself:

… But why hadn’t I bothered to find out about her homicide earlier? Didn’t I also type and then delete the word rape before murder when I wrote the review where I mentioned Cha? Rape burns a hole in the article and capsizes any argument. There is no way to continue on with your analysis, no way to make sense past it. You can only look at it or look away—and I looked away. But it’s not just because her death was so grim. I sometimes avoid reading a news story when the victim is Asian because I don’t want to pay attention to the fact that no one else is paying attention. I don’t want to care that no one else cares because I don’t want to be left stranded in my rage. (172-73)

Even more fundamental than the traumatic effect radiating out from Cha’s gruesome death, Hong suggests, is the racialized exhaustion of confronting, yet again, an instance of Asian suffering that goes unheeded, uncared for, the very invisibility or trivialization of which breeds a second-order inattention and indifference. It is not simply the underlying racial anger that one must then manage but the concomitant feeling of certain abandonment, of knowing that one will be “left stranded” in one’s rage by a white majoritarian society that continually challenges and undermines the legitimacy of Asian affect. Following Sianne Ngai’s argument in Ugly Feelings, Hong calls the racialized forms of these affects “minor feelings”: “the racialized range of emotions that are negative, dysphoric, and therefore untelegenic, built from the sediments of everyday racial experience and the irritant of having one’s perception of reality constantly questioned or dismissed” (55). The difficulty of looking at Cha’s killing is compounded by the gendered nature of the crime, and perhaps precisely so, she has come to be conceptually bracketed in yet another way, “as this tragic unknowable subaltern subject” that presumably no one can ethically write about (172). Minor feelings overlaid by poststructuralist schooling can “get in the way of documenting facts” (171).

In confronting the anglophone unwriting/rewriting of Pang Zuoyao, I found myself in a similar affective landscape. Like Hong, I wondered with incredulity and anger: Why hadn’t more writers in the anglophone world tried to spotlight Chinese index patients? Why hadn’t more researchers bothered to reconcile contradictory reports rather than simply echo one or two supposedly authoritative and sometimes obviously questionable accounts? Why didn’t more anglophone researchers and writers look into the medical records and epidemiological studies, some of which are in English and readily available online, or seek out translators for widely accessible Chinese-language sources? And most of all, why didn’t more people care about the actual patients themselves, rather than the big stories and big critiques that their small lives could be instrumentalized to stage? One staggering epiphany I came to was that, the more humanistic the anglophone piece—that is, the more an author explicitly set out to tell a story or analyze stories about SARS or pandemics—the more likely it was to recycle errors and slants, to retell the wrong and often offensive stories about first patients. Scientific studies and medical documents, by contrast, provided a trove of empirical tidbits from which to reconstruct index patients’ disease experiences and social lives.

In a core way, my book’s final chapter has become a reckoning on two levels. The first involves scrutinizing the global power of English as the language of public health knowledge production vis-à-vis pandemic narratives. In keeping with the larger thesis of my book, I believe we can gain positive models for thinking about pandemic experience by recovering, from a largely racist and orientalist archive, the ordinary dimensions of epidemic survival or nonsurvival by Chinese index patients. The second involves probing certain reflexive assumptions and pieties embedded in anglophone humanistic disciplines that are also entangled in the production of knowledge about global public health and global pandemics. In regarding ourselves as important, principled writers and scholars who make macro sociopolitical arguments and broad cultural critiques, perhaps also as savvy poststructuralist critics who are too sophisticated to be burdened by empirical truthseeking, do we end up reinforcing the marginalization of the marginal, the trivialization of the trivialized, and sanctioning the very ideological structures and effects we think we are tearing down?

For the anglophonization of SARS and SARS index cases has been largely a process of humanistic storytelling where real humans disappear, replaced by corpses and zombies. In belatedly arriving at these gaps and distortions, did I too look away, not only out of misguided faith but because I wanted someone else to pay attention instead, to free myself from the menial task of charting small stories and small lives so I could pursue higher-order intellectual critiques and stake the latest field-changing claims? As I finish writing my book’s final chapter, I am frequently aware of my own minor feelings of racialized dysphoria, disbelief, and fury at the anglophone archive with its silences, oversights, blunders, and disfigurements. And by chapter’s end, I too will be left wondering: Would I become isolated in these emotions, invalidated away by a language and a set of writings that have demonstrated over and over again their inattention and negligence toward Chinese subjects? Would writing that emerges from these emotions succeed in overcoming the affective fissures and engender care rather than alienation or defensiveness? However imperfect, this is an attempt to navigate the anglophone terrain amid those affects, and to make more possible alternative stories in which first SARS patients can finally be seen as neither orientalized infrahumans nor tragic unknowable subalterns but just ordinary people. In the time of COVID-19 and beyond, this task, this reorientation, seems more vital than ever.

I want to thank Elina Zhang for soliciting this piece, and for offering a sympatico model of engaged storytelling in her own writing.

Belinda Kong is associate professor of Asian Studies and English at Bowdoin College. Her research focuses on contemporary literature by Asian American and Asian diasporic writers, with focus on the Chinese diaspora. She is the author of Tiananmen Fictions Outside the Square: The Chinese Literary Diaspora and the Politics of Global Culture (Temple University Press 2012, Asian American History and Culture Series), and her work has appeared in Prism: Theory and Modern Chinese Literature, Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, Journal of Transnational American Studies, Modern Fiction Studies, Ariel, and Journal of Narrative Theory. Her current book project, What Lived Through SARS: Chronicles of Pandemic Resilience, explores cultural expressions of epidemic life at the epicenters of the 2003 SARS outbreak.

References

Abraham, Carolyn. 2003. “Decoding of SARS Virus Reveals Animal Origins.” Globe and Mail, April 14.

Adams, Patrick, and Fiona Fleck. 2015. “Bridging the Language Divide in Health.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 93: 365-66. http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.15.02061.

Ali, S. Harris, and Roger Keil. 2006. “Global Cities and the Spread of Infectious Disease: The Case of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in Toronto, Canada.” Urban Studies 43, no. 3: 491-509.

Altman, Lawrence K. 2003. “Virus Called Mostly Under Control.” New York Times, April 12.

Ang, Audra. 2003. “Earliest Known SARS Case Stays Anonymous.” Edwardsville Intelligencer, April 10.

Berlant, Lauren. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Blackwell, Tom. 2003. “All Quiet at SARS Ground Zero.” National Post, June 23.

Bradsher, Keith, and Lawrence K. Altman. 2003. “Strain of SARS Is Found in 3 Animal Species in Asia.” New York Times, May 23.

Bugl, Paul. 2007. “Book Review: SARS in Context: Memory, History, Policy.” Lancet Infectious Diseases 7, no. 11: 710.

Chao, Julie. 2003. “China: Cradle of Mystery Disease.” The Record [Waterloo, Canada], April 21.

Chiu, William, and Veronica Galbraith. 2004. “Calendar of Events.” In At the Epicentre: Hong Kong and the SARS Outbreak, edited by Christine Loh and Civic Exchange, xv-xxvii. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Farquhar, Judith. 2002. Appetites: Food and Sex in Post-Socialist China. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Fischer, Michael M. J. 2003. Emergent Forms of Life and the Anthropological Voice. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Gopalan, Nisha. 2020. “SARS Lessons Inoculate Hong Kong Against Epidemic.” Bloomberg, March 6. www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2020-03-07/coronavirus-sars-lessons-reduce-hong-kong-infection-rate.

Goudsmit, Jaap. 2004. Viral Fitness: The Next SARS and West Nile in the Making. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grady, Denise. 2003. “Fear Reigns as Dangerous Mystery Illness Spreads.” New York Times, April 7.

Hong, Cathy Park. 2020. Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning. New York: One World.

Hu Fayun. 2006. Ruyan@sars.come. Beijing: Zhongguo guoji guangbo chubanshe.

Hu Nianfei, and Ma Xiaoliu. 2006. “Tanfang woguo shouli SARS huanzhe: bingdu laiyuan zhijin reng shi mituan” [“Visiting our country’s first SARS patient: the virus’s origin remains elusive”]. Nanfang zhoumo [Southern Weekend], January 12. http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2006-01-12/10388845907.shtml.

Hu, Xiao-Bing, et al. 2016. “Risk and Safety of Complex Network Systems.” Mathematical Problems in Engineering. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/898391.

Hung, Ho-fun. 2004. “The Politics of SARS: Containing the Perils of Globalization by More Globalization.” Asian Perspective 28, no. 1: 19-44.

Jackson, Paul. 2008. “Fleshy Traffic, Feverish Borders: Blood, Birds, and Civet Cats in Cities Brimming with Intimate Commodities.” In Networked Disease: Emerging Infections in the Global City, edited by S. Harris Ali and Roger Keil, 281-96. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Kao, Raymond W. Y. 2010. Sustainable Economy: Corporate, Social and Environmental Responsibility. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing.

Keil, Roger, and S. Harris Ali. 2008. “‘Racism is a Weapon of Mass Destruction’: SARS and the Social Fabric of Urban Multiculturalism.” In Networked Disease: Emerging Infections in the Global City, edited by S. Harris Ali and Roger Keil, 152-66. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Khan, Ali S., and William Patrick. 2016. The Next Pandemic: On the Front Lines Against Humankind’s Gravest Dangers. New York: PublicAffairs.

Kong, Belinda. 2018. “Totalitarian Ordinariness: The Chinese Epidemic Novel as World Literature.” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 30, no. 1: 136-62.

Lee, Dominic T. S., and Yun Kwok Wing. 2006. “Psychological Responses to SARS in Hong Kong—Report from the Front Line.” In SARS in China: Prelude to Pandemic?, edited by Arthur Kleinman and James L. Watson, 133-47. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Lee, Jon D. 2014. An Epidemic of Rumors: How Stories Shape Our Perceptions of Disease. Boulder, CO: Utah State University Press.

Lee, Paul J., and Leonard R. Krilov. 2005. “When Animal Viruses Attack: SARS and Avian Influenza.” Pediatric Annals 34, no. 1: 42-52.

Leu Siew Ying. 2003a. “On the Trail of SARS’ Ground Zero Patient.” South China Morning Post, April 30.

—. 2003b. “One Year On, the Spectre of SARS Has Returned.” South China Morning Post, November 14.

Luck, Adam. 2003. “Hell that Is the Source of SARS.” Mail on Sunday (London), May 4.

Lynteris, Christos. 2020. Human Extinction and the Pandemic Imaginary. New York: Routledge.

—. 2018. “Yellow Peril Epidemics: The Political Ontology of Degeneration and Emergence.” In Yellow Perils: China Narratives in the Contemporary World, edited by Franck Billé and Sören Urbansky, 35-59. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Ma, Joanne. 2020. “Coronavirus Outbreak: Why SARS Still Leaves a Scar on Hong Kong.” Young Post (a unit of South China Morning Post), February 5.

Marsa, Linda. 2013. Fevered: Why a Hotter Planet Will Hurt Our Health—and How We Can Save Ourselves. New York: Rodale.

Martin, Nik. 2020. “SARS Remembered—How a Deadly Respiratory Virus Hit Asian Economies.” DW.com, January 22. www.dw.com/en/sars-remembered-how-a-deadly-respiratory-virus-hit-asian-economies/a-52088462.

Moura, Nelson. 2020. “Remembering How Macau Avoided the Worst of SARS.” Macau Business, January 22. www.macaubusiness.com/remembering-how-macau-avoided-the-worst-of-sars/.

Nelson, Alex. 2020. “When Was the SARS Outbreak? How the SARS Virus Compared to Coronavirus—and Whether It Reached the UK.” Edinburgh News, March 11.

Ni, Ching-Ching. 2003. “Tracing the Path of SARS: A Tale of Deadly Infection.” Los Angeles Times, April 22.

Penuel, K. Bradley, Matt Statler, and Ryan Hagen, eds. 2013. Encyclopedia of Crisis Management. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Quammen, David. 2012. Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic. New York: W. W. Norton.

Rosenthal, Elisabeth, et al. 2003. “SARS: From China’s Secret to a Worldwide Alarm.” International Herald Tribune [Paris], April 8.

Seno, Alexandra A., and Alejandro Reyes. 2004. “Unmasking SARS: Voices from the Epicentre.” In At the Epicentre: Hong Kong and the SARS Outbreak, edited by Christine Loh and Civic Exchange, 1-15. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Stanley, Ben. 2020. “The First Big Wave: Looking Back at the 2002-2004 SARS Outbreak, and the Lessons We Learnt Ahead of COVID-19.” OnlineMedEd, April 30. https://blog.onlinemeded.org/the-first-big-wave-looking-back-at-the-2002-2004-sars-outbreak-and-the-lessons-we-learnt-ahead-of-covid-19/.

Taylor, Chris. 2003. “The Chinese Plague.” Sunday Age [Melbourne, Australia], May 4.

Taylor, Milton W. 2014. Viruses and Man: A History of Interactions. New York: Springer.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruin. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Wang, May. 2018. “After SARS: China’s Search for Better Health Care.” Harvard Political Review, December 6.

Wikipedia. 2020a. “2002-2004 SARS Outbreak.” Last modified August 17, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2002%E2%80%932004_SARS_outbreak.

—. 2020b. “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome.” Last modified August 19, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Severe_acute_respiratory_syndrome.

WordPress. 2013. “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).” August 20. https://sarsdisease.wordpress.com.

Wu Xia, and Li Nannan. 2013. “Bu xiang bei ren ji zhe de feidian ‘shouli’” [“The SARS ‘index case’ who doesn’t want to be remembered”]. Xinxi shibao [Information Times], January 31. www.360doc.com/content/13/0201/03/200041_263516716.shtml.

Xu, Rui-Heng, et al. 2004. “Epidemiologic Clues to SARS Origin in China.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 10, no. 6: 1030-37.

Yang Lin. 2012. “Feidian shi nian: shouli bingren Pang Zuoyao” [“SARS ten years later: index patient Pang Zuoyao”]. Boke tianzia [Blog World], November 15. http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_5f0b84100102e6eo.html.

Zhan, Mei. 2005. “Civet Cats, Fried Grasshoppers, and David Beckham’s Pajamas: Unruly Bodies after SARS.” American Anthropologist 107, no. 1: 31-42.

Zheng Xiaoling, Wang Changchun, and Chen Gang. 2003. “Foshan Bitang xiang: qijin faxian de Guangdong diyili de yixue diaocha” [“Foshan Bitang village: a medical investigation into Guangdong’s first known case”]. 21 shiji jingji baodao [21st Century Business Herald], May 18. http://finance.sina.com.cn/x/20030518/1555341755.shtml.

Zhou Lixin, et al. 2003. “Guangdong sheng Foshan shi yanzhong jixing huxi zonghezheng shouli baogao” [“The first case of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Foshan”]. Zhonghua jiehe he huxi zazhi [Chinese Journal of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases] 26, no. 10: 598-601.

Zimmer, Carl. 2015. A Planet of Viruses, 2nd edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Zolli, Andrew. 2012. “Learning from SARS.” AndrewZolli.com (blog), July 12. http://andrewzolli.com/learning-from-sars/.