by Sarah Hayden

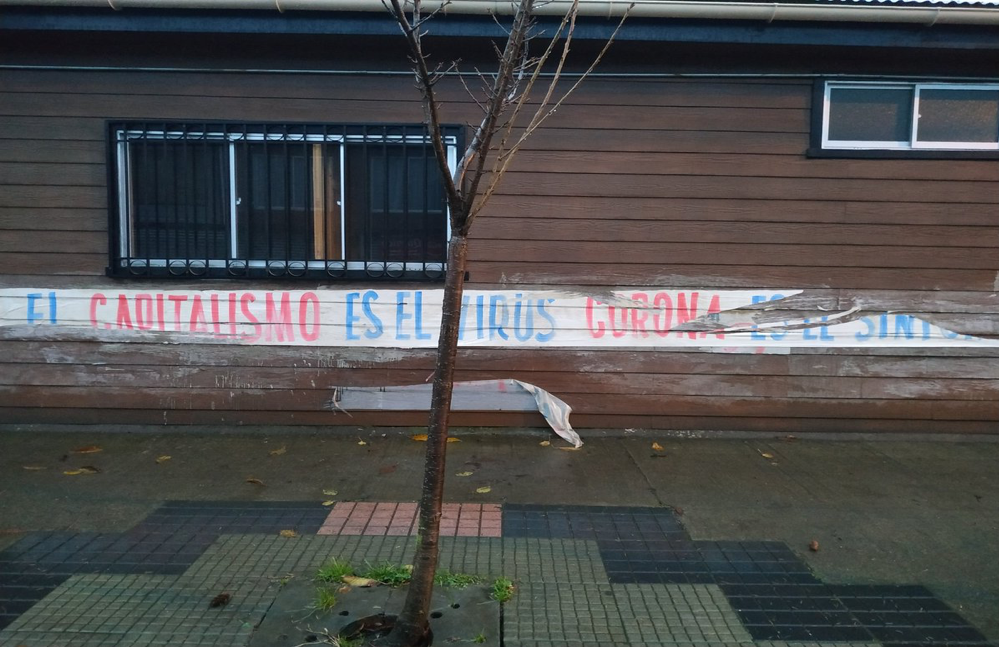

First, galleries became accustomed to being places of sound, and then they became places full of the sound of voices. In the process, the traditional documentary “Voice of God” voice-over has species-hopped into the artworld. Much has been written about the acousmatic voice (a voice that one hears without seeing what causes it) and the power-relations it instates. We know that since at least about 500BC, the “underdetermination of the sonic source” in acousmatic listening has been understood to produce, in Brian Kane’s terms “auditory access to transcendental spheres […] a way of listening to essence, truth, profundity, ineffability or interiority” (Kane 2014: 9). In this essay I want to consider how the voiceover is used to usurp sensorial sovereignty in a single voice-driven art project that imagines, packages and promotes a distinctly 21st-century model of sovereignty. I’m going to take as my case study Christopher Kulendran Thomas’ New Eelam project: a cloud-based housing subscription service promising a “more liquid form of citizenship beyond borders; citizenship by choice” (Kulendran Thomas 2017a: 108).[1] As advertising-as-art, it sells a dream of neoliberal sovereignty: a near-future in which “likeminded people” form cloud communities in unbounded geodesic space. However, the new economic model sustaining this hazy utopia is predicated upon a curiously homogenous (though mobile and globally distributed) demographic, and while it denounces the coup that precipitated the dissolution of the neo-Marxist autonomous state of Eelam and the annihilation of Sri Lanka’s Tamil minority, the project positions itself as irrecuperably post-political. A 2017 press release for the project states that the “authoritarian Sri Lankan president” carried out this act of genocide while “protected by a cloak of national sovereignty” (Kulendran Thomas 2017b). In its stead, Kulendran Thomas proposes a kind of deterritorialized hipster sovereignty premised on frictionless mobility and liquid citizenship.

New Eelam is a largescale multimedia project which, since 2016, has developed to comprise a website, “experience suites” (life-size models of domestic interiors, differently configured for each setting), and moving image works of various types which articulate and illustrate the concept. Individual iterations also incorporate a selection of prints, backlit tension fabrics, ceramics, furniture and sculptural works commissioned from other artists, as well as hydroponic planting systems, and assemblages drawn from Kulendran Thomas’s prior series, When Platitudes Become Form. Crucially, all of these components contrive to construct an elaborate (if distinctly minimalist) setting in which New Eelam promotional films and videos play and from which the New Eelam website can (e.g. via iPad) be easily accessed: a wrap-round, cross-media advertising “experience.”[2]

However, notwithstanding the complex and multifarious nature of this project-in-process, it is the voiceover and its non-sounding graphic ghost that do all of the work in New Eelam. The text we encounter either as evanescent voice or equally evanescent captions is what animates and gives purpose to all the rest of what would otherwise sum to no more than an unfolding series of unusually corporate-luxe IKEA show interiors. The films and videos—the former of which are composited from masses of found and (what looks like) stock footage, the latter of which can boast little more by way of an imagetrack than indifferently slick animations—derive all meaningful (if dubious) content from the project’s seductively voiced (if not always audible) self-description. My analysis will treat two components of the New Eelam project: the audible voiceover of the “speculative documentary” film, 60 Million Americans Can’t Be Wrong, and the inaudible nonvoice of the readable captions in the micro-video series, NE_MV_01-08. What I’m going to argue is that New Eelam’s fantasy of sovereignty is channelled through the project’s undermining of sensorial sovereignty—via voices heard and unheard.

Liquid Citizenship and Nebulous Sovereignty

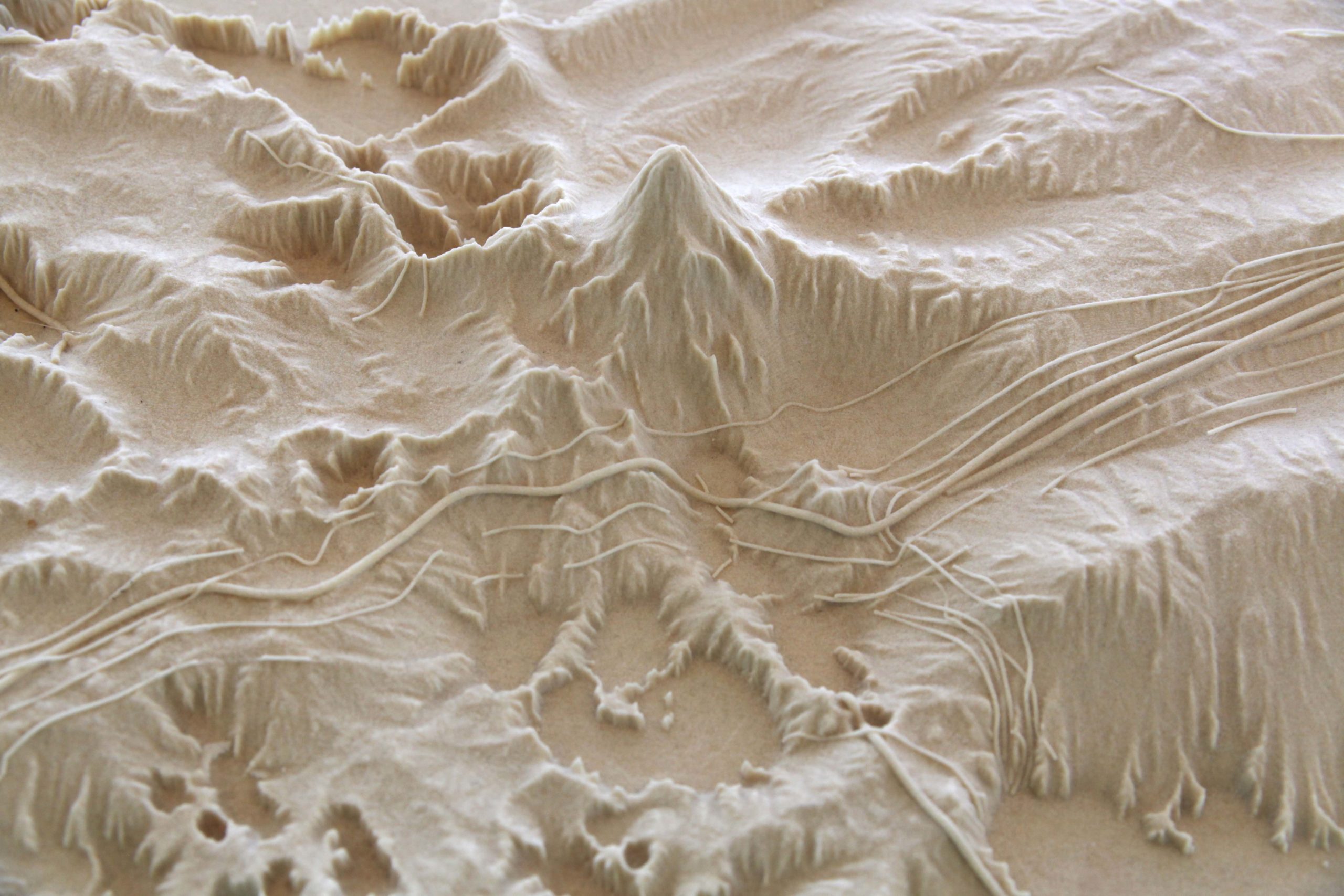

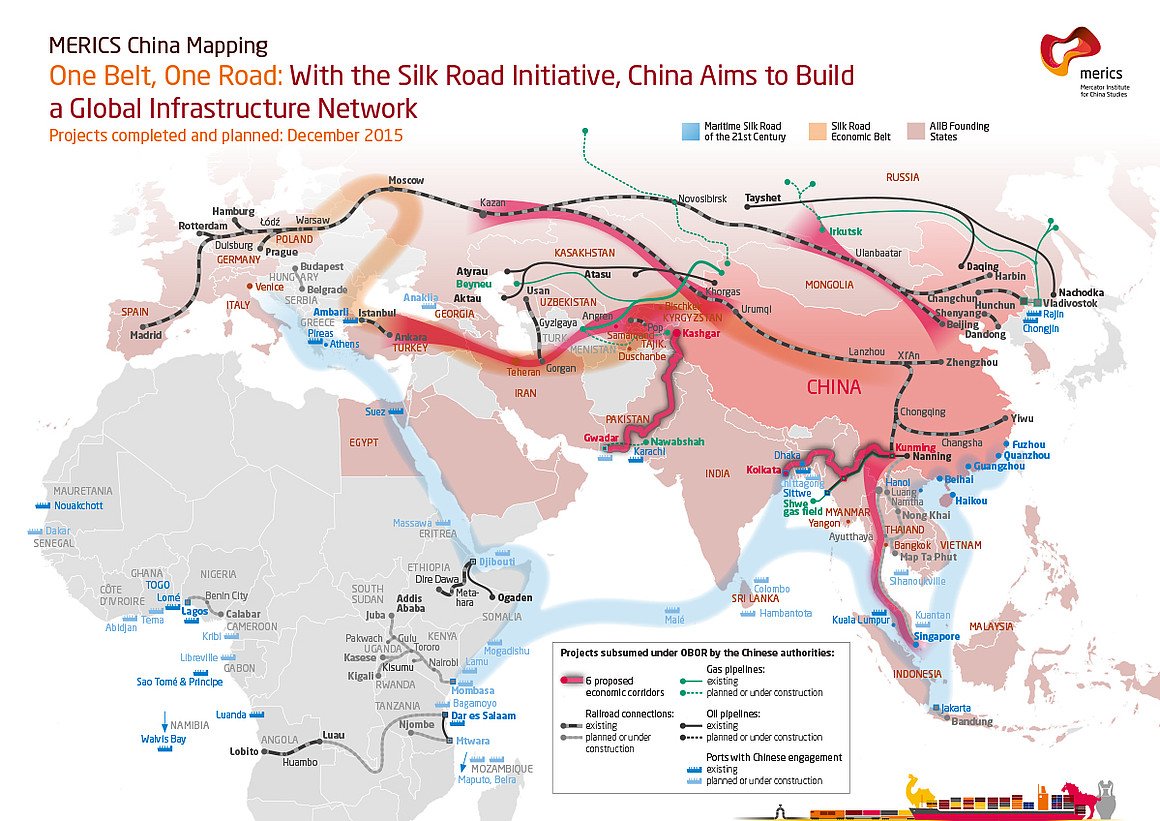

In 2009 in the wake of the destruction of Eelam, Sri Lankan President, Mahinda Rajapaska, announced: “We are a government who defeated terrorism at a time when others told us that it was not possible. The writ of the state now runs across every inch of our territory” (Parasam 2012: 903). The image Rajapaska invokes is of cartographically conceived space: what Eyal Weizman calls a “planar division of a territory” (Weizman 2002). In order to identify a site beyond this and every other “writ of […] state,” in his construction of New Eelam, Kulendran Thomas goes beyond Weizman’s verticality, Virilio’s oblique tri-dimensionality and Elden’s volumetric encompassing of “the earth; the air and the subsoil” (Elden 2013: 15). The territory of New Eelam is shaped by Supra-Euclidean dimensionality: the cloud is twice figured as “an entirely new dimension”, Google is saluted for its bravery in “operating in a completely different dimension”, and a reinvented Microsoft is recognized for having followed them into it (Kulendran Thomas 2017a: 102-107). Geographically dispersed, New Eelam understands its jurisdiction as, instead, generated by the “densely interconnected network” of like-minded individuals sharing “states of mind” in geodesic space (Kulendran Thomas 2019: 5). As to how this inter-psychic space relates to the more prosaic network of communally owned apartments all over the world’s most hipster-gentrified cities, this is less than fully articulated.

The terrain of New Eelam is conceived as in flux, “continually reshaping”, in process, in terra(less) formation within the cloud: “a distributed network rather than a territorially bounded nation” (Kulendran Thomas 2017a: 108-109). This makes it possible for the citizenship it offers to “transcend geography”, flowing beyond, past and through national boundaries in a victory of the politics of the vector over the politics of the envelope (2017a: 97; Wark 2004: 246). The exact process by which this is intended to occur remains nebulous. We hear that the locational lottery determining the “hereditary privilege” of nationality is to be replaced with a system of “citizenship by choice”: but how? In its initial form, New Eelam will be constituted immaterially, “with its idea liberated from its land” (Kulendran Thomas 2017a: 109). However, eventual condensation of this vaporous entity is imagined, with a moment anticipated when New Eelam’s “cloud formations could take physical shape at greater and greater scales and dimensions” (Kulendran Thomas 2017a: 114). Should examples be required, Tinder, Pokémon Go, Anonymous and the Arab Spring are offered as templates for how “cloud towns, cloud cities, and even cloud countries [could] materialise out of thin air” (Kulendran Thomas 2019: NE_MV_06). As is evidenced by so many of the most perniciously fraught conflicts of recent decades, virgin territories can not usually be called into being on the basis of the whims, wishes or even most the urgent needs of would-be autonomous peoples. Perhaps the Vatican can provide a template: a deterritorialized sovereignty, summoned into being by the intersection of financial might and faith.

While it’s easy to envision a group of tech-utopians declaring their independence and so effecting a form of internal sovereignty, it’s quite a lot harder to imagine how or why any exchange of recognitions might be imagined between New Eelam and any of the incumbent powers from the “old World of Nations” out of which prospective New Eelamites are called to emigrate (Kulendran Thomas 2017a: 114). External sovereignty in the real world might prove as elusive as does elucidation. Extant power-relations between states and the technology companies whose tax bills they are so keen to waive make it possible to imagine a near future in which certain governments would nominally approve some form of novelty dual citizenship so that tech scions could swear part-allegiance to the cloud. It’s harder to envision the same governments ever handing over the land that would be required to host the population in its eventual physical incarnation—particularly if, as the closing statement to the film makes clear, the mission here is not one of “opposing incumbent systems by force” (Kulendran Thomas 2017a: 113). In this, as in much else, New Eelam’s future is already upon us. In The Stack, Benjamin Bratton poses the First Sino-Google War of 2009 as exemplary of “a geopolitical conflict between empires”: one that “pits a state that would dominate and determine the network sovereignty of information and energy flows versus a platform that would, by assembling users into another real network and imagined community, exceed, in deed if not letter, the last-instance sovereignty of the state and determine an alternate polity in its own image” (Bratton 2015: 112). The New Eelam project is a durational exercise in fantasizing about how such an alternate polity might function.

At the beginning of 60 Million Americans, the artist’s voiceover invites us to hark back to a halcyon “long ago” when “there was nothing more natural for the human species to explore new territories” (Kulendran Thomas 2017a: 97). Yet, even as “Our ancestors moved throughout the land, discovering new horizons and sharing what they had with each other” (Kulendran Thomas 2017a: 97), they also engaged in various more violently intrusively acts against those they encountered in the course of these bucolic adventures. Although there is no promise of violence, threats of mass exit abound: NE_MV_08 asks whether “every country will become a software country or risk losing its citizens” and NE_MV_07 asks “what will happen to nation states when everyone has the power to leave.” One wonders where, exactly, all of these exiles-elect will go.

Key to the legend of New Eelam is the framing of Google’s core business plan—“[making] its applications freely available in return for its users data and attention”—as “a new kind of social contract” (Kulendran Thomas 2017a: 105). However, notwithstanding the associations summoned by this term, it’s hard to equate the terms of the compact based “on the conveniences that could be provided by targeting the messaging that would be most interesting to each individual user at the place and time that it would be most relevant to them” (Kulendran Thomas 2017a: 105), with those conferred upon the contracting partners of, say, Hobbes or Rousseau. 60 Million Americans compares 21st century democracy to the “crumbling monarchies” of 16/17th-century Europe. But the only example offered for how this new cloud-state might operate comes by way of a reference to an experiment by the art collective, the Mycological Twist, who attempted to subvert the embedded social infrastructure of the survivalist videogame, Rust, by playing collaboratively rather than (as the game designers apparently expected) purely for individual gain. Gameplay, then, and a techno-utopian “design challenge […] to make the iPhone or Tesla of housing” (Bucknell 2019). We are apprised of no gameplan for how this new cloud-state will constitute or legislate itself beyond, perhaps, something akin to the flimsy agreements existing between users and providers on the likes of: Air BnB, Uber, Facebook etc.—a taking on faith that anyone sufficiently rightminded to subscribe or “partner” can be relied upon to behave ethically, civically or decently. But of course, as we’re already seeing, and as New Eelam surreptitiously acknowledges, it is very hard to prosecute misdemeanours committed by vaporously non-located global actants whose behavior is guaranteed only by the optimism of a bro-to-bro promise not to be evil.

The basis for New Eelam’s claims to the legitimacy of its sovereignty appears to derive in large part from the sheer size and might of the “really big companies” (Kulendran Thomas 2019: 03) it anticipates: the companies that, together, form a new ruling class whose “class power derives from ownership and control of the vector of information” (Wark 2019: 13). This is what McKenzie Wark has termed the “vectoralist class” (Wark 2019: 11). When one micro-video closes with the question—“so how will the biggest organizations of the future be governed?” (Kulendran Thomas 2019: 02)—we are cued to read it as rhetorical: the implication being that such “massively scalable organizations that are funded and built by the communities” (Kulendran Thomas 2019: 04) and enabled by blockchain technologies will simply be too big to govern. They will generate aporia that only they themselves can fill. As Bratton observes of Google, such platforms are both too big and too small for states to control (2015: 112). Immunity to subordination is guaranteed by their immunity from apprehension and, accordingly, accountability. In NE_MV_02, Vitalik Buterin’s Ethereum “community” is offered as an example of “more loosely defined ecosystem” of “fuzzy sets” that states “can’t target […] as easily as conventional companies”. The New Eelam line is that trust in these organizations will be generated by the confluence of anonymity, decentralization, ubiquity, collective ownership that derives from the fact that “in today’s informational economy where value is created through data, we are simultaneously the workers and the product that is sold to advertisers” (Kulendran Thomas 2019: 01). Or, in Wark’s terms, we are made subject to the vectoralist imperative “to be able to extract value not just from labor but from what Tiziana Terranova calls free labor” (2019: 115). New Eelam proposes that hugely powerful “decentralized autonomous organizations” will “command a deeper degree of trust than today’s big businesses because they will be owned and governed collectively by their users” (Kulendran Thomas 2019: 04). The promise it makes is that the intermediaries and intercessors of representative democracy will be rendered redundant by corporately-choreographed direct rule, but the nature of that rule remains up for grabs. The fact that the cryptologically blockchained programmable tokens in which these companies are held means they “can be owned by anyone” (Kulendran Thomas 2019: 04), also means they are open to manipulation by invisible forces other than the well-meaning, forward-thinking young professionals presumed to make up its putatively cooperative usership.

New Eelam spins itself as a collective united in “citizenship beyond national borders” and, in so doing, appears to hold out the promise of a whole new way for its subscribers to “feel part of something”. Its techno-optimist rhetoric is woolly with talk of cooperatives, belonging and Zuckerbergian “community”. But the more we prod at what is being promoted, the more it discloses itself as a means to be, instead, apart: not just from nationality, but (much more significantly) from society. Founded on the pursuit of self-actualization and unbounded autonomy this dream of corporate cooperative sovereignty is destined to develop as, instead, a metastasized nightmare of neoliberal hipster sovereignty of the individual. No legislation would protect against mega-corporations requiring an opt-in citizenship that ensures their membership will be formed of those least likely to need the kind of supports nation-states once guaranteed to the young, the sick, the old, the infirm. No rationale is offered for how or why these fuzzy corporate masses would ever make any decisions not immediately seen to be in their own interests. No explanation is provided for how this new “collective being” will deal with what Rousseau referred to as the “physical inequality as nature may have set up between men” (2003: 199-200) or, indeed, for the fluxing capacities of those physical beings across their lifetimes. No attempt is made to imply that there will be “no distinctions [drawn] between those of whom it is made up” (Rousseau 2003: 207). Nor is any plan made for when intrigues or factions arise, and “partial associations are formed at the expense of the great association”: inevitabilities of human interaction that were foreseeable in 1762 and remain grimly probable today (Rousseau 2003: 203). Instead, New Eelam seems to share with Facebook an intransigent faith in the moral rectitude of the mass, and its self-regulating destiny. In joining the cloud community, the New Eelamite undertakes no Rousseauian exchange, but only carries out a transaction. In subscribing to the scheme, no natural independence or strength must be offered up in exchange for the benefits to be conferred. Under the “luxury of communalism” that provides the infrastructure for a New Eelam life of constant globetrotting, there is no suggestion that one’s own property must be forfeited. Even bearing in mind half-hearted predictions about an eventual trickle-down effect, it’s a curious kind of communalism in which the powerful stand to retain their inherited advantages while paying to attain some new ones. At the end of 60 Million Americans, the voiceover asks: “if the way that housing works could be transformed through a new industrial revolution, what new social forms might this open up?” The likelihood is that instead of transforming social structures, this “new offshore economic system” will only accelerate and render more acute the extant situation (Kulendran Thomas 2019a: 111). As Wark puts it, however slow we have been to recognize this, “It is not the ideologies of humans that determines their social-technical existence, but their social-technical existence that determines their ideologies” (Wark 2019: 36). While New Eelam itself was only incorporated in 2016 and hasn’t (yet) taken over the world, the appeal of its fiction of techno-logically enabled autonomy is already familiar, already shaping everything about the delivery and practice of education, employment, social care.

This vision of sovereignty resonates curiously with that espoused in the more openly hard-right libertarian book of prophesy, The Sovereign Individual (1997), by James Dale Davidson and William Rees-Mogg. Marketed as a handbook to the near future, The Sovereign Individual anticipates the advent of the “genuine privatization of sovereignty” (Davidson & Rees-Mogg 1997: 321), made possible by the destruction of the nation state by “microprocessing” and a resultant “eclipse of politics” (Davidson & Rees-Mogg 1997: 15). Like Kulendran Thomas, they cite Alfred O. Hirschman as antecedent. And like him, they offer a vision of liquid movement (for some) in which “Ultimately, persons of substance will be able to travel without documents at all” (Davidson & Rees-Mogg 1997: 321) and massive cyber corporations will enjoy a revolutionary “transcendence of frontiers and territories” that puts them beyond government (Davidson & Rees-Mogg 1997: 23). In keeping with their respective times, Kulendran Thomas artfully avoids acknowledging the vast inequalities that his system will support, but Davidson and Rees-Mogg are unabashed in admitting—or, rather, celebrating—the fact that “this will be increasingly a ‘winners take all’ world” (Davidson & Rees-Mogg 1997: 300). They write of how “the Information Revolution will liberate individuals as never before”, leaving individuals “almost entirely free to invent their own work and realize the full benefits of their own productivity” (Davidson & Rees-Mogg 1997: 17-18), under a new employment system compared (amusingly) to opera. Not everyone can be the prima donna. So, while “[g]enius will be unleashed” (Davidson & Rees-Mogg 1997: 18), “the return for ordinary performance is bound to fall” (Davidson & Rees-Mogg 1997: 300). Even Davidson and Rees-Mogg’s (1997: 28) direly dystopian late-twentieth-century vision of a world in which “denationalized citizens will no longer be citizens as we know them, but customers”, couldn’t quite predict how the workers of the neoliberal 21st century would come to be deprived of not alone their wages but also contract-guaranteed hours, workplaces, and the scantest security. Their forecasts of how HNW individuals “will no longer be obliged to live in a high-tax jurisdiction in order to earn high income” as “governments that attempt to charge too much as the price of domicile will merely drive away their best customers” (Davidson & Rees-Mogg 1997: 21) read like the withheld corporate documents, the secret memos that underpin and explain the nature of the New Eelam mission: for it is this—exemption from tax—that is surely being signalled but never explicitly advertised as one of the perks of New Eelamite liquid citizenship. The packaging is different but the core content here is strikingly similar. New Eelam sells an updated, redesigned version of individual sovereignty, cloaked by the more palatable, millennial-marketable apparel of the autophagic “sharing economy.”

New Eelam promises that, as a consequence of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, unfettered individuals freed by technology of the burdens of any form of social bond or responsibility will come to flow through the world unconstrained by borders, laws, taxes, or society itself. Beyond the established California Ideology of technology as “good in essence” (Wark 2019: 73), the transcendence of time and space is frequently celebrated as a victory for technology in terms that often carries curiously super-human/divine associations. Rees-Mogg and Davidson wrote of how the “most successful and ambitious […] truly Sovereign Individuals” would “compete and interact on terms that echo the relations among the gods in Greek myth”, carrying through this disturbing analogy to describe how, upon a cyberspace “Mount Olympus”, these divine beings will escape politics, transform the nature of governments, “[shrink] the realm of compulsion” (which we might otherwise term responsibility, and “[widen] the scope of private control over resources” (Davidson & Rees-Mogg 1997: 18-19). This celestial note will re-sound, when I come to discuss the mutation of the documentary Voice of God within the evolution of the New Eelam project.

Exit, Voice and Loyalty

The intentional community invoked by New Eelam is one of “entire cloud countries” based on “citizenship by choice rather than by hereditary privilege.” In 60 Million Americans Can’t Be Wrong, the voiceover energetically sets about legitimizing the viability of the choice to opt out of a society you deem to have gone astray: the replacement of democratic rule with consumer choice. It cites Albert O. Hirschman as evangelist of mass exit as solution and describes his 1970 book, Exit, Voice and Loyalty, as “quietly influential” among Silicon Valley Techno-libertarians. We hear that Hirschman: “looks at how customers, members of citizens tend to exercise their democratic voice—for example through complaints, suggestions, votes or protests—only when they believe an organization is open to change; whereas, if they realise that the system can’t be changed from within, they leave” (Kulendran Thomas 2017a: 101). However, as noted above, citizens of a nation state cannot usually simply turn up in a new country, revoke their prior citizenship and adopt a new one. In fact, Hirschman even admits this kink in his model, when he writes of how the exit option is very nearly unavailable “in such basic social organizations as the family, the state, or the church” (and, in economic terms, in “pure monopoly”) (Hirschman 1970: 33).

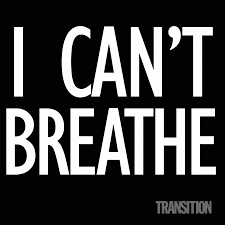

Later in the book, Hirschman admits of the friction produced when non-liquid citizens leave one country for another: acknowledging that “the emigrant makes a difficult decision and usually pays a high price in severing many strong affective ties” and referring to an additional payment “extracted as [the emigrant] is being initiated into a new environment and adjusting to it” (Hirschman 1970: 113). When New Eelam promises that with cloud citizenship, “the whole world could be home” (Kulendran Thomas 2017a: 114), it also promises the replication, in each global apartment, of an eidetic, neo-international style, Air BnB interior design aesthetic This promise of identical experiences “wherever you need to be” smoothes away the prospect of any adjustment process as “you” transition between cities. It erases that irritating degree of difference once considered the purpose of international travel. What it doesn’t have a design hack for is the more pressing, and ever more present rub of walls, borders, biometric passports, quotas, social insurance numbers and right-to-work visas.[3] 60 Million Americans conspicuously avoids mentioning any such sticky issues. But before the artist’s voice starts to bamboozle us, the film’s unvoiced prologue prefaces what follows with montaged media footage of migrants frantically attempting to cross walls and borders. Similarly, when the voiceover guides us through its condensed lesson on Hirschman’s concept of voice as “any attempt at all to change, rather than to escape from, an objectionable state of affairs”, it does so over montaged footage of tear-gassed riots, protests, Black Lives Matter marches: images featuring a high proportion of people of color. However, when the voiceover speaks of exit, the images we see of people leaving are homogenous and highly freighted: of white people packing up files and folders, walking out of office buildings with boxes—images familiar to us (whether associatively or actually) from the media coverage of the activities of banks in the crash. The bodies that exit are besuited, unmolested (except, perhaps, by paparazzi) and moving independently. These are the people that can leave, walk out unscathed. What Hirschman calls “the neatness of exit” is available only to certain subjects, certain bodies, certain sets of papers. And the film acknowledges that with one channel (onscreen), even as it denies it with another (the voiceover). From the outset, the voice is established as manipulative, dogmatic, stage-manager. We have been warned.

For Hirschman, voice equates to “any attempt at all to change, rather than to escape from, an objectionable state of affairs” (Hirschman 1970: 30). While voice operates here in its habitual metaphorical mode—as a figure for the expression of political feeling, as the “use” of one’s political “voice”—it is not entirely abstracted from the voice as sound, its sonorous potential. He writes of how, in an “age of protest”, “dissatisfied consumers (or members of an organization) [….] can ‘kick up a fuss’”, as a means to induce improvement. They might also make “individual or collective petition to the management directly in charge, through appeal to a higher authority with the intention of forcing a change in management, or through various types of actions and protests, including those that are meant to mobilize public opinion” (Hirschman 1970: 30). Perhaps some of what makes it possible for the “exit option” to take on such power is the diminution of the potency of the “voice” that was its counterpart. Where for Hirschman, it was broadly but tangibly conceived, in the rhetoric of 21st century techno-power, voice has become impossibly, untenably elastic. Mark Zuckerberg’s highly contentious October 2019 oration on free speech at the University of Georgetown exemplifies the degree of its attenuation as metaphor. In a speech that argued the necessity of promulgating false political advertising as free speech, the Facebook CEO starts from the presumption that voice equates to having access to his social media platform. This is what makes it possible for him to claim that, as a result of the company’s efforts to connect the world, “a lot more people now have a voice” (Zuckerberg 2019). The broadcasting of one’s views, breakfast or holiday photos all constitute equivalent exercise of that voice; but we are also advised that “Voting is voice”—and, shortly after, that “political ads are an important part of voice”—even when they lie (Zuckerberg 2019). Although the speech makes numerous ill-judged (and justly ill-received) references to Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement, and Zuckerberg makes a point of how the platform is used by activities and protestors, the overall effect is to neutralize voice by conflating actual political expression with the means for self-expression within an algorithmically-artefacted silo in which political reality can be manipulated (for the profit of tech companies) by malign agents to geo-politically significant ends.[4]

Using one’s voice need not be noisy. Mladen Dolar describes the operation of the necessarily scriptoral, and so silenced, electoral voice of the individual voter, marking their anonymous, secret X (Dolar 2006: 111-112). And somewhere, buried deep within even Hirschman’s notion of the vox populi is a remnant of the inner voice as moral arbiter: the inaudible, unignorable “materialisation of conscience” (Riley 2004: 67). This “still small voice” which, as Denise Riley points out, was in its original Biblical manifestation an external divine voice that later came to be conceived as internal, integrated within the moral human psyche (2004: 67). Dolar writes of the “internal voice of a moral injunction, the voice which issues warnings, commands, admonishments, the voice which cannot be silenced if one has acted wrongly”, and tracks it from Socrates through Rousseau, Kant and Heidegger, to conclude that this internal voice is always marked an external at the interior, or the Other within the Self (Dolar 2006: 102). Hirschman’s voice that means “to make an attempt at changing the practices, policies, and outputs of the firm from which one buys or of the organization to which one belongs” (Hirschman 1970: 30), signifies engagement and activity as opposed to withdrawal, and noise as opposed to quietism— trying to improve the situation for the common good, rather than removing oneself. Thus externalized and exercised, vocality comes to sound like morality: an attempt at fixing the problem, rather than leaving it for others to deal with. Abandoning the electoral voice in favor of “the exit option” may mean jettisoning this moral voice, too.

No real attempt is made to suggest that the departure of New Eelam’s newly freed, sovereign liquid citizens is intended to bring about a major change-of-mind or policy in the nation-states they would presume to leave behind. Rather, the New Eelamite skips away, unconcerned for the future of a state they no longer recognize. For Hirschman, the “neatness of exit” is posed against “the messiness and heartbreak of voice” (Hirschman 1970: 107). The curious melding of the physiological and psychological in “heartbreak” illustrates his embodied, moral, engaged concept of “voice”. Making a fuss—protest, activism, complaint—is figured as both more emotionally strenuous and more corporeally invested than the apparently easier, tidier “exit option”. Of course, how one weighs such costs might depend on one’s vantage point. Hirschman takes as one of his examples of exit in action “the progressive settlement of the frontier” in the United States by disgruntled Europeans, and later by Americans moving from East to West (Hirschman 1970: 107). This image resonates with New Eelam’s colonially acquisitive and extensive drive to make it so “the whole world could be home” (Kulendran Thomas 2017a: 114). While Hirschman acknowledges the fact that the settler fantasy of American nationhood “provided everyone with a paradigm of problem-solving” by making it imaginable for Americans “to think about solving their problems through ‘physical flight’”, he extends little thought to the “heartbreak” experienced by the pre-existing populations of this un-empty vast country (Hirschman 1970: 107). However this might have been received in 1970, the seemingly uncritical re-presentation of these ideas in the 21st century should give us pause, particularly when we hear it so flippantly framed in 60 Million Americans: “Where they actually built it wasn’t all that new to the native populations that they displaced. But for those that they had left behind back home, it was a bold experiment, in a different way of life” (Kulendran Thomas 2017a: 100). The ethical implications of the voice-V-exit dilemma acquire an additional charge when the choice is framed as that between “kicking up a fuss” at home and colonial expansion—and consequent population displacement—abroad.

While Hirschman’s vision is predicated on the expectation that migrant exiters would come to be citizen-subjects in their new homes, Kulendran Thomas has no such plan. There is no suggestion that this “new social contract” will entail any new (or, indeed, the maintenance of any vestigial) civic obligations or care responsibilities. The New Eelamites would also, presumably, be freed from the yokes of taxes, national insurance, social responsibility. Thus freed, the New Eelamites would not come together to constitute the geodesically cosy communities so vaguely but insistently implied in the advertising. Instead, in the absence of any other blueprint for a new society, each liquid citizen opts out in order to attain the status of monadic-nomadic: or sovereign citizen of the cloud. In light of the growth and politics of the sovereign citizenship movement in the US, the decision to model New Eelam’s aspirational atomization of society on an arty takeover of a survivalist videogame no longer looks arbitrary or accidental. Having outlined the form of its model sovereignty, I want to move now to consider how New Eelam articulates the dream of sovereignty it espouses, and how that dream is belied by the ways in which it is “voiced”, by the voice used to sell its mass exit strategy.

Liquid Voice

Bodiless, unbounded by the banality of being anchored within a visible mortal, the documentary “Voice of God” attempts to insinuate itself into our thinking as straight truth, spoken from the authorizing position that denies it is a position at all. It speaks as though from on high, from outside of, or on behalf of the text, from everywhere and nowhere at once. When the voice is thus preserved from identification with a single mortal being, as Carolyn Abbate (1989: 69) notes “power accrues to the utterance and not the person; words are also freer, something more than the speech of a human being”. The acousmatic voice is, as Brian Kane (2014: 213) puts it, “the voice of obedience and belief”. We hear this “spirit without a body” (Dolar 2006: 62), ineluctably, as “the voice of the master” (Kane: 213). And as Dolar (2006: 77) observes, the “acousmatic master […] is more of a master than his banal visible versions”. Pooja Rangan (2017: 283) writes of the various moves by which documentary film tried to cast off these troubling pretentions to the divine, the authoritative, expert who speaks for a (presumed or predestined to be) voiceless other. And yet, it seems that these lessons never passed into the artworld, where the Voice of God thunders on, unabated and unabashed, in installations, on speakers and over headphones. In art, as in film, the “voice that hides itself behind a veil” does so, Kane tells us, ‘in order to enjoy the power of omnipotence […] omniscience” and “omnipresence” (Kane: 213, 217). All of these omni-capacities (as various deities would confirm) are very helpful when you want to go about enthralling a public. They sum to a curiously charged arsenal for an artist-author to deploy in a work of art that takes the form of propaganda.

In the context of New Eelam’s status as elaborate advertising platform for a potential lifestyle subscription, Doane’s (1980: 42) assertion that the documentary voiceover “speaks without mediation to the audience, by-passing the ‘characters’ and establishing a complicity between itself and the spectator” is particularly interesting. The tone of the voiceover in 60 Million Americans is pitched to cultivate just such a complicity, cueing its audience (just as advertisers do) with chummy implications of the hearer’s pre-existing inculcation with the attitudes and beliefs that would propel them to subscribe. Its “‘voice on high’ […] which speaks from a position of superior knowledge” (Silverman 1988: 48) seems to address its listeners as at least potential (if not already fully subscribed) acolytes, sure to align themselves with its message, just as soon as they come into possession of this same superior knowledge. As Doane, Silverman and Bonitzer variously remind us, the voiceover’s unlocalizable, disembodied position puts it both outside of time and space and beyond criticism. Acousmaticity stems critique. Without an identifiable speaker to address, it is difficult to produce an adequate rebuttal. This inaccessibility to judgement takes on a new significance in the context of a project that is already resisting interpretation as to its politics, its apparently blank earnestness.

60 Million Americans, the film that constitutes the core of the New Eelam project, is pitched as a “speculative documentary”. A single voiceover voiced by Christopher Kulendran Thomas himself overspeaks its whole, maintaining throughout a vocal style that could be characterized as breezy, bright, public academic. Youthful, anonymous, confidently leading its auditors across yet-unnavigated future, territories, the voice we hear is the sort of voice that explains the indispensability of an app you never knew you needed, and the obsolescence of everything upon which you have heretofore relied. Its solicitous tone—hollow with optimism—is that of the millennial entrepreneur offering not stock, product or service, but “an opportunity” to join the team. It is the voice of the TED-talk That Will Absolutely Blow Your Mind—except, crucially, like the traditional documentary voiceover, it is acousmatic: a voice shorn clear of its speaker. The artist’s vocal performance is smooth, but not machinic. Emphasis is applied where needed, in a manner that is at once subtly expressive (for which: read authentic) and controlled. The recording abjures all of the disfluencies and preparatory sounds that mark oral performances. The mouth’s wetness, the pneumatic system’s breathiness, the muscular exertions of vocalizing, leave no trace on this text. Nor does the artist’s body ever appear onscreen. Indeed, while the credit line for this film includes five separate entries, and cites the contributions of nine individuals, no reference is made to the voiceover or the (presumably laborious) process of its voicing (recording, editing, production)—mindful, perhaps, of Dolar’s warnings (and, before him, those of the Wizard of Oz) as to how discousmatization would cause the banalization of the once “omnipotent, charismatic character”, the crumbling of the voice’s aura, the loss of its fascination and power and (inevitably) “something like castrating effects” (Dolar 2006: 67). This voice is not just disembodied; it denies it ever had anything to do with the “someone in flesh and bone [to borrow Cavarero’s phrase] who emits it” (Cavarero 2005: 4).

The classical disembodied voiceover always arrives to its listener from “a place which is absolutely other. […] Absolutely other and absolutely indeterminable. In this sense, transcendent” (Silverman 1988: 164). Conversely, when the voice in cinema speaks from out of a body, then that body is “anchored in a given space” through the evocation of the voice’s emplaced interaction with its location. All that could “spatialize the voice, […] localize it, give it depth and thus lend to the characters the consistency of the real” (Doane 1980: 36)—reverberation, room tone, sound perspective, etc.—is suppressed in Kulendran Thomas’s voiceover. The recording discloses a contrived paucity of both the “territory sounds” that might root our invisible speaker in an audible environment, and what Chion calls “materializing sound indices”: those markers of the concrete materiality of sound production whose absence we register as purity, ethereality, abstraction (Chion 1994: 114). The quality of sound-recording on 60 Million Americans is clean, almost impossibly so: antiseptic in its eschewal of all diegetic traces of the world beyond the text: no discernible elements of auditory setting. However hard we listen, we learn nothing about the space in which it was recorded. Kaja Silverman (1988: 49) diagnoses the process by which the voice that, in the acousmatic situation, attains transcendence, “loses power and authority with every corporeal encroachment, from a regional accent or idiosyncratic ‘grain’ to definitive localization in the image”. No risk of any such diminution of power and authority threatens this voice without a name, without a point-of-view and without an indexically-invoked “existent in flesh and bone […] a throat, a particular body” (Cavarero 2005: 177). As in a TED- talk, the delivery of information is structured and paced so as to be maximally digestible, maximally intelligible. When information is this easy to come by, the means by which we acquire it are almost impossible to keep in view. This, then, is the liquid voice, that spills smoothly across borders, possessed as it is of no grain, nothing to stick, or be noticed. Voice as very concertedly vanishing mediator. From out of nowhere, the liquid voice flows clear, almost imperceptibly, intangibly, immaterially into the open channels of our ears. It does all it can to effect frictionless transmission. To slip down easy. And to do so, it takes two distinct and yet interdependent forms.

The figure of the ear as the body perceiving organ of least resistance is well rehearsed in the literature on sound and listening. As Brandon Labelle acknowledges, “to give one’s ear […] is to give the body over, for a distribution of agency” (Labelle 2014: x). “The power of the voice [says Dolar] stems from the fact that it is so hard to keep at bay—it hits us from the inside” (Dolar 2006: 78). This anxiety about how what we hear gets inside us, this penetration of the body by the voice of an another, has seeded innumerable metaphors, the most frequently invoked among them being, of course, that of the ear’s tragic lidlessness.[5] Connor sends us back to the derivation of “obedience” from the Latin “audire”, observing that “if a god or tyrant wants to ensure unquestioning obedience, he had better make sure that he never discloses himself to the sight of his people, but manifests himself and his commands through the ear” (Connor 2000: 23). François Bonnet invokes Bernard de Clairvaux’s fantastically circular commentary on a sermon from the Song of Songs, in which the ear is elevated as that which “catches the truth, as truth comes from what is heard, and what is heard comes by the word of God, and the word of God is truth” (Bonnet 2016: 29). There is, presumably, no rightful sensorial sovereignty of the hearer before its God, but when the word of another invades aurally, can we presume to be able to shut it out? Although de Clairvaux constructs his ear in opposition to an easily deceivable eye, to be open to the word of God is also to be susceptible, surely, to other material that co-opts this channel. All of this makes the voice an infamously effective medium for propaganda.

As Dolar observes, “all phenomena of totalitarianism tend to hinge overbearingly on the voice, which in a quid pro quo tends to replace the authority of the letter, or put its validity into question”, supplanting the law (Dolar 2006: 113). Pointing us to Carl Schmitt’s declarations as to the “immediate and most intense” positive law manifested in the Führer’s oral guidelines, Dolar argues that the voice “is structurally in the same position as sovereignty, which means that it can suspend the validity of the law and inaugurate the state of emergency”. It “stands at the point of exception which threatens to become the rule” (Dolar 2006: 118-120). In Dolar’s warnings about how “the moment this voice is taken as something positive and compelling on its own, we enter the realm where obnoxious consequences are quick to follow” (Dolar 2006: 120), we might recognize a strangely doubled inversion of Cavarero’s belief in the power of the relational and specific voice-qua-voice, esteemed even before it says anything. Cavarero’s always already in-convocation political voice does not speak alone, or in a vacuum. It channels its particularity, its Arendtian political potentiality (and, accordingly, its humanity) materially. It is the furthest thing from the appallingly singular, dematerialized Voice of God. For Cavarero, “the speech that is politics explicitly stands in opposition to the universal abstractions of the semantic and its disciplining valence; this speech emphasizes the corporeal roots of the very practice of speaking, along with the embodied existence as she is communicated in speech” (Cavarero 2005: 206). It seems apt, then, that the voice in which Kulendran Thomas’s postpolitical project revives, transmits and reorients Hirschman’s proposition is itself so minimally material and, as the project evolves, ever less sonorous.

While Hitler’s words derived their motive force from the “limitless and unbound” (Dolar 2006: 113) voice-as-missile that always directs us back to the furiously gesticulating, spitting, screaming body on stage, “the Stalinist ruler”, Dolar writes, “endeavors to efface himself and his voice” (Dolar 2006: 118-119). But Dolar then goes on to argue that while the Stalinist weak voice was “a mere appendage to the letter, yet this staging, in order to exhibit the letter as all the more objective, independent of the subjectivity of its executor—this reduction was the source of the Stalinist’s power” (Dolar 2006: 119). It was, he claims, as a result of the very tininess of the self-effacing Stalinist voice that this “hidden appendage” (Dolar 2006: 119) could decide the validity of the letter, which is to say the law. I want to turn now to think about how New Eelam further dematerializes voice beyond acousmaticity to deliver its post-political extirpation of voice as option. In the last part of this essay, I will consider the effect of the friction-defraying suspension of sonority enacted when New Eelam moves from audible voice to ephemerally visible nonvoice.

Mutation: From Voice to Nonvoice

Micro-videos are ultra-short moving image pieces pervasive across social media platforms: popular, appositely, with advertisers and propagandaists alike. As they play, they tend to display short segments of text (a clause, a very short sentence), sequentially, and at a comfortable reading speed. Or, indeed, at the speed of a speaker on a mission to persuade. They do so, crucially, without overtly disrupting the reader-viewer’s experience. Where pop-up advertising interjected loudly into our browsing, these captions permeate an unbroken browsing experience, unobtrusively. Across illimitably scrollable screens, undifferentiated, apparently sourceless evanescent liquid voices speak to us transcendentally, silently, without friction. “Truth” appears: transient, traceless, in flow, in flight, and evaporating even as you read. The micro-video’s suppression of sonorous voice, and its replacement with flowing text, derived from the need for such videos to be embedded within a feed without eroding the goodwill of users by loudly advertising the distracted viewer’s online practices to their workplaces. Text was initially a sort of surreptitious supplement to the voice. Latterly, “content-providers” appear to have jettisoned sound in favour of fleeting text alone.

At New Eelam: Spike Island in 2019, the exhibition formation established in earlier iterations—which typically enshrine a large screen showing 60 Million Americans Can’t Be Wrong at the heart of an experience-suite—was accompanied by the installation, in a sort of vestibular exo-chamber wrapping round the main gallery of eight new works: a series of “micro-videos”, titled NE_MV_01-08 (2019). The exhibition architecture and layout ensure that the viewer will encounter these after having first processed through the temple-like environment of the experience-suite, through which Kulendran Thomas’s voiceover pervades.

The snack-sized works (running from 56-107 seconds in length) that are so displayed assemble a readily digestible case for why the tenor of our times might compel New Eelamites to manifest their sovereign citizenship. Their mission is to characterize the 21st century in terms of a series of exception-al transformations: something like what Klaus Schwab, prophet of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, calls “megatrends” (Schwab 2016). New Eelam supplies eight broadly conceived reasons why normal nation-state citizenship should be suspended. Approaching the eight micro-videos in sequence these are: the fourth industrial revolution; the proliferation of organizations run as fuzzy sets; the claim that distributed ledger technologies are outperforming the profit-generating of targeted advertising; the contention that blockchain technologies enable co-operative corporate ownership and governance; the reorientation of social groupings towards geodesic, rather than geographic networks; the condensation of the cloud—in physical form; a putative new ease of movement; and the global power of software.

The micro-video form was born out of advertising’s desire to better infiltrate and indoctrinate, without generating any friction for the passive scrollers who must not be irritated out of breaking—even momentarily—their connection to the ‘feed’ that drips them billable ads. In 2016, the New York Times reported Mark Zuckerberg’s prophesy of an audio-visual future: “where video is first, with video at the heart of all of our apps and services” (Isaac 2016). Video is where the social and the commercial sides of Facebook’s inextricably entangled “offering” coalesce: preferred medium for “sharing” footage of first steps and promotions on no-sag yoga pants alike. Micro-video is the material Moebius strip of the interaction between the two ends of the Facebook business model, and not without reason. For, as Mike Isaac puts it in the same article, “The more acclimated users are to seeing video content on Facebook, the thinking goes, the less disruptive it will be for people to view video ads alongside them” (Isaac 2016). It is the apparent lack of any discernible edge marking where the “social” stops and the “commercial” begins that gives the functionally split but aesthetically unified micro-video its potently smooth form.

At New Eelam: Bristol, the micro-videos were presented on eight perfectly square (1:1) screens: mimetically recalling the square and vertical video [>1:1] formats that have in recent years colonized the majority of social media channels (including TikTok, Snapchat, Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, Periscope). The vertical/square aspect ratio revolution came about because these formats reduce the need for scrolling viewers to reorient phones or heads in order to take in the whole of the frame. They sand away the rough edges that might otherwise cause friction between infinite units of media content as they rub up against and flow into each other. By minimizing visual snagging, they ensure smooth and uninterrupted “feed” of visually congruent “content” to the user-viewer-customer-data provider (Facebook for Business 2016). In scrolling, the user takes in commercial and social content in an unbroken flow, the space between two blinks. What makes this possible is the presumption of autoplay, which Facebook introduced as “an easier way to watch videos on Facebook” in 2013 (Mayes 2013).

In February 2016, Facebook introduced an auto-captioning tool for advertisers.[6] So when, in May 2018, Google Chrome announced a new Autoplay Policy, enabling autoplay only where “The content is muted, or does include any audio (video only),”[7] advertisers knew what to do. As a result, we have entered a new age of the intertitle—or something very like it. But whereas the intertitles of the early 20th century were interspersed (respectfully) between image frames, in the era of Steyerl’s “poor image” (Steyerl 2009) no one is too worried about overlaying text over disposable image, making this standard practice both for digital marketers and, accordingly, setting the terms for the New Eelam micro-videos. While it would be nice to think the intertitle’s second coming was prompted by a desire to enhance access for Deaf/deaf consumers, captioning increases billable view time and makes it easier to tag videos with searchable SEO metadata. Tracking the conversations about this development, it’s clear that advertisers first panicked about the muting of the voiceovers that had served them so long and so profitably. However, they quickly realised that the transposition of voice into moving text had the capacity to free the content being conveyed from the last, peskily specific, mortal and subjective remnants of grain or materiality that even the acousmatic voice could never quite cast off. The digital marketing blogosphere is abuzz with dramatic claims about increased brand recognition, advert recall, message association,[8] intended to soothe advertisers panicked by reporting on the proportion of these videos that are being watched on mute.[9] Now, columns designed to help advertisers “[Make] Video Ads That Work on Facebook’s Silent Screen” abound.[10] In a strange transfiguring of video’s audio-visual functioning, the burden of information transfer has shifted from the advertising voiceover to the caption stream, and sound has receded to become a nice but nonessential optional extra. This is exactly what we see in NE_MV_01-08: short, captioned, square videos with negligibly significant sound provided on the single-user headphone set that connects to each separate screen.

Sensorial Sovereignty

The music piped into each set of headphones is an unremarkably bland sort of ambient techno: a sonic signalling of nothing more than the era of its manufacture and the technology involved. Its function is much less musical than it is structural. The presence of the headphones produces a viewing regime that is necessarily “singular and solitary” (Young 2016: 10). They lock us into place, and into separate “pods” at each of eight viewing stations, from which we are addressed by the nonvoice of each micro-video. Precisely because gallery audiences have become so accustomed to significant semantic content being delivered via headphones, hearing viewers will almost automatically apply them. They cue us to listen, to tune in, if only to an inner reading voice. Thus installed as reader-viewers, we are clamped by the ear—not in any sonically meaningful way, as we might otherwise have been by a voiceover—but physically: leashed by the short cable running between each screen and its own (though interchangeable) set of headphones. Much as white noise works to screen from distraction, the audio tracks by Dan Bodan and Tony Quiroga block out the sounds of the gallery that might otherwise distract us from attending entirely to what is playing out, in evanescent text, on the screen. A fully smooth and enclosing experience is ensured. Via a mix of real and spectral sensory inputs, the intermittently captive audience is liberated from collective hearing into individual viewing, and made newly permeable to the liquid, legible flow.

Brian Kane (2014: 222) has persuasively demonstrated the overlooking of “technè” in Mladen Dolar’s influential account of the acousmatic. Pettman describes the mutation of the acousmatic voice in the digital age as a two-stage process, comprising first, “the umbilical break from the image” and secondly, the dematerialization of the voice “to a second degree, so that even its medium of capture is no longer graspable […] its portability, its mutability, its absolute liberation from the image, and its saturating ubiquity” (Pettman 2017: 41). I want to suggest that the transition we are witnessing from voice to fluid, fluent text—in New Eelam, as in its advertising context, and more widely—represents the next phase in this process as Cavarero’s (2005: 1) “sonorous materiality” is sloughed off and the voice comes to operate in this still more dematerialized way. The minimally material acousmatic voice is replaced by the fully frictionless immateriality of the textual nonvoice that has no sonic presence and is only ever briefly, partially visible: gone before it can be subjected to scrutiny. In becoming nonvoiced, the micro-video text acquires elements of both Labelle’s (2014: 87-89) unvoice that is inner, preparatory, and Norie Neumark’s (2017: 125) that plays performatively between presence and absence. In the micro-videos, New Eelam’s liquid voice evolves into a liquid nonvoice. In the process, it attains the character of a sort of hyper-acousmatic. I want to propose that the textual nonvoice we’re seeing in the gallery can be identified as a further evolution in a progressive dematerialization of vocality: a second-order mutation along a line that could be mapped from synchronized voice to voiceoff, to voiceover, now to be extended through into the nonvoice’s final, full abstraction as temporally apprehended text.

In documentary, as Pooja Rangan observes, the “voice of god” is attributed “to the body of the film text itself” (2017: 284). In 1980, Mary Ann Doane (Doane 1980: 46) was already warning of the bad faith principles underlying efforts to correct the documentary voiceover’s tendencies towards authority and aggressivity, observing that, by doing away with the central narrator, new documentary formats promoted “the illusion that reality speaks and is not spoken, that the film is not a constructed discourse”. When the overtly authoritative Voice of God cedes to the liquid nonvoice, a similar phenomenon arises. Since the advent of sound in cinema inaugurated the demise of the intertitle as quasi-literary form, writing that appears onscreen has come to be seen (and, increasingly, produced) as an automatic emanation of the film text itself. Whereas intertitles had been recognised as writing, the more recent mainstream cinema has grown used to apprehending all such text as equivalent to the subtitles and closed captions that are broadly considered as purely functional and so, necessarily objective and authorless.[11] As Mark Andrejevic (Andrejevic 2018: 259) describes, the aspiration after framelessness—the fetishizing of “the view from nowhere/everywhere”—epitomizes the logic of big data. Just as the vectoralist megacorps insist on being identified as platforms rather than publishers, so the trachea-circumventing micro-video not only “conceals its own work and posits itself as a voice without a subject” (Doane 1980: 46); it posits itself surreptitiously as a voice without (even) a voice as such, without a position, a perspective, even a source. If the acousmatic voiceover aspires to project the anonymity of its speaker, then the micro-video pretends never to have had a writer at all.

In the replacement of the Voice of God with captions, the extra-intently vanishing mediator that was the acousmatic voice becomes inaudible and doubly vanished, as its each exclamation disappears to be succeeded by the next. The reader never apprehends the whole thing all at once. Instead, morsels of easily digestible writing are meted out at a pace determined by the artist.

The text of NE_MV_07 reads:

You can change your government by voting.

Or you can choose a new government by moving somewhere new.

The world’s wealthiest people already choose where they are legally resident because they can.

And some of the world’s poorest people leave their countries because they have to.

But now moving to somewhere is becoming easier for everyone in the middle too.

So what will happen to nation states when everyone has the power to leave?

The audacity of syllogistic illogic on display here is, in itself, fascinating. Can one really “choose a new government by moving somewhere new”? And in what dimension is “moving somewhere […] becoming easier for everyone in the middle too”? What mythical middle is this, that is not witnessing the dwindling of their roaming rights? That “too” is particularly intriguing. Whereas the third and fourth propositions are initially set up to demonstrate the gap between those that leave “because they can” and those that must “because they have to”, the adverb, “too” retroactively makes of this comparison a litany of like claims. We are left with the astonishing implication that migration is getting easier for everyone: rich, poor and middling, too. This is not the only such sleight of hand. But it is one much more readily accepted—when, as in the case in the installation, the text appears piecemeal across the screen, with the last statement vanishing before the next one takes its place. Chion (irrepressible neologophane) posits the term entrelire, for “glimpsing or seeing briefly or indistinctly” words on the cinema screen: cautioning that the half, brief, or indistinct reading resulting “was not aleatory and fortuitous but a structuring element of the film”, and proposes that we consider such snatched sightings as “Fleeting Impression[s] on First Viewing” (Chion 2017: 125-126). Within the viewing dispositif of the gallery, with the playback controls available to curatorial digits only, writing turns temporal, rather than spatial. In becoming, like the voice, temporally unfolding, the written word approaches what Cavarero (2005: 82) privileges as “the dynamic flux of the vocal”. Putting text in motion enables it to share in Bonnet’s (2016: 7) “irreducible fugacity” of sound. In the case of the New Eelam micro-videos, the rapid replacement of each statement with its successor thwarts any attempts we might make to weigh the syllogistic logic at play. Cognitive dissonance rings out more resoundingly when we are not simultaneously being swept along by a rapidly changing image track and, particularly, when we have the means to stop, slow down, double back across and between pages.

If, as Pettman (2017: 82) argues, voice is really in the ear of the beholder, then my contention is that the inner ear, that is, in Riley’s terms “designed to pick up this voice which owns nothing by way of articulation” (2004: 58), can be the arbiter of its vocality. With the transubstantiation of voice into this scrolling text, the external (though invasive) documentary voice is replaced by an athorybal internal voice that arises in the body of the reader-viewer: the inner voice of the silent reader. There is much, beyond raw grain, that allows us to recognize familiar voices—much as we can recognise the prose style or stylistic “voice” of a particular text. Patterns of flow and pause, lexicon, syntax, punctuation, grammatical idiosyncrasies: all of this conspires, in the micro-video’s streaming text, to produce the impression that we are in the presence of a coherent, if self-effacing, non-sonorous voice. The micro-video dictates to us, its reader-listeners, much as would any canny rhetorician: delivering information in manageable chunks, on a rhythm keyed to maximise auditory comprehension and memory. Punctuated exactly as much as is needed to score (the internal voice’s) non/vocal delivery, it uses italics for emphasis, and question marks in abundance: affectively activating typographical marks that reach towards the reader, making us feel involved, soliciting our continued attention. What the inner ear hears of the inner voice is not pure internality but something inherently infused with and inflected by, what has been taken in from outside (Riley 2004: 73). Because we read the New Eelam nonvoice in the immediate context of the New Eelam voiceover, and because of the non-sonorous features (not to mention the ideologies) they share, we experience our inner voicing of these words as a kind of internal takeover or possession. We read Kulendran Thomas’ words in an internally projected imitation of his voice that we experience as our own. Our inner and his external voices become not just mixed but inseparably intertwined. In encountering his logic, we experience no friction, because the voice speaking is already on the inside. In this sealed in, separated off moment, there can be little more than an infrathin difference between internal and external, self-generated belief and insidiously imposed ideology.

Peter Middleton cites Jesper Svenbro account of how, for the Ancient Greeks, “reading felt invasive to because they imagined that to read was to lend one’s voice and become ‘the instrument necessary for the text to be realized’ (Svenbro 46) in what they sometimes understood as an almost sexual penetration of the self” (Middleton 2005: 83). We can presume that for most modern readers, the experience of silent reading is less threatening of psychic disaggregation. However, this notion of reading as colonization or bodily takeover—an intrusive, even penetrative wresting of the body’s sensorial autonomy—can help to elucidate what happens when, a) as in New Eelam: Spike Island, the athorybal text is presented in an environment that is already awash with the audible acousmatic voice, b) the writing style (aka the “voice”) of the text we read is identical with that of the text we hear, and c) we are shut off from other sensory distractions, rooted in place and set up to pay attention. Escaping earshot of the documentary voice, we experience the shift from hearing to reading as a reclamation of our sensorial autonomy. Wooed by the talk of sharing and community, and becalmed by the aural absence of an authority (or even an author to the text we read) we are primed to imagine that no-one is in charge: to imagine ourselves momentarily sovereign, if only of our private viewing-reading experience. And yet, the artist’s voice can still be heard as a trickle of soundbleed, as we move between the screens installed along this enwrapping corridor, each with their own set of headphones. Catena-like, the distanced tones of his voicebleed thread the listening stations together. As a result, we are freed from the ambit of his sonorous voice only each time we apply the headphones, and turn towards a screen to take in his nonvoice that rehearses—grammatically, syntactically, lexically—the idiolectically and rhythmically distinct character of what we are hearing, what is being carried in the soundbleed from the main exhibition space into the spaces between the works in this surrounding vestibule.[12]

The New Eeelam micro-videos trap us in an unfurling text that pulls us along at the speed and in a rhythm of its own design. As is the case with the audible voiceover, the audience is marshalled to apprehend written text in the manner ordained by an author that refuses to die. In the piecemeal unspooling of the micro-video text, the spatiotemporal axis of regular reading is suspended. Text turns temporal, rather than spatial. In flow rather than fixed. For Bonnet (2016: 211), what makes the ear “the organ of the ‘unproven’; the unverifiable” is because “[w]hat is heard is already no longer there. […] Listening is doomed to form certainties on the basis of evanescent phenomena.” The same applies when what is heard was only ever voiced internally, and heard by the inner ear, in the act of inaudible (though never really silent) phrase-by-phrase reading. Writing on screen necessarily vexes the temporality of the moving image (Chion 2017: 170). But what is certain is that when writing moves across the spatiotemporal axis: from spatial to temporal, from Lessing’s Nebeneinander to Nacheinander, the reader’s critical agency is undermined. Rather than becoming redundant, at the point of the text’s coming into written being, the author of the micro-video persists—hanging around to determine and delimit the conditions under which we engage with its text. The move from encompassing, inescapable voice to mutely ubiquitous nonvoice seems like a shift in direction, but it is in fact a ramping up.

Friction-free

Langdon Winner categorized as “inherently political technologies” those “man-made systems that appear to require or be strongly compatible with particular kinds of political relationships” (Winner 1986: 22). While Pythagoras reportedly installed his magic curtain so that his students could apprehend his words without distraction, the micro-video’s nonvoice is expressly engineered to run in the margins of everything else going on. As one marketer puts it: “Rather than compete for a viewer’s undivided attention, silent video allows your brand to smoothly join in their ongoing media experience. People are much more likely to accept your brand’s messaging when they can watch it without going through the additional steps of pausing their Spotify stream or muting their latest Netflix binge” (Breaux 2018). Counselling fellow marketers dismayed by the muting of their autoplay videos, the same advertizing guru compares its technique to that of a speaker who “[moves] closer to the intended recipient” in order to “[whisper] [….] ideas in their ear?” (Breaux 2018).[13] If radio could be indicted by Adorno (2002: 94-96) for projecting an illusion of “disinterested, impartial authority” while funnelling a smoothed-out stream of hate-politics and product-endorsement directly into the defenceless ears/homes of the masses, then what of the operation of a constantly rolling “feed” whose political messaging and advertising have both been designed to “speak” surreptitiously and yet specifically, to your interests, credit rating and prejudices? From sidebars and abandoned windows, the liquid voice of inaudibly voiced video trickles into our consciousness, via our fractally distracted peripheral vision. Chatting away as soon as a hovering cursor activates its kinetic autoplay stream, it addresses us in our most intimate settings: our beds, our breakfast tables, our pockets. And yet while there undoubtedly is a two-way informational flow afoot here (our details, purchases, pauses, our keystrokes, our eye-movements are being logged), the flow of speech is singularly (Schmitt would say dictatorially) unidirectional.

The supersmooth voiceover to 60 Million Americans deploys all of the locationless, sourceless, minimally material acousmatic’s coercive power. The micro-video’s nonvoice completes and extends this process. Hypostatizing the acousmatic effect, it removes all trace of sonorous materiality, specific embodiment and the relationality it implies. The voiceover attenuates the listener’s interpretive agency; the micro-video’s unvoice forecloses it altogether. Critical autonomy is diminished. Even, arguably, “readerly sovereignty”. Thus voided of the capacity to critically analyze the rhetoric we are fed, irradiated by pseudo-celestial light and comfortably ensconced in an always-already familiar and aspirational grotto to globalized hipsterdom, we may be bamboozled into buying in to a nebulous, noxious concept of liquid citizenship. But hopefully—in the instant of our exit from the immersive, seductive, New Eelam installation and before we have subscribed to sovereign citizenship—we are given cause to pause. New Eelam’s multi-modal liquid voice is the channel by which this cross-sensory bewitching is achieved. It is the means by which its fantasy of individual sovereignty and smooth exit is made to seem real, unmotivated, familiar and benign. We quit the space of the construct and the spell lifts—leaving us, hopefully, more alert to the manipulations of voice and nonvoice elsewhere, everywhere in our midst.

Sarah Hayden is associate professor of literature and visual culture at the University of Southampton and leads the AHRC Leadership Fellowship project “Voices in the Gallery.” She is author of Curious Disciplines: Mina Loy and Avant-Garde Artisthood (2018) and coauthor (with Paul Hegarty) of Peter Roehr — Field Pulsations (2018).

References

Abbate, Carolyn (1988) “Debussy’s Phantom Sounds.” Cambridge Opera Journal 10: 1, 67-96.

Andrejevic, Mark (2018) “ ‘Framelessness,’ or the Cultural Logic of Big Data” in Michael S. Daubs and Vincent R. Manzerolle (eds.) Mobile and Ubiquitous Media: Critical and International Perspectives. New York: Peter Lang, pp. 251-267.

Belinfante, Sam and Joseph Kohlmaier (eds.) (2016) The Listening Reader. London: Cours de Poétique.

Bonnet, Francois (2016) The Order of Sounds: A Sonorous Archipelago. Falmouth: Urbanomic.

Bratton, Benjamin (2015) The Stack. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Breaux, Paige (2018) “Marketing on Mute: The Case for Silent Video and Captioning in Video Content.” October 12. https://www.skyword.com/contentstandard/marketing/marketing-on-mute-the-case-for-silent-video-and-captioning-in-video-content/#

Bucknell, Alice, and Christopher Kulendran Thomas (2019) “In Conversation: ‘New Eelam: Bristol’.” Mousse magazine: Conversations. http://moussemagazine.it/christopher-kulendran-thomas-new-eelam-bristol-spike-island-bristol/

Cavarero, Adriana (2005) For More than One Voice: Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression, trans. and intro by Paul A Kottman. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP.

Chion, Michel (1994) Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. NY: Columbia UP.

Chion, Michel (2017) Words on Screen, ed. and trans. by Claudia Gorbman. New York: Columbia UP.

Connor, Stephen (2000) Dumbstruck: A Cultural History of Ventriloquism. Oxford: Oxford UP.

— (2014) Beyond Words: Sobs, Hums, Stutters and other Vocalizations. London: Reaktion.

Dale Davidson, James, and William Rees-Mogg (1997) The Sovereign Individual: Mastering the Transition to the Information Age. New York: Touchstone.

Doane, Mary Ann (1980) “The Voice in Cinema: The Articulation of Body and Space.” Yale French Studies 60, 33-50.

Dolar, Mladen (2006) A Voice and Nothing More. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Elden, Stuart (2013) “Secure the volume: Vertical Geopolitics and the Depth ofPpower.” Political Geography XXX. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.12.009

Facebook for Business (2016a) “Video Adverts: Testing What Works for the Mobile Feed.” April 20. https://www.facebook.com/business/news/building-video-for-mobile-feed

Facebook for Business (2016b) “Capture Attention With Updated Features for Video Ads.” February 10. https://www.facebook.com/business/news/updated-features-for-video-ads

Facebook Newsroom (2019) “Banning More Dangerous Organizations from Facebook in Myanmar.” February 5. https://about.fb.com/news/2019/02/dangerous-organizations-in-myanmar/

Forbes Agency Council (2018) “Sell It Without Sound: Nine Ways To Capture Attention With A Muted Video,” Oct 31. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2018/10/31/sell-it-without-sound-nine-ways-to-capture-attention-with-a-muted-video/

Hern, Alex and Jim Waterson (2020) “Mark Zuckerberg criticised by civil rights leaders over Donald Trump Facebook post,” Guardian, June 2. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/jun/02/mark-zuckerberg-criticised-by-civil-rights-leaders-over-donald-trump-facebook-post

Hirschman, Albert O (1970) Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, And States. Harvard: Harvard UP.

Horkheimer, Max and Theodor Adorno (2002) Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments, ed. Gunzlin Schmid Noerrr and trans. Edmund Jephcott. Palo Alto: Stanford UP.

Isaac, Mike (2016) “Facebook Profit Nearly Triples on Mobile Ad Sales and New Users.” New York Times, July 27. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/28/technology/facebook-earnings-mobile-ad-revenue.html?module=inline

Issac, Mike, Cecilia Kang and Sheera Frenkel (2020) “Zuckerberg Defends Hands-Off Approach to Trump’s Posts.” New York Times, June 2. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/02/technology/zuckerberg-defends-facebook-trump-posts.html

Kane, Brian (2014) Sound Unseen: Acousmatic Sound. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Kulendran Thomas, Christopher (2017a) “60 Million Americans Can’t Be Wrong,” in Size Matters! (De)Growth of the 21st Century Art Museum, eds. Beatrix Ruf and John Slyce. London: Koenig, pp.96-115

— (2019) NE_MV_01-08. Micro-video Series.

— (2016-18) 60 Million Americans Can’t Be Wrong. Film.

— (2017b) Press Release: Rome, A Tale of a Tub, September 18 2017- January 28 2018. http://a-tub.org/onsite/rome-christopher-kulendran-thomas/-

Labelle, Brandon (2014) Lexicon of the Mouth: Poetics and Politics of Voice and the Oral Imaginary. NY: Bloomsbury.

Li, Xinghua (2011) “Whispering: The murmur of power in a lo-fi world.” Media Culture & Society 33: 1, 19-34.

Maheshwari, Sapnia and Katie Benner (2016) “Making Video Ads That Work on Facebook’s Silent Screen.” New York Times, Sept 25. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/26/business/media/making-video-ads-that-work-on-facebooks-silent-screen.html.

Mayes, Kelly (2013) “An Easier Way to Watch Video.” Facebook Newsroom, September 12. https://newsroom.fb.com/news/2013/09/an-easier-way-to-watch-video/

Middleton, Peter (2005) Distant Reading: Performance, Readership, and Consumption in Contemporary Poetry. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Mozur, Paul (2018) “A Genocide Incited on Facebook, With Posts From Myanmar’s Military.” New York Times, October 15. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/15/technology/myanmar-facebook-genocide.html

Neumark, Norie (2017) Voicetracks: Attuning to Voice in Media and the Arts. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Parasram, Ajay (2012) “Erasing Tamil Eelam: De/Re Territorialisation in the Global War on Terror.” Geopolitics 17:4, 903-925.

Patel, Sahil (2016) “85 percent of Facebook video is watched without sound.” Digiday, May 17. https://digiday.com/media/silent-world-facebook-video/

Pettman, Dominic (2017) Sonic Intimacy: Voice, Species, Technics (Or, How to Listen to the World). Stanford: Stanford UP.

Rangan, Pooja (2017) “Audibilities: Voice and Listening in the Penumbra of Documentary: An Introduction.” Discourse 39:3, 279-291.

Riley, Denise (2004) “ ‘A Voice Without A Mouth’: Inner Speech.” Qui Parle 14: 2, 57-104.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques (2003). The Social Contract and Discourses, trans. by G.D.H. Cole, revised and augmented by J.H. Brumfitt and John C. Hall, updated by P.D. Jimack. London: Everyman

Schwab, Charles (2016) The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

Silverman, Kaja (1988) The Acoustic Mirror: The Female Voice in Psychoanalysis and Cinema. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana UP.

Steyerl, Hito (2009) “In Defence of the Poor Image.” e-flux journal 10. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/

Wark, McKenzie (2004) The Hacker Manifesto. Harvard: Harvard UP.

Watlington, Emily (2019) “Critical Creative Corrective Cacophonous Comical: Closed Captions.” Mousse 68. http://moussemagazine.it/critical-creative-corrective-cacophonous-comical-closed-captions-emily-watlington-2019/

Weizman, Eyal (2002) “The politics of verticality.” http://www.opendemocracy.net/ ecology-politicsverticality/article_801.jsp

Winner, Langdon (1986) The Whale and the Reactor. A Search for Limits in the Age of High Technology. Chicago. University of Chicago Press.

Wong, Julia Carrie (2020) “Facebook declines to take action against Trump statements”, Guardian, May 30th. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/may/29/facebook-trump-twitter-social-media-us?ref=nl-rep-a-bgr