This is the second part of an interview of R.A. Judy conducted by Fred Moten in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, over the course of two days, May 26-27, 2017. The first half of this interview appears in boundary 2, vol. 47, no. 2 (May 2020): 227-62.

Fred Moten: I want to return again, now, to the question concerning the fate of (Dis)forming the American Canon. The question of the fate of how it will be read in the future is obviously connected to the question of how it was read when it first came out. So, let’s revisit a little bit the reception and maybe think in a very specific way about the different ways in which it was received in different disciplines and in different intellectual formations.

RA Judy: Well, yes my earlier response to the same question focused on the idea of the book; that is, how that idea was received or not received in the discipline or field of black studies. In fact, the book had quite a different reception in the fields of cultural studies, comparative literature, and what was then being called critical race studies, or what became known as critical race theory and Africana philosophy. In some sense, this was understandable, given that I am a comparativist, and it was composed as a comparativist essay meant to be a bringing of the issues of what you and I call Black Study into the ambit of comparative literature, even though it ended up being marketed as a particular kind of Afro-centric work, which it never was, at least not in the political or academic position of Afro-centrism. For instance, the first chapter of the book which is a very careful critique and analysis of the formation of black studies, is about the university and the formation of the university, and McGeorge Bundy’s intervention at that important 1977 Yale seminar on Afro-American literary theory, which Henry Louis Gates and Robert Stepto were instrumental in organizing as a sort of laying of the foundation of what would become African American Studies. Bill Readings in his University in Ruins, found that chapter to be an important account, anticipating the neoliberalization of the university as he was trying to analyze it, and his taking it up became important; it led to not only a citation in his book, but other work that I began to do in boundary 2 and elsewhere. So that’s one point of, if you will, positive reception where (Dis)forming was taken up. The fourth chapter, “Kant and the Negro,” got a tremendous amount of positive reception and prominence, and was even been translated into Russian and was published as an essay in Readings’ pioneering online journal Surfaces out of the University of Montreal.[1] And then it got republished by Valentin Mudimbe in the Journal for the Society for African Philosophy in North America (SAPINA) in 2002. “Kant and the Negro” circulated widely and it got a great deal of attention from people like Tommy Lott, and Lucius Outlaw, and Charles Mills. In other words, it was well received and proved to be an important piece in the area of African and Africana philosophy. Lewis Gordon, as a result of that work, and this is when I was still very much involved with the American Philosophical Association, ended up producing one of my pieces in his Fanon Reader.[2] In Cynthia Willett’s Theorizing Multiculturalism, there’s a prominent piece, “Fanon and the Subject of Experience,”[3] which kind of refers to one of the points I was trying to make yesterday about individuation. I want to read to you, if I may, the opening passage from that 1998 essay:

If we accept along with Edward Said that was is irreducible and essential to human experience is subjective, and that this experience is also historical, then we are certainly brought to a vexing problem of thought. The problem is how to give an account of the relationship between the subjective and historical. It can be pointed out that Said’s claim is obviously not the polarity of the subjective and the historical, but only that the subjective is historical. It is historical as opposed to being transcendent, either in accordance with the metaphysics of scholasticism and idealism, or the positivist empiricism of scientism. Yet to simply state that subjective experience is also historical, is not only uninteresting, but begs the question, “how is historical experience possible?” The weight of this question increases when we recall the assumption that the subjective is essential to human experience. Whatever may be the relationship between subjective and historical experience, to think the latter without the former is to think an experience that is fundamentally inhuman. Would it then be “experience”? That is, to what extent is our thinking about experience, even about the historical, contingent upon our thinking about the subject?

This is how, then, I take up the approach to Fanon as bringing us to this question. And we see that already there I’m trying to interrogate the inadequacy of the notion of the subject in accounting for the question of the historical nature of thinking-in-action, and that thinking-in-action always entails what we were talking about yesterday as the individual as discrete multiplicity in action. And how we think about it, and that’s where I’m trying to go with the second book which I’m sure we’ll talk about in a minute, and also the third book with Fanon, but that’s coming out of (Dis)forming as a formulation of individuation. Again, this is in the Willett piece that is an elaboration on what is at the crux of the project in “Kant and the Negro.” That is to say, it’s not that there is no discrete articulation of multiplicity that is fundamental to what we may consider experience, or what others might call the situation or the situational; the question is how we think about it, and whether the current discourse we have of it is adequate or even if its’s possible to still think about it once we dispense with that discourse. I mark the latter by trying to make a differentiation between what I consider the historical formation of bourgeois subjectivity as a particular way of understanding the relationship between thinking and history, of thinking the event, and other formations that I think are inadequately accounted for because we don’t have the language for it, and that’s the point of the current work, is to try to formulate such a language. Tommy Lott, as well found “Kant and the Negro” very important; I ended up doing a piece in his volume, A Companion to African-American Philosophy, and I believe it was called . . . Yes! “Kant and Knowledge of Disappearing Expression.”[4] In that piece I, at Tommy’s invitation, took up the philological problematic that Ben Ali posed as an important case or instance of not really the limitations of Enlightenment theories of the subject, but also as pointing to other possibilities as a concrete instance in Ben Ali’s stories.

FM: So, this leads me to two questions, one that emerges from this different reception. It has to do with the relationship between black studies and other disciplines, specifically with comparative literature but also with philosophy, and then with mathematics, and, finally, with their convergence. So, the question is what do those disciplines have to do with black studies? How does that relation manifest itself, not only in your work but in a general way? So, that’s one question. The other question, which is connected to it, is this: once one begins to think about the confluence of black study, mathematics, philosophy, how does that coincide with a project, or at least what I take to be part of your project, which is not a renewal or a rescue of the subject of experience but is, rather, a new way of thinking the the relation between individuation, as you have elaborated it here, and historical experience?

RAJ: I’ll first make a remark about “the subject of experience.” In the Lott piece and in another piece that I did at the invitation of Robert Gooding-Williams in the special issue of the Massachusetts Review he edited, on Du Bois, “Hephaestus Limping, W.E.B. Du Bois and the New Black Aesthetics,”’[5]in which the work of Trey Ellis is my point of reference, I talk about what I designate, the subject of narrativity, as distinct from the subject of experience, or the scientific subject. And in an effort to try to elaborate how I think what’s at play in a whole series of texts, Ellis’ Platitudes and others, the Ben Ali texts, I’ve gone on to other novels and such that are doing this thing, including Darius James’ Negrophobia, and Aṭ-ṭāhir wa ṭṭār’s book that has yet to be translated into English, Tajriba fī al-‘ašq (Experiment in Love) to Ibrahīm al-Konī’s work, and of course Naguib Mahfouz’s Tulāthīya (The Cairo Trilogy). In each of these cases, I’m trying to show that what’s at work is the formulation of a kind of subject, a representation of it; in calling it the subject of narrativity, that’s a precursor to what I referred to yesterday as the subject of semiosis. And in that working through, the thinking of Charles Sanders Peirce is really central and instrumental. I mentioned Vico earlier, and Spinoza, Peirce and Du Bois, these are principal texts for me in the Western tradition, as is al-Ghazālī, as well as the Tunisian writer, al-Mas’adī, as well as Risāla al-ghufrān by al-Ma’arrī, and the work of al-Jāḥiẓ, particularly his Kitāb al-hayawān (Book of the Animals), and Kitāb al-bayan wa a-tabiyīn (Book of Eloquence and Demonstration). This is kind of like my library, as it were. And Peirce, to stay focused on the question about the philosophical and the mathematical, in his effort to try to arrive at a logical-mathematical basis for human knowledge in a very broad sense, which he calls “semiosis” around the same time de Saussure discovers “sémiologie, gives us a very specific conceptualization of community in narrative, community in process, whereby truth is generated in the dynamics of ongoing open-ended signification. I come to Peirce through my formation as a comparativist— Peirce’s work was of some importance in Godzich’s Comparative Literature Core Seminar at the University of Minnesota in a particular kind of engagement with Husserl, Derrida and Lyotard and others who had looked over at Peirce—but more importantly through Du Bois. In reading through Du Bois’ student notebooks, I find clear traces . . . echoes of Peirce. Although Peirce isn’t named in those note books, Royce, with whom Du Bois studies and whose theory of community he was critically engaged in, was. And Royce expressly admitted he was using Peirce’s semiosis in elaborating his theory of community. This is one of the portals of the mathematical concern for me, with respect to the question of individuation, minus Peirce’s agapism; that is to say, minus Peirce’s teleology. Once again, Du Bois instructed me in a major way; this time to be critical of teleology, understanding the fact that it is the persistence of the teleological that leads to particular ethical impasses, or what I like to call the crisis in and of ontology. A crisis in which the event of the Negro always highlights, always marks the break, the gap, the hole in the ontological project. So, that even the invention of the Negro in seventeenth-century legislation of slavery is an effort to try and fill that gap. And that’s where I begin to situate the question of what you like to call Black Study. Now, that’s my way of thinking, to begin to address your question about the different disciplinary responses. To my recollection something begins to happen around the work of black philosophy in the late 1960s and early 1970s. I’m thinking of the of work Nathaniel Hare and what he began publishing in The Black Scholar from its inaugural issue in November 1969, where we find Sékou Touré’s “A Dialectical Approach to Culture,” and Stanislas Adotevi’s “The Strategy of Culture.” The next year in volume 2, issue 1 of that same journal, we find the remarkably provocative the interview with C. L. R. James, in which he challenges the then prevailing identitarian notion of black study. That same issue had an essay that, at the time—1970 when I was a sophomore in High School still aspiring to be a physicist and astronaut—so caught my attention that I’ve keep a copy of it, S.E. Anderson’s “Mathematics and the Struggle for Black Liberation,” in which he states something to the effect that “Black Studies programs then being instituted were white studies programs in blackface aimed at engendering American patriotism through militant integrationism. What he argued for instead was a revolutionary humanism. My point is there was a radical intellectual tradition that lay the foundations of much of what is being done now as Black Study, that most certainly was foundational to my thinking and work. Essays published in The Black Scholar during the early 1970s that still reverberate with me are

Abdl-Hakimu Ibn Alkalimat’s “The Ideology of Black Social Science,” Sonia Sanchez’s “Queens of the Universe,” Dennis Forsythe’s “Frantz Fanon: Black Theoretician,” and George Jackson’s “Struggle and the Black Man.” Just as important are people like Cedric Robinson, Tommy Lott and Lucius Outlaw, who are approaching the question of blackness in a vein that I think is a continuation of what Du Bois was trying to do, and what people like Harold Cruse and Alain Locke were trying to do.

FM: Would you include the folks who were doing a certain kind of theological reflection that at some point came to be known as black liberation theology, people like James Cone, and even his great precursor Howard Thurman? Was that work that you were attuned to at that same time too? Because they were concerned with these kinds of ontological questions as well.

RAJ: Yes, I was reading James Cone and Howard Thurman; and before that, William Jones’s 1973 book, Is God a White Racist? While they were concerned with the same questions, they were emphatically still invested in the teleological. But yes, I include that, although that part of the reception of (Dis)forming is complicated—I’m thinking of Corey T. Walker’s reading of it— because the canon that they’re trying to form is—what can I say—is around the church, and around the theological questions of the church and the performance of community in the church, the church as community. It is post-secular in a way that (Dis)forming is not. And so, the question of style is an important question for me and the question of the forms that are being explored is an important question for me, and I couldn’t follow them in those forms. Significantly enough, Hortense Spillers does both anticipate and follow because one of Spillers’ earliest concerns is to understand the genealogy of the sermon, in all of its various forms including its forms among early English Protestants and its rhetorical structures. You can see this in what she’s doing with Roland Barthes and the question of structuralism in “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe.” You can also see it in her essay on Harold Cruse, “The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual; A Post-Date,” a long meditation on the question of style and the analogy between musical style, and the question of whether or not the black intellectual can be capable of a certain kind of thinking, which, by the way, is a very interesting engagement with Althusser and Balibar’s Reading Capital. “America and Powerless Potentialities”[6] considers Spillers’ engagement with these questions along these lines in tandem with Du Bois’ 1890 Harvard commencement speech. So yeah, there’s a certain engagement, but one that is, let us say, appositional, a certain . . . I have an allergy to the teleological, to the extent that I keep trying to make sure that I can ferret out its persistent or residual workings in my own thinking.

FM: Yeah, I was thinking of them, just because sometimes when I go back and look at that stuff, it seems like teleology gives them the sniffles sometimes, too, you know?

RAJ: Cone’s work, for example, has led to a very particular swing over the past 8 years now of trying to reclaim Du Bois as a Christian thinker. I’m thinking, for instance, of work by Jonathon Kahn, who takes into account the arguments of Cone, but also Dolores Williams and Anthony Pinn, in his reading of Du Bois work. Or that of Edward Blum and Phil Zuckerman. The work of Cone and company is there yes, but in a particular kind of way, as that with which I’m flying but out of alignment. On the issue of the disciplines, it’s very interesting that (Dis)forming was well-received by African American philosophers, such as Lott and Outlaw, Paget Henry and Lewis Gordon, Robert Gooding-Williams, Tony Bogues and Charles Mills, all of who are doing significant work, trying to take up these issues, as issues relating to, forgive the phrase, the general human condition. These issues, referring to the problematics of blackness, or black study, where black study is about a particular tradition of thinking and thinking in the world, proved to be quite enabling, and proved to be one of the initial fronts, or at least openings, for a, I don’t want to quite simply say “revitalization” because that gives a certain weight, perhaps disproportionately, to what was happening at San Francisco State in 1968-69, although I think it’s important when you go over the material being generated in the 1980s and 1990s to bear in mind that that movement in ’68 initiated by the Third World Liberation Front—a coalition of the Black Students Union, the Latin American Students Organization, the Filipino-American Students Organization, and El Renacimiento —was expressly predicated upon Fanon’s understanding of the prospects of a new humanism, and so its ambition was to try to model, what would be broadly speaking, a new humanism, which is why that is going to eventually lead to the creation of what I believe was the first autonomous department of Black Studies and Ethnic Studies under Hare’s directorship. It’s no small matter that the Black Panther Party’s National Minister of Education, George Mason Murray, was central to that movement. So, that initial institution of Black Studies conceived itself, presented itself, and aspired to be a reimagining of the history of humanity along a very specific radical epistemological trajectory. Now, how that gets lost is another question, and we can talk about the difference between San Francisco State in 1968 and the establishment of a black studies program at Yale in the same year. But, to stay focused, I don’t want to say that what Lucius Outlaw, Tommy Lott, Lewis Gordon, Charles Mills, Tony Bogues and others are doing is simply a revival of San Francisco State in 68; although I do think it is taking up that epistemological project. We see this, for instance, with Hussein Bulhan’s 1985 book, Frantz Fanon and the Psychology of Oppression, which was trying to lay down a radical humanist conception of humanity predicated upon psychoanalysis, in that way, taking up Lacan’s anti-philosophy. Not so much the anti-philosophy, but trying to make philosophy do something different, and think about the individual in ways that was more complicated and more adequate than the theory of the subject that people were rallying against. All of those were efforts that come out of Fanon and were expressly thinking about the question of, what you and I call Black Study, as an instantiation of the question of the human, in which the particularities of the style of response of black people to certain things, the forms of thinking that those we call “black” were engaging in, said something, or had resonances, broad resonances. Without, then, just simply assuming to occupy the position of the normative subject, the transcendental subject, into which the hypostatized bourgeois had been placed in the philosophical discourse of the Enlightenment: the convergence of the subject of science with that historical bourgeois subject, or the subject of knowledge with that historical bourgeois subject, or even the subject of experience with that historical bourgeois subject, or even the subject of the spectacle, the subject who is seeing Merleau-Ponty tries to problematize. That Black Study attends to those particularities of style and thinking without trying to simply have the “black” occupy that subject position. The aim, instead, is to open up the project of thinking so that there isn’t that positionality at all. This goes back to what we were talking about earlier as displacement, that the Negro has no place, and is not about making place. But I like your phrasing, the “consistent and intense activity of displacement.” So, they’re doing that, these black philosophers, and they open up a front, they open up a Black Studies, in a way that retrieves the momentum of 68’ in a powerful way. And that work finds a particular institutional toehold. Bulhan will subsequently establish the Frantz Fanon University in Somaliland in, I think, 2010. And at Brown University’s Africana Studies Department, in contrast to what takes place at Temple and the creation of Africana Studies there, will include the work of Lewis Gordon, Tony Bogues, and Paget Henry . . . So, the reception of (Dis)forming in those quarters was predictable. Those quarters were quarters of important experimentation, that have played no small role in the kind of transformation we have seen in Black Study, where increasingly this kind of work is becoming important. What’s interesting is what begins to occur in this century. One can begin to look at works that you’re starting to produce around 2000, where the revivification of that initial articulation I’m talking about, is taken up in poetic discourse. And in that form, begins to find its way, slowly—and it’s a struggle— into traditional institutional programs of what we now refer to as African American or African Studies. But it only begins to do so, because we’re still looking at a situation, if we look at Harvard, or Yale, or Princeton, or UC San Diego, we’re looking at programs that are still pretty much organized around the sociological model, that aren’t taking up these questions in this way. So that’s how I understand the institutional relationships, the disciplinary relationships, and account for the difference in reception of (Dis)forming.

FM: The way you’re characterizing this raises a couple of questions for me, because I’m thinking specifically now of a particular work by Du Bois, which you first made available to contemporary readers some years ago, “Sociology Hesitant,” in which it appears to be the case that Du Bois is making a distinction within sociology, or between modes of sociology, or between possible modes of sociological reflection. It is that distinction we talked about a little bit earlier, a distinction regarding the difference between the calculable and the incalculable. My understanding of the essay is that it allows for maybe a couple of different modalities of the sociological, one that operates along a certain kind of positivist axis, and another that would take up what he talks about under the rubric of “the incalculable,” which would allow us to pay attention to these modalities of style you touched on earlier. Well, in that essay he talks about it in relation to the activities of the women’s club, but we could imagine he might also assert those activities as extensions of the church service as a scene in which the exegetical and the devotional are joined and shared. But the point is that there are a couple of different modalities of sociological reflection, one of which would entail something you would talk about under the rubric of the humanistic, or the philosophical, or the literary.

RAJ: A prefatory remark about how I came to that essay. I just handed you an envelope from the W. E. B. Du Bois Papers at University of Massachusetts, Amherst, dated, as you can see January 20, 1987. At that time, reading through the scholarship on Du Bois, I encountered many references to “Sociology Hesitant,” which reported its being lost. And I wanted to read this piece so badly because of the references. Anyway, in the course of reading through the microfilms of the W.E.B. Du Bois Collection, at the University of Massachusetts Amherst Library, which the University of Minnesota Library owned, I came across a reference to “Sociology Hesitant,” in Robert W. McDonnell’s Guide and found it there in the microfilms. So I wrote the Special Collections and Archives office at Amherst, requesting the certified copy of it you’ve just looked at. I was like blown away when I actually read the essay, and blown away for the reasons that you’re posing right now. This does indeed go to our remarks earlier about individuation and what I was trying to say about the issues of paradox. In “Sociology Hesitant,” which is written in 1904-1905 in the context of the St. Louis world’s fair, Du Bois critiques sociology for a confusion of field and method. He traces that confusion back to Comte’s Positivism which, reducing the dynamics of human action to axiomatic law, postulates society as an abstraction; something that is “measureable . . . in mathematical formula,” as Du Bois puts it. Indeed, a fundamental dictum of Comte’s Positivism is that there is no question whatever which cannot ultimately be reduced, in the final analysis, to a simple question of numbers. And in this regard, we should bear in mind that his sociology entailed two orders of mathematical operations, which he calls “concrete mathematics” and “abstract mathematics” respectively. Du Bois tracks how this axiomatic arithmetization of human action gets deployed in Herbert Spencer’s descriptive sociology, and Franklin Gidding’s theory of consciousness of kind, as well as Gabriel Tarde’s theory of imitation. Regarding these various attempts at reducing human action to mathematical formula, he writes, “The New Humanism of the 19th century was burning with new interest in human deeds: Law, Religion, Education. . . . . A Categorical Imperative pushed all thought toward the paradox; the evident rhythm of all human action; and the evident incalculability in human action.” The phrase, “New Humanism,” translates Friedrich Paulsen’s designation, “Neue Humanismus,” which he also conflated as “Neuhumanismus”,” and so is usually rendered in English as “Neohumanism.” Paulsen coined the term in 1885 to designate the nineteenth century German cultural movement stemming from Wilhelm von Humboldt’s and Friedrich August Wolf’s ideas that classical Greek language and literature was to be studied because of its absolute value as the exemplary representation of the idea of man.” The Neohumanists held that nothing was more important than knowledge of Greek in acquiring self-knowledge (Selbsterkenntnis) and self-education (Selbstbildung). This Hellenophilia, bolstered by Christian Gottlob Heyne’s “scientific” philology, informed Friederich Gauss’s work in the arithmetization of analysis. We know about Du Bois’ German connections. His usage of the phrase strongly suggests that he’s thinking about the arithmetization of analysis, and he talks about what he calls “the paradox of Law and Chance” in terms of physics, and the developments of physics, and those who try to model the social on the physics. He maintains that the very project of the measurement exposes that there is something that is working here that is not measureable, that cannot be reduced to arithmetic expression, pace Comte’s positivist dictum. Du Bois effectively argues that Comte is wrong about mathematics. It does not tell us everything.” What it does is tell us a great deal about the physical world, even the physical nature of the human if we want to bring in the biological. But, while it tells us all of that, what keeps being exposed in the course of its discoveries is something that exceeds it in a way that really echoes Dedekind’s understanding of arithmetic definition and the limit problem, where something else emerges; which is what Du Bois pointedly calls, “the incalculable.” He proposes a different way of doing sociology. He says, “the true students of sociology accept the paradox of . . . the Hypothesis of Law and the Assumption of Chance.” They do not try to resolve this paradox, but rather look at the limit of the measureable and the activity of the incalculable in tandem, to, as it were, measure “the Kantian Absolute and Undetermined Ego.” Du Bois says this rather tongue-in-cheek because he’s continually challenging the Kantian proposition that this ego is not measureable to say that indeed we can say something about it and its traces, we just can’t say it in terms of numbers, we can’t count it. So, his proposition for sociology is one where we have the mathematical working and then we have these other incalculable activities. And in the space of the paradox, the break, he situates, 1) the event of human social organization; 2) that event can be seen from the perspective of a mediating discourse that will help mathematics recognize what it’s doing as an ontological project—which he wants to be critical of—and also will help chance appear in an important dynamic relationship to that ontological project. There is a way in which Du Bois is challenging not only Comte’s basing sociology so absolutely on arithmetic analysis but the predominate trend of statistical sociology—of which he was a leading practitioner, producing the second major statistical sociological study in the English language of an urban population, The Philadelphia Negro, in 1899— for, as he says in a 1956 letter to Herbert Aptheker, “changing man to an automaton and making ethics unmeaning and reform a contradiction in terms.” In that same letter, he effectively summarizes the critique of knowledge in “Sociology Hesitant” as the crux of his life-long intellectual project, or “philosophy,” as he calls it; which he characterizes as the belief that the human mind, human knowledge, and absolute provable truth approach each other like the asymptotes of the hyperbola. Although Du Bois attributes this analogy to lessons learned in High School mathematics, it is also a deployment or reference to the Poincaré asymptote, which is something he would have known very well as one of the premiere statisticians of his moment. The significance of Du Bois’ situating his thinking at the crux of paradox, the crossroad where the measurable and incalculable meet, to his thinking on the Negro is one of the things explored rather carefully in the book manuscript I’ve just finished, Sentient Flesh (Thinking in Disorder/Poiēsis in Black).

FM: Earlier you expressed a certain kind of critical skepticism with regard to the very idea of a mediating discourse, or a third discursive frame, or a conceptual frame from which to adjudicate between these two.

RAJ: Yeah, there I depart from Du Bois, hence, my remarks about the sociological, in the sense of the academic discipline.

FM: So, you’re not advocating or enacting in your work anything like what he might call the “truly sociological.”

RAJ: No, I am, but not in the sense of a normative disciplinary methodology, a unifying theory. Remember, Du Bois says “true students of sociology embrace the paradox.” I would paraphrase this as “true student of sociality,” because he is expressly arguing against “sociology” for not be capable of adequately studying the dynamic relationship between the ideological elements and the material practices constituting society. Anyways, when he says this, he is pushing against axiomatic absoluteness and not the tendency to generate law or axiomatic definition. The true student of sociality, then, is not hyper-invested in a transcendent disciplinary methodology, but rather in constantly moving along asymptotic lines. In that respect, I’m also taking up something that Du Bois does in his literary work. I offer as example, two texts: “Of the Coming of John,” and Dark Princess. One could pick more, including a wild piece of experimental writing that I found at Fisk back in 2011. In Sentient Flesh, I focus on “Of the Coming of John,” a very rich and important piece. I look at something he’s doing in that literary work, which is different from what he does, or let’s say stands in a particular kind of dynamic relationship to what he’s doing in his theoretical, sociological, political and editorial work. The nature of that relationship is indicated by his remarks in the 1956 Aptheker letter, but it is clarified in a piece that is arguably one of the scattered fragments he’s written that he alludes to there, in which he expressly theorizes the relationship between human mind and provable truth. That piece is the 56 page-long student essay he wrote in 1890 while studying at Harvard, “The Renaissance of Ethics,” for the year-long course, Philosophy VI, taught that year by William James. What one finds in that essay is a very sustained, very cogent critique of the history of modern philosophy from Bacon on. Actually, it begins with scholasticism to lay out what’s at stake in theistic teleology, and then talks about the extent to which the Galilean-Baconian revolution achieves a certain kind of transformation in the area of natural philosophy, the arithmetization of nature, but ethics lags behind. Ethics becomes metaphysics, and metaphysics just continues the teleological, and hence there is no renaissance of ethics that is comparable to what has happened in the physical sciences through arithmetization. Du Bois then claims the ascendency of the novel as evidence of what he calls the demand for a “science of mind” as the basis for a “science of ethics.” What I’m getting at with all of this is that what Du Bois is working towards in his account of the novel— and I would say also in the formal composition of The Souls of Black Folk —is illustrating there’s not so much a confrontation or a tension between, let us say, the mathematical and the poetic, but that they are working together. What I’m trying to point out is that, in Du Bois’ own account and performance, their working together, their relationship is not mediated by a transcendent third disciplinary discourse: the sociological. But rather, their working together is expressed in the activity of intellect-in-action, which is not disciplinary. In fact, I would say it is a thinking-in-disorder, which is what I’m calling “para-semiosis;” where semiosis is not a position—this relates to what I’ve said about the subject of narrativity—but is the activity of signification that is always multiple in its movements, multi-linear, and again even in terms of the individual expressions of elements, they themselves are multiple multiplicities; which are, as you say, “consistent and insistent.”

FM: Is what Du Bois calls the science of mind in “The Renaissance of Ethics” differentiated from what he calls true sociology? And if it is, is it differentiated at the level of its objects of analysis?

RAJ: Yes. And if you look again at “Sociology Hesitant,” he also makes that differentiation. They’re both speculative texts. And he’s calling for a different way of thinking. The distinction, is part of a distinction of his thinking. Du Bois is full of all kinds of contradictions, right? And in trying to follow that distinction, in “Sociology Hesitant,” he’s talking about the prospects of a scholarly discipline, and he’s arguing for the discipline to be better oriented. That’s how he begins. And the reason that discipline is poorly oriented is because it’s grounded in a particular kind of idealism. That’s his charge against Comte and Spencer, against Gidding and Tarde; they’ve postulated a totality, a whole, without any conceptualization of relationships between elements. And so they’re not actually studying the multiplicities that constitute human reality, they’re putting forward an abstraction, and it’s an abstraction that’s driven by Comte’s commitment to number, as I’ve already remarked. So, the discipline has to be corrected if it is to actually consider what is of importance in this moment of modernity and capitalism; and that is the ways in which . . . how socialities are being constituted. Du Bois’ point is to critique sociology, and when he says true students of sociology, he says if you’re going to do sociology, you would have to do it in a way that attends to the paradox. But the moment you begin to do that, then you’re doing something quite different from sociology as we understand it, because that’s going to take you, as it takes him, to questions about epistemology, about what’s the nature of intelligence, what’s the nature of thinking in the world, what is the nature of duty, what, indeed, is our theory of mind. He comes to these questions in “The Renaissance of Ethics” in the course of trying to understand duty in terms of interpersonal relationship, or reciprocity, sociality. What is the good and how do we get at the good? On that score, there is a very subtle, profoundly important move he makes. Taking on Hume’s theory of causality—according to which the human mind, incapable of directly observing causal relations only conceptualizes sequences of events, one following another—Du Bois argues that it’s all about structural process and movement, stressing the point that if one element in the process shifts, the relationship shifts, so that not even sequence is consistently necessary. He offers in illustration a grammatical example. If you change the term “bonus” in the phrase vir bonus (“good man”) to “bona,” the alteration changes the terms of relation—in accordance with Latin grammatical rule, making the adjective in this phrase feminine, bona, dictates that the noun vir (“man”) becomes mulier (“woman”). But this changes a great deal more, given the provenance of the phrase. In classical Latin, vir means interchangeably “hero,” “man,” “grown-man,” and “husband.” Vir bonus, “the good man,” belongs to the discourse of public conduct. In short, vir bonus is the virtuous man of masculine polity. If you feminize this statement of the virtuous political conduct, it becomes something else. This is no offhanded remark on Du Bois’ part—remember that for two years in his first job at Wilberforce, he taught Latin and Greek—and when you explore it in the context of the essay’s topic, renaissance of ethics, what he’s suggesting is a critique of the fundamentals of the millennia-long tradition of virtue ethics. Much of “The Renaissance of Ethics” is committed to deconstructing the phrase, summum bonum (“the highest “good”), which is Cicero’s Latin rendering of the Platonic /Aristotelian Greek term, eudaimonia. He’s saying that we must begin to reimagine what and how we conceive to be the human. He gives considerable emphasis to “how” we conceive; and that’s where the question of duty comes up. It’s in trying to think about how we can think duty that he starts to shift into questions about how we think about intelligence. Accordingly, he ends up with this call for the need of a science of mind.

FM: So, are you then saying at a certain point there is a convergence between true sociology and science of mind, insofar as true sociology’s actual object of study is mind?

RAJ: Yeah. And here’s where he’s following Comte. Comte’s whole positivist science is about epistemology, about the structure of knowledge. Du Bois point is that Comte is approaching the question of intelligence on a false premise. We have to understand and begin to think about it differently as a practice, which for Du Bois means attending closely to life practices: the multiplicities of discrete things that people do. He approaches these in a way that’s really quasi-structuralist. Here, there’s an echo of Aristotle, he begins to use Aristotelian terms and movement, beginning from there to track patterns and structures. We’re talking, then, about what is thinking, what is intelligence. What and how are we? So the statement about true students of sociology is somewhat ironic, as well as being critical and corrective. Spencer, Giddings, Tarde, and their respective disciples aren’t true students of sociology, if they were, they would do this. And if they did this, it’s would take them beyond the numeric, beyond just counting.

FM: So then, is the true student of sociology a scientist of mind?

RAJ: Well, I’m not prepared to say that. If one took Du Bois at his word, one could, in a certain way, say that. I’m not prepared to say it because there’s a great deal of slippage and movement in both these texts I’m referring to. As I say, they’re speculative. He’s reaching, he’s trying to find a way to give a sort of coherent and adequate expression to what he imagines to be the project. So I’m not prepared to say that the true student of sociology is a cognitive scientist. But I am prepared to say that in Du Bois’ conceptualization of what the nature of the project is, he’s not, in the end, positing sociology as a transcendent mediating discourse that’s going to make mathematics work with poetry. And so what I am saying is that in his performance—and this is where I take a cue for the idea I have of semiosis and para-semiosis—in his performance and the reaching for I’ve just described, in which he’s situating these things in a certain kind of relationship, this is where the thinking is taking place. What he calls intellect-in-action is what he’s reaching for, what he’s performing. What I’m saying, in addendum, is if we focus on intellect-in-action as process, as semiosis, and think about the problematic he is approaching, which is the problematic of blackness, in those terms, we arrive at what I call the poiēsis of blackness. The poiēsis of blackness is itself a process of thinking, of thinking in and with signification. We could very-well consider it a practice of Black Study.

FM: When we go to look for the poiēsis of blackness, when we seek it out as an object of study, where do we seek it out? In other words, let’s say that there must be slippage between ‘true sociology’ and ‘science of mind’; then, by the same token we could say that in spite of the fact that there is this precarious pathway from one to the other, that precarious pathway is a pathway that Du Bois takes, and that he encourages us to take, so that we are on our way, as it were, towards a science of mind, which would take up and be interested in, and be concerned with, while also enacting in that study, what you’re calling, after Du Bois, intellect-in-action, but what you would also call a poetic sociality. I want to hear you say a little bit more, and be a little bit more emphatic, about what the object of study is or whether there is, in fact, an object of study that can be differentiated from the mode of study. Where do we go to look for this intellect-in-action? Where do we go to look for this black poetic sociality? Am I right in assuming that where we go to look for it is in what you described earlier as these discrete multiplicities, which we are, in fact, enacting in that search?

RAJ: The poiēsis of blackness, and this is what I argue Du Bois performs, I want to be emphatic here, is process and object. It’s doing what it’s talking about. As I’ve already said, I paraphrase Du Bois’ term, intellect-in-action, as “thinking- in-action.” Hence, the title of my new book is, Sentient Flesh (Thinking in Disorder/ Poiesis in Black). There is an emphasis on disorder, precisely because this thinking is not already circumscribed—and here I have in mind Heidegger’s notion of the concept’s circumscription by order. But it’s a thinking that occurs in the fluidity of multiplicities, and in its articulation, articulates discrete orders that have a particular life in activity but aren’t eternal. They’re always on their way to the next. This is what Du Bois talks about as the asymptotes of the hyperbola, invoking the continuum hypothesis; that these things approach one another toward infinity without ever touching. Assuming human knowledge and provable absolute truth to be the hyperbola in Du Bois’ analogy, there’s a long discussion we can have about ethics being the point at the center of the hyperbola where the transverse axis, “law,” and the conjugate axis, “chance,” meet. Any such point of conjunction becoming what Comte calls états, “states,” and we can call orders of knowledge. We might, in that Comtean way, understand these états as expressions that articulate specific institutions— now I’m speaking very much like Vico— that have material traces, that we can call “culture” or “civilization,” we have all kinds of names for these, but that are fundamentally dynamic, and so are not enduring in themselves. What endures is the process. So, the object is precisely these discrete multiplicities at many registers. We could talk about this in terms of sets. But as the object of knowledge and analysis, it is so performatively. One does not come at that object from someplace else, but one is doing the very thing that one is talking about, and so it becomes a way of attending to one’s thinking in action which I’ve called elsewhere “eventful thinking.”

FM: You just said it is a way for one to attend to one’s thinking in action. But earlier you spoke of thinking-in-action, intellect-in-action, discrete multiplicity, in what might be called set-theoretical terms. Is it, in fact, more accurate to say that it is the individual who is engaged in both the enactment and the study of intellect-in-action?

RAJ: It’s the individual, as I said in our earlier discussion of this, in relation; and it’s a dynamic relation. So, it’s not the individual standing alone; it’s not the individual as one, but the individual as an articulation of the semiosis in tandem with other individuals. And I put it that way because one must be careful . . . I’m not arguing for what Husserl calls the transcendental subject, where there is this notion of the articulation of the individual in relation to others, but it’s raised up to another, again, transcendent level at which there is a particular kind of integrity that then filters down. There is no transcendence here. By my reading, there is no transcendent position in what Du Bois is trying to do, and what I’m trying to do with what Du Bois is trying to do. The reason there is no transcendent position in what Du Bois is trying to do specifically, and this is expressly in his work, is because his immediate object of concern is “the Negro.” And he’s trying very hard to understand how the Negro is, what the Negro is.

FM: When you say “the Negro,” do you mean a Negro?

RAJ: No. Because Du Bois doesn’t mean a Negro. He’s talking about what one could call an event. And when he’s asking how it is, he’s trying to understand the situation of the event. In other words, he’s trying to understand the ways in which what we would call modernity has articulated this event, and not only what that event is, but how that event is articulated, how that event works, how it acts. What is activity within, around that event? Or to put it differently, this is why when he talks about it in terms of “the souls of black folks,” he’s not being Hegelian, he’s not talking about Geist. He’s concerned with the ways in which that event, in its historical specificity, permits, enables, and encourages particular sorts of activity; and he wants to know what that activity tells us or says about the human condition or possibility. Nahum Chandler talks about situatedness at that level in Du Bois, and what he says it does is, “engenders a paraontological discourse.” I want to avoid, for reasons we can go into, the paraontological. Some of the reason has been indicated in what I’ve been saying about Du Bois’ critique of teleology, his critique of the limitations of number, which has to do with eschewing a very specific investment in a transcendent discourse of being qua being. And I’m thinking very specifically about the provenance of the term “paraontology.” Oskar Becker coins the term, “Paraontologie,” or “paraontology” as a corrective augmentation to Heidegger’s phenomenological analysis. A mathematician, Becker was also one of Husserl’s students, along with Heidegger at Freiburg. In fact, both served as his assistant, and his expectation was that the two of them would continue his phenomenological research, with Heidegger doing so in the human sciences and Becker in the natural sciences. Anyway, Becker coined the term in his 1937 essay, “Transzendenz und Paratranszendenz” (“Transcendence and Paratranscendence”), to counter Heidegger’s displacement of Husserl’s eidetic reduction in favor of the existential analytic. Becker tries to counter Heidegger by reconstructing eidos as the primordial instance when the possibility of interpretation is presented. He calls this primordial presentation of presentation a Paraexistenz, “paraexistence,” and its phenomenological investigation is the Paraontologie, “paraontology.” This is a challenge to Heidegger’s claim that existential analytic of Dasein brings us to fundamental ontology. Becker wishes, thereby, to redeem the possibilities of a super discourse of being qua being. A key element in his argument with Heidegger is the identification of mathematics and ontology. Along those lines, he was making a particular kind of intervention into set theory. When Lacan some years later begins to pick up the issues of set theory before moving onto topology, he deploys a term that is very similar in connotation to Becker’s paraontology, par-être, “the being beside.” But even Lacan’s articulation of par-être, as a way of trying to move against the philosophical discourse of ontology— psychoanalysis as the anti-philosophy—runs the risk, as Lorenzo Chiesa has said, of slipping back into the ontological. Of course we know Badiou, who follows Lacan expressly in this, like Becker, identifies mathematics with ontology, maintaining that while mathematics does not recognize it is ontological in its project, philosophy is there to recognize it and to mediate between it and poetry. This is one of the reasons I have a problem with paraontology, it takes us back to the position wherein the discourse of philosophical ontology is reaffirmed as dominant. While I trouble Chandler’s sense of the situatedness of the Negro generating the discourse of the paraontological, I concur with his gesture to try and find the adequate language to denote the same process I’m calling para-semiosis. This process is what I think he’s reaching for when he says the paraontological. I just wouldn’t want to call it paraontological, I would want to call it precisely para-semiosis, or para-individuation; where, again, it is not the individual as the one, but the way in which the individual— we talked about it in terms of impersonation earlier—is in relationship to others who are being articulated; and their articulation exposes the conjunction of law and chance, as Du Bois would put it. I say, the conjunction of multiplicities of semiosis, or para-semiosis.

FM: So, when we seek to pay attention to the event of the Negro, or try to understand the way in which the event of the Negro is articulated, what we must seek out and what we are trying to pay attention to are Negroes-in-relation, or a-Negro-in-relation?

RAJ: I would put it somewhat differently. I wouldn’t say the event of the Negro. I said Du Bois was focused on the Negro as event. He’s very emphatic on using the term, “Negro,” and his emphasis is instructive. In his argument with Roland Barton about it, he’s actually arguing for multiplicity, that the term “Negro” designates multiple multiplicities. It’s a term that in its usage connotes multiplicities; and it connotes the historicity of multiplicities, and that’s why he wants to keep it. And so when I say that the immediate object of his concern is the Negro as event, I mean multiplicities as event. So one can say that Du Bois’ is really concerned with the event. Not the only event, but Negro as event, Negro as an instantiation of event, and in understanding the particularities of that instantiation, we begin to understand the situatedness and the eventfulness of thinking.

FM: And what do these particularities of instantiation look like? Where do we seek them out? How do we recognize them?

RAJ: This is where I agree with Du Bois, in the million life practices of those pressed into embodiment as Negro . . . that flesh which is disciplined and pressed into those bodies, which can purport this eventfulness in all of its historicity, what you would be calling “a Negro,” or in another sense, Negroes, or black. In being so disciplined to embody the event in this way, as Negro, that flesh manifests this eventfulness in its life practices and performances. And we can begin to look at specific discrete forms in dance, juba dance, or the Buzzard Lope dance— something I always talk about because I’m preoccupied with it a bit lately—and, as we talked about earlier, musical forms in which this enactment of eventful thinking is formally immanent. Not only formally but conceptually. I mean that those performing these activities have an expressed poetic knowledge, a technē poiētikē, wherein there is no hard distinction between fleshly performance and conceptualization of being-in-the-world. In other words, the performance articulates a conscious existential orientation. Take, for instance, the Buzzard Lope. Referring back to Bess Lomax Hawes’ 1960 film of the Georgia Sea Island Singers of Sapelo island performing the dance, in her interviews with them, they explain the choreography and what is the significance of what they’re doing in great detail; we would say, they’re theorizing it in a way that exhibits how they are cognizant of the event of the thinking.

FM: But what’s crucial, what is absolutely essential to this articulation, is the disciplining of flesh into discrete and separable bodies. It seems to me that what you were saying, and I’m trying to make sure I’ve got it straight, is that what’s absolutely essential, or what is a fundamental prerequisite for paying attention to this thinking, or this intellect in action, is a process through which flesh is disciplined. And by disciplined, I take that to mean also separated into individual bodies, which can, then, become an object of analysis and understanding and accounting at the same time that they can also becomes a condition for this other, anti-disciplinary articulation.

RAJ: And then it becomes an object. Yes, this is central to my thinking. Here I want to mark again a difference between me and Du Bois. For Du Bois, it is an unavoidable irreducible historical event and fact itself; which is the reason why he thinks the Negro is an important instance for understanding how humanity constitutes itself. He talks about this in “My Evolving Program,” where he says something to the effect, “that here we have human beings whose conditions of formation under tremendous violence are a matter of documented record. The juridical discourse is rich; the commercial discourse is rich. And what they’ve done under those circumstances, tells us something about how and what humans are.” This was behind his directing of the projected 100 year Atlanta Study project. When I talk about this in terms of the existential issue of the flesh being disciplined I’m paying very close attention to Spillers’ “Mama’s Baby and Papa’s Maybe” in this regard, because one of the things that I think needs to be attended to in that essay is that there is no moment in which flesh is not already entailed in some sort of semiosis, that it isn’t written upon or written into some order of signification. In other words, that flesh coming out of Africa is not a tabula rasa. There is no such thing as a homo sapiens tabula rasa. By definition, homo sapiens is that creature of semiosis, so it becomes then an issue of multiple orders of signification and semiosis in relationship to one another. And of course in the history of the constitution of the Negro, it becomes one of a putative hierarchy of semiosis and the conceit that it is possible to eradicate other semiosis in the favor of one. The fact that this flesh isn’t tabula rasa, it is always baring some hieroglyphic traces as it were, and we should not confuse those hieroglyphic traces, embodiment, with the flesh. So the flesh does not disappear. Here’s where I’m riffing on Spillers –flesh does not come before the body; flesh is always beside the semiosis. There’s a very particular statement from a 1938 WPA slave narrative that I find very useful, and that is Thomas Windham’s remark: “Us deserve our freedom because us is human flesh,” in which he’s articulating a conceptualization of a taxonomy of flesh, of humanity, in which fleshiness is not a substance underneath in which other things are written over, but it is an ineraseable constitutive element in the articulation of thinking, of being. Also inerasable—think of this in terms of a palimpsest— are all of the various ways in which there has been a writing with the flesh.

FM: When Windham says, “Us is human flesh,” is this “us” to which he refers, and this “human flesh” to which he refers, didivdual or individual? Or a better way to put it would be, is it separable from itself? In other words, is there discretion in and of the flesh before the imposition of body as a specific modality of semiosis?

RAJ: I’m not sure I understand your question, if I take it at its face value, either I’m suggesting or you’re construing me as positing the flesh as some sort of ideal substance. I thought I just said it’s not a tabula rasa.

FM: It doesn’t matter to me if it’s a tabula rasa or not, and I would agree that there’s no flesh independent of semiosis, but we’re talking about a specific semiosis, namely the specific semiosis that imposes upon flesh the discipline of body. The reason I‘m asking the question is because it struck me, though maybe I misunderstood, when you said that when we start to pay attention to whatever you want to call it, black poetic sociality, or intellect- in-action, there’s a specific process by which it comes into relief. And one aspect of that process, which I called crucial—but I’m happy for you to explain why “crucial” is not the right word—is a kind of disciplinary element in which flesh has imposed upon it body, in which flesh has body written onto it or over it. Can you say something more about that process?

RAJ: When I said “crucial,” I meant crucial for me and not crucial for Du Bois. And I was trying to mark how, for Du Bois, the constitution of the Negro is a historical fact; that here we have a population, to put it poorly, which has been stripped bare, and in that moment of being stripped bare, stripped of its own mythology, stripped of its own symbolic orders, is compelled to embody a whole other set of meanings, which it embodies. What they do in those given bodies is what he wants to focus on as showing what humans can do. I will take “crucial;” I say “crucial” because, for me, the intervention of modernity, the moment in 1662 in Virginia, or in the code of Barbados, or in the Code Noir—all of which expressly as juridical discourses define the Negro body—that is the superimposition of embodiment onto the flesh. Remember the Christian missionary-cum-ethnologist, Maurice Leenhardt’s conversation with the Canaque sculptor, Boesoou, on New Caledonia, where he suggests to Melanesian that Christianity’s gift to their thinking was the concept of the spirit. Boesoou has a retort, something like: “The spirit? Bah! You did not bring the spirit. We already knew the existence of the spirit. We were already proceeding according to the spirit. But what you did bring us was the body.” The spirit he refers to is not the Cartesian qua Christian esprit but the Canaque ko, which circumscribed, let’s say, by marvelous ancestral influx. Leenhardt, of course, misconstrues Boesoou’s retort as confirmation that the Canaque had created a new syncretic understanding of human being, combining the circumspection of ko with the epistemology of Cartesianism. The body becomes clearer as the physical delimitation of the person, who is identified with marvelous ancestral world, or as Leenhardt puts it,” the mythical world.” Roger Bastide will rehearse Leenhardt’s exegesis of Boesoou’s response some twenty-six years later and critique it as being no more than a scholastic reformulation of Aristotle’s notion of matter as the primary principle of individuation. Instead of an affirmation that the Canaque had assumed the Western concept of bodily delimited personhood, Bastide reads in Boessou’s retort affirmation of a continuing Canaque semiosis, in which personhood—personal identity, if you want—is not marked by the frontiers of the body. Rather, it’s dispersed at the cross-roads of multiple orders of referential signification, semiosis, which, I would say, are in relation to the flesh. In other words, there are multiplicities of hieroglyphics of the flesh, to use Spillers terms, indicating a divisible person akin to Du Bois’ “double-consciousness,” and which should not be confused with psychosis. So, for me it’s crucial, just as it is for Spillers, that “body” ‘belongs to a very specific symbolic order. We can track its genealogy in what we would call loosely the Judeo-Christian tradition, or if you want, Western Modernity; and by the time it gets to the 17th century it has a very specific articulation, which Michel Foucault and Sylvia Wynter have tried to trace for us. And so, yes, that moment is crucial because that moment is a beginning moment; not in terms of origin because, in that invention of body, in imposing it upon the flesh in this way, it does indeed reveal, highlight fleshliness, and the inerasibility of flesh, as well as the inevitability and inerasibility of acts of writing on the flesh. So that what Spillers calls “African forms” in “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe,” are semiosis that write the flesh, they don’t write the flesh in terms of body, but they still write the flesh and they don’t go away.

FM: Yes!

RAJ: Even though the moment of the Code Noir is meant to completely suppress them. As Barthes would say, whom Spillers is using in that essay, would somehow steal the symbolic significance from those other semiotic orders for its purpose. The fact of theft notwithstanding, it never quite does completely steal it away. And we know this. To talk about the specifics, when Lucy McKim, William Francis Allen. and Charles P. Ware begin to collect spirituals on the South Carolina Sea Islands during the Civil War, they’re writing in their notes and in their published pieces about how they hear rumors of these worldly songs, or the ways in which looking at those forms that the slaves are performing, there are recognizable Christian traces, structures and forms, but then there’s this other stuff that’s there they call “African,” and their slave informants called “worldly.” Those are indications of not only the continuation of the other semiosis that articulated relation to the flesh, but also a theorization of it in the fact that the informants are saying this is “worldly.” Those early collectors of spirituals borrowed from their informants this sense of, “oh, there are these worldly songs and these work songs that are doing this and that.” Beginning with McKim, who was the first one to actually try to notate the sonics of Negro-song, they all relate a certain “untranslatability” of these worldly forms. She says flat out that she can’t notate them. They are forms and structures and sounds that exceed the laws of musical notations. So we have these express references to the para-semiosis – and that’s why I call it para-semiosis – at work associated with the particularity of those populations called ‘Negro’, and that para-semiosis is brought into relief by the imposition of a body. Yes, it’s crucial, it’s an inaugural moment in the association of those human beings designated and constituted within the political economy of capitalist modernity as “Negro” and the poiēsis of blackness as para-semiosis. But I want to be clear, while the poiēsis of blackness has a particular association with the Negro, as para-semiosis, it is not just particular to the Negro. What is particular to the Negro with respect to para-semiosis is that the imposition of Negro embodiment brings into stark relief—and in a remarkably singular way—para-semiosis as species-activity. Para-semiosis does not begin with the Negro—demonstrably, it is prevalent among the Africans pressed into New World slave bodies, which is why Sidney Mintz called it “pan-Africanization.” I do not mean to suggest para-semiosis is uniquely African, whatever that term connotes, but it is, perhaps distinctively so. Distinctively African para-semiosis notwithstanding, I am in accord with Du Bois: in the very the forcefulness of Negro embodiment, the recognizable persistence of para-semiosis—call it what you may: syncretism, creolization, Africanism, of even poiesis of blackness—is indicative of a species-wide process. To say that poiēsis of blackness equates with pan-Africanization is to mark the historicity of the Negro as a specific embodiment of sentient flesh in space and time. That is to say, the specific situation that instantiates its poiēsis. Yet, insofar as that poiēsis is a function of para-semiosis, it’s a potentiality-of-being that might very-well attend other embodiments of flesh.

FM: It is part of the general history of the imposition of the body which is brought into relief at this moment as a function of our particularity.

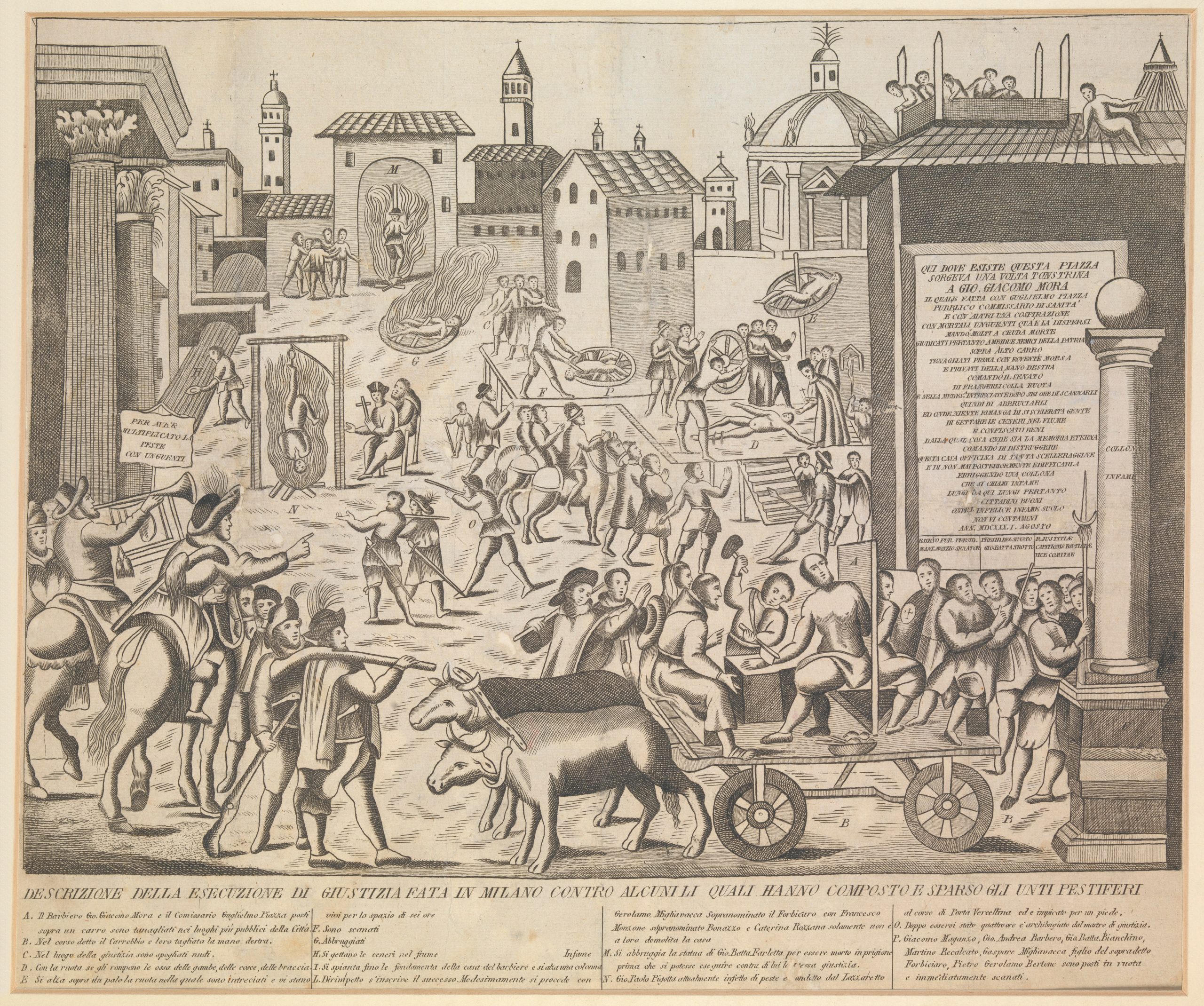

RAJ: And what interests me tremendously, and here I am now pushing beyond what Du Bois sets out to do, is the fact that those semiosis not only are continually articulated and become part of improvisation, but they are articulated in a way that is consciously about multiplicities, para-semiosis! So, there’s a way of thinking that attends to the event, that is eventful, that does not forget the event, that does not try to re-cast the event as origin, does not try to re-imagine the flesh as a pre-eventful origin to which one can be returned, and does not try to escape the event; but rather, because the imposition of the flesh necessitates a perpetual movement to escape the deadly effects of the body. One way that I talk about this in Sentient Flesh is in terms of the way in which the disciplining of the body is systematized, legalized, and is about what Derrida calls, the cannibalism inherent to capitalism. And there are numerous stories about the practices of consuming these Negro bodies, acts of torture where they’re consumed for the economy, but also acts of simple pleasure. There’s the story of Thomas Jefferson’s nephew by his sister Lucy, Lilburn Lewis, who butchered alive his seventeen-year-old slave, George, in the kitchen-cabin before all his other slaves by cutting off his limbs one by one, starting with the toes, pausing with each cut to give homily to the gathered slave. Returning home, to the Big-House, he then tells his wife, who has asked about the horrific screams she’d heard, that he had never enjoyed himself so well at a ball as he had enjoyed himself that evening.

FM: This is so interesting. It brings to mind a recent book that I’ve found very instructive, Edward Baptist’s The Half Has Never Been Told. I think what he’s very effective at showing how what he calls “second slavery” is an intensification of both the economic and erotic investment in the imposition, and then in the subsequent subdivision, of so-called black bodies.

RAJ: And the consumption of them! So the point I‘m making, then, is that precisely while they’re not trying to escape the event, they are in flight from the deadly consequences of embodiment, of the body being consumed. And being in flight, in movement, they continue to articulate eventful thinking. To try and anticipate the question you’re going to raise about specificity and concreteness, Frederick Douglass is upset with what he calls “Juba beating.” He’s scandalized by it because it serves the capitalist consumption of time and of consciousness and it’s barbaric. One of the interesting things about it is that the very thing he doesn’t like is part of what I’m calling “the flight from” that is not escaping the event of the superimposition of body upon flesh, but in fact marking the continuation of other semiosis that is foregrounding the eventfulness of being in the flesh, which is why I take Windham’s remark, “Us is human flesh,” as being very important. Because Juba is about beating the body. Think about it in terms of the story I just told you about Lilburn Lewis. Here we have – and there are many, many stories we know that—here we have a systematic structure that is about disciplining and consuming and torturing the body, beating the body in the service of either commercial consumption or . . . much of the torturing of the body is simply erotic. And with juba, the bodies that are being treated in this way— again the flesh that has been disciplined to be this body – here they’re beating the body, but they’re beating the body in accordance with another semiosis, that of producing rhythmic sounds for dance. And many of the juba lyrics parody the consumption structure of capital, so they are also resistant. In the performance, they are continuing the eventfulness of being in the flesh, and they’re working the flesh.

FM: They’re refusing, in a sense.

RAJ: And in working the flesh in that way, they’re showing that the flesh can be worked, can be written upon in a way that is other than the body.

FM: It is a refusal of the body, in a sense.

RAJ: They can’t refuse the body; which is why I call it para-individuation and para-semiosis.

FM: But I say a refusal of the body in full acknowledgement of the fact that when all is said and done, the body can’t be refused. It’s an ongoing process of refusal that does not produce or finish itself.

RAJ: I hear what you’re saying. I would agree with that. More than the refusal of the body, however, I want to emphasize the articulation of the eventfulness of writing flesh. The reason I want to emphasize this is because, to give a concrete example, when you listen to Peter Davis—who was one of the performers of the Buzzard Lope reported on by Lydia Parrish and subsequently recorded by both Alan Lomax and Bess Lomax Hawes—talk about what they’re doing with juba and what they’re doing with the Buzzard Lope, he’s presenting the aesthetics that they’re invested in, this is the act of poetic creativity, where they’re generating, transmitting and generating, a way of being.

FM: It’s an extension and renewal of a semiosis of the flesh.

RAJ: That is, again, an articulation of those semiosis already there when the semiosis of the body is superimposed on the flesh. Those semiosis have to be modified with the imposition of the body, they have to work with the body. I agree with you about refusal, but I’m wanting to emphasize what it is that they’re creating, that thinking, that eventful thinking; which is something not even more than refusal, but other than refusal. And, it’s in that otherness than refusal; which is my way of seeing in these particulars something of what Fanon talks about in terms of “doing something else.” In that other than refusal, there may—and here I’m again agreeing with Du Bois—there may be there signs of how humans can endure, if you will, capitalist modernity, and that’s why I draw analogies to what happens in Tunis, when the slogan, “Ash-sha‘ab yurīd isqāṭ an-niẓām” (The people want to bring down the regime), which paraphrases a hemistich from Chebbi’s 1933 poem, Itha a sha‘ab yumān arād al-hiyāh—commonly translated as “Will to Live,” but more literally rendered as “If the People One Day Will to Live”— functions as a way of articulating a certain kind of collectivity in relationship to juba and buzzard lope. They’re doing something very analogous to juba and Buzzard Lope.

FM: But the reason why it seems that refusal is an appropriate terms is based on my understanding of something you just said which is that what refusal does is both acknowledge the event of embodiment, while at the same time constituting itself as something like what maybe Derrida would call, after Nietzsche, an active forgetting of the event. Because, as you said, there’s no running away form that event that will have arrived, finally, at something else; there is no simple disavowal of that event, and if there is no simple disavowal of that event, then the event is acknowledged at the very moment, and all throughout the endless career of that refusal, which never coalesces into some kind of absolute overcoming. That’s why I was using the term, which, of course, doesn’t preclude your interest in and elucidation of something more or other than refusal. Maybe there’s always something other than or more than a refusal, though refusal is always there, as well.

RAJ: I’ll accept your account of refusal, and still insist on the particular emphasis I’m giving to the eventfulness of writing flesh. It’s interesting you mention Nietzsche, because in Sentient Flesh, I elaborate on the way in which Du Bois’ 1890 commencement speech critiques the Nietzschean concept and project. First, by paraphrasing Nietzsche very closely in its account of the Teutonic and problematizing the tension or the dyad, Teutonic/submissive, Teutonic/Negro. And then secondly, by foregrounding, at least in my reading of it, the imperative not to forget in the Nietzschean way. So I’m willing to say, yes it is refusing the body, but not forgetting the eventfulness of the imposition of the body, the perpetual imposition of the body, what Tony Bogues refers to as “continual trauma.” But, in that not forgetting, performs other possibilities of being, I’m wanting to avoid the therapeutic gesture of forgetfulness, which for Nietzsche, of course, has to do as well with a need of forgetting the foundational cruelty of man.

FM: There is something that I have thought about a lot, so I’m interested in whether you think this, too. It comes back to Spillers’ work and specifically “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe.” What you’re talking about alongside Spillers, you recognize it as something that is explicit in Spillers. But there is something about it that could be mistaken for implicit, which therefore makes it vulnerable to being forgotten. It’s this ongoing semiosis that I won’t say is before, or I won’t say precedes, but that shows up, let’s say, or comes into relief, in another semiosis, which is, in fact, this imposition of body. But so many of the readings of Spillers that have become prominent are readings that are really focused on what she talks about elsewhere in that essay under the rubric, “theft of body.” So I wonder if part of what made the reception of (Dis)forming the American Canon so difficult for Afro-American Studies, or for that particular formation in the academic institution, was that those studies had become so primarily focused on what Spillers refers to as the theft of body, which she associates with slavery. This emerges in another way, much later on, without any reference to or acknowledgment of Spillers’ prior formation of it, in the work of Ta-Nehisi Coates who also speaks of this theft of body.

RAJ: Yes, this has become a predominant and unfortunate misreading, in my view, of “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe.” It is explicit, remember she talks about captive and slave bodies. This is very careful phraseology on her part. She’s marking the movement in which the flesh becomes these bodies so that they can be captured. And so the focus becomes on that second move forgetting that no, no, no she’s giving us an account of how this body gets constituted, which is central to the whole piece. And then there’s her elaborate engagement with Barthes; she says she’s talking about Barthes’ theory of myth. And if you go and you read what Barthes has done there and what she’s doing with it, this is exactly what she’s focusing on, the semiosis of the body’s theft of the signification of the flesh, and then from that point on, this becomes the captive enslaved body.

FM: But there are just so many readings which are so focused on the theft of body, perhaps because “theft of body” is a resonant phrase that has no analogue that shows up in the text say as “imposition of body.” Perhaps the focus on “theft of body,” emerges from the way it resonates with another phrase, “reduction to flesh.”

RAJ: That reception of Spillers’ essay is less a reception in Black Studies than it becomes a reception in Feminist Studies in Critical Studies, and Sedgwick and Butler and many others who have their own critiques and investments in the problematic of the body, investments that are themselves circumscribed within the discourse of the body; so, they read Spillers accordingly. Nevertheless, Spillers’ is quite explicitly attending to the way the semiosis, the symbolic order of the myth of the body, in Barthian terms, steals the signification of the fleshly semiosis.

FM: I’m not trying to make the argument that it is not explicit in Spillers. I’m trying to make the argument that it does not manifest itself with regard to a phrase that is easily detachable from the rest of her argument, from the rest of the article. For some reason, the phrase, “theft of the body,” has been detached from the rest of that essay. And similarly, “reduction to flesh” has been detached from the rest of that article. And what I’m trying to suggest is that this tells us something not only about the reception of her essay in 1987, but the reception of your book in 1993. And I’m not talking about the (white) feminist reading or the women’s studies reading, I’m really specifically trying to zero in on something that happened in Afro-American Studies, including in its crucial and foundational feminist iterations. So when I think through the question of the fate of your first book, my hope for the renewal of a reading of it, is tied to my hope for the taking up, in a much more rigorous way, of the analytic of the flesh that Spillers is a part of, that obviously Du Bois is a part of, that you are a fundamental part of. That hope, with regard to a renewed engagement with Spillers, has been borne out in a lot of recent work. One thinks of Alexander Weheliye in particular, but there are many others. So, it makes me think a renewed engagement with (Dis)Forming the American Canon is sure to follow.