by Ross Posnock

I will begin with a brief passage from the contemporary American poet and essayist Douglas Crase’s 2004 memoir of the mid-20th century botanist/aesthetes Dwight Ripley and Rupert Barneby, who launched their pursuit of “plants in the North American desert” from what he—Crase—calls an “improbably sophisticated base.”

The baroque furnishings of Rupert’s loft, the Surrealist paintings, the books in too many languages and especially those in English—not so much Auden and Isherwood, but Firbank and Corvo, the three Sitwells, the whole privileged cohort of Harold Acton, Evelyn Waugh, Nancy Mitford, Henry Green and Anthony Powell—put me on guard. Prominent on one shelf was Memoirs of an Aesthete, perhaps the best known of Harold Acton’s titles, which in those days stood out to me mainly for the awkward rhyme it cast from aesthete to effete, and which practically advertised that here was a library written by and for the frivolous, the highbrow, the undemocratic, and the epicene (2004: 23, 90).

Though his unease speaks for itself, Crase also voices familiar American anxieties that “sophistication” triggers. Saddled with the scent of British decadence, “sophistication” has never entered the literary critical lexicon. Indeed it has never been a contender, and now less so than ever given the furious political rage against elites. But the word merits reexamination in discussing an author of whom it was said (notoriously, by Norman Mailer) that “even the best of his paragraphs are sprayed with perfume,” (1992: 471) of whom, at his funeral, “his aestheticism and ultra-sophistication” were noted, on the way to a concession that “Jimmy was a civil rights leader” too. The speaker, Amiri Baraka, did not dwell on “sophistication” but implicitly set it against the political—a predictable binary that James Baldwin did not endorse (1991: 453).

In an event that begs to be read as an allegory of Baldwinian sophistication receiving its public due—in England, appropriately enough–in 1965 he debates at the Cambridge Union William F. Buckley, that veritable caricature of American patrician capital S “Sophistication”—he of the silkily disdainful ornate vocabulary and orotund cadences. Easily available on You Tube, the debate shows Baldwin not only triumphing, but producing in Buckley the grimaces and sneers and other facial contortions that signal the latter’s unhappy consciousness that suddenly he does not own aristocratic poise and British intonation, that a usurper, an upstart, is in his midst, an unaccountable mocking black double replete with Oxonian intonation. At one point Buckley snidely comments on this—“in The Fire Next Time he speaks without a British accent which he used for you tonight”–evidently unnerved that what he assumed was his own vocal signature is not his alone. As if Baldwin has “stolen” his voice!

What we might call the “setting”—the frame—of Baldwin’s sophistication is a fluid ease of movement, inevitably arousing controversy, between countries and classes and realms—the impoverished young expat improvising a life all over Paris, the apocalyptic voice of the civil rights movement, the famous author comfortably making his way in the wealthy celebrity world of global literary stardom, the gracious host at his final home in the village of St Paul de Vence in the South of France, all the while keeping the Harlem hometown “street” credibility and charisma that even Baraka admitted he never lost. What Baldwin once wrote of Duke Ellington—that he was “able to move, without missing a beat or manifesting the slightest uneasiness, from Harlem cornbread to Buckingham Palace caviar and back again, ad infinitum–” describes the ease of his own interracial and class movements (1998: 673). This mobility of Baldwin’s is usually called “cosmopolitanism,” a word suggested by Baraka’s “ultra-sophistication”; but the latter does not reduce to the former. Whereas “cosmopolitan” is abstract, keeps us at a distance, is necessarily a political statement about one’s relation to nation, “sophistication” may be or become political but is first a mode of physically being in the world, the texture and surface displayed in clothes, carriage, voice, gesture: in presence, in sum.

But the presence of sophistication troubles our deeply American fantasy of transparent identity: “she would be what she appeared and she would appear what she was,” as that lover of sincerity the young Isabel Archer describes herself (1995: 56). Behind Isabel’s ideal is an intellectual genealogy worth sketching here, even roughly, for it is decisive in shaping the status of American sophistication as an oxymoron. I call her fantasy deeply American but its romantic individualism recalls Jean Jacques Rousseau’s declaration early in the First Discourse (1750): “how pleasant it would be to live among us if exterior appearance were always a reflection of the heart’s disposition.” Society, however, spoils the chance for such immediacy, for our “much vaunted urbanity” requires we don “false veil of politeness,” demands the suggestion of a manner and a style—often found in the “richness of attire” and “elegance” of a “man of taste” (1964: 37). Rousseau would have us cast all this off. He draws out the class implications in his Confessions: “Among the people…natural feeling makes itself heard,” whereas in the “highest ranks of all it is absolutely stifled, and beneath a mask of feeling it is always self-interest or vanity that speaks” (1953: 144). To minimize vanity he recommends wearing the “clothes of a farmer,” an outfit shorn of “ornamentation”-–the enemy of “virtue, which is the strength and vigor of the soul. The good man is an athlete who likes to compete in the nude” (1964: 37-38). To the “vile ornaments” that help comprise “urbanity” Rousseau opposes the rustic “virtue” of nakedness. Although romanticism, esteeming the feeling heart’s urgent expression, is conventionally opposed to another foundational American logic, Puritanism, with its root suspicion of untrammeled subjectivity, in this context both share an anti-materialist, debunking asceticism, as if impatient “to wipe away the rubble of culture and get to the bottom of things” (to borrow Adorno’s words about another foe of “mediating functions” Thorstein Veblen) (1981: 84, 91). One way to explain this convergence is that Rousseau, born in Geneva, the laboratory of John Calvin, inevitably felt this shaping influence, especially in his early writings. The First Discourse is animated by a skepticism not only of “the rubble of culture” but also of “this herd called society”—as if to acknowledge the primacy of social bonds—indeed relationality itself–represents a fall into inauthenticity (Rousseau 38). In other words, it is difficult to resist naming Rousseauism, inadvertently acting in concert with Puritanism, as a crucial tool in the conceptual arraignment of sophistication as un-American.

The Confessions is the autobiography of a flagrant anti-sophisticate, thereby affirming its author’s self-description as a paragon of sincerity and honesty. He copiously illustrates his farcical romantic adventures and the ineptitude of his social performances– his appearance of slow-wittedness and “stupidity” made conversation a particular torture in the drawing rooms of Paris. Rousseau also reveals himself as an adept shape-shifter and impostor when the occasion required. But the Rousseau who helped shape mythic American self-identity is not a man of contradictions–staging his anti-theatricality, his sly stupidity. This Rousseau was put aside for the flattened opposite—champion of the natural as the ground of virtuous being. “Ground” here is not only figurative but literal. For the vastness of American land—the “spirit of place”—(as D.H. Lawrence put it and Charles Olson on Melville would reaffirm) facilitates visceral assent to the US as Nature’s Nation (a title of a book by Perry Miller, who attributed the phrase to Emerson). Scott Fitzgerald rehearses this recognition scene in one of American literature’s canonical moments, the end of The Great Gatsby (1925) where the eyes of the Dutch sailors’ watch in awed wonder the “fresh, green breast of the new world.” But the moment is “transitory, enchanted.” No sooner has Fitzgerald evoked this Eden then he has the trees “pandering” in whispers, trees soon to vanish into lumber for building mansions. Two years before Gatsby Lawrence had been jeeringly contemptuous: “The land of the free! This, the land of the free! Why, if I say anything that displeases them, the free mob will lynch me, and that’s my freedom.” In no other country, says Lawrence, does the individual have such “abject fear of his fellow countrymen.” The fear undergirds the “myth of the essential white America,” which, he famously concludes, rests on “the essential American soul”: “hard, cold, stoic, isolate and a killer. It has never yet melted” (1977: 9, 68).

But the unflattering exposure by literary men of what the American rhetoric of mythic nature and natural man conceals had no chance to prevail against the perennially potent spell cast the previous century by geographical sublimity and the “manifest destiny” it was held to embody. This phrase (of 1845) had caught the spirit of an ambition to colonize nature expansively under the auspices of a romantic nationalism that had started with Thomas Jefferson, great admirer of Rousseau. The success of that geographical effort was more than matched by the ideological colonization of Nature, turning it into America’s birthright, a crucial fantasy in building our massive bias towards triumphalism and self-congratulation. These dispositions, seemingly benign, are actually anxious defenses fueled by hostility to various forms of New World otherness—be they “savages,” witches, antinomians, African–Americans and indigent Europeans, many of the latter conscripted to indentured servitude. They all trigger the reflex branding–“unnatural.” While Rousseau, himself a commoner and insistent outsider on many levels, did not intend this discriminatory effect, his purism tends to function this way, given his commitment to transparency’s absolute value even as a doomed project, a fixation that Jean Starobinski explored half a century ago. As disseminated in the new Eden, seeds of Rousseauvian purism cultivate a host of durable and pernicious dichotomies, all keeping our native anti-intellectualism and its attendant pathologies flourishing, including abiding suspicion of the urban and urbanity in general, and pious veneration of the simple life.

The motor of that suspicion is an unspoken assumption that to possess or compose a manner or style opens up a psychic split or gap fatal to the self-identity that is the basis of sincerity. “One no longer dares to appear as he is,” laments Rousseau (1964, 38). He calls that fatal gap “reflection” and eventually regards it “the root of all evil,” the enemy of the immediacy of first impulses; with reflection comes our exile from the natural world ruled by instinct (Starobinski, 1988: 207). Perhaps this fall into the reflective mediacy of manner or self-fashioning still retains residues of guilt in the sophisticated, manifested in the fact that sophistication is difficult to talk about. Save for Daisy Buchannan in The Great Gatsby, one feels uncomfortable proclaiming one’s sophistication, it sounds…unsophisticated, as if the ban on talking about one’s sophistication obeys the logic of sincerity’s pre-reflective transparency. A hint of defensiveness, of anxiety–suggesting sincerity’s priority–attaches to our relation to sophistication. This hints at an abiding tension between sophistication and self-consciousness, a tension with a long history in aesthetic/cultural theory. We will look at some of this history below while also noting late in the essay that, like Rousseau, Baldwin too elects nakedness as a desirable state of being, yet he does so without warring against urbanity. Indeed urbanity is enabling for Baldwin. 200 years after Rousseau, in the freedom of Paris, the city the philosopher enjoyed only against his will, regarding it as the mecca of phoniness, Baldwin finds the opportunity to fall in love, daring to make real what terrifies Jim Crow America: the ideal of colorblind intimacy. What he learns is that “people do not fall in love according to their color”: nakedness “has no color” (1998: 366). Fusing what Rousseau sets in conflict—the urbane and romantic–Baldwin is spared the neurosis inherent in Rousseauvian mystique. Of one its products, 1950s Beat romantic primitivism, Baldwin had this to say about what he called its “mystique”: “No one is more dangerous than he who imagines himself pure in heart: for his purity, by definition, is unassailable” (1998: 277).

Baldwin’s timeliness seems to be ratified on a daily basis, but the best known evidence, in addition to academic conferences, books, and a journal now devoted to him, are Raoul Peck’s acclaimed film I Am Not Your Negro (2017) and novelist Jesmyn Ward’s The Fire This Time (2016), her edited collection of essays by young black writers musing upon and updating Baldwin’s apocalyptic warnings of 1963. And there is the rise to international prominence of bestselling essayist and memoirist Ta-Nehisi Coates as a media darling, the writer Toni Morrison proclaimed “heir” to Baldwin as America’s “conscience.” Yet their differences are more striking than similarities: with his carefully managed self-image as a man of virtuous organic solidarity, Coates seems almost the “anti-sophisticate” compared to the expatriate, hedonistic cosmopolitan he venerates. Another dissonance: Raul Peck’s film is full of stirring clips of Baldwin’s public presence but gives little hint of his unsettling skepticism about what we ordinarily mean by race and identity. So for all his ubiquity Baldwin is still out of focus for us. Imagine the dilemma of earlier commentators grappling with his recalcitrance to familiar categories. The culture had to devise ways to “package” Baldwin.

Ebony gave it a shot in a cautiously admiring 1961 article titled “the angriest young man.” Baldwin granted his anger but distinguished it from bitterness. “I could be described as bitter if I hated white people, which I don’t.” He tells Ebony-–prime arbiter of black bourgeoisie taste and standards; “Why Negroes Don’t Like Eartha Kitt” appeared in a 1954 issue—he tells them “with a smile, ‘I am what you might call a drinking man although I don’t start the day with a shot of scotch.’” This is because he is sleeping in the morning, since his writing time commences after midnight. “He has few close friends but a wide circle of acquaintances, mostly in the arts.” Ebony leaves it at that. Maintenance of Black Dignity is their raison d’etre. “Angriest” and “slim, sardonic, pleasure loving” bachelor will have to suffice; beneath this language beckon matters best left unmentioned (Morrison, 1961: 23-30).

This reticence makes a good deal of sense in 1961 and is an unintended tribute to Baldwin’s inassimilable being. Sophistication’s constitutive oddness suits Baldwin because his self-fashioning was unprecedented and unprecedentedly odd: a high school graduate from Harlem, who never attended college, small in stature, with frog-eyes, as his step-father had often told him, whose speaking voice sounded like that of the British actor Leslie Howard (to borrow Darryl Pinckney’s remark), whose homosexuality was an open secret (he regarded the word as descriptive of acts, not identity), whose essayistic voice sounded unraced, whose prose style was the envy of the New York intellectuals in whose journals he would precociously publish. Of his intricate syntax and elaborate, exalted cadences, F.W. Dupee remarked in the inaugural review of the inaugural issue of the New York Review of Books: “Nobody in democratic America writes sentences like this anymore. It suggests the ideal prose of an ideal literary community, some aristocratic France of one’s dreams” (1963: 2). “Aristocrat” was in fact a word Baldwin employed; as we will see near this essay’s conclusion, he stripped it of its usual sense of entitlement, rewriting it as a synonym for a certain kind of calm, unflappable public action.

Baldwin’s conspicuous artifice suggests that he understood identity as did his revered Henry James—as precisely unnatural, not a given determined by biology or social class but rather as “the way in which one puts oneself together…an invented reality” comprised of a “great number of elements” (2011:89). This may be the cornerstone of his sophistication. He assembled himself with no small measure of audacity, in the process shattering received expectations of blackness, of masculinity, of intellectuality, of sophistication. If forced to find a single word to sum up the assemblage named James Baldwin it might be “freak,” a word he used in 1972 to describe himself (1998: 363). “Sophisticated freak” if forced to find two words.

Baldwin’s poise, as the video of the Cambridge debate with Buckley shows, made him a natural for television, a medium he would master early as a key technology in his rise to celebrity. He shares a comparable level of televisual mastery with the country’s most famous sophisticate circa 1960—the new young President. Indeed Edmund Wilson had made the comparison. Of Baldwin in late 1962, Wilson notes in his diary: “We heard him give a lecture at Brandeis. … He seems to have taken over some of President Kennedy’s manner at his press conferences, leaning forward, listening intently & seriously, answering right away and without hesitation…in such a way as to be sure he has the sympathy of his listener” (1993: 168-169). Baldwin’s poise in public is powerful because it is in the service of his intellectual dexterity: it allows him calmly, carefully–and at the same time passionately–to make arguments, demanding that his audience listen to his terms, his logic, his critique, never using sentimentality or other glib tactics to win people over. (Sentimentality, he says, is always an “aversion to experience”). He never flatters; or wants to be loved. “’Elegant’ was the word that Mary McCarthy kept coming back to in connection with Baldwin, in her 1989 memorial tribute. From our vantage, three decades after his death, Baldwin’s elegance is founded on a certain measure of impersonality, an immunity to our culture of hype and ingratiation which makes him seem from another time, a lost world.

Here I want to pause: I will return to Baldwin after taking a wider, longer view to dilate upon some of the points raised above about the peculiarities of “sophistication.”

This is how the ‘sophisticated’ talk about sophistication: they don’t. When the topic comes up one meets blankness, disavowal, dismissal, or a request to change the subject. So when the former editor of The New Yorker magazine, author of books on ballet and on Sarah Bernhardt, and head of the esteemed publishing firm Alfred Knopf, Robert Gottlieb, was asked about sophistication he dismissed it, had nothing to say about it. The most he would concede of a famously sophisticated personage and a good friend of his—Irene Mayer Selznick—was that she was “classy. “ When his interlocutor presented him with Kenneth Tynan’s verdict—that American sophistication is an oxymoron– he agreed. Sophistication is Noel Coward, Gottlieb added, a British thing. In a 1971 diary entry Kenneth Tynan, the English bon vivant, drama critic and essayist wrote:

American talent does not survive sophistication. It needs to preserve a certain naivete, a hayseed element, even a touch of the child, and the primitive, if it is to retain its juice & energy. This is true of Huckleberry Finn, of Scott Fitzgerald (always an outsider in Paris & the Cote D’Azur), of Hemingway (with the boyish braggarty of his virility cult), of the out-of-towners who founded and wrote for The New Yorker, [Harold Ross et al], of Ring Lardner’s ingrained & obsessive provincialisms, of Whitman, Sherwood Anderson, Runyon, John Ford…When urban sophistication lays its hands on the American artist, it is like frost on a bud…. When US talent goes elegant, NY really becomes…a ‘road-company Europe’. Exception: Cole Porter is about the only one I can think of” (2002: 74)

One might read this hymn to the hayseed sophisticate as Tynan’s rendition of the effects of American anti-intellectualism, our chronic condition that seems hard to separate from a consideration of American sophistication. When we ponder why in America sophistication is “frost on the bud” the most obvious suspect is our native Puritanism. Its unease with and suspicion of art—indeed with subjectivity itself—encouraged a “plain style” that by the late 19th century turned into the reign of literary “realism,” a genre that minimized artifice and maximized fidelity to facts (especially those that confirmed bourgeois verities). H.L. Mencken, the most influential critic of the 1920s, made “the Puritan” his all-purpose epithet to describe American culture’s obedience to “Boston notions of English notions of what is nice” (1987: 6). Though no Puritan, Emerson shares their impatience with novels and in “Art” says that the actual art object has a certain “paltriness” compared to living human expression: “the sweetest music is not in the oratorio, but in the human voice.” “Reality hunger” is still said to be our insatiable craving, one that distrusts the power of imagination. Whereas sophistication, starting with its etymology, points in the opposite direction: The OED reports: as verb: sophisticate: “to mix with some foreign or inferior substance,” “to render impure,“ “to render artificial, to deprive of simplicity, in respect of manners or ideas”) as noun: sophistication: “the use or employment of sophistry…falsification; disingenuous alteration or perversion of something; conversion into some less genuine form.” Only by 1850 appears “the quality or fact of being sophisticated; especially (a) worldly wisdom or experience; subtlety, discrimination, refinement; (b) knowledge, expertise, in some technical subject.” The OED lists not a single “‘positive’ definition of the term sophistication…It is not so much that the meaning of the term shifts from negative to positive as that the negative meaning persists within the positive, with the result that even the most celebratory invocations of sophistication as worldliness remain haunted by the guilty sense of sophistication as a deviation from, even a crime against, nature,” as Joseph Litvak observes in his excellent Strange Gourmets: Sophistication, Theory, and the Novel (1997: 4).

All this baggage, etymological and otherwise, burdens sophistication’s life in Nature’s Nation: our homegrown art forms–plain style and literary “realism”–are anxious anti-art art forms that make “sophistication” a target to shoot against: decadent affectation and exhibitionism but also a symptom of undemocratic (East coast) elitism. Bashing it will always be a sure fire political applause line. From this soil grew the suspicions that have, for instance, long shadowed Henry James. “ ‘Art’ in our Protestant communities” is still regarded as “vaguely injurious,” James wrote in 1884, as he was beginning to break with canons of realism and to ignore strictures of Victorian moralizing (1984: 47).

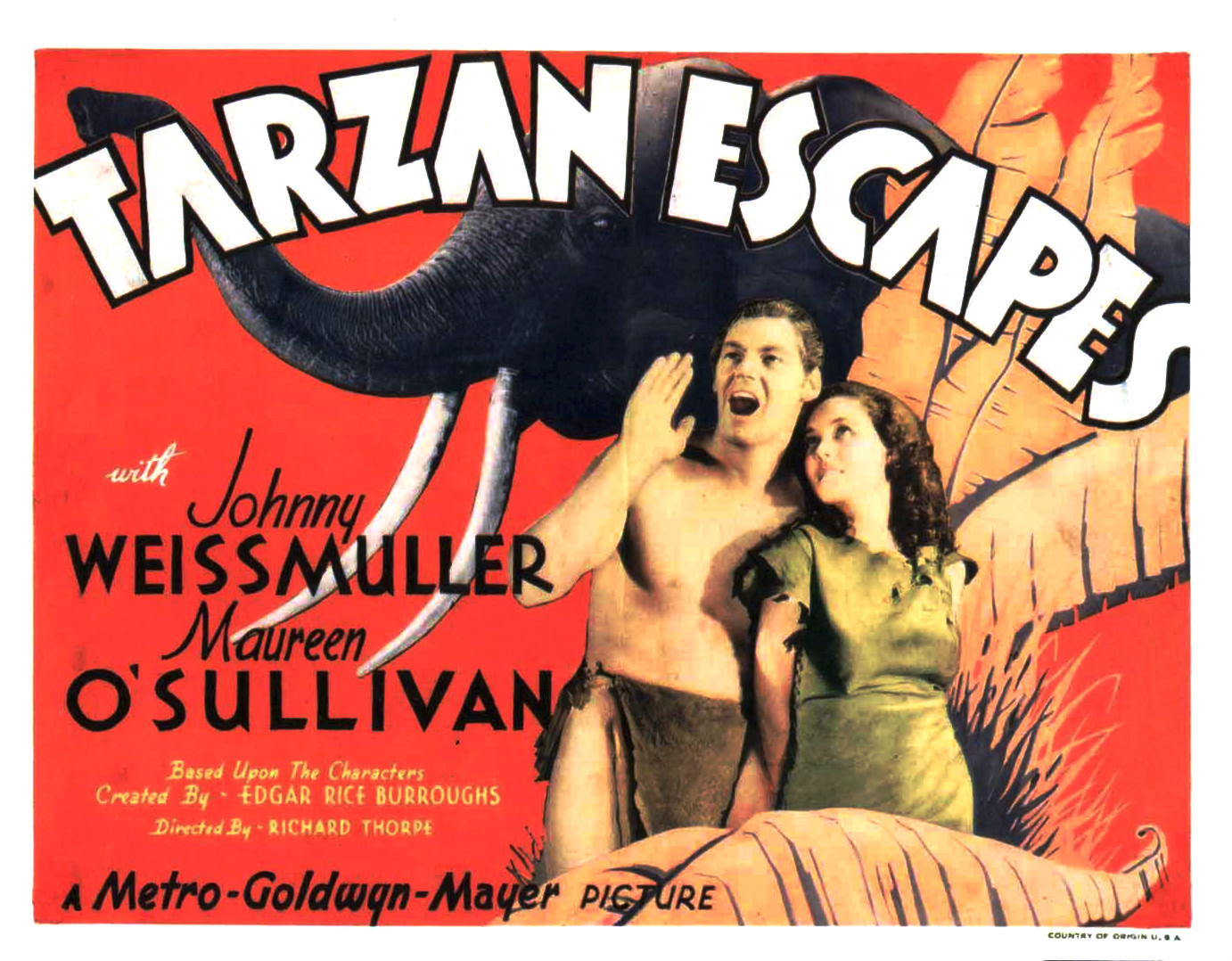

But if our Puritan induced national unease with art and artfulness encourages looking askance at sophistication, our other pillar, capitalism, champions it as a motor of cultural commodity acquisitiveness. The “culture philistine,” a phrase made famous, if not invented by, Nietzsche, is one who confuses self-cultivation with culture and depends on being in the know, keeping up with the latest. Every product—from cars to university press books to haute couture and cuisine–depends on advertising exhibiting this year’s version of sophistication to instigate the envy and anxiety that creates desire, otherwise the market would grind to a halt. The 1950s were a boom-time for sophistication; two new technologies–the paperback revolution, the LP record–made high culture goods unprecedentedly available to an aspiring middle class. New performers emerged—late night radio hosts, stand up comedians and cartoonists purveying “sick” humor and political satire (Jules Feiffer, Mort Sahl, Lenny Bruce), beatnik poets and black jazz musicians in Village clubs. And that witty parody and embodiment of sophistication as predatory worldliness: Eartha Kitt. They were all part of a thirst for urban and urbane extremity to cut against the torpor of “the tranquilized fifties” (Robert Lowell’s phrase), a rage that Mailer caught in The White Negro, itself a manifesto for a new hipster lexicon of sophistication. While denying it to black people: “the Negro, all exceptions admitted, could rarely afford the sophisticated inhibitions of civilization, and so he kept for his survival the art of the primitive” (1992: 341).

Without using the Nietzschean term, Baldwin comments on the “culture philistine” in a 1959 essay on mass culture. “The aim of the people who rise to a high cultural level—who rise, that is, into the middle class—is precisely comfort for the body and the mind.” But the modernist books and records they consume are bent not on comfort but on “disturbing the peace—which is still the only method by which the mind can be improved.” These culture goods tended to be sold and purchased as markers of status, they “bear witness… to the attainment of a certain level of economic stability and a certain thin measure of sophistication. But art and ideas come out of the passion and torment of experience: it is impossible to have a real relationship to the first if one’s aim is to be protected from the second” (2011: 4). Here “thin” “sophistication” functions as a species of protection, on a par with white American “innocence,” a key target in The Fire Next Time. Ironically, in 1964 Baldwin would be accused of trafficking in “thin” sophistication—called a “show-biz moralist” “given over to fame and ambition,” betraying a “once courageous and beautiful dissent” (Brustein, 1964). All because he refused to know his place (as our black moral conscience) and collaborated with fashion photographer Richard Avedon, his high school friend, on an expensive coffee table book that brought together Avedon’s photographs of American celebrities and anonymous mental patients, with Baldwin’s essay “Nothing Personal.” This critique would hardly be the last nagging effort to hold the high living Baldwin to ascetic standards.

How, in the US, does sophistication “thicken” to become something other than bourgeois insulation or the antithesis to passionate experience, something other than self-conscious manner, pretension or snobbery? The answer is obvious: it must become natural, to invoke that All-American panacea. Thomas Jefferson posited a “natural aristocracy among men” grounded in “virtue and talent,” to replace “an artificial aristocracy founded on wealth and birth, without either virtue or talents”; analogously, one could speak of a “natural” sophistication manifested in ease of embodiment, a nonchalance enacted in deed and air and bearing (1988: 388). Hence the “sophisticated” don’t talk about sophistication; they are busy being sophisticated. But Jefferson’s upholding of the “natural” couldn’t predict that the word and idea would become an American fetish, an impoverishing ideology promoting, as noted earlier, an array of evils, among them racialist thinking as well as anti-intellectualism and ahistoricism. Within the social and cultural environment in which American sophistication is performed the ideology of the natural rules, fomenting hostility and suspicion, external and internalized, inevitably deforming those performances. Think of the founding editor of The New Yorker, the aggressively philistine Harold Ross, (whom Dorothy Parker called a “monolith of unsophistication”); or Mencken, national arbiter of sophistication who couldn’t bear New York, preferring his native Baltimore, where he lived with his mother; or Sinclair Lewis, often playing in public the role of a bumptious bounder in the style of his George F. Babbitt: these are three of the 1920s “martyrs” of American sophistication.

When we leave the US we discover that the natural and sophistication remain linked, but dialectically rather than antithetically. I am thinking of Italian Renaissance authors in the 16th century instructing aspiring courtiers to conceal the artifice of manner behind apparent simplicity. To do so was to practice sprezzatura–a word coined by Castiglione in The Book of the Courtier (1528)–his neologism designed to instruct those at court “to conceal all art and make whatever is done or said appear to be without effort and almost without any thought about it…Much grace comes of this…. Art, or any intent effort, if it is disclosed, deprives everything of grace” (2002: 32). Castiglione’s dialogues recommended “that cool disinvoltura”–ease—“of those who seem in words, in laughter, in posture not to care” (33).

Unlike the US fetish of the natural, which claims it as a veritable birthright, the Italian and French theorists of taste and deportment and art do not simply celebrate the natural but turn it inside out, preserving the natural by denaturalizing it, as the making of a manner becomes the appearance of the spontaneous. So compelling to readers was this crafting of an artless art, (itself subject to all sorts of deceit, since lack of affectation can itself be affected, a perennial possibility The Book of the Courtier discusses) so compelling did readers find it that they tended to ignore Castiglione’s elite court context: the book was “mistaken” by many as ”a practical handbook of manners” (Javitch, 2002: vii). Dr Johnson in the late eighteenth century praised it as the “best book that was ever written on good breeding” (qtd. Burke, 1995: 390). The dandy Beau Brummell tacitly states its logic: “If John Bull turns around to look at you, you are not well dressed; but either too stiff, too tight, or too fashionable” (qtd. Kelly, 2006: 5). The reclusive genius, poet and essayist Giacomo Leopardi, reprises the paradoxes of sprezzatura in his vast notebook Zibaldone, (composed in 1817-1832) in the course of a critique of Romanticism’s effort directly to recover the primitive. Regarding creating the impression of naturalness and spontaneity, “which ought to appear achieved with supreme lack of effort,” without “any show of artifice and arduousness,” Leopardi says that in fact such impressions “are the daughters of art alone, those which cannot be achieved except through study…are most difficult to get the habit of, the last to be achieved, and of such a kind that even having acquired the habit, it is impossible to put into practice without extreme exertion” (2015: 1258, # 3048).

Sprezzatura is etymologically connected to heedlessness—of art, of danger, of ostentation—which is less a complacent neglect or ignoring than a masterful ease, a refusal to let anxiety enter, as Paolo D’Angelo has recently observed in his book on artem celare (art concealing art). French classical thinkers, like Bouhours in the 17th century, were concerned with cognate concepts that similarly resist transparent definition– concepts such as delicacy and grace. They define themselves as a “Je ne sais quoi.” This phrase—“I don’t know what”—names a refusal to name and thereby make self-conscious and subject to preordained fixed rules behavior that eludes cognitive clarity, that instead relies on the charm of surprise. Readers of Bourdieu’s Distinction will recall that it draws on the great seventeenth-century French debates over taste between the learned academics—seeking to ground art in rules–and the mondain—aristocrats “who refused to be bound by precept, made their pleasure their guide, and pursued the infinitesimal nuances which make up ‘je ne sais quoi,’” debates that Bourdieu calls “a permanent struggle” appearing in every age (1984: 70). Like the growing new field of aesthetics, sophistication flew under the radar of rationalism or intellectual judgment, with their appeal to objective criteria, measures, proportions (D’Angelo, 2018: 121). “Nothing is liked more in nature than what is liked without knowing precisely why,” noted Father Bouhours of the delicacy of grace (qtd. D’Angelo 122). “Urbanity”—derived from urbanitas, the Roman ideal of refinement–is used in 1644 as “a scarcely perceptible impression… it can be felt but not seen… It is the science of conversation” (Barnouw, 1993: 57). Eluding rules and language, these new concepts rely on nuances of social interaction, a subtlety palpable and felt, understood but only intuitively, attuned to the unique flow of interaction.

This demotion of language and of rational cognition orients the new aesthetic perspective on sensibility in the late 17th century. Christoph Menke in his book Force: A Fundamental Concept of Aesthetic Anthropology notes that Leibniz distinguishes between rational and sensible cognition; the rational is based on definitions and the sensible is based on examples, and of the latter we must say that they are ‘Je ne sais quoi’: in other words, “I know something even though I do not know it with the precision of a definition” (2012: 15). Adds Menke: “by distinguishing between the ability to know and the ability to define, Leibniz transforms the domain of the senses into an object that is open to epistemological inquiry: the object of ‘aesthetics’” (15). Leibniz, Menke notes, supports his claim that we have reasons in the form of examples—embodiments–rather than definitions for our “sensible cognitions” by appealing to the practice of painters and other artists. They have the ability to judge correctly whether something has been done badly or well but are “unable to give a reason for their judgment.” Of work they dislike, all they tend to say is –“’it lacks something, I know not what.’” Artists’ responses show that “sensible perceptions and judgments can be called ‘correct’ without being clear and distinct and, thus, without our defining the criteria by which the perceptions and judgments are being made” (16). The phrase “clear and distinct” nods to Descartes’ criterion for knowledge and signals Leibniz’s liberation from it, via his respect for artists’ intuitive knowledge.

It seems we have gone far afield from Baldwin. But have we? Consider his statement from 1959:

“What the times demand, and in an unprecedented fashion,” Baldwin says, “is that one be—not seem—outrageous, independent, anarchical. That one be thoroughly disciplined—as a means of being spontaneous” (2011: 9). The first part of this exhortation is couched in the rhetoric of authenticity impatient with appearance (“be–not seem”). But Baldwin complicates this Isabel Archer stance by insisting that discipline—self-conscious control–releases the spontaneity of outrage and anarchy. In effect he is preserving the natural by denaturalizing it, to repeat the logic of sophistication’s constitutive paradox, its artless artfulness. Baldwin’s grasp of sophistication’s logic is mediated at least in part by Henry James, who taught him that being an American is a “complex fate,” the quotation Baldwin uses to launch the opening essay of Nobody Knows My Name. (The Portrait of a Lady and The Ambassadors were Baldwin’s two favorite James novels, ones he taught during his teaching stints and also wrote about. In 1968 when asked what book he would recommend to a Black Power militant he replied The Princess Casamassima) (Leeming 1994: 300). Fascinating James from the start is how American spectacles of naturalness or innocence also depend on what he calls “the pervasive mystery of style”: at the heart of “Daisy Miller,” for instance, is the mystifying question of just how sophisticated is the heroine’s naivete, how cunning her social affronts– this young woman from Schenectady is enjoying herself in Rome.

My basic claim in what follows is that the word and concept “sophistication” is crucial if we would appreciate Baldwin’s intricate performance in “The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy,” his self-described “love letter” to Norman Mailer (that first appeared in Esquire, May 1961). In its depiction of the relation of a black to white writer, the essay is nothing less than unprecedented and its audacity merits the admittedly vexed angle of vision that “sophistication” affords.

In “The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy” Baldwin’s shattering of expectations starts with the second sentence when he casually remarks that his essay is a “love letter.” First of all, what in the world is Baldwin doing writing a “love letter” to Mailer, author, four years earlier, of the often outrageous racial primitivism of The White Negro? Baldwin should be coming out with both guns blazing. “Love letter” disconcerts, to put it mildly. In 1961 it would carry more than a whiff of transgressive shock with its hint of interracial homosexual relations. In an interview after the Baldwin essay came out, Mailer said: “he had me strong where I wasn’t strong and weak where I wasn’t weak.” Rachel Cohen reads this as evidence that Mailer was “upset” by Baldwin’s phrase “love letter” and “would have preferred to have been praised for his violence than for his tenderness, or that he was uncomfortable with the idea that Baldwin was a little in love with him or the implication that he might be a little in love with Baldwin” (2004: 239). These then scandalous implications may partly be why the phrase “love letter” is usually ignored and the essay is best known for Baldwin’s contempt for hipsters and beats. The “downright impenetrable” nonsense he finds in “The White Negro”—Mailer relies on “borrowed heirlooms” of white male sexual fantasy “so antique” that Baldwin is shocked that “at this late hour” they should be “stepping off the A train”—is dismaying, but what is more, Baldwin is “baffled by the passion with which Norman appeared to be imitating so many people inferior to himself, i.e. Kerouac and all the other Suzuki rhythm boys.” What is Mailer, whose best work is subtle and complex and tough, “doing, slumming so outrageously, in such a dreary crowd?” (1998: 277).

The opening of “The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy” presents a not so innocent abroad: Baldwin recollects enjoying himself in a Paris living room the evening he first met Mailer. Though the enjoyment is mixed with wariness, for the bristling Baldwin (“I was extremely worried about my career”, i.e. “fighting for my life”) has met his equal: ”Norman and I are alike in this, that we both tend to suspect others of putting us down, and we strike before we‘re struck.” The high-strung Baldwin describes himself as ready to rumble: “I was then (and I have not changed much) a very tight, tense, lean, abnormally ambitious, abnormally intelligent, and hungry black cat” (269). In Norman he faces his opposite (and double): “two lean cats, one white and one black, met in a French living room. I had heard of him, he had heard of me. And here we were, suddenly, circling around each other. We liked each other at once, but each was frightened that the other would pull rank. He could have pulled rank on me because he was more famous and had more money and also because he was white; but I could have pulled rank on him precisely because I was black and knew more about that periphery he so helplessly maligns in The White Negro than he could ever hope to know” (270). But no sooner has Baldwin invoked this macho standoff (as if the New York intellectuals meet West Side Story, the reigning Broadway hit of the day) then he denaturalizes it: “Already you see, we were trapped in our roles and our attitudes: the toughest kid on the block was meeting the toughest kid on the block. I think that both of us were pretty wary of this grueling and thankless role, I know that I am.” But extricating oneself is easier said than done: “one does not cease playing a role simply because one has begun to understand it.” These roles—preordained clichés that taboo the unexpected– are at once survival strategies and “fulfill something in our personalities” while also imposed by “the world” to “trap and immobilize you.” To outwit, or at least mitigate, the force of these reifications Baldwin will practice what he calls a “watchful, mocking distance” (270-271).

He first exerts that mocking distance upon “the prison of masculinity,” a target he had already critiqued in a 1954 essay on Andre Gide (231). But with Mailer Baldwin finds himself caught up again in the dreary American routine of macho posturing, for the author of “the White Negro” insists on it. The “myth of the sexuality of the Negroes which Norman, like so many others, refuses to give up” is a myth that comes with a high cost: it “means that one pays, in one’s own personality, for the sexual insecurity of others.” This makes the “relationship” of a “black boy to a white boy” a “very complex thing” (270). Baldwin has to “pay” for Mailer’s obsession by submitting to the straitjacket of “toughest kid on the block” enraged at infantile white “innocence” and its “weird nostalgia” for “the breast that has been taken away.” But now Baldwin grants that “time and love have modified my tough-boy lack of charity” (270). Love—his warm affection for Mailer—turns the racial/sexual battleground, which had been threatening to dominate, into one strand the essay weaves into the “love letter” it is. In a startling intimacy of address, Baldwin says: I take Norman “very seriously, he is very dear to me,” and “the night we met, we stayed up very late, and did a great deal of drinking and shouting. But beneath all the shouting and the posing and the mutual showing off, something very wonderful was happening. I was aware of a new and warm presence in my life, for I had met someone I wanted to know, who wanted to know me” (269, 271).

Though “I am a black boy from the Harlem streets, and Norman is a middle-class Jew,” Norman is “very dear” not least because, like Baldwin, he started as an outsider to the literary establishment, who embarked on a “terrifying adventure,” beginning from nowhere, to become a famous American writer. With success comes incessant demand for new product. So the daily question is how to sustain the pace while keeping “despair” away as one sits alone at the typewriter. The temptation to leave one’s desk is hard to resist, especially when the “real world” offers seductions—“opportunities”—“to be good, to be active and effective, to be admired and central and apparently loved” (274). After having “fought so hard to wrest from the world fame and money and love,” Baldwin is now left wondering (with Peggy Lee): is that all there is? “Here I was, at thirty-two, finding my notoriety hard to bear” [Baldwin’s fame was to blossom with the publication two years later of The Fire Next Time]. But I “could not undo the journey which had made of me such a strange man and brought me to such a strange place” (273).

The “strange place” is American literary celebrity, a jet set society founded on the international prestige of literature in the fifties and sixties, and already a relic of the past by the time Baldwin died in 1987. In that world fraternal rivalry and competition among peers are the coin of the realm. Baldwin and Mailer are fond of each other while convinced of one another’s distinct limitations (black jazz musicians “really liked Norman” but “did not for an instant consider him as being even remotely ‘hip’… They thought he was a real sweet ofay cat, but a little frantic” (272) (this last word noting the fatal want of ease that is a sine qua non of sophistication); Mailer tells us in “Some Notes on the Talent in the Room” that Baldwin not only perfumes his pages but pulls his punches, is “incapable of saying ‘Fuck you’ to the reader” ((1992: 471). Baldwin learns this verdict in the living room of James Jones’s Paris apartment; Bill Styron is also there and “the three of us sat in Jim’s living room, reading aloud, in a kind of drunken, masochistic fascination, Norman’s judgment of our personalities and our work.” The “condescension” of the judgment “infuriated” Baldwin, but he soon cools down, realizing how “childish” are Mailer’s remarks. “No one can be more lewdly vicious” than an “imitation libertine,” he says of Norman (277).

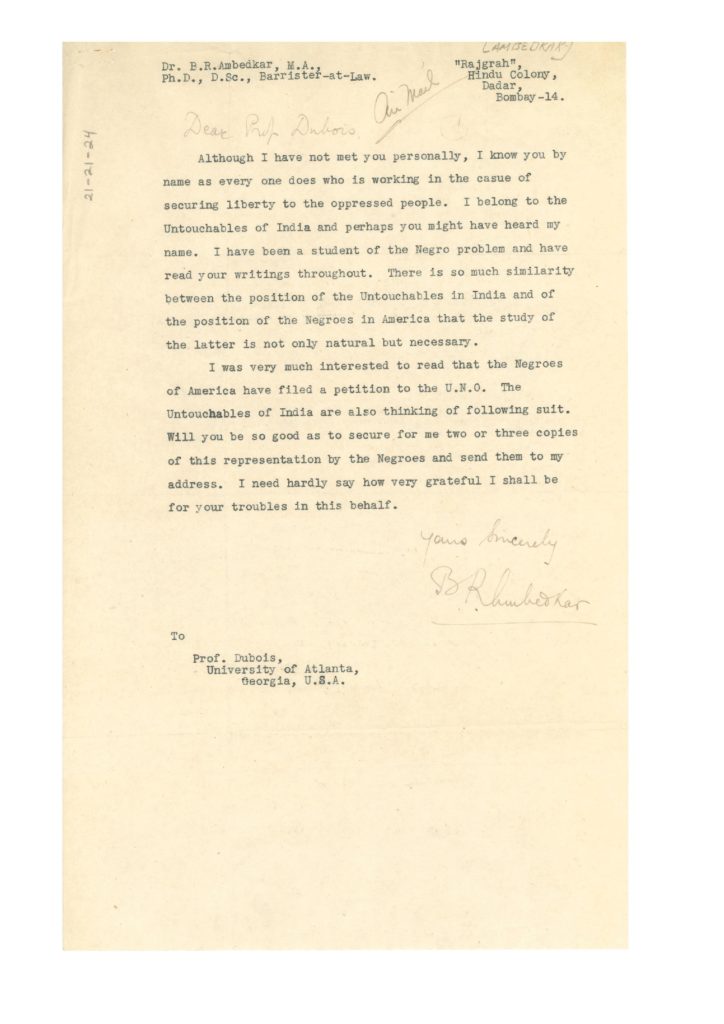

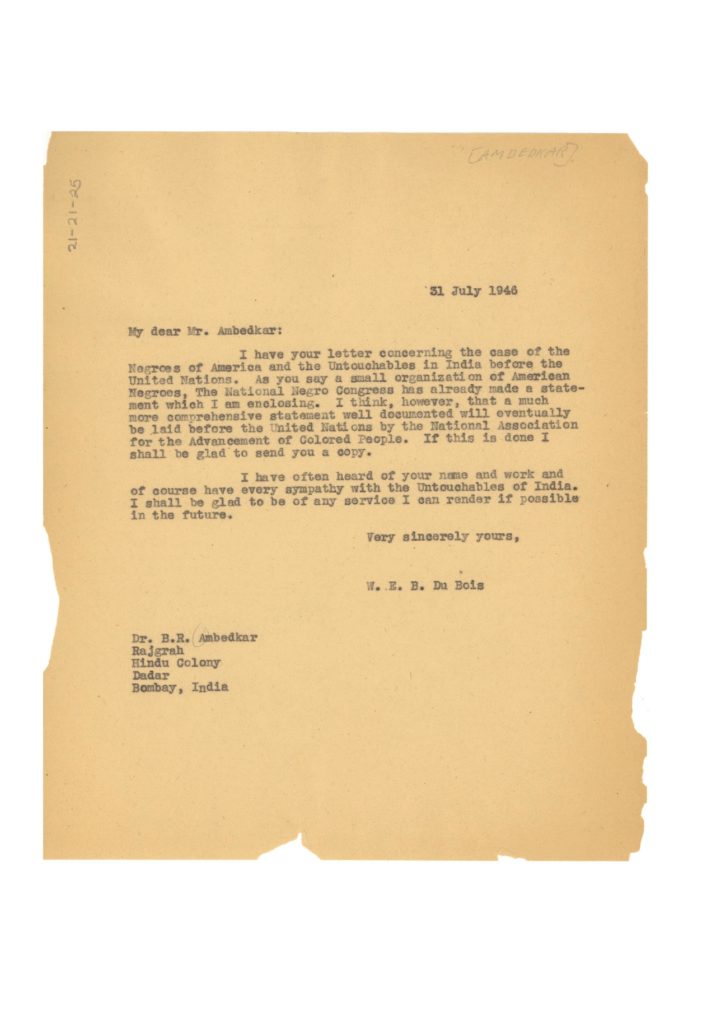

But the trading of insults should not distract us from the essay’s deeper, more daring move—publishing the interracial friendship of co-workers in the kingdom of American celebrity culture (to adapt Du Bois). Theirs is an intimacy founded on resemblance, which is why Baldwin says at the outset: “I have no right to talk about Norman without risking a distinctly chilly self-exposure.” They share life lived at a high altitude, a life of jostling camaraderie that for Baldwin was also a realm of equality. After all, one can be competitive only with someone you have already recognized as an equal. The two men both “get a big bang out of being the center of attention” and enjoy together the beach at Provincetown, and both collect an ‘entourage” “pitifully far beneath” them, and both face the conundrum that afflicts the famous (if not only them): how can I be released from “the prison of my own egocentricity?”

Although “celebrity,” like “sophistication,” usually sums up for reflexive moralists the serpents in the garden of American innocence, the postwar world of American literary/cultural celebrity inhabited by a Baldwin, an Ellison, a Duke Ellington (among other paragons of style) was a new kind of aristocracy and furnished respite from the invidiousness of Jim Crow. For the price of entry neither whiteness nor blackness mattered, only success (“fame and money and love”) as measure and proof of one’s fulfillment of the ambition, shared by Baldwin and Mailer, to make a revolution in consciousness. This lofty goal required as many readers as possible, as much public “exposure” as possible—Baldwin achieved the cover of Time Magazine—and kept one busy making the endless rounds, among them Hugh Hefner’s Playboy mansion or David Susskind’s “Open End” talk show. Baldwin said it was hard at a certain point to resist the “show business” of American celebrity. He succumbed at times, we have seen; and Mailer did too. So by the end of the essay, when he learns that Norman is running for Mayor of New York, Baldwin says: “It’s not your job.” “You son of a bitch, you’re copping out” because you are one of a very few who “might help to excavate the buried consciousness of this country” (283).

Loyalty to the demands of one’s “job”—a nexus of aesthetic, ethical and political imperatives—is what Baldwin calls “responsibility.” And he demands it in a moment mixed with the anger and the respect and fraternal affection of one professional for another, both of whom are now on the inside of the global literary world, flirting with its constant lure of fatal capitulation to destructive narcissism. “The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy” permits us to see the rude candor of truth telling, the coercive masculine rituals, the envy and combat, the pleasure, the glamour, and affection, while insisting on ethical, political, aesthetic seriousness, in sum: commitment to one’s job. Rather than privileging this last quality, Baldwin’s sophistication exposes the whole panoply, calmly keeps all of this tumult in play by upholding “a kind of watchful, mocking distance between oneself as one appears to be and oneself as one actually is” (271). In other words, by banishing the Isabel Archer fantasy of transparency, he instead takes as a given the immobilizing roles—cliches and other forms of hyper-legibility that foreclose experience–that are the traps the world sets. Then he is able to let his “mocking“ self-consciousness function as the ”discipline” that unlocks these traps and releases the ease of his unprecedented performance of sophistication embodied in his “love letter” to Norman Mailer.

As a kind of coda, I want to ask from whence did his sophistication come; that is, how did Baldwin become Baldwin? As if in answer he pointed to improvisation. I “had to make” myself “up” as I “went along,” he notes in “Black Boy Looks at the White Boy,” since “the world had prepared no place for you, and if the world had its way, no place would ever exist” (279). Luckily, he had a guide, had been “taken in hand,” “escorted into the world,” as a ten year old, “by a young white schoolteacher, a beautiful woman, very important to me” (480). Orilla “Bill” Miller conducted his aesthetic education, gave him “books to read and talked to me about the books, and about the world…and took me to see plays and films, plays and films to which no one else would have dreamed of taking a ten-year-old boy. I loved her, of course, with a child’s love; didn’t understand half of what she said, but remembered it; and it stood me in good stead later” (480). But it was what Bill Miller did not say but came to embody that most counted. Her cultivation of sophisticated taste in her protégé was important, but even more so was her whiteness. “It is certainly partly because of her, who arrived in my terrifying life so soon, that I never really managed to hate white people.” Like Bette Davis–with her “pop-eyes popping,” who “when she moved, she moved just like a nigger”–proving that a rich white movie star could also be ugly (“She’s uglier than me!”) hence not inherently Other, Bill Miller fractured the sense of whiteness as the menacing monolithic enemy. In her bohemianism and radicalism, in her reliability and compassion and concern, she was not white for Baldwin in the way all other white people were. Her “difference,” he now realizes, had a “profound and bewildering effect on my mind…. From Miss Miller, therefore, I began to suspect that white people did not act as they did because they were white, but for some other reason. She too was treated like a nigger, especially by the cops, and she had no love for landlords” (482, 481).

In her human goodness Bill Miller demystified “color” as an explanation for racism and planted the seed of Baldwin’s famous, seminal statement near the end of The Fire Next Time that “color is not a human or a personal reality; it is a political reality. But this is a distinction so extremely hard to make that the West has not been able to make it yet” (345-346). In other words, in conducting his aesthetic education, Bill Miller simultaneously politicized her precocious student. The political for Baldwin is close to the pragmatic for it involves asking oneself: what use can be made of the facts as we find them. What “use” can be made of my “strangeness,” my experiences, the “American Negro past,” he asks himself (345). And this habit of interrogation helped him avoid surrendering to white supremacy, avoid turning it into a fetish feeding boundless rage, which makes one sound, in this “racist country,” “familiar and even comforting,” the “familiar rage confirming the reality of white power” (412).

To temper one’s potentially devouring rage against white supremacy as all-powerful, and impervious, allows pragmatic, political moves. He salutes as “aristocrats” the black actors who make them. Baldwin uses the word to honor the endurance of black children calmly walking through vicious mobs to get to school. Near the end of The Fire Next Time, he writes: “The Negro boys and girls who are facing mobs today come out of a long line of improbable aristocrats—the only genuine aristocrats this country has produced…They were hewing out of the mountain of white supremacy the stone of their individuality…. I am proud of these people [here he is speaking also of “the unsung army” of black people who helped secure funds for black schools] not because of their color but because of their intelligence and their spiritual force and their beauty” (343-344). They are “genuine aristocrats” because in their poise and sophistication they embody not only the “great spiritual resilience not to hate the hater,” but they also make something out of the condition in which they are embedded. They use it, “hewing” their inwardness, their individuality, “out of the mountain of white supremacy.” Baldwin suggests that the capacity for making is not only a political but an aesthetic practice when tells his nephew at the end of his letter that begins The Fire Next Time, “You come from a long line of great poets, some of the greatest poets since Homer.” Poets, like aristocratic political actors, are precisely makers (poeisis), creators, who are transforming obdurate realities (294).

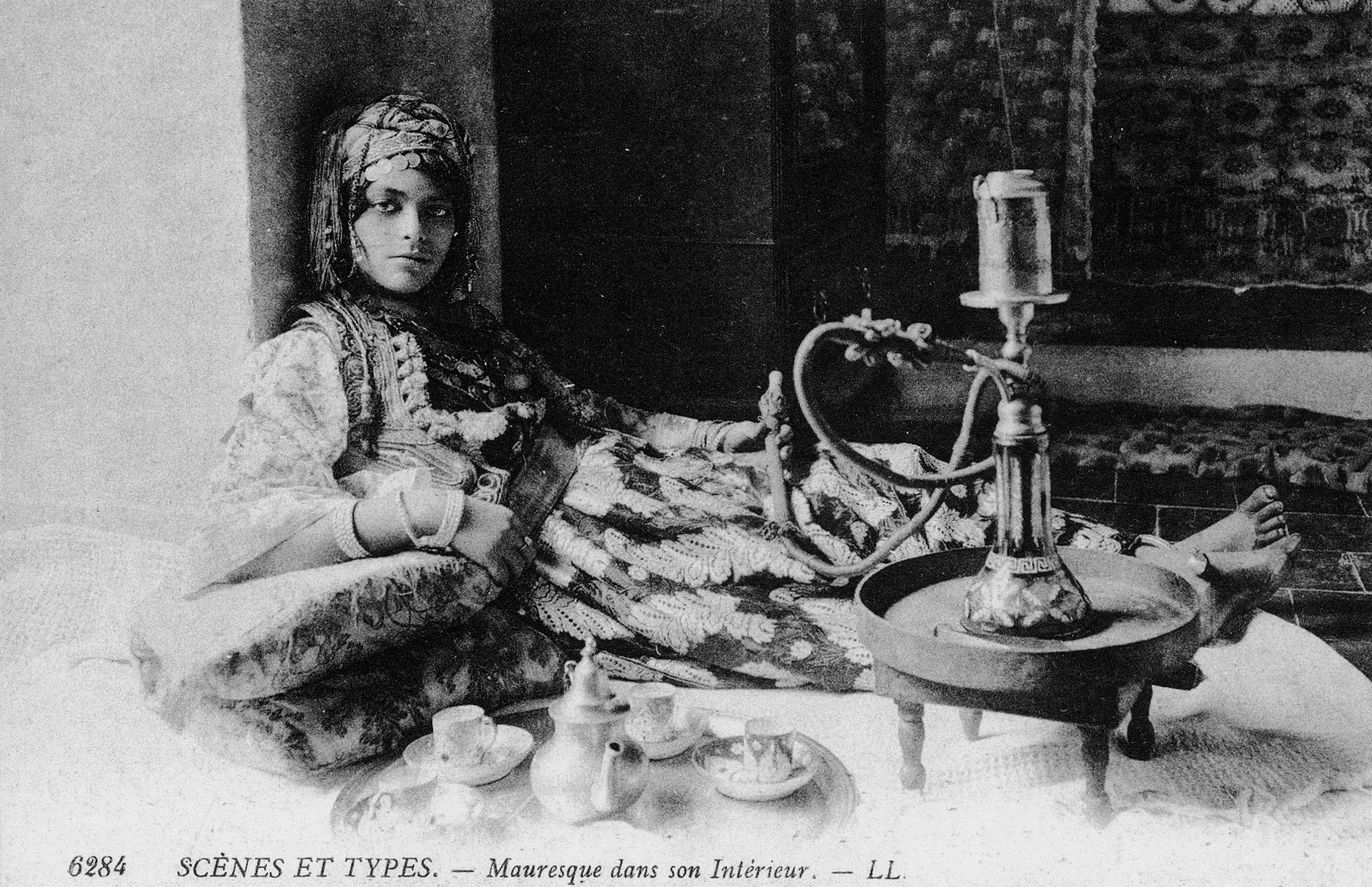

Baldwin practiced the aristocratic making that he preached, using his experience to discover how the delusion of color functioned “as a weapon” to hide one’s “nakedness” and hence to thwart one’s capacity to love. Implicitly referring to his own life of loving white and black people, women and men, Baldwin remarks, “Love” is the “key” to “life itself,” a precious entrance that starts with self-knowledge. Intimacy pries “open the trap of color” to expose one’s “nakedness,” which has no color. “One must accept one’s nakedness”; this can come as “news only to those who have never covered, or been covered by, another naked human being” (366). The other trap, the other flight from nakedness, was fixed identity (of race, of sexual preference). Identity is of course unavoidable but all depends on how one wears it. “Identity would seem to be the garment with which one covers the nakedness of the self: in which case, it is best that the garment be loose, a little like the robes of the desert, through which robes one’s nakedness can always be felt, and, sometimes, discerned. This trust in one’s nakedness is all that gives one the power to change one’s robes” (537). To “trust in one’s nakedness”: such poise is not a Rousseauvian pursuit of transparency but rather the ultimate sophistication, emptying the word of its usual armor and artifice. Let this remarkable, insufficiently known statement (from The Devil Finds Work, 1976), stand as Baldwin’s distillation of his life and art’s still exhilarating, still daunting, imperative.

Ross Posnock teaches American literature at Columbia University; his most recent book Renunciation: Writers, Artists and Philosophers who Abandon their Careers (Harvard, 2016) was a TLS Book of the year and short-listed for the Christian Gauss Award.

References

Baldwin, James. 1998. Collected Essays. New York: Library of America.

Baldwin, James. 2011. The Cross of Redemption: Uncollected Writings. New York: Vintage.

Baraka, Amiri. 1991. The LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka Reader. New York: Thunder’s Mouth.

Barnouw, Jeffrey. 1993. “The Beginning of ‘aesthetics’ and the Leibnizian conception of sensation.” In Eighteenth-Century Aesthetics and the Reconstruction of Art, edited by P. Mattick, 52-95. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press.

Brustein, Robert. 1964. “Everybody Knows My Name.” New York Review of Books, December 17.

Buckley, William. F. 1965. Cambridge Union Debate with James Baldwin.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oFeoS41xe7w

Burke, Peter. 1995. The Fortunes of the Courtier. University Park, PA. Penn State University Press.

Castiglione, Baldesar. 2002. The Book of the Courtier. Translated by Charles Singleton. New York: Norton.

Cohen, Rachel. 2004. A Chance Meeting. New York: Random House.

Crase, Douglas. 2004. Both: A Portrait in Two Parts. New York, Pantheon.

D’Angelo, Paolo. 2018. Sprezzatura: Concealing the Effort of Art from Aristotle to Duchamp. New York: Columba University Press.

Dupee, F.W. 1963. “James Baldwin and the ‘Man.’ New York Review of Books, February 1.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. 1925. The Great Gatsby. New York: Scribner’s.

James, Henry. 1984. Literary Criticism. New York: Library of America.

Javitch, Daniel. 2002. “Preface.” Castiglione, Baldesar. 2002. The Book of the Courtier. Translated by Charles Singleton. New York: Norton.

Jefferson, Thomas. 1988. The Adams-Jefferson Letters. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Kelly, Ian. 2006. Beau Brummell: The Ultimate Man of Style. New York: Free Press.

Lawrence, D.H. 1971. Studies in Classic American Literature. London: Penguin.

Leeming, David. 1994. James Baldwin: A Biography. New York: Knopf

Leopardi, Giacomo. 2015. Zibaldone. Translated by Michael Caesar and Franco D’Intino et al. New York: Farrar, Straus.

Litvak, Joseph. 1997. Strange Gourmets: Sophistication, Theory and the Novel. Durham, NC:, Duke University Press.

McCarthy, Mary. 1989. “A Memory of James Baldwin.” New York Review of Books, May 27.

Mailer. Norman. 1992. Advertisements for Myself. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press.

Mencken, H.L. 1987. H.L. Mencken’s Smart Set Criticism. Washington, D.C., Regnery.

Menke, Christoph. 2012. Force: A Fundamental Concept of Aesthetic Anthropology. Translated by Gerrit Jackson. New York: Fordham University Press.

Morrison, Allan. 1961. “The Angriest Young Man.” Ebony, October.

Rousseau, Jean–Jacques. 1953. The Confessions. Translated by J.M. Cohen. London, Penguin.

Rousseau, Jean–Jacques. 1964. The First and Second Discourses. Translated by Roger D. and Judith R. Masters. New York: St. Martin’s.

Starobinski, Jean. 1988. Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Transparency and Obstruction. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tynan, Kenneth. 2002. The Diaries of Kenneth Tynan. London: Bloomsbury.

Wilson, Edmund. 1993. The Sixties: The Last Journal, 1960-1972. New York, Farrar, Straus.