Anissa Daoudi

العربية | Français

So natural is the impulse to narrate, so inevitable is the form of narrative for any report of the way things really happened, that narrativity could appear problematical only in a culture in which it was absent – absent or, as in some domains …programmatically refused.

Hayden White (1980), “The Value of Narrativity in the Representation of Reality”

“Truth for anyone is a very complex thing. For a writer, what you leave out says as much as those things you include. What lies beyond the margin of the text? The photographer frames the shot; writers frame their world. Mrs Winterson objected to what I had put in, but it seemed to me that what I had left out was the story’s silent twin. There are so many things that we can’t say, because they are too painful. We hope that the things we can say will soothe the rest, or appease it in some way. Stories are compensatory. The world is unfair, unjust, unknowable, out of control. When we tell a story we exercise control, but in such a way as to leave a gap, an opening. It is a version, but never the final one. And perhaps we hope that the silences will be heard by someone else, and the story can continue, can be retold. When we write we offer the silence as much as the story. Words are the part of silence that can be spoken. Mrs Winterson would have preferred it if I had been silent.

Do you remember the story of Philomel who is raped and then has her tongue ripped out by the rapist so that she can never tell? I believe in fiction and the power of stories because that way we speak in tongues. We are not silenced. All of us, when in deep trauma, find we hesitate, we stammer; there are long pauses in our speech. The thing is stuck. We get our language back through the language of others. We can turn to the poem. We can open the book. Somebody has been there for us and deep-dived the words. I needed words because unhappy families are conspiracies of silence. The one who breaks the silence is never forgiven. He or she has to learn to forgive him or herself.”

Jeanette Winterson (2011), Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?

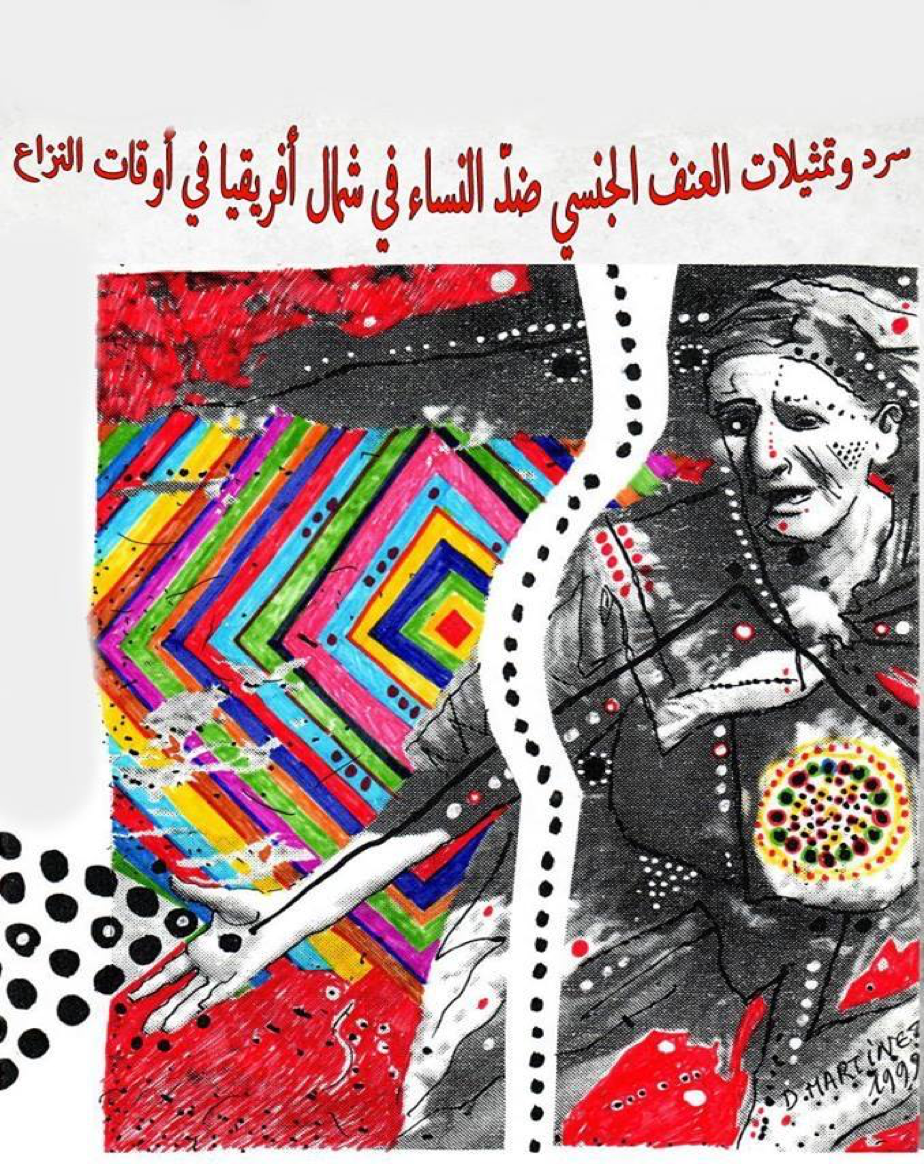

Narrating and Translating Sexual Violence in the Middle East and North Africa is the overarching theme of this Special Issue, which is guided by the natural impulse, to borrow White’s words, to narrate and translate knowing into telling[1]. Culturally, telling stories of violence has been linked to power struggles and therefore, not all stories could be told, particularly in authoritarian regimes. Telling stories is an act of power around who is telling what and to whom? (Foucault, 1977). By telling stories of what really happened, the aim is certainly not to reproduce violence, but to give a voice to the silenced Arab women to tell their stories in order to counter narrate the hegemonic discourse(s) in relation to sexual violence at wartime in the MENA region. The contributors of this special issue; being a combination of academics from different disciplines, activists and feminists from the region and literary writers; are aware of the importance of telling stories that challenge the existing discourses and uncover layers of distortion with a view to the present and the future. Telling is equally important what is being left out, having an eye for details, framing stores in a specific style and genre, using precise language are also as important. Telling “When we tell a story we exercise control, but in such a way as to leave a gap, an opening” as Jeanette Winterson argues. She adds that our story is “a version but never the final one”, yet an important addition to the clusters of stories that form discourse(s). This act of telling or writing is what constructs and produces particular versions of the world. As Baker (2006: 28) puts it “personal stories that we tell ourselves about our place in the world and our own personal history”. By positioning Arab women in the world, we (contributors of this volume) are, as Foucault puts, placing ourselves in the power of network (1978) and agree with Foucault’s idea of power “we must cease once and for all to describe the effect of power in negative terms, it ‘excludes, it ‘represses’, it ‘sensors’, it ‘abstracts’, it ‘masks’, it ‘conceals’. In fact power produces; it produces reality; it produces domains of objects and rituals of the truth” (Foucault, 1977: 194).

This Special Issue seeks to make three valuable and original contributions. To begin with, it is the first time the subject of rape at wartime, a topic considered as taboo, is discussed openly in relation to the MENA region by activists, academics and literary writers from the region in three languages; namely French, Arabic and English. As our theoretical framework is based on the importance of translation as a way of challenging established discourses (Apter, 2013), it became crucial that this unique project has to appear in the three working languages of the MENA region to make information available to scholars, activists, policy makers, students locally and globally, as we believe that sexual violence in wartime is a global phenomenon. The second originality of the papers of this issue is about the content it reveals for the first time, especially in relation to Algeria, where there is the Amnesty Law that stands as a barrier against truth. This special issue is a call for justice and a clear rejection to the Amnesty Law (2005). More importantly, the third point is related to the fight against silencing women and for empowering them to narrate their stories in order to write a complete version of history. By so doing, women are not only putting the records straight, but also helping other women (locally, regionally and globally) to advance in their just fight against patriarchy, injustice and inequality and not re-invent the wheel.

For this Special Issue, I turn to the past to understand the present and aim to take part in shaping the future. In other words, asking the same question as Turshen’s (2002)

what happened to Algerian women who were once active during the War of Liberation become passive in the Civil War? She starts her article with two quotes: one referring to Mudjahidats describing a site where they planted bombs during the War of Liberation and another referring to an Algerian woman, captured by Islamists during the civil war, where she was used as a slave for sexual and other domestic jobs for ‘the Amir’ (terrorist). The two images seem two centuries apart. The question is indirectly asking the Mudjahidats (female war veterans) about their contributions towards the ‘grand narratives’ of the Algerian War. It is in a way holding them responsible for not telling their stories, for not becoming role models for the coming Algerian generations and for not being agents for change in the same way they acted during the Liberation War. This project aspires to uncover ‘layers of distortions/constructions’ to use Tamboukou’s terms (2013), not only about what did the Mudjahidats not say, but also why and how did their silencing happen. By so doing, the eyes are not only on the past but rather, on the present and future of Algerian women. In the following section, analysis of the reasons and the ways the silencing happened will be provided.

I. Gendering Violence in Algeria: the Role of Language

Algeria, known as the country of The Three Djamilas, an Arabic name, meaning ‘beautiful’ referring to three Algerian women war veterans called (Djamila Bouheird, Djamila Boupasha and Djamila Bouazza), standing for the fighting against the coloniser during the liberation war (1954-1962). While this metaphor ‘the Three Djamilas’ has been used and abused in the whole Arab culture, Algerian women’s contribution to the War of Liberation is present in the Algerian collective memory. The abuse starts, as (Mehta, 2014: 48) states with the image related creation of the “land-female body equation, reducing women to abstract symbols of nation without citizenship rights”. This motherland, as (McMillin, 2007) appears all too frequently in nationalist rhetoric. It is the same hegemonic strategy that excludes women from taking an active part in the nation building process. In fact, the metaphor of the land can be analysed closer based on the principle of the ‘conceptual metaphor theory’, by Lackoff and Johnson, 1980, in which the target domain is related to the image of ‘cultivation’, ‘strength’ and ‘security’. This metaphor leaves no room for negative association with al mudjahidats (female war veterans). However, in framing the Djamilas as ‘French’ educated ‘elite’ Algerian ‘Muslim’ girls, the ‘abuse’, to use Thomas’s word ‘cultural violence’ becomes clearer, particularly with the Algerian Arabicisation movement in post-independence in the 1970s, where the same ‘French’ educated women were sent back to the private sphere because they did not master ‘Standard Arabic’, the official language according to the Algerian constitution. History was written by Arabophone Algerian men, leaving no room for women to narrate or archive their stories. In 1974, Ministry of Mudjahideen (the Ministry of Veterans Affairs) reported that 11,000 Algerian women had fought for the liberation (about 3% of all fighters); Amrane Minne (1993) thinks this is a serious underestimation of women’s participation. She adds that of this number, 22% were urban and 78% came from rural areas; these percentages mirror exactly the rate of urbanization in Algeria at that time. The Mudjahidats battle was not with the colonizer only, but was also to free women from ignorance and servitude. Urban educated women joined the rebel forces and went to the villages where they taught illiterate peasant women, the reasons for their independence struggle. Studies reveal that after independence, many faced rejections from their societies and could not reintegrate, some for being raped, others because they had frequented men). From those who managed to find jobs, some were forced by their husbands to return to their traditional jobs. Assia Djebbar’s film La Nouba des femmes du Mont Chenoua (1978) is a representation of colonialism as well as her own women’s culture. In this film, Djebbar stresses the importance of history and memory and asks questions about: whose history is Algeria’s? Who speaks it and to whom? And in what language? The exclusion of French educated Algerian women was not limited to Mudjahidats but also included a generation of Algerians educated in French; even decades after independence (see Chapter One). The following section will provide an analysis of what it felt like living as a woman in the 1990s, known as the ‘Black Decade’ in Algeria.

II. Memories of Algerian Women in the 1990s

The civil war has been described as one of the most brutal periods in independent Algeria. It has been estimated that more than 200,000 people were killed and thousands “brutally wounded, displaced, abducted and sexually violated, according to the Amnesty International Report of 1996” (Mehta, 2014: 69). Independent Algeria experienced nothing other than a one party repressive regime, where corruption, unemployment, nepotism, gender discrimination, and minority segregation were commonplace. In the 1980’s, the country was ready for an explosion of some sorts. The crisis was felt economically, politically, and socially and people took to the streets in what is known as ‘the bread riots’ on October the 5th 1988. The uprising started off peacefully but soon the military brutally crushed the protestors. The Islamists capitalised on the tensions and started to present themselves as the rescuers of the country. They wanted to be seen as the ones to reinvent Algerian identity, which for them was still Francophone. As Zahia Salhi (2010) argues, the military became more militarised and the Islamists engaged in armed struggle, and as a result the country was dragged into one of the most horrific moments of its history. Civilians were the ultimate victims, particularly women. In fact, Salhi believes that women became a deliberate target for the Islamic fundamentalists as early as the 1970s. She explains how the discriminatory provision of the Family Code exacerbated and legitimized violence against women and made it difficult for them to deal with the consequences of widespread human rights abuses (2010). Marnia Lazreg calls 1984[2] “the year of the rupture between women and their government and women and the radical questioning of the state’s legitimacy”.

Dalila Lamarene Djerbal describes the situation:

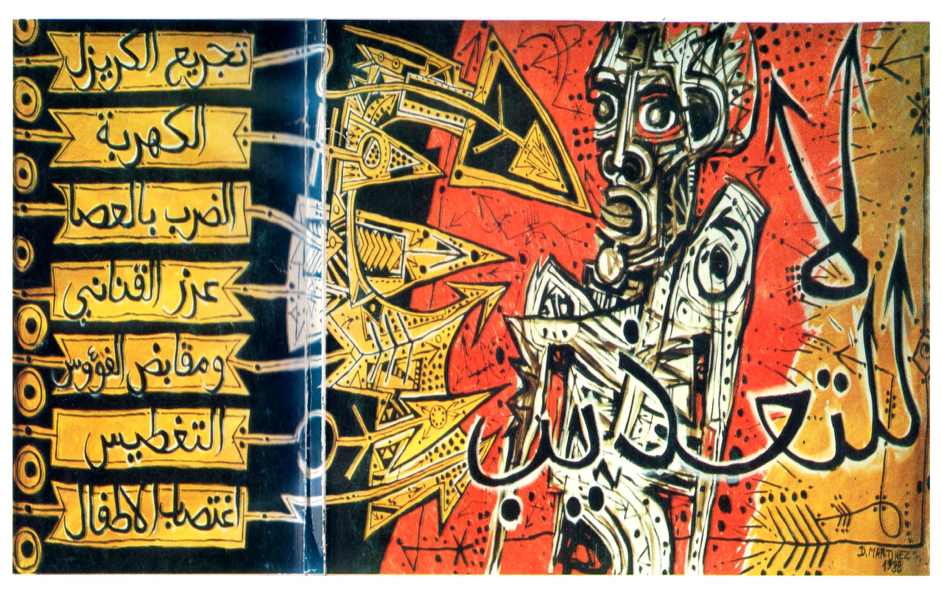

Physical violence on a large scale, then murders of women who do not respect the dress code or rules of conduct; assassination of female citizens charged with supporting the authorities(le pouvoir) or women related to the members of the security services; the obligation for women and families to support the armed groups and beginnings of rape through forced marriages, the multiplication of kidnappings, rape in the guise of what is known as zawāj mut’a[3], abductions of women, segregation, collective rape, torture, murder and mutilation of the entire territory.[4]

The quote above captures the physical violence exercised against Algerian women, which undoubtedly left psychological scars. It summarizes the different pretexts under which women were targeted. The first is related to women in the public sphere and to ‘respectable’ dress code and conduct. The concept of hijab[5] started to circulate in the mid-1970s and the beginning of the 80s, brought by Arab teachers who came to the country under the Arabisation movement and who had links with the Muslim Brotherhood movements. Their aim was the Islamisation of Algeria which according to them was still Francophone. A large number of Algerian women were forced to wear the hijab (the veil) and those who refused to do so receive death threats and in some cases were killed and used as examples to terrorize other women. A Fatwa[6] legalising the kidnapping and temporary marriage of women was issued, in a very similar way to how Yazidi women are treated under ISIS rule today. According to Islamists, hijab[7] is what distinguishes a Muslim woman from a non-Muslim one. It is also what sets the limits between the private and public spheres. All these strict rules justified the physical violence and the killing of women who refused to abide by the religious rule. The first victim was the famous case of Katia Bengana, a 17 year old high school girl in Blida, who had been warned but told her mother: “even if one day I will be assassinated, I will never wear hijab against my will. If I must wear something, it will be the traditional dress of Kabylia, rather than the imported hijab they want to force on us” (Turshen, 2002: 898). Katia’s statement shows how defiant she was, even though, she suspected that she would be killed for her strong views. Additionally, her Kabyle identity was more important to her. She refers to hijab as an ideology imported and forced on Algerians from the Arabian Peninsula in reference to the Wahhabi[8] ideology. This sentiment was shared by a large number of Algerians who claim that their Algerian Islam, under which they were brought up, had its own particularities and that they did not need lessons about Islam from any other source.

Twenty years later, her sister writes a post on Facebook and says: “I cry, I rage against these veiled women who think they are free while they are muzzled. Katia is a girl who decided for herself, not bend to the macho obscurantism of the Islamists. How many Katia(s) do we so that one day these women can finally be free? Katia should be viewed as a symbol of struggle against the medieval spirits. She was courageous and and was ready to go all the way for her convictions, a free woman, a real Tamazight as was the Queen of the Aures, an example of strength and intelligence”[9] (26.01.17). At the Birmingham University Conference, October 2014 on ‘Narrating and Translating Sexual Violence in the MENA Region: the role of Language’, Mrs Wassyla Tamzali, referred to Katia’s case and stressed that she should not be remembered as Berber, instead, she should be celebrated as an Algerian woman (see article by Mrs. Tamzali in this issue). She adds that by dividing citizens as Berbers and Arabs, Algerians fall into the colonial ideology of ‘divide and rule’. Katia was not killed because she was Berber, but because she refused ‘political Islam’. For Tamzali, talking on behalf of Katia is crucial and making Katia’s voice heard is just as important. She chose to make Katia’s case a national issue because she is aware that there are more women like Katia in Algeria. Recent reports from areas in Iraq and Syria, under ISIS control, show how women are still subjected to similar circumstances of rape, killing and sex slavery. Thus, Tamzali’s call is of global significance and is a result of her years of working for the United Nations, dealing with the plight of Women in Bosnia.

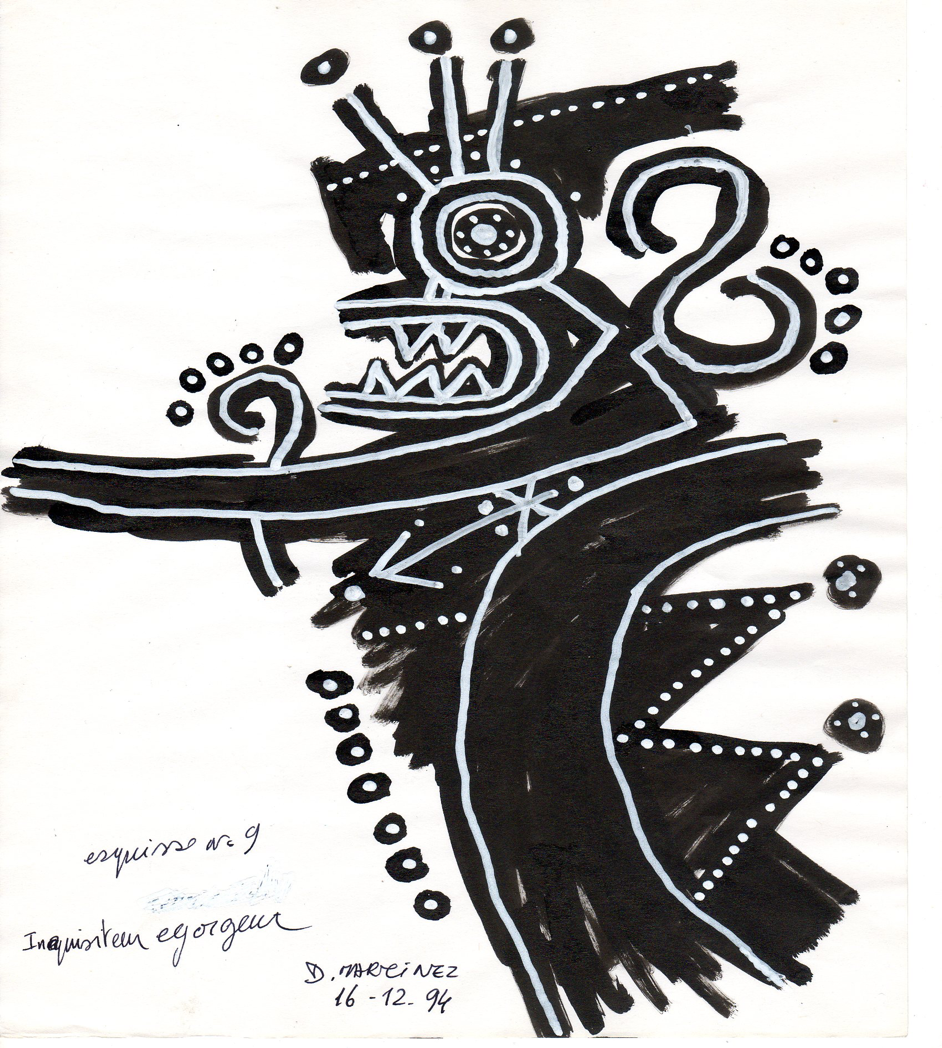

The second issue in Lamarene’s quote relates to the targeting of female citizens “charged with supporting the authorities (le pouvoir) or women related to the members of the security services”. This category of women includes a large segment of the Algerian population, who are wives, sisters or mothers of men working for the security services, police force, army, called by the fundamentalists the ‘tyrants’ – in Arabic taghut[10]’. The latter is a word from classical Arabic that takes us immediately to the usages of the word in the distant past. The word is mentioned in the Quran (Surat al Nahl/the Bee)[11]. In this case the ‘tyrant’ or the ruler is referred to as ‘evil’. The eradication of evil thus becomes a duty for the believer. This conceptual metaphor can be used to explain the process by which the extermination of the non-believer becomes normalised. Using the image of the taghut evokes various images that are directly related to Qur’an and also to the pre-Islamic period where people worshipped other forms of gods, something that differentiates the believer from the non-believer. It recalls the image of the ‘evil’ and the ‘unjust ruler’. The two concepts are sufficient, according to, for example, the grand Mufti (preacher) of Saudi Arabia[12] to justify the death penalty.

Other concepts started to appear in Algerian society at this time: Dalila Lamarene Djerbal refers to Zawāj al Mut’a, a term introduced by Islamists referring to a form of temporary marriage practised by some Shi’i Muslims in the Middle East but not in North Africa. This is unknown in Algeria, where the majority of the population are Sunnis. Other forms of marriage also appeared with the rise of Islamism, such as zawāj al misāyr (again a temporary form of marriage accepted in the Sunni sect of Wahhabism). Other forms of attack on women’s bodies under different terminologies started to make their way into Algerian society. Fadhila Al Farouq’s novel, refers to the word rape in Arabic and places it in inverted commas “الاغتصاب” /al ightisāb/ as a controversial term. Yet, she explicitly explains its etymological roots to Classical Arabic. By so doing, Al Farouq implicitly attacks the religious institution for using ‘Islamic concepts’ as symbolic capital (see Chapter One).

Djerbal’s quote captures the atrocities Algerian women went through during the ‘Black Decade’. Violence was both real and symbolic against civilians, particularly women who, as indicated by Djerbal, were collectively raped, tortured and murdered in the most dramatic ways (see below the discussion on the killing of female teachers in the western part of Algeria). In the 1990s, ordinary women in Algeria took to the streets to denounce the violent discourses against them. In 1994, the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) called for a boycott of schools. However, in spite of numerous school burnings and murders of teachers, women still brought their children to classes in acts of defiance. Violence grew as it met resistance from government and citizens, including women. The terrorists “stepped up their activities, establishing roadblocks and killing everyone ambushed in this way” (Turshen, 2002: 897). Other acts directed against women included the issuing of the fatwa legalising the killing of girls and women who did not wear the hijab. Another fatwa legalised the kidnapping and temporary marriage of women. According to the FIS, hijab is what distinguishes a Muslim from a non-Muslim woman. It is also what puts the limits between the private and public spheres. All these edicts justified the killing of women who refused to abide by the religious rules. The next section will shed light on Algerian women’s organisations and their fight against what was happening.

III. The Role of Women’s Organisations in Algeria in the Black Decade: Resilience

Algerian women were subjugated to the worst kinds of violence way before the civil war. In public discourses by the Islamic party (FIS[13]), some women like feminists were portrayed as non-believers, westerners, immoral and therefore, there was an urgent need to bring them back to their traditional roles. They, according to the FIS, were occupying jobs that were supposed to be for men. Unemployed men favoured this particular discourse at the time where the economic crisis hit the country due to corruption; fall in prices of oil in a country that relied primarily on natural resources. Algeria became more and more hostile to the presence of women in the public sphere. Feminists were harassed, prevented from doing their jobs and even not allowed to live without a male relative (like brother, husband, son, what is called mahram. The 1984 Law, (as explained in Chapter One), did not help either. In fact, it institutionalised violence and discrimination against women. Ait Hamou (2004, 117); one the founding members of Réseau Wassyla argues that the Algerian government co-opted the conservatives, and later, Muslim fundamentalists, to protect their interests and stay in power. Various governments have made compromises and sacrificed women’s rights to keep peace with the fundamentalists[14] . For example, in 1989, “conservatives within the FLN[15] colluded with Islamists to introduce measures against the emancipation of women, for instance more religious education in primary schools; making sports not compulsory for girls; and so on” (ibid). In other words, the complicity of the FLN, in the educational system in Algeria has always been going on for years.

Globally, when women were facing violence on a daily basis, the whole world turned a blind on what was going on. It is, as Ait-Hamou argues, “since 11 September, the world, and particularly, the United State, seems to have suddenly realised that Muslim fundamentalism, in its extreme form of terrorism, is a real threat”. She adds “many of us cannot help feeling bitter about such an attitude, for we fought fundamentalism and terrorism in isolation, with our bare hands for a good number of years, while fundamentalists who committed the most atrocious crimes in our countries were getting support from the same governments that are now dictating to the rest of the world how to ‘fight terrorism”. This feeling of bitterness about being left alone with no support at all neither from their fellow Arabs nor form the rest of the world is what women and men repeat now when asked about why they did not join the so called ‘Arab Spring’. Another striking issue that Ait-Hamou refers to is the Amnesty Law of 1999, which is to date criticised by most feminist organisations.

The aim of the Amnesty Law was to bring closure to the Algerian Civil War by offering an amnesty for most violence committed in it. The referendum on it was held on September 29, 2005, and it was implemented as law on February 28, 2006. Critics, however call it a denial of truth and justice to the victims of the abuses and their families. One example of the voices against the Amnesty Law is Cherifa Keddar, the founder of Djazairouna Association, created on October 17, 1996, following the assassination of her sister and brother after a targeted attack on her family, including their mother by Islamists. Cherifa united with the survivors of terrorism to give them a voice that denounces the Amnesty Law and asks for justice. Bennoune gives detailed information about the work of this organization in this issue.

Feminist organisations were fighting against fundamentalism, based on theocracy and patriarchy, as the source violence. They all believed that the early 1980s was the start of fundamentalism in Algeria. They agree that the Friday Sermons diffused on loudspeakers[16], focusing on women bodies, describing them as immoral for wearing for example, lipstick or going out unveiled. University campuses were also attacked and the authorities kept a low profile. In June 1989, a group of fundamentalists set fire in public to a house that belonged to a divorced woman, who lived with her children. Her three children were burnt to death. Women’s groups denounced the crime and organized the first demonstration in the streets of Algiers. Silence complicity from the State helped Islamism to rise. In years 1992-1993, thousands of men and women were killed and the country lived in terror. The first woman to be murdered was Karima Belhadj, secretary in the General Office of National Security[17]. Women organisations in Algeria had little choice. They had to strategically survive the atrocities, some wore the veil to avoid confrontations others, resisted that. One needs to look at the Algerian society now to realise that more than help of women are veiled. Women’s rights activists had a national strategy to combat fundamentalism by producing counter-discourse, on many occasions, they occupied the street, carrying photos of those who were killed, at a time when people were terrified. The first public meeting was in 1993 organised by the Gathering of Algerian Democratic Women (RAFD), using mock tribunal against terrorism (Ait-Hamou, ibid). Women’s rights organisations also denounced the American and European discourses, under the name of democracy, that the Islamists were victims, by contributing to international debates using foreign media channels and participating at international conferences. They established many women’s associations like SOS Femmes en Detresse, RAFD and RACHDA continue to combat for women’s right and for providing counter-discourse to fundamentalism.

The history of violence on Algerian women by jihadist groups some 20 years ago now, as Bennoune argues in this issue, the way it happened, the way it was overlooked, the way in which victims were overlooked, neglected and forgotten-should spark outrage globally, as this violence on issue is not on Algerian women only but it is a global issue and understanding it, gives insights into understanding ISIS today. Bennoune’s essay, in this issue, addresses rape in Algeria in the ‘Black Decade’ and provides a true picture of what Algeria during the Civil war was like. She scrutinizes the ways rape was narrated by interviewing survivors, which is to date not an easy task under the Amnesty Law. Her expertise in Law and her fieldwork research on the theme of rape in Algeria and in other parts of the Muslim world contributes to the interdisciplinary nature of this issue. Her essay shows her knowledge of Algeria inside out and her sharp analysis of the events.

To complement Benoune’s article, Daoudi, stresses on the cultural production of the 1990s in Algeria. Her article entitled ‘Untranslatability of Algeria’ challenges Apter’s (2013) concept of untranslatability and presents it not as a homogenous entity but a multiple notion. Translation as a means of disturbing discourses (Apter, 2013) is the basis of the arguments about gender roles and contribution to colonial and postcolonial Algeria. It helps dismantling the narratives that were written by men and bring out the silenced discourses. Through close analysis of the various gender discourses on violence in Algeria, this article shows the manipulations of discourses about Algerian women during colonial and postcolonial Algeria. It also discusses the role of Algerian writers in giving a voice to their voiceless compatriots to help archive their history and to construct their social memory and collective. In addition, it emphasizes the roles of language and translation in the construction of a constantly changing Algeria with an emphasis on the Civil War 1990s.

A specialist in Gender and Islamic Studies, Amel Grami, who worked with Jihadi women in the MENA region brings out an understudied area, I find myself attentive to a number of related themes such as ‘al sabi’ and ‘jihad al-nikah’, on which Grami has published extensively. ‘Jihad al-nikah’, in particular has been a very controversial issue in Tunisia after the Arab Spring. Grami argues that official statements from the Tunisian Home Office declared that indeed there are groups of young Tunisian women who travelled to Syria with the purpose of ‘Jihad al-nikah’. She brings to lights different narratives about sexual violence in Tunisia. The purpose of narrating these stories is not to study the past but to try to understand it in the present, for example, in understanding Yazidi women’s rape in the MENA region (see article by Grami in this Special Issue).

Algerian women’s fight against silence and fundamentalism was not restricted to women’s rights activists on the ground. Other women; writers fought their pens. Djebar, as a pioneer among the generation that lived colonialism and Mokadem are the core of the essay written by Imen Cozzo in this issue. She believes that Algerian women’s silence might be an involuntary social, cultural and ideological act of resistance, a way to bury the atrocious truth and to seal it into a forgotten tomb, she says. Silence was imposed by a colonial reality and continues to be enforced by a postcolonial tradition and society. After independence, many Algerian writers use the same coloniser’s language to resist their assimilation into a backward process or the fight over “outer” and “inner” spaces.[18] Therefore, Cozzo argues that silence becomes a political act through which women subvert the oppressors’ discourse, by retaining their secret world/word.

Violence in the 1990s in Algerian films namely: Rachida, The Harem of Madame Osmane, and Barakat! Is what Rym Quartsi discusses in her article. She looks at films as another medium through which Algerian directors communicated their trauma and pain of the Black Decade. In her essay, she explores the relationship between gender, violence and language. The Black decade is the period when most artists fled the country after receiving death threats. This led to the dismantling of the film industry and the films that were produced were done outside Algeria by external funding.

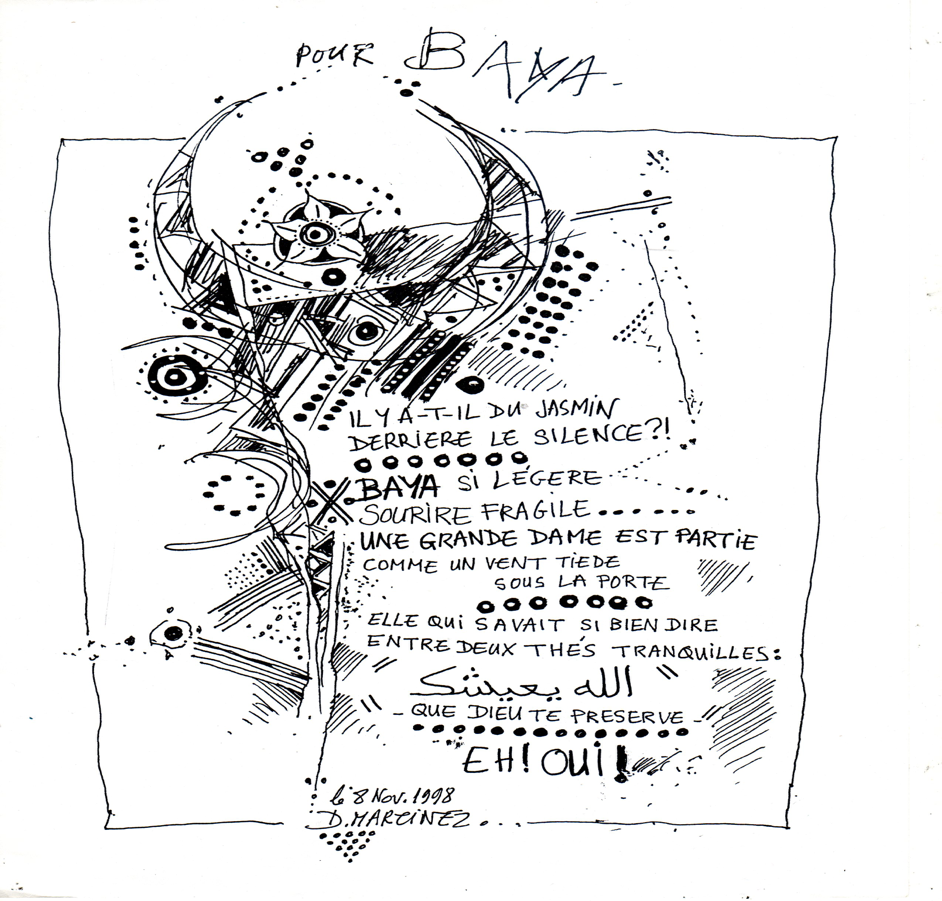

In a comparative study, Bedjaoui recalls the ‘Black Decade’ through the work of the two Francophone female writers Assia Djebar and Maisa Bey. The novels studied, centres on the violence of religious fanaticism that terrified the Algerian society in the 1990s. Similarly, Tamzali writes a letter to katia Benghena, the girl who defied the Islamists and refused to wear the veil. Tamzali warns of the division of the Algerian society into Berber, Arab, Francophone and Aarbophone. She reminds us Katia is an Algerian woman and not just a Berber. In describing how it was living in Algeria during the Black decade, she says: “the country was plunging into civil war, neighbours and brothers killing each other. The pain and the fear overpowered the gaze of our mothers and our lives headed towards barbarism to the sound of heavy boots and the cries of “Allahu Akbar”. Death spread in every corner and the stench of gloomy clouds filled the air.” Finally, a selection of literary texts by Fadhila Al Farouq and Inam Bioud is presented in the three languages. Al Farouq is the first Algerian writer, who chose to fight with her pen, risking her life, to document cases of rape in the 1990s. Bioud’s poem fills our heart with sadness and reminds us of the atrocities of the “Black decade.”

IV. Conclusion

Violence in the recent years has intensified, or at least the advancement in Information Technology made it look intensified. This is to say that violence has always existed but people did not necessarily hear about it and surely did not used to see it happen live. The Internet has facilitated the movement of information, for example, the picture of the Egyptian woman in her bra who was dragged by the Egyptian police officer in Tahrir Square went viral on social media and became known as the ‘the blue bra event’. Other events in the Arab region ‘the so-called Arab Spring/revolution’ are characterised by interesting reactions about the role of women in the fight for freedom, varying from stories about the Egyptian government subjecting female participants to ‘virginity tests’, to horrific stories about collective rape in Tahrir Square (Cairo), to calls by a preacher for sexual holy war in what is known as jihad al nikah (which is basically offering sexual services to comfort fighters against the Syrian regime), using a terminology from Classical Arabic to refer to the wholly war in the new context. All of these stories and many more are narrated and in some cases used and abused to legitimise violent reactions. They are also part of history, which is constructed through narrativation of layers of complex intertwined stories. Homi Bhabha, says “tell stories that create the web of history, and change direction of its flow” (cited in Gana and Härting, 2008: 5). This same view is also shared by Mona Baker who argues that narratives construct realities. It is this line of thought that drive us (female academics from the region), writers, film directors… etc. to publish this issue, aiming to dismantle official narratives and give voice to the silenced narratives of the 1990s. By so doing, we are not voicing narratives from the other who can be geographically distant but we narrate violence as a global phenomenon, as an ethical issue and more importantly as a continuous search for the truth. Below is Tahar Djaout’s slogan that captures the spirit of this Special Issue.

Silence means death

If you speak out, they kill you.

If you keep silent, they kill you.

So, speak out and die

Tahar Djaout

[1] See Hayden White’s etymological definition of both words ‘knowing and telling’ in his article “the Value of Narrativity in the Representation of Reality” in Critical Inquiry, Volume 7, No 1 (Autumn, 1980) 5-27

[2] 1984 was the year when Algeria made changes to the constitution. “The Family Code of 1984 makes it a legal duty for Algerian women to obey their husbands, and respect and serve them, their parents, and relatives (Article 39). It institutionalised polygamy and made it the right of men to take up to four wives (Article 8). Women cannot arrange their own marriage contracts unless represented by a matrimonial guardian (Article 11), and they have no right to apply for divorce. While a man needs only to desire a divorce to get one, it is made a most difficult, if not impossible, thing to be obtained by women” (Salhi, 2003: 30). http://www.artsrn.ualberta.ca/amcdouga/Hist247/winter_2011/resources/Algerian%20Women%20and%20the%20’family%20code’.pdf

[3] Zawāj mut’a, also known as Nikāḥ al-mutʿah (Arabic: زواج المتعة, literally “temporary marriage”), is a type of marriage permitted in Twelver Shia Islam, where the duration of the marriage and the dowry must be specified and agreed upon in advance. The researcher as well as feminists consider this marriage and its equivalent in the Sunni sect (zawāj al misyār) as forms of religiously sanctioned prostitution.

[4] All translations are by the author.

[5] Hijab: consists of wearing a scarf that hides the hair and neck as well as a full length robe.

[6] Fatwa is a religious commandment based on scholarly legal decision.

[7] For more information about the veil, see Marnia Lazreg’s book Questioning the Veil:

Open Letters to Muslim Women (2011).

[8] Wahhabi, in Arabic / al-Wahhābiya(h). Wahhabism is named after an eighteenth-century preacher and scholar, Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703–1792). It is a religious movement or branch of Sunni Islam, which started in Saudi Arabia. It is an extremely conservative form of Islam. For more information, see: David Commins (2006) book: Wahhabism and Saudi Arabia (I. B. Taurus).

[9] See, https://www.facebook.com/Chkovein/?hc_ref=SEARCH

[10] Taghut: an unjust ruler who does not follow God’s rules.

[11]

وَلَقَدْ بَعَثْنَا فِي كُلِّ أُمَّةٍ رَّسُولًا أَنِ اعْبُدُوا اللَّهَ وَاجْتَنِبُوا الطَّاغُوتَ ۖ فَمِنْهُم مَّنْ هَدَى اللَّهُ وَمِنْهُم مَّنْ حَقَّتْ عَلَيْهِ الضَّلَالَةُ فَسِيرُوا فِي الْأَرْضِ فَانظُرُوا كَيْفَ كَانَ عَاقِبَةُ الْمُكَذِّبِينَ

“For We assuredly sent amongst every People a messenger, (with the Command), “Serve Allah, and eschew Evil”: of the People were some whom Allah guided, and some on whom error became inevitably (established). So travel through the earth, and see what was the end of those who denied (the Truth)”.

[12] In a question-and-answer programme, Al Fuzan (the grand Mufti of Saudi Arabia) was asked about whether or not the taghut is a kafir, i.e., non-believer. The Mufti replied:

“أنه مخير بين أن يحكم بما أنزل الله أو يحكم بغيره، أو أن الحكم بغير ما أنزل الله جائز، فهذا يعتبر طاغوتًا وهو كافر بالله عز وجل.””.

In English: “He (the taghut) is asked to rule using God’s words, but if he decides to disobey God’s words/rules, he then is a non-believer in God the gracious”. The ultimate ruler here is God and his obedience is fundamental in Islam.

[13] FIS: Front Islamique du Salut (Islamic Party)

[14] Ait Hammou, ‘Women’s Struggle against Muslim Fundamentalism in Algeria: Strategies or a Lesson for Survival?’ p. 118.

[15] FLN: Front de Liberation National

[16] For more information on how loudspeakers were used, see film: Bab el Oued City https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2jKITX62qCM

[17] For more information, see Ait Hamou’s article: Ait-Hamou_FundamentalismAlgeria.pdf

[18] Amel Grami, “Narrating rape in the Mena region: the role of language”, (Conference: University of Birmingham, School of Arts and Music, Department of Modern Languages, Arabic Section, UK, 10 /10/ 2014.