by Jonathan Farina

This essay was peer-reviewed by the editorial board of b2o: an online journal.

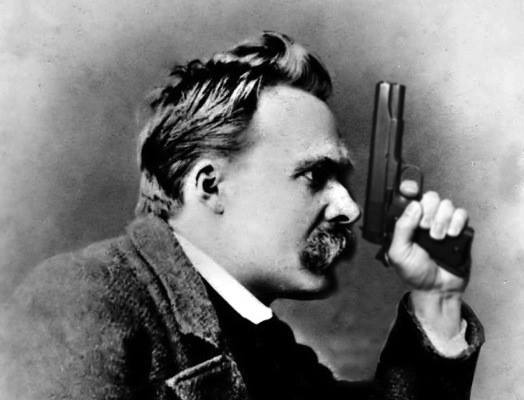

My title puns on Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morals, a work of skeptical philology that aspires to liberate the future by recasting western values as products of a history of distorting or inverting human greatness. Etymological history, the genealogy of words, promises a novel articulation of what counts as good and bad. Nietzsche idealizes ruminative, philological reading, “that venerable art,” as he puts it in Daybreak, “which demands of its votaries one thing above all: to go aside, to take time, to become still, to become slow – it is a goldsmith’s art and connoisseurship of the word which has nothing but delicate, cautious work to do and achieves nothing if it does not achieve it lento” (1975: 5). Slow historicism, then, but neither positivist nor antiquarian, as some modern scholarship has been described: for Nietzsche, “for precisely this [slowness]”, philology

is more necessary than ever today, by precisely this means does it entice and enchant us the most, in the midst of an age of ‘work,’ that is to say, of hurry, of indecent and perspiring haste, which wants to ‘get everything done’ at once, including every old or new book: this art does not so easily get anything done, it teaches to read well, that is to say, to read slowly, deeply, looking cautiously before and aft, with reservations, with doors left open, with delicate eyes and fingers. (1975: 5)

For all its velocity, Dickens’s prose rewards and even personifies Nietzsche’s slow philology. Bleak House, in particular, exemplifies how we might practice a poststructuralist, materialist philology that reanimates the past embedded in the present. And, given the late fad for mindfulness and being present, never mind the topic of this inaugural V21 symposium, “presence” is not a bad word with which to start.

Alert as Dickens is to expressions, by turns axiomatic and idiotic, idiomatic and idiosyncratic, including Bart Smallweed’s “I don’t know but what I will have another” and Snagsby’s “not to put too fine a point on it”; alert to portmanteau words like wiglomeration, and to professional discourses, slang, and puns, to “gammon” and “spinach,” Dickens offers plenty of fodder for philological rumination to rehistoricizes our present word by word (1977: 249, 180). The earliest criticism of Bleak House, favorable and unfavorable, distinguishes the prose style or “manner” of Dickens for its reducibility to small, iterative phrases, “the queerest catch-word,” as Henry Chorley called it, or “congeries of oddities of phrase, manner, gesticulation, dress, countenance, or limb,” in the words of James Stothert (Collins 1986: 280, 279, 294). Critics remarked on how these portable phrases indexed the present, mediated “current table-talk or our current literature,” as David Masson said (Masson 1875: 257-8). This facility translating mannerisms into currency, to condense attitudes into fungible expressions, makes Dickens’s style thematize presentism.

Indeed, the word “presence” serves many times as a synonym for manner and personality in the novel: Mrs. Snagsby, for instance, has a “dentistical presence,” ready to pull the “tender double tooth” of a secret she suspects her husband of holding; and Kenge, for another, has “conversational presence” (Dickens 1977: 316, 760), and so on. With 43 instances of “presence,” 250 uses of “manner,” and a chapter on and thematic investment in “deportment,” Bleak House dwells on the way style and manners coalesce to mediate our temporal experience of and presence in or bearing toward the world. Manner, deportment, composure, disposition, presence, and style: these performances of temporality are miniature fictions with which individuals inhabit times and places and relations that often clash with the actual present, the actual times and places and relations their bodies occupy. Assuming a characterological stance against the imperatives of the present, “presence” and “deportment” are modes of embodied critique. As such, they personify how the philological plenitude of other words readily offer, in their connotations and histories, a critique of the present.

From Kenge’s own system-cementing trowel-wave of the hand to Snagsby’s variously expressive coughs, from Esther’s emphatic humility to Bart Smallweed’s injunction at the legal triumvirate’s sexually-charged lunch at the Slap-Bang— “and don’t you forget the stuffing, Polly!”—telling mannerisms and multivalent words abound in Bleak House (1977: 247). But for polemic purposes let me stick with “deportment” as a salient example. Bleak House recognizes the “currency” of the word, that is, its relevance and fashionable circulation in the present, even as it foregrounds its historicity and ambiguity. Tale the moving reunion of George Rouncewell and Sir Leicester Dedlock: waiting for Bucket to reclaim runaway Lady Dedlock, George offers his “arms to raise … up” the debilitated Sir Leicester, who in turn raises George from despondency: “‘You have been a soldier,” he observes, non-sequitur, “‘and a faithful one’” (Dickens 1977: 696). At the Dedlock’s London home, just where we might think George’s typically awkward manner might put him out-of-place, the soldier shines. He humbly parries Sir Leicester’s praise: “I have done my duty under discipline, and it was the least I could do” (Dickens 1977: 696). He has felt uncomfortable everywhere else, he protests his unfitness for other modes of life (especially the domestic industrial married future exemplified in his brother), but here amidst a fading aristocratic dinosaur George’s deportment reciprocates and makes meaningful Sir Leicester’s, about which Dickens says, “He is very ill, but he makes his present stand against distress of mind and body, most courageously” (Dickens 1977: 694). “Present” here works as both adjective and noun: through his presence, that is to say, through his bearing, he makes present circumstances appear closer to his ideal temporality and structure of feeling. His presence, then, as a sort of regulative fiction, contests his present reality as he and George concurrently revisit the past in their minds and manners.[i]

George and Sir Leicester—odd models, to be sure—might thereby personify here the potential work an interpretative philology might do in reanimating the present with the past. Where traditional philology sought to fix the correct meaning of a word, a reinvigorated, Nietzschean version would eschew determination. As John Hamilton has written, an interpretative philology

may provide a privileged means for holding determinations at bay, for perpetuating community and its constitutive communication, not by fixing a word’s properties conceptually, with sovereign authority, disciplinary control, or tired complacency, but rather by pursuing its transit through time and across cultures and thereby allowing it to be translated, over and over again, on the basis of its very untranslatability. (Hamilton 2013: 21)

In this scene of exemplary deportment, marked by gestures more than words, Dickens nearly redeems an erstwhile unlovable aristocrat, whose virtue accrues to his loving insistence that words and manners remain constant: “I revoke no disposition I have made in her favour. I abridge nothing I have ever bestowed on her. I am on unaltered terms with her” (Dickens 1977: 698).[ii] At the same time, however, the narrative acknowledges the terrific contingency of our reception of these “terms”: “His formal array of words,” the novel says of Sir Leicester’s forgiveness, “might have at any other time, as it has often had, something ludicrous in it; but at this time, it is serious and affecting. His noble earnestness, his fidelity, his gallant shielding of her, his generous conquest of his own wrong and his own pride for her sake, are simply honourable, manly, and true,” and “the lustre of such qualities,” Dickens adds, lest we impugn something decidedly aristocratic to the act, are available to the “commonest mechanic” and “the best-born gentleman” alike (1977: 698). Mannerisms and words that are ludicrous early in the novel thus recur “serious and affecting” “at this time.”

The scene complicates the novel’s preceding travesty of deportment personified in “Old Mr. Turveydrop,” about whom Caddy tells Esther, “No, he don’t teach anything in particular … But his Deportment is beautiful” (Dickens 1977: 169). Turveydrop caricatures the universal “dandyism” and agency of “fashion” that Bleak House disparages, but Turveydrop’s problem isn’t deportment itself so much as his own bad deportment, marked by ill-fitting clothes as much as by his maladjustment to the people around him: he is disposed to a trivial, fantastic, nostalgic version of his past (a fleeting encounter with the Prince Regent) rather than to a meaningful fictional past—like the “Young England” that suits George and Sir Leicester—or the present needs that Esther answers. Like Mrs. Jellyby’s telescopic philanthropy, more literally still like Smallweed on his litter, Turveydrop’s deportment carries him away with himself from the circle that deserves his attention, his caring presence. In his vanity, Turveydrop mocks style as a lack of substance and a deformity of truth, as Dickens makes plain with his overstretched outfit. Turveydrop, like the Prince Regent before him, has no sense of deportment, and his son and Caddy both misrecognize the correlation between deportment as Turveydrop practices it and presence, a characterological bearing toward time, as exhibited by others.

Genuine deportment constitutes a mode of speech and manner that carries one away from oneself so as to connect to other personages and times. “Deportment”: the nominative form, as the OED says, of deport, a late 15th-century self-reflexive verb meaning “to behave (oneself),” derives from the 12th-century French verb déporter, whose provocative range of meanings includes to be patient, to dally and even to take one’s specifically sexual pleasure with. Deportment thus shares much with Nietzsche’s notion of slow and deep philology, with its pleasures in dallying. The word combines amusement with stability, remaining, delaying, and tarrying of the sort Sir Leicester does as his time declines. Such tarrying originates in the root word “portus,” for harbor, as in to harbor a feeling. And so deportment evokes not just a person’s manner, but also a tendency to hospitality, to protect, cheer, comfort, and console.

And yet the prefix “de” means “from” or “off” and with the Latin root word “portare,” “to carry,” this implies an attitude of detachment, impartiality, and impersonality, a coldness and superficiality. The subtle difference, if any, between comportment and deportment inheres in the direction of bearing, or carrying: deportment denominates an orientation away from oneself and to the public whereas comportment, while still a form of behavior, stresses one’s togetherness, integrity, or self-maintenance. Yet another philological detail, a tasteless joke, suggests that for Dickens’s milieu, deportment was decidedly physical: one of the fake book spines Dickens authored and ordered for his office at Gad’s Hill was “Miss Biffin on Deportment.” Miss Sarah Wight Biffin was a well-known painter born with no arms and only vestigial legs; she was 37” tall. Modern readers might also carry the connotation of reverse immigration, being deported from a country, but the “old lady of the censorious countenance” in the novel brings that up, too: “‘the father must be garnished and tricked out,’ said the old lady,” of Turveydrop, “‘because of his deportment. I’d deport him! Transport him would be better!” (Dickens 1977: 173). Transport, like deport, had the same double valence as a term of movement of people and goods as well as of feeling and disposition.

Aptly, then, Michel de Certeau invokes “countless tiny deportations” to describe walking, his paradigm for the everyday practices by which people exert their freedom and creativity as they actualize given places like the city into productive spaces of their own (1988: 103). For de Certeau, “The moving about that the city multiplies and concentrates makes the city itself an immense social experience of lacking a place—an experience that is, to be sure, broken up into countless tiny deportations (displacements and walks), compensated for by the relationships and intersections of these exoduses that intertwine and create an urban fabric” (1988: 103). Turveydrop caricatures not just a belated dandyism, then, but also personifies the way Dickens’s characters all inhabit spaces obliquely different, in temporality, ideology, and attention, from the places they occupy. Turveydrop’s deportment condenses and highlights the “countless tiny deportations” by which characters’ presence differs from the circumstantial present they inhabit. Given how de Certeau extends walking as a metaphor for reading, I want to suggest that these deportations, too, might model how a certain poststructuralist philology might license our freedom from the historical place given by the texts we read.

Despite his inanity, Turveydrop models the most telling function of deportment: he inspires belief. His wife “had, to the last, believed in him and had, on her death-bed, in the most moving terms, confided him to their son as one who had an inextinguishable claim upon him and whom he could never regard with too much pride and deference. The son, inheriting his mother’s belief, and having the deportment always before him, had lived and grown in the same faith … and looked up to him with veneration on the old imaginary pinnacle” (Dickens 1977: 173). The style of a text, at the level of diction but also of syntax, trope, and genre, constitutes its deportment or presence; it is the medium by which it moves readers to belief. Considering style as an index of what Steven Shapin calls “epistemological decorum,” the conventions recognized as guarantors of knowledge, we can not only see how Dickens’s world knew and felt in a traditional historicist sense, but also how we might reimagine how and what we can know and feel—how we are disposed toward the world. If we, as a profession, are to inhabit the past, then our deportment, our orientation to the present, cannot be like Turveydrop’s, a blind nostalgia, but instead ought to take up the likes of George and even Sir Leicester and, like Nietzsche, rearticulate alternative values as critiques of our imperfect present. While he values upheld by these odd bedfellows are unlikely to be the ones we uphold, their manifestation as a presence, as a tarrying against the stubborn often inhuman agencies of the present, is nevertheless moving. And it models, I think, how philology of a poststructuralist sort, however old-fashioned, might still translate our present concerns into past forms for a better and believable future.

References

Collins, Philip, ed. 1986. Dickens: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

De Certeau, Michel. 1988. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Randall. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Edited by George Ford and Sylvère Monod. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.

Hamilton, John T. 2013. Security: Politics, Humanity, and the Philology of Care. Princeton University Press.

Masson, David. 1875. British Novelists and their Styles: Being a Critical Sketch of the History of British Prose Fiction (1859). Boston: D. Lothrop and Co.

Nietzsche, Freidrich. 1997. Daybreak: Thoughts on the Prejudices of Morality. Edited by Maudemarie Clark and Brian Leiter; translated by R. J. Hollingdale. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Notes

[i] “Unaltered Terms” certainly has temporal parameters, and this scene generates enormous tension by moving slowly in the slow indoor space of the chapter while we know, outside its cozy confines Bucket and Esther chase Lady Dedlock for dear life in the snow and slush. The mutual deference George shares with Sir Leicester, toward whom he repeatedly, stiffly bows, likewise accompanies mutual nostalgic reveries: “The different times when they were both young men … and looked at one another down at Chesney Wold, arise before them both, and soften them both” (Dickens 1977: 697), Dickens writes. The residual manners of a bygone era mediate and soften an otherwise discomfiting present and even a terrifying future. Mrs. Rouncewell recognizes accordingly that Sir Leicester, in refusing candles and keeping the curtains open, “is striving to uphold the fiction with himself that it is not growing late” in more senses than one (Dickens 1977: 699): he is holding open hope for Lady Dedlock’s return but also for the survival of a system of manners, a disposition that favored him, to be sure, but which nevertheless also comforts George who craves the discipline that his friend Bagnet always claims to maintain with his wife, who’s clearly in charge. In rejecting his brother’s offer of employment or even partnership, George rejects the paradox Hegel ascribes to the bourgeois, who must work for another because work arises only from external constraint but who can only work for themselves because they have no masters. The passage personifies the tragic backwardness of Disraeli’s “Young England,” which imagined that recovering paternalistic, feudal values would somehow produce a different future, then, even as it also indulges in and valorizes the ethos of Disraeli’s practical historicism. George and Sir Leicester are comfortable in the past.

[ii] Bleak House introduces Sir Leicester in a way that seems to mock his mannerisms as contrived, pompous, and cold, but it emphasizes from the beginning their stability:

He is of a worthy presence, with his light-grey hair and whiskers, his fine shirt-frill, his pure-white waistcoat, and his blue coat with bright buttons always buttoned. He is ceremonious, stately, most polite on every occasion to my Lady, and holds her personal attractions in the highest estimation. His gallantry to my Lady, which has never changed since he courted her, is the one little touch of romantic fancy in him. (Dickens 1977: 12)

If this seems to fan the flames of the “dandyism” that pervades the novel’s world of religion, politics, law, and sociality, Dickens undercuts it immediately, “Indeed, he married her for love” (1977: 12).

CONTRIBUTOR’S NOTE

Jonathan Farina is Associate Professor of English at Seton Hall University. His book Everyday Words and the Character of Prose in Nineteenth-Century Britain is forthcoming from Cambridge UP.