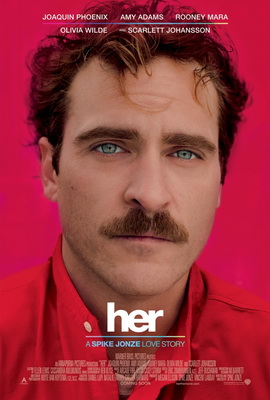

a review of Spike Jonze (dir.), Her (2013)

a review of Spike Jonze (dir.), Her (2013)

by Mike Bulajewski

~

I’m told by my sister, who is married to a French man, that the French don’t say “I love you”—or at least they don’t say it often. Perhaps they think the words are superfluous and it’s the behavior of the person you are in a relationship with tells you everything. Americans, on the other hand, say it to everyone—lovers, spouses, friends, parents, grandparents, children, pets—and as often as possible, as if quantity matters most. The declaration is also an event. For two people beginning a relationship, it marks a turning point and a new stage in the relationship.

If you aren’t American, you may not have realized that relationships have stages. In America, they do. It’s complicated. First there are the three main thresholds of commitment: Dating, Exclusive Dating, then of course Marriage. There are three lesser pre-Dating stages: Just Talking, Hooking Up and Friends with Benefits; and one minor stage between Dating and Exclusive called Pretty Much Exclusive. Within Dating, there are several minor substages: number of dates (often counted up to the third date) and increments of physical intimacy denoted according to the well-known baseball metaphor of first, second, third and home base.

There are also a number of rituals that indicate progress: updating of Facebook relationship statuses; leaving a toothbrush at each other’s houses; the aforementioned exchange of I-love-you’s; taking a vacation together; meeting the parents; exchange of house keys; and so on. When people, especially unmarried people talk about relationships, often the first questions are about these stages and rituals. In France the system is apparently much less codified. One convention not present in the United States is that romantic interest is signaled when a man invites a woman to go for a walk with him.

The point is two-fold: first, although Americans admire and often think of French culture as holding up a standard for what romance ought to be, Americans act nothing like the French in relationships and in fact know very little about how they work in France. Second and more importantly, in American culture love is widely understood as spontaneous and unpredictable, and yet there is also an opposite and often unacknowledged expectation that relationships follow well-defined rules and rituals.

This contradiction might explain the great public clamor over romance apps like Romantimatic and BroApp that automatically send your significant other romantic messages, either predefined or your own creation, at regular intervals—what philosopher of technology Evan Selinger calls (and not without justification) apps that outsource our humanity.

Reviewers of these apps were unanimous in their disapproval, disagreeing only on where to locate them on a spectrum between pretty bad and sociopathic. Among all the labor-saving apps and devices, why should this one in particular be singled out for opprobrium?

Perhaps one reason for the outcry is that they expose an uncomfortable truth about how easily romance can be automated. Something we believe is so intimate is revealed as routine and predictable. What does it say about our relationship needs that the right time to send a loving message to your significant other can be reduced to an algorithm?

The routinization of American relationships first struck me in the context of this little-known fact about how seldom French people say “I love you.” If you had to launch one of these romance apps in France, it wouldn’t be enough to just translate the prewritten phrases into French. You’d have to research French romantic relationships and discover what are the most common phrases—if there are any—and how frequently text messages are used for this purpose. It’s possible that French people are too unpredictable, or never use text messages for romantic purposes, so the app is just not feasible in France.

Romance is culturally determined. That American romance can be so easily automated reveals how standardized and even scheduled relationships already are. Selinger’s argument that automated romance undermines our humanity has some merit, but why stop with apps? Why not address the problem at a more fundamental level and critique the standardized courtship system that regulates romance. Doesn’t this also outsource our humanity?

The best-selling relationship advice book The 5 Love Languages claims that everyone understands one of five love “languages” and the key to a happy relationship for each partner to learn to express love in the correct language. Should we be surprised if the more technically minded among us concludes that the problem of love can be solved with technology? Why not try to determine the precise syntax and semantics of these love languages, and attempt to express them rigorously and unambiguously in the same way that computer languages and communications protocols are? Can love be reduced to grammar?

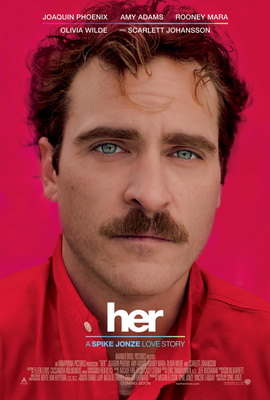

Spike Jonze’s Her (2013) tells the story of Theodore Twombly, a soon-to-be divorced writer who falls in love with Samantha, an AI operating system who far exceeds the abilities of today’s natural language assistants like Apple’s Siri or Microsoft’s Cortana. Samantha is not only hyper-intelligent, she’s also capable of laughter, telling jokes, picking up on subtle unspoken interpersonal cues, feeling and communicating her own emotions, and so on. Theodore falls in love with her, but there is no sense that their relationship is deficient because she’s not human. She is as emotionally expressive as any human partner, at least on film.

Theodore works for a company called BeautifulHandwrittenLetters.com as a professional Cyrano de Bergerac (or perhaps a human Romantimatic), ghostwriting heartfelt “handwritten” letters on behalf of this clients. It’s an ironic twist: Samantha is his simulated girlfriend, a role which he himself adopts at work by simulating the feelings of his clients. The film opens with Theodore at his desk at work, narrating a letter from a wife to her husband on the occasion of their 50th wedding anniversary. He is a master of the conventions of the love letter. Later in the film, his work is discovered by a literary agent, and he gets an offer to have book published of his best work.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CxahbnUCZxY&w=560&h=315]

But for all his (alleged) expertise as a romantic writer, Theodore is lonely, emotionally stunted, ambivalent towards the women in his life, and—at least before meeting Samantha—apparently incapable of maintaining relationships since he separated from his ex-wife Catherine. Highly sensitive, he is disturbed by encounters with women that go off the script: a phone sex encounter goes awry when the woman demands that he enact her bizarre fantasy of being choked with a dead cat; and on a date with a woman one night, she exposes a little too much vulnerability and drunkenly expresses her fear that he won’t call her. He abruptly and awkwardly ends the date.

Theodore wanders aimlessly through the high tech city as if it is empty. With headphones always on, he’s withdrawn, cocooned in a private sonic bubble. He interacts with his device through voice, asking it to play melancholy songs and skipping angry messages from his attorney demanding that he sign the divorce papers already. At times, he daydreams of happier times when he and his ex-wife were together and tells Samantha how much he liked being married. At first it seems that Catherine left him. We wonder if he withdrew from the pain of his heartbreak. But soon a different picture emerges. When they finally meet to sign the divorce papers over lunch, Catherine accuses him of not being able to handle her emotions and reveals that he tried to get her on Prozac. She says to him “I always felt like you wished I could just be a happy, light, everything’s great, bouncy L.A. wife. But that’s not me.”

So Theodore’s avoidance of real challenges and emotions in relationships turns out to be an ongoing problem—the cause, not the consequence, of his divorce. Starting a relationship with his operating systems Samantha is his latest retreat from reality—not from physical reality, but from the virtual reality of authentic intersubjective contact.

Unlike his other relationships, Samantha is perfectly customized to his needs. She speaks his “love language.” Today we personalize our operating system and fill out online dating profile specifying exactly what kind of person we’re looking for. When Theodore installs Samantha on his computer for the first time, the two operations are combined with a single question. The system asks him how he would describe his relationship with his mother. He begins to reply with psychological banalities about how she is insufficiently attuned to his needs, and it quickly stops him, already knowing what he’s about. And so do we.

That Theodore is selfish doesn’t mean that he is unfeeling, unkind, insensitive, conceited or uninterested in his new partners thoughts, feelings and goals. His selfishness is the kind that’s approved and even encouraged today, the ethically consistent selfishness that respects the right of others to be equally selfish. What he wants most of all is to be comfortable, to feel good, and that requires a partner who speaks his love language and nothing else, someone who says nothing that would veer off-script and reveal too many disturbing details. More precisely, Theodore wants someone who speaks what Lacan called empty speech: speech that obstructs the revelation of the subject’s traumatic desire.

Objectification is a traditional problem between men and women. Men reduce women to mere bodies or body parts that exist only for sexual gratification, treating them as sex objects rather than people. The dichotomy is between the physical as the domain of materiality, animality and sex on one hand, and the spiritual realm of subjectivity, personality, agency and the soul on the other. If objectification eliminates the soul, then Theodore engages in something like the opposite, a subjectification which eradicates the body. Samantha is just a personality.

Technology writer Nicholas Carr‘s new book The Glass Cage: Automation and Us (Norton, 2014) investigates the ways that automation and artificial intelligence dull our cognitive capacities. Her can be read as a speculative treatment of the same idea as it relates to emotion. What if the difficulty of relationships could be automated away? The film’s brilliant provocation is that it shows us a lonely, hollow world mediated through technology but nonetheless awash in sentimentality. It thwarts our expectations that algorithmically-generated emotion would be as stilted and artificial as today’s speech synthesizers. Samantha’s voice is warm, soulful, relatable and expressive. She’s real, and the feelings she triggers in Theodore are real.

But real feelings with real sensations can also be shallow. As Maria Bustillo notes, Theodore is an awful writer, at least by today’s standards. Here’s the kind of prose that wins him accolades from everyone around him:

I remember when I first started to fall in love with you like it was last night. Lying naked beside you in that tiny apartment, it suddenly hit me that I was part of this whole larger thing, just like our parents, and our parents’ parents. Before that I was just living my life like I knew everything, and suddenly this bright light hit me and woke me up. That light was you.

In spite of this, we’re led to believe that Theodore is some kind of literary genius. Various people in his life compliment him on his skill and the editor of the publishing company who wants to publish his work emails to tell him how moved he and his wife were when they read them. What kind of society would treat such pedestrian writing as unusual, profound or impressive? And what is the average person’s writing like if Theodore’s services are worth paying for?

Recall the cult favorite Idiocracy (2006) directed by Mike Judge, a science fiction satire set in a futuristic dystopia where anti-intellectualism is rampant and society has descended into stupidity. We can’t help but conclude that Her offers a glimpse into a society that has undergone a similar devolution into both emotional and literary idiocy.

_____

Mike Bulajewski (@mrteacup) is a user experience designer with a Master’s degree from University of Washington’s Human Centered Design and Engineering program. He writes about technology, psychoanalysis, philosophy, design, ideology & Slavoj Žižek at MrTeacup.org, where an earlier version of this review first appeared.

Back to the essay