by Pierre Joris

[presented as keynote address at the International Poetry Seminar

Moving Back and Forth between Poetry as/and Translation: Nomadic Travels and Travails with Alice Notley and Pierre Joris

on 7-8 November 2013, Université Libre de Bruxelles, convened by Franca Bellarsi & Peter Cockelbergh.]

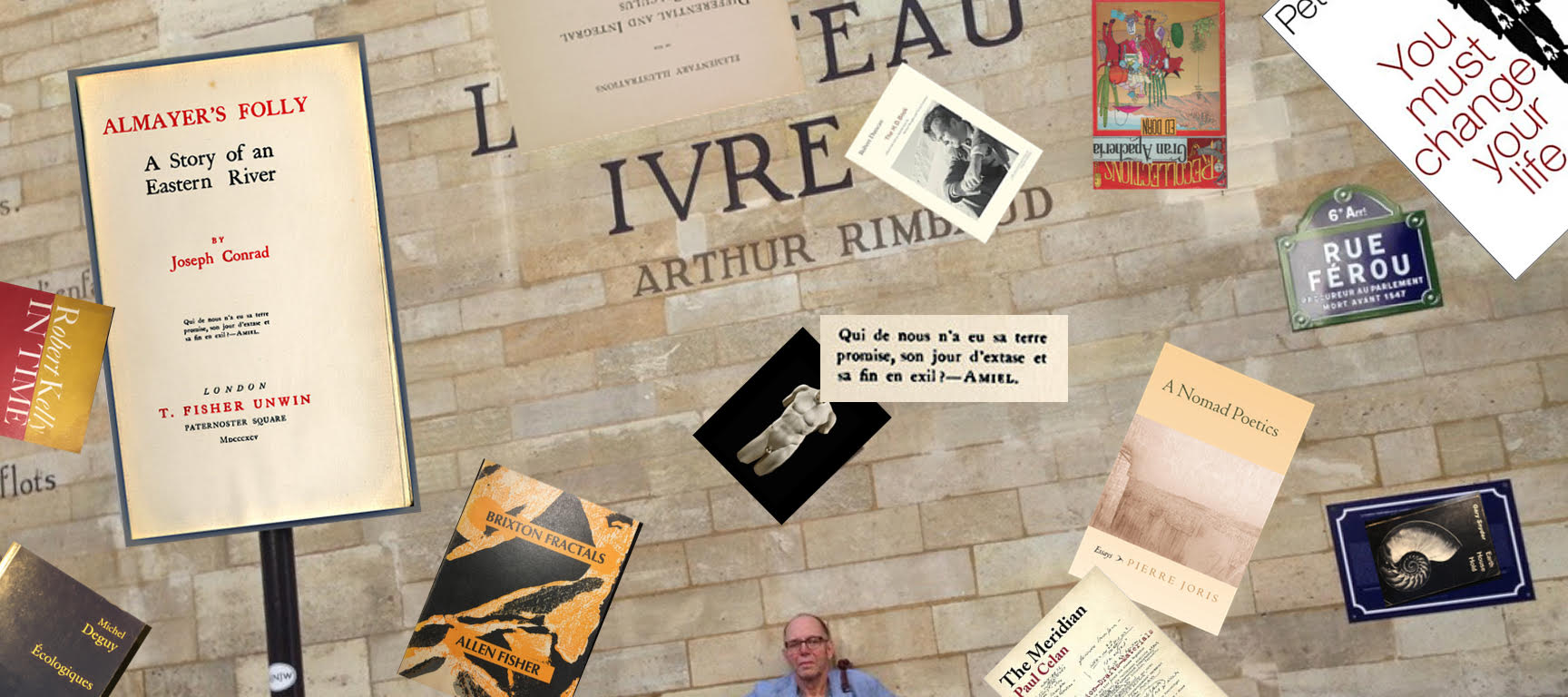

- “Who among us has not had his promised land, his day of ecstasy and his end in exile?” — signed: Amiel (with one “m” — the one with 2 “m”s will come in later). Thus begins or rather pre-begins Joseph Conrad’s novel Almayer’s Folly: A Story of an Eastern River (1895). The epigraph comes from Henri-Frédéric Amiel’s collection of poems & prose meditations Grains de Mil (Grains of Millet) (Paris 1854). This exergue stands at the head of, or, more accurately, stands before his first novel, thus before the vast oeuvre to come. Introïbo ad altarem Conradi.

The world-weary and wandering sailor from Poland I often confuse with my own grandfather, Joseph Joris, also a sailor, though in the early parts of his life & of the 20C when Conrad had already abandoned ship to take up the pen. Joseph Joris’ writings — mainly a large correspondence with major scientists & politicians of his era, or so my father told me, and some notations of which only one 3 by 4 scrap of astrological calculations remains — went up in flames during the Rundstedt offensive when his house in Ettelbruck, Luxembourg — living quarters plus confiserie fine plus the ineptly, for its time, named Cinéma de la Paix — was shelled & burned out by advancing US troops liberating us from the Germans. Joseph didn’t live to see this: he had died 2 years earlier from an infected throat — but that is another story.

So why do I begin here? Because this epigraph I came across a few days ago as I sat down to redact this “keynote” (more on that word in a minute) came into my mind — maybe because as I was thinking about what to say today I was looking out of my window, idly, and through the red & falling autumn leaves saw the flowing waters of the Narrows, where Hudson river and East river (tho not Conrad’s “Eastern River” — & yet?) mingle with the encroaching ocean in a daily tug-of-war, ebb & flood, riverrun riverrun — if I wanted to link elsewhere in modernism, but I don’t want to right now.

So, Conrad’s epigraph was suddenly there & I saw it not as something that stands before one book, but as something that stands before, above, in front of a whole oeuvre, a life’s work. A door all of a sudden — a gate, as in Kafka’s story. (Though Kafka, remember, couldn’t go to sea as my two Josephs did, but maybe he didn’t need to do so, for as he puts it in his Journals, he had the experience of being “seasick on firm land.”) This door or gate is not one to be waited in front of, as it is open & indeed meant for who is in front of it, & thus meant to be walked, strode through, though the crossing of this door’s threshold is something fierce & fearsome because as Amiel points out, the promised land is in the past. (“n’a pas eu…:” in the original, even if Ian Watt in his excellent comment on the novel translates — or uses someone’s version who translates this as — “who among us does not have a promised land…” present tense. Even Conrad in the 1895 first edition misquoted the lines from memory as “Le quel de nous n’a sa terre de promission, son jour d’extase et sa fin dans l’exil,” though he corrected it for the 1914 edition).

Thus: promised land in the past, while ecstasy may be back there too or in the present — let’s keep that ambiguity going & locate ecstasy also in the present day’s labor leading (after the promised land has long vanished) into the exilic future — through the gate, the door, the pre-text, that is the text — yes, I’ll own up to it — through writing, the act thereof. Writing is this exile, h.j.r, hejr, hejira, Hagar, she, me, wandering in desert or city, that nomadicity. I am certainly staying with that concept, or better, that process.

And so I’m home again, in the present-future (thus not the future perfect or futur antérieur of the French), no, in the present-future that is the tense of writing, an ecstatic-exilic tense. I am formulating it this way now & wouldn’t mind leaving it at that, but this is a keynote, so let me go there now.

- A note on “keynote,” and then a look at 10 years after. A keynote, says my wikipedia, “is a talk that establishes the main underlying theme… (&) lays the framework for the following programme of events or convention agenda; frequently the role of keynote speaker will include the role of convention moderator. (No way, Josè!) It will also flag up a larger idea – a literary story, an individual musical piece or event.” Okay, I’ve already told a “literary story,” & the events I’d like to flag are the poetry readings, which is where the work comes most alive for me. As to “an individual musical piece,” well, my love for etymologies immediately drove me to locate the origin of “keynote” in the practice of a cappella, often barbershop singers, & the playing of a single note before singing, that determines the key in which the song will be performed. I know that Ornette Coleman wrote & once told me face to face that “there is no wrong note,” but as I do not like the concept of one note setting the agenda, I will not play any such note; happily Alice Notley will also give a keynote, which will thus already make it at least two notes, maybe already a chord, & then I’ll leave the singing of many notes arranged in what they call music up to Nicole Peyrafitte later on in the program.

But I can’t resist to play a bit more with this notion of “key” — what does a key do, as it can do at least two things, something & its opposite, open or close? Of course at the beginning of an occasion the image will be of opening the proceedings, the door, maybe the gate mentioned earlier. And yet, a key does both open and close — maybe it does both at the same time! Who knows? My time is measured today, so let me just open-close this specific Pandora’s box via a poem by, you guessed it, Paul Celan:

WITH A VARIABLE KEY

With a variable key

you unlock the house, in it

drifts the snow of the unsaid.

Depending on the blood that gushes

from your eye or mouth or ear,

your key varies.

Varies your key so varies your word

that’s allowed to drift with the flakes.

Depending on the wind that pushes you away,

the snow cakes around the word.

So the word is there, variable, but needs to be spoken & I’ll take a further suggestion on how to go about this from Celan who writes:

Speak —

But do not separate the no from the yes.

Give your saying also meaning:

give it its shadow.

Give it enough shadow,

give it as much

as you know to be parceled out between

midnight and midday and midnight.

Look around:

see how alive it gets all around —

At death! Alive!

Speaks true, who speaks shadows.

- And so it is now “ten years after.” After what? One of the rock groups I liked in the 60s supposedly took that name from an event that had taken place ten years earlier, namely Elvis Presley’s breakthrough year of ’56. Lines from one of their songs still play in my mind from time to time: “Tax the rich, feed the poor / Till there are no rich no more.” And then the defeatist refrain: “I’d love to change the world / But I don’t know what to do / I’ll leave it up to you.” Has anything changed?

Ten years ago I published a volume of essays under the title A Nomad Poetics, core to which was the piece of writing called “Notes Toward a Nomad Poetics,” which — though the central concern had been with me even longer, much longer — I had started giving expression to even before 1993 & which had been published in an earlier form as a chapbook called Towards a Nomad Poetics by Allen Fisher’s Spanner Books. Note the tentative titles: “towards a…” & for the final version even just “Notes towards a Nomadic Poetics.” I said “piece of writing” purposefully just now, because one of the small misunderstandings regarding A Nomad Poetics I have encountered from time to time is that this piece of writing has been called a “manifesto” — with all the stern-brow seriousness & raised fist ardor the term suggests. I would like, 10 years after, to nuance this take a bit.

The manifesto, I’ve written elsewhere, is indeed one, if not the only new literary genre of the 20C, & I do draw on it to some extent — but I am very conscious of the fact that what I am trying to do is to write propositions for the 21C & to find a form that is both open & collaborative, that is culturally & politically critical, but not ideologically over-determined, as manifestos tend to be. It is neither an anonymous revolutionary pamphlet (as many of the Situationist manifestos were at a certain time), nor a synthetic piece with a number of signatures attached to it (from Marx & Engels, via the Surrealists, say, to the Manifeste des 120, for example, no matter how much I may like these). The proposition is different: it is a piece of writing I take full responsibility for, but to which I invite people to contribute — few have bothered to do so, though the 1993 text has at least the exemplary contribution of Brian Massumi, the excellent Deleuzian scholar & thinker.

But — & I can only briefly mention it in this context — the idea of collaboration has opened up since then in a different manner & place, namely as what Nicole Peyrafitte & I call “Domopoetics” & which finds its expression in performances that involve the two of us, in a combination of poetry, reflection (with it’s propositional moves, such as extensions of my rhizomatic moves & Nicole’s more “seepage” based processes), music & visuals, a project that also touches on something I will come to a bit later, ecology, be it as in Domopoetics, centered on the “household,” or in a wider in- & out-side sweep.

Now, in that core essay I do make “manifestish” moves, like the über-title, THE MILLENNIUM WILL BE NOMADIC OR IT WILL NOT BE, a détournement of a well-known citation leading back to Foucault & Deleuze; then there are the various definitions of concepts & the oracular pronouncements… but if you take these together with the willed heteroclite manner of the piece that ends with the (possibly incongruous) inclusion and commentary on a translation of a pre-Islamic ode, you may also note the tongue-in-cheek, not to say cheekiness of the collage (more dada than surrealist manifesto, playfulness is meant to trump, no not trump, that’s wargame talk, — is meant to poke fun at and possibly deflate dour revolutionary literary ardor). What I wanted was in fact to create a new genre, post-manifesto, something I did then call the “manifessay.” I don’t know if I succeeded beyond giving expression to my own poetics, i.e., if it, the form, has become available or is of any possible use beyond me. I’ll return to the notion of a new genre or of post-genre writing toward the end of this talk.

- I now want to address two or three points that I opened up but probably not enough in the 2003 manifessay, & that, it seems to me, need either clarification or extension. The first one of these arises from a quote by Muriel Rukeyser who writes: “The relations of poetry are, for our period, very close to the relations of science. It is not a matter of using the results of science, but of seeing that there is a meeting place between all the kinds of imagination. Poetry can provide that meeting place.” So, this notion that science & poetry can, have to connect, that, in fact, “open-field” poetry may be the ground where those two discourses can enrich each other. Unhappily that was the only occasion “science” came up in the 2003 version to which I had given the version number 4.0. In a 4.1 version I would insert more reflections concerning this matter, as it seems to me to be getting more & more urgent (see the next section). To begin with I would quote Robert Kelly’s take of:

a scientist of the whole

the Poet —

be aware from inside comes

the poet, scientist of totality,

specifically,

to whom all data whatsoever are of use,

world-scholar

Which means that all data not only can but should enter the arena of the poem. Each poet can of course only bring her own knowledges & experiences into that field — though the understanding that such a wide open field of possibilities does exist, right there in front of us, on the page or screen, with no restrictions imposed by pre-existing notions of form or content, an understanding that has to function as a major incentive & goad.

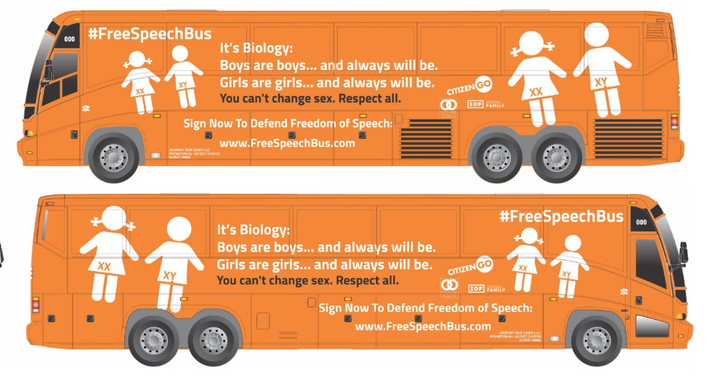

Scientific data as such, & in suspension with other information, would be central here as unhappily we have returned to an area where science is not only rightfully questioned for its excesses (in medicine, food-“science,” or its 19C underlying ideology of “progress,” etc.) but is also challenged in totally asinine but extremely dangerous ways by what may be the most disastrous unfolding event, namely the violent return of the religious (from the various US evangelical Christian fascisms to the Islamic totalitarianism of its Fundamentalist movements & beyond) & its denials of any scientific data, be that Darwinian evolution, the genetic egalitarianism of races, or what have you. This “return of the repressed” can however not be addressed by the same pious & self-righteous means used by positivist 19C determinism & traditional “atheistic” formulas.

An investigative poetics (& that is one mode of a nomadic poetics) addressing this problem could well start with thinking through the rather odd but useful book by Peter Sloterdijk, You Must Change Your Life (note that the title is a quote from a poem!). For example, one may have to rethink certain poetic practices after reflecting on the following from early on in the book, where Sloterdijk has been talking about Rilke’s poem “Archaic torso of Apollo:”

That this energized Apollo embodies a manifestation of Dionysus is indicated by the statement that the stone glistens ‘like wild beasts’ fur’: Rilke had read his Nietzsche. Here we encounter the second micro-religious or proto-musical module: the notorious ‘this stands for that,’ ‘the one appears in the other’ or ‘the deep layer is present in the surface‘ — figures without which no religious discourse would ever have come about. They tell us that religiosity is a form of hermeneutical flexibility and can be trained.

Unhappily there have been rather few poets who have worked along those lines, i.e. bringing scientific discourse into the field of poetry to test & extend its possibilities. Of my generation, except for the use of scientific, mainly mathematical concepts in formal decisions, such as the great oeuvre of Jackson MacLow, or the OULIPO poets or, say, Inger Christensen or Ron Silliman using the Fibonacci series as formal compositional procedures, I can only think of two poets deeply involved in that way & bringing actual scientific data into the work: Allen Fisher & Christopher Dewdney. The latter has put his relation to science very clearly. “My poetry,” he says, “is warped out of science. I think I’m a frustrated scientist in poetry and a frustrated poet in science. A lot of poets have an anti-science bias, a vision of themselves as romantics in a tower, but I don’t. I’m a naturalist, I believe that science and nature are one, that science is a perceptual tool which allows us to define nature more specifically. Science has to incorporate and mythologize as it happens. All poetry deals with information, finally.”

Concerning Allen Fisher, I did say enough, I believe, in version 4.00, but let me re-quote a bit from his Introduction of Brixton Fractals::

Imagination and action. My knowledge of the world exists validly only in the moment when I am transforming it. In this moment, in action, the imagination functions, unblocks passivity, refuses an overview. Discontinuities, wave breaks, cell divisions, collapsed structures, boundaries between tissue kinds: where inner workings are unknown, the only reliable participations are imaginative. The complex of state and control variables. The number of configurations depends on the latter: properties typical of cusp catastrophes: sudden jumps; hysteresis; divergence; inaccessibility. Boiling water’s phase change where the potential is the same as condensing steam. Random motion of particles in phase space allows a process to find a minimum potential. What is this all about? It’s a matter of rage and fear, where the moving grass or built suburbia frontier is a wave prison; where depth perception reverses; caged flight. With ambiguous vases it’s as if part of the brain is unable to reach a firm conclusion and passes alternatives along for a decision on other grounds. The goblet-and-face contour moves as it forms in your seeing.

The result of which is a poetry of use, though the uses be not your usual aesthetic jouissance and/or socio-political alibis:

Brixton Fractals provides a technique of memory and perception analysis. It can be used to sharpen out-of-focus photographs; to make maps of the radio sky; to generate images from human energy; to calculate spectra; to reconstruct densities; to provide probability factors from local depression climates. It becomes applicable to reading; to estimate a vector of survival from seriously incomplete or hidden data, and select the different structures needed. It can provide a participatory invention different from that which most persists.

Among a younger generation, I fear I have not come across much work incorporating the discourse of science. This may be my own lack, the fact that I can no longer keep up with the incredible avalanche of poetry coming down on us. But I do want to mention at least one of the younger poets, namely James Belflower, who after a brilliant first book, Commuter, has just published a second book The Posture of Contour, rich in exactly those materials & thinking involving science & scientific discourse. This is excellent explorative work that is truly experimental without being gimmicky or surface “avant-gardist.” Belflower, by the way, is also presently at work on a translation of a book by our next presenter, Jan Baetens’s rewriting of a Jean-Luc Godard’s script, for which he has also corralled Peter Cockelbergh help. But let me move on.

- The one word or concept I now see as most grievously underdeveloped is that of ecology. I do think of it as present in version 4.00, however, in that it is inherent if unspoken in the vision of a nomadic figure: the nomad’s life is based on a clear and sharp perception and discrimination of environmental factures. (I had first written “fractures” — which might be the right word). For the desert inhabitant it is of course a matter of survival. In the same way nomadic art is an eminently environment-conscious art: portable, spare, it clings to or arises from the everyday objects of perusal: embroidered & engraved saddles or bridles, painted portable utensils or inscribed, i.e. tattooed parts of the body; the core elements of the dwelling: rugs and carpets — all these are pure expressions of art, & the most formal and richest artifact is also the lightest as behoves a continuous traveler: the poem, no matter it’s size or weight, carried in mind or, as they say, by heart. A nomadic poetry was thus, for me, an obviously highly environment-conscious art.

My own sense of the ecological question goes back to the late sixties and, in poetry, the discovery of Gary Snyder’s work as poet and essayist. It was clear back then already that environmental problems needed to be thought & written about, & indeed they were, even if as yet mainly or only in the underground press, & entered into one’s daily practice in terms of food (first organic food movements, macrobiotic diets & restaurants, etc.) clothing, and as a political direction to be incorporated into any progressive ideology.

But it is now clear, “ideology” or rather ideology-critique, though necessary, also became a hindrance later on. During those years (70s into 90s) of the “postmodern”, that stance entailed the deconstruction of what Jean-François Lyotard & others called the “grand narratives,” from Christianity to Communism, i.e. all single-centered soteriological utopian systems. The fervent yet cool-headed desire was: never again such eschatological, transcendental movements in the pursuance of whose aims all means are justified and thus all crimes permissible, from the grand medieval inquisitions to the Stalinist & Nazi exterminations. Politics, we now thought, have to become local, momentary, situationist, etc. What Félix Guattari & others called Micropolitics. Under this premise, one angle, one line of flight, one momentary territorialization of our space would be or could concern itself with the environmental problem.

I’m putting all this very schematically as I don’t have the time to develop it in detail, but it now seems clear to me that the time has come to make ecology (oeco-logos, the logic of the house, of our house earth, of our earth-house-hold, to use Snyder’s term), to make ecology the engine of a new grand narrative. Such a grand narrative would differ from the old ones (& thus hopefully avoid the disasters provoked by human hubris that thought of this world as, or tried to force it into a scheme of the anthropocentric). It would not be anthropocentric, human-centered (as the Christian or Communist one were) but anchored, or come from, outside the human sphere, the earth, & thus restate, refocus, the human in relation to the world it lives in. A world in a new age, an age that has come to be called the “anthropocene” to point to the overwhelming influence human actions now have on the earth. A non-transcendental, immanentist situation that does not have future perfection (paradise in heaven or on earth) as its aim but survival of life in all its rich & diverse forms (with the human only one such, and important only as the major danger to survival) in the contingent environment of this planet. Which also entails, despite the fact that the name of us, “anthropos” now glows radioactively in the age’s name, to start from the realization that homo sapiens (that misnomer!) is not outside, beyond creation; there is not a “nature” outside or surrounding us nature is us & the rest, the world with us included. “Nature” is everywhere, as Spinoza said of god.

One way into this would be through a book I’d like to draw your attention to, namely Michel Deguy’s Écologiques, the quatrième de couverture of which states: “Geocide is in process; not “a” geocide, but “the geocide:” there will not be two. Ecology, a ‘logie’ [thought, word, saying] of the oikos [house, dwelling, terre des hommes] is not optional. If it is not radical, it is nothing.” This book, a series of small essays, notations, reflections, he himself calls it “a sort of witnessing,” is also formally fascinating in that the urgency & radicalness demanded eschew the scriptural “manifesto” form of the old grand narratives, but belongs exactly to the extrême contemporain in its assemblage form (& contains reflections on that form). Here are a few hints (in my translation):

Another romantic leitmotiv, and thus to be transposed for us, come down to us from Hölderlin through Heidegerrian conduit — can it help — for a long time translated as “What remains is what the poets create.” [“Was bleibet aber stiften die Dichter”] and that our era (this mutation of “the crisis,” if you want) forces us to read thus: “the remains, art plays them again.” Even better to understand it thus: the remains we are left with, the relics, is it possible that the artists, those who work in language, philosophers and writers together with all those who work in other “arts,” including those that technique has added, will relaunch them. …Is a last chance called ecology?

The poet Edward Dorn pointed out some few years back that one of our problems is that “we do not even yet / know what a crisis is.” Interestingly, Deguy in this books develops a notion of “crisis” that may answer Dorn’s slight, when he writes “this exercise in thinking (this ‘experience in thought’) has to rise to ‘its last consequences,’ in its hyperbolic paradoxical amplification,” where it will risk this: “…what is called the crisis offers the chance of a parabolic ‘rebroussement,’ a parabolic turning back. [Note that “rebroussement” is a term also used in geology where it means the ‘Torsion localisée des couches, due au frottement le long d’un contact anormal et montrant le sens du mouvement /torsion localized in the strata, caused by friction along an anormal contact and showing the direction of the movement/’ (Fouc.-Raoult Géol. 1980). Further in math it refers to the point where a curve changes direction; you also speak of an ‘Arête de rebroussement.’”

How to translate this last phrase? “Arête” immediately rhymes for me with the Greek “arete” — & I’ll come to that soon enough. But interesting to note how problematic the translation from natural language to another, French to English here, a concept in mathematics, a so-called “universal” language can be. As a footnote on page 435 of Augustus de Morgan’s The Differential and Integral Calculus puts it:

One sound writer on this subject (and perhaps more) has attempted to translate the words arête de rebroussement into English by edge of regression, which seems to me a closer imitation of the words than of the meaning. Many words might be suggested, such as the ligature of the normals, or their osculatrix, or their omnitangential curve. Also with reference to the developable surface, the arête, &c. might be called the generatrix, or the curve of greatest density, &c.

Deguy concludes by defining it as “la ligne formée par les points d’intersection des génératrices rectilignes consécutives de la surface / the line formed by the intersection points of successive rectilinear generatrices of the surface.”

So Deguy’s rebroussement is not a simple turning back on itself, not a return to the past, but another, a further, torque. He goes on: “A politician is someone who cannot understand, admit, that the crisis, from Hesiod to Husserl, from Sophocles to Valéry, names historicity itself. It is crisis forever. The ‘solution’ of the crisis is a new critical phase, of sharing — of the relation in general, of societies among themselves, of one society in relation to itself, of one subject to himself.”

Deguy sees three movements in the overcoming, the coming out of the crisis: “an uprising, a revolution, reforms.” Which he then calls “by one of its great names, utopia.” And to suggest that “précisément l’utopie aujourd’hui, c’est l’écologie. / Utopia today is precisely ecology. There is no other one.” Fascinating too, how Deguy begins usefully to think through other rebarbative aspects of our relation to world. He thus suggests that “ecology does not concern the environment, literally what environs, what surrounds, (the “Umwelt” of the ethnologues) but the “world” (the “Welt” of the thinkers). It is the difference between those two that needs to be rethought from the bottom up, he suggests, because of the profound oblivion into which the world and its things (les choses), or “the oecumene” have fallen. Thus globalisation (in French la “mondialisation”) would be in truth an end of or to “le monde,” the world, a loss of world, because “the world worlds in things and its ‘worlding’ has to be entrusted not to technoscience, but to the philosophers and the artists — to all the humans in the arts (les hommes de l’art), and, specifically to the poetics of the works.”

These formulations not only show the importance of Deguy’s writings in Ecologiques and thus the need for its translation — but also the difficulty this translation entails given the nomadicity between his philosophical logos & the poetics, which you can glimpse in the needed and relished neologisms above. And now, beginning to run out of time, let me turn to certain questions in regard to translation that have been haunting me since the publication of version 4.00 of the manifessay.

- And thus to the second Ammiel — but this one with two m’s — I mean Ammiel Alcalay and some parallel thinking we have been doing on the subject of translation. In the Nomad Poetics manifesto, the work of translation is only liminally mentioned when in fact it has been central to my endeavors from the beginning — though obviously it gets more thought & analysis in other essays in the Nomad Poetics volume. What I would like to add in a putative 4.1 version (why putative? — this is that version, probably) is an exploration of the limits of translation.

Why limits? A strange term to use for someone who has always equated translation & writing itself, who has claimed (& stays with this claim) that all writing is translation & that therefore the traditional differences between the two have to be abolished as they are false “class” barriers. Over the last 10 years, I have been involved in two major but very different translation projects: first, the translation of the historico-critical edition of Paul Celan’s The Meridian, a volume that gathers all the various drafts, versions, notes, scraps, letters, even a radio-play, with all the (carefully reproduced) strike-outs, inserts, marginal marks & so on, that we have between the moment Celan was informed that he had been given the Georg Büchner prize and the date on which he had to give his acceptance speech. The original editors, Bernard Böschenstein and Heino Schmull did an incredible job gathering these materials & devising a book structure to contain them. If I have one doubt about the book, it is this one: the book opens with the 18-page essay in its final, definite form, then proceeds backwards through the various drafts to the earliest scrap of paper. This makes for a very attractive book, though I now wonder if it wouldn’t have been more instructive to build the volume in the genetic sense, i.e. from the first idea to the final essay, so that a reader would be able to witness the creation of context & text in its / as a historical process. Be that as it may, the essential thing this translation taught me was the importance for a deeper textual understanding of involvement with and thus knowledge of its contexts, its process.

During the years I put together Poems for Millennium vol 4: The UCP book of North African Literature, or Diwan Ifrikiya as I prefer to call it, the question of how to present over 2000 years of a literature to a major part unknown to Western readers (I first wrote “raiders” — which is also an accurate way of describing what the West did & still does to the Maghreb), that question came up, of course. Happily the “grand collage” format elaborated by Jerome Rothenberg & myself in the early volumes of the Poems for the Millennium series — chronological galleries, thematic “books,” individual commentaries, intros to all the sections, etc. — allowed for a presentation of actual contextual matters, from maps to alphabets, from images to amulets, that serve as a matrix for the poems. For example, the second diwan, El Adab or the invention of prose, endeavors to gather texts from historical literary treatises, history & geography manuals, philosophical meditations, erotic manuals etc.

Despite what I think of as a rather successful if incomplete handling of these matters of context, I do agree with Ammiel Alcalay when he writes, after bringing up such different events as 9/11 & the ensuing sudden interest in Arab matters & translating from that language, followed by the Iraq war & the ‘official’ writing that has ensued from that catastrophe:

How are those of us involved in transference and translation to respond to such circumstances? What is our role in the politics of imagination and transmission? Have we reached a point where NOT translating, providing access to, handing down works from the Arab world might be more legitimate? When we decide to participate, how do we insulate and protect such works and ourselves, not merely from assimilation, but from collaboration… Writers and translators often wind up playing someone else’s game, and become complicit, perpetuating the same rules with new players.

Which leads Alcalay to conclude that no act of transmission is innocent and therefore demands utmost vigilance, a kind of vigilance, he goes on, “that recognizes, as the American poet Jack Spicer once put it, that ‘there are bosses in poetry as well as in the industrial empire.” As writers, translators, commentators in the area of what Michel Deguy called “le culturel,” — to be differentiated from “la culture,” but inescapable as the sphere in which we as ‘travailleurs du symbolique’ labor today — we have to be aware that, for example, translating a major novel by a third world author wrenches that work out of its natural habitat, plops it into an environment where it can only be read according to the latter’s rules (say, Kateb Yacine’s Nedjma, in relation to William Faulkner’s narrative universe, etc.) Or, more viciously as in the case of my translation of Abdelwahab Meddeb’s essay THE MALDAY OF ISLAM which was nearly hijacked by DC rightwing think tank people when Daniel Pipes asked the NY publisher for first serialization rights and the right to “subedit” the extracts — I managed to fight this off after investigating who those people were.

So, there is also a need, a duty to provide contextual materials, to try to change the very framework of the translation activity, so that the act of translating can be “an act, a way of erecting a picket line against the bosses, to reclaim some part of our suppressed and isolated humanity and participate in it in new ways.” Alcalay concludes that “ to protect against assimilation and collaboration requires more than fitting newly introduced and revived texts into existing frameworks. Defining what information is for us, where it comes from, and where to find it becomes an essential survival kit.”

Thus part of such a watchful & critical process of translation is also what I like to call an ‘investigative nomad poetics,’ because ideological cons can go so far as to actually corrupt the very language. Take the example of the so-called “Confucius Institutes” which are under the supervision of the Chinese Language Council International (known as Hanban). These Institutes teach Chinese language and culture after setting up shop in Universities in the West. I’m drawing on an excellent investigative article by Marshall Sahlins that appeared in this week’s Nation. Hanban is an instrument of the PRC’s party apparatus operating as an international pedagogical organization. This means that its agreements with the foreign, including many American, institutions of higher learning, include non-disclosure clauses, making the terms of the agreement secret. US universities sign on to this— which is most likely totally illegal under US law — eager as they are to get an all-paid for “Confucius Institute” & the ensuing prestige. Besides such basic no-nos as being prohibited to mention the Tiannamen Square massacre, or Tibet, the Dalai Lama, or human rights, etc. the actual core problem, if you look closer, are the language teaching methods, in fact the very language taught. This looks innocent enough according to the bylaws, which state: “The Confucius Institutes conduct Chinese language instructions in Mandarin using Standard Chinese characters.” But, as Sahlin details, this is the “simplified script officially promulgated by the PRC as a more easily learned alternative…” This means that what is available in this script & thus what the CI students are taught to read are only those texts or revised texts the PRC allows you to read & has prepared & altered, and thus for example no Chinese texts from other parts of the world, Taiwan, or even Hong-Kong can be deciphered by people trained in the CI’s! Totalitarian censorship effected via creating & imposing a new language allowing for the rewriting of all cultural documents…

- Finally, I’d like to speak to my current practice: what I want to do from now on is continue to some extent with nomadizing my writing as much as nomadizing in my writing, while moving toward some new trajectories, other complex meandering orbitals. You see, when I sit down & let the process of writing happen, it tends to come out as a recognizable “poem,” & I am by now somewhat bored by this. Ah, I say to myself, here’s another poem — couldn’t it be some another critter, somealien, unknown form? I guess the familiarity of recognizing the poem under hand has some comforting sides (it is comforting to recognize your own face in the mirror when you get up in the morning), & I enjoy detecting a new move, or rhythm or color or line or sound in the poem-matrix, and yet, and yet. (Thinking here of a poet I admire tremendously, John Ashbery, whose production into old age — John is 86 — has gone unabated, but whose yearly new volume seems to me to have the same poem rearranged again & again, a tremendous life-long flow, flood, or maybe better ribbon of writing Ashbery snips off bits to make into books & cuts those into smaller bits to make poems — it’s tremendous & astounding & a true feat, but I have to confess that my pleasure in the work by now has become mainly aesthetic recognition rather than discovery of anything new, thought, rhythm, music, form — or maybe better, it is absolutely wonderful comfort food I can cuddle up with in my armchair when the umpteenth rerun of my fav TV series, Law & Order, is too boring. And comfort is something we absolutely need in our lives, for sure. But.)

A more serious reason to escape “the poem” (between quotation marks) is something I have to plead guilty to, that Frankenstein monster called “creative writing” which for part of my life provided the income that permitted me to read & write. But in the US we now create something like 3 to 6000 professional diploma’ed “poets” a year who are turning out hundreds of thousand “poems” day in day out — there are now at rough glance something close to half a million published poets in the US. Now, I prefer that to be the case rather than those kids having wandered off & joined the military or the evangelical troops. At the risk of sounding elitist, I want to suggest however that most of this work does not have what my third grandfather of the day, grand-pa Ezra called the “arete,” which he translated as “virtue”, though for the Greeks the word actually probably meant something closer to “being the best you can be”, or “reaching your highest human potential”, & which I like to mistranslate further as “arête,” as in a French fish, though not as a French stop sign, or, better even, as the arresting quality of something with spine.

So, what do I want? In my notebooks I found this entry, as I was preparing to envisage the writing to be done now, after I stopped teaching, & with several major projects out of the way:

“…write something that is unrecognizable as a poem, write ‘books’ [never a, one, book, always the plural] but so that they are not beholden to that late 19C form of the book so elegantly proclaimed by Mallarmé & taken up under various guises by the 20C avant-garde. This here now is the 21C. Everything — pace Mallarmé — is not meant to end up in a book, even if as we screw up the planet more & more everything that will be left of us may end up in a book if one as heat resistant as the new climate requires can be devised, once we have become extinct on this gone planet veering from blue to red. No. The books or the writing I envisage are open books that have their prolongations, their links, within the ever more tenuous world that surrounds us, but not a writing that mimetically reflects the outside (which would only increase the heat by mirror-effect & in the cave of this non-platonic book we cannot have fires heating up) but one that proposes a range of coolants —”

To put it another way, work seems to leak — out of the book and into the world, and from the world into the book. Nicole Peyrafitte’s notion of “seepage” (see her recent writings in her book bi-valve ) enters here to play with & off & extend the rhizomes & lines of flight of my nomadics. What is at stake here is circulation: of reading that turns into writing and vice-versa, but also of people, of words, of love, of blood — printer’s bleed but also terrorists’ victims’ blood, terrorists everywhere, from the US Congress & my gun-crazed co-citoyens, to the mad mujahiddin of Daech & AQIM. These books of multiple narratives & troubled typographies, which “may be incompletely / confused” (as the young poet James Belflower puts it), asks you to be a (not so innocent) active performer as much as a reader. Take the risk —

How to come to this writing beyond genre is of course the question I have been groping with for some time now. I can only start from what I know, i.e. from the grand-collage century I come from, some specific realizations of that century, those for example I have spent years gathering with Jerome Rothenberg & Habib Tengour in our Millennium anthologies, others too. Here is a 20C quote to go forth with into our already quite entamé (nicked, gouged out, gored, gashed, i.e. wounded) 21C. It is a quote you will know as it is well-known, often used, that I would like to put again at the head of any such new writings, thus as an epigraph here, to bring to a close the keynote that started with a 19C epigraph that led into our 20C. It comes from Robert Duncan’s HD Book, from the chapter “Rites of Participation,” a chapter that begins “The drama of our time is the coming of all men (and women) into one fate, ‘the dream of everyone, everywhere.’” First published in Caterpillar # 1 in fall of 1967 (a month after I first set foot on the American continent) it was written a few years earlier, I believe, so dates from the mid-sixties. Half a century later it holds a more ominous, less optimistic note, given the ecologistic aspects of the new grand narrative of that “single fate.” But here is the quote I was thinking of exactly, which happens a page or so later in Duncan’s ‘book,’ after he has been talking about Plato’s Symposium:

The Symposium of Plato was restricted to a community of Athenians, gathered in the common creation of an arete [ah, that word again!], an aristocracy of spirit, inspired by the homoEros, taking its stand against lower or foreign orders, not only of men but of nature itself. The intense yearning, the desire for something else, of which we too have only a dark and doubtful presentiment, remains, but our arete, our ideal of vital being [ah! there’s another good definition!], rises not in our identification in a hierarchy of higher forms but in our identification with the universe. To compose such a symposium of the whole, such a totality, all the old excluded orders must be included. The female, the proletariat, the foreign; the animal and vegetative; the unconscious and the unknown; the criminal and failure — all that had been outcast and vagabond must return to be admitted in the creation of what we consider we are.

I would only like to add to Duncan’s list the orders of geology and water & air, and to amend ever so slightly the last sentence to read: “all that had been outcast and vagabond must be joined by us out there to help in the nomadic creation of what we consider we are.”

SOURCES

Conrad, Joseph. Almayer’s Folly: A Story of an Eastern River (T. Fisher Unwin, London 1895).

Amiel, Henri-Frédéric. Grains de Mil (Joël Cherbuliez, libraire-éditeur, Paris 1854).

Watt, Ian. Conrad in the Nineteenth Century. Vol. 1, footnote #6 p.66 (University of California Press, 1979.

Celan, Paul. “With a Variable Key” & “Speak, You Too,” in Paul Celan, Selections, edited by Pierre Joris, p. 51 & 54. (University of California Press, 2005.)

_________. The Meridian. Final Version—Drafts—Materials. Translated by Pierre Joris. (Stanford University Press, 2011)

Joris, Pierre. A Nomad Poetics (Wesleyan University Press, 2003.)

_________, editor (with Habib Tengour). The University of California Book of North African Literature (vol. 4 in the Poems for the Millennium series, UCP, November 2012)

Rukeyser, Muriel. The Life of Poetry. p. XI (Ashfield, Mass. Paris Press 1996.)

Kelly, Robert. In Time, p. 25 (Frontier Press, 1971)

Sloterdijk, Peter. You Must Change Your Life (Polity, 2014)

Fisher, Allen. Brixton Fractals. (Aloes Books, London 1985)

Belflower, James. The Posture of Contour. (Springgun Press, 2013)

Deguy, Michel. Écologiques, p.23. (Hermann, Editeur, 2012)

Dorn, Edward, Recollections of Gran Apachería, n.p. (Turtle island Foundation, 1974)

De Morgan, Augustus. The Differential and Integral Calculus. (Baldwin and Cradock, London, 1842)

Alcalay, Ammiel. “Politics & Translation,” in: towards a foreign likeness bent : translation, durationpress.com e-books series. http://www.durationpress.com, n.d.

Sahlins, Marshall. China U. Confucius Institutes censor political discussion and restrain the free exchange of ideas. The Nation, October 30, 2013 https://www.thenation.com/article/china-u/

Snyder, Gary. Earth House Hold. (New Directions, 1969)

Lyotard, Jean-François. The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. (University Of Minnesota Press, 1984.)

Guattari, Félix & Deleuze, Gilles. Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. (University of Minnesota Press, 1987)

Meddeb, Abdelwahab. The Malady of Islam. Translated by Pierre Joris. ( Basic Books,2003.)

Peyrafitte, Nicole. Bi-Valve: Vulvic Space / Vulvic Knowledge. (Stockport Flats, 2013).

Duncan, Robert. The H.D. Book. (University of California Press, 2011.)

The Financial Turn

The Financial Turn