by Christian Haines

This essay was peer-reviewed by the editorial board of b2o: an online journal.

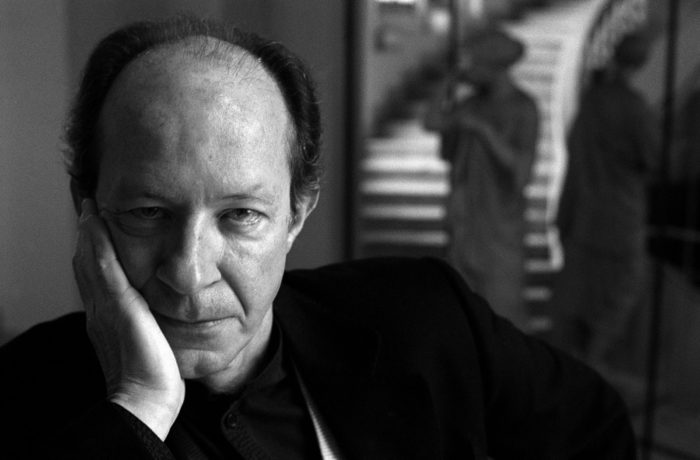

In Stanzas: Word and Phantasm in Western Culture, Giorgio Agamben diagnoses the constitutive tragedy of modernity as a rupture between thought and poetry. He elaborates this tragedy as “the scission of the word,” a strife that means that “poetry possesses its object without knowing it while philosophy knows its object without posessing it” (xvii). This scission gives birth to criticism, understood as that genre of thinking and writing whose intimacy with its object always suffers from an essential foreignness. Criticism, Agamben writes, is “born at the moment when the scission reaches its extreme point. It is situated where, in Western culture, the word comes unglued from itself; and it points, on the near or far side of that separation, toward a unitary status for the utterance” (ibid.). The cliché that every critic is a failed writer, a scribbled poem tucked in the back of her desk drawer, owes its existence to a certain truth, namely, that criticism includes an aspiration to become its object, or at least to borrow some of its potential, to include within criticism a space in which the enjoyment of poetry takes place. Criticism, then, is neither poetry nor philosophy, for as Agamben explains, “To appropriation without consciousness [poetry] and to consciousness without enjoyment [philosophy] criticism opposes the enjoyment of what cannot be possessed and the possession of what cannot be enjoyed. […] What is secluded in the stanza of criticism is nothing, but this nothing safeguards unappropriability as its most precious possession” (Ibid.). Stanzas consists of a series of essays in which philosophy becomes acquainted with criticism, formulating the concept of this inappropriability, thinking along with criticism’s encounters with poetry. For Agamben, these encounters rehearse the “original fracture of presence,” the scission of the word, the division of essence from appearance – in short, the history of metaphysics. At the same time, the encounter with the poem, the practice of criticism, offers a gift irreducible to metaphysics. It offers the promise of “an area from which the step-backward-beyond of metaphysics […] becomes really possible,” an “intuition of what might be a presence restored to the simplicity of this ‘invisible harmony’ [between being and thought]: the last Western philosopher [Agamben means Heidegger] recognized a hint of this harmony in a painting by Cézanne in the possible rediscovered community of thought and poetry” (157). According to this logic, criticism does not enjoy the reconciliation of poetry and thought, instead it enjoys the coming of a community between them, the anticipation of a word undivided from itself.

Agamben’s entire philosophical project is dedicated to this potential reunion between poetry and thought. It lets itself be guided by this horizon in much the same way a ship’s captain sets her course by the glimmering light of the North Star. In this essay, I argue that this orientation speaks to the power of Agamben’s thinking of the political but also to its fundamental limitations. For, as I explain below, Agamben makes the test of politics its approximation of this reunion: he tasks politics with the mission of bringing thought and the cosmos back together again, and, in doing so, he measures the authenticity of politics by the degree to which it embodies a poetry of thought. In other words, it is not merely philosophy that finds its redemption in poetry but also politics. This chiasmic traffic between ontological spheres (between aesthetics and philosophy, politics and philosophy, politics and aesthetics) is extremely fruitful in a sense, reviving an existentialism in which life is wagered on its capacity to think its situation, and in which this capacity in turn depends on a commitment to politics. At the same time, this renewal of existentialism comes at the cost of historicity, on the one hand, and sociality, on the other. It reduces history to a meta-narrative – a prolonged oscillation between metaphysical terms, with the occasional glimpse of apocalypse or the coming messiah – and it formulates politics as if it were so many permutations of a single paradigm (sovereignty). In doing so, Agamben leaves those who would think alongside him stranded in a position where political action is adequate to the situation only insofar as it overcomes society and history, only insofar as it leaps into a messianic night in which all cows (as Hegel once put it) are black.

This essay is not exhaustive in its assessment of Agamben’s political thought, though it aims for a certain comprehensiveness. I focus on the Homo Sacer project, the series of books beginning with Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life and concluding with The Use of Bodies.[i] I devote most of my attention to The Use of Bodies for two reasons: first, because of its sheer ambition, its desire to do nothing less than refound both ontology and politics, the latter on the basis of the former; and, second, because of the book’s status as a conclusion. This second point deserves elaboration, since the risk of describing a project in terms of its conclusion is that one may not only miss a number of interesting detours but also that one may ignore certain premises, skip over corollaries, and confuse the meaning of the whole with one of its parts. I do sometimes weave in discussions of the preceding volumes, yet this has less to do with making sure to account for every step in Agamben’s argument – a task too large for a single essay – than with tracking the recursive structure of the series, which deploys tropes, motifs, and conceptual maneuvers in a looping spiral. When Agamben introduces a concept, it is almost always a variation on another concept, the couplet of bare life and sovereignty, for instance, mutating into a herd of distinct and yet related philosophical creatures: the ban, the state of exception, etc. More importantly, however, Agamben’s conclusion should be taken so seriously because of Agamben’s own investment in endings. Over and over again, Agamben articulates the truth of a concept, a paradigm, or a practice in terms of its extreme conclusion or absolute limit. The spiral of conceptual repetition and variation gives way to messianic interruption, a suspension of linear time or chronology, an expansion of the fleeting instant/opportunity (kairos) into the Day of Judgment. In The Use of Bodies, the chronological conclusion of the series coincides with the messianic ending that is the substance of so much of Agamben’s thought on politics and philosophy. This coincidence, however, is not pure happenstance, for it testifies to the poetic orientation in Agamben’s thought to which I have already alluded; it speaks to Agamben’s desire to achieve a lyric intensity of thought, to perform (if only in an anticipatory manner) a perfect harmony between language and thought. As The End of the Poem explains, a poem’s last lines do not execute a final reconciliation. They insist instead on the perpetual strife between sound and sense. Yet through this negativity, the poem also speaks to the promise of criticism, to the way in which criticism becomes a dwelling place for the joy of poetry, and the way the joy of poetry constitutes a placeholder for the overcoming of metaphysics and sovereignty. Like the final couplet of a sonnet, The Use of Bodies reveals the truth of the Homo Sacer series by introducing a reversal, a twist on a conceit, a displacement of sound and sense, but also like a sonnet, this reversal can mean catastrophe as well as success, the stars falling down to earth as well as arrival at a new plane of existence.

Part 1: Hermeneutics of a Life

There is a risk involved whenever one associates a piece of writing with a life. From the New Critics of the mid-twentieth century on, scholars in the humanities have learned to be suspicious of equating meaning with intention, the effects of language with the will or desires of an author. There is almost inevitably an inadequacy to such procedures. The intention, the desire, or the life supposed to firmly ground interpretation turns out to be another fiction, another verse. Fabrication does not disappear. It only digs its way more insidiously into our critical practices. With this sense of artifice revealed, the practice of tying the meaning of the text to a figure standing behind the text appears for what is: a project of mastery located less in the author as such than in the critical apparatus through which one maintains canons, reinforces traditions, polices readership. Recourse to the author constitutes less an exercise in grounding than in discipline. The author comes to resemble a stern, Old Testament God, bellowing commandments, punishing readers who fail to respect the authority of a text’s origins. The late twentieth-century liberation from this authority – the so-called death of the author – is less a passage into New Testament brotherly love than a Satanic overturning of the theological ordinances of interpretation. Everything holy is profaned. The death of the author, as Roland Barthes once proclaimed, heralds the birth of the reader, the latter no longer a servant to the Word but an active participant in the weaving of the text.[ii]

Given this situation, the rise of Giorgio Agamben as a touchstone in the humanities might strike one as strange and untimely. Agamben revels in the nexus joining art and life. Biography is at the heart of much of his work, as if the truth of the self and the truth of a text could only be revealed in a reciprocal fashion. Moreover, Agamben reintroduces a hermeneutics in which origins continue to hold sway, even after millennia have elapsed. Ancient Greek and Roman philosophical and legal concepts are not relics gathering dust but the robes that clothe contemporary governance. There is something almost willfully old-fashioned about Agamben’s philosophical method, a refusal of the status quo regarding critique, as if instead of joining the rest of the scholars in the humanities in carnal-textual revelries, Agamben had snuck back into church to hear one final mass. Agamben, however, is still a contemporary, less an atavistic remainder than a sign of the times. His success, indeed, the very possibility of his method, depends on a fault-line running through the contemporary apparatus of the humanities. The so-called death of the author may have liberated readers, enabling a new interpretive polyphony, but it did so only by digging the shallowest of graves for the figure of the author.[iii] To be precise, the semiotic turn of the twentieth century (the emergence of textuality as a limitless network of signification, the marginalization of the author, the insistence on the materiality of the signifier, the privileging of language as ultimate horizon of thought, etc.) did not so much resolve as displace the problems of an earlier moment of existentialism and phenomenology. Meaning – understood as an ontological question, as a wager on Being in the face of nothingness, or as a formal concern with intentionality – only seems to get swallowed up by the turn to language, its remnants finding voice in theories of abjection, in critical refrains such as “constitutive outside,” and in recent appeals to affect, the body, and life itself. Agamben thus names the return of the repressed, as theory with a capital “T” confesses not so much to its insufficiencies as to the fact that there was always more to it than it wished to admit, something lurking, a hidden thrill or an unpleasant growth.[ii] If so many scholars have turned to Agamben, if the philosophical, political, and aesthetic vocabulary associated with his name has proved so generative, it is because he has dwelled in a threshold – the outer margins of theory – that is simultaneously contemporary thought’s ancient foundation and the rising crest of its future.

It would be unfair to reduce Agamben to a mere symptom of the shifting historical grounds of theory. There is something singular not only in the content of his thought but also in its style. The Use of Bodies demonstrates this singularity in a remarkable manner. Serving as the culmination of a nearly two-decade long project in rethinking ontology and politics, this text exemplifies Agamben’s habit of piling layers upon layers of repetitive, which is not to say redundant, interrogations of the foundational terms of Western thought, while at the same time engaging in elliptical digressions that upend, or at least sidestep, the parameters of contemporary critical apparatuses. The overall structure of the book consists of three sections, a first section on “the use of bodies,” which examines use as a mode of praxis that is entirely immanent, that knows no separation between actuality and potentiality, that is nothing other than life itself, but which also comes to be captured by the theological-ontological-political machinery of the West in its long course from ancient Greece to our own ruinous present; a second section, an “archaeology of ontology,” which performs a reduction of the history of ontology to the interlacing of language and being, or the sayable and the unsayable, and which outlines a modal ontology that would resolve, or at least render positive, the ongoing tension between essence and existence; and a third part, proposing “form-of-life” as the conceptual cipher through which a new ontology and a new politics becomes sayable, a coming political ontology that disposes not only of representation but also of identification, a politics that would coincide with an ethics of life. The narrative arc of the text, inasmuch as a philosophical tome can be said to possess one, introduces a protagonist in the form of use, as figure for an absolutely immanent life. It then follows the trials and tribulations of use as it comes to be captured by the metaphysical apparatus of the West, ensnared by the cunning of reason/sovereignty. Finally, the story concludes not so much with a triumphant breaking of bonds (the Revolution) as with the illumination of a horizon: a free use, a life liberated from the apparatus, a purely anarchic potential. What this bare-bones account of plot does not capture, however, are the true pleasures of reading Agamben, namely, the extraordinary proliferation of minor characters – the asides that are so many roads not taken in the history of Western thought, so many pockets of oddballs, misfits, and rebels.

Agamben’s attraction to these secret moments in the history of thought can be witnessed in the opening of The Use of Bodies, which calls attention not only to the work of Guy Debord but also to his life as it furtively appears on screen and in print. “It is curious,” Agamben writes in the Prologue, “how in Guy Debord a lucid awareness of the insufficiency of private life was accompanied by a more or less conscious conviction that there was, in his own existence or in that of his friends, something unique and exemplary, which demanded to be recorded and communicated” (xv). This paradoxical concord between insufficiency and exemplarity, between the trivial and the extraordinary, elaborates itself as an effect of “a constant attitude in our culture,” namely, that division of life into zoe and bios, bare life and politically qualified life. The propriety of the political, its parsing out of life into irreducible yet inextricable spheres, cannot help but secrete a certain potentiality in the most quotidian details of being. In the first volume of the Homo Sacer series (Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life), Agamben articulates the paradoxes of an apparatus of capture (the state of exception) that includes only insofar as it also excludes, that founds the law only insofar as it introduces a constitutive exception to it. In The Use of Bodies, Agamben indicates that which does not necessarily overturn the state of exception but rather recedes from it, even as it testifies to it. We have “something like a central contradiction, which the Situationists never succeeded in working out, and at the same time something precious that demands to be taken up again and developed – perhaps the obscure, unavowed awareness that the genuinely political element consists precisely in this incommunicable, almost ridiculous clandestiny of private life” (xv). In contrast to a logic of transgression, according to which the hope of another politics would be located in the improper, it is the obscure and the trivial, the shadow and the recess – the inversion of the spectacle – that offers something like hope, if perhaps also a certain danger. Agamben refers to this “homonymous, promiscuous, shadowy presence” as “the stowaway of the political, the other face of the arcanum imperii, on which every biography and every revolution makes shipwreck.” This not-quite-mixed metaphor in which the stowaway becomes a creature that can cause a shipwreck – as if the Titanic had destroyed itself not against a glacier but through an impossible collision with its own metal innards – is telling: the writing of life (biography) and the realization of politics (revolution) founder on that which in politics exceeds politics, its disavowed surplus, its trivial remnants – not the exception, which shores up the force of the law through extra-/para-juridical means, but the most unremarkable details of life in which form and substance coincide in an infinite retreat from public recognition. The life of “Guy” (as Agamben refers to him), the life shared by Debord’s friends (“Asger Jorn, Maurice Wyckaert, Ivan Chtcheglov”) and the life of Debord’s longtime romantic partner (“Alice”: Alice Becker-Ho), confound oppositions between the public and private, the social and the singular, exemplifying the condition of a present defined by the separation of life from itself (alienation) and at the same time indicating a “clandestine life” that promises a new politics only on the basis of shipwrecking this one. “Here life is truly like the stolen fox,” writes Agamben, “that the boy hid under his clothes and that he cannot confess to even though it is savagely tearing his flesh” (xxi).

“Guy Debord”: a proper name, a signature style of praxis, a singular twisting of the knot that is life itself. The proper name gives form to a singular manner in which essence and existence, zoe and bios, substance and form, come together and pull apart. Agamben’s thought on singularity echoes Gilles Deleuze’s articulation of immanence in the essay “Immanence: A Life…”[v] Immanence translates to impersonal singularity: a potential, a virtual event, a line of flight. In other words, immanence does not belong to the subject or to the person but to that which exceeds and traverses the individual without being reducible to generic attributes. As Deleuze puts it, there emerges “a ‘Homo Tantum’ with whom everyone empathizes and who attains a sort of beatitude. It is a haecceity no longer of individuation but of singularization: a life of pure immanence, neutral, beyond good and evil, for it was only the subject that incarnated it in the midst of things that made it good or bad. The life of such individuality fades away in favor of the singular life immanent to a man who no longer has a name, though it can be mistaken for no other” (28-29). The proper name, in this context, does not identify a subject; it releases forces that traverse and exceed the subject’s limits. The indefinite article in a life signals an eddy in the river of being, an instance in which being turns on itself and, in doing so, allows something new to come into existence. In his films and treatises, Debord does not simply criticize the apparatus of the spectacle, he invents an invisibility, a fugitive mode of being (a dérive, to use the Situationist term), through which another life becomes possible.

In “The Author as Gesture,” Agamben articulates this sense of immanence as surplus potentiality in terms of a distinction between the author as function and the author as gesture.[vi] Agamben reads Foucault’s well-known essay “What is an Author?” against the grain of its conventional interpretation as yet another death sentence for the author, arguing that while Foucault’s essay criticizes the author function (in Agamben’s words, “a process of subjectivization through which an individual is identified and constituted as the author of a certain corpus of texts” [64]), it nevertheless recuperates the author as something that exceeds the subject, namely, as gesture: “what remains unexpressed in each expressive act.” The author, Agamben continues, “marks a point at which a life is offered up and played out in the work. Offered up and played out, not expressed or fulfilled. For this reason, the author can only remain unsatisfied and unsaid in the work. He is the illegible someone who makes reading possible, the legendary emptiness from which writing and discourse issue” (69-70). As gesture, the author is a silence or gap in the text, the unsaid that serves as condition of possibility for the saying, the “illegible someone who makes reading possible,” an invisible force that guides thought without dictating it. In another essay, Agamben describes gesture as “the exhibition of a mediality: it is the process of making a means visible as such. It allows the emergence of the being-in-a-medium of human beings and thus it opens the ethical dimension for them” (“Notes on Gesture,” 58). The author as gesture, then, unfolds as a medium in which reading/thinking can give birth to new ways of living in the world. From this point of view, the inescapability of the proper name in criticism need not be understood in terms of an irredeemable debt to the author, as if proper names necessarily entail the circumscription of interpretation by an originary or authentic identity. Rather than reinscribing mastery, proper names indicate the means by which life breaks free from apparatuses of subjectification; they offer up a surplus of potentiality, a gestural excess, through which we might conduct our lives otherwise. “Guy Debord” not only serves as a cipher for the society of the spectacle, he also hides within his thought the inversion of the spectacle – the most trivial, the most profound, exodus from alienation. Agamben thus elaborates a hermeneutics whose concern is the secret meaning of a life, the singular events that exceed the limits of subjects, that promise the coming of another world out of the gestures in this one.

The promise of the gesture depends on the discrepancy between subjectivity and singularity, or between identification by apparatuses of power and the “incommunicable, almost ridiculous clandestiny of private life.” This recuperation of singularity from subjection entails a revision of the concept of singularity, specifically its privatization. In “Immanence: A Life…” (to draw on one of Agamben’s own touchstones), Deleuze reads the emission of a singularity in Charles Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend as the production of social commonality, as an event in which the expiration of a subject coincides with the release of a life shared in common. This interpretive procedure is the logical consequence of Deleuze’s life-long conceptualization of singularity as a means of overturning the dialectic between difference and identity, individuality and community, reality and possibility. As he puts it in Difference and Repetition: “The reality of the virtual consists of the differential elements and relations along with the singular points which correspond to them. The reality of the virtual is structure” (209). Structure, in this context, implies the co-constitution of elements and their relations. Singularities constitute turning points in the realm of the virtual, dense knots of potentiality where lines of thought and practice converge and diverge like footpaths in a dense forest. Singularities can be described as meta-relations insofar as they exceed actual relations yet are immanent to them as their condition of possibility. Paolo Virno specifies the relationality of singularity by distinguishing it from identity. Whereas identity is “reflexive (A is A) and solipsistic (A is unrelated to B): every being is and remains itself, without entertaining any relations whatsoever with any other being,” singularity “emerges from the preliminary sharing of a preindividual reality: X and Y are individuated individuals only because they display what they have in common differently” (61). It would be a mistake to treat Virno and Deleuze’s ways of thinking as if they were the same, but they do share a common sense of singularity as a difference through and of relation.

In contrast, for Agamben, singularity retreats from relationality. His hermeneutic becomes hermetic not only because it seeks to recover secret meaning but also because it valorizes secrecy as such. The shadowy, the fugitive, and the incommunicable serve as placeholders for a politics to come insofar as they involve a subtraction from the order of things. This subtraction, which goes under the name of singularity, doubles as a suspension of the social, a severing of the constitutive relationality of political subjectivity that Agamben typically understands in terms of bare life, the state of exception, and sovereign power. The “stowaway of the political,” as Agamben designates the clandestine potentiality of Debord’s life, can only constitute a surplus potentiality or a gestural excess by suspending the process through which beings constitute themselves through their relations with others. Agamben’s thought gravitates towards an absolute individualism, a secret individuality that exceeds the subject, an intimacy of exile. Singularity thus finds its proper figuration in the saint, in the martyr who escapes from a fallen world by going into the wilderness, who no longer respects conventional moral or legal codes but rather incarnates a divine justice irreducible to the order of things.

Part 2: The Politics of Use

The movement of thought in The Use of Bodies is double. It oscillates between mapping the apparatuses through which subjects become legible, through which they come to be identified and captured by relations of power, and tracking the fugitive emergence of a singular life, the processes whereby life escapes from the prisons (including the identifications) that hold it. Put differently, Agamben’s thought is double in the sense that it involves a constitutive tension between a politics of the im/proper, on the one hand, and a fugitive non-politics, on the other. Matters are more complicated, in fact, for the terms of this opposition themselves split apart. On the one hand, the politics of the im/proper doubles itself in the figures of bare life (life that can be killed without being murdered) and the sovereign (life that can kill without murdering, without being subject to the letter of the law). Agamben spells out the dynamics of this sacrificial doublet in previous volumes of the Homo Sacer series, articulating an anatomy of sovereign power in which power hangs on the capacity to produce, manage, and kill off life that is deemed without value.[vii] On the other hand, the fugitive non-politics doubles itself as use and form-of-life. This second doublet – the affirmative or emancipatory pole of Agamben’s biopolitical inquiry – has been explored in previous volumes of the Homo Sacer series but, for the most part, only in a cursory or preparatory fashion.[viii]

In The Use of Bodies, Agamben focuses on this second philosophical doublet, allowing the politics of the im/proper not so much to fade into the background as to stand out as a leech on pure immanence, a parasite draining a fugitive vitality. This becomes strikingly clear in Agamben’s articulation of use (chresis) through the figure of the slave. In Aristotle, “the use of the body” (he tou somatos chresis) involves command (the master commands the slave), but the service mobilized by this command is not productive activity, for it is not defined by a product but rather by the operation itself, by a means without an end. In use, activity coincides with life. This coincidence implies a series of indistinctions, between one’s own body and the body of another (the slave is the animate instrument of his master), between physis and nomos (the living body becomes indistinguishable from the rule or the procedures dictating its actions), between doing and living (one becomes one’s activity). The slave, then, cannot be identified with the worker, for not only does the slave lack a wage, she also performs an activity lacking the determinations of labor. This indetermination renders the slave the condition of possibility for the human and for the subject of politics proper (the two being the same in Aristotle): “The slave in fact represents a not properly human life that renders possible for others the bios politikos, that is to say, the truly human life. And if the human being is defined for the Greeks through a dialectic between physis and nomos, zoè and bios, then the slave, like bare life, stands at the threshold that separates and joins them” (20). If production/artisanship (poiesis) and political activity (praxis) sketch the contours of the human in Aristotle, use is the background against which the human becomes visible; it is the invisible current of life-activity through which, against which, subjects identify themselves as human subjects irreducible to animal life. Agamben indicates the modern relevance of this paradigm, when he draws a connection between the ancient slave and modern technology. The “symmetry between the slave and the machine” arises not only from them both constituting figures of the “animate instrument” but also in the ways that they both govern anthropogenesis (the becoming human of the human). Modern technology, which in Agamben’s capacious framework includes the apparatus of the factory, the corporate workplace, and the laptop of the free-lancer, maintains the process of outsourcing the human, of constituting the human only by way of an inhuman exception. Use, then, in the first instance, implies a critical theory of instrumentality whose distinguishing feature is the zone of indistinction that it opens up between passivity and activity, a zone that constitutes the disavowed substrate of Western political economy.[ix]

In the conceptual maneuver that is his signature, Agamben discovers in use the potential of life. That which is most abject becomes the condition of a politics to come. This maneuver is not so much a reversal as an immanent disruption of the very logic partitioning the positive and the negative. Use is a third term that simultaneously enables the constitution of the human as a domain of propriety and enables the undoing of this domain. Examining texts by Plato, Paul, Heidegger, Foucault, and Deleuze (among others), Agamben’s archaeology reveals use as an activity that “renders inoperative” the dichotomies between subject and object, active and passive, master and slave. In the manner of middle-voice verbs – verbs that are neither transitive nor intransitive, or that are both at once – use describes an activity in which one affects oneself, becomes oneself by working on oneself. In reference to Spinoza, whose theory of immanent causality is a touchstone in The Use of Bodies, Agamben articulates use as follows: “Here the sphere of the action of the self on the self corresponds to the ontology of immanence, to the movement of the autoconstitution and of autopresentation of being, in which not only is it not possible to distinguish between agent and patient but also subject and object, constituent and constituted are indeterminated” (29). Agamben articulates the stakes of this “relationship of absolute and reciprocal immanence” in discussions of sadomasochism and poetry, among other practices. Sadomasochism enacts a parody of mastery, a theatrical putting into play of relations of servitude in which sadist and masochist “are not two incommunicable substances, but in being taken up into the reciprocal use of their bodies, they pass into one another and are incessantly indeterminated. […] That is to say, sadomasochism exhibits the truth of use, which does not know subject and object, agent patient. And in being taken up in this indetermination, pleasure is also made non-despotic and common” (35). If use suggests a path towards freedom, if it recuperates an existentialist demand for freedom understood as the concrete meaning of a life intensely engaged with the world, it does so not by tracing a line that moves from passivity (bondage) to activity (emancipation) but rather by displacing that opposition in favor of a virtuous circle: freedom as coming alive to oneself; freedom as the endless reversal of social position; freedom as ontological force capable of founding and subverting the subject.

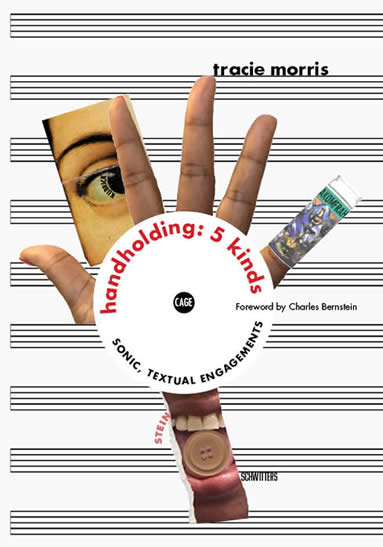

Poetry appears in Agamben’s discussion of use as a constitutive tension between mannerism and style. In a chapter entitled “The Inappropriable,” Agamben conceptualizes poetry as a “gesture” that masters a language, makes a language proper, and at the same time renders a language foreign, defamiliarizes it. In the gesture of poetry, style names a “disappropriating appropriation” (the making strange of a language in which one is at home) and manner “an appropriating disappropriation” (the making proper of a language that is inherently common, which is to say improper). Although poetry names the constitutive bond between style and manner, Agamben privileges the former over the latter, for style, in its making the familiar strange, indicates the possibility of that which exceeds the opposition between the proper and improper, namely, the inappropriable. The inappropriable does not negate property but renders it inoperative, which is to say that the inappropriable suspends the terms of property by stepping beyond modes of production (the relations of production and forces of production, to use the Marxist terms). This stepping beyond implies an entry into the common, into an intimacy that defies the dimension of the personal. Neither public nor private, “[w]hat is common is never a property but only the inappropriable” (93). Agamben participates in the contemporary discussion of the commons, or the political conversation regarding social relations that not only do away with private property but that also re-organize production beyond the oppositions between private and public, individual and collective, liberal and socialist.[x] However, for Agamben, the inappropriable common does not imply the emergence of a new mode of production, as it does, for instance, in the work of Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri. Instead, it implies the suspension of productivity as such, the advent of activity without production, of being without operativity. The measure of use becomes its immeasurable negativity, its defiance not only of proper conduct or social norms but of the facticity of conditions as such.

Agamben thus privileges a doing whose power is negative without being dialectical. Use is not the transformation of latent forces of production into new relations of production, nor is it a more general capacity for giving birth to a new world in the burnt out husk of this world. Instead, use is a kind of poetry, and poetry is the dwelling place of the inappropriable – an exile from agency, from appropriation, that is also an ontological freedom: freedom not to appropriate oneself but to experience the release of the impersonal singularities of potential that traverse one’s existence. Poetry, as I have already claimed, is not a mere genre for Agamben. Instead, it names a reunion of being and thought, of soul and cosmos, of practice and intellect. In turning to poetry in his discussion of use, Agamben performs a reflexive apprehension of his method in terms of its horizon. He acknowledges that what is at stake in his politics to come is not a transformation of social conditions but a revision of ontology through style (the making strange of the customary, the rendering inappropriable of that which is most proper). Not freedom as substance but freedom as mode. If use names the path to freedom, then the experience of use, its mode of expression, is poetry. Praxis becomes poetry when it becomes a means without an end, a communicativity without information, a doing liberated from determination: inoperativity.

Agamben’s conceptualization of freedom as inoperativity explicitly suspends a dialectical thinking of freedom. It refuses not only the teleological impulse frequently (if perhaps wrongly) associated with dialectical thought. It also refuses the philosophical procedure of the Aufhebung according to which negation implies both overcoming and preservation, or transformation as a decisive change that operates by drawing out that which in a being exceeds its being thus. I tend to agree with Fredric Jameson in understanding many of the canonical repudiations of the dialectic (for instance, those by Deleuze, Derrida, and Foucault) as polemical reductions of Hegel and Marx whose purpose is to invent new theoretical strategies – strategies that may themselves turn out to possess their own dialectical rhythms.[xi] That being said, for the sake of this argument, I want to examine what Agamben’s wager against the determinate negations of the dialectic allows him to think. The radical quality of Agamben’s eschewal of the dialectic comes from its insistence on potentiality as an indeterminate “abyss”:

Other living beings are capable only of their specific potentiality; they can only do this or that. But human beings are the animals who are capable of their own impotentiality. The greatness of human potentiality is measured by the abyss of human impotentiality.

Here it is possible to see how the root of freedom is to be found in the abyss of potentiality. To be free is not simply to have the power to do this or that thing. To be free is, in the sense we have seen, to be capable of one’s own impotentiality, to be in relation to one’s own privation. (“On Potentiality,” 82, emphasis in the original)

Agamben identifies freedom with negation, but this negation is not determinate negation. It is privation: the suspension of the capacity to do this or that in favor of the capacity to not do. To articulate freedom as an “abyss” is to suggest that it involves an at least potential retreat from worldly objects, duties, projects, and intentions; it is to suggest that an act is free only insofar as it could not have been done. Freedom thus defines itself in terms of a capacity for refusal in the most general sense; Bartleby’s “I would prefer not to” (that polite, intentionless negation eschewing the division between active and passive) becomes the measure of emancipation.[xii]

Agamben’s formulation of impotentiality as the measure of freedom is a peculiar one. Its insistence on indetermination (neither this nor that) implies a pure voluntarism, albeit a voluntarism stripped of an attachment to volition or will power. There is a kind of willfulness without will, an intentionality without subjectivity, that operates as a crucial premise in much of Agamben’s thinking. It is as if the impersonal singularities that we examined in the previous section were arrows launched towards a target without anyone having pulled the drawstring of the bow. This voluntarism, I would suggest, is at work in Agamben’s proposition of use as a kind of primordial version of doing in excess of a secondary or contingent division between passivity and activity, bondage and agency. It is difficult not to recall the crucial dialectical insight in Marx’s theorization of use, namely, that insofar as use becomes use-value, insofar as use enters into a dialectical relationship with exchange-value or becomes subsumed by the capitalist value-form, use is determined by specifically capitalist conditions, including not only the specific locale of the workplace but also the entire realm of capitalist social reproduction.[xiii] My point is not to lament Agamben’s insufficiency in respect to Marxist critique but to pose the question of whether or not a thinking of freedom without social and historical determination can amount to anything more than the valorization of unworldliness as such. What can it mean to think freedom as predicated on a potentiality for complete indetermination in determinate contexts?

The implications of this question become even more pressing when we consider that Agamben elaborates the concept of use through an analysis of slavery. Although he focuses his attention on ancient practices of enslavement, Agamben’s theorizing cannot escape the pull of the modern institution of transatlantic slavery, not least because the object of the Homo Sacer series is the persistence of archaic political formations in modernity. Agamben’s meta-narrative of politics, his account of politics in terms of a “hidden matrix” or “nomos,” immunizes his theorization of freedom from taking into account the vicissitudes of bondage and emancipation entailed not only by modern slave trade but also by colonialism.[xiv] This immunization results in a certain poverty at the heart of Agamben’s philosophy, a void that comes from a failure to reckon with historically-determined social complexities. While I do not have the time to elaborate the point, modern slavery complicates Agamben’s concept of freedom, because the slave revolt and marronage are acts of liberation that would seem to reverse Agamben’s account of freedom predicated on impotentiality: in these cases, freedom does not realize itself in/as an “abyss,” rather freedom surges up from an abyss – from what Orlando Patterson calls “social death”[xv] – as an overturning of the political assemblages that define personhood in exclusionary terms. Alexander Weheliye’s Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human offers a brilliant upending of Agamben’s theorization of freedom. On the one hand, Weheliye supplements the figure of bare life, showing how, at least in the context of modernity, biopolitics is inextricable from racialization, which is to say that theories of bondage and emancipation cannot avoid the specific histories of racialized political violence. On the other hand, Habeas Viscus defines freedom not as impotentiality but as a surplus of potentiality, a determinate multiplicity of potential genres of humanity irreducible to the figure of Man (the white supremacist, heteronormative, and phallogocentric institutionalization of the human): “As an assemblage of humanity, habeas viscus animates the elsewheres of Man and emancipates the true potentiality that rests in those subjects who live behind the veil of the permanent state of exception” (137).[xvi] If freedom is irreducible to a set of positive determinations, it nonetheless exceeds the negativity of an unworldly abyss – or, to paraphrase Marx, humans make their own history, but not in conditions of their own choosing.

Part 3: Immanence as Imperative, Life as Horizon

We have gathered up those strands of Agamben’s affirmative biopolitics – his project to liberate life – that pertain to praxis. Use is that genre of practice in which living and doing coincide, and this inseparability renders inoperative the apparatus dividing life from itself. Use opens onto the inappropriable; it does not so much abolish a regime of property as allow a fugitive intimacy to bloom. In locating this project of liberation within the domain of the apparatus, that is, inside of dominant power formations, Agamben commits himself to a methodological imperative towards immanence: the adequacy of thought finds its measure not in the degree to which one transcends the world but rather in the degree to which one dwells in the potentiality of this world. In The Coming Community, Agamben proffers a name for this absolute immanence: “the Irreparable.” The irreparable is “that things are just as they are, in this or that mode, consigned without remedy to their way of being. […] How you are, how the world is – this is the Irreperable” (90). This “without remedy” does not imply resignation, for the “how” of things always includes the potentiality not to be this way. The irreparable signs itself doubly as both “necessarily contingent” and “contingently necessary.” The world is not otherwise, its essence coincides with the mode of its existence, but this mode of existence – being’s thusness – includes the seeds of a fulfillment in which things would remain as they are, yet utterly transformed. The irreparable designates the paradoxical point at which an atheistic refusal of salvation becomes indistinguishable from redemption. Things are what they are, and what they are is hope incarnate, potentiality as such – change in its purest form.

Agamben’s commitment to immanence exceeds methodology, for it also constitutes the substance of his ethics and politics. Immanence, specifically, the immanence of life to itself, becomes the horizon of Agamben’s thought, which is to say that the method not only orients itself towards the goal of liberation but also attempts to perform it, at least virtually. Absolute immanence names the point at which life and world become indistinguishable in a commonality that knows no propriety. If use names the activity, the mode of praxis, through which the inappropriable thusness of the world comes into play, then form-of-life names the incarnation of the inappropriable, the living of a commonality that knows no alienation. Agamben defines form-of-life as the rendering inoperative of the division between zoe and bios, between animal life and political life. In positive terms, form-of-life is that third term that springs up when “living and life contract into one another and fall together”:

A life that cannot be separated from its form is a life for which, in its mode of life, its very living is at stake, and, in its living, what is at stake is first of all its mode of life. What does this expression mean? It defines a life – human life – in which singular modes, acts, and processes of living are never simply facts but always and above all possibilities of life, always and above all potential. And potential, insofar as it is nothing other than the essence or nature of each being, can be suspended and contemplated but never absolutely divided from act. (207)

Life is not essence, not a truth concealed behind being. Or, life is essence, but essence is nothing other than existence lived out in the plurality of its modes. Life passes without remainder into the way of things, and the way of things is not static but potential, the spreading out of an array of possibilities. The apparatuses of sovereign power split life into zoe and bios. In doing so, they anatomize life into so many components capable of being administered, imprisoned, and sacrificed. Power transforms life into managable facts, the quanta of governance. In contrast, form-of-life is not the facts of life but rather the suspension of facticity in the name of the possibilities lurking in the thusness of the world. This potentialization of life should not be understood as a kind of self-actualization, because the welling up of potentiality dismantles, rather than reinforces, identity. In other words, we are not dealing, here, with a self-help discourse involving a therapeutic recovery of the authentic self.[xvii] Drawing on Paul’s Letters in the Biblical New Testament, Agamben articulates this project in terms of “destituent potential”: “the capacity to deactivate something and render it inoperative – a power, a function, a human operation – without simply destroying it but by liberating the potentials that have remained inactive in it in order to allow a different use of them” (273). This destituent potential, which Agamben associates with Paul’s messianism, provokes a destitution of identity (a “deposition without abdication”) in which the self is not destroyed but released, not annihilated but given a new life. Selfhood no longer amounts to an identifiable substrate from which one’s characteristics would hang like so many ornaments. Instead, life is in the living, and this living is potential, a real surplus of possibility immanent to existence. This life of surplus circles back to the concept of use, or a praxis in excess of the constraints of statist and capitalist power relations, for the activity of form-of-life, of life that has wholly passed into its modes of existence, no longer allows for the division between propriety and impropriety. In sum, form-of-life emerges from an exercise of destituent potential, and this exercise does not produce new subjectivities but rather enacts a permanent suspension of identity through which life comes to know itself without separation, without the heteronomy of governmentality. Agamben lends a provocative, indeed, utopian, name to this state of affairs: “the Ungovernable”: a potentiality “situated beyond states of domination and power relations” (108).

In many respects, Agamben repeats Foucault’s thinking regarding the relations between subjectivity and power.[xviii] In “The Subject and Power,” for instance, Foucault distinguishes his analytics of power from an analytics of exploitation or domination, remarking that what is at stake is an apprehension of the production of subjectivity by power. A consequence of this claim is that liberation no longer implies liberation from power as such but rather liberation from specific relations of power. “Maybe the target nowadays,” Foucault writes, “is not to discover what we are but to refuse what we are” (785). He continues in this direction:

The conclusion would be that the political, ethical, social, philosophical problem of our days is not to try to liberate the individual from the state and from the state’s institutions but to liberate us both from the state and from the type of individualization which is linked to the state. We have to promote new forms of subjectivity through the refusal of this kind of individuality which has been imposed on us for several centuries. (ibid.)

In a crucial distinction, Foucault does not reject individuality as such but rather specific “type[s]” or “kind[s]” of individuation, which is to say specific genres of selfhood. Refusal, in this context, does not mean a leap into nothingness. Instead, it suggests a revision of governance: refusal as reinvention of governance. The second and third volumes of the History of Sexuality series (The Use of Pleasure and The Care of the Self), as well as Foucault’s late lectures (from The Hermeneutics of the Subject to The Courage of Truth), do not offer a programme for this project of refusal, but they do indicate the potentiality for it: the ancient practices of problematizing the self indicate, through their stark differences from modern power formations, the non-identity of the self and power as a fundamental axiom of thought and practice. Moreover, they articulate this non-identity in a productive manner, as inventive of new forms of life, new ways of being in the world with others. Here, we find a disagreement, both philosophical and political, between Foucault and Agamben: for Foucault, the “Ungovernable” (the pure anarchy that Agamben associates with the immanence of a form-of-life) can only be a passage from one form of governance to another, a process of refusal that becomes a process of political invention. Foucault’s emphasis is not on the “Ungovernable” but on the possibility of governing otherwise. In contrast, for Agamben, the Ungovernable may not be a telos, but it is certainly the horizon of his political thought, the shapeless music to which his critique of sovereignty lends its ear.

Part 4: The Rhythm of Being (Human)

Agamben’s recuperation of life hinges on his archaeology of ontology (Part II of the The Use of Bodies), which is not a neutral apprehension of the history of ontology so much as a strategic intervention into it. The ability to think a form-of-life and the concept of praxis (use) implicated in it has as a necessary premise an articulation of mode. Modality defines an alternate lineage in the history of ontology, an undercurrent of philosophical investigation in which Agamben finds the seeds of an ontology to come. In The Use of Bodies, mode is the philosophical operator that resolves the tension – co-extensive with the history of Western philosophy in Agamben’s account – between essence and existence, necessity and contingency, Being and beings. “The idea of mode,” Agamben puts it at one point, “was invented to render thinkable the relation between essence and existence” (155). If at the heart of ontology is the saying of being as being (the gathering up of the Being of beings) and if the history of ontology has alternated between putting the emphasis on one side of the “as” or the other (the sides of existence and essence, respectively), then the alternative ontological project of modality shifts the emphasis onto the adverbial “as”: neither essence nor existence are more real; neither that it is nor what it is rules thought; modal ontology shifts the accent to the as of being, to being as it exists, to being in its mediality. “We are accustomed to think in a substantival mode, while mode has a constitutively adverbial nature, it expresses not ‘what’ but ‘how’ being is” (164). Agamben offers a useful analogy in elaborating the “how” of being, namely, rhythm: “Mode expresses this ‘rhythmic’ and not ‘schematic’ nature of being: being is flux, and substance ‘modulates’ itself and beats out its rhythm – it does not fix and schematize itself – in the modes. Not the individuating of itself but the beating out of the rhythm of substance defines the ontology that we are here seeking to define” (173). Mode is the rhythm of being, which lives not below being as a substrate nor above it as a cosmos but rather is immanent to it, is no more and no less than the temporalization and spacing of being – its being put into play. Mode names the exhaustion of being in its expression, the irreparable just so of existence. Rhythm is in fact more than an analogy for Agamben, given that his articulation of ontology leans heavily on language, or the act of enunciation. Agamben emphasizes that ontology is inextricable from the saying of being, or as he puts it (riffing on Aristotle): “[B]eing is said (to en legetai…), is always already in language” (116-17). In its most radical version, this inherence of being in language means “[b]eing is that which is a presupposition to the language that manifests it, that on presupposition of which what is said is said” (119). Ontology turns on the relationship between the sayable and the unsayable, and if there is perhaps something ultimately unspeakable about being, if there is something in being which can only be touched on, never expressed outright, it is perhaps only because the act of enunciation itself makes it so retroactively: the unsayable is the underside of the sayable, the palpable silence between uttered syllables.

The division of being into essence and existence is thus a consequence of the relationship between being and language. For Agamben, then, the project of a modal ontology is also the project of saying being with a different rhythm. This rhythm would depart from the presuppositional logic according to which the Being of beings constitutes itself as the unsayable substrate (retroactively posited) of the sayable. Being would become being such as it is, or the being of being would be nothing other than its modes of expression. In expression, the “modal relation – granted that one can speak here of a relation – passes between the entity and its identity with itself, between the singularity that has the name Emma and her being-called Emma. Modal ontology has its place in the primordial fact […] that being is always already said: to on legetai… Emma is not the particular individuation of a universal human essence, but insofar as she is a mode, she is that being for whom it is a matter, in her existence, of her having a name, of her being in language” (167). In turning to a proper name, “Emma,” Agamben indicates a recursive pathway between the sections of his book, a wormhole through which his modal ontology (Part II) immediately gives way to the ethico-political dimension of form-of-life (Part III). A form-of-life can emerge only when ontology, the saying of being, becomes modal. Life remains divided from itself so long as being and saying remain at odds with one another. This intertwining of the saying of being and the living of a life entails an interpenetration of ontology with ethics: “In order to think the concept of mode, it is necessary to conceive it as a threshold of indifference between ontology and ethics. Just as in ethics character (ethos) expresses the irreducible being-thus of an individual, so also in ontology, what is in question in mode is the ‘as’ of being, the mode in which substance is its modifications. Being demands its modifications; they are its ethos: its being irreparably consigned to its modes of being, to its ‘thus’” (174). The possibility of living a life (form-of-life) and the possibility of saying being (modal ontology) are one and the same, or, more precisely, these possibilities relate in a chiasmic pattern, so that the living of a life and the saying of being are like the recto and the verso of a book – perfectly suited to one another, yet non-identical.

The scope of this mutual imbrication between ontology and ethics becomes clear, when one considers Agamben’s identification of first philosophy with anthropogenesis, or the becoming human of the human. “First philosophy is the memory and repetition of this event [anthropogenesis]: in this sense, it watches over the historical a priori of Homo Sapiens, and it is to this historical a priori that archaeological research always seeks to reach back” (111). It is not merely the possibility of an individual life that is at stake but the life of the species. Agamben does not mean this in a narrowly biological sense, though certainly biology comes into play along with the biopolitical.[xix] Instead, ontology’s watch over anthropogenesis involves the plural modes of governance through which reason – political and ethical rationalities – guides the becoming human of the human. Thus the “mechanism of the exception is constitutively connected to the event of language that coincides with anthropogenesis,” which is not to say that there is no becoming human without the sovereign exception but rather that insofar as modernity is governed by the logic of the exception, the human likewise can only exist in an exceptional manner (264). Agamben delineates this human exceptionalism in The Open: Man and Animal, showing how the operations of the anthropological machine (as he calls it) depends on a state of exception in which the animal in/of Man is at one and the same time included and excluded – excepted – from Man. In the dominant ontology of the moderns, there is no humanity without the sovereignty of the human over animal life, and this sovereignty cannot help but become a suicidal imperative, as human life seeks its purest form by introducing caesurae, or gaps, between the truly human, the not so human, and the inhuman.[xx] Of course, as is clear by now, this human exceptionalism is not the only pathway for ontology, politics, and ethics. The entire aim of The Use of Bodies (and the Homo Sacer series more broadly) is the articulation of a method that would illuminate another path for anthropogenesis, another way of becoming human – one without exception. As Agamben puts it, “This means that what we call form-of-life is a life in which the event of anthropogenesis – the becoming human of the human being – is still happening” (208). Agamben does little to spell out the content of a new humanity, and, in fact, the refusal to do so is precisely the point of his intervention. The concept of form-of-life does not offer up another humanity, for what is at stake is not the positive elements that make up this or that version of the human but rather the relationality encompassing the human. Form-of-life designates the suspension of an exceptional relation to the human; it names the human as a series of irreducibly plural modes of becoming-human. There is no substance to human life, no substrate unifying the species into a great family of Man. Human life passes into the modes through which humans live, without remainder.

This passage from ontology to anthropology is a specifically Italian philosophical gesture, at least if Roberto Esposito is correct in his assessment of Italian philosophy. In Living Thought: The Origins and Actuality of Italian Thought, Esposito argues that the contemporaneity of “Italian thought” (the Italian reads filosofia italiana, but the term includes literature, painting, and political theory, as much as it does traditional philosophy) comes from its attachment to origins in an ontological sense, its insistence on a kind of primitivism whereby the modern derives from the archaic, the foundational. This is not to claim that the modern does no more than repeat these origins, or, if that is the claim, then the repetition implies differentiation, the modern by definition involving a break from foundations. From Vico to Negri, from Machievelli to Agamben, Italian philosophy lives in the break between archaic and the modern, primitivism and futurism. In terming this maneuver an ontological primitivism, I mean to suggest not only the drawing of philosophical and political conclusions from the identification between a contemporary moment and an originary moment (on its own, that would simply be metaphysics) but also the assertion of a primal force that is productive of Being.[xxi] While Esposito’s description of Italian philosophy is surely a generalization, it is difficult not to notice in treatises such as Negri’s The Savage Anomaly: The Power of Spinoza’s Metaphysics and Politics and Virno’s When The Word Becomes Flesh: Language and Human Nature a philosophical procedure whereby ontology becomes an immediately empirical matter through anthropology, which is to say that these writings share a tendency to transform philosophical first principles (including Agamben’s assertion of the primacy of modes) into social, ethical, and political facts by way of the concept of anthropogenesis: not unlike early evolutionary biology’s attempts to trace the evolution of the species through the life cycle of an embryo, these works anticipate a retrofitting of the species through a return to originary potentiality, through a grasping of the passage from substance to mode, from genus to species. The risks of this maneuver are many, not least of all the reintroduction of an essentialism, one whose historical position subsequent to twentieth-century critiques of essentialism results in a strange synthesis of essence and its opposite: not strategic essentialism but generic essentialism, or the assertion of a commonality completely stripped of predicates, a pure potentiality identified with simply being human. What is distinctive about Agamben’s version of ontological primitivism is the way it combines a commitment to the irreparable (to being in its thusness, to the modes as such) with a politics of pure immanence (form-of-life as the lived abolition of alienation, as living contemplation of the surplus potentiality of the modes).[xxii] Political action comes to be measured by its capacity to draw on the primitive potentiality of being, to make use of that which in being is irreducible to the parasitical formation of sovereignty. Politics thus becomes a striving for beatitude: the realization of a blessedness at the heart of Being, or a perpetual renaissance of the human.

Conclusion: Lyric Intensity

Agamben’s project to re-found ontology, ethics, and politics can be described as a poetry of thought, because it not only generates a certain lyric intensity but also depends on it. To be specific, Agamben’s philosophical practice hinges on a three-fold movement: first, hierarchically paired terms are rendered inoperative; second, this rendering inoperative engenders a zone of indistinguishability in which the preceding terms become indeterminate; and, finally, this indetermination enables the emergence of a tertium, a third term that can serve as the condition of possibility for a changed state of affairs. This sequence is not chronological but logical. Rather than a diachronic unfolding through time, these three moments articulate themselves in a synchronic fashion, bursting forth as the necessary complements of one another. For instance, the term use emerges from the rendering inoperative of activity and passivity, mastery and servitude; this rendering inoperative opens up a zone of indistinguishability in which mastery and servitude ceaselessly switch places, neutralizing their hierarchical status; and, finally, this zone of indistinguishability calls forth use as the inappropriable, as that which not only confounds relations of mastery and servitude but positively articulates a form-of-life beyond propriety. This sequence can unfold in historical time. For instance, one might conceptualize slave revolts as an evental irruption of use. However, Agamben’s philosophical excavation discovers the truth of this three-fold process only in absolute immanence, which is to say only in the gathering up of conceptual differences into singularity. Singularity is thus synonymous with lyric intensity, and, if absolute immanence (the irreparable) is the measure of thought in Agamben, then this measure cannot help but be poetic, can be nothing other than a poetry of thought.

The hermeneutic orientation in Agamben, his desire to return to the fault at the origins of Western thought and practice, may distinguish itself from classical hermeneutics in that it is not a pursuit of presence as distinct from mere beings, but this orientation still has as its horizon a recovery of presence: the restoration of life itself over and against the apparatuses of its separation. Mode becomes the means by which Agamben phrases the historical differentiations of life and the apparatuses capturing it without surrendering what I have referred to as his methodological imperative of immanence. Modality enables the instant to take place without sacrificing the force of its unity. That is to say that mode is homologous to the form of poetry, which, as Agamben explains in The End of the Poem, is defined by a constitutive tension between sound and sense, between the semiotic and semantic, and between the durée and the instant. This constitutive tension does not resolve itself in poem’s conclusion but rather

the poem falls by once again marking the opposition between the semiotic and the semantic, just as sound seems forever consigned to sense and sense returned forever to sound. The double intensity animating language does not die away in a final comprehension; instead it collapses into silence, so to speak, in an endless falling. The poem thus reveals the goal of its proud strategy: to let language finally communicate itself, without remaining unsaid in what is said. (115)

In the same manner, The Use of Bodies allows being to finally communicate itself, without remaining unsaid in what is said, through the tertium that is the concept of form-of-life.[xxiii] Form-of-life is itself a lyric intensity defined by the constitutive tension between sound and sense, or, in terms more appropriate to our discussion, between bios and zoe. It is not so much the abolition of the dichotomy between political life and animal life that occurs in the emergence of a form-of-life as “an endless falling,” a collapse of each term into the other so that they express themselves otherwise. Agamben understands this otherwise as a suspension of relation. In his terms, the relatedness of zoe and bios (that is, the exception) gives way to “contact”: “Just as thought at its greatest summit does not represent but ‘touches’ the intelligible, in the same way, in the life of thought as form-of-life, bios and zoe, form and life are in contact, which is to say, they dwell in non-relation – and not in a relation that forms-of-life communicate. The ‘alone by oneself’ that defines the structure of every singular form-of-life also defines its community with the others” (Use 237). This is the other face of lyric intensity in Agamben’s immanent method, namely, absolute subtraction. Immanence comes to be measured in relation to a horizon of complete withdrawal from relation. Agamben declines this subtraction as “intimacy,” an “esoterism” that defies knowledge qua means of representing (or capturing) being. We return, here, to the matter of Agamben’s prologue to The Use of Bodies, to Guy Debord and company, as they rescue politics not by organizing the Revolution but through a fugitive intimacy in which the completely quotidian coincides with the potential for change. The break with a politics of representation or recognition (the pillars of the hegemonic politics of our time: liberal democracy), as well as the break with the state of exception (the tyrannical supplement to that same liberal democracy), thus comes to be predicated upon a break from relationality as such. There is perhaps no better figure for this break from relationality than the lyric poem, at least in Agamben’s formulation of that genre, in which sound finds its truth in silence, relation its truth in the solitude of the apostrophe. In this way, it is not merely philosophical thought which takes the shape of a poem but also that politics to come which is the fruit of the Homo Sacer series.

Agamben’s poetry of thought requires a very specific idea of both poetry and poetry’s relationship to philosophy. This idea belongs to a Romantic tradition of thinking poetry, one in which poetry names a pursuit of truth by other means, a mode of philosophical reflection in excess of the concept (the Begriff). Friedrich Schlegel’s articulation of the mutual imbrication of philosophy and poetry is perhaps closest to Agamben’s own, revolving as it does around paradox, beauty, fragments, immanence, reflection, and redemptive power. “From the romantic point of view,” Schlegel writes, “even the vagaries of poetry have their value as raw materials and preliminaries for universality, even when they’re eccentric and monstrous, provided they have some saving grace, provided they are original” (179). The medium through which poetry communicates this “saving grace” to philosophy, the aether through which poetry and philosophy achieve a state of indistinguishability, is irony, understood as “permanent parabasis”: a constant suspension of frames of reference, an infinite series of reflections on the basis of an equally infinite transgression of convention. “Philosophy is the real homeland of irony,” Schlegel writes, only to qualify the assertion by adding, “Only poetry can also reach the heights of philosophy this way […]. There are ancient and modern poems that pervaded by the divine breath of irony throughout and informed by a truly transcendental buffoonery. Internally: the mood that surveys everything and rises infinitely above all limitations, even above its own art, virtue, or genius; externally, in its execution: the mimic style of an averagely gifted Italian buffo” (148). Agamben’s inheritance of the Romantic idea of poetry elides what Paul De Man would not have us forget, namely, the buffoonery of irony, its ceaseless undoing of the narrative line (“…above all limitations…”), its undermining of its own premises, the shell game according to which every promise of presence delivers only an empty cup.[xxiv] Irony disrupts, troubles, complicates, and subverts. It does not resolve or harmonize. Agamben’s reconciliation of poetry and philosophy depends on a subsumption of irony by messianism: his conceptualization of form-of-life as a contemplative posture stemming from the suspension of the transcendental frame implies a beauty without disruption, a “saving grace” without an earthly sticking point, a harmony of poetry and thought immune from irony. It is not so much that Agamben eliminates irony but rather that he domesticates it, in much the same way that he does not leave behind earthly matters but rather saps them of their gravity, their determinateness. The solitude of Agamben’s poetry of thought is that of the grumpy hermit who is perfectly comfortable in his habits, completely at home in his secrecy, enjoying a negativity that only he can hear.

It is undoubtedly a paradox that Agamben rescues politics from its current poverty only by making recourse to solitude. The problems of how we live together, of how we organize polities, are not resolved but displaced through an insistence on form-of-life as that which escapes each and every apparatus of power. Of course, paradox is the motor of Agamben’s thought.[xxv] Agamben not only excavates the paradoxes structuring the history of Western thought and politics (for instance, the paradox of the state of exception). He also draws on the power of paradox in order to depose other paradoxes. However, this particular paradox – the paradox of a politics whose basis is not sociality but solitude, not relation but subtraction – is the crux of the Homo Sacer series, its fundament and its inescapable fault. In short, Agamben’s thought shipwrecks insofar as it conflates a critique of representation with a critique of relation. One could already anticipate this catastrophe a quarter century ago in The Coming Community, where Agamben articulates a “community without presuppositions and without subjects” in terms of the “whatever” or “whatever being.” There is something fascinating in the whatever’s diagonal traversal and refusal of the opposition between identity and difference, as well as universality and particularity, but this fascination cannot compensate for the void at its heart: lack of relation, absence of sociality. Agamben’s Homo Sacer series, in many respects, constitutes the methodical working out of the much more elliptical formulations of The Coming Community, and, as such, it remains caught up in this void, ensnared by this absence. Moreover, this fault also amounts to a misreading of the concept of power, especially as elaborated by one of Agamben’s central interlocutors, Foucault. For Foucault, power is irreducible to domination, and if Foucault (like Agamben) frequently equates the contestation of power relations with the refusal of subjectivity, this contestation does not result in the departure from power as such but rather its transformation.[xxvi] For Foucault, it is not “the Ungovernable” that is the horizon of his method but the possibility of governing otherwise. This possibility implies new genres of relation and new genres of selfhood. Agamben, we might say, confuses salvation with political transformation, making it so that the suspension of worldliness is synonymous with saving grace. In doing so, he resolves the conflicts and contradictions of our contemporary situation into an intimacy whose tone is “whatever” and whose implications are constitutively blank.

The shipwreck of Agamben’s thought results from the treatment of the political as if it were poetry. There is of course a politics of poetry, as well as a poetry of politics.[xxvii] We see this not only in the ways in which the disorder of a riot has its own rhythm, its singular dimension, but also in the myriad manners that poems mediate on political matters, suspending a certain urgency in the name of reinventing conventional understandings of what constitutes politics. However, an overlap, a chiasmic crossing, preserves non-identity, even as it institutes relation. Agamben falters insofar as he resolves this complexity into the lyric intensity of solitude. This problematic resolution pertains not only to the affirmative moment of the form-of-life but also to the diagnostic moment. As a number of critics have noted, Agamben’s overarching diagnosis of Western politics on the basis of the state of exception ignores the heterogeneity of political paradigms that haunt not only the modern period but also the periods preceding it. The state of exception may adequately figure a variety of forms of political sovereignty, but it manages to capture neither the specificities nor the general logic of, for instance, the plantation system or modern colonialism. To be clear, this is not a matter of asserting the priority of identity politics against the rarefaction of philosophy but rather of apprehending in thought and in practice the irreducibility of politics to a single figure. Agamben’s attempt to grasp the political as such reproduces the ontological division between essence and existence by equating the truth of political action with a leitmotif: the state of exception. Agamben’s quest for absolute immanence revolves around the twin poles of the state of exception and form-of-life. Although form-of-life also constitutes a tertium unsettling the bipolar apparatus of power, it can only amount to a void, a potential defined by nothingness, a whatever that evacuates sociality. A politics to come founded on the suspension of relationality resembles less redemption than it does apocalypse, the collapse in on itself of a once radiant star.

This is not to say that there is nothing worth salvaging in Agamben. If I have dwelled with such patience in the intimate contours of his philosophical style, it is because there is something compelling in it, not merely seductive but genuinely useful. I would suggest that the object of my critical desire can be summed up in a phrase: a poetics of potentiality. I write “poetics,” not “poetry,” in order to distance myself from the valorization of aesthetic experience as a source of reconciliation and redemption – the trap to which Agamben falls prey. This poetics can be understood as a means without end, or a pure mediality in which form is not pure semblance or style but constitutive of social form. Agamben institutes criticism as a poetics of potentiality in which the irreparable thusness of the world does not entail despair, for, in the world, there is a surplus of potentiality. This surplus includes negativity (impotentiality) as a necessary condition, but, pace Agamben, this negativity does not thereby define potentiality, does not constitute its object or aim. Rather, this potentiality is something like an immanent utopianism, an earthly otherworldiness. Not redemption but profanation.[xxviii] Moreover, this paradoxical transcendence in immanence is a fugitive intimacy only in the sense that it is also friendship, sociality irreducible to the status quo, an exodus no less communal for its taking leave of the dominant order of things. My proposal, then, is the following: let us socialize Agamben, let us communize his thought, let us liberate it from unworldliness and solitude by drawing on what is so powerful in it – not the esoteric but the relational, not redemption but friendship in struggle, not the saint but the comrade.[xxix]

Notes