This essay is part of a dossier on The Maghreb after Orientalism.

A Judeo-Franco-Maghrebian genealogy does not clarify everything, far from it,

but can I ever explain anything without it?

Jacques Derrida, “To Have Lived, and to Remember, as an Algerian”

To depart (so as) not to arrive from Algeria is also, incalculably, a way of not

having broken with Algeria

Hélène Cixous, “My Algeriance, in other words: to depart not to arrive

from Algeria”

Algeria is an unfinished story, no doubt for Algerians, but also for France. And for all those who cannot but continue to think through Algeria’s recent and long history of colonialism, as they think not only about Algeria and France but also about modernity, military occupation, Orientalism, Europe, armed resistance, war, and also about Zionism, Jews and Arabs, Palestine, missed opportunities, and possible outcomes. So much and more is contained in the name “Algeria”.

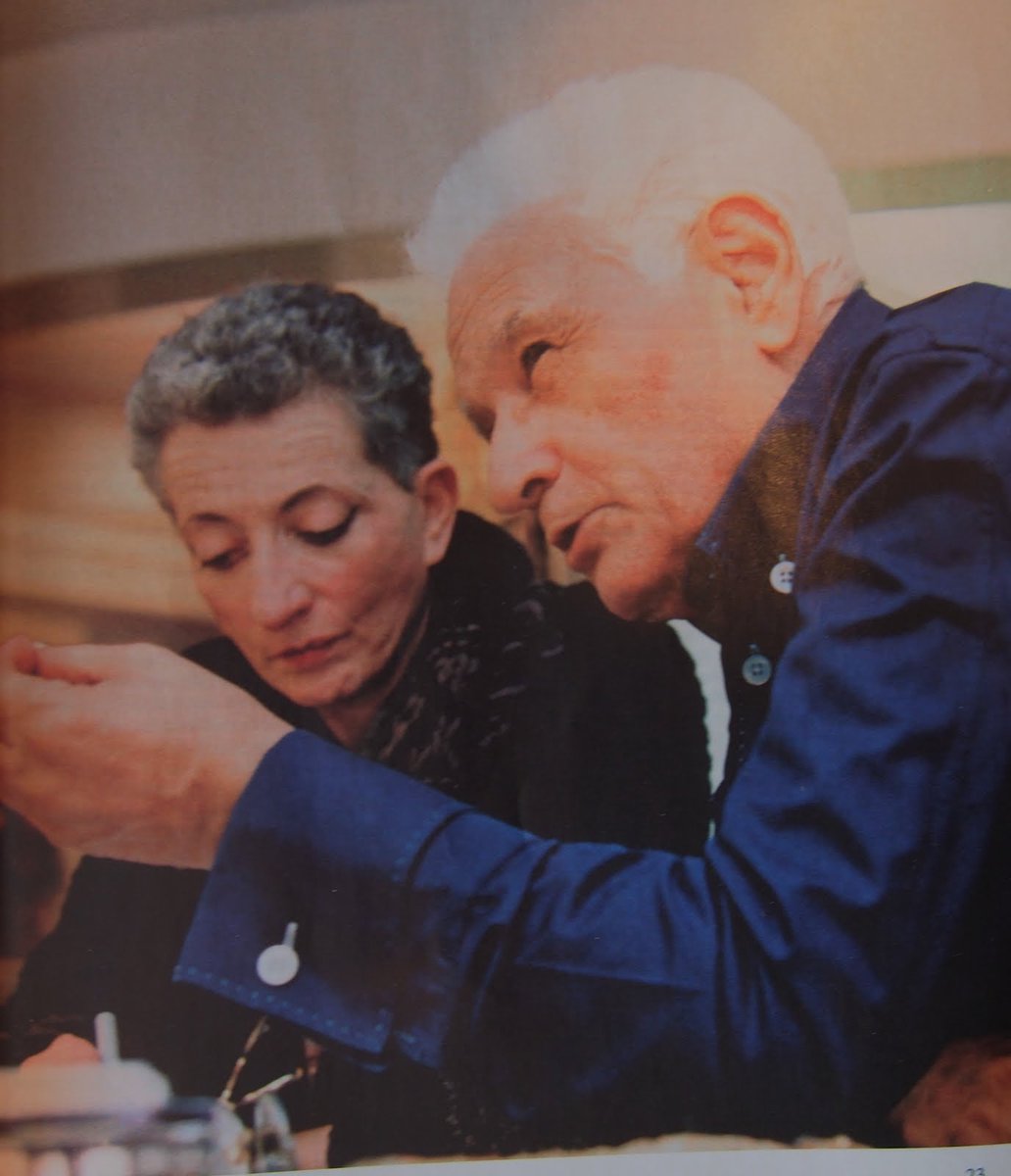

In the mid 1990s both Jacques Derrida and Hélène Cixous began to write about “Algeria” (about their “Algeria”), each investing in a writing both autobiographical and politically contemplative.[1] In their writings—primarily Le monolinguisme de l’autre ou la prothèse d’origine (The Monolingualism of the Other) (Derrida [1996] 1998)), “Mon algériance” (“My Algeriance”), “Stigmata, or Job the dog” (both printed in Cixous’s 1998 Stigmata Escaping Texts), and “Bare Feet” (Cixous 2001)—“Algeria” is a specific place: their place of birth, a nation with a particularly violent and complex history of colonial occupation, but also a name and figure of speech hosting a vast and explosive web of memories, desires, attachments, fears, projections, and identifications both personal and public.

Derrida’s Monolingualism of the Other is a short reflection on the relationship between language and mastery, identity, citizenship, and colonialism. It is also an intervention into the legacy of the relations between Arabs, Jews, and “Europe” under the conditions of French colonialism in the Maghreb, and above all a commentary about the still contested figure of the Arab Jew.[2] Derrida focuses on the particular case of Maghrebi Jews (Jews of Algeria who were granted French citizenship in 1870, lost their French citizenship under the Vichy regime in October 1940, and regained it in 1943) to talk about matters of possession and being possessed by language, memory, culture, religion, and ethnicity. But Derrida both tells and doesn’t tell the story of Algerian Jews. He both tells and doesn’t tell his story as an Algerian Jew, when he speaks of his “nostalgeria” and of his “independence from Algeria” (1998: 52) and of a “French Jewish child from Algeria” (1998: 49).

Cixous’s writings about Algeria similarly focus on her experience as a Jew, holding an outsider position in colonial Algeria, to which she belongs only through the direct touch of dust: “a sort of invisible belonging to the land to which I am bound by my atoms without nationality” (1998a: 154). Like Derrida, she centers on the drama of citizenship experienced by herself and other Jews of Algeria (“in 1940 we were thrown out as Jews” (1998a: 213). This is the pretext for her broader focus on being “at home, nowhere” (1998a: 155) and the history of colonial Algeria as a history of “brutal Algeriad . . . crudely fashioned by the demon of Coloniality” (1998a: 156).

“Algeria” is for both thinkers a way to speak the past in(to) the present, the personal in(to) the public, Algeria in(to) France, and the “Jew” (or the forbidden “J” to borrow Cixous’s expression)[3] in(to) the colonial drama as a third member along with the Arab and the French. It is also a way to speak of loss, of exile, of the limits of national belonging, the limits of origins and narratives of origins, possessing, and possession.

Both Derrida and Cixous came to “Algeria” late in their lives and writing careers. Their upbringing in colonized Algeria was for the most part absent from their texts until they began to write semi-autobiographies; until, that is, they turned their personal memories and narratives into new modes of political intervention. Indeed, as long as the two prolific writers were engaged in deconstructing Western philosophical metaphysics (Derrida) and advocating “feminine writing” (écriture féminine) (Cixous), they were unquestionably recognized as “French”: deconstruction was French; feminine writing was very French. But to continue to undo European hegemony without questioning “Europe” from its margins (and not only from “within,” by means of deconstructing key European texts) had become by the mid 1990s truly impossible. Certainly in France, which was watching the ongoing civil war in Algeria, while facing a whole series of heated legal debates about “immigration” in France itself. The critical need to question French identity and destabilize French language and citizenship is what led Derrida and Cixous “back to Algeria,” as a site (a memory, a place, a time, a past, and a future) through which to rethink the meaning of being European, and, more specifically, French.

Addressing the “traumatizing brutality of what is called the colonial war” Derrida, in a later text (“To Have Lived, and to Remember, as an Algerian”) writes: “some, including myself, experienced it from both sides, if I may say so” (Chérif 2008: 35). Writing from both sides, as it were, and from neither, is what Cixous’s and Derrida’s texts about Algeria perform textually by centering on the impossible figure of the Arab Jew. A figure that has become and then “become undone” through the not-so-subtle mechanisms of partition exercised by the French colonial administration. The “Franco-Maghrebi” is Derrida’s name for himself as the French-speaking-Maghrebi-Jew, who as such, is from Algeria but not of Algerian nationality, and who is a French citizen (at times) but who is not, cannot be, quite French. This Jew, not quite Algerian, certainly not quite Arab, can only appear in relation to French (language, citizenship, identity) given the colonial conditions dividing populations by ethnicities and policing language acquisition and national affiliations. The missing figure of the Arab Jew, the fact of its missing, the making of its impossibility, is, however, at the heart of The Monolingualism of the Other just as it is the nexus of Cixous’s Algerian texts. It is the ghostly impossible figure, whose impossibility haunts the historical narrative of colonialism told, most commonly, in terms of a binary division between two positions. In this case: colonizer and colonized, French and Arab, French and Arabic. Accounting for the impossibility of the Arab Jew in Algeria, Cixous writes: “There was not enough time. . . . There was no time. (If there had been time between Arabs and ourselves . . . the two destinal durations would have found themselves in concordance at a certain moment)” (Cixous 1998: 184).

Writing about their Algerian origins, about their early years in Algeria, about their childhood memories, and also about their becoming French (but never quite French); about their relationship to the French language, French citizenship, and writing (in French); but also about their Jewishness, about being Jewish, about being not-quite Jewish, and certainly not quite Algerian, but also not fully French. This is the similar manner in which Derrida and Cixous write about colonialism: about the colonialisms embedded in language (Derrida) but most certainly about French colonialism and its impact on them, on their own writings, on Jews, on Arabs, and on the making of the Arab Jew in Algeria. Colonialism is at the center of their texts, in the sense that is it said to be responsible for it all: responsible for everything that shaped their own personal experiences, responsible for the matrix of life in Algeria, and responsible for their writing—its content and its style. French colonialism created fractures between Arabs and Jews; it is responsible for the misery of most indigenous Algerians, and for the creation of “the Jew” as a specific figure of difference and alterity: at times more French than the Arab and other times less French, even less French than the Arab. In the context of French colonial Algeria, “Jew” is always already in relationship to Frenchness: “now we were Jews,” “now we were French” “now we were Jewfrench” (Cixous 1998b: 189).

Within this profound exposition of the nature of French colonialism in the Maghreb, Derrida and Cixous focus on the very unhappy triangle: the French, the Arab, and the Jew (“an utterly unworkable junction” (Cixous 1998b: 183). I have written elsewhere about the mobilization of animosity between Jews and Arabs/Muslims in Europe in the service of “Europe” as (Christian) secular protector (Hochberg 2006). Here it is sufficient to say that the manufactured rivalry between Jews and Arabs created under French colonial conditions is not a side narrative or a minor outcome but a profound and central aspect of the colonial structure as such. A structure very much still in operation, as a recent text by Houria Bouteldja, Whites, Jews, and Us (2016) reminds us. Regarding the ambiguous position of the Jew in France today, Bouteldja cleverly observes that the Jews are “on the one hand, dhimmis of the Republic to satisfy the internal needs of the nation state, and on the other, Senegalese riflemen to satisfy the needs of Western imperialism” (55-56, original italics). As observed by Ben Ratskoff, “the phrase ‘dhimmis of the Republic’ paints France with its own Orientalist brush—as pre-modern, religious, oppressive—and suggests that, despite their so-called emancipation, the functional role of Jews in Europe has not changed. At the same time, Jews are made into ‘Senegalese riflemen,’ the colonized colonizers to whom the perpetuation of imperial violence is outsourced” (2018).[4]

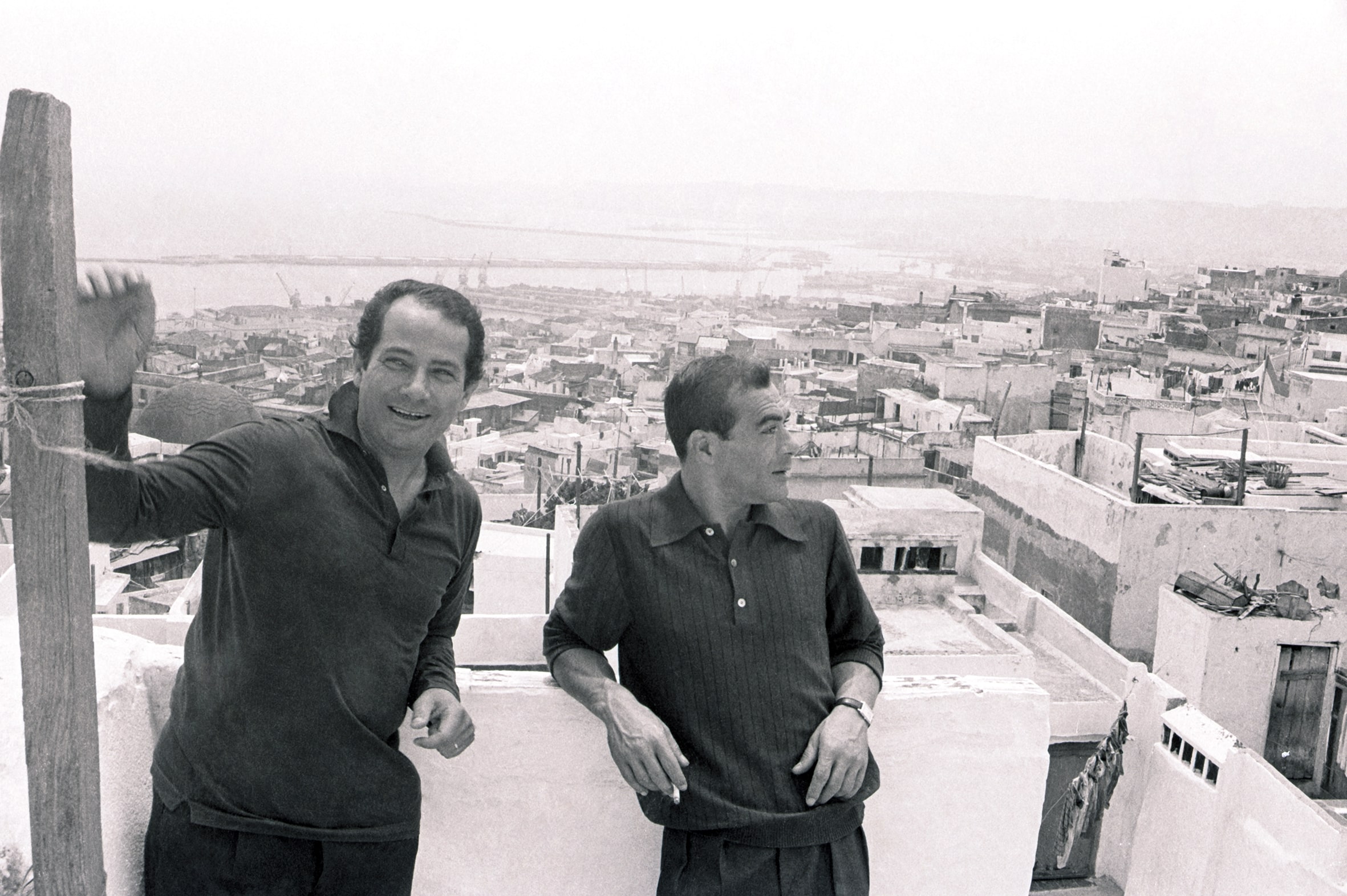

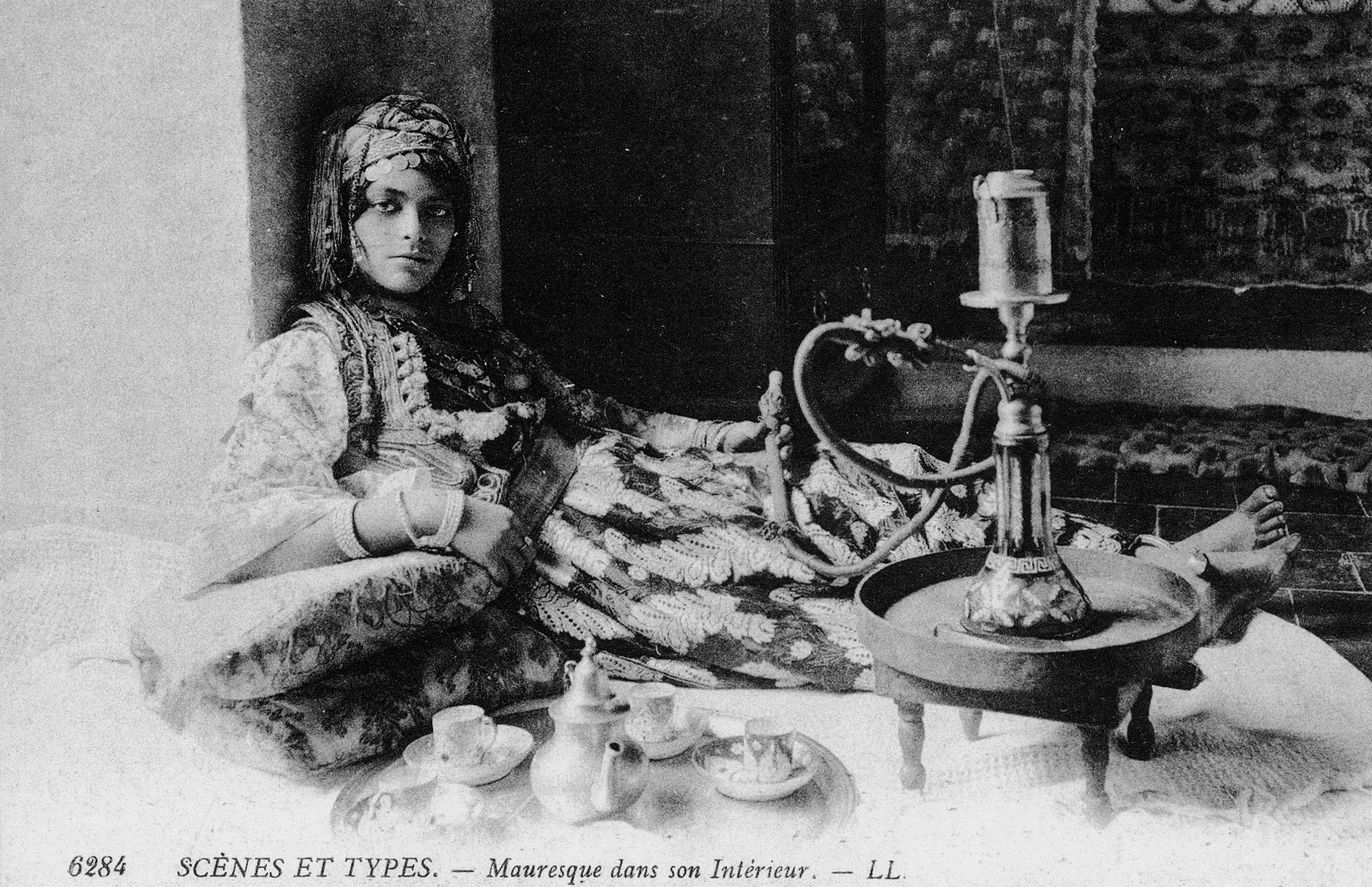

Derrida and Cixous’s texts invite us to see how colonialism and, more specifically, Orientalism create the “Jew” (as a double agent, both dhimmi and Senegalese rifleman) and at the same time create the impossibility of the “Arab Jew.” In a recent essay (delivered as a lecture), Ella Shohat shows that this process involves the ongoing production of the Jew as “less Arab” and “more French.” She calls this process “the de-orientalization of Jews” and locates it, like Derrida and Cixous, in the midst of the French colonial drama in Algeria (Shohat 2016).[5] In Orientalism, Edward Said already argued that Orientalism was responsible first for bonding Jews and Muslims together under the rubric of “Semites”—subjects of Orientalist study readily understandable in view of their primitive origins—and later for setting these two figures apart as different kinds of Orientals, managed differently by colonial forces (1979: 234). If Orientalism sometimes brings Jews and Muslims or Jews and Arabs together and sometimes sets them apart, Derrida and Cixous’s texts invite us to follow the production of what, in her analysis of French nineteenth century painting, Shohat calls “the split Arab/Jew figure” in becoming. (See Fig. 1-3) Examining French Orientalist representations of Jews from North Africa and the Middle East, Shohat demonstrates how these images tend to be familiar Orientalist images, with no distinction made between Jews and Arabs. “When and how,” she asks, do we begin to see the “Arab Jew” as a distinct figure of Orientalist imagination and colonial control? Her answer, based on a survey of Orientalist paintings, is that this happens only in the early twentieth century, “when Jews in Algeria suddenly appear to have a lighter skin tone than Muslims, and Jewish women appear without head covers.” Around the 1930s, she notes, Jews begin to be visualized as modernized, and Jewish women begin to look more French. “The split of the Jew and the Arab/Muslim is a product of the colonial area,” she concludes. “It is a cut that has not even begun to heal.” <Figures 1-3 about here>

Cixous and Derrida write about this cut. They write from the place of this cut. They write from this cut and as its outcome. They write as Jews-already-not-Arabs, already (almost) French. They try to recapture the becoming of this writing position without, however, naturalizing any pre-given identity positions (i.e., “Jew,” “Arab,” “French,” “native”). Writing about identities in becoming, about Jews becoming less Arab and more French, both writers attempt to write from a different position: not “as a Jew” or “as an Algerian” or “as a French person.” Their writing seeks to undo these identities while recognizing they cannot be undone: “Certain Jews truly wanted to love France. But it was a love by force. We wanted to love Algeria. But it was too early or too late” (Cixous 1998a: 163).

The focus on the Jew, which is obviously an autobiographic detail, is not just that. It is also an opportunity to speak a different language: to speak from within the colonial cut and within the Orientalist operation as both an outcome and a resistant trace. To speak not the language of historicity, not the language of the law, not even the language of literature, but a language of a cut as prefigured through the figure of the always already impossible Arab Jew. Stigmata, “the fertile wound” (Cixous 1998b: 182).

The term Orientalism is not a term either Derrida or Cixous use. Said’s work Orientalism is similarly missing from Derrida and Cixous’s autobiographical texts. And this is perhaps not surprising. Said’s style and framework of analysis are utterly foreign to their writings. Orientalism doesn’t leave a lot of room for thinking in the spaces between binaries and that is precisely what both Cixous and Derrida do, albeit differently. If anything, one could say that both Cixous and Derrida, at times, mobilize an overtly Orientalist language to talk about France, Algeria, Arabs, and Jews (see, for instance, Cixous’s “unshakable certainty that ‘the Arabs’ were the true offspring of this dusty and perfumed soil” or her observation: “when I walked barefoot with my brother on the hot trails of Oran, I felt the sole of my body caressed by the welcoming palms of the country’s ancient dead…” (Cixous 1998a: 153)). But they recognize these Orientalist words as French (“the word Arab belonged to French colonialism” (Cixous 1998b: 183)). Orientalism is a borrowed framework, a borrowed language, a borrowed way of speaking and thinking but not an escapable one per se. Certainly not when speaking from the place of the cut. Not when speaking of the becoming of the separation and the making of the Jew and of the Arab.[6]

For Cixous, Algeria is primarily a stage on which the colonial drama unfolds: a “perfumed theater, salt, jasmine, orange blossoms, where violent plays were staged” (1998a, 155), where “the scene was always war” (1998a: 156). And on this stage there are roles and positions: “one said: ‘the Arabs,’ ‘the French,’” everyone was forced to play “in the play, with a false identity” (1998a: 156). The colonial stage produces caricature figures. People said: “the Arabs and the French, and also the Jews and the Catholics” (1998a: 156). Names, words, identities have limited freedom on the colonial stage, and very little room for innovation. Thus we get “Fatma,” the Arab maid, the “dirty Jew,” the Frenchman, and the “little Arabs” (1998a: 164). Against this discursive, linguistic, and political fixation—the outcome of colonial administration and Orientalist imagination—but also from within it, Cixous and Derrida attempt to generate a discourse that highlights instability, fragmentation, ambiguity, and loss in the figure of the always already displaced and the always already lost: lost home, lost Jew, lost Arab, and lost Algeria. As a result, we are left with a discourse that is both more intimate and less (overtly) political than the carefully measured discourse commonly modeled on the analysis of Orientalism.

But I would like to suggest that writing from the place of the cut is an unwritten chapter in Orientalism. Said’s theory, because it insists on a macro-political notion of history and a structural analysis of binary power positions, leaves little room for nuances, differences, and liminal positions that speak from the place of the cut. It is not simply that Derrida and Cixous’s texts bring in, as it where, the missing Maghreb, or the missing figure of the (impossible) Arab Jew and thus complicate an otherwise more coherent, binary formulation of colonial power. It is also that, unlike the discourse of the Arab Jew, developed for example in the writings of Albert Memmi (not just in La statue de sel but in his later essays such as “Who is the Arab Jew?”),[7] Derrida and Cixous’s Arab Jew is not so much a figure (an ethnic figure), but the theoretical elaboration on the production of this historical figure as an impossibility brought about by colonialism and Orientalism. A melancholic underlining precondition that runs through the Orientalist discourse and remains both key to the Orientalist dualistic imagination and invisible in its centrality.

I am not suggesting that the Arab Jew is central to Orientalism, which presents a rather coherent picture of the Orient, often conflating “Arab” and “Muslim.” And yet this figure is not marginal to the text either. It is a figure that demonstrates the triangulated operation within the (Orientalist) binary imagination. Reading Cixous’s and Derrida’s impossible Arab Jew into Said’s book is not only to challenge its binary structure, criticized by many in the past (Homi Bhabhba 1994, Ali Behdad 1994, Lisa Lowe 1991). It is also to develop a different language, one whose power resides in its ambivalence and non-identitarianism. A language which certainly can sound and read as self-centered, beautified, and sublimated (perhaps too French?) but which gains its importance from its ability to speak from the cut and about the cut.

The Arab Jew here is a figure of political failure and a failed figure. And this failure itself, visited and revisited as loss, impossibility, “fertile wound” and the outcome of Orientalist imagination is also to gesture towards a different future. One that takes a leap of faith away from but also back to the binary and structured world of fantasy-making reality, which Said left us with forty years ago; a fertile ground from which to “depart (so as) not to arrive from.”

Gil Hochberg is Ransford Professor of Hebrew and Comparative Literature, and Middle East Studies at Columbia University. Her first book, In Spite of Partition: Jews, Arabs, and the Limits of Separatist Imagination (2007), examines the complex relationship between the signifiers “Arab” and “Jew” in contemporary Jewish and Arab literatures. Her most recent book, Visual Occupations: Vision and Visibility in a Conflict Zone (2015), is a study of the visual politics of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. She is currently writing a book on art, archives and the production of the future.

References

Ahluwalia, Pal. 2010. Out of Africa: Post-Structuralism’s Colonial Roots. London and New York: Routledge.

Behdad, Ali. 1994. Belated Travelers: Orientalism in the Age of Colonial Dissolution. Duke: Duke University Press.

Bhabha, Homi. 1994. The Location of Culture. New York: Routledge.

Bouteldja, Houria. [2016] 2017. Whites, Jews, and Us: Toward a Politics of Revolutionary Love. Translated by Rachel Valinsky. South Pasadena : Semiotext(e).

Chérif, Mustapha. 2008. Islam and the West: A Conversation with Jacques Derrida. Translated by Teresa Lavender Fagan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chow, Rey. 2001. “How (the) Inscrutable Chinese Led to Globalized Theory.” PMLA 116, no. 1: 69-74.

Cixous, Hélène. 1998a. “Mon algériance” (“My Algeriance”). In Stigmata Escaping Texts, 153-172. New York: Routledge.

——-. 1998b. “Stigmata, or Job the dog.” In Stigmata Escaping Texts, 181-194. New York: Routledge.

——–. [1999] 2001. An Algerian Childhood: A Collection of Autobiographical Narratives. Translated by Marjolijn de Jager. St. Paul, MN: Ruminator Books.

Derrida, Jacques. [1996] 1998. Monolingualism of the Other, or, The Prosthesis of Origin. Translated by Patrick Mensah. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Di Cesare, Donatella Ester. 2012. Utopia of Understanding: Between Babel and Auschwitz. Translated by Niall Keane. Albany: SUNY Press.

Egéa-Kuehne, Denise. 2001. “La langue de l’autre au croisement des cultures: Derrida et Le Monolinguisme de l’autre.” In Changements politiques et statut des langues: histoire et épistémologie, 1780–1945, edited by Marie-Christine Kok Escalle and Francine Melka, 175-98. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Herzog, Annabel. 2009. “‘Monolingualism’ or the Language of God: Scholem and Derrida on Hebrew and Politics.” Modern Judaism 29, no. 2: 226–38.

Hiddleston, Jane. 2010. Poststructuralism and Postcoloniality: The Anxiety of Theory. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Hochberg, Gil Z. 2007. In Spite of Partition: Jews, Arabs and the Limits of Separatist Imagination. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

——. 2016. “‘Remembering Semitism’ or ‘On the Prospect of Re-Membering the Semites.’” ReOrient 1, no. 2: 192–223.

Memmi, Albert. [1953] 1972. La Statue de sel. Paris: Gallimard. Translated by Edouard Roditi as The Pillar of Salt (Boston: Beacon Press, 1992).

Laroussi, Farid. 2016. Postcolonial Counterpoint: Orientalism, France, and the Maghreb Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Lowe, Lisa. 1991. Critical Terrains: French and British Orientalisms. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Naas, Michael. 2009. Derrida from Now On. New York: Fordham University Press.

Quayson, Ato. 2000. “Postcolonialism and Postmodernism.” In A Companion to Postcolonial

Studies, edited by Henry Schwarz and Sangeeta Ray, 87-111. Oxford: Blackwell.

Ratskoff, Ben. 2018. “Liberation Utopias: Houria Bouteldja on Feminism, Anti-Semitism, and the Politics of Decolonization.” Los Angeles Review of Books, April 5. lareviewofbooks.org/article/liberation-utopias-houria-bouteldja-on-feminism-anti-semitism-and-the-politics-of-decolonization/

Saito, Naoko. 2009. “Beyond Monolingualism: Philosophy as Translation and the Understanding of Other Cultures.” Ethics and Education 4, no. 2: 131–39.

Shohat, Ella. 2016. “Orientalist Genealogies: The Split Arab/Jew Figure Revisited.” Paper presented at the Qattan Foundation in London, November 17, 2015. Video recording available at vimeo.com/154166534.

Young, Robert. 1990. White Mythologies: Writing History and the West. London and New York: Routledge.

[1] Not everyone welcomed this intervention. And some accused the French intellectuals for “asserting their authority over Algeria” and for ignoring “hard political questions” by choosing instead to write about their personal and privileged experiences and not about colonialism and its impact on the majority of the colonized people. See for example Laroussi (2016: 65).

[2] For readings of Monolingualism see, among many others: Di Cesare 2012; Naas 2008; Saito 2009; Egéa-Kuehne 2012; and Herzog 2009.

[3] “During the war . . . the word that begins with ‘j’ was not spoken it was a forbidden, dangerous poisonous word. . . . My mother . . . never said the word Jew in the street. Naïve, she said that a J. Exorcism. Taboo” (Cixous 1998a: 156).

[4] Dhimmis are non-Muslims under protection of Muslim law. The protection was historically extended to the “Peoples of the Book” (Ahl al-Kitab), which included Jews, Christians, and sometimes Zoroastrians and Hindus. Protection, communal self-government, and freedom of religious practice were provided to dhimmis in return for tax. Dhimmis were also placed under restrictions and regulations in dress, occupation, and residence. The Senegalese riflemen (tirailleurs sénégalais) were among the many colonized peoples allured to serve in the French army during the First World War. By 1918, France had recruited some 192,000 tirailleurs from French West Africa, mostly from Senegal. It was only last year that France finally recognized a handful of these men and granted them French citizenship.

[5] At the time of writing this essay, Shohat was preparing her essay for publication but had not yet published a written version. A video recording of a talk version of the paper, “Orientalist Genealogies: The Split Arab /Jew Figure Revisited,” is available online at vimeo.com/154166534.

[6] It would be easy to do one of two things: 1. To accuse Derrida and Cixous of Orientalism. Their writings render themselves easily to such accusation. The most elaborate critique of Derrida’s Orientalism is famously provided by Rey Chow. Accounting for Derrida’s representation of Chinese writing in Of Grammatology, Chow deconstructs Derrida’s own European Orientalist approach. Derrida’s seminal text of deconstruction, she argues, orientalizes Chinese writing as an ideographic language and represents it as the West’s other, which as such escapes scrutiny. The East thus becomes represented by “a spectre, a kind of living dead that must, in his philosophizing, be preserved in its spectrality to remain a Utopian inspiration” (Chow 2001: 72). Cixous too has been blamed more than once, especially in her writings about Algeria. Farid Laroussi, for example, argues that Cixous’s very description of the Arab Jew is based on “an archaic type of Orientalism” (Laroussi 2016: 65). 2. The opposite tendency is to praise Derrida and Cixous (perhaps Deconstruction as such) for generating new ways of thinking and writing that directly challenge Orientalism, confront the superiority of the West, and disable the homogeneity of its “other,” the Orient. Since the early 1990s, several studies have emphasized the deep theoretical and political connections between deconstruction and postcolonialism. In 1990, Robert Young argued that at the heart of French deconstruction one finds “Algeria” as a postcolonial event. He famously opens his White Mythologies by proposing that “if so-called ‘so-called post-structuralism’ is the product of a single historical event, then that moment is probably not May 1968 but rather the Algerian War of Independence—no doubt itself both a symptom and a product” (Young 1990: 1). Since then, several critics have made similar arguments and connections. See, for example, Ahluwalia 2010 and Quayson 2000.

[7] In this sense these texts both continue and break away from the legacy of Albert Memmi, whose memoir The Pillar of Salt was perhaps the first to document the colonial tragedy in North Africa (Tunis in this case) through the figure of the Arab/Berber Jew as the failed figure of in-betweenness: indigenous but not quite, westernized but not enough. Memmi’s fragmented, displaced, exiled protagonist, Alexandre Mordekhai Benillouche, is a tragic anti-hero and a true victim of colonial estrangement. Several years later Memmi would publish his essay on the impossibility of the Arab Jew, “Why we are not Arab Jews,” concluding that despite the end of colonialism, the figure of the indigenous Arab Jew is not and can no longer be, a possibility. As is well known, Memmi would also become, over the years, an adamant supporter of Zionism, despite choosing to live in France himself. Both Derrida and Cixous follow Memmi’s legacy in many ways, in their own autobiographical writings about Algeria, but they break away from his determined position, replacing it with ambiguity and open-ended futures. While Memmi presents a tragic image of displacement and exile, Derrida and Cixous, each in their own way, celebrate exile, displacement and the position of the outsider (with no mother tongue and no sense of belonging) as a privileged critical position. And as a position from which colonialism may appear not as a coherent subject matter based on monolithic power binarism but as a system based on the creation and generation of differences within. For a comprehensive reading of Memmi’s novel and other writings on the figure of the Arab Jew, see my chapter dedicated to his work (Hochberg 2007: 20-43).