This article has been peer-reviewed by the b2o editorial board.

by Emma Lezberg & Christian Thorne

Literary theorist Ursula Heise and novelist Amitav Ghosh share a vision for contemporary fiction: they both consider it crucial that narrative, in an age of intensified interconnection, address global concerns.[1] Heise asks how art can “foster an understanding of how a wide variety of both natural and cultural places and processes are connected and shape each other around the world, and how human impact affects and changes this connectedness” (Sense of Place 21). Ghosh specifies Heise’s request: where will we find the tools to write about climate change on the scale the problem demands?

Both Heise and Ghosh, as Heise herself notes, are picking up the inquiry Fredric Jameson raised decades ago: both are, we might say, searching for a way out of postmodernism. Jameson identifies a certain problem generated by late capitalism: “the incapacity of our minds, at least at present, to map the great global, multinational and decentred communicational network in which we find ourselves caught as individual subjects” (“Postmodernism and Consumer Society” 16). Our lives are increasingly shaped by global processes inaccessible to our senses. Yet Jameson argues that our artistic moment is characterized precisely by its inability to make sense of the world-system as a whole:

[T]he phenomenological experience of the individual subject—traditionally, the supreme raw materials of the work of art—becomes limited to a tiny corner of the social world, a fixed-camera view of a certain section of London or the countryside or whatever. But the truth of that experience no longer coincides with the place in which it takes place. The truth of that limited daily experience of London lies, rather, in India or Jamaica or Hong Kong[.…] Yet those structural coordinates are no longer accessible to immediate lived experience[…]” (“Cognitive Mapping” 349)

This contradiction, Jameson concludes, “poses tremendous and crippling problems for a work of art” (“Cognitive Mapping” 349). In order to deal meaningfully with London, India, Jamaica, and Hong Kong in a single work and reveal the links between them, aesthetic representations would need to achieve some innovative reconciliation of subjective experience with structural reality.

Heise and Ghosh are among the only theorists of the novel to rise to Jameson’s challenge, ingenuously and at face value. They diverge, however, around the innovations they would recommend. Ghosh, indeed, isn’t sure whether there is anything to recommend. He pegs the alarming absence of climate-change fiction on the mechanics of fiction writing itself. Settings in literature, Ghosh writes, are “constructed out of discontinuities” in such a way that “connections to the world beyond are inevitably made to recede” (59). Yet “the earth of the Anthropocene is precisely a world of insistent, inescapable continuities, animated by forces that are nothing if not inconceivably vast” (62). Our literary techniques thus seem ill-suited to address our contemporary world.

A specification is in order. It is the realist novel that Ghosh is holding up for inspection and that he finds wanting, for he agrees with Margaret Atwood that “the Anthropocene resists science fiction: it is precisely not the imagined ‘other’ world apart from ours” that demands our attention, nor are problems like climate change “located in another ‘time’ or another ‘dimension’” (72-73). At this last statement, Heise balks, for it is precisely the “speculative approaches” that she believes will make possible a global storytelling. She thinks Atwood and Ghosh “fundamentally misunderstand the ‘elsewheres’ of science fiction,” which Jameson himself has argued are simply our own world presented as “the past of a future yet to come,” something readers “have no trouble” recognizing (Heise, “Climate Stories”). If this is true, then Heise sees no reason to look elsewhere. If science fiction “satisfactorily addresses the challenges of narrating the Anthropocene,” with “[n]one of the constraints” of conventional novels, “why should we care whether the mainstream novel does” the same (Heise, “Climate Stories”)?

In this essay, we will not take a stance on the accomplishment of science fiction. We do believe, however, that the realist novel deserves a second chance, if only because cognitive mapping is what social realism has always promised to deliver: novels of totality and interconnection, novels that map extensive sociohistorical networks and reveal the animating connections between points. Admittedly, the totalities that the Lukácsian novel maps—the “worlds” of a Balzac, Tolstoy, Scott, or Cooper—are not properly worlds at all. Indeed, one need only become minimally acquainted with Lukács to notice that he deploys the words “totality” and “nation” all but interchangeably (The Historical Novel). Yet when Heise writes that allegory is “hard to avoid in representations of the whole planet,” does she really mean that it is impossible—that allegory is obligatory (Sense of Place 21)? If one seeks a contemporary literature that engages with the world, it does seem worth examining whether it can do so in a fashion continuous with ordinary experience, and not just in disguise.

One way forward is to examine the merits of a particular genre within realist fiction, one that appears well-suited for expanding the geographical scope of the novel beyond the cities and nation-states of the novel tradition: immigrant fiction, that signature genre of the last half-century claiming transnational migration, and thereby the linkages between states, as its very subject.[2] Instead of shrinking the world to fit into the London neighborhood already in the camera’s frame, why not move the camera or indeed buy a wider lens? Instead of forcing the Thames to stand in for oceans, why not cross actual oceans? Just as the Lukácsian protagonist mediates between parties in a historical conflict, revealing the forces that underlie a moment in national history, so the migrant could perhaps mediate between nations, as neo-Waverley, disclosing at least part of the structure underpinning multinational capitalism (The Historical Novel).[3] We should not, admittedly, expect immigrant fiction to deal with the entire world-system: the immigrant journey is generally only two-term, and the world-system clearly has more nodes than that. But even a two-term journey would deal not only transnationally but also relationally; unlike travel fiction, to name a close cousin, which tends to represent nations additively, as a mere list, immigrant fiction would likely be interested in transnational connections. In addition, the immigrant is often departing a lower-income or peripheral country for a wealthier country in the old imperial core, and this should enable the immigrant novel to represent not just any transnational relationship but a tellingly uneven one, revealing conditions of global dominance that characterize our world-system. A question poses itself: might this genre remedy the crisis of contemporary narrative that Heise and Ghosh have articulated, and might it do so without relying on full-blown allegory?

In 1981, William Boelhower offered an early account of the genre’s narrative structure, proposing the following as its “macroproposition” (4): “An immigrant protagonist(s), representing an ethnic world view, comes to America with great expectations, and through a series of trials is led to reconsider them in terms of his final status” (5). The novels, he contends, revolve around three structural moments: Expectation, Contact, and Resolution, each taking America as its focus. The Expectation is of the New World, the Contact is with the New World, and the Resolution—the protagonist’s “final status”—is a settlement with New World society, usually in the form of assimilation (5).[4] To this extent at least, the setting of Boelhower’s immigrant novel is America, with the Old World featuring mainly through the protagonist’s “ethnic world view”—by which he seems to mean a set of non-American attitudes and dispositions.

But Boelhower’s theory is in many respects outdated, as contemporary authors have sought to question and complicate a mass readership’s likely assumptions about the immigrant experience. Boelhower notes that it is “essential[…]that the protagonists be foreign-born” (6), while many of the most lauded immigrant novels written since[5] take as their protagonists children of immigrants, not immigrants themselves. He insists that “[t]he reasons for immigrating[…]are expressed in all immigrant novels and are an essential part of the narrative model” (Boelhower 6), even though in contemporary narratives—as we will see later—the protagonist’s ignorance of his family’s, and sometimes even his own, immigration history is often an crucial point. In many recent immigrant novels, the stage of “Expectation” is heavily downplayed or denied completely; characters begin the novel already disillusioned with America, not expecting all that much.[6] And it is also not the case that all contemporary immigrant novels allow America to monopolize their settings. There is a considerable amount of variety on this front, among which we can draw one core distinction: those set (almost) exclusively in one country, and those that opt for multiple settings in more than one nation.

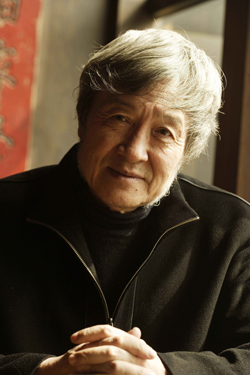

One important type of immigrant novel, therefore, takes place in the destination country: Tortilla Curtain by T.C. Boyle, The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri, Native Speaker by Chang-rae Lee, White Teeth by Zadie Smith, The Beautiful Things that Heaven Bears by Dinaw Mengestu, and Call it Sleep by Henry Roth, to name a few.[7] Many of these novels excel at uncovering the workings and contradictions of metropolitan (American or British) society. Native Speaker, whose Korean-American protagonist—the child of an immigrant—assists on a politician’s campaign, expertly exposes the underlying racial tensions in New York City. Tortilla Curtain—following a destitute undocumented couple and a middle-class native-born couple living in the same suburb of Los Angeles—puts immigration-related tensions into stark focus, revealing the xenophobia and racism lying just under the surface of most “liberal” American towns. The protagonist in The Beautiful Things that Heaven Bears says himself how important it is to consider his city, D.C., “not in fragments or pieces, but as a unified whole” (Mengestu 173). That is a novel proclaiming its Lukácsian intentions in maximally quotable form.

Yet these novels exclude the country of origin from the narrative in myriad ways. Boelhower had pointed out that “[a]lthough there is usually a clear journey sequence in the immigrant novel[…]it may be present as a flashback or a digression” (6). Contemporary immigrant novels are less likely to include such a sequence, in flashback or not, and they tend to open after the immigration has already taken place. This brings us to a strange and altogether counterintuitive realization: immigrant novels tend to erase, or at least bury, the very migration—the very interstitial, transnational connection—that nominally defines the genre. In this way, the immigrant narrative is reduced to the assimilation narrative (which is sometimes a failed assimilation narrative); the immigrant’s story begins when he disembarks from the plane or when she crosses the border. This aligns, of course, with America’s idealized conception of the immigrant-with-no-past, who sheds her history and is reborn in a new land.[8]

Because these novels commence after the journey, narrative time spent in the country of origin tends to be minimal, and details sparsely shared. Some do not feature the country of origin at all, as in Native Speaker, whose protagonist, Henry, has never left the United States and has heard little about Korea from his parents. We never read his parents’ backstory—Henry himself “never learned the exact reason [his father] chose to come to America,” and only heard his father mention “something about the ‘big network’ in Korean business, how someone from the rural regions of the country could only get so far in Seoul” (Lee 57)—nor are we let into the pre-history of his family’s immigrant housekeeper or his father’s old friends who come to visit.[9] Tortilla Curtain, which features two migrant protagonists, is nevertheless similar in this respect: the novel opens several weeks after the undocumented couple has reached America from their native Mexico, and all we hear about the latter is one mention of the country’s forty percent unemployment rate (Boyle 199), a few remarks on men going north for migrant work (see 50, for example), and a couple of tightly drawn vignettes: the wife’s father killing an opossum (20), for example, or villagers firing pistols at the sky during a bad storm (129-130). We see this same pattern in Call it Sleep, which begins with the immigrant protagonists disembarking in America. Europe, their point of origin, is “the other side” (Roth 10), a “world somewhere, somewhere else” (23), and although the child narrator, David, thinks “[a]nything about the old land was always worth listening to” (33), we nevertheless rarely overhear these conversations with him. There are moments when “[c]onversation touched on many subjects[…]from this land to the old land and back again to this,” but the reader is sent away from the table (Roth 31). When David’s father tells him that he ate cornmeal as a child, David remarks that “that was one of the few facts that David had ever learnt of his father’s boyhood” (Roth 209). And when David’s mother finally tells an extended story of her young adulthood prior to her immigration, most of it is in Polish and therefore incomprehensible to David, and not transcribed for us (Roth 194-204).

This reluctance to cross oceans and borders extends even to a number of immigrant novels whose characters travel back to their home countries. Here we can look to White Teeth and The Namesake as two striking examples. White Teeth might give us hope for a binational mapping, as one of the novel’s fathers sends his son, Magid, to live for years with his extended family in his native Bangladesh; the omniscient narrator head-hops between characters and ranges widely in time and space; and the book has the trapping of a family saga, tracking three generations of characters. The narrator briefly follows Magid across the ocean to make the point that Magid in Bangladesh and his twin brother in England are cosmically connected (“tied together like a cat’s cradle,” to be precise: both boys narrowly escape very different kinds of disasters at exactly the same time, halfway across the world (Smith 220)), which gives us only more reason to expect that the novel might follow both boys. And yet, even with all indications pointing to Bangladeshi interludes in White Teeth, Magid, after that one paragraph, disappears from the narrative for his eight years abroad, our only knowledge of him coming from the letters he sends to his parents—until he finally returns to London, at which point the narrator promptly regains interest in his story and begins inhabiting his mind fairly extensively. The only time the narrator travels beyond England is in brief flashbacks of Samad, Magid’s father, and his friend Archie during World War II, serving in Greece and Bulgaria (for the longest series of flashbacks, see Smith 83-122). At the end of the novel, we are told that Irie, her husband Joshua, and her grandmother Hortense will visit Jamaica, Hortense’s birthplace, yet all we get are the words, “a snapshot seven years hence of Irie, Joshua, and Hortense sitting by a Caribbean sea” (Smith 541); the novel declines to so much as describe the snapshot to which it alludes.

The Namesake, like White Teeth, also enjoys an omniscient narrator that inhabits the minds of both immigrants and their children. It, too, concerns itself with tracing effects back to their causes. The novel opens eighteen months after a Bengali couple has immigrated from Calcutta, India to Cambridge, Massachusetts, but, when the wife’s mother dies, the couple boards a plane with their infant son, about to fly “for the first time in his life across the world” for the funeral (Lahiri 47). Yet when we flip the page to the next chapter, we do not find ourselves across the world. Instead, the narrative has jumped forward two years, skipping their visit to Calcutta entirely. We are told that the family henceforth visits Calcutta every few years, “six or eight weeks passing like a dream” each time—but for the reader, passing in this one sentence (Lahiri 64). By the time the son, Gogol, is ten years old, “he has been to Calcutta three more times,” yet all we are told is his astonishment at seeing so many Gangulis—his last name—in the telephone book (Lahiri 67). Later in the novel, the narrative does follow the family to Calcutta on the husband’s sabbatical. Yet the eight months pass in less than eight pages. Gogol finds it impossible to keep up with cross-country training on the congested streets, so he “surrender[s] to confinement,” which means that we learn much more about the relatives’ households than we do about the postcolonial city of four million around him (Lahiri 83). Later, when his girlfriend’s mother asks Gogol, “What’s Calcutta like? Is it beautiful?”, the question takes him by surprise: “He is accustomed to people asking about the poverty, about the beggars” (Lahiri 134). Yet we readers were never shown the beggars or introduced to the poverty; we learned little more than that the weather is warm and that people sleep under mosquito nets. Tellingly, although the word “world” comes up frequently in the novel, it consistently refers to some much smaller totality: a nation, an ethnic group, or even just a campus.[10]

At the very least, then, we can conclude that a good many immigrant novels do not provide the multinational mapping for which Heise is looking. Myriad strategies combine to render the Old World beyond narration. The novels commence after the characters have left it behind. Protagonists, especially those who are children of immigrants or were young when their families emigrated, may be genuinely ignorant of it. References to it, even if numerous, are vague, cloaked in nostalgia or distant generalities. If the characters travel, whether in flashback or in the main narrative, time is condensed into brief recaps, and we manage to learn disproportionately little about it. We can attribute this at least partially to the psychologizing impulse of many of these novels: even when the narrative brings us to Calcutta, say, it focuses on the characters’ minds rather than the city that surrounds them. For all these reasons, these narratives neglect to bring the other country into analytic view, running dry when they might otherwise turn transnational. They may take from the realist tradition a certain appetite for sociohistorical explanation, but this appetite does not extend overseas. The Beautiful Things that Heaven Bears astutely sums up the position in which these novels find themselves: the protagonist used to be able to keep both the Ethiopian and the American calendars in his mind, but “as the years accumulated, it became harder and harder to remember that there were two halves to the narrative” (Mengestu 153).

One might protest that a novel need not have an expanded setting to deal with expansive forces. Why can global dynamics not be adequately addressed “from the scale of a single neighborhood” (Kirsch 25)?[11] Yet the pattern these novels reveal should caution us against such an approach. These immigrant novels—with circumscribed settings that are, as Ghosh suggests, “constructed out of discontinuities” (59)—tend to make intelligible only the effects of global forces and movements, leaving their causes mysterious. Forces originating outside that spatial scope, such as the forces that led these characters to immigrate, become mere events, mere “things that happen,” without explanation—which then turns every Old Country into the same narrative abstraction that requires no specification, the black box for which lonely immigrants pine and to which an occasional twin brother can indefinitely disappear.[12]

This is a point worth pausing on, for we must make clear that these immigrant novels do not erase the country of origin, however much they bury it. Quite the contrary: the Old World tends to loom quite large, determining much more in the narratives than merely Boelhower’s “ethnic world view.” In White Teeth, it is on Bangladesh that Magid’s father pins all his hopes for his son, and it is Jamaica that persistently occupies the imagination of Irie, the daughter of a West Indian immigrant, in the second half of the novel. In The Namesake, Bengal comes up constantly even when the story hunkers down in the United States: we hear mention of the snacks sold on Calcutta sidewalks (Lahiri 1), the tea sold on Bengali trains (112), the funerals performed for Bengal’s dead (70). In The Beautiful Things that Heaven Bears, the protagonist and his two friends, all immigrants from Africa, play the “coup game” to the point of obsession—I name the leader of an African coup, you guess with which country he is associated (see Mengestu 7, for example); the protagonist “searche[s] for familiarity” and catches “glimpses of home” everywhere in D.C. (Mengestu 175-76), and his friend is similarly wont to see “flashes of the continent wherever he went” (100). But insofar as the country of origin occupies a prominent place in the narrative, it does so as a suspended question mark, a skeptical gap, an absent cause, inserted only to prevent causal regress. A familiar smell here, the name of a politician there—but no sense of the larger society and how these isolated details fit together. The eight-month trip to Calcutta is “quickly shed, quickly forgotten[…]irrelevant to their lives” (Lahiri 88).[13] Jamaica is a “blank page”—“somewhere quite fictional” (Smith 400, 402). Ethiopia, though it is the country that nursed him, seems “conjured, the fictitious dreams of a hyperactive and lonely imagination” (Mengestu 96). We know the country of origin is important, that it is where the story really began, but it is not accessible to us—because even if the characters grew up there, even if they return occasionally to visit, it is no longer truly accessible to them.

These narratives, therefore, tend perhaps unexpectedly to announce and problematize their own self-imposed limits. We might, in this sense, venture to call these immigrant novels postmodern, in that they self-consciously draw attention to—and then fail to resolve—the epistemological crisis Jameson has identified. Tortilla Curtain says explicitly that “it was crazy to think you could detach yourself from the rest of the world” (Boyle 32)—yet the rest of the world is nevertheless unreachable. In Native Speaker: “no one is smart enough to see the whole world. There’s always a picture too big to see” (Lee 46). In White Teeth: characters feel “tiny and rootless,” with miniscule “significance in the Greater Scheme of Things” (Smith 11)[14] and yet with the dream to “make sense of the world” (366). And without getting too far ahead of ourselves, we can say that slogans such as these will appear even in immigrant novels that feature the home country more substantially, though we cannot yet say whether those do more to resolve the dilemma than these do. In The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao: “The world! It was what she desired with her entire heart, but how could she achieve it?” (Díaz 113) In The Russian Debutante’s Handbook: he “considered yet again his own relative loss of place in this world” (Shteyngart 408). In Americanah: “She felt like a small ball, adrift and alone. The world was a big, big place and she was so tiny, so insignificant” (Adichie 190).

This crisis of mapping is not only articulated on the geographic front, as an inability to locate the subject in space, but also on the historical front as an inability to locate the subject in time. We see this most prominently in the genre’s metaconcern for storytelling: of the twelve immigrant novels referenced in this essay, chosen because high-profile, eight include major characters (and five feature protagonists) who are writers or professors.[15] Characters are maddened by their inability to tell a story in its totality, a story of totality: “if you’re looking for a full story, I don’t have it” (Díaz 243); “my point is that this is not the full story.[… F]ull stories are as rare as honesty, precious as diamonds” (Smith 252); “There’s more to the story. There always is to a true story” (Alvarez 102); “You understand I am collapsing all time now so that it fits in what’s left in the hollow of my story?” (Alvarez 289); his “problem” is that “he wanted to tell the entire history of the Congo,” believing that “[n]othing can be left out” and that “[t]he poem must be able to contain it all” (Mengestu 170-71). Beginnings and endings of the tales these characters tell are self-consciously artificial and vexed: “the question is how far back do you want? How far will do?” (Smith 83); “this is no movie and there is no fucking end to it, just as there is no fucking beginning” (Smith 464); “maybe I should start there[…o]r is this where the story begins[?]” (Mengestu 127); “the end is simply the beginning of an even longer story” (Smith 540-41). In certain cases, this inability to find The Beginning is explicitly glossed as the inability to access the home country: for example, “the particular magic of homeland, its particular spell over Irie, was that it sounded like a beginning. The beginningest of beginnings” (Smith 402), only to be followed up a few pages later with, “if you could take them back to the source of the river, to the start of the story, to the homeland… But she didn’t say that, because[…]it was as useless as chasing your own shadow” (Smith 407). And narrators meditate on the force that “sphinxes[…]all attempts at narrative reconstruction” (Díaz 243), most memorably with The Russian Debutante’s Handbook’s assertion that “You’ll need three omniscient narrators to cobble together half a narrative” (Shteyngart 364). In all these ways, the novels routinely reflect on their own fabrication and their own restraints. And as an additional layer of self-awareness, several of the novels that may prove best at transnational mapping—Oscar Wao, Americanah, and The Russian Debutante’s Handbook—mention postmodernism explicitly and, in the last instance, treat it as a major narrative concern.[16]

Which brings us, then, to the second type of immigrant novel: those that do engage forthrightly with multiple regions on the globe. These are novels like Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Garcia Girls by Julia Alvarez, No Telephone to Heaven by Michelle Cliff, Breath, Eyes, Memory by Edwidge Danticat, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Díaz, and The Russian Debutante’s Handbook by Gary Shteyngart. Nearly all allow us inside multiple characters’ heads and refuse neatly linear narratives.[17] All are told looking back on events at a delay and are self-conscious about the mediated nature of their tales. And all show their protagonists crossing oceans—in fact, all do so more than once—and spend significant narrative time in one or more countries in addition to the U.S. That first set of immigrant novels proved consonant with classical social realism: a realism of one nation, in which the rest of the world registers only as narrative uncertainty. This second set, by contrast, successfully brings at least two remote locations into view, and thus has the potential, at least, to make intelligible the lopsided relationships that characterize our global order. Yet at least three problems persist—and we will want to examine them carefully.

First, in expanding geographic scope to include multiple locations, some end up slackening the demands of realism in each. We can see this in particular with Danticat’s Breath, Eyes, Memory, which follows its protagonist, Sophie, from Haiti to America and back again for an extended visit. Haiti is viscerally present—beggars, prostitutes, soldiers, bribes (for example, Danticat 228)—in a way that Mexico or Bengal or Jamaica in the novels described above are not. Yet consistently, the narrative brings up some highly-charged political event that is clearly the symptom of a larger process, but, rather than broadening its scope to bring the structure into view, immediately narrows its focus instead to the psychological or the familial. For example, right before Sophie will join her mother in America, the narrative describes in gory detail what seems to be a government crackdown on a student protest. We are provided no context or explanation—and when her aunt yanks her to safety and asks, “Do you see what you are leaving?”, Sophie merely replies, “I know I am leaving you” (Danticat 34). Danticat may want us to feel the confusion of the child narrator in this moment, but when Sophie returns to Haiti as an adult and a friend comes running to tell her that the macoutes, the dictator’s militia, killed a villager, we are once again not given any context for this state violence. Instead, the sobbing friend declares, “That’s why I need to go [i.e. emigrate],” and Sophie’s grandmother voices the exact pattern we are noticing: “A poor man is dead and all you can think about is your journey” (Danticat 138).[18]

We see this pivot to the micro scale even more strikingly when we are allowed to listen to a group of Haitian-American men “talking politics” (Danticat 54). Their argument mentions such topics as the Haitian konbit system, Vietnamese refugees resettled in the United States, and America’s military intervention in Haiti in the early twentieth century. Yet the exposition that follows does not explain what the konbit system is, who the “boat people” are, and what the military occupation entailed and why it was undertaken—the last of which, especially, has mighty relevance for the dynamics the characters face. Instead, the narrator interjects, “For some of us, arguing is a sport,” before going on to describe the “colorful language” used in the marketplace in Haiti and the dynamics between Sophie’s mother and her mother’s boyfriend (Danticat 54). The novel collides with loaded and wholly pertinent transnational phenomena only to bounce elsewhere.

Danticat has written what has deservedly become known as one of the most ambitious and powerful narratives on the Haitian-American immigrant experience, and her deprioritization of extended narration and structural exegesis—which, no less than sociological analysis, would require embedding “individual biography in the larger matrix of culture, history, and political economy” (Farmer 41)[19]—may be precisely what enables her relatively short novel to so masterfully trace the impacts of trauma across oceans and generations. But this does leave her treatment of both Haiti and America only lightly ethnographic, and the countries are distinguished almost exclusively by which important people in Sophie’s life happen to live in each.[20] A reviewer credits Danticat with “evoking the pace and character of Creole life, the feel of both village and farm communities” (“Breath, Eyes, Memory”). Precisely: a pace, a feel, but not a network. She gives us a sense of how life in both places is lived but chooses not to probe the underlying mechanisms of the societies, even when the plot invites or even, in certain instances of state violence, begs for explanation—for significantly, Danticat does not avoid bumping up against such topics and thus indicates their relevance to the story she is telling, making the reader aware of the limits the novel is hitting. We need not follow Heise in her search for novels that map transnationally, but if we do, we should recognize that while the first group of immigrant novels we examined mapped but were not transnational, this novel, though transnational, is not particularly interested in mapping.

A second impulse in these novels that resists transnational mapping is what we can call “split-screen” realism. Garcia Girls exemplifies this tendency. Alvarez’s novel backtracks chapter by chapter in narrative time from the Garcia sisters’ adult lives in the United States to their childhood in the Dominican Republic—and in between, their hasty emigration from the D.R. when their father’s plot against the government is suspected. The novel examines America only scenically (as in Breath, Eyes, Memory), but when the setting moves to the Dominican Republic, we not only get a sense of the fear Trujillo and his SIM elicit but also how the dictatorship goes about its business: its method of interrogating children and servants first, for example, and the way SIM agents can be intimidated by “big men” with American connections. The novel applies a realist impulse to multiple nations—is this not what we have been looking for?

Not quite, in fact. Our hope was to find a novel that transcended the horizon of the nation: that zoomed out to view each country as a node in a larger global network. What it seems that Garcia Girls has given us instead is multiple distinct networks, each still delineated by national boundaries and tied together only by the sisters’ journey. We are missing the connections between nations. It is surprising for a novel concerned equally with the United States and the Dominican Republic to not once mention the D.R.’s occupation by U.S. forces, Trujillo’s training with the U.S. Marines, or any of the numerous incidents involving both countries that occur within the novel’s narrative time (1989-1956): Trujillo’s abduction of Jesús Galíndez in New York City, rumors of CIA involvement in Trujillo’s assassination, or (especially) the second U.S. invasion of the island in 1965. The sole connection, alluded to only once, is the uncle’s job as a CIA agent organizing against Trujillo (“his consulship is only a front—Vic is, in fact, a CIA agent whose orders changed midstream from organize the underground and get that SOB out to hold your horses, let’s take a second look around to see what’s best for us” (Alvarez 217)), which raises all sorts of questions the novel chooses not to answer: How did Vic gain that position? Who changed his orders? Why is the CIA involved in the first place? Instead of examining the relationship between the U.S. and the D.R.—one characterized by a vast power imbalance, and one in which the global struggle between capitalism and communism dictated many terms—the novel considers the sisters’ journey as a migration between one network and another, not between nodes in one total network. Alvarez has provided us not with a mobile camera, but with two fixed cameras, each with national scope.

Finally, a third problem: while “split-screen” novels like Garcia Girls seem uninterested in mediation, other novels, like Shteyngart’s The Russian Debutante’s Handbook, are perhaps overly stuck on mediation. A prerequisite for mapping a society—and Lukács is especially keen on this point—is that the protagonist must bring different parts of society into human contact (The Historical Novel). The character must leave abuela’s kitchen and become acquainted with individuals from different backgrounds, classes, and affiliations—which might help explain why so many classically realist immigrant novels focused on America bring a wealthy, native-born WASP family into close proximity with the immigrant protagonist,[21] and one reason why a novel like Breath, Eyes, Memory does not map: the protagonist spends almost the entire book in one of three houses, and both Haiti and America become defined more by the people who happen to live there than by sociopolitical characteristics of the nations at large.[22] In The Russian Debutante’s Handbook, we do get an initial description of Prava when the protagonist Vladimir tours: we see the quarters of the city, the smokestacks, the Austrian bank and German car dealership, and The Foot, the remains of an enormous statue to Stalin. Yet because of Vladimir’s assignment to cheat Prava’s expats in a Ponzi scheme, most of the characters we meet in the city are American expats. In fact, the only exception might be the babushkas, the old women protesting around The Foot. Vladimir, newly arrived in Russia, remarks to an acquaintance, “I’m still a little out of it as far as the locals go.” The friend’s reply? “Forget about them.[…] This is an American town” (Shteyngart 204).

Thus, although Vladimir spends 300 pages narrating how this miniature society functions, what we miss entirely is the rest of Russian society; we finish the novel with the impression that Prava is populated solely by thugs, expats, and a few old ladies still quoting Marx. The impulse to map is there, but the subject proves elusive: Shteyngart is so preoccupied with the bridge that he neglects the land on one side of that bridge, and so his efforts to represent this transnational connection actually detract from his engagement with Russia. The Russia we find is also quite stereotyped: to be “russified” in Shteyngart’s telling is to add gunfire, car alarms, and a red carpet (Shteyngart 178). Along the lines of the immigrant novel’s postmodern character, we might even say that The Russian Debutante’s Handbook provides not a map of Russian society but a pastiche of a map, endowing the Russian present “with the spell and distance of a glossy mirage” (Jameson, “The Cultural Logic” 21). In both these ways, Russia is pushed to the margins. This results in an unexpected universalizing of the novel’s Russia: the Emma Lazarus Immigrant Absorption Society in New York City is once referred to as “that nonprofit gulag” (Shteyngart 107), and an immigrant early on in the novel insists to Vladimir, “Everywhere is Russia.[…] Everywhere you go…Russia” (10). But more generally, as the above remark about the “American” town suggests, we can track an equating of the First, Second, and Third Worlds in all directions: the immigration office is likened on the first page of the novel to a “sad Third World government office” (Shteyngart 3); later, a barkeep in a Soviet town speaks “in near-perfect English, as if the waves of the Pacific were stroking the sands of Malibu outside” (417-18).

We can see, then, that most immigrant novels do not provide anything like the global representation for which Heise, Ghosh, and Jameson are searching. Yet a few immigrant novels do avoid all of these tendencies, revealing how the narrative theme of immigration can—even if it does not always—enable realism to map at scales larger than the nation. Adichie’s Americanah offers a multiplot that follows one character from Nigeria to America and back and a second from Nigeria to England and back, while also delving deeply into issues of race, gender, and class in each nation; including detailed conversations about transnational connections (such as visa applications, rich Americans giving charity to African countries, and asylum seekers crossing into Europe); and, despite the title of the novel, never allowing the expat community to crowd out Nigeria.[23] Cliff’s No Telephone to Heaven, in which Clare travels from Jamaica to America to Europe and back to Jamaica, draws up a network of various characters connected to one another across the world; examines postcolonialism in Jamaica, Jim Crow in America, and the National Front in London; and is interested from the start in how, say, the guns used by Jamaican militants were made in America and the ganja they are growing will be exported to America. And Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, which follows Oscar and his family back and forth between the Dominican Republic and the United States, begins with the fukú curse that connects generations and continents; has Oscar meet Dominican individuals across social strata (most memorably, the prostitute with whom he falls in love); and includes not just exposition that functions as internal footnotes, but actual footnotes—snarky and engaging—on Dominican, and Dominican-American, politics.

We can track several patterns in these exemplars at the level of content. First, as we have discussed earlier, they all narrate a substantial period prior to immigration, which helps avoid an erasure of the home country. Second, they all follow multiple characters—each partner in a couple in Americanah, several generations in a family in Oscar Wao, or a whole network of family members and acquaintances in No Telephone to Heaven—which grants the novel easier access to multiple locations and multiple journeys.[24] Finally, all feature returnees: protagonists who immigrate and end up, by the novel’s conclusion, back in their countries of origin.[25] These protagonists reject the assimilation that, in other immigrant novels, threatens to crowd out the journey, and they can arrive at each shore with the fresh and pseudo-objective perspective of a stranger, which may encourage reflection on the inner workings of the societies. These novels are, paradoxically, in their own way anti-immigrant, steeped in misgivings about the purported terminus of the immigrant journey and ultimately rejecting it. Yet if they are not immigrant literature proper, we can call them migrant literature, which “focus[es] on characters for whom America is a stage of life rather than a final destination” (Kirsch 62). This makes clear the distinctive potential they hold: with America limited to one stage among several, the rest of the world has room to come into view.

These, then, seem to be the novels we have been looking for. Yet one major complication remains, one more deep-rooted and structural than the others—revealing perhaps less about the internal limits of these novels than about the onerous, perhaps even excessive, demands of the cognitive mapping project itself. We can approach this final hurdle by way of a puzzle in Oscar Wao.

Near the end of Díaz’s novel—after the narrator has provided us footnote after footnote, after the characters have traveled back and forth between the Dominican Republic and the United States, after we have followed three generations and come to see the continuities—we find Oscar on a visit to Santo Domingo. Under the heading “Oscar Goes Native” comes one sentence that takes up almost three pages. It is too long to cite in full, but we would not do it justice if we did not quote a substantial length. Here, then, are some excerpts:

After his initial homecoming week, after he’d been taken to a bunch of sights by his cousins, after he’d gotten somewhat used to the scorching weather and the surprise of waking up to the roosters[…]after he refused to succumb to that whisper that all long-term immigrants carry inside themselves, the whisper that says You do not belong[…]after he’d given out all his taxi money to beggars and had to call his cousin Pedro Pablo to pick him up, after he’d watched shirtless shoeless seven-year-olds fighting each other for the scraps he’d left on his plate at an outdoor café[…]after a skeletal vieja grabbed both his hands and begged him for a penny, after his sister had said, You think that’s bad, you should see the bateys[…]after he’d gotten somewhat used to the surreal whirligig that was life in La Capital—the guaguas, the cops, the mind-boggling poverty, the Dunkin’ Donuts, the beggars, the Haitians selling roasted peanuts at the intersections, the mind-boggling poverty, the asshole tourists hogging up all the beaches, the Xica de Silva novelas where homegirl got naked every five seconds that Lola and his female cousins were cracked on, the afternoon walks on the Conde, the mind-boggling poverty, the snarl of streets and rusting zinc shacks that were the barrios populares, the masses of niggers he waded through every day who ran him over if he stood still, the skinny watchmen standing in front of stores with their brokedown shotguns, the music, the raunchy jokes heard on the streets, the mind-boggling poverty[…]—[…]after he stopped marveling at the amount of political propaganda plastered up on every spare wall — ladrones, his mother announced, one and all — after the touched-in-the-head tio who’d been tortured during Balaguer’s reign came over and got into a heated political argument with Carlos Moya[…]after he’d seen his first Haitians kicked off a guagua because niggers claimed they “smelled,”[…]he decided suddenly and without warning to stay on the Island for the rest of the summer with his mother and his tío. (Díaz 276-78)

Oscar seems to be doing for Santo Domingo what a reader with a taste for realism might wish the children in The Namesake had done for Calcutta: leave the family home and uncover the economic, political, and cultural dynamics of the city for us. Yet this is not, in fact, explanatory narration, and may not be narration at all, but rather its opposite: the chaos of unmediated subjective experience whirling around Oscar without offering the tools to make sense of it all. The sentence drags on, with enough repetition, that the reader might start to think, I get it already! Yet Díaz is insisting that we do not get it. The poverty of La Capital remains “mind-boggling” even after seeing it many times. Oscar, and we, cannot wrap our minds around it—cannot, we might say, cognitively map it. The repetition unto excess is a symptom of maplessness.

But Díaz has provided us with enough context—on the Trujillo regime, on corruption, on U.S. intervention—to be able to account for the poverty in Santo Domingo. The narrative, judged on its own terms, should have little trouble incorporating this sight into the network it has succeeded in drawing up. Oscar, too, knows much of the information we now do: the opening footnote of the novel begins, “For those of you who missed your mandatory two seconds of Dominican history,” implying that the Dominican-American characters know much more than the reader on topics such as this (Díaz 2). So why should the poverty be mind-boggling, either to us or to him? Is it not precisely what we would expect to see, understanding the history and politics Díaz himself has taught us? Either the novel, after achieving an unusually ambitious feat, is professing not to have done so, thus perplexingly selling itself short and denying its own accomplishment; or, alternatively, it is professing that the very feat—the elucidation of global connections—is itself an insufficient one. The task itself, as challenging as it may be, is somehow not ambitious enough.

And it is here, with this mind-boggling repetition of “mind-boggling,” that Díaz helps us to notice something unsettled even in Jameson’s prose, and perhaps to clarify Jameson’s project. Jameson begins his essay on cognitive mapping by advocating a return to the “pedagogical function of a work of art” (Jameson, “Cognitive Mapping” 347). Yet elsewhere in his writing, he makes clear that he is not looking for didacticism. Drawing on Althusser’s distinction between science and ideology, Jameson states:

The existential—the positioning of the individual subject, the experience of daily life, the monadic “point of view” on the world to which we are necessarily, as biological subjects, restricted—is in Althusser’s formula implicitly opposed to the realm of abstract knowledge.[…] What is affirmed is not that we cannot know the world and its totality in some abstract or “scientific” way[…]but merely that it was unrepresentable, which is a very different matter. The Althusserian formula, in other words, designates a gap, a rift, between existential experiencewa and scientific knowledge. Ideology has then the function of somehow inventing a way of articulating those two distinct dimensions with each other. (Jameson, “The Cultural Logic” 53)

Cognitive mapping is meant to inhabit the same gap as Althusser’s ideology. The mapping Jameson desires, then, is not an abstract account of the world. It is instead a “representation,” or what he elsewhere calls a “figuration”: some aesthetic that can reveal the world-system in its structural reality through the subjective point of view. Jameson, in other words, is not asking for the novel to lecture us about globalization. He is asking for the novel to represent characters’ experiences of global forces in such a way as to make those forces understandable.

Previously, we searched the immigrant novels closest to this ideal for strategies at the level of content. We found that they all begin prior to immigration, follow multiple characters, and center their narratives around returnees. But we have not yet inquired at the level of form: What formal techniques enable these novels to engage with, and reveal the links between, multiple nations? How, precisely, are they bringing the world into view? On these questions hangs the crucial one. These novels are transnational, and they draw up networks—but what innovations do they offer at the level of representation?

The key features we discover, when we look to formal strategies, turn out to introduce high levels of mediation, freeing the novel in those moments from the bounds of experiential subjectivity—and leaning away from representation and toward didacticism. Americanah introduces the transnational politics mentioned earlier—visas, international charities, refugee crises—by recording long dinner conversations, and comments on how race and class operate transnationally through one character’s pages-long blog posts. No Telephone to Heaven introduces the effects of past colonization on the Jamaican landscape by beginning with a dictionary definition of “ruinate” (Cliff 1); at another point, it quotes a New York Times description of Jamaica (Cliff 200). The “national” immigrant novels discussed earlier use these same techniques to a lesser degree when they do gesture beyond America. For example, White Teeth quotes the Reader’s Digest Encyclopedia’s entry on “Bengali” (Smith 236), the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of “Pandy” (Smith 251)[26] and television news anchors discussing the Berlin Wall (Smith 240), providing what little transnationalism is present. In Native Speaker, a politician’s speech includes commentary on American race relations as well as some history of the Japanese colonization of Korea—one of the only mentions of Korean history in the entire novel (Lee 153). In a number of these novels, like in Americanah, discussions between intellectuals are transcribed as if from a microphone. The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao simply takes this trend one step further, providing sociopolitical context not just in distinct quotations but through actual footnotes—not even attempting to incorporate them into the body of the narrative. Three striking corollaries follow.

First, list the techniques we have just identified—lectures, dictionary definitions, speeches, blog posts, footnotes—and we come to an arresting realization: these novels only seem to map when they are themselves least novelistic. We can ask, then: if what we desire is information on Trujillo’s regime, why not open up a history textbook? If we want to learn about race relations, why not find an actual blog on the subject, rather than a fake blog-within-a-novel? Of course literature can generate associations around mere information in ways that most footnotes and blog posts and dinner conversations do not. At the very least, they are written in character. But can we really claim the pedagogical function as a novelistic achievement if the novel must shrug off its own form to accomplish this?

Second, the achievement of these exemplars is precisely pedagogical, not in fact representational in the sense Jameson was after. These features hardly form the link he recommended between subjective experience and abstract information; they simply insert passages of abstract information into plots otherwise governed by subjective experience, putting the narratives on pause as they do so. In Americanah, for example, some of Adichie’s blog posts are quoted in order to be treated in the narrative, as when a post about a friend—a young woman with “Unknown Sources of Wealth”—angers her, leading the protagonist to take down the post and drive over to her friend’s house to apologize (Adichie 521). But others come at the end of chapters, distinct from the storyline around them.[27]

Third and lastly, this separation not only arises within the stories, but actually manifests on the very pages of these novels. Indentations and white space set apart dictionary definitions and blog posts from the rest of the prose. And if these features put the narratives on pause, then Díaz’s footnotes, as well as Cliff’s glossary (an item much less common in immigrant novels than one might expect; of the twelve novels discussed, only this one can boast a glossary), do so to a different degree entirely, making the disjunction truly disturbing to the reader. In Oscar Wao, there will be a footnote next to a name in a character’s dialogue, and we will have to choose whether to finish the paragraph (in which case we are reading without knowing the referent of that unfamiliar name) or jump immediately to the bottom of the page, in which case we have vaulted out of the conversation (out of the realm of the subjective) and into the realm of the abstract. Similarly, while most immigrant novels ensure that the rough meaning of non-English phrases is discernable from context—and if not, find a way to translate them for us, like having a character ask what a word means so that others will “represent” it[28]—No Telephone to Heaven includes untranslated slang without clear context clues, forcing the reader to suspend the story to flip to the back of the book instead of gleaning the meaning organically.[29]

This is, of course, what our everyday experience is really like. We are inescapably restricted to the “monadic ‘point of view’” (Jameson, “The Cultural Logic” 53). Jameson characterizes postmodernism as “a situation in which we can say that if individual experience is authentic, then it cannot be true; and that if a scientific or cognitive model of the same content is true, then it escapes individual experience” (“Cognitive Mapping” 349). There is, again, a contradiction between experience and reality. And these immigrant novelists are underscoring the fissure rather than attempting to bridge it, separating the two on the page and forcing us to prioritize one over the other. The very form of their novels articulates the crisis of mapping.

And it is in this context that we can make sense of that long montage towards the end of Oscar Wao. Díaz may have given us enough information about American and Dominican societies that the poverty of a Third World country oppressed by a dictator and exploited by the international hegemon should not confound us. Yet when Oscar, and we readers, are confronted with the actual beggars on the streets—with children struggling over our table scraps, with an old woman pleading for a single penny—we find ourselves unable to assimilate these experiential data into our mental schema. In Díaz, the causes of this poverty come as it were pre-explained, and yet the reality remains fragmented and inexplicable, unintegrated into a larger, explanatory whole.

We are now in a position to specify more precisely the project of cognitive mapping: a synthesis of the experience of and explanation for global forces. This, we should note, imposes three criteria for judging a novel in this particular regard (which Jameson himself emphasizes is not intended to displace other aesthetics; after all, art has always had “a great many distinct and incommensurable functions” (“Cognitive Mapping” 347)). First, the content of the novel needs to be transnational; second, the novel must routinely reach for explanation; and third, the novel must incorporate that explanation into the narrative itself, rather than setting it apart as learned discourse. It turns out that immigrant novels, a genre we might expect to be inclined toward such a project, almost never hit these marks. Some, like Danticat’s Breath, Eyes, Memory, do not contain a strong explanatory impulse; they focus almost exclusively on the experience side of the binary, even when that experience seems incomprehensible without context, and even when—like with the men talking politics in the restaurant—such explanation is relegated just offstage. And a great many other immigrant novels are not particularly interested in the globe at all: the majority because they are confined to a single nation; others because, though multinational, they still take the nation as the unit of analysis and do not examine the connections between nations, as in Alvarez’s Garcia Girls; and still others because they reduce one or more nations to their connections with other nations, as in Shteyngart’s The Russian Debutante’s Handbook. The few that do manage to transcend the nation and include both experience and explanation—Americanah, Oscar Wao, No Telephone to Heaven—nevertheless keep the two largely distinct, even to the extent of separating them formally. And the problem with that, as one character in White Teeth insists, is that if you are looking for full stories, “epic” stories,[30] “[y]ou don’t find them in the dictionary” (Smith 252)—not even, we can add, in dictionaries within novels. The result is that characters like Oscar cannot apply their knowledge to their first-order experience, with the suggestion that we readers, too, may not be able to. A work of explanatory realism frets that explanatory realism is not enough.

We find ourselves, then, with three possibilities, three potential verdicts on the project of cognitive mapping. We will take each in turn.

We might conclude, first, that all three stipulations of the cognitive mapping project are desirable and at least potentially feasible. The immigrant novels we have analyzed have, admittedly, not reached this standard. Perhaps we simply need to read more of them, or look back to science fiction, or find another genre entirely—but Heise, Ghosh, and Jameson have articulated a program worth undertaking.

This hinges on whether there is something about representation as such that we should value, something missing when experience and explanation are simply placed side-by-side and not synthesized. Whether the narrator imparts context directly to readers in what we can call “soundtrack information” (such as Balzac’s self-footnoting or Díaz’s footnotes), or alternatively, like a stage play, the novel limits itself to “diegetic information” (such as dinner conversations or TV news, in which the source of the information is present to the characters), the novel has still not achieved representation proper: both techniques simply provide us with passages of abstract, scientific information, sandwiched between involving episodes of story. Yet if Jameson is right that between experience and explanation there is, at best, a gap or a rift, and at worst, a contradiction, then simply providing us with both does not allow us to apply one to the other.

And why should this task of reconciling the two seem pressing? The “aesthetic of cognitive mapping” is ultimately seeking to “endow the individual subject with some new heightened sense of its place in the global system” (Jameson, “The Cultural Logic” 54). This is what multinational capitalism has robbed us of, with the “hyperspace” of advanced modernity having “transcend[ed] the capacities of the individual human body to locate itself, to organize its immediate surroundings perceptually, and to map cognitively its position in a mappable external world” (Jameson, “Postmodernism and Consumer Society” 15-16). Locating oneself, of course, necessarily involves a relation between the monadic point of view and the abstract grid—and didacticism in any form can only give us the grid, not the relation between the two.[31] Mere description, in this view, may be able to teach us about our world but cannot help us locate ourselves within it.

This is Oscar’s dilemma: he has access to his own experience as well as a working model of the external world, and yet he is still no closer to locating his position within it—and so he is unable to organize his immediate surroundings, resulting in that barrage of sensations. Without an understanding of his own positioning, he is also unable to catalyze change: he “give[s] out all his taxi money to beggars” and yet cannot make a dent. We see this too in No Telephone to Heaven, the novel that of them all probably comes closest to a synthesis. After insisting (echoing Mengestu’s protagonist who cannot hold onto both halves of the narrative), that “we will have to make the choice. Cast our lot. Cyaan [Can’t] live split. Not in this world,” Clare’s friend tells her in a long didactic passage about the canefields around them and the history of slavery in the region. “I am sorry to preach,” the friend says. Then comes Clare’s impatient mental response: “And what am I supposed to do about it?” (Cliff 131-33). Clare cannot access both Jamaica and the West at once—she will, as her friend says, be forced to choose—and being told about the impact of the global slave trade on her local surroundings does not help her understand her place in the world.

Of course Oscar and Clare are powerless, goes this argument: a textbook explanation of the world, uninformed by our own experience, is irrelevant to us. The alternative is also true: a detailed account of our experience, uninformed by our place in the world, is not reliably connected to the world around us. What representing the world-system would grant us is a way “to grasp our positioning as individual and collective subjects and regain a capacity to act and struggle which is at present neutralized by our spatial as well as our social confusion” (Jameson, “The Cultural Logic” 54). This is what novels can do that textbooks and encyclopedia entries cannot: help us grasp our positioning in a system so we can recognize the system as the product of our collective agency. And this is what none of these immigrant novels, for all their achievement, fully attain, committed as they are to didacticism.

So what would an immigrant novel that truly represents a multinational slice of our world-system look like? If the crisis under late capitalism is that we cannot experience the truth of our world, then this is what we should ask the novel to do. Characters must not be told the big picture, as diegetic techniques allow, but rather must come to glean the big picture in their everyday lives. We see a glimmer of this in No Telephone to Heaven, with Clare at the end of the novel fixated on understanding her place in the world, and being moved to action because of her rootedness in place. Her friend had told her earlier, “Cyaan [Cannot] live on this island and not understand how it work, how the world work” (Cliff 123). Although she cannot, ultimately, understand how the world works simply from seeing the effects of multinational capitalism in one location, Clare is from then on working to glean an understanding of the world as she moves through it, which is precisely the impulse such a novel would need.

We could choose to hold out for a novel such as this. But that is not the only possibility. We might decide, second, to embrace the first two stipulations of cognitive mapping—global content and setting, and explanatory impulse—but reject the third, concluding that we are mistaken to demand a synthesis of explanation with subjective narration. We can come at this view from two angles. Either (the optimistic view) the synthesis of experience and explanation is unnecessary, even undesirable, which means that some of the immigrant novels we have identified do, more or less, achieve something worth defending; or, alternatively (the pessimistic view), the synthesis is in fact impossible, however desirable we find it. Either way, we will end up rejecting a synthesis as the goal.

Perhaps, in support of the optimistic view, the division of explanation from narrative that we see in these last immigrant novels should not bother us at all. If this is what it takes to transcend the national scale, why not be satisfied? Immigrant novels might be especially drawn to explanation, as they cannot rely on their readers to recall their mandatory two seconds of Dominican (Haitian, Bengali, etc.) history. “To teach, to move, to delight” (Jameson, “Cognitive Mapping” 347)—the novel does all three—why ask it to do all three at once? There are at least three reasons why one might condone, even embrace, this didactic impulse without desiring any synthesis at all.

First, one of our worries had been that if transnationalism only enters at moments when novels adopt other literary modes, this could be a sign that the novel as a genre really is incapable of engaging with global issues. If a novel, so this argument went, has to quote an encyclopedia to bring up Dominican-American political relations, don’t call what it is doing novelistic innovation; it has simply given up its novelness and let an entirely different medium intrude. Yet the tendency of these immigrant novels to provide explanation via embedded media is not contrary, in fact, to traditional novelistic technique. Rather, the form’s willingness to incorporate other genres into its prose is itself a key feature of the novel, and immigrant novels only “heighten the qualities of mixture that theorists of the novel have long described as fundamental to the genre” (Miller 201).[32] Canonical novels routinely feature snippets of poetry, epistolary correspondences, radio broadcasts. Why not blog posts or encyclopedia entries or, finally, footnotes? The inclusion of other genre impulses is, itself, novelistic, and finding new ways to embed media may be enough of an innovation.

Second, reaching for didacticism too has been a common novelistic impulse. Nominally, Lukácsian mapping is supposed to take place via narration, carried by characters. And as it is, the didactic passages in these immigrant novels are more aligned with Lukács’s denigrated “description” than his venerated “narration” (“Narrate or Describe?”). Yet many of his own exemplars do not live up to his standard, comfortable as they are with explanatory passages that fall out of narration. Indeed, canonical social realist novels routinely snub the “show, don’t tell” rule. We might consider James Fenimore Cooper and Lukács’s own beloved Walter Scott, who typically open their books with pages of scene-setting and background before introducing a single character. Or the no-less-Lukácsian Balzac, whose narrator has been known to write that it is “necessary to pause here” to detail the geography of an old city, “without which account it will not be possible to understand” one of the characters (32). This is basically an in-line footnote; Díaz’s actual footnotes simply take what proves to be a wholly common novelistic impulse to its page-formatting conclusion.[33] If we are simply looking for a social realism capable of bringing into view extended social networks, then we are not necessarily looking for Jameson’s integrated representation. We, like Lukács, may simply be looking for authors who make art out of social explanation—a task at which these last immigrant novels excel.

Finally, we may not merely wish to tolerate description, because it has happened to be successful in other novels; we might in fact argue that the novel’s ability to tell rather than show is one of its greatest assets. Fledgling novelists are often told to “think of your book as a movie or a stage play” (Morrill). If an audience couldn’t see it or hear it, it is telling—don’t put it in. But novels are not movies or plays; why limit them as if they were? Why should prose fiction give up the huge advantage it has over visual narrative: namely, that it can deliver context non-scenically?

If we are convinced by these arguments—if readers are perfectly capable of applying the knowledge they glean from “internal footnotes” to the rest of the narrative, so long as they are provided with both—then we need not look any further: these last immigrant novels we have identified have, in fact, with the help of a thinking reader, achieved the desired reconciliation of experience with structural reality. We have been making too much of Oscar’s confusion.

There is, of course, the pessimistic alternative: that the synthesis is desirable, that there is something important these novels are lacking, and yet the task is simply hopeless. In this view, the best these novels can do is provide experience and explanation side-by-side; they are incapable, even with interpretive help, of synthesizing the two. If we take seriously Jameson’s insistence that there is a gap, even a contradiction, between experience and reality, then we might reasonably conclude that readers cannot be expected to apply the didactic information a novel provides to make sense of the narrative. And when it comes to global matters, it may simply be too much to expect novelists to reconcile that contradiction either. The crisis of contemporary narrative in this case remains, and the immigrant novels we have analyzed only showcase this. But they have gotten as close as they can to fostering the global understandings Heise desires.

Whichever of these we choose—that the synthesis is undesirable, or that it is desirable but impossible—we end up with the same verdict: that we should stop creating a novelistic imperative out of cognitive mapping. Whether literature cannot manage it, or literature has already managed it with the readers’ help, or we do not even want it in the first place, there is no reason we should insist on Jameson’s stronger claim that the task of literature is to bridge subjective experience and structural reality. All we might ask is that literature find ways to incorporate both.

So far, our two possible verdicts on cognitive mapping assume that at least the first two stipulations are worthwhile: that we ought to desire spatially expansive content, and that we ought to look for literature that is inclined to teach us about that content. But there is also a third potential verdict that rejects these assumptions.

We might decide, lastly, to reject more than one, even all three, of the stipulations of the cognitive mapping project, and conclude that we are mistaken to even desire global explanation from literature. If even immigrant novels, which we might expect to excel at such a project, turn out not to meet the three stipulations named above, then perhaps the stipulations themselves are misguided and ultimately not useful. This is a conclusion open to us to draw. It would seem to depend on our valuation of the social realist tradition, which has historically placed an emphasis on the pedagogical function of art, but which has also tended to uncritically celebrate unifying projects. Whether social realism can be harnessed to other ends, and whether it can be expanded to a global scale without destroying particularities—as we saw occur in many of these immigrant novels, with every Old Country despecified to serve the same narrative purpose, or with Haiti or Russia becoming just another America—is an essential consideration. Full stories, according to a protagonist in White Teeth, “are like the stories God tells: full of impossibly particular information” (Smith 252). If he is right, then this project might tend uncomfortably toward the imperial gaze. There is the feasibility concern: perhaps novelists cannot possibly play God, in which case supposedly full stories will consistently, upon inspection, turn out to be quite narrow. And there is the normative concern: should novelists be aiming to play God at all?

We end, then, with a recognition that the conclusion we draw from this analysis of immigrant literature depends almost entirely on our theoretical commitments: on what we believe literature is for, and what we want the novel in particular to accomplish. If we believe that novels are best suited for revealing the particularity of experience, or if we prize different sorts of explanations from the kind mapping solicits, then we will derive from this essay a questioning of the standard itself, and will consider Oscar’s mind-bogglement not a puzzle at all, but a reflection of our condition in a globalized world—a condition literature can usefully articulate, but is not meant to solve. If we believe that novels are best suited for description—if their ability to tell, not just show, is their prized feature—then we will be pleased with the last few immigrant novels we explored, and hopeful about the potential of social realism. And if we believe that novels are best suited for integrated representation—and for representing, in particular, a reality that includes a great many global phenomena—then we may be able to take clues from a few of these immigrant novels, but the search, in a variety of genres, will be far from over.

Emma Lezberg is a senior undergraduate majoring in critical theory at Williams College. Her current research examines how figures of scale (local/global, small/big) are deployed in debates around agriculture and food production.

Christian Thorne is a professor of English at Williams College.

Works Cited

Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. Americanah. Anchor Books, a division of Random House LLC, 2014.

Alvarez, Julia. How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents. Alonquin Books, 1991.

Balzac, Honoré de. Lost Illusions. Caxton, 1898.

Barnard, Rita. “Fictions of the Global.” Theories of the Novel Now, Part I, special issue of NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, vol. 42, no. 2, 2009, pp. 207-15.

Bethune, Brian. “Q&A: Author Viet Thanh Nguyen on the ghosts that haunt refugees.”

Maclean’s, 27 Feb. 2017, www.macleans.ca/culture/books/qa-author-viet-thanh-nguyen-on-the-ghosts-that-haunt-refugees. Accessed May 2018.

Boelhower, William Q. “The Immigrant Novel as Genre.” Tension and Form, special issue of MELUS, vol. 8, no. 1, 1981, pp. 3-13.

Boyle, T.C. The Tortilla Curtain. Viking Press, 1995.

“Breath, Eyes, Memory.” Publisher’s Weekly, www.publishersweekly.com/978-1-56947-005-3. Accessed Aug. 2018.

Cliff, Michelle. No Telephone to Heaven. Dutton, 1987.

Daily-Bruckner, Katie. “Reimagining Genre in the Contemporary Immigrant Novel.” The

Poetics of Genre in the Contemporary Novel, edited by Tim Lanzendörfer, Lexington Books, 2016, pp. 219-36.

Danticat, Edwidge. Breath, Eyes, Memory. Vintage Books, 1994.

Díaz, Junot. The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. Riverhead Books, 2007.

Farmer, Paul. “On Suffering and Structural Violence.” Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor, University of California Press, 2003, pp. 29-50.

Ghosh, Amitav. The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable. University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Glesener, Jeanne. “Migration Literature as a New World Literature? An overview of the main arguments.” Aix Marseille University, cielam.univ-amu.fr/node/1983.

Goldberg, Jonah. “Immigrants Are Americans Who Are Born in the Wrong Place.” New York Times, 29 May 2018.

Hallemeier, Katherine. “‘To Be From the Country of the People Who Gave’: National Allegory and the United States of Adichie’s Americanah.” Studies in the Novel, vol. 47, no. 2, 2015, pp. 231-45.

Heise, Ursula K. “Climate Stories: Review of Amitav Ghosh’s ‘The Great Derangement.’” Boundary 2, 19 Feb. 2018.

Heise, Ursula K. Sense of Place and Sense of Planet: The Environmental Imagination of the Global. New York, Oxford University Press, 2008.

Jameson, Fredric. “Cognitive Mapping.” Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, University of Illinois Press, 1988, pp. 347-57.

Jameson, Fredric. “Postmodernism and Consumer Society.” The Cultural Turn: Selected Writing on the Postmodern, 1983-1998. London, Verso, 1998, pp. 1-20.

Jameson, Fredric. “The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism,” Postmodernism, or, The Cultural

Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, Duke University Press, 1991, pp. 1-54.

Jameson, Fredric. The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act. Cornell University Press, 1981.

Kirsch, Adam. The Global Novel: Writing the World in the 21st Century. Columbia Global Reports, 2016.

Lahiri, Jhumpa. The Namesake. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2004.

Lee, Chang-rae. Native Speaker. Riverhead Books, 1995.

Lukács, Georg. “Narrate or Describe?” Writer and Critic: and Other Essays. Edited and

Translated by Arthur Kahn, Grosset & Dunlap, 1971, pp. 110-148.

Lukács, Georg. The Historical Novel. London, Merlin Press, 1962.

Mengestu, Dinaw. The Beautiful Things that Heaven Bears. Riverhead Books, 2007.

Miller, Joshua L. “The Immigrant Novel.” The Oxford History of the Novel in English: The

American Novel 1870-1940, edited by Priscilla Wald and Michael A. Elliott, vol. 6, New York, Oxford University Press, 2014, pp. 200-17.

Morrill, Stephanie. “How to SHOW your story instead of telling it.” Go Teen Writers, 14 Apr. 2014, goteenwriters.blogspot.com/2014/04/how-to-show-your-story-instead-of.html. Accessed Aug. 2018.

“Naturalization Oath of Allegiance to the United States of America.” U.S. Citizenship and

Immigration Services, 25 June 2014, www.uscis.gov/us-citizenship/naturalization-test/naturalization-oath-allegiance-united-states-america. Accessed Aug. 2018.

Roth, Henry. Call It Sleep. New York, Robert O. Ballou, 1934.

Shteyngart, Gary. The Russian Debutante’s Handbook. Riverhead Books, 2003.

Smith, Zadie. White Teeth. New York, Penguin Books, 2001.

“Solutions.” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, www.unhcr.org/solutions.html. Accessed Sept. 2019.

Thorne, Christian. “Grassy-Green Sea.” Early Modern Culture, no. 5, 2006, emc.eserver.org/1-5/thorne.html.

Thorne, Christian. “Providence in the Early Novel, or Accident if You Please.” Modern Language Quarterly, vol. 64, no. 3, 2003, pp. 323-347.

Thorne, Christian. “The Sea is Not a Place; or Putting the World Back into World Literature.” Boundary 2, vol. 40, no. 2, 2013, pp. 53-79.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction. Duke University Press, 2004.

[1] This essay was co-written by Emma Lezberg and Christian Thorne, with Emma Lezberg as lead author. Christian Thorne generated the initial questions. Emma Lezberg did all of the research, generating the essay’s literary judgments and arguments in conversation with Christian Thorne. She also produced two major drafts of the essay, each of which Christian Thorne revised.