This article was published as part of the b2o review‘s “Finance and Fiction” dossier. The dossier includes a response to this article by Dominique Routhier.

“Read Sun Zi”

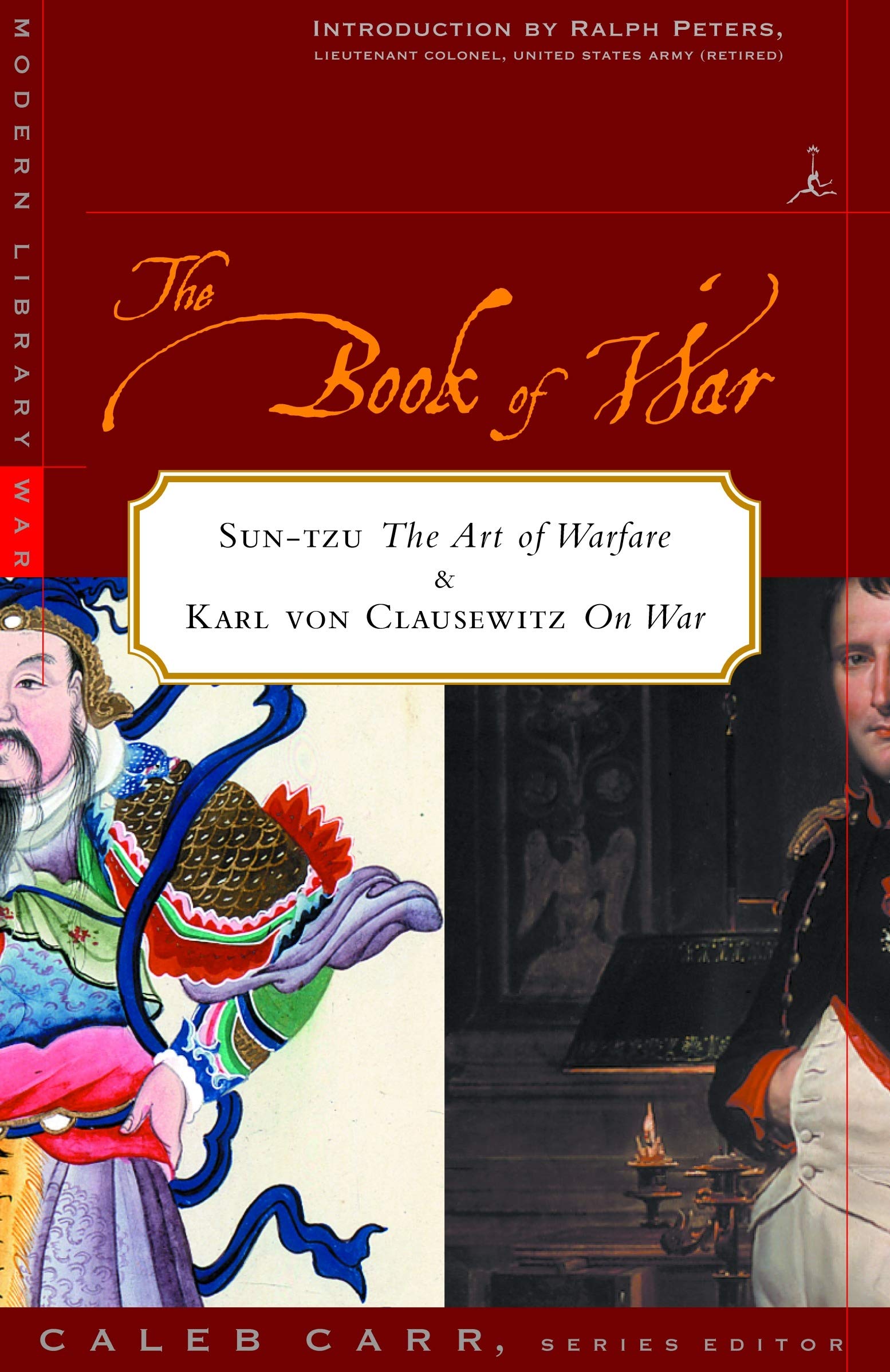

I want to begin with a bit of locker-room talk I came across when I was doing the primary research for my book Finance Fictions (Boever 2018).[1] It’s a scene from Oliver Stone’s film Wall Street (Fox, 1987). The scene shows the by now infamous trader Gordon Gekko (memorably portrayed by Michael Douglas), quoting Sun Zi, the ancient Chinese military general and strategist of war,[2] to explain his trading strategy. “Every battle is won before it’s ever fought”, Gekko tells Buddy Fox (played by Charlie Sheen). “Think about it”. The question I want to ask is simple: why is Gekko, a trader, quoting Sun Zi’s The Art of War? Why is Gekko telling us to place our bets on Sun Zi? Let’s think about it, as Gekko suggests.

I’ve started doing this in a roundabout way, through a reading of the French philosopher—Hellenist and sinologist—François Jullien (see Boever 2020).[3] Jullien is a controversial figure, and you’ll probably gather from what follows why that is so; but his work can also be helpful, I want to show, in understanding the appearance of Sun Zi in Stone’s Wall Street. Ultimately, I will also expand my frame of reference beyond finance and think about Sun Zi’s relation to theories of neoliberal government. In fact, if you’ve read some of the literature on finance and neoliberalism, chances are that you’ve come across references to Sun Zi.

Consider another example from a very different but, I would argue, related context: in To Our Friends, The Invisible Committee references Sun Zi multiple times—including, by the way, the quote “to ‘win the battle before the battle’” (Invisible Committee 2015, 137)—to theorize what earlier in the book they understand to be (silently echoing the work of Michel Foucault) neoliberal governance. When they list a range of adjectives to characterize this type of governance, they use “flexible, plastic, informal” and “Taoist” (68). Why “Taoist”?

And to return to finance, and financial fiction: when in Tash Aw’s finance novel Five Star Billionaire, the Shanghai businesswoman (and former left-wing activist) Yinghui Leong attends an event where she is nominated for the “Businesswoman of the Year awards”, Aw lets us know that “the ceremony was held in the ballroom of a hotel … decorated with huge bouquets of pink flowers and banners bearing quotes from Sunzi’s The Art of War: OPPORTUNITIES MULTIPLY AS THEY ARE SEIZED. A LEADER LEADS BY EXAMPLE, NOT FORCE” (Aw 53). Why Sun Zi at this awards ceremony? That is what I propose to think about.

In Management as in War

So, first: Jullien. In an interview with Richard Piorunski that was published in the journal Ebisu in 1998, Jullien states the following (the translation here is mine as in almost all of the other quotations that I’ll be using): “I’ve accompanied French businesses in China to help them negotiate. There are strategies, ancient, classical Chinese strategies, to which the Chinese will stick” (Piorunski 1998, 173). How did Jullien, a sinologist and philosopher, end up accompanying French businesses in China? As Jullien himself indicates in the interview, his presence in China at the side of French businesses is due to his work on efficacy. This work extends over three volumes. There was, first, the book The Propensity of Things, which (as per its subtitle) proposed to work “Toward a History of Efficacy in China” (Jullien 1995). This was followed by the much shorter A Treatise on Efficacy: Between Western and Chinese Thinking (Jullien 2004), which explicitly continued the thinking of the earlier book. (Both of those titles have been translated into English.) Finally, there is Jullien’s still untranslated Conférence sur l’efficacité [Lecture on Efficacy] (Jullien 2005), which is even shorter and also more informal in tone, closer to the mode of oral delivery. The title of the book’s German translation is more revealing about the origin of this particular work: Vortrag vor Managern über Wirksamkeit und Effizienz in China und im Westen (Jullien 2006)—in other words: Lecture for Managers on Efficacy and Efficiency in China and the West.

What began as a historical, and densely academic project in Propensity of Things about the notion of potentiality in Chinese thinking evidently morphed over time into a much less dense, much less formal lecture for managers about efficacy and efficiency. The book in the middle, Treatise on Efficacy, is about “warfare, power, and speech” (Jullien 2004, ix). But its opening question already anticipates the later Lecture for Managers: “What do we mean”, Jullien asks there, “when we say that something has ‘potential’—not ‘a potential for’ but an absolute potential—for example [he writes] a market with a potential, a developing business with a potential?” (vii) Treatise might be a book about war, but the theory of war it develops is framed as an inquiry into economic potential, into the potential of a business. Clearly, whatever Jullien will have to say in the book about war is presented as applying to business as well. In management as in war, one might say—a parallelism that I’ll want to extend here to “In finance as in war” and also to “In neoliberalism as in war”. But what would be the content of such a parallel construction? Everything depends here on one’s theory and practice of war.

To give some substance to the parallelism “In management as in war”, I am going to look primarily at the relatively unknown (and untranslated) Lecture for Managers. Lecture reads like an informal summary of Treatise, in other words it’s very much a lecture on war. But this is perhaps not its key concern. If it comes to naming the precise connection between military theory and management theory, it is not so much the notion of “war” as that of “strategy” that is most relevant. Indeed, at its most philosophical, the Lecture seeks to open a divergence between Western and Chinese strategies for bringing something about—strategies for efficacy, as the title of both Treatise and Lecture suggest. At this level, the central question of both the Treatise and the Lecture is not essentially related to war at all; rather, it’s because theories of efficacy have been developed mostly in theories of war that Jullien turns to those to lay out his thinking about efficacy.

After some preliminary remarks that lay out his method and address, indirectly, criticisms that have been levelled at his work, Jullien arrives in his Lecture at what he understands to be the Western approach to efficacy, which constructs a model, plan, or ideal form (eidos, to use the Platonic term) to achieve a goal (telos). Once that’s done, the subject acts according to this plan, seeking to achieve the set goal. He argues that the Western thought of war demonstrates this logic, all the way up to Carl von Clausewitz, who appears in both the Lecture and Treatise as a kind of hinge figure. This is because the late 18th-, early 19th-century Prussian general and military theorist both presents us with Western warfare-by-modelization, if you will, and realizes its limits, namely the fact that no war will match the model, plan, or ideal form—the geometry—that has been set for it. Jullien points out that this kind of objection to Plato already starts with Aristotle, who is much more attuned to what escapes the model (Jullien 2005, 17).

Already with Aristotle then, but this becomes particularly visible in Clausewitz, there is a gap that opens up between the theory and the practice of warfare—“[t]o think about warfare is to think about the extent to which it is bound to betray the ideal concept of it” (Jullien 2004, 11)–and it’s this gap that opens up a point of contact with the Chinese theory of warfare. Clausewitz is particularly attuned to the gap between theoretical and practical war, and theorizes what he calls the “friction” (26) between the model and the reality of it. This is the cross that the Western theory of war has to bear. But Jullien uses this realization, which comes from a gap within the Western theory of war, to jump to Chinese theories of war by Sun Zi (and Sun Bin).

Jullien points out, when he begins to discuss these authors, that “today many managers take inspiration from these authors without understanding them well, both in Europe and in Japan. Those are managers ‘à la Sun Zi’” (Jullien 2005, 29). Chinese strategy, Jullien explains, starts from the potential of a situation (30), from the shi of a situation as he discussed it in Propensity. “[I]nstead of imposing our plan upon the world, we could rely on the potential inherent in the situation” (Jullien 2004, 16). What happens in war—the efficacy achieved in war—needs to be understood as the actualization of that potential, as the natural outcome of the situation (Jullien 2005, 32). Most important when going to war is not to make a model, plan, or ideal Form, but to evaluate the situation and its potential (33): a good general will understand the potential of a situation to such an extent that, when they engage in war, the outcome of the war is entirely predetermined—the situation could not allow it develop otherwise (35). As Jullien explains, because the Chinese theory of warfare focuses on evaluating the potential of the situation rather than making a model, there is zero uncertainty about the outcome it anticipates (the outcome is “unswerving, “inevitable”, determined before the battle, etc. [42]). Whereas in the West, war is haunted by the language of chance, necessitating a plea to the gods through sacrifice for example to try to obtain a desirable outcome, Jullien points out that Sun Zi’s Art of War explicitly forbids this, because nothing in warfare should be exterior to the logic of a situation (35). It’s about a certain kind of attunement with reality that enables one to allow reality to follow its path, its course, its dao, but to one’s advantage in war. Chinese warfare is not warfare-by-modelization but warfare-by-regulation, and the dao is what regulates all things. (The model for this is in fact respiration, breathing in and out.)

If the Western model (and in the opposition that’s developed here you can of course see some of what critics like Edward Slingerland deem to be Jullien’s orientalism at work[4]) is telos-oriented and governed by a means-ends logic, Jullien points out that such an architecture cannot be found on the Chinese side (where we have “set-up” and “efficacy” instead), even if that does not mean it is illogical. Rather, efficacy is achieved by allowing the consequences of a situation to come to fruition or maturation. There is no heroism associated with generals, there is no glory in managing a business. It has nothing sensationalist to it: effective victories remain unseen[5] and they ought, in fact, to be easy: indeed, they merely realize to a business’ advantage the logic that already lay contained in nature. A manager does not so much “do” or “act”, they don’t “force”.[6]

To overstate the case somewhat, one might describe this as a theory of “non-action”,[7] as Jullien does in both the Lecture and the Treatise (Jullien 2004, 84-103). (It’s worth pointing out that this term “non-action” translates the key daoist notion of “wu wei” that you find in my title, and to which I’ll return later.) It would be more precise, however, to substitute “non-action” by “action through non-action” or “transformation” in this context: the Chinese general—like the Chinese sage, in fact–does not so much do nothing but seeks to discreetly “transform” their adversary rather than confront them head-on. After all, the Chinese model, as Jullien points out, still “leaves plenty of room for human initiative” (Jullien 1995, 203). Nevertheless, if “action” in Jullien’s summary is “of the moment”, “local”, and “subject-related”, “transformation” is “global”, “durational” and “discreet”—it does not necessarily refer back to a subject.[8] While such transformation is efficacious, it takes place “silently” (58), unnoticed. The strategy of transformation breaks with the Western mythology of “the event” (58-62), which is closely related to Christianity in Jullien’s analysis. It’s the Vietnam war, and specifically the strategy of the Vietnamese, that illustrates this best. To win without battle (an overstatement, surely?): instead, there is “a process of progressive erosion, of making the adversary lose countenance” (61), which Jullien associates with “psychological warfare” (61). In the West, warfare amounts to destruction. But in the Chinese theory of warfare, losses ought to be avoided, and on both sides: in war, it’s preferable to leave the troops intact (62; Jullien 2004, 47). He associates this with deconstruction rather than destruction (Jullien 2004, 48).[9] As Jullien also puts it in Treatise: “nothing could be more economical” (48). And indeed, we should not forget that Jullien is offering all of this theory of Chinese warfare in the context of a Lecture for Managers. Management is a little like psychological warfare, he appears to be saying; you’re trying to de-countenance your adversary not through action but silent transformation. That’s what management is all about.

Path into China

Given the above overview, I suppose it should come as no surprise that research on Jullien will turn up articles written by military officers and business leaders.[10] Of Jullien’s reception in management theory, I’ll discuss just one example, Dominique Poiroux’s “En quête de la voie en Chine” (“In search of the path in/into China”), published in the Journal de l’école de Paris du management. Poiroux is credited simply by the name of the business for whom at the end of 2002, he left to China: “Danone” (Poiroux 2007, 8). The article summarizes his experiences in 8 sections whose titles operate as statements summarizing their main advice. Let me list them to give an idea of their range:

- “Cent jours pour écouter” (“One hundred days for listening”)

- “Prendre du recul” (“Taking a step back”)

- “Gagner du temps” (“Gaining time”)

- “Si l’ennemi ne peut être arrêté, préparer une alliance” (“If the enemy can’t be stopped, prepare an alliance”)

- “Rester humble au quotidien” (“Stay modest in relation to the everyday Chinese person”)

- “Un demi-effort, cent succès; cent efforts, un demi-succès” (the Chinese proverb is included in transcribed Chinese as well: “shi ban gong bei; shi bei gong ban”; “half an effort, one hundred successes; one hundred efforts, half a success”)

- “Se séparer d’un collaborateur, mais rester bons amis” (“Separating oneself from a collaborator, while staying good friends”)

- and finally “Savoir se laisser mener en bateau” (here too, in the transcribed Chinese: “man tian guo hai”; “letting oneself be guided in a boat”).

Rather than explain all of these, I want to note that the first section of Poiroux’s article explicitly credits a lot of these wisdoms to Jullien, with Poiroux writing that Jullien’s book Treatise on Efficacy will often be quoted in the sections that follow. He does not clarify what Jullien’s book is about—war–, only that while he will be applying it to management, “it was not at all written in that context” (Poiroux 2007, 9). It’s worth noting that this is in fact an overstatement: as I’ve discussed, Jullien’s book is explicitly framed through a question about the potential of a business and it includes several references to the economic realm and management strategy. That Jullien’s book is a work of military theory certainly becomes visible in the short section titles that I’ve listed: suddenly, the Danone business leader can use the military language of “enmity” and “alliance” to summarize his management advice. It’s remarkable, I think, that there is no reflection on this shift in the article: it shows to what extent the presence of military language is simply accepted in this context as the language of management. “Strategy” seamlessly crosses here from military into management theory, anecdotes from military history are without any friction applied in the context of management and as part of the broader project of explaining to Western business leaders how to find a “path” in or into China, as the article title puts it. The use of the term “path” by the way is itself significant: it is a rather obvious pun on the Chinese notion of the dao, the path or way that is the flow of all things; but it is repurposed here as part of a Western business strategy for gaining an economic foothold in China.

Many other articles can be found to illustrate the easy exchange between military theory and management theory, which revolves around the term “strategy”. While those never demonstrate any deep engagement with Jullien’s work (often they aren’t even context-specific), the casual references to his thought are many and contribute to the development not only of business strategies in China specifically but—and this is worth emphasizing–of management theory in general. This is different from Poiroux’s use of Jullien in a specifically Chinese situation. China’s non-Western model of warfare as it is exposed in Jullien’s Treatise becomes highly productive both within Jullien’s work (where it leads to his Lecture) but also outside of it, in its reception in management studies, as part of the development of contemporary management strategies not just for China but at large.

Wu Wei and Laissez-Faire

This is where I want to expand the frame of reference beyond management to theories of neoliberal government. For there are elements in the Chinese theory of war that resonate with what one might call today’s neoliberal government. I can argue this theoretically, but I want to do so historically as well in order to give some factual, non-speculative grounding to this proposition.

Consider for example the chapter “Do Nothing (With Nothing Left Undone)” in Jullien’s Treatise, where Jullien as elsewhere in his work suggests that one of the models for efficacy (both in war and elsewhere) is “the growth of plants” (you will find this model discussed in the work of the later Confucian Mong Zi or Mencius, by the way) (Jullien 2004, 90). This is because

one must neither pull on plants to hasten their growth (an image of direct action), nor must one fail to hoe the earth around them so as to encourage their growth (by creating favorable conditions for it). You cannot force a plant to grow, but neither should you neglect it. What you should do is liberate it from whatever might impede its development. You must allow it to grow. Such tactics are equally effective at the level of politics. A good prince … is a ruler who, by eliminating constraints and exclusions, makes it possible for all that exists to develop as suits it. His acting-without-action amounts to a kind of laisser-faire [my emphasis, ADB] but not to a policy of doing nothing at all. (91)

The idea is repeated in explicitly political terms later on, in the chapter “Allow Effects to Come About”. With respect to political reality, Jullien writes:

The excessive fullness that burdens it is, as we have seen, that of regulations and prohibitions that, as they multiply, end up weighing society down so that it is impossible for it to evolve as it should. An emptiness needs to be created, those regulations must be evacuated, to allow reality the space in which it can take off. For as soon as nothing is codified any more (codification being nothing but a reification of fullness), because nothing any longer bars the way to initiative, this can deploy itself sponte sua. In the emptiness created by the removal of prohibitions and regulations, all that is necessary is to allow things to happen, to allow them to pass through, so that action now occurs without activity. (112)

Even if both of these quotes seem to include an idea of freedom (with the verb “liberate” being used explicitly in the first), one should not get the wrong idea here: it is by allowing the plant to grow, and to develop sponte sua, that the Chinese politician exercises control. So you get a strange situation where the notion of action through non-action, or wu wei, becomes a model for the control exercised by a laisser-faire government. This is the particular exercise of sovereign power that the ancient Chinese sages recommend.

With respect to this phrase laisser faire/ laissez-faire, I have to include here a brief historical note about its origins.[11] I do so specifically because of laissez-faire’s importance in contemporary analyses of neoliberalism. It is worth noting that the phrase laissez-faire originates in the 18th-century French economist François Quesnay’s writings on Chinese despotism. Indeed, “laissez faire” is a French translation of the Chinese notion of “wu wei”, which means—as I’ve already discussed–“without exertion” and is closely associated with the Chinese understanding of effective government. Certainly when the phrase laisser faire appears in Jullien, in a chapter titled “Do Nothing (With Nothing Left Undone)”, that is where we should situate its origins. But as such, the notion’s appearance in Jullien can of course not be disentangled from its translation into the work of Quesnay, and by extension the work of the French physiocrats, whose ideas about the “natural”, “spontaneously” self-regulating market producing the natural “true price” of a good, so interested Michel Foucault in both Security, Territory, Population [1977-1978] (Foucault 2007) (which dedicates a lecture to the physiocrats [Foucault 2007, 55-86]) as well as The Birth of Biopolitics [1978-1979] (Foucault 2008) (which recalls Foucault’s earlier discussion of the physiocrats [Foucault 2008, 30-37]). (As far as I know, Foucault does not mention the phrase’s origins in wu wei; Roland Barthes’ course on The Neutral, however, from 1977-1978 (Barthes 2005) [in other words, at the same as the lectures by Foucault just mentioned] does include a [superficial—as far as I can tell, Barthes relies on a single, secondary source] engagement with Daoism and a discussion of wu wei.) It is this idea of wu wei or laisser faire/ laissez-faire that according to many would later on lead to Adam Smith’s notion of the invisible hand (liberalism/ neoliberalism); at the same time, one might find it present in Jeremy Bentham’s notion of the panopticon as well (sovereignty). These are by no means the only political interpretations that have been given of wu wei: it’s most commonly been associated with political anarchism.

There are at least two things we learn from this genealogy. First of all, wu wei/ laisser faire—and by extension neoliberalism–is a practice of power. Second, it does not mean doing nothing: whatever you understand by “let it be” needs to add up to a practice of acting otherwise, of acting through not-acting (enlarging what’s already happening in nature rather than forcefully going against it). Putting one and two together, we can say that wu wei/ laisser faire names a practice of power that self-occludes. This explains the references to Sun Zi and to Daoism in The Invisible Committee’s To Our Friends, when a theory of neoliberal government is laid out.

At this point we are also in a position to understand why Lao Zi, whose Dao De Jing is in spite of its mere few thousand words the foundational text of Daoism, can be appreciatively quoted in Ronald Reagan’s “State of the Union” address from 1988. The line Reagan quotes about 5 minutes into the address is: “Govern a great nation like you would cook a small fish; do not overdo it”. One year before, Gekko had already quoted Sun Zi, and specifically the idea of wu wei in Sun Zi, in Stone’s Wall Street. Applying wu wei to trading, Gekko appears to place himself precisely within the understanding of neoliberal laissez-faire that I am uncovering here. “I don’t throw darts at a board. I bet on sure things. Read Sun Zi, The Art of War: ‘Every battle is won before it’s ever fought’. Think about it”. If “probability theory” in Jullien’s view is one of the ways in which the West dealt with the tension, central to Clausewitz’ thought, between absolute and real war (Jullien 2004, 42)—and there is a great book on this by the Danish scholar Anders Engberg-Pedersen (Engberg-Pederson 2015)–, Chinese strategy by contrast “has always avoided” “the kind of gamble accompanied by risk and danger” (Jullien 2004, 82).

In today’s situation of neoliberal government, in which the overlap of finance and politics has only intensified, references to Sun Zi have also abounded, and much remains to be explored. In the Introduction to her recent new translation of The Art of War, Michael Nylan points out that “[e]ven before becoming president, Donald Trump tweeted Sunzi wisdom to his followers” (Nylan 2020, 18). Nylan continues:

Trump, unlikely to have read The Art of War, included enthusiasts in his administration. Steve Bannon was a missionary for Sunzi. Sebastian Gorka, former deputy assistant to the president, sported a vanity license plate: “Art War”. (18)

Nylan also quotes James Mattis’ comment that while “the Army was always big on Clausewitz … the Marine Corps has always been more Eastern-oriented” (18). Semper Sun Zi.

Is Wu Wei Neoliberal?

There is a whole other discussion that I’m not completely ready to engage with about whether wu wei is indeed neoliberal—about whether wu wei’s translation into laissez faire and laissez faire’s translation into neoliberalism does indeed hold water. The issue is, perhaps unsurprisingly in the case of a translation like this across time and space, complicated. Although wu wei is typically considered to be a daoist notion (you’ll find both verbal and nominal wu-forms throughout the daoist corpus), it also explicitly appears once in Confucius’ Analects, which in fact mobilizes the notion of wu wei to capture a model of government where the people are not so much guided through “coercive regulations” and “punishments” but by “virtue” (Confucius 2003, 175)—by the ruler projecting virtuous behavior that would then trickle down to their subjects (what one might call today “trickle-down morality”). “Ritual”, not law, is in Confucius’ book, what keeps the people in line. At first sight, this emphasis on virtue may not sound very neoliberal, but that could only be a provisional conclusion: scholars like Melinda Cooper and Wendy Brown have shown, in their books Family Values and In the Ruins of Neoliberalism, how crucial conservative morality is to neoliberal government (Cooper 2017; Brown 2019). Today, of course, this insistence on morality has become hollowed out: Brown writes of a merely “contractual use” of morality by today’s neoliberalism, and this is certainly one of the meanings her book’s title (that we are living in the ruins of the neoliberalism).

Interestingly, the Confucians were precisely accused of such a hollowing out of morality—of morality becoming pure form, devoid of content—by the daoists, who ridiculed what they understood to be the performance of empty ritual. They have been associated, rather, with political anarchism (Ames and Hall 2003, 14; 102), an association that I think moves too far in the other direction since it does not capture the ways in which wu wei’s action through non-action is actually a hierarchical practice of power. (On this count, however, we would need a more extensive discussion of anarchism and its meanings. But it seems this is the obvious reason why The Invisible Committee uses “Taoist” as an adjective to characterize neoliberal government, and not their own anarchist practice.)

The later Confucian Mong Zi or Mencius famously opens his book with a rejection of those who put profit over righteousness: “Why must your majesty speak of profit [he asks King Hui of Liang]? Let there simply be benevolence and righteousness” (Mengzi 2008, 1). Importantly, however, this is not a rejection of those who seek profit as such—only of those who place that pursuit over being benevolent and righteous. Mong Zi’s English translator, the eminent sinologist Bryan Van Norden, summarizes Mong Zi’s position as follows:

Mencius taught that those who are talented have an obligation to use their skills for the betterment of society and not merely their own self-aggrandizement. He said that we must look without ourselves to find our best inclinations and develop them. He argued that loving families with good values produce caring adults who have integrity. He asserted that government must aim at the well-being of all the people not just the well-off. He declared that rulers who punish those who steal because they live in poverty and lack education are merely setting traps for the people. He claimed that war is a final resort that usually causes more troubles than it solves. (Mengzi 2008, 197)

As I’ve already said, the emphasis on “loving families” and “good values” does not necessarily take us out of neoliberalism. But perhaps the focus on “the betterment of society” and the positioning against “self-aggrandizement” do; perhaps the focus on “integrity” (the position against “corruption”) does, too. Most striking here I find the proposition that government must aim at the well-being of all, not just the well-off, and should not punish those who steal because they are poor or uneducated: instead, the implication goes, the government should make sure everyone is educated and lives a good life.

It seems then, that wu wei is not quite comfortably at home on Wall Street, even if (as I’ve shown) it contains quite a few elements that have enabled many to situate it there.

Arne De Boever teaches American Studies in the School of Critical Studies at the California Institute of the Arts (USA), where for over a decade he also directed the MA Aesthetics and Politics program. He is the author of numerous articles, reviews, and translations, as well as several books on contemporary comparative fiction and political and aesthetic philosophy. His most recent books are Against Aesthetic Exceptionalism (University of Minnesota Press, 2019), François Jullien’s Unexceptional Thought: A Critical Introduction (Rowman & Littlefield, 2020), and Being Vulnerable: Contemporary Political Thought (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2023).

References

Ames, Roger and David Hall, eds. Dao De Jing: “Making This Life Significant” (A Philosophical Translation). Trans. Roger Ames and David Hall. New York: Ballantine Books, 2003.

Aw, Tash. Five Star Billionaire. New York: Spiegel and Grau, 2014.

Barthes, Roland. The Neutral: Lecture Course at the Collège de France, 1977-1978. Trans. Rosalind Krauss and Denis Hollier. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

Boever, Arne De. Finance Fictions: Realism and Psychosis in a Time of Economic Crisis. New York: Fordham University Press, 2018.

—. François Jullien’s Unexceptional Thought: A Critical Introduction. New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2020.

Brown, Wendy. In the Ruins of Neoliberalism: The Rise of Antidemocratic Politics in the West. New York: Columbia University Press, 2019.

Confucius. Analects. Trans. Edward Slingerland. Indianapolis: Hackett, 2003.

Cooper, Melinda. Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism. New York: Zone Books, 2017.

Engberg-Pederson, Anders. Empire of Chance: The Napoleonic Wars and the Disorder of Things. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Foucault, Michel. Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-1978. Trans. Graham Burchell. New York: Picador, 2007.

—. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978-1979. Trans. Graham Burchell. New York: Picador, 2008.

The Invisible Committee. To Our Friends. Trans. Robert Hurley. Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2015.

Jullien, François. The Propensity of Things: Toward a History of Efficacy in China. Trans. Janet Lloyd. New York: Zone Books, 1995.

—. A Treatise on Efficacy: Between Western and Chinese Thinking. Trans. Janet Lloyd. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2004.

—. Conférence sur l’efficacité. Paris: PUF, 2005.

—. Vortrag vor Managern über Wirksamkeit und Effizienz in China und im Westen. Trans. Ronald Vouillé. Leipzig: Merve, 2006.

Mengzi. Mengzi. With Selections From Traditional Commentaries. Trans. Bryan W. Van Norden. Indianapolis: Hackett, 2008.

Nylan, Michael. “Introduction”. In: Sun Tzu, The Art of War. Trans. Michael Nylan. New York: Norton, 2020. 9-34.

Piorunski, Richard. “Le détour d’un grec par la Chine. Entretien avec François Jullien.” Ebisu 18 (1998): 147-185.

Poiroux, Dominique. “En quête de la voie en Chine”. Journal de l’école de Paris du management 2: 64 (2007): 8-15.

[1] This text was first presented at a boundary 2 conference at the University of Pittsburgh in Fall 2019 (thank you Paul Bové for the invitation). I later presented revised versions of it at the “Finance and Fictions” event at the California Institute of the Arts in January 2020, and at Syddansk Universitet in Fall 2022 (thank you Anders Engberg-Pederson for the invitation). I would like to express my gratitude to the audiences at those various occasions—which included, in Denmark, my respondent in this forum, Dominique Routhier–for their comments and questions.

[2] The authorship of The Art of War is uncertain as in the case of many ancient texts.

[3] See: Boever 2020. Most of this text is based on what was later published as chapter three of this book, titled “In Management as in War”.

[4] I have commented on this at length in: Boever 2020, Chapter 1.

[5] Ibid., 42.

[6] Ibid., 45.

[7] Ibid., 53.

[8] Jullien, Conférence, 56.

[9] Ibid., 48.

[10] I don’t have time to discuss to military uses of his thought here (on this, see: Boever 2020), but based on articles that I’ve found I conclude that his Treatise is frequently assigned as reading at military academies.

[11] I want to thank Andrew Culp for initially guiding me in this direction.