**PLEASE NOTE THE LOCATION CHANGE FOR SATURDAY DUE TO THE HUGHES FIRE**

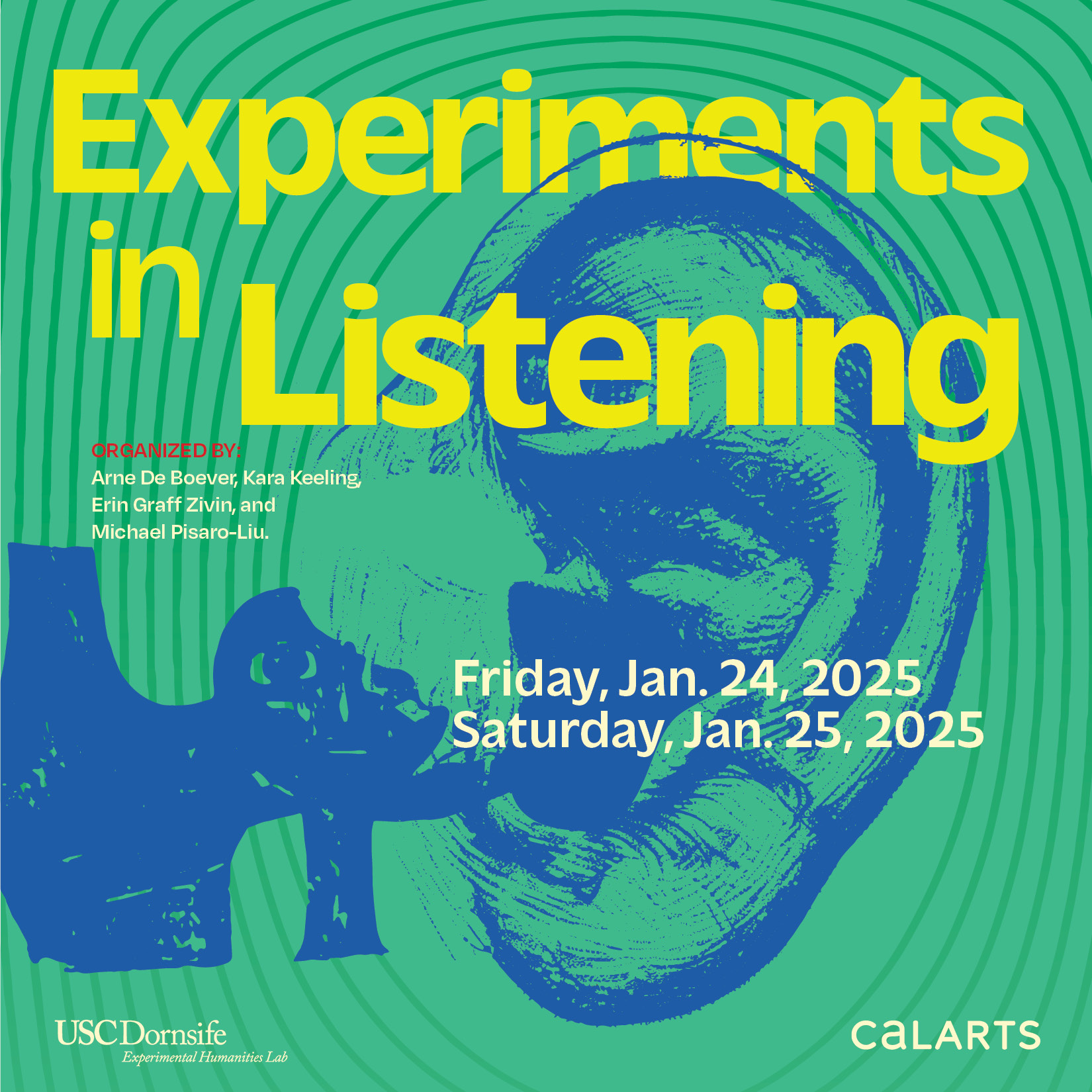

Experiments in Listening

Friday, January 24-Saturday January 25, 2025

University of Southern California and California Institute of the Arts

Supported by the MA Aesthetics and Politics program and the Herb Alpert School of Music at the California Institute of the Arts; the USC Dornsife Experimental Humanities Lab; the Division of Cinema and Media Studies at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts; and boundary 2: an international journal of literature and culture.

With additional support from the Dean of the School of Critical Studies at CalArts; the USC Dornsife Graduate Dean and Divisional Vice Dean for the Humanities, the USC Department of Comparative Literature, and the USC Department of English.

This event is also supported by the Nick England Intercultural Arts Project Grant at CalArts.

Organized by Arne De Boever, Kara Keeling, Erin Graff Zivin, and Michael Pisaro-Liu.

“To anyone in the habit of thinking with their ears…” Thus begins Theodor W. Adorno’s famous essay “Cultural Criticism and Society”. But what does it mean to think with one’s ears? How does one get into the habit of it? And what are the critical and societal (ethical and political) benefits of thinking with one’s ears?

“Experiments in Listening” proposes to address these questions starting from the experimental performing arts. Conceived between an arts institute, a university, and a contrarian international journal of literature and culture, the conference seeks to “emancipate the listener” (to riff on Jacques Rancière) into considering their ears as not only aesthetic but also political instruments that are as central to how we think, make, and live as our speech.

Friday, January 24

University of Southern California

10am-12n

ROOM: USC, Taper Hall of Humanities (THH) 309K

boundary 2 editorial meeting for boundary 2 editors

Lunch for boundary 2 editors and conference speakers

*

1:30pm-3:15pm

ROOM: USC, SCA 112

Listening session/ Moderator: Erin Graff Zivin

Gabrielle Civil, “listening: in and out of place”

Fumi Okiji, “To Listen Ornamentally”

Josh Kun, “Migrant Listening”

3:30-5:30pm

ROOM: USC, SCA 112

Listening session/ Moderator: Kara Keeling

Michael Ned Holte, “Looking for Air in the Waves”

Mlondi Zondi, “Sound and Suffering”

Leah Feldman, “Azbuka Strikes Back”

Nina Eidsheim, “Pussy Listening”

6pm-7:30pm

Dinner for conference speakers — USC

8:00-10pm

ROOM: CalArts DTLA building. 1264 West 1st Street.

8pm: Reception

8:30pm: Screening of Omar Chowdhury, BAN♡ITS (17m22s, 2024) (in progress).

Out near the porous, lawless eastern border between Bangladesh and India, a diasporic artist returns to make works with a band of washed up ban♡its who are obsessed with Heath Ledger’s Joker. As they comically re-enact their glorified past, we confront the divergent histories and philosophies of peasant banditry and political resistance and its unexpected causes and contexts. The resulting para-fiction questions its authorship and morality and asks: when the art world comes calling, who are the real ban♡its?

9pm: Performance by Notnef Greco (Deviant Fond and Count G).

Saturday, January 25

The REEF building (1933 South Broadway, Los Angeles, California 90007)

10-11:50am:

ROOM: Screening Room, 12th floor

Coffee and pastries.

Listening session/ Performance. Moderator: Arne De Boever

Arne De Boever, “Silent Music”

Michael Pisaro-Liu, “Experimental Music Workshop” (1 hour). Performance of Antoine Beuger, Für kurze Zeit geboren: für Spieler/ Hörer (beliebig viele)/ Born for a Short Time: For Performers/ Listeners (as many as you like) (1991).

Conference speakers will participate in the performance. Performance will be audio/video-recorded and posted at boundary 2 online. A livestream will be available here. Composer Antoine Beuger will be joining us for the Q&A after the performance via zoom.

Lunch for conference speakers–Commons, 12th floor

1:30pm-3:15pm

ROOM: Screening Room, 12th floor

Coffee and pastries.

Listening session/ Moderator: Kara Keeling

Gavin Steingo, “Whale Song Recordings”

Natalie Belisle, “Inclination: The Kinaesthesis of Afro-Latin American Sound”

Stathis Gourgouris, “The Julius Eastman – Arthur Russell Encounter”

3:30-5:15pm

ROOM: Screening Room, 12th floor

Listening session/ Moderator: Erin Graff Zivin

Edwin Hill, “On Acoustic Jurisprudence”

Bruce Robbins, “Listening On Campus”

Jonathan Leal, “If Anzaldúa Were a DJ, What Would She Spin?”

5:30-6:15pm

ROOM: Screening Room, 12th floor

Student Theory Slam/ Moderator: Arne De Boever

Reina Akkoush

Jacob Blumberg

Sean Seu

Inger Flem Soto

…

6:30pm-8pm

Dinner for conference speakers–Commons, 12th floor

8pm

ROOM: Screening Room, 12th floor

8pm: Reception

8:30pm: Tung-Hui Hu, “How to Loop Today”

Listener Biographies

Reina Akkoush is an award-winning Lebanese graphic and type designer currently pursuing an MA in Aesthetics and Politics at the California Institute of the Arts. Research interests include Middle Eastern design, Arabic typography, Marxist critical theory, cultural memory and decolonial thought in the global south.

Natalie L. Belisle is an Assistant Professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature in the Department of Latin American and Iberian Cultures at the University of Southern California, where her research and teaching focus on contemporary Caribbean and Afro-Latin American literature, cultural production, and aesthetics. Professor Belisle’s first book Caribbean Inhospitality: The Poetics of Strangers at Home will be published by Rutgers University Press in 2025.

Jacob Blumberg is an artist and producer working across the disciplines of music, film, photography, fine art, performance art, and religious art. Global in scope and local in focus, Jacob’s work as a collaborator and creator centers deep listening, voice, and play.

Arne De Boever teaches American Studies in the School of Critical Studies at the California Institute of the Arts. He is the author of seven books on contemporary fiction and philosophy, as well as numerous articles, reviews, and translations. His new book Post-Exceptionalism: Art After Political Theology was published by Edinburgh University Press in 2025.

Omar R. Chowdhury is a Bangladeshi artist and filmmaker. He creates para-fictional installations, films and performances that animate the fault lines of diasporic life and its various radical histories. He has had recent presentations and performances at Busan Biennial 2024 (South Korea), Contour Biennial 10 (Mechelen), Dhaka Art Summit, Beursschouwburg (Brussels), De Appel (Amsterdam), and screenings at International Film Festival Rotterdam, Film and Video Umbrella (London), Haus der Kulturen der Welt (Berlin), and Queensland Gallery of Modern Art (Brisbane) for Asia Pacific Triennial 8.

Gabrielle Civil is a black feminist performance artist, poet, and writer, originally from Detroit, MI. Her most recent performance memoir In & Out of Place (2024), encompasses her time living and making art in Mexico. The aim of her work is to open up space.

Nina Eidsheim is a vocalist, sound studies scholar and theorist. She brings extensive knowledge, experience and innovative approaches to practice-based research that focuses on sound and listening. The author of Sensing Sound: Singing and Listening as Vibrational Practice and The Race of Sound: Listening, Timbre, and Vocality in African American Music.

Inger Flem Soto is a doctoral student in Comparative Studies in Literature and Culture at USC. She is interested in issues of sexual difference, continental philosophy, psychoanalysis, and Latin American feminist thought. Her dissertation focuses on the mother figure in Chilean works of literature and philosophy.

Stathis Gourgouris is professor of classics, English, and comparative literature and society at Columbia University. He is the author of several books on political philosophy, aesthetics, and poetics, the most recent being Nothing Sacred (2024).

Edwin Hill is Associate Professor in the Department of French and the Department of American Studies & Ethnicity at the University of Southern California. His research lies at the African diasporic intersections of French and Francophone studies, sound and popular music studies, theories of race.

Michael Ned Holte is a writer, curator, and educator living in Los Angeles. Since 2009, he has been a member of the faculty of the Program in Art at CalArts, and he currently serves as an Associate Dean of the School of Art. He is the author of Good Listener: Meditations on Music and Pauline Oliveros (Sming Sming Books, 2024).

Tung-Hui Hu is a poet and media scholar. He is the author of three books of poetry, most recently Greenhouses, Lighthouses, which grew out of his graduate studies in film, as well as two studies of digital culture, A Prehistory of the Cloud and Digital Lethargy: Dispatches from an Age of Disconnection, an exploration of burnout, isolation, and disempowerment in the digital underclass.

Kara Keeling is Professor and Chair of Cinema and Media Studies in the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California. Keeling is author of Queer Times, Black Futures (New York University Press, 2019) and The Witch’s Flight: The Cinematic, the Black Femme, and the Image of Common Sense (Duke University Press, 2007).

Josh Kun is a cultural historian, author, curator, and MacArthur Fellow. He is Professor and Chair in Cross-Cultural Communication in the USC Annenberg School and is the inaugural USC Vice Provost for the Arts.

Jonathan Leal (he/him) is an Assistant Professor of English at the University of Southern California. He is the author of Dreams in Double Time (Duke University Press, 2023), which received an Honorable Mention for Best Book of History, Criticism, and Culture from the Jazz Journalists Association. His next book, Wild Tongue: A Borderlands Mixtape, is under contract with Duke University Press.

Fumi Okiji is Associate Professor of Rhetoric at the University of California, Berkeley. She arrived at the academy by way of the London jazz scene and draws on sound practices to inform her writing.

Michael Pisaro-Liu is a guitarist and composer. Recordings of his music can be found on Edition Wandelweiser, erstwhile records, elsewhere music, Potlatch, another timbre, ftarri, winds measure and other labels. Pisaro-Liu is the Director of Composition and Experimental Music at CalArts.

Bruce Robbins is Old Dominion Foundation Professor in the Humanities at Columbia University. He is the author of Secular Vocations: Intellectuals, Professionalism, Culture (1993), Perpetual War: Cosmopolitanism from the Viewpoint of Violence (2012), and, most recently, Atrocity: A Literary History (2025).

Gavin Steingo is a professor in the Department of Music at Princeton University. He is working on a series of books and articles about whales, music, politics, and the environment.

Sean Koa Seu practices dramaturgy, theater direction, and production. He has credits with the National Asian American Theatre Company, Transport Group, and Lincoln Center Theater. He produced the short documentary The Victorias, which was acquired by The New Yorker in 2022.

Erin Graff Zivin is Professor of Spanish and Portuguese and Comparative Literature at the University of Southern California, where she is Director of the USC Dornsife Experimental Humanities Lab. She is the author of three books—Anarchaeologies: Reading as Misreading (Fordham UP, 2020), Figurative Inquisitions: Conversion, Torture, and Truth in the Luso-Hispanic Atlantic (Northwestern UP, 2014), and The Wandering Signifier: Rhetoric of Jewishness in the Latin American Imaginary (Duke UP, 2008)—and is completing a fourth book entitled “Transmedial Exposure.”

Mlondi Zondi (they/he) is an assistant professor of comparative literature at the University of Southern California. In addition to scholarly research, he/they also work in performance and dramaturgy. Mlondi’s writing is forthcoming or has been published in TDR: The Drama Review, ASAP Journal, Liquid Blackness, Contemporary Literature, Text and Performance Quarterly, Mortality, Canadian Journal of African Studies, Safundi, Performance Philosophy, Espace Art Actuel, and Propter Nos.