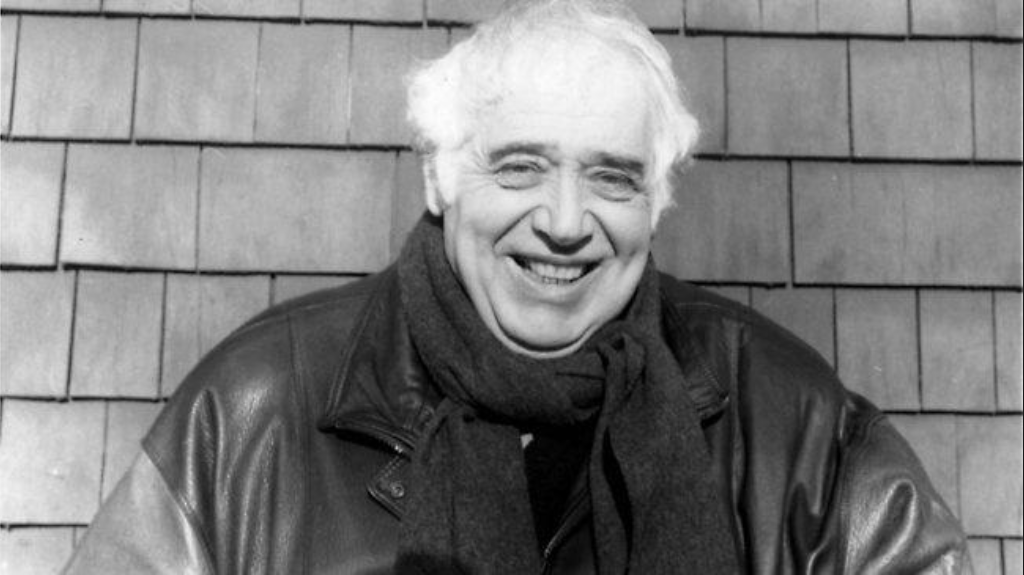

by Lionel Ruffel

Translated from the French by Claire Finch and Jackson B. Smith

We are watching a man on a screen. He displays all the characteristics of a vigorous, conservative, republican, married, paternal, naturally born-to-lead American. He’s white, his name is Glenn Beck, he has a baby face and a crew cut, and he’s wearing the mandatory uniform — a red tie with white stars, a striped shirt, and a dark suit. He leans his elbows on the table, using them to emphasize all of his gestures. It’s like we’re at his house and he’s talking to us in private. He’s speaking to us so casually that it even feels a little like water cooler gossip, but don’t let that fool you: what he’s about to tell us is serious. We’re watching Fox News; it’s July 1st, 2009. He starts with the typical idiotic conspiracy theories. But then, less than a minute into the show, something happens, and suddenly we’re confronted with the unexpected, the incredible, the weird: he holds up a small book, yes, you heard me correctly, a book. And he not only holds it up, he flips through it, turning a few pages without reading them, and we can tell right away that he hasn’t read the book and that this doesn’t matter. He hasn’t read it yet, because he just got it, but he’s been waiting for it for a long time. “It is a brand new book,” he tells us, and he looks at us, knowingly, “it is a dangerous book,” and he looks at us threateningly, “it is called The Coming Insurrection,” and here he takes his time, exaggerating each syllable. He holds up the book again, making sure to repeat the title two times, and the second is even more terrifying than the first. “It is written by the Invisible Committee.” Now he looks utterly aghast, because, as he’s speaking, at this very moment, “it calls for a violent revolution.” He gives a little automatic smile, a knowing smile, when he tells his viewers that this Invisible Committee is an anonymous group—and he emphasizes anonymous—and they come from France, of course, although he doesn’t actually say “of course,” we can hear it anyway.

*

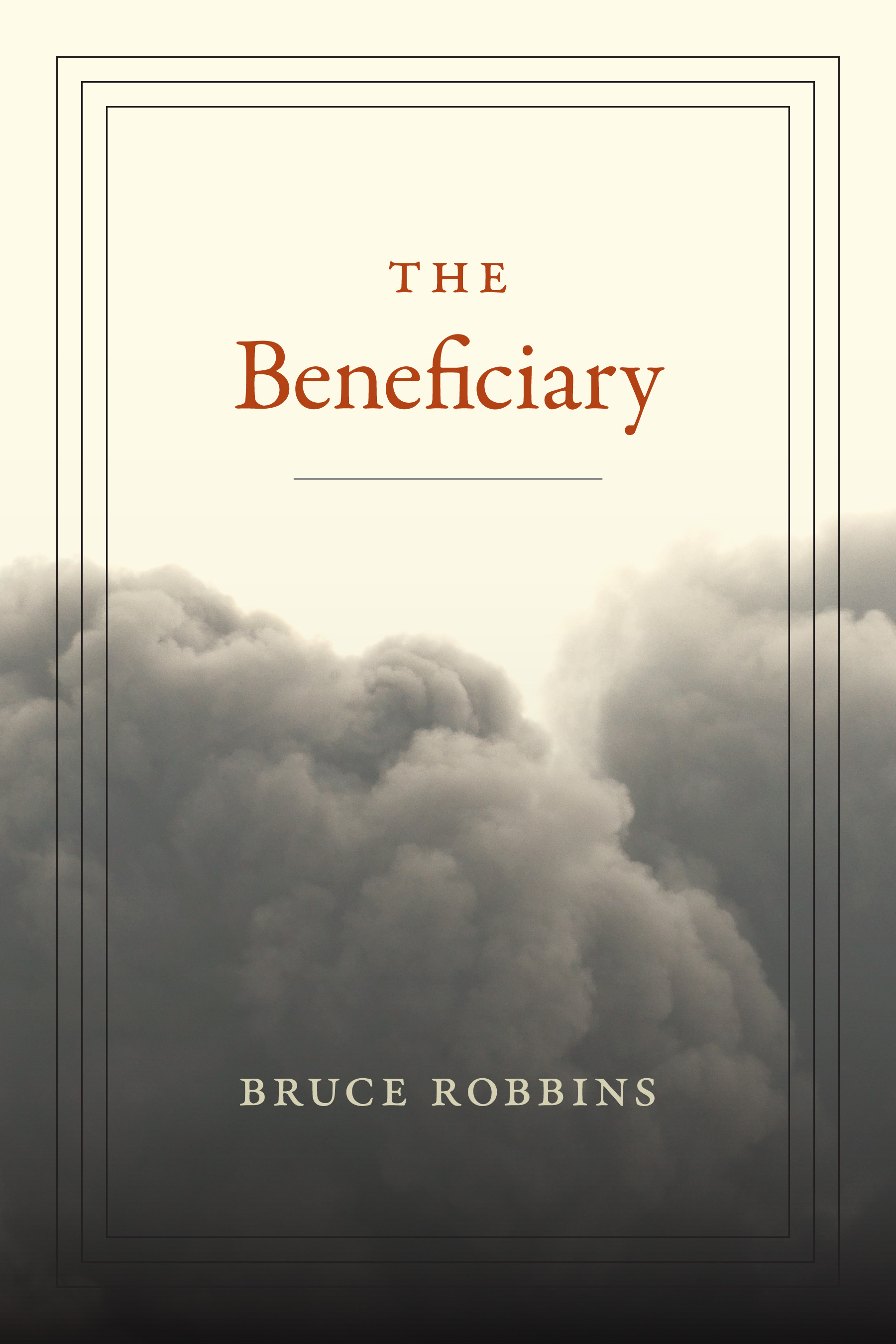

What makes a book dangerous? So dangerous that a celebrity commentator of a major conservative American television network would devote so much energy to it. So dangerous that the French state imprisoned nine people and flung open what became known as the so-called “Tarnac” case, getting wrapped up in another one of those judiciary true-crime fiascos that it does so well. The combination of the two, the celebrity commentator and the French state, thus gave the book a double recognition the likes of which no French book has received in a very long time. We can’t help but think about similar cases that came before, even though they already seem like they happened so long ago: Guyotat, Genet; or the cases that happened even longer ago: Baudelaire, Flaubert. I recall those cases of literary trials, because the so-called “Tarnac” case, and here comes my hypothesis, is fundamentally a literary trial, even though we’re using it as a false pretext to debate terrorism in our courts. Each of these literary trials thus reveals an anxiety that corresponds to its period, an anxiety about the production of literature and the production of truth. When we talk about the 19th century, we often mistakenly bring up morality, but it was actually all about putting realism on trial. When we talk about the 1960s, we discuss morality and politics, but the true source of anxiety was the hordes of young educated people and readers, let’s call it “democratization.” With the Tarnac case, we talk about terrorism, but it’s a trial that pulls us back to the question that Kant famously asked in 1790: “What is a book?” And it’s true, after all: What is a book? What is a book that Glenn Beck waves at us on a television set? What is a book when we’re reading its unauthorized translations in the middle of a coffee shop? What is a book that leads to the arrest of nine people? These questions are not at all insignificant, because their answer depends on how we think about the collective body, about politics, and about democracy.

I might be moving too fast, and if you aren’t already familiar with the case, I can quickly go over its main cadences. The starting point was nothing out of the ordinary: a book, called The Coming Insurrection, and some criminal intrigue: someone sabotaged several train lines. The two are linked by a series of readers: the police, the legal system, and the political world, which I’ll call “bovaryan” because…ok, let’s put it in the most simplistic terms, they have a tendency to confuse what is real with what is fiction. The book in question, The Coming Insurrection, the one that worried Glenn Beck so much before he even read it, thus became the sole evidence in a trial by media, and an important one, as its principal actors were the then-Minister of the Interior and the still-acting head of the SNCF (the French National Railway Corporation), and it was broadcast during primetime on the most-viewed private national French television channel. And the book continued to act as evidence in a protean, constantly shifting legal trial that lasted for ten years, until the French Supreme Court finally dismissed the false charges of terrorism. But even now, we can’t help but feel that it will never truly end.

So if there was no real legal basis for the case, what was it actually about? In my opinion, it was about the following: that the book has no official author, except for an invisible collective. And it is this fact that calls into question the entire modern structure of literature. What is a book? What is a book without an author? Without visibility? Without rights of ownership? How can we use such a book? Can a book be evidence? Because the modern structure of “the literary” is none other than the modern structure of ownership, or put differently, capitalism’s raison d’être. These are the actual questions that the Tarnac case poses. And they are the fundamental literary questions of the new millennium.

*

If we’re talking about the actual nature of the book, there is another imaginary collective—a collective that is a sort of cousin of the Invisible Committee, that definitely shares some of its authors, it is a collective that is truly literary—I’m talking about the Tiqqun collective, which was making itself heard, and emphatically, well before The Coming Insurrection and the start of the Tarnac case. In November of 1999, they sent a letter to Eric Hazan, the director of the publishing house La Fabrique, which would later publish the Invisible Committee in France. Here’s what they wrote. “Dear Eric, You will find enclosed the new version, largely augmented and divided into sections, of Men-machines, Directions for Use. Despite its appearance, it does not behave like a book, but like a publishing virus.” It’s 1999, the internet’s prehistoric period, before social networks, before blogs, before there was even Myspace. In this prehistoric universe, the 20th century’s nineties, viruses play the starring roles, inhabiting our dreams and our nightmares, they embody a threat, of course, but also a source of liberation; they’re a bit, if you want to think of it this way, like an equivalent to today’s Dark Net. But our imaginary pertaining to the virus is also part of the history of the book, and of literature. For since the sixteenth century, since the Bible materially came to be a printed book, since the development of what historian Benedict Anderson termed Print Capitalism, we have been thinking about the book as an organism, as a healthy or “good” body. And we did this because we were scared of this organism’s other side, which we had since begun to see and to dread. A side that might line up with what Tiqqun calls viruses. Of course, in the 16th century the term virus was not yet in use, but the threat is already there. It’s the threat of what’s underground and disquieting. The fanatic Glenn Beck might even say that it’s devilish. We can already use the word virus in this context because in these early modern times, with the advent of a new technology, the organism could circulate, it could spread, and we didn’t know how to stop it because it was almost beyond all control. We needed a concept to organize all of this. Let’s name it then: It has to do with the book, but not just any book, because there are as many concepts of books as there are concepts of the world. It has to do with the modern version of the book, which is an institution as much as it is an ideology.

It’s in this sense that we can understand the following sentence: “The book is a dead form, in so far as it was holding its reader in the same fraudulent completeness, in the same esoteric arrogance as the classic Subject in front of his peers, no less than the classic figure of ‘Man’.” The book, the subject, and Man, connected in the same network. The Tiqqun writers could say that they are referring implicitly to a text which solidified the modern imaginary of the book, in two pages that are as enlightening as, a priori, they are problematic. A heroic text, as it were. Released more than two hundred years earlier, in 1790. Kant is the author, it is called “What is a book?” and it is part of his work The Science of Right. It is a fascinating text.

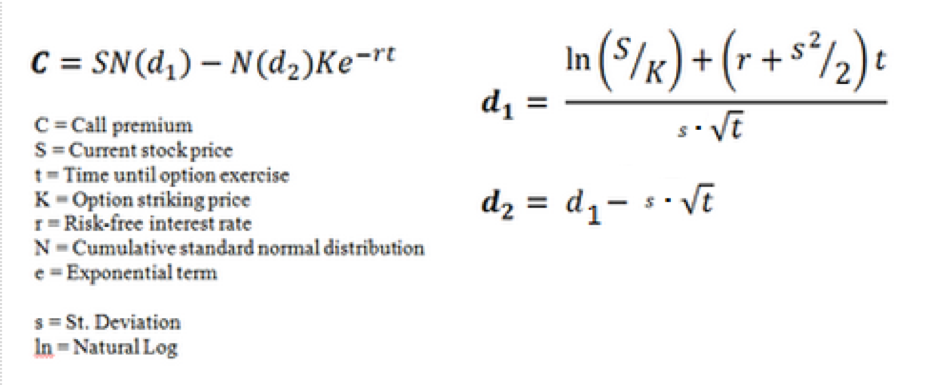

It’s not that Kant revolutionizes everything by himself; he draws from a century of shared reflection. But he condenses and crystallizes. He produces a doctrine of rights intended to put an end to the anarchic situation. Of course he does not want things to go back to the way they were before print capitalism, but he is not at all happy with the way that things are going. It’s all looking too much like the fire that Glenn Beck loves to broadcast at us. Kant’s strategy is impressive in that he disguises his doctrine of rights, wrapping it in an entirely new symbolic architecture, one on which rights will eventually depend. We could say that he produces a fiction dressed up in the attributes of the obvious. For the obvious has already been there for three centuries in Europe at the time when Kant is writing: it is the obviousness of a major technological and capitalist mutation, brought about in large part by the invention of the mechanical press. But, as the historian Roger Chartier has shown, debates that attempt to seize this obviousness are contradictory, dense and disordered. While the mutation has undoubtedly already taken place, Kant is simply intervening with his text to end a debate by proposing a unitary symbolic architecture. He thus asks two questions, which become the two parts of a single legislative text, because they are two sides of the same coin, which is print capitalism. Was ist Geld? Was ist ein Buch? What is money? What is a book? At the end of the eighteenth century, no two questions are more decisive, and they maintain their importance as we move into the beginning of the 21st century. Let’s listen to our hero, here’s what he has to say: “A book is a writing which contains a discourse addressed by someone to the public, through visible signs of speech. It is a matter of indifference to the present considerations whether it is written by a pen or imprinted by types, and on few or many pages.”

You and I, as regrettably materialist as we are, could have responded to the same question with something simpler, something like “a book is an object,” an object that I can hold up in a television studio, for example, in order to say “This is a dangerous book.” At least we could start here, before moving on to something more complex. But that’s exactly what Kant wants to avoid, his entire project is to extract the book from its materiality, and to make it into an abstraction: “It is a matter of indifference to the present considerations whether it is written by pen or imprinted by types, and on few or many pages.” A matter of indifference, therefore, to materiality, which the text only mentions in the phrase “through visible signs of speech,” and we can all agree that that is extremely abstract; as well as an indifference to length, an indifference to action, and a dissimulation of the rupture that the introduction of printing produced; a dissimulation, therefore, of capitalism’s arrival into print. Or rather our hero feigns indifference for he has a hidden agenda: he hopes to cover the book up with another notion, that of speech (“Rede”). An idea that is so central that Kant describes the very person who employs speech, the speaker, as barely anything more than a “someone” (“jemand”). Not yet an author, that will come later, but Kant is logical, first he needs to render abstract the very idea of the author, in order to convert it into what Michel Foucault will later call a function. What is striking here is that he quickly imposes another idea, one that is essential to the creation of the concept of the author: the public.

Here the text does something truly new, as up until this point “the public” referred to only two things: a political entity or the people in attendance at a performance. This new public organized around the book is a strange thing; it is connected to this person, the “someone,” and we still have no idea who this could be. Kant is getting to that. “He who speaks to the public in his own name is the author. He who addresses the writing to the public in the name of the author is the publisher.” Kant certainly knows how to save some of the best things for last. He said “someone” because he had a surprise in mind. “Someone” is not one but two people, both of whom assume speech: the author, but also the publisher who speaks for the author, who is in fact this text’s great conceptual innovation. Or to put it more precisely, Kant invented a symbolic triangle to stand in for the book, a triangle composed of three conceptual figures that were entirely new at the time: the author, the publisher (“Verleger”), and the public. And their relationship was also entirely new, because none of the three could exist without the others, and it is here that we see Kant’s main conceptual invention.

It is significant, because it is an innovation that assumes a unity that stands in opposition to the proliferation of texts, of authorities, and of viruses. The author, the publisher, the public, and the book. We know that until the eighteenth century, literary works in particular were seen as miscellaneous collections that grouped several authors’ contributions together into a single object. One that we could plunder, copy, dismantle, take over. It was rare to associate one author with a text and a book. And if occasionally this did happen, either accidentally or intentionally, then it was vertiginous, like in Don Quixote where the prescience as to what a modern book would be comes from a combination of its obsessive fear, its distancing, its critique. A book was made of multiplicity; a book was a multiplicity that sometimes turned viral. But with Kant, with the move into modernity, with the move away from a caste-based society, in which the political subject is just one specimen of the larger multiplicity, and into a class-based society, in which the political subject is capable of fabricating its own destiny, it was necessary to suppress this proliferation and to impose a unity. So that multiplicity could become profitable, in the economic sense of the term. For the stakes are as much economic as they are philosophical, as it was necessary to transform the book into capitalism’s perfect object. “When a publisher does this with the permission or authority of the author, the act is in accordance with right, and he is the rightful publisher; but if this is done without such permission or authority, that is contrary to right, and the publisher is a counterfeiter or unlawful publisher. The whole of a set of copies of the original document is called an edition.” It’s easier if we read the sentence backwards. Our target is the “set of copies,” now attributable to a sole beneficiary, or more like two beneficiaries, a producer, also known as an author, and the economic agent who enhances the production’s value. We often say that Kant aimed to establish a system of literary ownership, and it’s true, as long as we do not confuse literary ownership with author’s rights. We have a tendency to be blinded by author’s rights, which conceal the rights of yet another agent, the economic agent, the editor. Who nonetheless is never just an economic actor. All of this is, in fact, derived from a certain authority, and an authorization. The economic agent is not just the intermediary in the new symbolic construction around the book, but he is also an agent of authority, because he guarantees authorization. We owe him for the magical transaction that transforms writers into authors and manuscripts into books. He authorizes, he is the author of other authors, the author of authority. Keeping in mind that authority in the context of literature is the expression of a single individuality that brings together a multiplicity. The economic agent is thus much more than we thought: he is a symbolic agent. He is the guardian of capitalism’s magical power, or of the fetishism of merchandise, if you will. And because the book is going to become capitalism’s most fetishized object, the publisher is going to become the book’s head magician.

Do you think I’m exaggerating? Here is Kant again: “A writing is […] a discourse addressed in a particular form to the public”; “and the author may be said to speak publicly by means of his publisher. The publisher, again, speaks by the aid of the printer as his workman (operarius)” and here we need to distinguish between “means” and “aid,” where “aid” refers to the mechanical operation of what has become an entirely immaterial process, “yet not in his own name, for otherwise he would be the author, but in the name of the author; and he is only entitled to do so in virtue of a mandate given him to that effect by the author. Now the unauthorized printer and publisher speaks by an assumed authority in his publication; in the name indeed of the author, but without a mandate to that effect (gerit se mandatarium absque mandato). Consequently, such an unauthorized publication is a wrong committed upon the authorized and only lawful publisher,” and here it is, we understand it now, this “a wrong committed upon” is precisely where the danger is located because dangerous books are above all those that have committed this terrible wrong, “as it amounts to a pilfering of the profits which the latter was entitled and able to draw from the use of his proper right (furtum usus).” A wrong committed against profits, against the very nature of capitalism.

The book is simultaneously material and immaterial; its two-sided nature is the same as that of capitalism, which invests objects with magical qualities by fetishizing them. But thanks to the idea of authority, the book occupies a position at the very top of the hierarchy of merchandise. The book constitutes a separate universe, one that is entirely distinct from action, one without an exterior, its own island of intensity. Following this text’s publication, a debate began among German philosophers who detected a flaw in Kant’s reasoning. How can you determine the owner of a speech? Could ownership be based on the ideas that a speech develops? No, the philosophers will say, ideas belong to everyone; an authorized speech is characterized only by its format. Its “format,” which means style, or the expression of an individual genius. Here we come full circle: the magical unity of this object that is already no longer an object is based on the most immaterial act of appropriation possible, that of style, of individual expression.

*

Now we have a better understanding of Tiqqun and the Tarnac case. We understand why it’s really a literary trial about the very nature of books, which unfolds in the middle of a period that endlessly declares its own crisis. Because a large part of the trial revolved around a question that seems, nonetheless, unfounded: Are you the authors of this book? We also have a better understanding of the irony expressed by a letter to the editor that begins like this, “Despite its appearance it does not behave like a book, but like a publishing virus.” We’re not really talking about moderates and we know it: “The book is a dead form, in so far as it was holding its reader in the same fraudulent completeness, in the same esoteric arrogance as the classic Subject in front of his peers, no less than the classic figure of ‘Man’.” The structure built on unity and completeness trembles, this structure which associates subject, man, and the individual; as Tiqqun’s authors tell us, this structure which is not classic but modern will not hold if its ultimate symbol, the book, loses its identity as a dense block, enclosed, locked, and utopic… if the book opens, instead, to propagation. What follows in the letter is no less suggestive: “The end of institution always perceives itself like the end of an illusion,” rightly characterizing the book as an imaginary institution that is nothing less than the establishing force of the imaginary. “And indeed, it is also the content of truth that causes this outdated thing to be determined a delusion, which then appears as such. So that beyond their character of ending, the great books have never ceased to be those which succeeded in creating a community; in other words, the Book has always had its existence outside of the self, an idea which was only completely accepted fairly recently.”

And here we arrive at the center of what Glenn Beck was so worried about, these weird communities of readers who meet in order to translate The Coming Insurrection or to read it out loud in a coffee shop. These communities that might have, why not?, read the passage in The Coming Insurrection that potentially inspired the sabotage of the train lines, a passage that talks about flows of communication.[1] There are no more clear borders, and this is terrible for Glenn Beck and those like him. By the way, he talks about borders in his sermon, you know the ones, the borders that nice New York liberals want to abolish. The modern book (its enclosed nature as Tiqqun’s writers put it; this stable, institutional and closed site, as Jacques Derrida writes), was designed to be a border between an inside and an outside, between the body and the mind. Within a reality that was a parallelepiped and symbolically triangular, the book formed a world that belonged to it alone, a world that was perfectly symmetrical, where communication, which had become abstract, was a process that took place between an author and a public, with the publisher as its intermediary. According to Tiqqun’s writers, in fact, reality, this cannot hold any longer. It is not the book itself that can no longer hold, but a certain configuration of the book, one that must be reprogrammed. “You are well placed to ascertain that the end of the Book does not signify its brutal disappearance from the social circulation, but on the contrary, its absolute proliferation […] In this phase there are indeed still books, but they are only there to shelter the corrosive effects of PUBLISHING VIRUSES. The publishing virus exposes the principle of incompleteness, the fundamental insufficiency that is in the foundation of the published work. With the most explicit mentions, with the most crudely convenient indications – address, contact, etc.—it increases itself in the sense of realizing the community that it lacks, the virtual community made up of its real-life readers. It suddenly puts the reader in such a position that his withdrawal may no longer be tenable, a position where the withdrawal of the reader can no longer be neutral.” The authors of Tiqqun bring out the big word, community, to tell us something: the book was neutralized during modernity in order to found a community of citizen-consumers of representative democracy. Tiqqun wants to detach the book from this neutralization, to rediscover the savagery characteristic of the end of the eighteenth century.

*

And they succeed in doing this, even before they launch their ships full of explosives, their lead bricks aimed at literature’s soft parts, I mean their three books, The Coming Insurrection, To Our Friends, and Now. In the end maybe Glenn Beck does have the kind of understanding that strikes in dazzling and temporary intuitions. But as he hadn’t read the book yet when he did his broadcast, he couldn’t possibly have known that one of the book’s most scandalous possibilities is the association of the ideal identifier of a literary style, which is to say the idealized expression of a coherent unit, with an imaginary and collective authorship. As if from now on community were possible. This is what makes The Coming Insurrection a dangerous book.

But it wasn’t so visible, when this savagery, this malfunctioning of the modern book, its absolute proliferation became more and more obvious near the beginning of the twenty-first century, as though it was a question of an increasingly natural environment in which we were evolving. Something in the spread of texts and data changed. Like at the end of our hero’s eighteenth century, remember when anarchy reigned, they published anything and everything, translated hastily, borrowed and copied: books become dangerous, they are real viruses that contaminate the sick bodies of traditional monarchies. Books emerge from the body of books, reach public spaces, digital environments, panic-stricken minds.

I don’t know what you’ll think about this but I recently read a statistic which I found far-fetched but also extremely significant. There may be more people who have published something in the twenty years surrounding the new millennium than there have been people published in the entire history of humanity. The fantasmatic bubble of the modern book, that which we owe to Kant, has burst. But, needless to say, the book has survived as it has for the past three thousand years. And it will continue to. In this new millennium, it is less autotelic, it is being reconfigured outside of itself, it is spreading, it is coming back to what it is, a temporary capturing of data, of memories, of imaginaries, of fictions, open to all possible uses. A capturing, a treatment, a production of flows, in a world that is no longer what it was, and that hardly disguises itself in different clothes, state, nation, democracy, but not what brings us together, from European post-democracies to illiberal democracies, from authoritarian regimes to populist democracies, this is what the Invisible Committee stated in To Our Friends, their second book, that used a slogan from the movement against CPE, a proposed liberalization of labor laws targeting young people in 2006: “It’s through flows that this world is maintained. Block everything!” It’s so beautiful that it is hard to believe, especially when we remember the passage from The Coming Insurrection that set off the so-called “Tarnac” case.

Reread the footnote from before: “The technical infrastructure of the metropolis is vulnerable”… The police state wasn’t mistaken when it isolated this passage of the book to get its operations off the ground. The Invisible Committee took hold of the message and shifted the heart of its political analysis from the question of insurrection to the question of flows. “Power is Logistic, Block Everything!” is the title of one chapter in To Our Friends, but this idea comes back all the time, for example here: “There is no world government; what there is instead is a worldwide network of local apparatuses of government, that is, a global, reticular, counterinsurgency machinery.” From one book to another, our political gaze is shifted from the question of democracy to the question of what literary theorist Yves Citton calls mediocracy. Mediocracy or taking over the power of flows, their orientation, their management. Democracies are perhaps nothing more than stories told by mediocracies and fictions are perhaps nothing more than the production of flows. Mediocracy and mythocracy are predicated on each other. And let’s say it, this thing isn’t even new, which doesn’t make it any less interesting. Whenever the Invisible Committee brings up contemporary metropoles, one could just as easily go back 5000 years to when the first cities came into existence, and with them the first writings, and the first totalizing fictions (religions, economies, politics, arts) because the urban world is by nature mediocracy, management of flows, of data, externalization of a memory, quantification, and fictionalization of exchanges in order to produce ties and to maintain order. The whole paradox of literature is that it uses these same tools, that it is exactly pharmakon, poison and antidote. Literary history doesn’t stop telling it to us, telling this story of literary fiction that can save us from fictions of power, but that functions with the same data. One finds it in One Thousand and One Nights, in The Decameron, in Don Quixote. Each one of these works brings to mind a particular moment of mediocracy in which literary fictions are presented as counterfictions. But how do things stand when the mass of flows, of data, is no longer the means by which regimes function but the very heart of governance? How do things stand when media and fiction are developed to such a point that there no longer seem to be any exteriorities?

What happened next proved it. We have found nothing better for this than books, or rather than literature, whether it appears in the guise of books, of publishing viruses or mutant ancient matter. We have found nothing better than counterfictions because, across from them, fiction reigns, whether it feeds itself with the flows of high-speed trains, notes from intelligence agencies or news broadcasts. The so-called “Tarnac” case states code names like hardboiled fiction titles, far-left, anarcho-autonomists, terrorists, interior enemies, these code names soon become government techniques. They invade news broadcasts, mainstream press and bewitch it. But across from them, the look-outs are watching closely. This time, they are called Tiqqun or the Invisible Committee, and their fiction is no less effective. They begin by interrupting flows, then they state their counterfiction, they say that the insurrection is coming, that they are countless and that they do not take the form of a body, but of a virus. Poison versus virus, that’s the equation that is the basis for literary fiction and that justifies it. Power is panic-stricken and reacts violently because nothing terrifies it more than publishing viruses that are opposed to the poison that it instills. Nothing makes it panic more than this multiplicity. In ten years, the look-outs have let go of nothing, in one thousand and one nights of instruction they will have made the fiction of these contemporary Shâriyâr visible and will have made fools of them.

That’s where we were. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the flows were out of control and it was up to us to invest the dangerousness of books and of literary fictions, at times to stop them and to capture them, at times to spread them. To have stated that, and stated it in a book, is what sent nine young people to prison, without any valid motive.

_____

Lionel Ruffel is the author of Brouhaha: Worlds of the Contemporary (Trans. Raymond MacKenzie. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018).

Notes

[1] “The technical infrastructure of the metropolis is vulnerable. Its flows amount to more than the transportation of people and commodities. Information and energy circulates via wire networks, fibers and channels, and these can be attacked. Nowadays sabotaging the social machine with any real effect involves reappropriating and reinventing the ways of interrupting its networks. How can a TGV line or an electrical network be rendered useless? How does one find the weak points in computer networks, or scramble radio waves and fill screens with white noise?”