Seventy years after the horror of Hiroshima, intellectuals negotiate a vastly changed cultural, political and moral geography. Pondering what Hiroshima means for American history and consciousness proves as fraught an intellectual exercise as taking up this critical issue in the years and the decades that followed this staggering inhumanity, albeit for vastly different reasons. Now that we are living in a 24/7 screen culture hawking incessant apocalypse, how we understand Foucault’s pregnant observation that history is always a history of the present takes on a greater significance, especially in light of the fact that historical memory is not simply being rewritten but is disappearing.1 Once an emancipatory pedagogical and political project predicated on the right to study, and engage the past critically, history has receded into a depoliticizing culture of consumerism, a wholesale attack on science, the glorification of military ideals, an embrace of the punishing state, and a nostalgic invocation of the greatest generation. Inscribed in insipid patriotic platitudes and decontextualized isolated facts, history under the reign of neoliberalism has been either cleansed of its most critical impulses and dangerous memories, or it has been reduced to a contrived narrative that sustains the fictions and ideologies of the rich and powerful. History has not only become a site of collective amnesia but has also been appropriated so as to transform “the past into a container full of colorful or colorless, appetizing or insipid bits, all floating with the same specific gravity.”2 Consequently, what intellectuals now have to say about Hiroshima and history in general is not of the slightest interest to nine tenths of the American population. While writers of fiction might find such a generalized, public indifference to their craft, freeing, even “inebriating” as Philip Roth has recently written, for the chroniclers of history it is a cry in the wilderness.3

At same time the legacy of Hiroshima is present but grasped, as the existential anxieties and dread of nuclear annihilation that racked the early 1950s to a contemporary fundamentalist fatalism embodied in collective uncertainty, a predilection for apocalyptic violence, a political economy of disposability, and an expanding culture of cruelty that has fused with the entertainment industry. We’ve not produced a generation of war protestors or government agitators to be sure, but rather a generation of youth who no longer believe they have a future that will be any different from the present.4 That such connections tying the past to the present are lost signal not merely the emergence of a disimagination machine that wages an assault on historical memory, civic literacy, and civic agency. It also points to a historical shift in which the perpetual disappearance of that atomic moment signals a further deepening in our own national psychosis.

If, as Edward Glover once observed, “Hiroshima and Nagasaki had rendered actual the most extreme fantasies of world destruction encountered in the insane or in the nightmares of ordinary people,” the neoliberal disimagination machine has rendered such horrific reality a collective fantasy driven by the spectacle of violence, nourished by sensationalism, and reinforced by scourge of commodified and trivialized entertainment.5 The disimagination machine threatens democratic public life by devaluing social agency, historical memory, and critical consciousness and in doing so it creates the conditions for people to be ethically compromised and politically infantilized. Returning to Hiroshima is not only necessary to break out of the moral cocoon that puts reason and memory to sleep but also to rediscover both our imaginative capacities for civic literacy on behalf of the public good, especially if such action demands that we remember as Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell remark “Every small act of violence, then, has some connection with, if not sanction from, the violence of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”6

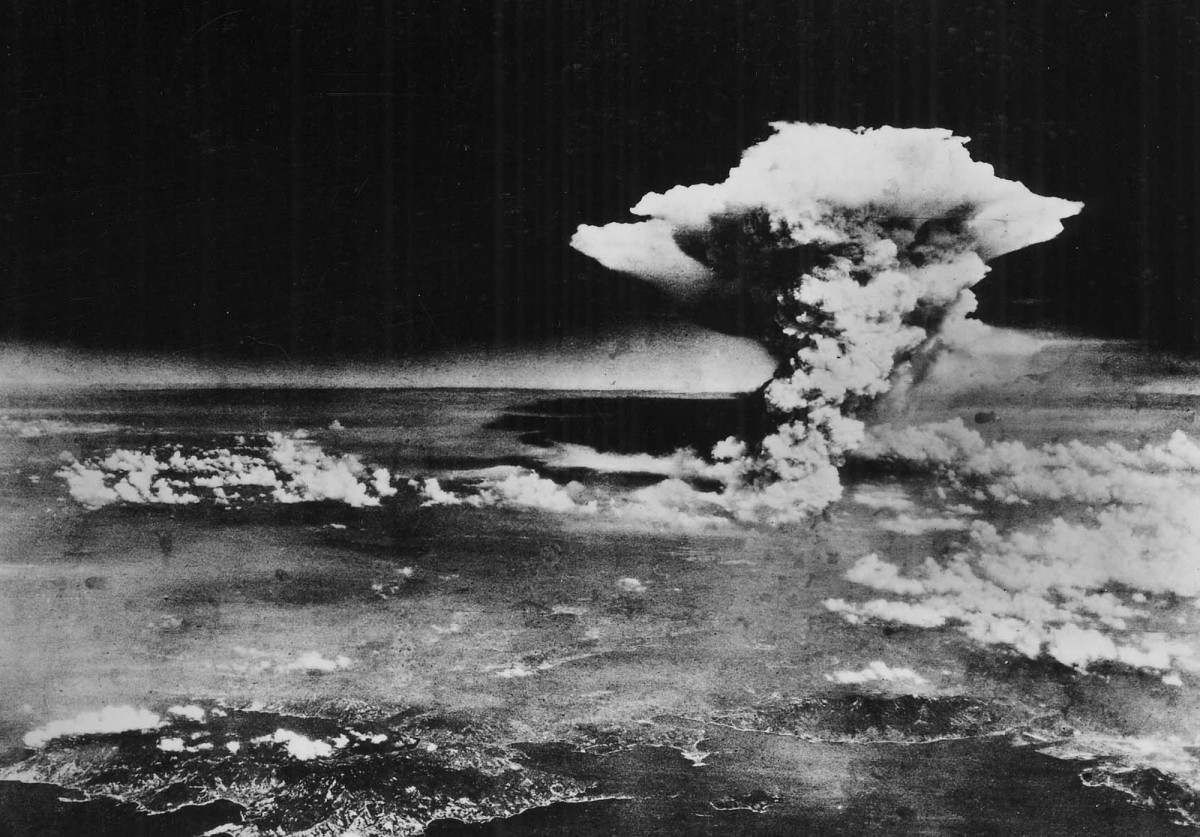

On Monday August 6, 1945 the United States unleashed an atomic bomb on Hiroshima killing 70,000 people instantly and another 70,000 within five years—an opening volley in a nuclear campaign visited on Nagasaki in the days that followed.7 In the immediate aftermath, the incineration of mostly innocent civilians was buried in official government pronouncements about the victory of the bombings of both Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The atomic bomb was celebrated by those who argued that its use was responsible for concluding the war with Japan. Also applauded was the power of the bomb and the wonder of science in creating it, especially “the atmosphere of technological fanaticism” in which scientists worked to create the most powerful weapon of destruction then known to the world.8 Conventional justification for dropping the atomic bombs held that “it was the most expedient measure to securing Japan’s surrender [and] that the bomb was used to shorten the agony of war and to save American lives.”9 Left out of that succinct legitimating narrative were the growing objections to the use of atomic weaponry put forth by a number of top military leaders and politicians, including General Dwight Eisenhower, who was then the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, former President Herbert Hoover, and General Douglas MacArthur, all of whom argued it was not necessary to end the war.10 A position later proven to be correct.

For a brief time, the Atom Bomb was celebrated as a kind of magic talisman entwining salvation and scientific inventiveness and in doing so functioned to “simultaneously domesticate the unimaginable while charging the mundane surroundings of our everyday lives with a weight and sense of importance unmatched in modern times.”11 In spite of the initial celebration of the effects of the bomb and the orthodox defense that accompanied it, whatever positive value the bomb may have had among the American public, intellectuals, and popular media began to dissipate as more and more people became aware of the massive deaths along with suffering and misery it caused.12

Kenzaburo Oe, the Nobel Prize winner for Literature, noted that in spite of attempts to justify the bombing “from the instant the atomic bomb exploded, it [soon] became the symbol of human evil, [embodying] the absolute evil of war.”13 What particularly troubled Oe was the scientific and intellectual complicity in the creation of and in the lobbying for its use, with acute awareness that it would turn Hiroshima into a “vast ugly death chamber.”14 More pointedly, it revealed a new stage in the merging of military actions and scientific methods, indeed a new era in which the technology of destruction could destroy the earth in roughly the time it takes to boil an egg. The bombing of Hiroshima extended a new industrially enabled kind of violence and warfare in which the distinction between soldiers and civilians disappeared and the indiscriminate bombing of civilians was normalized. But more than this, the American government exhibited a ‘total embrace of the atom bomb,” that signalled support for the first time of a “notion of unbounded annihilation [and] “the totality of destruction.”15

Hiroshima designated the beginning of the nuclear era in which as Oh Jung points out “Combatants were engaged on a path toward total war in which technological advances, coupled with the increasing effectiveness of an air strategy, began to undermine the ethical view that civilians should not be targeted… This pattern of wholesale destruction blurred the distinction between military and civilian casualties.”16 The destructive power of the bomb and its use on civilians also marked a turning point in American self-identity in which the United States began to think of itself as a superpower, which as Robert Jay. Lifton points out refers to “a national mindset–put forward strongly by a tight-knit leadership group–that takes on a sense of omnipotence, of unique standing in the world that grants it the right to hold sway over all other nations.”17 The power of the scientific imagination and its murderous deployment gave birth simultaneously to the American disimagination machine with its capacity to rewrite history in order to render it an irrelevant relic best forgotten.

What remains particularly ghastly about the rationale for dropping two atomic bombs was the attempt on the part of its defenders to construct a redemptive narrative through a perversion of humanistic commitment, of mass slaughter justified in the name of saving lives and winning the war.18 This was a humanism under siege, transformed into its terrifying opposite and placed on the side of what Edmund Wilson called the Faustian possibility of a grotesque “plague and annihilation.”19 In part, Hiroshima represented the achieved transcendence of military metaphysics now a defining feature of national identity, its more poisonous and powerful investment in the cult of scientism, instrumental rationality, and technological fanaticism—and the simultaneous marginalization of scientific evidence and intellectual rigour, even reason itself. That Hiroshima was used to redefine America’s “national mission and its utopian possibilities”20 was nothing short of what the late historian Howard Zinn called a “devastating commentary on our moral culture.”21 More pointedly it serves as a grim commentary on our national sanity. In most of these cases, matters of morality and justice were dissolved into technical questions and reductive chauvinism relating matters of governmentally massaged efficiency, scientific “expertise”, and American exceptionalism. As Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell stated, the atom bomb was symbolic of the power of post-war America rather than a “ruthless weapon of indiscriminate destruction” which conveniently put to rest painful questions concerning justice, morality, and ethical responsibility. They write:

Our official narrative precluded anything suggesting atonement. Rather the bomb itself had to be “redeemed”: As “a frightening manifestation of technological evil … it needed to be reformed, transformed, managed, or turned into the vehicle of a promising future,” [as historian M. Susan] Lindee argued. “It was necessary, somehow, to redeem the bomb.” In other words, to avoid historical and moral responsibility, we acted immorally and claimed virtue. We sank deeper, that is, into moral inversion.22

This narrative of redemption was soon challenged by a number of historians who argued that the dropping of the atom bomb had less to do with winning the war than with an attempt to put pressure on the Soviet Union to not expand their empire into territory deemed essential to American interests.23 Protecting America’s superiority in a potential Soviet-American conflict was a decisive factor in dropping the bomb. In addition, the Truman administration needed to provide legitimation to Congress for the staggering sums of money spent on the Manhattan Project in developing the atomic weapons program and for procuring future funding necessary to continue military appropriations for ongoing research long after the war ended.24 Howard Zinn goes even further asserting that the government’s weak defense for the bombing of Hiroshima was not only false but was complicitous with an act of terrorism. Refusing to relinquish his role as a public intellectual willing to hold power accountable, he writes “Can we … comprehend the killing of 200,000 people to make a point about American power?”25 A number of historians, including Gar Alperowitz and Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, also attempted to deflate this official defense of Hiroshima by providing counter-evidence that the Japanese were ready to surrender as a result of a number of factors including the nonstop bombing of 26 cities before Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the success of the naval and military blockade of Japan, and the Soviet’s entrance into the war on August 9th.26

The narrative of redemption and the criticism it provoked are important for understanding the role that intellectuals assumed at this historical moment to address what would be the beginning of the nuclear weapons era and how that role for critics of the nuclear arms race has faded somewhat at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Historical reflection on this tragic foray into the nuclear age reveals the decades long dismantling of a culture’s infrastructure of ideas, its growing intolerance for critical thought in light of the pressures placed on media, on universities and increasingly isolated intellectuals to support comforting mythologies and official narratives and thus cede the responsibility to give effective voice to unpopular realities.

Within a short time after the dropping of the atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, John Hersey wrote a devastating description of the misery and suffering caused by the bomb. Removing the bomb from abstract arguments endorsing matters of technique, efficiency, and national honor, Hersey first published in The New Yorker and later in a widely read book an exhausting and terrifying description of the bombs effects on the people of Hiroshima, portraying in detail the horror of the suffering caused by the bomb. There is one haunting passage that not only illustrates the horror of the pain and suffering, but also offers a powerful metaphor for the blindness that overtook both the victims and the perpetrators. He writes:

On his way back with the water, [Father Kleinsorge] got lost on a detour around a fallen tree, and as he looked for his way through the woods, he heard a voice ask from the underbrush, ‘Have you anything to drink?’ He saw a uniform. Thinking there was just one soldier, he approached with the water. When he had penetrated the bushes, he saw there were about twenty men, they were all in exactly the same nightmarish state: their faces were wholly burned, their eye sockets were hollow, the fluid from their melted eyes had run down their cheeks. Their mouths were mere swollen, pus-covered wounds, which they could not bear to stretch enough to admit the spout of the teapot.27

The nightmarish image of fallen soldiers staring with hollow sockets, eyes liquidated on cheeks and mouths swollen and pus-filled stands as a warning to those who would refuse blindly the moral witnessing necessary to keep alive for future generations the memory of the horror of nuclear weapons and the need to eliminate them. Hersey’s literal depiction of mass violence against civilians serves as a kind of mirrored doubling, referring at one level to nations blindly driven by militarism and hyper-nationalism. At another level, perpetrators become victims who soon mimic their perpetrators, seizing upon their own victimization as a rationale to become blind to their own injustices.

Pearl Harbor enabled Americans to view themselves as the victims but then assumed the identity of the perpetrators and became willfully blind to the United States’ own escalation of violence and injustice. Employing both a poisonous racism and a weapon of mad violence against the Japanese people, the US government imagined Japan as the ultimate enemy, and then pursued tactics that blinded the American public to its own humanity and in doing so became its own worst enemy by turning against its most cherished democratic principles. In a sense, this self-imposed sightlessness functioned as part of what Jacques Derrida once called a societal autoimmune response, one in which the body’s immune system attacked its own bodily defenses.28 Fortunately, this state of political and moral blindness did not extend to a number of critics for the next fifty years who railed aggressively against the dropping of the atomic bombs and the beginning of the nuclear age.

Responding to Hersey’s article on the bombing of Hiroshima published in The New Yorker, Mary McCarthy argued that he had reduced the bombing to the same level of journalism used to report natural catastrophes such as “fires, floods, and earthquakes” and in doing so had reduced a grotesque act of barbarism to “a human interest story” that had failed to grasp the bomb’s nihilism, and the role that “bombers, the scientists, the government” and others played in producing this monstrous act.29 McCarthy was alarmed that Hersey had “failed to consider why it was used, who was responsible, and whether it had been necessary.”30 McCarthy was only partly right. While it was true that Hersey didn’t tackle the larger political, cultural and social conditions of the event’s unfolding, his article provided one of the few detailed reports at the time of the horrors the bomb inflicted, stoking a sense of trepidation about nuclear weapons along with a modicum of moral outrage over the decision to drop the bomb—dispositions that most Americans had not considered at the time. Hersey was not alone. Wilfred Burchett, writing for the London Daily Express, was the first journalist to provide an independent account of the suffering, misery, and death that engulfed Hiroshima after the bomb was dropped on the city. For Burchett, the cataclysm and horror he witnessed first-hand resembled a vision of hell that he aptly termed “the Atomic Plague.” He writes:

Hiroshima does not look like a bombed city. It looks as if a monster steamroller had passed over it and squashed it out of existence. I write these facts as dispassionately as I can in the hope that they will act as a warning to the world. In this first testing ground of the atomic bomb I have seen the most terrible and frightening desolation in four years of war. It makes a blitzed Pacific island seem like an Eden. The damage is far greater than photographs can show.31

In the end in spite of such accounts, fear and moral outrage did little to put an end to the nuclear arms race, but it did prompt a number of intellectuals to enter into the public realm to denounce the bombing and the ongoing advance of a nuclear weapons program and the ever-present threat of annihilation it posed. In the end, fear and moral outrage did little to put an end to the nuclear arms race, but it did prompt a number of intellectuals to enter into the public realm to denounce the bombing and the ongoing advance of a nuclear weapons program and the ever-present threat of annihilation it posed.

A number of important questions emerge from the above analysis, but two issues in particular stand out for me in light of the role that academics and public intellectuals have played in addressing the bombing of Hiroshima and the emergence of a nuclear weapons on a global scale, and the imminent threat of human annihilation posed by the continuing existence and danger posed by the potential use of such weapons. The first question focuses on what has been learned from the bombing of Hiroshima and the second question concerns the disturbing issue of how violence and hence Hiroshima itself have become normalized in the collective American psyche.

In the aftermath of the bombing of Hiroshima, there was a major debate not just about how the emergence of the atomic age and the moral, economic, scientific, military, and political forced that gave rise to it. There was also a heated debate about the ways in which the embrace of the atomic age altered the emerging nature of state power, gave rise to new forms of militarism, put American lives at risk, created environmental hazards, produced an emergent surveillance state, furthered the politics of state secrecy, and put into play a series of deadly diplomatic crisis, reinforced by the logic of brinkmanship and a belief in the totality of war.32

Hiroshima not only unleashed immense misery, unimaginable suffering, and wanton death on Japanese civilians, it also gave rise to anti-democratic tendencies in the United States government that put the health, safety, and liberty of the American people at risk. Shrouded in secrecy, the government machinery of death that produced the bomb did everything possible to cover up the most grotesque effects of the bomb on the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki but also the dangerous hazards it posed to the American people. Lifton and Mitchell argue convincingly that if the development of the bomb and its immediate effects were shrouded in concealment by the government that before long concealment developed into a cover up marked by government lies and the falsification of information.33 With respect to the horrors visited upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki, films taken by Japanese and American photographers were hidden for years from the American public for fear that they would create both a moral panic and a backlash against the funding for nuclear weapons.34 For example, the Atomic Energy Commission lied about the extent and danger of radiation fallout going so far as to mount a campaign claiming that “fallout does not constitute a serious hazard to any living thing outside the test site.”35 This act of falsification took place in spite of the fact that thousands of military personal were exposed to high levels of radiation within and outside of the test sites.

In addition, the Atomic Energy Commission in conjunction with the Departments of Defense, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, the Central Intelligence Agency, and other government departments engaged in a series of medical experiments designed to test the effects of different levels radiation exposure on military personal, medical patients, prisoners, and others in various sites. According to Lifton and Mitchell, these experiments took the shape of exposing people intentionally to “radiation releases or by placing military personnel at or near ground zero of bomb tests.”36 It gets worse. They also note that “from 1945 through 1947, bomb-grade plutonium injections were given to thirty-one patients [in a variety of hospitals and medical centers] and that all of these “experiments were shrouded in secrecy and, when deemed necessary, in lies….the experiments were intended to show what type or amount of exposure would cause damage to normal, healthy people in a nuclear war.”37 Some of the long lasting legacies of the birth of the atomic bomb also included the rise of plutonium dumps, environmental and health risks, the cult of expertise, and the subordination of the peaceful development technology to a large scale interest in using technology for the organized production of violence. Another notable development raised by many critics in the years following the launch of the atomic age was the rise of a government mired in secrecy, the repression of dissent, and the legitimation for a type of civic illiteracy in which Americans were told to leave “the gravest problems, military and social, completely in the hands of experts and political leaders who claimed to have them under control.”38

All of these anti-democratic tendencies unleashed by the atomic age came under scrutiny during the latter half of the twentieth century. The terror of a nuclear holocaust, an intense sense of alienation from the commanding institutions of power, and deep anxiety about the demise of the future spawned growing unrest, ideological dissent, and massive outbursts of resistance among students and intellectuals all over the globe from the sixties until the beginning of the twenty-first century calling for the outlawing of militarism, nuclear production and stockpiling, and the nuclear propaganda machine. Literary writers extending from James Agee to Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. condemned the death-saturated machinery launched by the atomic age. Moreover, public intellectuals from Dwight Macdonald and Bertrand Russell to Helen Caldicott, Ronald Takaki, Noam Chomsky, and Howard Zinn, fanned the flames of resistance to both the nuclear arms race and weapons as well as the development of nuclear technologies. Others such as George Monbiot, an environmental activist, have supported the nuclear industry but denounced the nuclear arms race. In doing so, he has argued that “The anti-nuclear movement … has misled the world about the impacts of radiation on human health [producing] claims … ungrounded in science, unsupportable when challenged and wildly wrong [and] have done other people, and ourselves, a terrible disservice.”39

In addition, in light of the nuclear crises that extend from the Three Mile accident in 1979, the Chernobyl disaster in 1986 and the more recent Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011, a myriad of social movements along with a number of mass demonstrations against nuclear power have developed and taken place all over the world.40 While deep moral and political concerns over the legacy of Hiroshima seemed to be fading in the United States, the tragedy of 9/11 and the endlessly replayed images of the two planes crashing into the twin towers of the World Trade Center resurrected once again the frightening image of what Colonel Paul Tibbetts, Jr., the Enola Gay’s pilot, referred to as “that awful cloud… boiling up, mushrooming, terrible and incredibly tall” after “Little Boy,” a 700-pound uranium bomb was released over Hiroshima. Though this time, collective anxieties were focused not on the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and its implications for a nuclear Armageddon but on the fear of terrorists using a nuclear weapon to wreak havoc on Americans. But a decade later even that fear, however parochially framed, seems to have been diminished if not entirely, erased even though it has produced an aggressive attack on civil liberties and given even more power to an egregious and dangerous surveillance state.

Atomic anxiety confronts a world in which 9 states have nuclear weapons and a number of them such as North Korea, Pakistan, and India have threatened to use them. James McCluskey points out that “there are over 20,0000 nuclear weapons in existence, sufficient destructive power to incinerate every human being on the planet three times over [and] there are more than 2000 held on hair trigger alert, already mounted on board their missiles and ready to be launched at a moment’s notice.”41 These weapons are far more powerful and deadly than the atomic bomb and the possibility that they might be used, even inadvertently, is high. This threat becomes all the more real in light of the fact that the world has seen a history of miscommunications and technological malfunctions, suggesting both the fragility of such weapons and the dire stupidity of positions defending their safety and value as a nuclear deterrent.42 The 2014 report, To Close for Comfort—Cases of Near Nuclear Use and Options for Policy not only outlines a history of such near misses in great detail, it also makes terrifyingly clear that “the risk associated with nuclear weapons is high.”43 It is also worth noting that an enormous amount of money is wasted to maintain these weapons and missiles, develop more sophisticated nuclear weaponries, and invest in ever more weapons laboratories. McCluskey estimates world funding for such weapons at $1trillion per decade while Arms Control Today reported in 2012 that yearly funding for U.S. nuclear weapons activity was $31 billion.44

In the United States, the mushroom cloud connected to Hiroshima is now connected to much larger forces of destruction, including a turn to instrumental reason over moral considerations, the normalization of violence in America, the militarization of local police forces, an attack on civil liberties, the rise of the surveillance state, a dangerous turn towards state secrecy under President Obama, the rise of the carceral state, and the elevation of war as a central organizing principle of society. Rather than stand in opposition to preventing a nuclear mishap or the expansion of the arms industry, the United States places high up on the list of those nations that could trigger what Amy Goodman calls that “horrible moment when hubris, accident or inhumanity triggers the next nuclear attack.”45 Given the history of lies, deceptions, falsifications, and retreat into secrecy that characterizes the American government’s strangulating hold by the military-industrial-surveillance complex, it would be naïve to assume that the U.S. government can be trusted to act with good intentions when it comes to matters of domestic and foreign policy. State terrorism has increasingly become the DNA of American governance and politics and is evident in government cover ups, corruption, and numerous acts of bad faith. Secrecy, lies, and deception have a long history in the United States and the issue is not merely to uncover such instances of state deception but to connect the dots over time and to map the connections, for instance, between the actions of the NSA in the early aftermath of the attempts to cover up the inhumane destruction unleashed by the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the role the NSA and other intelligence agencies play today in distorting the truth about government policies while embracing an all-compassing notion of surveillance and squelching of civil liberties, privacy, and freedom.

Hiroshima symbolizes the fact that the United States commits unspeakable acts making it easier to refuse to rely on politicians, academics, and alleged experts who refuse to support a politics of transparency and serve mostly to legitimate anti-democratic, if not totalitarian policies. Questioning a monstrous war machine whose roots lie in Hiroshima is the first step in declaring nuclear weapons unacceptable ethically and politically. This suggests a further mode of inquiry that focuses on how the rise of the military-industrial complex contributes to the escalation of nuclear weapons and what can we learn by tracing it roots to the development and use of the atom bomb. Moreover, it raises questions about the role played by intellectuals both in an out of the academy in conspiring to build the bomb and hide its effects from the American people? These are only some of the questions that need to be made visible, interrogated, and pursued in a variety of sites and public forums.

One crucial issue today is what role might intellectuals and matters of civic courage, engaged citizenship, and the educative nature of politics play as part of a sustained effort to resurrect the memory of Hiroshima as both a warning and a signpost for rethinking the nature of collective struggle, reclaiming the radical imagination, and producing a sustained politics aimed at abolishing nuclear weapons forever? One issue would be to revisit the conditions that made Hiroshima and Nagasaki possible, to explore how militarism and a kind of technological fanaticism merged under the star of scientific rationality. Another step forward would be to make clear what the effects of such weapons are, to disclose the manufactured lie that such weapons make us safe. Indeed, this suggests the need for intellectuals, artists, and other cultural workers to use their skills, resources, and connections to develop massive educational campaigns.

Such campaigns not only make education, consciousness, and collective struggle the center of politics, but also systemically work to both inform the public about the history of such weapons, the misery and suffering they have caused, and how they benefit the financial, government, and corporate elite who make huge amounts of money off the arms race and the promotion of nuclear deterrence and the need for a permanent warfare state. Intellectuals today appear numbed by ever developing disasters, statistics of suffering and death, the Hollywood disimagination machine with its investment in the celluloid Apocalypse for which only superheroes can respond, and a consumer culture that thrives on self-interests and deplores collective political and ethical responsibility.

There are no rationales or escapes from the responsibility of preventing mass destruction due to nuclear annihilation; the appeal to military necessity is no excuse for the indiscriminate bombing of civilians whether in Hiroshima or Afghanistan. The sense of horror, fear, doubt, anxiety, and powerless that followed Hiroshima and Nagasaki up until the beginning of the 21st century seems to have faded in light of both the Hollywood apocalypse machine, the mindlessness of celebrity and consumer cultures, the growing spectacles of violence, and a militarism that is now celebrated as one of the highest ideals of American life. In a society governed by militarism, consumerism, and neoliberal savagery, it has become more difficult to assume a position of moral, social, and political responsibility, to believe that politics matters, to imagine a future in which responding to the suffering of others is a central element of democratic life. When historical memory fades and people turn inward, remove themselves from politics, and embrace cynicism over educated hope, a culture of evil, suffering, and existential despair. Americans now life amid a culture of indifference sustained by an endless series of manufactured catastrophes that offer a source of entertainment, sensation, and instant pleasure.

We live in a neoliberal culture that subordinates human needs to the demand for unchecked profits, trumps exchange values over the public good, and embraces commerce as the only viable model of social relations to shape the entirety of social life. Under such circumstances, violence becomes a form of entertainment rather than a source of alarm, individuals no longer question society and become incapable of translating private troubles into larger public considerations. In the age following the use of the atom bomb on civilians, talk about evil, militarism, and the end of the world once stirred public debate and diverse resistance movements, now it promotes a culture of fear, moral panics, and a retreat into the black hole of the disimagination machine. The good news is that neoliberalism now makes clear that it cannot provide a vision to sustain society and works largely to destroy it. It is a metaphor for the atom bomb, a social, political, and moral embodiment of global destruction that needs to be stopped before it is too late. The future will look much brighter without the glow of atomic energy and the recognition that the legacy of death and destruction that extends from Hiroshima to Fukushima makes clear that no one can be a bystander if democracy is to survive.

notes:

1. This reference refers to a collection of interviews with Michel Foucault originally published by Semiotext(e). Michel Foucault, “What our present is?” Foucault Live: Collected Interviews, 1961–1984, ed. Sylvere Lotringer, trans. Lysa Hochroth and John Johnston,(New York: Semiotext(e), 1989 and 1996), 407–415.

Back to the essay

2. Zygmunt Bauman and Leonidas Donskis, Moral Blindness: The loss of Sensitivity in Liquid Modernity, (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2013), p. 33.

Back to the essay

3. Daniel Sandstrom Interviews Philip Roth, “My Life as a Writer,” New York Times (March 2, 2014). Online: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/16/books/review/my-life-as-a-writer.html

Back to the essay

4. Of course, the Occupy Movement in the United States and the Quebec student movement are exceptions to this trend. See, for instance, David Graeber, The Democracy Project: A History, A Crisis, A Movement, (New York, NY,: The Random House Publishing Group, 2013) and Henry A. Giroux, Neoliberalism’s War Against Higher Education (Chicago: Haymarket, 2014).

Back to the essay

5. Of course, the Occupy Movement in the United States and the Quebec student movement are exceptions to this trend. See, for instance, David Graeber, The Democracy Project: A History, A Crisis, A Movement, (New York, NY,: The Random House Publishing Group, 2013) and Henry A. Giroux, Neoliberalism’s War Against Higher Education (Chicago: Haymarket, 2014).

Back to the essay

6. Ibid., Lifton and Mitchell, p. 345.

Back to the essay

7. Jennifer Rosenberg, “Hiroshima and Nagasaki (Part 2),” About.com –20th Century History (March 28, 201). Online: http://history1900s.about.com/od/worldwarii/a/hiroshima_2.htm. A more powerful atom bomb was dropped on Nagasaki on August 9, 1945 and by the end of the year an estimated 70,000 had been killed. For the history of the making of the bomb, see the monumental: Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb, Anv Rep edition (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2012.

Back to the essay

8. The term “technological fanaticism” comes from Michael Sherry who suggested that it produced an increased form of brutality. Cited in Howard Zinn, The Bomb. (New York. N.Y.: City Lights, 2010), pp. 54-55.

Back to the essay

9. Oh Jung, “Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Decision to Drop the Bomb,” Michigan Journal of History Vol 1. No. 2 (Winter 2002). Online:

http://michiganjournalhistory.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/oh_jung.pdf.

Back to the essay

10. See, in particular, Ronald Takaki, Hiroshima: Why America Dropped the Atomic Bomb, (Boston: Back Bay Books, 1996). http://michiganjournalhistory.files.wordpress.com/2014/02/oh_jung.pdf.

Back to the essay

11. Peter Bacon Hales, Outside the Gates of Eden: The Dream Of America From Hiroshima To Now. (Chicago. IL.: University of Chicago Press, 2014), p. 17.

Back to the essay

12. Paul Ham, Hiroshima Nagasaki: The Real Story of the Atomic Bombings and Their Aftermath (New York: Doubleday, 2011).

Back to the essay

13. Kensaburo Oe, Hiroshima Notes (New York: Grove Press, 1965), p. 114.

Back to the essay

14. Ibid., Oe, Hiroshima Notes, p. 117.

Back to the essay

15. Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell, Hiroshima in America, (New York, N.Y.: Avon Books, 1995). p. 314-315. 328.

Back to the essay

16. Ibid., Oh Jung, “Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Decision to Drop the Bomb.”

Back to the essay

17. Robert Jay Lifton, “American Apocalypse,” The Nation (December 22, 2003), p. 12.

Back to the essay

18. For an interesting analysis of how the bomb was defended by the New York Times and a number of high ranking politicians, especially after John Hersey’s Hiroshima appeared in The New Yorker, see Steve Rothman, “The Publication of “Hiroshima” in The New Yorker,” Herseyheroshima.com, (January 8, 1997). Online: http://www.herseyhiroshima.com/hiro.php

Back to the essay

19. Wilson cited in Lifton and Mitchell, Hiroshima In America, p. 309.

Back to the essay

20. Ibid., Peter Bacon Hales, Outside The Gates of Eden: The Dream Of America From Hiroshima To Now, p. 8.

Back to the essay

21. Ibid., Zinn, The Bomb, p. 26.

Back to the essay

22. Ibid., Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell, Hiroshima In America.

Back to the essay

23. For a more recent articulation of this argument, see Ward Wilson, Five Myths About Nuclear Weapons (new York: Mariner Books, 2013).

Back to the essay

24. Ronald Takaki, Hiroshima: Why America Dropped the Atomic Bomb, (Boston: Back Bay Books, 1996), p. 39

Back to the essay

25. Ibid, Zinn, The Bomb, p. 45.

Back to the essay

26. See, for example, Ibid., Haseqawa; Gar Alperowitz’s, Atomic Diplomacy Hiroshima and Potsdam: The Use of the Atomic Bomb and the American Confrontation with Soviet Power (London: Pluto Press, 1994) and also Gar Alperowitz, The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb (New York: Vintage, 1996). Ibid., Ham.

Back to the essay

27. John Hersey, Hiroshima (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1946), p. 68.

Back to the essay

28. Giovanna Borradori, ed, “Autoimmunity: Real and Symbolic Suicides–a dialogue with Jacques Derrida,” in Philosophy in a Time of Terror: Dialogues with Jurgen Habermas and Jacques Derrida (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), pp. 85-136.

Back to the essay

29. Mary McCarthy, “The Hiroshima “New Yorker”,” The New Yorker (November, 1946).

http://americainclass.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/mccarthy_onhiroshima.pdf

Back to the essay

30. Ibid., Ham, Hiroshima Nagasaki, p. 469.

Back to the essay

31. George Burchett & Nick Shimmin, eds. Memoirs of a Rebel Journalist: The Autobiography of Wilfred Burchett, (UNSW Press, Sydney, 2005), p.229.

Back to the essay

32. For an informative analysis of the deep state and a politics driven by corporate power, see Bill Blunden, “The Zero-Sum Game of Perpetual War,” Counterpunch (September 2, 2014). Online: http://www.counterpunch.org/2014/09/02/the-zero-sum-game-of-perpetual-war/

Back to the essay

33. The following section relies on the work of both Lifton and Mitchell, Howard Zinn, and M. Susan Lindee.

Back to the essay

34. Greg Mitchell, “The Great Hiroshima Cover-up,” The Nation, (August 3, 2011). Online:

http://www.thenation.com/blog/162543/great-hiroshima-cover#. Also see, Greg Mitchell, “Part 1: Atomic Devastation Hidden For Decades,” WhoWhatWhy (March 26, 2014). Online: http://whowhatwhy.com/2014/03/26/atomic-devastation-hidden-decades; Greg Mitchell, “Part 2: How They Hid the Worst Horrors of Hiroshima,” WhoWhatWhy, (March 28, 2014). Online:

http://whowhatwhy.com/2014/03/28/part-2-how-they-hid-the-worst-horrors-of-hiroshima/; Greg Mitchell, “Part 3: Death and Suffering, in Living Color,” WhoWhatWhy (March 31, 2014). Online: http://whowhatwhy.com/2014/03/31/death-suffering-living-color/

Back to the essay

35. Ibid., Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell, Hiroshima In America, p. 321.

Back to the essay

36. Ibid., Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell, Hiroshima In America, p. 322.

Back to the essay

37. Ibid. Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell, Hiroshima In America, p. 322-323.

Back to the essay

38. Ibid. Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell, Hiroshima In America, p. 336.

Back to the essay

39. George Monbiot, “Evidence Meltdown,” The Guardian (April 5, 2011). Online: http://www.monbiot.com/2011/04/04/evidence-meltdown/

Back to the essay

40. Patrick Allitt, A Climate of Crisis: America in the Age of Environmentalism (New York: Penguin, 2015); Horace Herring, From Energy Dreams to Nuclear Nightmares: Lessons from the Anti-nuclear Power Movement in the 1970s (Chipping Norton, UK: Jon Carpenter Publishing, 2006; Alain Touraine, Anti-Nuclear Protest: The Opposition to Nuclear Energy in France (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1983); Stephen Croall, The Anti-Nuclear Handbook New York: Random House, 1979). On the decade that enveloped the anti-nuclear moment with a series of crisis, see Philip Jenkins, Decade of Nightmares: The End of the Sixties and the Making of Eighties America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Back to the essay

41. James McCluskey, “Nuclear Crisis: Can the Sane Prevail in Time?” Truthout (June 10, 2014). Online: http://www.truth-out.org/opinion/item/24273

Back to the essay

42. See, for example, the list of crisis, near misses, and nuclear war mongering that characterizes United States foreign policy in the last few decades, see, Noam Chomsky, “How Many Minutes to Midnight? Hiroshima Day 2014.” Truthout (August 5, 2014). Online: http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/25388-how-many-minutes-to-midnight-hiroshima-day-2014

Back to the essay

43. Patricia Lewis, Heather Williams, Benoît Pelopidas and Sasan Aghlani, To Close for Comfort —Cases of Near Nuclear Use and Options for Policy (London: Chatham House, 2014). Online: http://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/files/chathamhouse/home/chatham/public_html/sites/default/files/20140428TooCloseforComfortNuclearUseLewisWilliamsPelopidasAghlani.pdf

Back to the essay

44. Jim McCluskey, “Nuclear Deterrence: The Lie to End All Lies,” Truthout (Oct 29, 2012). Online: http://www.truth-out.org/opinion/item/12381

Back to the essay

45. Amy Goodman, “Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 69 Year Later,” TruthDig (August 6, 2014). Online: http://www.truthdig.com/report/item/hiroshima_and_nagasaki_69_years_later_20140806

Back to the essay