Continuing The Tunisian Dossier edited by R. A. Judy and extending the work of al-Insāniya: Thinking Revolutionaries, b2 a series of extended posts focused on what has been called the “Arab Spring,” Miriam Cooke writes on Qatar. Read her article, “The New Empire,” here.

Category: Special Topics

b2 Focus.

-

Stathis Gourgouris on "The Idolatry Post-Secularism"

Follow Stathis’ careful examination of “Idolatry, Prohibition, Unrepresentability,” here, for free download from the Duke UP site and from the last issue of boundary 2, Antinomies of the Postsecular.

This is a meditation on the assertion by Cornelius Castoriadis that “every religion is idolatry.” Idolatry here is configured beyond the conventional understanding of the idol as a concrete object of worship which works within the logic of representation. In monotheism, even the unrepresentable—or, perhaps, especially the unrepresentable—is an idol, an object of worship that is otherwise silenced by a language that claims to worship a nonobject. In this sense, the prohibition of images in monotheism (Bildverbot) is a highly sophisticated mode of idolatry.

-

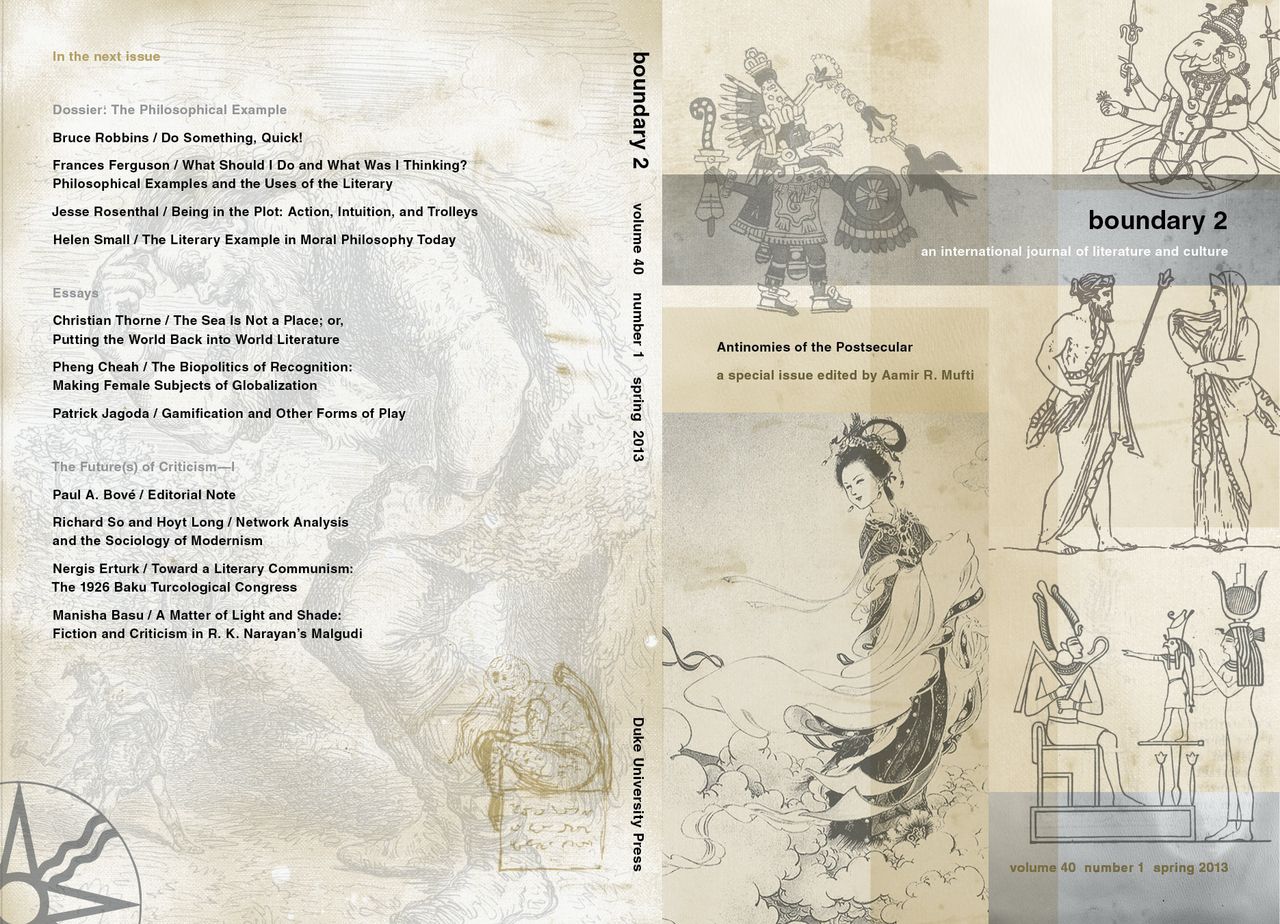

Antinomies of the Postsecular — Why b2 is not postsecular

A new and controversial special issue, Volume 40, Number 1, Spring 2013, has just appeared . . . .In his Introduction to b2‘s special issue, Antinomies of the Postsecular, Aamir Mufti explains his and his colleague’s desire to investigate the surrounding philosophy on this modern “return to religion.”

-

Joseph Cleary, "The History of the Novel and Empire in the Work of Edward Said and Georg Lukács"

Joe Cleary opens b2‘s Legacies of the Future: The Life and Work of Edward Said. Turn up the volume.

__

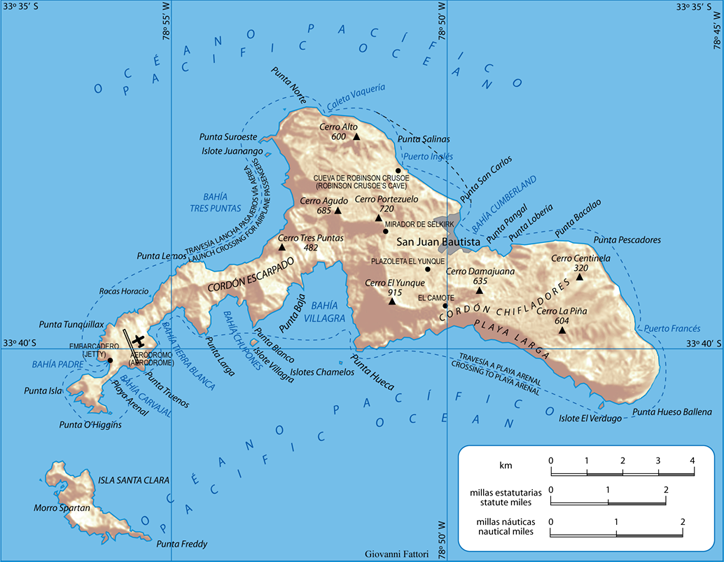

cover photo: Map of Robinson Crusoe Island

-

Aamir Mufti, "The Late Style of Bandung Humanism"

Aamir Mufti brings the historic Bandung Conference into the scope of the conversation. A part of b2‘s series on The Life and Work of Edward Said.

__

cover photo: Gedung Merdeka in Bandung

-

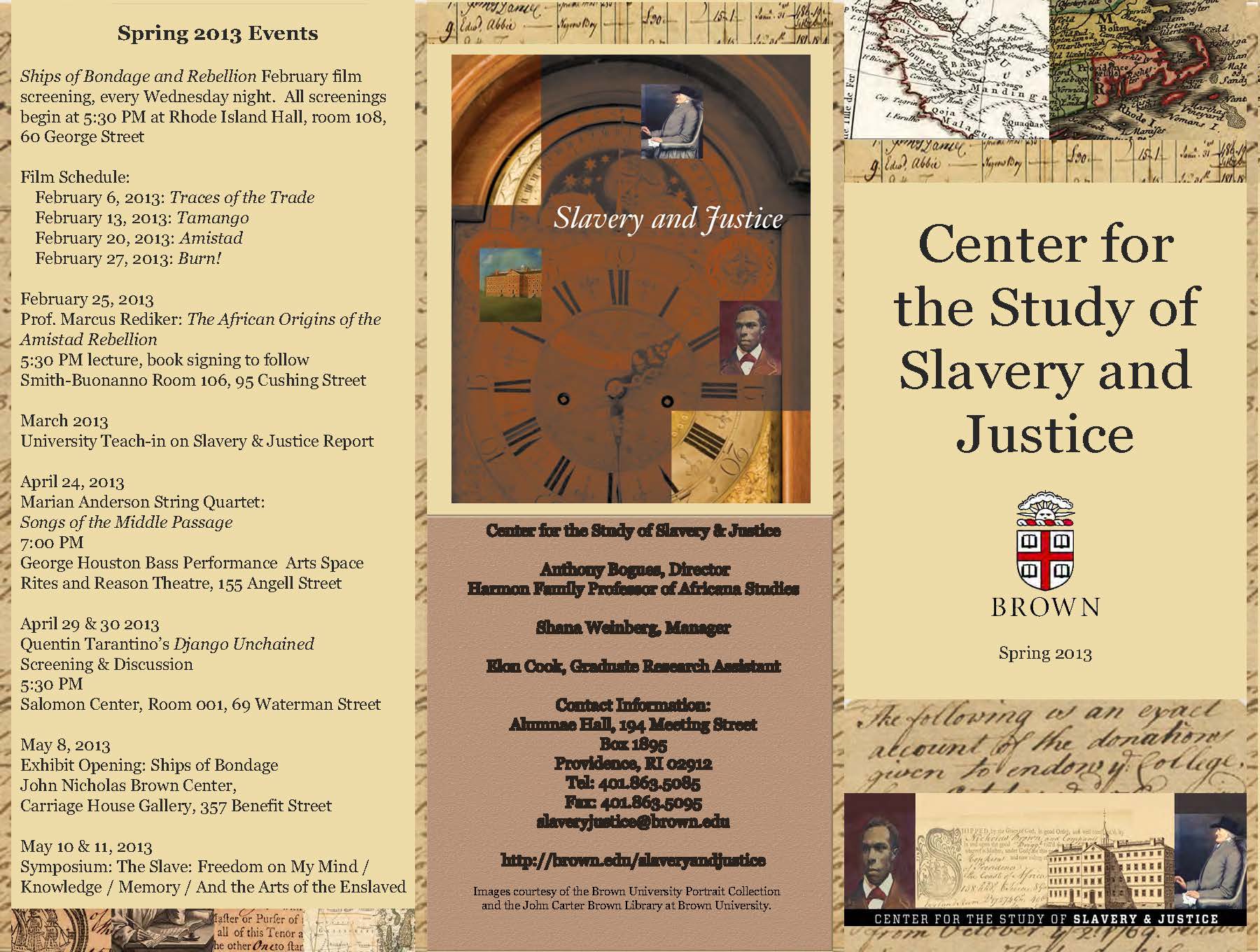

Slavery and Justice

Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice, Brown University

-

Arif Dirlik writes on the University and Global Modernity

Transnationalization and the University: The Perspective of Global Modernity — volume 39, no. 3.

-

Mohamed-Salah Omri's "The upcoming general strike in Tunisia: a historical perspective"

boundary 2 extends the work begun by RA Judy in his important dossier on Tunis.

The upcoming general strike in Tunisia: a historical perspective

by Mohamed-Salah Omri

St, John’s College, OxfordThe first general strikes in Tunisia since 1978 takes place in a much-‐changed country and against old friends but for rather similar reasons. To understand post independence Tunisia, one must get to grips with its labour movement. Successive governments tried to compromise with, co-‐opt, repress or change the union, depending on the situation and the balance of power at hand.

In 1978, the powerful General Union of Tunisian Workers (UGTT) went on general strike to protest what amounted to a coup perpetrated by the Bourguiba government to change a union leadership judged to be too oppositional and too powerful. The cost was the worst setback in the union’s history since the assassination of its founder, the legendary Farhat Hached, in 1952. The entire leadership of the union was put on trial and replaced by regime loyalists. Ensuing popular riots were repressed by the army, resulting in tens of deaths. In few years, however, the formidable trade union would rise gain and continue to play a crucial role as locus of resistance and refuge for activists of all orientations, down to the present time.

UGTT has been the outcome of Tunisian resistance and its incubator at the same time since its founding in 1946. Because of that birth, in the midst of the struggle for liberation from French colonialism, the union had political involvement from the start, a line it has kept and guarded vigorously since. In 1984, it aligned itself with the rioting people during the bread revolt. In 2008, it was the main catalyst of the disobedience movement in the Mining Basin of Gafsa. And come December 2010, UGTT, particularly its teachers’ unions and some regional executives, became the headquarters of revolt against Ben Ali.

After January 2011, UGTT emerged as the key mediator and power broker at the initial phase of the revolution, when all political orientations trusted and needed it. And it was within the union that the committee which regulated the transition to the elections was formed. At the same time, UGTT used its leverage to secure historic victories for its members and for workers in general, including permanent contracts for over 350,000 temporary workers and pay rises for several sectors, including teachers.

Despite various lacunae, UGTT remained democratic throughout. All its bodies were elected freely, even as dictatorship continued to be consolidated over the country as a whole. A combination of symbolic capital of resistance accumulated over decades, a record of results for its members and a well-‐oiled machine at the level of organisation across the country and every sector of the economy, made UGTT unassailable and unavoidable at the same time. But it also became the force to beat for anyone bent on gaining wider control in Tunisia. In other words, as Tunisia moved from the period of revolutionary harmony in which UGTT played host and facilitator, to a political, and even ideological phase, characterised by plurality of parties and polarisation of public opinion, UGTT was challenged to keep its engagement in politics without falling under the control of a particular party or indeed turning into one. But, due to historical reasons, and partly because of the nature of trade unionism in a country such as Tunisia, UGTT remained on the left side of politics and, in the face of

rising Islamist power, became a place where the left, despite its many newly-‐formed parties, kept its ties and even strengthened them. It is no secret that the top leadership of UGTT is largely leftist, or at least progressive in the wide sense of the term. For these reasons, UGTT remained strong and decidedly outside the control of Islamists. This was not for lack of trying, through courtship initially, appeasement afterwards and finally and coercion.

On December the 4th, 2012 as the union was gearing up to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the assassination of its founder, its iconic headquarters, Place Mohamed Ali, was attacked by groups known as Leagues for the Protection of the Revolution. The incident was ugly, public and of immediate impact. These leagues, which originated in community organisation in cities across the country designed to keep order and security immediately after January 14, but were later disbanded, are now dominated by Islamists of various orientations. They have been targeting the media, artists and members of the former regime under the slogans: purification or cleansing of the old regime and protection of the revolution. A prominent action was their violent attack against the party Nida Tounes, headed by former Prime Minister, Beji Qaid Sebsi, which resulted in the first political killing after the revolution, that of Nida member Lotfi Nagadh in the southern town, Tataouine.

UGTT sensed in the attack, which was the latest in a series of actions, such as throwing trash at the unions offices in several regions few months ago, a repeat of 1978 and an attempt against its very existence. It responded by boycotting the government, organizing regional strikes and marches, and eventually calling for a general strike on Thursday the 13th of December, the first such action since

1978. For the first time, UGTT came clearly against Nahdah party and declared it enemy number one after stating on many occasions that it stands at the same distance from all parties. Anti-‐Nahdah parties and individuals are now banking on this and backing UGTT. In Tunisia, contradictions have suddenly sharpened, rather not unlike the situation in Egypt, where President Morsi managed to unite warring opposition groups against his party when he gave himself sweeping powers.

Tunisia today stands divided, with UGTT heading one side and Nahdha on the other. If history is any guide, UGTT will overcome this time as well. What is in doubt is the cost to a revolution plagued by a set of circumstances and developments largely beyond the control of the country. This is also Nahdah’s toughest test, internally and internationally. Internally, UGTT is forcing a rift between the government and the party which dominates it by challenging the former to protect a national organization and apply the rule of law. Internationally, UGTT has already laid bare the para-‐military nature of the Leagues as danger to social peace in Tunisia, on one hand, and rallied the union’s powerful friends in the international labour movement. As the 13th approaches, Tunisia is holding its breath, and everyone is involved in one way or another to head off what could be a collision of titanic proportions.

-

b2 mourns the death of the great critic and musician, Charles Rosen

The winner of the National Humanities Medal, a remarkable performer and scholar of European music, an expert in Modernism, and the author of two important essays on Walter Benjamin, Rosen died December 9, 2012.

See the New York Times obituary here.