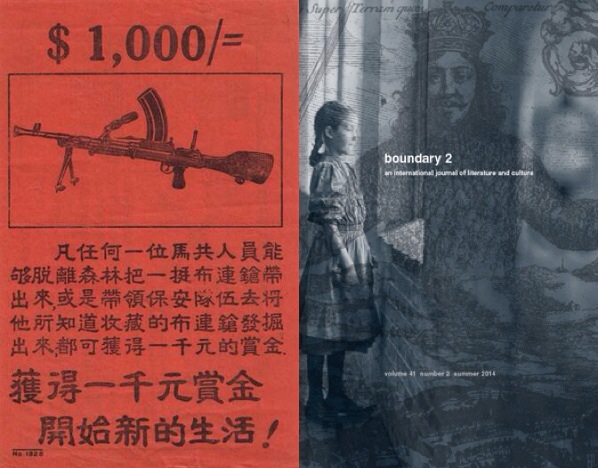

Born in Translation: “China” in the Making of “Zhongguo”

An essay by Arif Dirlik

“The unwillingness to confront tough questions about history and heritage in China cuts into the core of cultural identity” Han Song

_

From the perspective of nationalist historiography and Orientalist mystification alike, it might seem objectionable if not shocking to suggest that China/Zhongguo as we know it today owes not only its name but its self-identification to “the Western” notion of “China.” For good historical reasons, as each has informed the other, the development of China/Zhongguo appears in these perspectives as a sui generis process from mythical origins to contemporary realization. Nationalist historians see the PRC’s developmental success as proof of a cultural exceptionalism with its roots in the distant past. The perception derives confirmation from and in turn re-affirms Orientalist discourses that long have upheld the cultural exceptionality of the so-called “Middle Kingdom.”

From the perspective of nationalist historiography and Orientalist mystification alike, it might seem objectionable if not shocking to suggest that China/Zhongguo as we know it today owes not only its name but its self-identification to “the Western” notion of “China.” For good historical reasons, as each has informed the other, the development of China/Zhongguo appears in these perspectives as a sui generis process from mythical origins to contemporary realization. Nationalist historians see the PRC’s developmental success as proof of a cultural exceptionalism with its roots in the distant past. The perception derives confirmation from and in turn re-affirms Orientalist discourses that long have upheld the cultural exceptionality of the so-called “Middle Kingdom.”

The problematic relationship of China/Zhongguo to its imperial and even more distant pasts is most eloquently evident, however, in the ongoing efforts of nationalist historians in the People’s Republic of China(PRC) to reconnect the present to a past from which it has been driven apart by more than a century of revolutionary transformation. That transformation began in the last years of the Qing Dynasty(1644-1911), when late Qing thinkers settled on an ancient term, Zhongguo, as an appropriate name for the nation-form to supplant the Empire that had run its course. The renaming was directly inspired by the “Western” idea of “China,” that called for radical re-signification of the idea of Zhongguo, the political and cultural space it presupposed, and the identification it demanded of its constituencies. Crucial to its realization was the re-imagination of the past and the present’s relationship to it.

I will discuss briefly below why late Qing intellectuals felt it necessary to rename the country, the inspiration they drew upon, and the spatial and temporal presuppositions of the new idea of China/Zhongguo. Their reasoning reveals the modern origins of historical claims that nationalist historiography has endowed with timeless longevity. I will conclude with some thoughts on the implications of such a deconstructive reading for raising questions about the political assumptions justified by the historical claims of China/ Zhongguo—especially a resurgent Sino-centrism that has been nourished by the economic and political success of the so-called “China Model.” This Sino-centrism feeds cultural parochialism, as well as spatial claims that are imperial if only because they call upon imperial precedents for their justification. 1

Naming China/Zhongguo

My concern with the question of naming began with an increasing sense of discomfort I have felt for some time now with the words “China” and “Chinese” that not only define a field of study, but are also commonplaces of everyday language of communication. The fundamental question these terms throw up is: if, as we well know, the region has been the site for ongoing conflicts over power and control between peoples of different origins, and varied over time in geographical scope and demographic composition, which also left their mark on the many differences within, what does it mean to speak of China(or Zhongguo) or Chinese(Zhongguo ren or huaren), or write the history of the region as “Chinese” history (Zhongguo lishi)?

The discomfort is not idiosyncratic. These terms and the translingual exchanges in their signification have been the subject of considerable scholarly scrutiny in recent years. 2 “China,” a term of obscure origins traced to ancient Persian and Sanskrit sources, since the 16th century has been the most widely used name for the region among foreigners, due possibly to the pervasive influence of the Jesuits who “manufactured” “China” as they did much else about it. 3 The term refers variously to the region(geography), the state ruling the region(politics), and the civilization occupying it(society and culture), which in their bundling abolish the spatial, temporal and social complexity of the region. Similarly, “Chinese” as either noun or predicate suggests demographic and cultural homogeneity among the inhabitants of the region, their politics, society, language, culture and religion. It refers sometimes to all who dwell in the region or hail from it, and at other times to a particular ethnic group, as in “Chinese” and “Tibetans,” both of whom are technically parts of one nation called “China” and, therefore, “Chinese” in a political sense. The term is identified tacitly in most usage with the majority Han, who themselves are homogenized in the process in the erasure of significant intra-Han local differences that have all the marks of ethnic difference. 4 Homogenization easily slips into racialization when the term is applied to populations—as with “Chinese Overseas”– who may have no more in common than origins in the region, where local differences matter a great deal, and their phenotypical attributes, which are themselves subject to variation across the population so named. 5 Equally pernicious is the identification of “China” with the state in daily reporting in headlines that proclaim “China” doing or being all kinds of things, anthropomorphizing “China” into a historical subject abstracted from the social and political relations that constitute it.

The reification of “China” and “Chinese” has temporal implications as well. 6 “Chinese” history constructed around these ideas recognizes the ethnic and demographic complexity in the making of the region, but still assumes history in “China” to be the same as history of “Chinese,” which in a retroactive teleology is extended back to Paleolithic origins. Others appear in the story only to disappear from it without a trace. The paradigm of “sinicization”(Hanhua, tonghua) serves as alibi to evolutionary fictions of “5000-year old” “Chinese” civilization, and even more egregiously, a “Chinese” nation, identified with the Han nationality descended from mythical emperors of old of whom the most familiar to Euro/Americans would be the Yellow Emperor.

One of the most important consequences of the reification of “China” and “Chineseness” was its impact on the identification of the region and the self-identification of its dominant Han nationality. Until the twentieth century, these terms did not have native equivalents. The area was identified with successive ruling dynasties, which also determined the self-identification of its people(as well as identification by neighboring peoples). Available trans-dynastic appellations referred to ethnic, political, and cultural legacies that had shaped the civilizational process in the region but suggested little by way of the national consciousness that subsequently has been read into them. As Lydia Liu has observed, “the English terms `China’ and `Chinese’ do not translate the indigenous terms hua, xia, han, or even zhongguo now or at any given point in history.” 7

Contemporary names for “China,” Zhongguo or Zhonghua have a history of over 2000 years, but they were neither used consistently, nor had the same referents at all times. During the Warring States Period(ca 5th-3rd centuries BC), the terms referred to the states that occupied the central plains of the Yellow River basin that one historian/philologist has described as the “East Asian Heartland.” 8 During the 8th to the 15th centuries, according to Peter Bol, “Zhong guo was a vehicle for both a spatial claim—that there was a spatial area that had a continuous history going back to the `central states’(the zhong guo of the central plain during the Estern Zhou)—and a cultural claim—that there was a continuous culture that had emerged in that place that its inhabitant ought to, but might not, continue, and should be translated preferably as “the Central Country.” 9

Bol’s statement is confirmed by contemporaries of the Ming and the Qing in neighboring states. Even the “centrality” of the Central Country was not necessarily accepted at all times. The Choson Dynasty in Korea, which ruled for almost 500 years(equaling the Ming and Qing put together), long has been viewed as the state most clearly modeled on Confucian principles (and the closest tributary state of the Ming and the Qing). It is worth quoting at some length from a recent study which writes with reference to 17th century Choson Confucian Song Si-yol, resentful of the Qing conquest of the Ming, that,

For Song, disrecognition of Qing China was fundamentally linked to the question of civilization, and as adamant a Ming loyalist as he was, he also made it quite clear that civilization was not permanently tied to place or people. Both Confucius and Mencius, for example, were born in states where previously the region and its people had been considered foreign, or barbaric(tongyi), and Song argued vigorously that it was the duty of learned men in Choson Korea to continue the civilizational legacy that began with the sage kings Yao and Shun, a precious legacy that had been cultivated and transmitted by Confucius, Mencius and Zhu Xi, and taken up by Yi Hwang(Toegye) and Yi I(Yulgok) of Choson Korea. …To reclaim its authority over rituals and discourse on the state of Choson Korea’s civilization, and even as it performed rituals of submission to the Qing, the Choson court took the dramatic step of also establishing a shrine to the Ming…This high-stakes politics over ritual practice helped establish a potent narrative of Choson Korea as so Chunghwa, a lesser civilization compared to Ming China, but after the Manchu conquest of China, the last bastion of civilization. 10

I will say more below on the idea of “Under Heaven”(tianxia) in the ordering of state relations in Eastern Asia. Suffice it to say here that these relations were based not on fealty to “China”(or Zhongguo understood as “China”), but to a civilizational ideal embedded in Zhou Dynasty classics. Even Zhonghua, one of the names for “China” in the 20th century, was portable. It should be evident also that where Choson Confucians were concerned, the sages who laid the foundations for civilization were not “Chinese” but Zhou Dynasty sages whose legacies could be claimed by others against the “central country” itself. Indeed, both the Choson in Korea and the Nguyen Dynasty in Vietnam claimed those legacies even as they fought “central country” dominion. 11

The term Zhongguo(or Zhonghua) assumed its modern meaning as the name for the nation in the late 19th century (used in international treaties, beginning with the Treaty of Nerchinsk with Russia in 1689). Its use “presupposed the existence of a translingual signified `China’ and the fabulation of a super-sign Zhongguo/China.” 12 As Bol puts it more directly,

…in the twentieth century “China/Zhongguo” has become an officially mandated

term for this country as a continuous historical entity from antiquity to the present.

….this modern term, which I shall transcribe as Zhongguo, was deployed in new

ways, as the equivalent of the Western term “China.” In other words the use of

“China” and “Chinese” began as a Western usage; they were then adopted by the

government of the people the West called the “Chinese” to identify their own

country, its culture, language, and population. This took place in the context of

establishing the equality of the country in international relations and creating a

Western-style nation-state, a “China” to which the “Chinese” could be loyal. 13

The idea of Zhongguo as a fiction based on a “Western” invention obviously goes against the claims of a positivist nationalist historiography which would extend it, anachronistically, to the origins of human habitation in the region, and claim both the region’s territory and history as its own. 14 Properly speaking, Zhongguo(or Zhonghua) as the name of the country should be restricted to the political formation(s) that succeeded the last imperial dynasty, the Qing. Even if the modern sense of the term could be read into its historical antecedents, it does not follow that the sense was universally shared in the past, or was transmitted through generations to render it into a political or ideological tradition, or part of popular political consciousness. A recent study by Shi Aidong offers an illuminating(and amusing) account of the translingual and transcultural ironies in the deployment of terms such as “China,” “Chinese,” or Zhongguo. The author writes with reference to the early 16th century Portuguese soldier-merchant Galeoto Pereira, who had the privilege of doing time in a Ming jail, and subsequently related his experiences in one of the earliest seminal accounts of southern China:

Pereira found strangest that Chinese[Zhongguoren] did not know that they were Chinese[Zhongguoren].He says: “We are accustomed to calling this county China and its inhabitants Chins, but when you ask Chinese[Zhongguoren] why they are called this, they say “[We] don’t have this name, never had.” Pereira was very intrigued, and asked again: “What is your entire country called? When someone from another nation asks you what country you are from, what do you answer?” The Chinese[Zhongguoren] thought this a very odd question. In the end, they answered: “In earlier times there were many kingdoms. By now there is only one ruler. But each state still uses its ancient name. These states are the present-day provinces(sheng).The state as a whole is called the Great Ming(Da Ming), its inhabitants are called Great Ming people(Da Ming ren). 15(highlights in the original)

Nearly four centuries later, a late Qing official objected to the use of terms such as “China,” in the process offering a revealing use of “Zhongguo” as little more than a location. The official, Zhang Deyi, complained about the names for China used by Euro/Americans, “who, after decades of East and West diplomatic and commercial interactions, know very well that Zhongguo is called Da Qing Guo[literally, the Great Qing State] or Zhonghua [the Central Efflorescent States]but insist on calling it Zhaina(China), Qina(China), Shiyin(La Chine), Zhina (Shina), Qita(Cathay), etc. Zhongguo has not been called by such a name over four-thousand years of history. I do not know on what basis Westerners call it by these names?” 16

The official, Zhang Deyi, was right on the mark concerning the discrepancy between the names used by foreigners and Qing subjects. Even more striking is his juxtaposition of Qing and Zhongguo. Only a few years later, the distinguished Hakka scholar-diplomat Huang Zunxian would write that, “if we examine the countries(or states, guo) of the globe, such as England or France, we find that they all have names for the whole country. Only Zhongguo does not.” 17Liang Qichao added two decades later( in 1900) that “hundreds of millions of people have maintained this country in the world for several thousand years, and yet to this day they have not got a name for their country.” 18 Zhongguo was not a name of the country, it waited itself to be named.

What then was Zhongguo? A mere “geographical expression,” as Japanese imperialism would claim in the 1930s to justify its invasion of the country? And how would it come to be the name of the country only a decade after Liang wrote of the nameless country where the people’s preference for dynastic affiliation over identification with the country was a fatal weakness that followed from an inability to name where they lived?

By the time late Qing intellectuals took up the issue around the turn of the twentieth-century, diplomatic practice already had established modern notions of China and Chinese, with Zhongguo and Zhongguoren as Chinese-language equivalents. More research is necessary before it is possible to say why Zhongguo had come to be used as the equivalent of China in these practices, and how Qing officials conceived of its relationship to the name of the dynasty. It is quite conceivable that there should have been some slippage over the centuries between Zhong guo as Central State and Zhong guo as the name for the realm, which would also explain earlier instances scholars have discovered of the use of the term in the latter sense. There is evidence of such slippage in Jesuit maps dating back to the early seventeenth century. It does not necessarily follow that the practice of using Zhongguo or Zhonghua alongside dynastic names originated with the Jesuits, or that their practice was adopted by Ming and Qing cartographers. There is tantalizing evidence nevertheless that however hesitant initially, the equivalence between “China” and Zhongguo suggested in Jesuit cartographic practice was directly responsible for the dyadic relationship these terms assumed in subsequent years, beginning with the treaties between the Qing and various Euro/American powers. 19

Matteo Ricci’s famous Map of the World(Imago Mundi) in Chinese from 1602 provides an interesting and perplexing example. The map designates the area south of the Great Wall (“China proper”) as “the Unified Realm of the Great Ming”(Da Ming yitong). 20At the same time, the annotation on Chaoxian(Korea) written into the map notes that during the Han and the Tang, the country has been “a prefecture of Zhongguo,” which could refer to either the state or the realm as a whole–or both as an administrative abstraction—which is likely as the realm as such is named after the dynasty. 21It is also not clear if Ricci owed a debt to his Ming collaborators for the annotation where he stated that the historical predecessors of the contemporary Joseon State had been part of Zhongguo, which explained the close tributary relationship between the Ming and the Joseon. 22 Four centuries later, PRC historical claims to the Goguryeo Kingdom, situated on the present-day borderlands between the two countries for six centuries from the Han to the Tang, would trigger controversy between PRC and South Korean historians over national ownership both of territory and history.

Jesuits who followed in Ricci’s footsteps were even more direct in applying Zhongguo or Zhonghua to dynastic territories. According to a study of Francesco Sambiasi, who arrived in the Ming in shortly after Ricci’s death in 1610, on his own map of the world,

Sambiasi calls China Zhonghua 中華, which is what [Giulio]Aleni uses in his Zhifang waiji, rather than Ricci’s term Da Ming 大明. Aleni, however, is far from consistent. On the map of Asia in his Zhifang waiji he has Da Ming yitong 大明一統, ‘Country of the Great Ming [dynasty]’, for China, and he uses the same name on his map of the world preserved in the Bibliotheca Ambrosiana. On another copy in the Biblioteca Nazionale di Brera, he uses yet another name for China, Da Qing yitong大清一統, ‘Country of the Great Qing [dynasty]. 23

It was in the in the nineteenth century, in the midst of an emergent international order and under pressure from it, that Zhongguo in the singular acquired an unequivocal meaning, referring to a country with a definite territory but also a Chinese nation on the emergence. 24 The new sense of the term was product, in Lydia Liu’s fecund concept, of “translingual encounter.” Already by the 1860s, the new usage had entered the language of Qing diplomacy. The conjoining of China/ Zhongguo in international treaties in translation established equivalence between the two terms, which now referred both to a territory and the state established over that territory. 25 Zhongguo appeared in official documents with increasing frequency, almost interchangeably with Da Qing Guo, and most probably in response to references in foreign documents to China. It no longer referred to a “Central State.” Historical referents for the term were displaced(and, “forgotten”) as it came to denote a single sovereign entity, China. It is not far-fetched to suggest, as Liu has, that it was translation that ultimately rendered Zhongguo into the name of the nation that long had been known internationally by one or another variant of China.

A few illustrations will suffice here. The world map printed in the first Chinese edition of Henry Wheaton’s Elements of International Law in 1864, used the Chinese characters for Zhongguo to identify the region we know as China. 26 Da Qing Guo remained in use as the official appellation for the Qing. For instance, the 19th article of the “Chinese-Peruvian Trade Agreement”(ZhongBi tongshang tiaoyue) in 1869 referred to the signatories as “Da Qing Guo” and “Da Bi Guo.” 27 Without more thorough and systematic analyisis, it is difficult to say what determined choice. It seems perhaps that where reference was to agency, Da Qing Guo was the preferred usage, but this is only an impressionistic observation. More significant for purposes here may be the use of Da Qing Guo and Zhongguo in the very same location and, even more interestingly, the reference further down in the article to Zhongguo ren, or Chinese people.

The extension of Zhongguo to the Hua people abroad is especially signiicant. Zhongguo in this sense overflows its territorial boundaries, which in later years would be evident in the use of such terms as “Da Zhongguo” (Greater China) or “Wenhua Zhongguo” (Cultural China). Even more revealing than the proliferating use of Zhongguo in official documents and memoranda may be the references to “Chinese.” In the documents of the 1860s, Huaren and Huamin are still the most common ways of referring to Chinese abroad and at home (as in Guangdong Huamin). 28 However, the documents are also replete with references to Zhongguo ren(Chinese), Zhongguo gongren(Chinese workers), and, on at least one occasion, to “Biluzhi Zhongguo ren,” literally, “the Chinese of Peru,” which indicates a deterritorialized notion of China on the emergence, that demands recognition and responsibility from the “Chinese” state beyond its boundaries. 29

In its overlap with Hua people, primarily an ethnic category, Zhongguo ren from the beginning assumed a multiplicity of meanings—from ethnic and national to political identity, paralleling some of the same ambiguities characteristic of terms like China and Chinese. Foreign pressure in these treaties– especially US pressure embodied in the Burlingame mission of 1868– played a major part in enjoining the Qing government to take responsibility for Hua populations abroad. The confounding of ethnic, national and political identities confirmed the racialization of hua populations that already was a reality in these foreign contexts by bringing under one collective umbrella people with different national belongings and historical/cultural trajectories.

Late Qing intellectuals such as Liang Qichao and Zhang Taiyan who played a seminal part in the formulation of modern Chinese nationalism were quick to point out shortcomings of the term Zhongguo as a name for the nation. Liang Qichao offered pragmatic reasons for their choice: since neither the inherited practice of dynastic organization nor the foreign understanding ( China, Cathay, etc) offered appropriate alternatives, the use of “Zhongguo” made some sense as most people were familiar with the term. Nearly three decades later the historian Liu Yizheng would offer a similar argument for the use of Zhongguo. 30One historian recently has described the change in the meaning of Zhongguo as both a break with the past, and continuous with it. 31. The contradiction captures the ambivalent relationship of modern China to its past.

Naming the nation was only the first step in “the invention of China.” The next, even more challenging, step was to Sinicize, or more appropriately, make Chinese (Zhongguohua), the land, the people, and the past. Liang Qichao’s 1902 essay, “the New History” appears in this perspective as a program to accomplish this end. As the new idea of “China/Zhongguo” was a product of the encounter with Euromodernity, the latter also provided the tools for achieving this goal. The new discipline of history was one such tool. Others were geography, ethnology, and archeology. History education in the making of “new citizens” was already under way before the Qing was replaced by the Republic, and it has retained its significance to this day. So has geography, intended to bring about a new consciousness of “Chinese” spaces. Archeology, meanwhile, has taken “Chinese” origins ever farther into the past. And ethnology has occupied a special place in the new disciplines of sociology and anthropology because of its relevance to the task of national construction out of ethnic diversity. 32

It was twentieth century nationalist reformulation of the past that would invent a tradition and a nation out of an ambiguous and discontinuous textual lineage. It is noteworthy that despite the most voluminous collection of writing on the past in the whole world, there was no such genre before the twentieth century as Zhongguo lishi (the equivalent of “Chinese” history)—some like Liang Qichao blamed the lack of national consciousness among “Chinese” to the absence of national history. The appearance of the new genre testified to the appearance of a new idea of Zhongguo, and the historical consciousness it inspired. The new history would be crucial in making the past “Chinese”—and, tautologically, legitimize the new national formation. 33

Especially important in constructing national history were the new “comprehensive histories”(tongshi), covering the history of China/ Zhongguo from its origins(usually beginning with the Yellow Emperor whose existence is still very much in doubt) to the present. 34 What distinguished the new “comprehensive histories” from their imperial antecedents was their linear, evolutionary account of the nation as a whole that rendered the earlier dynastic histories into building blocks of a progressive narrative construction of the nation. The first such accounts available to Qing intellectuals were histories composed by Japanese historians. Not surprisingly, the first “comprehensive histories” composed by Qing historians were school textbooks. It is worth quoting at length the conclusion to a 1920 New Style History Textbook that concisely sums up the goals of nationalist historiography from its Qing origins to its present manifestations with Xi Jinping’s “China Dream”:

The history of China is a most glorious history. Since the Yellow Emperor, all the things we rely on—from articles of daily use to the highest forms of culture—have progressed with time. Since the Qin and Han Dynasties created unity on a vast scale, the basis of the state has become ever more stable, displaying China’s prominence in East Asia. Although there have been periods of discord and disunity, and occasions when outside forces have oppressed the country, restoration always soon followed. And precisely because the frontiers were absorbed into the unity of China, foreign groups were assimilated. Does not the constant development of the frontiers show how the beneficence bequeathed us from our ancestors exemplifies the glory of our history? It is a matter of regret that foreign insults have mounted over the last several decades, and records of China’s humiliation are numerous. However, that which is not forgotten from the past, may teach us for the future. Only if all the people living in China love and respect our past history and do their utmost to maintain its honor, will the nation be formed out of adversity, as we have seen numerous times in the past. Readers of history know that their responsibility lies here. 35

This statement does not call for much comment, as it illustrates cogently issues that have been raised above, especially the rendering of “Chinese” history into a sui generis narrative of development where “outside forces” appear not as contributors to but “disturbances” in the region’s development, and imperial conquests of “the frontiers” a beneficent absorbtion into a history that was always “Chinese.” Ironically, while Marxist historiography in the 1930s(and until its repudiation for all practical purposes in the 1980s) condemned most of this past as “feudal,” it also provided “scientific” support to its autonomous unfolding through “modes of production” that of necessity followed the internal dialectics of development. 36

A noteworthy question raised by this statement concerns the translation’s use of “China,” presumably for Zhongguo in the original, which returns us to the perennial question of naming in our disciplinary practices. How to name the new “comprehensive histories” was an issue raised by Liang Qichao from the beginning. In a section of his essay, “Discussion of Zhongguo History,” entitled “Naming Zhongguo History,” he wrote,

Of all the things I am ashamed of, none equals my country not having a name. It is commonly called ZhuXia[all the Xia], or Han people, or Tang people, which are all names of dynasties. Foreigners call it Zhendan[Khitan] or Zhina[Japanese for China], which are names that we have not named. If we use Xia, Han or Tang to name our history, it will pervert the goal of respect for the guomin[citizens]. If we use Zhendan, Zhina, etc., it is to lose our name to follow the master’s universal law [gongli]. Calling it Zhongguo or Zhonghua is pretentious in its exaggerated self-esteem and self-importance. ; it will draw the ridicule of others. To name it after a dynasty that bears the name of one family is to defile our guomin. It cannot be done. To use foreigners’ suppositions is to insult our guomin. That is even worse. None of the three options is satisfactory. We might as well use what has become customary. It may sound arrogant, but respect for one’s country is the way of the contemporary world. 37

Liang was far more open-minded than many of his contemporaries and intellectual successors. Interestingly, he also proposed a three-fold periodization of Zhongguo history into Zhongguo’s Zhongguo from the “beginning of history” with the Yellow Emperor(he consigned the period before that to “prehistory”) to the beginning of the imperial period, when Zhongguo had developed in isolation; Asia’s Zhongguo(Yazhou zhu Zhongguo)from the Qin and Han Dynasties to the Qianlong period of the Qing, when Zhongguo had developed as part of Asia; and, since the eighteenth century, the world’s Zhongguo(shijie zhi Zhongguo), when Zhongguo had become part of the world. 38

Historicizing “China/Zhongguo

Historicizing terms like China/Zhongguo or Chinese/Zhongguo ren is most important for disrupting their naturalization in nationalist narratives of national becoming. It is necessary, as Leo Shin has suggested, “to not take for granted the `Chineseness’ of China,” and to ask: “how China became Chinese.” 39 It is equally important, we might add, to ask how and when Zhong guo became Zhongguo, to be re-imagined under the sign of “China.”

Strictly speaking by the terms of their reasoning, Zhongguo/China as conceived by late Qing thinkers named the nation-form with which they wished to replace the imperial regime that seemed to have exhausted its historical relevance. The new nation demanded a new history for its substantiation. Containing in a singular continuous Zhongguo history the many pasts that had known themselves with other names was the point of departure for a process Edward Wang has described pithily as “inventing China through history.” 40 The schemes proposed for writing the new idea of Zhongguo into the past by the likes of Liang Qichao, Zhang Taiyan or Xia Zengyou (author of the first “new” history textbook in three volumes published in 1904-1906) drew upon the same evolutionary logic that guided the already available histories of “China” by Japanese and Western historians, re-tailoring them to satisfy the explicitly acknowledged goal of fostering national consciousness. In these “narratives of unfolding,” in Melissa Brown’s felicitous phrase, the task of history was no longer to chronicle the “transmission of the Way”(Daotong), as it had been in Confucian political hagiography, but to bear witness to struggles to achieve the national idea that was already implicit at the origins of historical time. 41 The break with the intellectual premises of native historiography was as radical as the repudiation of the imperial regime in the name of the nation-form that rested its claims to legitimacy not on its consistency with the Way or Heaven’s Will but on the will of the people who constituted it, no longer as mere subjects but as “citizens”(guomin) with a political voice. From the very beginning, “citizenship” was the attribute centrally if not exclusively of the majority ethnic group that long had self-identified as Han, Hua, or HuaXia—for all practical purposes, the “Chinese” of foreigners. Endowed with the cultural homogeneity, longevity and resilience that also were the desired attributes of Zhongguo, this group has served as the defining center of Zhongguo history, as it has of “Chinese” history in foreign contexts

In a discussion celebrated for its democratic approach to the nation, “What is a Nation?,” the French philosopher Ernst Renan observed that,

Forgetting, I would even say historical error, is an essential factor in the creation of a nation and it is for this reason that the progress of historical studies often poses a threat to nationality. Historical inquiry, in effect, throws light on the violent acts that have taken place at the origin of all political formation, even those that have been the most benevolent in their consequences. 42

The quest for a national history set in motion in the late Qing has likewise been beset by the same struggles over memory and forgetting that have attended the invention of nations in the modern world. Similarly as elsewhere, the same forces that spawned the search for a nation and a national history transformed intellectual life with the introduction of professional disciplines, among them, history. 43 The imperial Confucian elite that had monopolized both official and non-official historical writing had developed sophisticated techniques of empirical inquiry and criticism which found their way into the new historiography. But the new historians answered to different notions and criteria of “truth” which at least potentially and frequently in actuality made their work “a threat to nationality.” From the very beginning, moreover, historians were divided over conceptions of the nation, its constitution and its ends. These divisions were manifest by the late thirties in conflicts over the interpretation of the national past among conservatives, liberals and Marxists, to name the most prominent, all of whom also had an ambivalent if not hostile relationship to official or officially sanctioned histories. 44

What was no longer questioned, however, was the notion of Zhongguo history, which by then already provided the common ground for historical thinking and inquiry, regardless of the fact that the most fundamental contradictions that drove historical inquiry were products of the effort to distill from the past a national history that could contain its complexities. Laurence Schneider has astutely captured by the phrase, “great ecumene,” the notion of Tianxia (literally, Under-Heaven) which in its Sinocentric version has commonly been rendered into a “Chinese world-order.” 45 If Tianxia had a center, it was Zhong guo as Central State, not Zhongguo as “China.” Zhongguo/China history not only has erased(or marginalized) the part others played in the making of this ecumene(and of the Central State itself), but also has thrown the alluring cover of benevolent “assimilation” upon successive imperial states that controlled much of the space defined by the ecumene not by virtuous gravitation but by material reward and colonial conquest—including the area contained by the Great Wall, so-called “China proper.” It is rarely questioned if neighboring states that modeled themselves after the Central State did so not out of a desire to emulate the superior “Chinese” culture but because of its administrative sophistication and roots in venerated Zhou Dynasty classics—or, indeed, when Confucius became “Chinese”—especially as these states were quite wary of the imperialism of the Central State and on occasion at war with it. It is commonly acknowledged by critics and defenders alike, moreover, that the various societies that made up the “great ecumene” at different times were governed by different principles internally and externally than those that govern modern nations. The Han/Hua conquest of “China proper” no doubt brought about a good measure of cultural commonality among the people at large and uniformity for the ruling classes, but it did not erase local cultures which have persisted in intra-ethnic differences among the Han. Even more significantly from a contemporary perspective, so-called tributary states and even colonized areas such as Tibet and Xinjiang were independent parts of an imperial tribute system rather than “inherent” properties of a Zhongguo/Chinese nation. Nationalist historiography has not entirely erased these differences which are recognized in such terms as “five races in unity”(wuzu gonghe) under the Guomindang government in the 1930s, and “many origins one body”(duoyuan yiti), that is favored by its Communist successors. But these gestures toward multi-culturalism has not stopped successive nationalist governments(or the histories they have sponsored) from claiming Tianxia as their own, or even extending their proprietary claims into the surrounding seas. In Ruth Hung’s incisive expression, “Sino-orientalism thrives on the country’s expansionism and success on the global stage. It is about present-day China in relation to the world, and in relation to itself—to its past and to its neighbouring peoples in particular. Its critique of external orientalism conceals and masquerades a nationalism; it is an alibi for nationalism and empire.” 46

Critical historians have not hesitated to question these claims. The prominent historian Gu jiegang, known for his “doubting antiquity”(yigu) approach to the past, wrote in 1936, in response to officially sponsored claims that Mongols, Manchus, Tibetans, Muslims, etc., were all descended from the Yellow Emperor and his mythical cohorts, that “If lies are used, what is to keep our people from breaking apart when they discover the truth? Our racial self-confidence must be based on reason. We must break off every kind of unnatural bond and unite on the basis of reality.” 47 His warning was well placed. The contradictions generated by Zhongguo/China history continue to defy conservative nationalist efforts to suppress or contain them. Such efforts range from claims to exceptionalism to, at their most virulent, xenophobic fears of contamination by outside forces, usually “the West.” 48 Interestingly, attacks on pernicious “Western” influences betray little recognition of the “Western” origins of the idea of “Zhongguo” they seek to enforce.

The Politics of Names

Knowing the origins of Zhongguo in its translingual relationship to “China” is not likely to make any more difference in scholarly discourse or everyday communication than knowing that words like “China” or “Chinese” are reductionist mis-representations that reify complex historical relationships. It may be unreasonable to expect that they be placed in quotation marks in writing to indicate their ambiguity, and even less reasonable to qualify their use in everyday speech with irksome gestures of quotation. It should be apparent from the Chinese language names I have used above , however, I believe that we should be able to use a wider range of vocabulary in Chinese even in popular communication to enrich our store of names for the country and for the people related to it one way or another.

Is the concern with names otherwise no more than an esoteric academic exercise? I think not. Three examples should suffice here to illustrate the political significance of naming. First is the case of Taiwan where proponents of independence insist on the necessity of a Taiwan history distinct from Zhongguo history, justified by a deconstruction of Zhongguo history that opens up space for differences in trajectories of historical development for different “Chinese” societies, including on the Mainland itself. 49 In the case of Taiwan, these differences were due above all to the presence of an indigenous population before the arrival of the Han, and the colonial experience under Japan, that are considered crucial to the development of a local Taiwanese culture. 50 The colonial experience as a source of historical and cultural difference has also been raised as an issue in recent calls for a Hong Kong history, along with calls for independence. Such calls derive plausibility from proliferating evidence of conflict between local populations in “Chinese” societies such as Hong and Singapore and more recent arrivals from the PRC. 51

The second example pertains to the seas that are the sites of ongoing contention between the PRC and its various neighbors. In the PRC maps that I am familiar with, these seas are still depicted by traditional directional markers as Southern and Eastern Seas. Their foreign names, South China Sea and East China Sea are once again reminders of the part Europeans played in mapping and naming the region, as they did the world at large, with no end of trouble for indigenous inhabitants. The names bring with them suggestions of possession that no doubt create some puzzlement in public opinion if not bias in favor of PRC claims. They also enter diplomatic discourses. In the early 1990s, “ASEAN states called for a name change of the South China Sea to eliminate `any connotation of Chinese ownership over that body of water.’” 52The Indian author of a news article dated 2012, published interestingly in a PRC official publication, Global Times, writes that, “While China has been arguing that, despite the name, the Indian Ocean does not belong to India alone, India and other countries can equally contend that South China Sea too does not belong to China alone.” 53 A recent petition sponsored by a Vietnamese foundation located in Irvine California, addressed to Southeast Asian heads of state, proposes that the South China Sea be renamed the Southeast Asian Sea, a practice I myself have been following for over a year now. 54 In a related change not directly pertinent to the PRC, Korean-Americans in the state of Virginia recently pressured the state government successfully to add the Korean name, “East Sea” in school textbook maps alongside what hitherto had been the “Sea of Japan.”

Names obviously matter, as do maps, not only defining identities but also their claims on time and space. Histories of colonialism offer ample evidence that mapping and naming was part and parcel of colonization. It is no coincidence that de-colonization has been accompanied in many cases by the restoration of pre-colonial names to maps. Maps are a different matter, as they also have come to serve the nation-states that replaced colonies, again with no end of trouble in irredentist or secessionist claims.

My third example is the idea of “China” itself, the subject of this essay. The reification of “China” finds expression in an ahistorical historicism: the use of history in support of spatial and temporal claims of dubious historicity, projecting upon the remote past possession of territorial spaces that became part of the empire only under the last dynasty, and under a very different notion of sovereignty than that which informs the nation–state. It was the Ming(1368-1644) and Qing(1644-1911) dynasties, following Yuan(Mongol) consolidation, that created the coherent and centralized bureaucratic despotism that we have come to know as “China.” These dynasties together lasted for a remarkable six centuries(roughly the same as the Ottoman Empire in Western Asia), in contrast to the more than twenty fragmented polities(some of equal duration, like the Han and the Tang) that succeeded one another during the preceding 1500 years of imperial rule. The relatively stable unity achieved under the consolidated bureaucratic monarchy of the last six centuries has cast its shadow over the entire history of the region which up until the Mongol Yuan Dynasty(1275-1368) had witnessed ongoing political fluctuation between dynastic unity and “a multistate polycentric system.” 55

In his study of Qing expansion into Central Asia, James Millward asks the reader to “think of the different answers a scholar in the late Ming and an educated Chinese at the end of the twentieth century would give to the questions, `Where is China?’ and `Who are the Chinese?’ and goes on to answer:

We can readily guess how each would respond: The Ming scholar would most likely exclude the lands and peoples of Inner Asia, and today’s Chinese include them(along with Taiwan, Hong Kong, and perhaps even overseas Chinese communities). These replies mark either end of the process that has created the

ethnically and geographically diverse China of today. 56

In light of the discussion above, Millward goes only part of the distance. Unless he was a close associate of the Jesuits, the late Ming scholar would most likely have scratched his head, as did Pereira’s subjects, wondering what “China” might be. Even so, the question raised by Qing historians like Millward, who advocate “Qing-centered” rather than “China-centered” histories, have prompted some conservative PRC historians to charge them with a “new imperialism” that seeks “to split” China—a favorite charge brought against minorities that seek some measure of autonomy, or those in Hong Kong and Taiwan who would rather be Hong Kong’ers and Taiwanese rather than “Chinese.” 57

Such jingoistic sentiments aside, it is a matter of historical record that it was Manchu rulers of the Qing that annexed to the empire during the eighteenth century approximately half of the territory the PRC commands presently—from Tibet to Xinjiang, Mongolia , Manchuria and Taiwan, as well as territories occupied by various indigenous groups in the Southwest. Until they were incorporated into the administrative structure in the late nineteenth century, moreover, these territories were “tributary” fiefdoms of the emperor rather than “inherent”(guyoude) possessions of a “Chinese” nation, as official historiography would claim. Complex histories are dissolved into a so-called “5000-year Chinese history” which has come to serve as the basis for both irredentist claims and imperial suppression of any hint of secessionism on the part of subject peoples. The PRC today is plagued by ethnic insurgency internally, and boundary disputes with almost all of its neighboring states. It may not bear sole responsibility for these conflicts as these neighboring states in similar fashion project their national claims upon the past. Suffice it to say here that “Zhongguo/China,” which represented a revolutionary break with the past to its formulators in the early twentieth century, has become a prisoner of the very myths that sustain it. Ahistorical historicism is characteristic of all nationalism. “Zhongguo/China” is no exception.

There are no signs indicating any desire to re-name the country after one of the ancient names that are frequently invoked these days in gestures to “tradition,” names like Shenzhou, Jiuzhou, etc. Those names in their origins referred to much more limited territorial spaces, shared with others, even if they were adjusted over subsequent centuries to accommodate the shifting boundaries of empire. Zhongguo/China, as putative heir to two-thousand years of empire, claims for the nation imperial territories as well as the surrounding seas at their greatest extent (which was reached, not so incidentally, under the Mongols and Manchus), and at least in imagination relocates them at the origins of historical time. The cosmological order of “all-under-heaven” (tianxia), with the emperor at its center(Zhongguo) has been rendered into a Chinese tianxia. Its re-centering in the nation rules out any conceptualization of it as a shared space in favor of an imperium over which the nation is entitled to preside, which hardly lends credence to assertions by some PRC scholars and others of significant difference from modern imperialism in general. 58 An imperial search for global power is also evident in the effort to remake into “Chinese” silk roads the overland and maritime silk roads constructed over the centuries out of the relay of people and commodities across the breadth of Asia.

Names do matter. They also change. I will conclude here by recalling the prophetic words of the Jesuit Matteo Ricci as he encountered “China” in the late sixteenth century: “The Chinese themselves in the past have given many different names to their country and perhaps will impose others in the future.” Who knows what the future may yet bring?

* I would like to express my appreciation to David Bartel, Yige Dong, Harry Harootunian, Ruth Hung, John Lagerwey, Kam Louie, Mia Liu, Sheldon Lu, Roxann Prazniak, Tim Summers, QS Tong, Rob Wilson and anonymous readers for boundary 2 for their comments and suggestions on this essay. They are not responsible for the views I express.

notes:

1. Claims to exceptionalism may be characteristic of all nationalism, as a defining feature in particular of right-wing nationalism. There is nothing exceptional about Chinese claims to exceptionality, except perhaps its endorsement by others. The United States is, of course, the other prominent example. The two “exceptionalisms” were captured eloquently in one of the earliest encounters between the two polities when the US Minister Anson Burlingame in 1868 proclaimed the prospect of “the two oldest and youngest nations” in the world marching together hand-in-hand into the future. Exceptionalism, we may note, easily degenerates into an excuse for assumptions of cultural superiority and imperialism. Under pressure from conservatives, Boards of Education in Texas and Colorado have recently enjoined textbook publishers to stress US exceptionalism in school textbooks. The drift to the right has also been discernible in the PRC since Xi Jingping has assumed the presidency and encouraged attacks on scholars who in the eyes of Party conservatives have been “brain-washed” by “Western” influence. For a report on US textbook controversies, see, Sara Ganim, “Making history: Battles brew over alleged bias in Advanced Placement standards,” CNN, February 24, 2015, http://www.cnn.com/2015/02/20/us/ ap-history-framework-fight/ (consulted 8 March 2015). To their credit, students in Colorado and Hong Kong high-schools have walked out of classes in protest of so-called “patriotic education,” an option that is not available to the students in the PRC—even if they were aware of the biases in their school textbooks.

Back to essay

2. Some recent examples are, Lydia H. Liu, The Clash of Empires: The Invention of China in Modern World Making (Cambrdge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004); Wang Gungwu, China and the Chinese Overseas(Singapore: Academic Press, 1992); Leo Shin, The Making of the Chinese State: Ethnicity and Expansion on the Ming Borderlands(New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006) ; Zhao Gang, “Reinventing China: Imperial Ideology and the Rise of Modern Chinese National Identity in the Early Twentieth Century,” Modern China 32.1(January 2006): 3-30; Joseph W. Esherick, “How the Qing Became China, in Joseph W. Esherick, Hasan Kayali, and Eric Van Young (ed), Empire to Nation: Historical Perspectives on the Making of the Modern World (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2006), pp. 229-259; Arif Dirlik, “Timespace, Social Space and the Question of Chinese Culture,” in Dirlik, Culture and History in Postrevolutionary China(Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 2011), pp. 157-196; Arif Dirlik, “Literary Identity/Cultural Identity: Being Chinese in the Contemporary World,” Modern Chinese Literature and Culture(MCLC Resource Center Publication, 2013) ; Peter K. Bol, “Middle-period discourse on the Zhong guo: The central country,” Hanxue yanjiu(2009), http://nrs. harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos: 3629313; Melissa J. Brown, Is Taiwan Chinese? The Impact of Culture, Power, and Migration on Changing Identities(Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2004); Hsieh Hua-yuan, Tai Pao-ts’un and Chou Mei-li, Taiwan pu shih Chung-kuo te: Taiwan kuo-min te li-shih(Taiwan is not Zhongguo’s: A history of Taiwanese citizens)(Taipei: Ts’ai-t’uan fa-jen ch’un-ts’e hui, 2005) ; Lin Jianliang, “The Taiwanese are Not Han Chinese,” Society for the Dissemination of Historical Fact, 6/6/2015, http://www.sdh-fact.com/essay-article/418 ; Shi Aidong, Zhongguo longde faming: : shijide long zhengzhi yu Zhongguo xingxiang (The Invention of the Chinese Dragon: Dragon Politics during the 16-20th centuries and the Image of China)(Beijing: Joint Publishing Company, 2014); Ge Zhaozhuang, Zhai zi Zhong guo: zhongjian youguan `Zhong guo’de lishi lunshu (Dwelling in this Zhongguo: Re-narrating the History of `Zhongguo’)(Beijing: Zhonghua Publishers, 2011); Ge Zhaozhuang, He wei Zhongguo: jiangyu, minzu, wenhua yu lishi(What is Zhongguo: Frontiers, Nationalities, Culture and History)(Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 2014); Ren Jifang, “`HuaXia’ kaoyuan” (On the Origins of “HuaXia,” in Chuantong wenhua yu xiandaihua(Traditional Culture and Modernization), #4(1998). For an important early study, see, Wang Ermin, “`Chung-kuo ming-cheng su-yuan chi ch’I chin-tai ch’uan-shih”(The Origins of the name “Chung-kuo” and Its Modern Interpretations), in Wang Ermin, Chung-kuo chin-tai si-hsiang shih lun((Essays on Modern Chinese Thought)(Taipei: Hushi Publishers, 1982), pp. 441-480. The bibliographies of all these works refer to a much broader range of studies. Prasenjit Duara has offered an extended critique of nationalism in history writing with reference to the twentieth-century in, Rescuing History from the Nation: Questioning Narratives of Modern China (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1997). I am grateful to Leo Douw for bringing Ge(2014) to my attention, and Stephen Chu for helping me acquire it at short notice..

Back to the essay

3. I am referring here to the important argument put forward by Lionel Jensen, Manufacturing Confucianism: Chinese Traditions and Universal Civilization(Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998) that Jesuits “manufactured” Confucianism as the cultural essence of “China” which was equally a product of their manufacture. For the confusion of names in both Chinese and European languages that confronted the Jesuits, see, Matteo Ricci/Nicholas Trigault, China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Matteo Ricci, 1583-1610, tr. from the Latin by Louis Gallagher, S.J.(New York: Random House, 1953), pp.6-7. Ricci/Trigault write prophetically that “The Chinese themselves in the past have given many different names to their country and perhaps will impose others in the future.”(p. 6). The Jesuits also undertook a mission to make sure that the name popularized by Marco Polo, Cathay, was the same as “China.” Pp.312-313, 500-501

Back to the essay

4. The term minzu absorbs ethnicity into “nationality.” From that perspective, there could be no intra-Han ethnicity. See, Melissa Brown, , Is Taiwan Chinese?, and Emily Honig, Creating Chinese Ethnicity: Subei People in Shanghai, 1580-1980(New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1992)

Back to the essay

5. The racist homogenization of the Han (not to speak of “Chinese”) population is contradicted by studies of genetic variation. There is still much uncertainty about these studies, but not about the heterogeneity of the population which, interestingly, has been found to correspond to regional and linguistic variation: “Interestingly, the study found that genetic divergence among the Han Chinese was closely linked with the geographical map of China. When comparisons were made an individual’s genome tended to cluster with others from the same province, and in one particular province, Guangdong, it was even found that genetic variation was correlated with language dialect group. Both of these findings suggest the persistence of local co-ancestry in the country. When looking at the bigger picture the GIS scientists noticed there was no significant genetic variation when looking across China from east to west, but identified a ‘gradient’ of genetic patterns that varied from south to north, which is consistent with the Han Chinese’s historical migration pattern. The findings from the study also suggested that Han Chinese individuals in Singapore are generally more closely related to people from Southern China, whilst people from Japan were more closely related with those from Northern China. Unsurprisingly, individuals from Beijing and Shanghai had a wide range of ‘north-south’ genetic patterns, reflecting the modern phenomenon of migration away from rural provinces to cities in order to find employment. “ Dr. Will Fletcher, “Thousands of genomes sequences to map Han Chinese genetic variation,” Bionews, 596(30 November 2009), http://www.bionews.org.uk/ page_51682.asp(consulted 5 December 2014). For a discussion of racism directed at minority populations, see, Gray Tuttle, “China’s Race Problem: How Beijing Represses Minorities,” Foreign Affairs, 4/22/2015, http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/143330/gray-tuttle/chinas-race-problem 1/

Back to the essay

6. It is noteworthy that the reification of “China” has a parallel in the use of “the West” (xifang) by both Chinese and Euro/Americans, which similarly ignores all the complexities of that term, including its very location. The commonly encountered juxtaposition, China/West( Zhongguo/ xifang), is often deployed in comparisons that are quite misleading in their obliviousness to the temporalities and spatialities indicated by either term.

Back to the essay

7. Liu, The Clash of Empires, p. 80. Endymion Wilkinson tells us that there were more than a dozen ways of referring to “what we now call `China.’” For a discussion of some of the names and their origins, including “China,” see, Endymion Wilkinson, Chinese History: A Manual, revised and enlarged edition(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2000), p. 132

Back to the essay

8. Victor Mair, “The North(western) Peoples and the Recurrent Origins of the `Chinese’ State,” in Joshua A. Fogel(ed), The Teleology of the Nation-State: Japan and China(Philadelphia, PA: The University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 46-84

Back to the essay

9. Bol, “Middle-Period Discourse on the Zhong Guo,” p.2. John W. Dardess, “Did the Mongols Matter? Territory, Power, and the Intelligentsiain China from the Northern Song to the Early Ming,” in Paul Jakov Smith and Richard von Glahn(ed), The Song-Yuan-Ming Transition in Chinese History(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), pp. 111-134, especially, pp. 112-122, `Political Geography: What was “China.”’ Ge Zhaoguang and Zhao Gang have also found evidence of broader uses of Zhong Guo. Ge is particularly insistent on the existence of Zhongguo from the late Zhou to the present, with something akin to consciousness of “nationhood”(ziguo, literally self-state) emerging from the seventeenth century not only in Zhongguo(under the Qing) but also in neighboring Japan and Korea. The consequence was a shift from Under-Heaven(tianxia) consciousness to something resembling an interstate system (guoji zhixu). Ge, He wei Zhongguo?, p.9. Ge’s argument is sustained ultimately by Zhongguo exceptionalism that defies “Western” categories. At the latest from the Song Dynasty, he writes, “this Zhongguo had the characteristics of `the traditional imperial state,’ but also came close to the idea of `the modern nation-state.”(p. 25). That China is not an ordinary “nation” but a “civilization-state” is popular with sympathetic prognostications of its “rise,” such as, Martin Jacques, When China Rules the World: The End of the Western World and the Birth of a New Global Order(London: Penguin Books, 2012, Second edition) and chauvinistic apologetics like Zhang weiwei, The China Wave: Rise of a Civilizational State(Hackensack, NJ: World Century Publishing Corporation, 2012). Highly problematic in ignoring the racialized nationalism that drives domestic and international policy, such arguments at their worst mystify PRC imperial expansionism. There are, of course, responsible dissenting historians who risk their careers to call the “Party line” into question. For one example, Ge Jianxiong of Fudan University, see, Venkatesan Vembu, “Tibet wasn’t ours, says Chinese scholar,” Daily News & Analysis, 22 February 2007, http://www.dnaindia.com/world/report-tibet-wasn-t-ours-says-chinese-scholar-1081523

Back to the essay

10. Henry H. Em, The Great Enterprise: Sovereignty and Historiography in Modern Korea (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013), pp. 28-29.

Back to the essay

11. Alexander Woodside, Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Nguyen and Ching Civil Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971).

Back to the essay

12. Liu, The Clash of Empires, p. 77

Back to the essay

13. Bol, “Middle-Period Discourse on the Zhong Guo,” p.4. See, also, Hsieh, Tai and Chou, Taiwan pu shih Chung-kuo te, op.cit., p.31 We might add that the celebrated “sinocentrism” of “Chinese,” based on this vocabulary, is a mirror image of “Eurocentrism” that has been internalized in native discourses.

Back to the essay

14. European(including Russian) Orientalist scholarship provided important resources in the formulation of national historical identity in other states, e.g., Turkey. For a seminal theoretical discussion, with reference to India, see, Partha Chatterjee, Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World: A Derivative Discourse? (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1986). With respect to the importance of global politics in the conception of “China,” we might recall here the Shanghai Communique (1972) issued by the US and the PRC. The Communique overnight shifted the “real China” from the Republic of China on Taiwan to the PRC.

Back to the essay

15. Shi, Zhongguo longde faming, pp. 8-9. For the original reference in Pereira, see, “The Report of Galeote Pereira,” in South China in the Sixteenth Century: Being the narratives of Galeote Pereira, Fr. Gaspar de Cruz, O.P., Fr. Martin de Rada, O.E.S.A., ed. By C.R. Boxer(London: The Hakluyt Society, Second series, #106, 1953), pp. 3-43, pp.28-29. Da Ming and Da Ming ren appear in the text as Tamen and Tamenjins. Interestingly, the account by de Rada in the same volume states that “The natives of these islands[the Philippines] call China `Sangley’, and the Chinese merchants themselves call it Tunsua, however its proper name these days is Taibin.” (p. 260). According to the note by the editor, Tunsua and Taibin are respectively Zhong hua and Da Ming from the Amoy(Xiamen) Tiong-hoa and Tai-bin. Shi recognizes that “the invention of the Chinese dragon” presupposed “the invention of China,” which is also the title of a study by Catalan scholar, Olle Manel, La Invencion de China:Perceciones et estrategias filipinas respecto China durante el siglo XVI(The Invention of China: Phillipine China Perceptions and Strategies during the 16th Century) (Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Publishers, 2000). Jonathan Spence credits Pereira with having introduced lasting themes into Euopean Images of China. Spence, The Chan’s Great Continent: China in Western Minds(New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1998), pp. 20-24. In a similar vein to Pereira’s, Matteo Ricci wrote at the end of the century, “It does not appears strange to us that the Chinese should never have heard of the variety of names given to their country by outsidersand that they should be entirely unaware of their existence.” Ricci/Trigault, China in the Sixteenth Century, p. 6

Back to the essay

16. Zhang Deyi, Suishi Faguo ji(Random Notes on France)(Hunan: Renmin chuban she, 1982), p. 182.

Back to the essay

17. Quoted in Wang Ermin, “`Chung-kuo min-gcheng su-yuan chi ch’i chin-tai ch’uan-shih,” p. 451.

Back to the essay

18. Quoted in John Fitzgerald, Awakening China: Politics, Culture, and Class in the Nationalist Revolution(Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996), p. 117.

Back to the essay

19. For a discussion of problems in the reception of Jesuit maps by Ming/Qing cartographers, see, Cordell D.K. Yee, “Traditional Chinese Cartography and the Myth of Westernization,” in J.B. Harley and David Woodward(ed), The History of Cartography, Volume 2, Book 2: Cartography in the Traditional East and Southeast Asian Societies(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), pp. 170-202.

Back to the essay

20. This term, literally “unified under one rule,” was the term Mongols used, when the Yuan Dynasty unified the realm that had been divided for nearly two centuries between the Song, Liao, Jin and Xi Xia. Brook explains that the Ming took over the term to claim “identical achievement for themselves.” See, Timothy Brook, Mr. Selden’s Map of China: Decoding the Secrets of a Vanished Cartographer(New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2013), p. 134. For a close analysis of this period, see, Morris Rossabi, China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th-14th Centuries (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983).

Back to the essay

21. Various versions of the map are available at https://www.google.com/search?q=matteo+ricci+ world+map&safe=off&biw=1113&bih=637&site=webhp&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ei=LmL2VKjWJ5C1ogSroII4&ved=0CB0QsAQ&dpr=1 .

Back to the essay

22. For Ricci’s own account of the production of the map, and the different hands it passed through, see, Ricci/Trigault, China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Matteo Ricci, 1583-1610, tr. from the Latin by Louis Gallagher, S.J.(New York: Random House, 1953), pp. 168, 331.

Back to the essay

23. Ann Heirman, Paolode Troia and Jan Parmentier, “Francesco Sambiai, A Missing Ling in European Map Making in China?,” Imago Mundi, Vol. 61, Part I(2009): 29-46, p. 39. It is quite significant that Aleni’s map, first published in 1623 toward the end of the Ming, was widely available during the Qing, and found its way into the Imperial Encyclopedia compiled under the Qianlong Emperor in the late eighteenth century..

Back to the essay

24. In this sense, the Qing case is a classical example of the Giddens-Robertson thesis that the international order preceeded, and is a condition for, the formation of the nation-state, especially but not exclusively in non-Euro/American societies. Roland Robertson, Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture(Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1994).

Back to the essay

25. It may be worth mentioning here that in spite of this equivalence, the English term is much more reductionist, and, therefore, abstract. Chinese has a multiplicity of terms for “China”: Zhongguo, Zhonghua, Xia, Huaxia, Han, Tang, etc. The term “Chinese” is even more confusing, as it refers at once to a people, to a “race,” to members of a state that goes by the name of China as well as the majority Han people who claim real Chineseness, creating a contradiction with the multiethnic state. Once again, Chinese offers a greater variety, from huaren, huamin, huayi, Tangren, Hanzu, to Zhongguoren, etc.

Back to the essay

26. Liu, The Clash of Empires. p. 126.

Back to the essay

27. Chen Hansheng(ed), Huagong chuguo shiliao huibian(Collection of Historical Materials on Hua Workers Abroad)(Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1984), 10 Volumes, Vol. 3, p.1015

Back to the essay

28. “Zongli yamen fu zhuHua Meishi qing dui Bilu Huagong yu yi yuanshou han”(Zongli yamen Letter to the American Ambassador’s Request for Help to Chinese Workers in Peru)(18 April 1869). In Ibid., p.966. The Zongli Yamen(literally the general office for managing relations with other countries), established as part of the Tongzhi Reforms of the 1860s, served as the Qing Foreign Office until the governmental reorganization after 1908.

Back to the essay

29. “Zongli yamen wei wuyue guo buxu zai Hua sheju zhaogong bing bujun Huaren qianwang Aomen gei Ying, Fa, E, Mei Ri guo zhaaohui”(Zongli yamen on the Prohibition of Labor Recruitment by Non-Treaty Countries and on Chinese Subjects Communicating with England, France, Russia, United States and Japan in Macao.” In Ibid., pp.968-969, p. 968.

Back to the essay

30. Wang Ermin, pp. 452, 456.

Back to the essay

31. Chen Yuzheng, Zhonghua minzu ningjuli de lishi tansuo(Historical Exploration of the Chinese Nation’s Power to Come Together)(Kunming: Yunnan People’s Publishing House, 1994). See Chapter 4, “Zhongguo—cong diyu he wenhua gainian dao guojia” mingcheng” (Zhongguo: from region and culture concept to national name), pp. 96-97.

Back to the essay

32. For history, geography and archeology, in the late Qing and early Republic, see the essays by Peter Zarrow, Tzeki Hon and James Leibold in Brian Moloughney and Peter Zarrow(ed), Transforming History: The Making of a Modern Academic Discipline in Twentieth-century China (Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 2011). See also, Chen Baoyun, Xueshu yu guojia: “Shidi xuebao” ji qi xue renqun yanjiu(Scholarship and the State: The History and Geography Journal and Its Studies of Social Groupings)(Hefei, Anhui: Anhui Educational Press, 2008). For ethnology and sociology, see, Wang Jianmin, Zhongguo minzuxue shi(History of Chinese Ethnology), Vol. I(Kunming: Yunnan Educational Publishers, 1997), and, Arif Dirlik(ed), Sociology and Anthropology in Twentieth-Century China: Between Universalism and Indigenism (Hong Kong: Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 2012). See, also, Q. Edward Wang, Inventing China Through History: The May Fourth Approach to Historiography(Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2001); James Leibold, “Competing Narratives of National Unity in Republican China: From the Yellow Emperor to Peking Man,” Modern China, 32.2(April 2006): 181-220; and, Tze-ki Hon, “Educating the Citizens: Visions of China in Late Qing History Textbooks” (published in The Politics of Historical Production in Late Qing and Republican China [Brill, 2007], 79-105) (35 pages). . A recent study provides a comprehensive account of the transformation of historical consciousness, practice and education during this period through the growth of journalism. See, Liu Lanxiao, Wan Qing baokan yu jindai shixue(late Qing Newspapers and Journals and Modern Historiography)(Beijing: People’s University, 2007).

Back to the essay

33. For further discussion, see, Dirlik, “Timespace, Social Space and the Question of Chinese Culture,” pp. 173-180. Shi Aidong’s study of “the invention of the Chinese dragon” offers an amusing illustration of how the dragon, rendered into a symbol of “China” by Westerners, has been appropriated into the Chinese self-image extended back to the origins of “Chinese” civilization. It is not that the dragon figure did not exist in the past, but that a symbol that had been reserved exclusively or the emperor (and aspirants to that status) has been made into the symbol of the nation.

Back to the essay

34. Zhao Meichun, Ershi shiji Zhongguo tongshi bianzuan yanjiu(Research into the Compilation of Comprehensive Histories in Twentieth-century China)(Beijing: Chinese Social Science Publications Press, 2007).

Back to the essay

35. Quoted(as an epigraph) in Peter Zarrow, “Discipline and Narrative: Chinese History Textbooks in the Early Twentieth Century, in Moloughney and Zarrow(ed), Transforming History, pp. 169-207, p. 169. We may note that the notion of “China” going back to legendary emperors resonated with orientalist notions of “China” as a timeless civilization. It is inscribed in the appendices of most dictionaries, which means it reaches most people interested in “China” and “Chinese.”

Back to the essay

36. For further discussion, see, Arif Dirlik, “Marxism and Social History,” in Ibid., pp. 375-401. Marxist historiography took a strong nationalist turn during the War of Resistance Against Japan(1937-1945). The rise of “cultural nationalism” among Marxists and non-Marxists alike during this period is explored in Tian Liang, Kangzhan shiqishixue yanjiu(Historiography During the War of Resistance)(Beijing: Renmin Publishers, 2005). Possibly the most influential product of this period well into the post-1949 years was Zhongguo tongshi jianbian(A Condensed Comprehensive History of Zhongguo) sponsored by the Zhongguo Historical Research Association and compiled under the chief editorship of the prominent historian Fan Wenlan(first edition, 1947).

Back to the essay

37. Liang Qichao, “Zhongguo shi Xulun”(Discussion of Zhongguo History)(1901),” in Liang, Yinping shi wenji(Collected Essays from Ice-Drinker’s Studio), #6(Taipei: Zhonghua Shuju, 1960), 16 vols., Vol 3, pp. 1-12, p.3.

Back to the essay

38. Ibid., pp. 11-12. See, also, Xiobing Tang, Global Space and the Nationalist Discourse of Modernity: The Historical Thinking of Liang Qichao(Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996), Chap. 1.

Back to the essay

39. Shin, The Making of the Chinese State, p. xiii. As the above discussion suggests, how “China” became “China” is equally a problem.

Back to the essay

40. Q. Edward Wang, Inventing China Through History: The May Fourth Approach to Historiography(Albany, NY: The State University of New York Press, 2001).

Back to the essay

41. Brown, Is Taiwan Chinese?, pp. 28-33. For Daotong, see, Cai Fangli, Zhongguo Daotong sixiang fazhan shi(History of Zhongguo Daotong Thinking)(Chengdu: Sichuan Renmin Publishers, 2003). Cai traces the oigins of Daotong thinking to the legendary emperors, Fuxi, Shennong and Yellow Emperor, and its formal systematization and establishment to the Tang Dynasty Confucian, Han Yu, who played an important part in rolling back the influence of Buddhism and Daoism to restore Confucianism to ideological supremacy. He attributes the formulation of “Daotong historical outlook”(Daotong shi guan) to the Han Dynasty thinker, Dong Zhongshu, who formulated a cosmology based on Confucian values(p. 239). In this ourlook, dynasties changed names, but the Dao(the Way) remained constant, and dynasties rose and fell according to their grasp or loss of the Dao.

Back to the essay

42. Ernest Renan, “What is a Nation?” Text of a speech delivered at the Sorbonne on 11 March

1882, in Ernest Renan, Qu’est-ce qu’une nation?tr. by Ethan Rundell, (Paris: Presses-Pocket, 1992), p.3.

Back to the essay

43. See the essays in Moloughney and Zarrow(ed), Transforming History: The Making of a Modern Academic Discipline in Twentieth-century China.

Back to the essay

44. See, Li Huaiyin, Reinventing Modern China: Imagintion and Authenticity in Chinese Historical Writing(Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press, 2013).

Back to the essay

45. Laurence A. Schneider, Ku Chieh-kang and China’s New History: Nationalism and the Quest for Alternative Traditions(Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1971), p. 261. For further discussion of “ecumene,” see, Arif Dirlik, “Timespace, Social Space and the Question of Chinese Culture,” in Dirlik, Culture and History in Postrevolutionary China, pp. 157-196, pp. 190-196. A concise and thoughtful historical discussion of Tianxia by a foremost anthropologist is, Wang Mingming, “All Under Heaven (tianxia): cosmological perspectives and political ontologies in pre-modern China,” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 2(1): 337-383. Morris Rossabi, China Among Equals, offers a portrayal of the ecumene. It was only in the late imperial period during the Ming and the Qing Dynsties(1368-1911) that the centralized bureaucratic regime emerged that we know as “China.” For a portrayal of cosmopolitanism during the Mongol Empire, see, Thomas T. Allsen, “Ever Closer Encounters: The Appropriation of Culture and the Apportionment of Peoples During the Mongol Empire,” Journal of Early Modern History,1.1(1997): 2-23. For a critical discussion of the PRC preference for sinocentrism over “shared history” in the region, see, Gilbert Rozman, “Invocations of Chinese Traditions in International Relations,” Journal of Chinese Political Science(2012) 17: 111-124.

Back to the essay

46. Ruth Y.Y. Hung, “What Melts in the `Melting Pot’ of Hong Kong?,” Asiatic, Volume 8, Number 2(December 2014): 57-87, p. 74.

Back to the essay

47. Quoted in Schneider, Ibid..

Back to the essay

48. For a recent report on the attack on academics “scornful of China” or their deviations from official narratives, see, “China professors spied on, warned to fall in line,” CBS News, November 21, 2014, http://www.cbsnews.com/news/china-communist-newspaper-shames-professors-for-being-scornful-of-china/# (consulted 22 November 2014). It is not only official histories that promote a “5000-year glorious history.” The same mythologizing of the past may be found among the population at large, nativist historians, and opponents of the Communist regime such as the Falun gong which serves to unsuspecting spectators the very same falsehoods dressed up as Orientalist exotica. A brochure for the Falun gong “historical spectacle, Shen Yun, in Eugene, Or, states that, “Before the dawn of Western civilization, a divinely inspired culture blossomed in the East. Believed to be bestowed from the heavens, it valued virtue and enlightenment. Embark on an extraordinary journey through 5000 years of glorious Chinese heritage, where legends come alive and good always prevails. Experience the wonder of authentic Chinese culture.”

Back to the essay

49. Hsieh, Tai, and Chou, Taiwan pu shih Chung-kuo te: Taiwan kuo-min te li-shih. Former Taiwan President, and proponent of independence, Lee Teng-hui, was involved in the publication of this book. The title translates literally as “Taiwan Is Not Zhongguo’s”—in other words, does not belong to Zhongguo.

Back to the essay