a review of Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee, The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (W.W. Norton, 2014)

~

Business futurism is a grim discipline. Workers must either adapt to the new economic realities, or be replaced by software. There is a “race between education and technology,” as two of Harvard’s most liberal economists insist. Managers should replace labor with machines that require neither breaks nor sick leave. Superstar talents can win outsize rewards in the new digital economy, as they now enjoy global reach, but they will replace thousands or millions of also-rans. Whatever can be automated, will be, as competitive pressures make fairly paid labor a luxury.

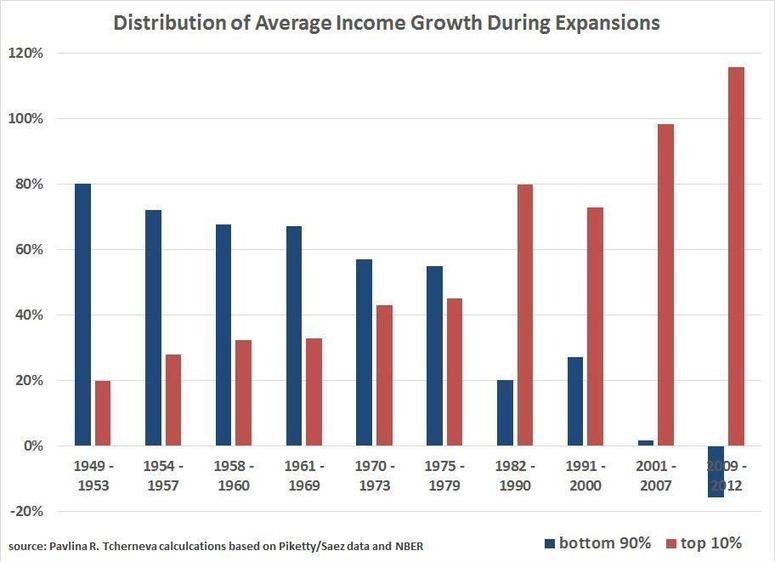

Thankfully, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee’s The Second Machine Age (2MA) downplays these zero-sum tropes. Brynjolffson & McAfee (B&M) argue that the question of distribution of the gains from automation is just as important as the competitions for dominance it accelerates. 2MA invites readers to consider how societies will decide what type of bounty from automation they want, and what is wanted first. The standard, supposedly neutral economic response (“whatever the people demand, via consumer sovereignty”) is unconvincing. As inequality accelerates, the top 5% (of income earners) do 35% of the consumption. The top 1% is responsible for an even more disproportionate share of investment. Its richest members can just as easily decide to accelerate the automation of the wealth defense industry as they can allocate money to robotic construction, transportation, or mining.

A humane agenda for automation would prioritize innovations that complement (jobs that ought to be) fulfilling vocations, and substitute machines for dangerous or degrading work. Robotic meat-cutters make sense; robot day care is something to be far more cautious about. Most importantly, retarding automation that controls, stigmatizes, and cheats innocent people, or sets up arms races with zero productive gains, should be a much bigger part of public discussions of the role of machines and software in ordering human affairs.

2MA may set the stage for such a human-centered automation agenda. Its diagnosis of the problem of rapid automation (described in Part I below) is compelling. Its normative principles (II) are eclectic and often humane. But its policy vision (III) is not up to the challenge of channeling and sequencing automation. This review offers an alternative, while acknowledging the prescience and insight of B&M’s work.

I. Automation’s Discontents

For B&M, the acceleration of automation ranks with the development of agriculture, or the industrial revolution, as one of the “big stories” of human history (10-12). They offer an account of the “bounty and spread” to come from automation. “Bounty” refers to the increasing “volume, variety, and velocity” of any imaginable service or good, thanks to its digital reproduction or simulation (via, say, 3-D printing or robots). “Spread” is “ever-bigger differences among people in economic success” that they believe to be just as much an “economic consequence” of automation as bounty.[1]

2MA briskly describes various human workers recently replaced by computers. The poor souls who once penned corporate earnings reports for newspapers? Some are now replaced by Narrative Science, which seamlessly integrates new data into ready-made templates (35). Concierges should watch out for Siri (65). Forecasters of all kinds (weather, home sales, stock prices) are being shoved aside by the verdicts of “big data” (68). “Quirky,” a startup, raised $90 million by splitting the work of making products between a “crowd” that “votes on submissions, conducts research, suggest improvements, names and brands products, and drives sales” (87), and Quirky itself, which “handles engineering, manufacturing, and distribution.” 3D printing might even disintermediate firms like Quirky (36).

In short, 2MA presents a kaleidoscope of automation realities and opportunities. B&M skillfully describe the many ways automation both increases the “size of the pie,” economically, and concentrates the resulting bounty among the talented, the lucky, and the ruthless. B&M emphasize that automation is creeping up the value chain, potentially substituting machines for workers paid better than the average.

What’s missing from the book are the new wave of conflicts that would arise if those at very top of the value chain (or, less charitably, the rent and tribute chain) were to be replaced by robots and algorithms. When BART workers went on strike, Silicon Valley worthies threatened to replace them with robots. But one could just as easily call for the venture capitalists to be replaced with algorithms. Indeed, one venture capital firm added an algorithm to its board in 2013. Travis Kalanick, the CEO of Uber, responded to a question on driver wage demands by bringing up the prospect of robotic drivers. But given Uber’s multiple legal and PR fails in 2014, a robot would probably would have done a better job running the company than Kalanick.

That’s not “crazy talk” of communistic visions along the lines of Marx’s “expropriate the expropriators,” or Chile’s failed Cybersyn.[2] Thiel Fellow and computer programming prodigy Vitaly Bukherin has stated that automation of the top management functions at firms like Uber and AirBnB would be “trivially easy.”[3] Automating the automators may sound like a fantasy, but it is a natural outgrowth of mantras (e.g., “maximize shareholder value”) that are commonplaces among the corporate elite. To attract and retain the support of investors, a firm must obtain certain results, and the short-run paths to attaining them (such as cutting wages, or financial engineering) are increasingly narrow. And in today’s investment environment of rampant short-termism, the short is often the only term there is.

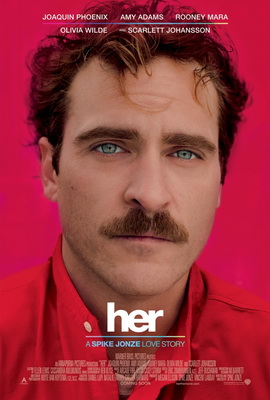

In the long run, a secure firm can tolerate experiments. Little wonder, then, that the largest firm at the cutting edge of automation—Google—has a secure near-monopoly in search advertising in numerous markets. As Peter Thiel points out in his recent From Zero to One, today’s capitalism rewards the best monopolist, not the best competitor. Indeed, even the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division appeared to agree with Thiel in its 1995 guidelines on antitrust enforcement in innovation markets. It viewed intellectual property as a good monopoly, the rightful reward to innovators for developing a uniquely effective process or product. And its partner in federal antitrust enforcement, the Federal Trade Commission, has been remarkably quiescent in response to emerging data monopolies.

II. Propertizing Data

For B&M, intellectual property—or, at least, the returns accruing to intellectual insight or labor—plays a critical role in legitimating inequalities arising out of advanced technologies. They argue that “in the future, ideas will be the real scarce inputs in the world—scarcer than both labor and capital—and the few who provide good ideas will reap huge rewards.”[4] But many of the leading examples of profitable automation are not “ideas” per se, or even particularly ingenious algorithms. They are brute force feats of pattern recognition: for example, Google’s studying past patterns of clicks to see what search results, and what ads, are personalized to delight and persuade each of its hundreds of millions of users. The critical advantage there is the data, not the skill in working with it.[5] Google will demur, but if they were really confident, they’d license the data to other firms, confident that others couldn’t best their algorithmic prowess. They don’t, because the data is their critical, self-reinforcing advantage. It is a commonplace in big data literatures to say that the more data one has, the more valuable any piece of it becomes—something Googlers would agree with, as long as antitrust authorities aren’t within earshot.

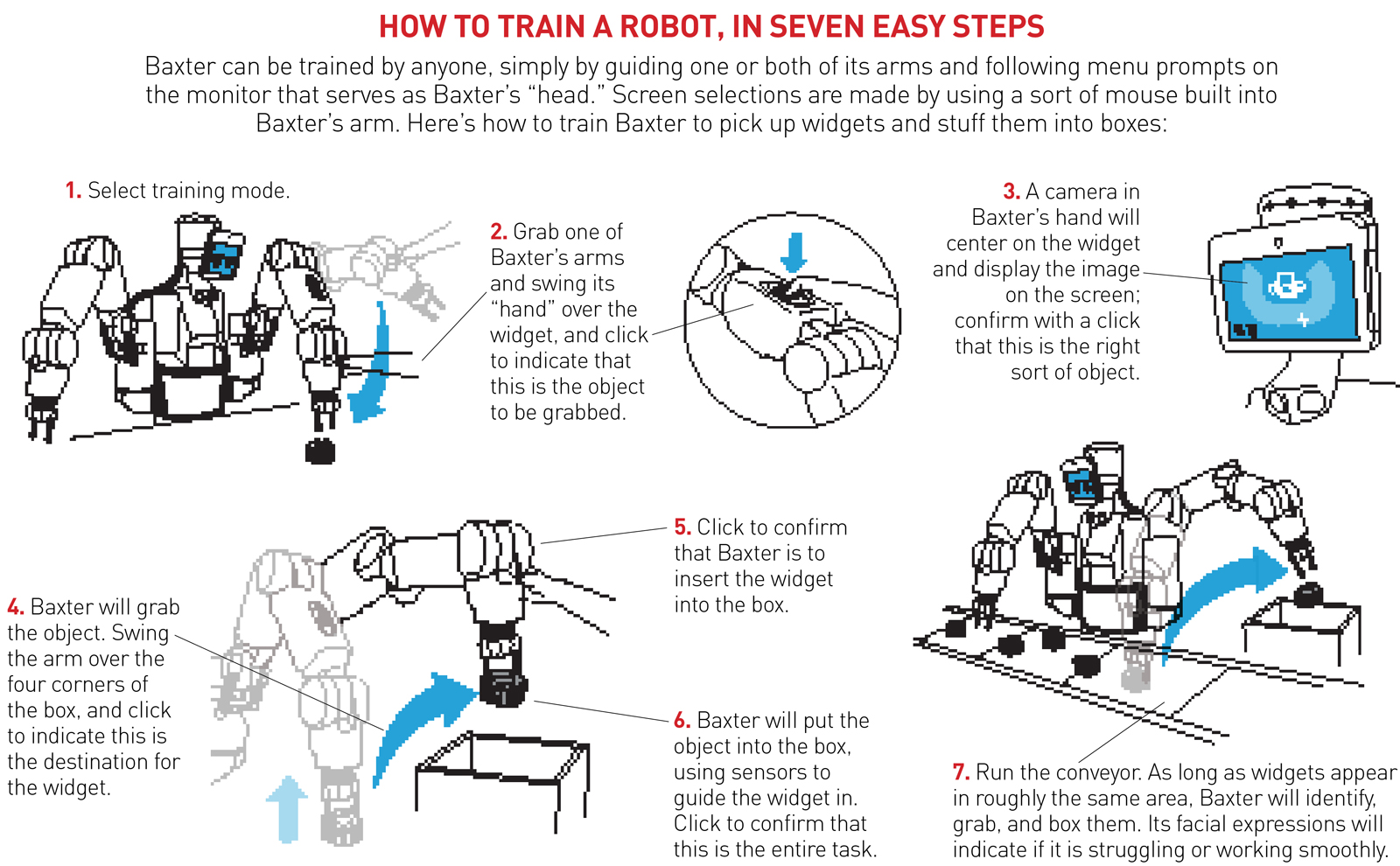

As sensors become more powerful and ubiquitous, feats of automated service provision and manufacture become more easily imaginable. The Baxter robot, for example, merely needs to have a trainer show it how to move in order to ape the trainer’s own job. (One is reminded of the stories of US workers flying to India to train their replacements how to do their job, back in the day when outsourcing was the threat du jour to U.S. living standards.)

From direct physical interaction with a robot, it is a short step to, say, programmed holographic or data-driven programming. For example, a surveillance camera on a worker could, after a period of days, months, or years, potentially record every movement or statement of the worker, and replicate it, in response to whatever stimuli led to the prior movements or statements of the worker.

B&M appear to assume that such data will be owned by the corporations that monitor their own workers. For example, McDonalds could train a camera on every cook and cashier, then download the contents into robotic replicas. But it’s just as easy to imagine a legal regime where, say, workers’ rights to the data describing their movements would be their property, and firms would need to negotiate to purchase the rights to it. If dance movements can be copyrighted, so too can the sweeps and wipes of a janitor. Consider, too, that the extraordinary advances in translation accomplished by programs like Google Translate are in part based on translations by humans of United Nations’ documents released into the public domain.[6] Had the translators’ work not been covered by “work-made-for-hire” or similar doctrines, they might well have kept their copyrights, and shared in the bounty now enjoyed by Google.[7]

Of course, the creativity of translation may be greater than that displayed by a janitor or cashier. Copyright purists might thus reason that the merger doctrine denies copyrightability to the one best way (or small suite of ways) of doing something, since the idea of the movement and its expression cannot be separated. Grant that, and one could still imagine privacy laws giving workers the right to negotiate over how, and how pervasively, they are watched. There are myriad legal regimes governing, in minute detail, how information flows and who has control over it.

I do not mean to appropriate here Jaron Lanier’s ideas about micropayments, promising as they may be in areas like music or journalism. A CEO could find some critical mass of stockers or cooks or cashiers to mimic even if those at 99% of stores demanded royalties for the work (of) being watched. But the flexibility of legal regimes of credit, control, and compensation is under-recognized. Living in a world where employers can simply record everything their employees do, or Google can simply copy every website that fails to adopt “robots.txt” protection, is not inevitable. Indeed, according to renowned intellectual property scholar Oren Bracha, Google had to “stand copyright on its head” to win that default.[8]

Thus B&M are wise to acknowledge the contestability of value in the contemporary economy. For example, they build on the work of MIT economists Daron Acemoglu and David Autor to demonstrate that “skill biased technical change” is a misleading moniker for trends in wage levels. The “tasks that machines can do better than humans” are not always “low-skill” ones (139). There is a fair amount of play in the joints in the sequencing of automation: sometimes highly skilled workers get replaced before those with a less complex and difficult-to-learn repertoire of abilities. B&M also show that the bounty predictably achieved via automation could compensate the “losers” (of jobs or other functions in society) in the transition to a more fully computerized society. By seriously considering the possibility of a basic income (232), they evince a moral sensibility light years ahead of the “devil-take-the-hindmost” school of cyberlibertarianism.

III. Proposals for Reform

Unfortunately, some of B&M’s other ideas for addressing the possibility of mass unemployment in the wake of automation are less than convincing. They praise platforms like Lyft for providing new opportunities for work (244), perhaps forgetting that, earlier in the book, they described the imminent arrival of the self-driving car (14-15). Of course, one can imagine decades of tiered driving, where the wealthy get self-driving cars first, and car-less masses turn to the scrambling drivers of Uber and Lyft to catch rides. But such a future seems more likely to end in a deflationary spiral than sustainable growth and equitable distribution of purchasing power. Like the generation traumatized by the Great Depression, millions subjected to reverse auctions for their labor power, forced to price themselves ever lower to beat back the bids of the technologically unemployed, are not going to be in a mood to spend. Learned helplessness, retrenchment, and miserliness are just as likely a consequence as buoyant “re-skilling” and self-reinvention.

Thus B&M’s optimism about what they call the “peer economy” of platform-arranged production is unconvincing. A premier platform of digital labor matching—Amazon’s Mechanical Turk—has occasionally driven down the wage for “human intelligence tasks” to a penny each. Scholars like Trebor Scholz and Miriam Cherry have discussed the sociological and legal implications of platforms that try to disclaim all responsibility for labor law or other regulations. Lilly Irani’s important review of 2MA shows just how corrosive platform capitalism has become. “With workers hidden in the technology, programmers can treat [them] like bits of code and continue to think of themselves as builders, not managers,” she observes in a cutting aside on the self-image of many “maker” enthusiasts.

The “sharing economy” is a glidepath to precarity, accelerating the same fate for labor in general as “music sharing services” sealed for most musicians. The lived experience of many “TaskRabbits,” which B&M boast about using to make charts for their book, cautions against reliance on disintermediation as a key to opportunity in the new digital economy. Sarah Kessler describes making $1.94 an hour labeling images for a researcher who put the task for bid on Mturk. The median active TaskRabbit in her neighborhood made $120 a week; Kessler cleared $11 an hour on her best day.

Resistance is building, and may create fairer terms online. For example, Irani has helped develop a “Turkopticon” to help Turkers rate and rank employers on the site. Both Scholz and Mike Konczal have proposed worker cooperatives as feasible alternatives to Uber, offering drivers both a fairer share of revenues, and more say in their conditions of work. But for now, the peer economy, as organized by Silicon Valley and start-ups, is not an encouraging alternative to traditional employment. It may, in fact, be worse.

Therefore, I hope B&M are serious when they say “Wild Ideas [are] Welcomed” (245), and mention the following:

- Provide vouchers for basic necessities. . . .

- Create a national mutual fund distributing the ownership of capital widely and perhaps inalienably, providing a dividend stream to all citizens and assuring the capital returns do not become too highly concentrated.

- Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps to clean up the environment, build infrastructure.

Speaking of the non-automatable, we could add the Works Progress Administration (WPA) to the CCC suggestion above. Revalue the arts properly, and the transition may even add to GDP.

Unfortunately, B&M distance themselves from the ideas, saying, “we include them not necessarily to endorse them, but instead to spur further thinking about what kinds of interventions will be necessary as machines continue to race ahead” (246). That is problematic, on at least two levels.

First, a sophisticated discussion of capital should be at the core of an account of automation, not its periphery. The authors are right to call for greater investment in education, infrastructure, and basic services, but they need a more sophisticated account of how that is to be arranged in an era when capital is extraordinarily concentrated, its owners have power over the political process, and most show little to no interest in long-term investment in the skills and abilities of the 99%. Even the purchasing power of the vast majority of consumers is of little import to those who can live off lightly taxed capital gains.

Second, assuming that “machines continue to race ahead” is a dodge, a refusal to name the responsible parties running the machines. Someone is designing and purchasing algorithms and robots. Illah Reza Nourbaksh’s Robot Futures suggests another metaphor:

Today most nonspecialists have little say in charting the role that robots will play in our lives. We are simply watching a new version of Star Wars scripted by research and business interests in real time, except that this script will become our actual world. . . . Familiar devices will become more aware, more interactive and more proactive; and entirely new robot creatures will share our spaces, public and private, physical and digital. . . .Eventually, we will need to read what they write, we will have to interact with them to conduct our business transactions, and we will often mediate our friendships through them. We will even compete with them in sports, at jobs, and in business. [9]

Nourbaksh nudges us closer to the truth, focusing on the competitive angle. But the “we” he describes is also inaccurate. There is a group that will never have to “compete” with robots at jobs or in business—rentiers. Too many of them are narrowly focused on how quickly they can replace needy workers with undemanding machines.

For the rest of us, another question concerning automation is more appropriate: how much can we be stuck with? A black-card-toting bigshot will get the white glove treatment from AmEx; the rest are shunted into automated phone trees. An algorithm determines the shifts of retail and restaurant workers, oblivious to their needs for rest, a living wage, or time with their families. Automated security guards, police, and prison guards are on the horizon. And for many of the “expelled,” the homines sacres, automation is a matter of life and death: drone technology can keep small planes on their tracks for hours, days, months—as long as it takes to execute orders.

B&M focus on “brilliant technologies,” rather than the brutal or bumbling instances of automation. It is fun to imagine a souped-up Roomba making the drudgery of housecleaning a thing of the past. But domestic robots have been around since 2000, and the median wage-earner in the U.S. does not appear to be on a fast track to a Jetsons-style life of ease.[10] They are just as likely to be targeted by the algorithms of the everyday, as they are to be helped by them. Mysterious scoring systems routinely stigmatize persons, without them even knowing. They reflect the dark side of automation—and we are in the dark about them, given the protections that trade secrecy law affords their developers.

IV. Conclusion

Debates about robots and the workers “struggling to keep up” with them are becoming stereotyped and stale. There is the standard economic narrative of “skill-biased technical change,” which acts more as a tautological, post hoc, retrodictive, just-so story than a coherent explanation of how wages are actually shifting. There is cyberlibertarian cornucopianism, as Google’s Ray Kurzweil and Eric Schmidt promise there is nothing to fear from an automated future. There is dystopianism, whether intended as a self-preventing prophecy, or entertainment. Each side tends to talk past the other, taking for granted assumptions and values that its putative interlocutors reject out of hand.

Set amidst this grim field, 2MA is a clear advance. B&M are attuned to possibilities for the near and far future, and write about each in accessible and insightful ways. The authors of The Second Machine Age claim even more for it, billing it as a guide to epochal change in our economy. But it is better understood as the kind of “big idea” book that can name a social problem, underscore its magnitude, and still dodge the elaboration of solutions controversial enough to scare off celebrity blurbers.

One of 2MA’s blurbers, Clayton Christensen, offers a backhanded compliment that exposes the core weakness of the book. “[L]earners and teachers alike are in a perpetual mode of catching up with what is possible. [The Second Machine Age] frames a future that is genuinely exciting!” gushes Christensen, eager to fold automation into his grand theory of disruption. Such a future may be exciting for someone like Christensen, a millionaire many times over who won’t lack for food, medical care, or housing if his forays fail. But most people do not want to be in “perpetually catching up” mode. They want secure and stable employment, a roof over their heads, decent health care and schooling, and some other accoutrements of middle class life. Meaning is found outside the economic sphere.

Automation could help stabilize and cheapen the supply of necessities, giving more persons the time and space to enjoy pursuits of their own choosing. Or it could accelerate arms races of various kinds: for money, political power, armaments, spying, stock trading. As long as purchasing power alone—whether of persons or corporations—drives the scope and pace of automation, there is little hope that the “brilliant technologies” B&M describe will reliably lighten burdens that the average person experiences. They may just as easily entrench already great divides.

All too often, the automation literature is focused on replacing humans, rather than respecting their hopes, duties, and aspirations. A central task of educators, managers, and business leaders should be finding ways to complement a workforce’s existing skills, rather than sweeping that workforce aside. That does not simply mean creating workers with skill sets that better “plug into” the needs of machines, but also, doing the opposite: creating machines that better enhance and respect the abilities and needs of workers. That would be a “machine age” welcoming for all, rather than one calibrated to reflect and extend the power of machine owners.

_____

Frank Pasquale (@FrankPasquale) is a Professor of Law at the University of Maryland Carey School of Law. His recent book, The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms that Control Money and Information (Harvard University Press, 2015), develops a social theory of reputation, search, and finance. He blogs regularly at Concurring Opinions. He has received a commission from Triple Canopy to write and present on the political economy of automation. He is a member of the Council for Big Data, Ethics, and Society, and an Affiliate Fellow of Yale Law School’s Information Society Project. He is a frequent contributor to The b2 Review Digital Studies section.

Back to the essay

_____

[1] One can quibble with the idea of automation as necessarily entailing “bounty”—as Yves Smith has repeatedly demonstrated, computer systems can just as easily “crapify” a process once managed well by humans. Nor is “spread” a necessary consequence of automation; well-distributed tools could well counteract it. It is merely a predictable consequence, given current finance and business norms and laws.

[2] For a definition of “crazy talk,” see Neil Postman, Stupid Talk, Crazy Talk: How We Defeat Ourselves by the Way We Talk and What to Do About It (Delacorte, 1976). For Postman, “stupid talk” can be corrected via facts, whereas “crazy talk” “establishes different purposes and functions than the ones we normally expect.” If we accept the premise of labor as a cost to be minimized, what better to cut than the compensation of the highest paid persons?

[3] Conversation with Sam Frank at the Swiss Institute, Dec. 16, 2014, sponsored by Triple Canopy.

[4] In Brynjolfsson, McAfee, and Michael Spence, “New World Order: Labor, Capital, and Ideas in the Power Law Economy,” an article promoting the book. Unfortunately, as with most statements in this vein, B&M&S give us little idea how to identify a “good idea” other than one that “reap[s] huge rewards”—a tautology all too common in economic and business writing.

[5] Frank Pasquale, The Black Box Society (Harvard University Press, 2015).

[6] Programs, both in the sense of particular software regimes, and the program of human and technical efforts to collect and analyze the translations that were the critical data enabling the writing of the software programs behind Google Translate.

[7] On translator employment, see also: https://twitter.com/JamesBessen/status/545212033453817857

[8] Bracha, “Standing Copyright Law on Its Head? The Googlization of Everything and the Many Faces of Property“; cf. Field v. Google.

[9] Illah Reza Nourbaksh, Robot Futures (MIT Press, 2013), pp. xix-xx.

[10] Erwin Prassler and Kazuhiro Kosuge, “Domestic Robotics,” in Bruno Siciliano and Oussama Khatib, eds., Springer Handbook of Robotics (Springer, 2008), p. 1258.