by Sarah Brouillette

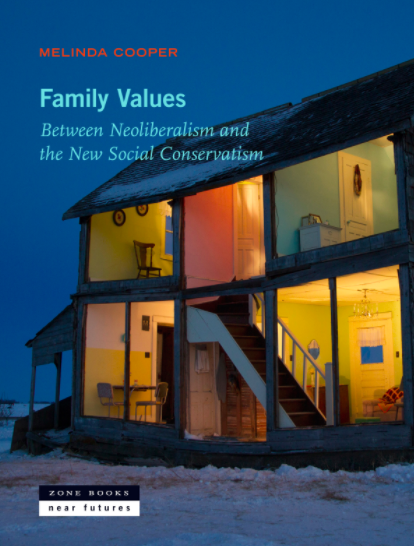

Review of Melinda Cooper, Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism (New York: Zone Books, 2017)

The basics of neoliberalism are by now well known. Pressured to be wary of public deficit spending, and trying to find ways to rejuvenate depressed economies, neoliberal governments cut spending on welfare and other social services, and turn the programs that do remain into job training “workfare.” Policies at the same time shift to give priority to the needs of businesses wanting to keep wages low, to offshore production, and to make few or no commitments to workers. The power of unions is undercut as a result, so it is decreasingly possible to look to that form of collectivity as a shelter.[1] Politicians, advisors, sympathetic management consultants and business professors meanwhile emphasize private initiative and personal merit as the keys to success. As a result, work has been trending toward the less regular, less routine, less secure, less protected by union membership, with wages stagnant and less likely to be supplemented by things like affordable public education, low rents, tax credits, and childcare benefit payments.

The working individual suited to this environment will naturally possess certain traits, as people are encouraged to look to themselves for more and more of what they need. Everything becomes a matter of personal responsibility: invest smartly for the future, take out a loan to pay for college, be your own brand, find your joy, “live your life.” If there is a culture of neoliberalism, it is all about interiority and the individual psychic life: therapeutic culture, because there is little state funding for mental health treatment. Find out who you really are, do what you love, look within, take your natural resilience as the base of every struggle and its overcoming; experience setbacks, Pop Idol style, as welcome occasions to overcome every hurdle. Self-improve. Self-actualize.

The causal relations are sometimes murky and eminently debatable. Don’t governments in fact fund wellness initiatives, especially targeting underprivileged communities? And what about all the counternarratives emphasizing the necessity of communities coming together – the British Tories’ “Big Society,” for instance? But the general account of neoliberalism is quite uniform. It pinpoints the force of biographization, responsibilization, individualization, self-management, a DIY ethos, and customization of personal preference as the lifeblood of the neoliberal order.[2]

Against all this, Melinda Cooper’s Family Values: Between Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism argues that the key social unit of neoliberalism is not the individual but the family, and not just any family but the family in perpetual crisis. She presents the postwar Fordist family wage – basically, a state-backed wage high enough to support a family with only one parent working – as a “mechanism for the normalization of gender and sexual relationships” (8), and for this reason sees no reason to lament its demise. As an “instrument of redistribution,” she writes, it “policed the boundaries between women and men’s work and white and black men’s labor” and was “inseparable from the imperative of sexual normativity” (23). “Few African American men enjoyed the family wage privileges of the unionized industrial labor force,” and their disproportionately high unemployment is evidence of the “multiple exclusions serving to define the boundaries of state-subsidized reproduction” (35-6).

Just as the “Fordist politics of class … established white, married masculinity as point of access to full social protection” (23), the fundamental concern for neoliberals like Gary Becker was how to respond to the breakdown of this masculinity and the family built around it. “Neoliberals are particularly concerned about the enormous social costs that derive from the breakdown of the stable Fordist family,” Cooper argues. They aim “to reestablish the private family as the primary source of economic security and the comprehensive alternative to the welfare state” (9). Basically, they want the traditional family intact as a compensation for precarity.

The data show that in the neoliberal era private family wealth is increasingly decisive in “shaping and restricting social mobility” (125), and this is a result of concerted policymaking. In the 1960s, inflation eroded the wealth at the top tiers, as it translated into the deflation of financial assets. Inflation was at the time understood in precisely this way, as a redistributive tax, “intensifying progressive tendencies” of the period: “Free-market economists insinuated that inflation was a form of state-sanctioned fraud – a covert tax designed to extort wealth from investors and transfer is to the lower classes” (127). The neoliberal “paradigm shift in American fiscal and monetary policy” sets about ending this redistributive movement. If the Employment Act of 1946 wanted to “promote maximum employment, production and purchasing power,” where wage and price inflation were understood as signs of growth and as “benign trade-offs to full employment,” the neoliberals overturned all this.

Figures such as Milton Friedman and Paul Volcker “turn[ed] inflation-targeting into the prime objective of monetary policy,” thus restricting the money supply and pushing up interest rates. Whereas bondholders in the 1970s saw assets depreciate and the Federal Reserve “deferred to the interests of unionized labor and welfare constituencies,” in the new era the Fed would strive “to repress wages and consumer prices in the service of asset price appreciation.” These policies led to a sure turnaround in the distribution of national income; the “share of national income flowing to financial investors went from negative or stagnant in the 1970s to ‘substantially positive’ in the 1980s”; while “labor’s share of national income declined proportionately” (134). By 1983, Cooper writes, “wealth concentration had reverted to its 1962 level and by the end of the decade had plummeted to levels comparable to 1929” (135).

There has thus been, at the top tier, a massive “resurgence of large family fortunes” (137). Nearly everywhere else, though, with stagnant wages, unemployment, and the transfer of the costs of things like higher education and health care back to families, lack of access to familial wealth can condemn one to a lifetime of debt. Hence Cooper’s argument about the importance of the family: intergenerational familial support in the form of housing, or money, or willingness to be signatories to loans, is a neoliberal necessity for many, and the pressure to combine dependence on parents with married coupledom just compounds the effect.[3] According to statistics gathered by the Pew Research Center, 1960 was the year in which people under 25 were most likely to live independently. In more recent decades, however, young people have been exhorted to invest in the future, save for retirement, and acquire assets (houses and university degrees). At the same time, and often in relation to this, they have been forced into debt and into insecure employment. No wonder they are more inclined to live with parents or partners. Of course, there is such a thing as a non-normative family, and perhaps living independently from relatives is not something we should unduly idealize. Cooper’s interest, though, is in what sort of family arrangements government programs prefer, and how preferences shift given combined pressure from neoliberal economic policy and the new social conservativism. We will return to her idealization of independence, however.

The more common argument, of course, is that neoliberalism is destructive to family life, as it encourages workers to be “low drag,” moveable, flexible, always working, losing any sense of a private life outside of work, and also alone in leisure in front of a personally selected entertainment service displayed on a privately watched device. Yet, as Annie McClanahan has recently argued, not many people are really these footloose mobile workers.[4] For most employers, it is probably more important that those they hire be replaceable than that they be mobile. Only workers in relatively elite sectors (high tech, higher education, entertainment) are in a better position if they can move from thing to thing without worrying about family obligations.[5]

This is not to deny that there is now also a more general animus against the restrictions and burdens of family life – the boredom of marriage, and drudgery of raising children (all captured so well by a show like Mad Men, for instance, which crystalizes the individualizing ethos so perfectly). However, there is just as much pressure to maintain the bonds of coupledom, and this tension between rejection and embrace may in fact be the point worth emphasizing. It seems that people are increasingly wondering if marriage is “worth it,” while decreasingly being able to exit it, and this is a cause of general anxiety, finding outlet in things like the dating site for adulterers, Ashley Madison, which was notorious for a minute in 2016 after its user data was stolen. When it turned out that most of the male customers were at least some of the time corresponding with bots rather than real women, I couldn’t help thinking that in a way it didn’t matter: the point is that users find an outlet for their sense of being stuck in a social relation (marriage!) on which they are dependent. Indeed, the bot’s lack of reality, lack of availability, is what makes the “affair” appealingly nonthreatening to the user’s IRL relationships. Moralistic attacks on these men – the fact that some of those caught are family-values conservatives is, to be sure, a rich irony – miss the point: they are not having affairs; they are staying in unhappy marriages that they depend on in various ways.

They depend on marriage because it is still the normative standard for people (if you aren’t married there is something wrong with you; if you don’t have kids you are deviant in some way). They depend on it in that they can’t afford a house without two salaries, because for tax purposes it is better to be a legally recognized couple, because the lifestyle they aspire to requires it, because caring for children alone is very hard, because shifting work hours and temporary contracts make the second salary a necessity, even if it too is precarious. They depend on it because they are too tired and generally physically weary to try to have any other sort of relationship. Being non-normative can feel like SO. MUCH. WORK. A film like 2009’s Up in the Air makes the point very well: the protagonist is the epitome of the roving high-powered executive entrepreneur (indeed, his job is to fire people), but his story is not a celebration of the escape from normativity. It is rather a lament about the psychic misery of solitude. The message is clear: couple up!

How did the family start to lose its normative power? For Cooper, conservatives skewering feminism, and more leftist thinkers trying to understand the foundations of neoliberalism, are in agreement about the force of 1960s and 1970s countercultural and antinormative critiques of the family. In Wolfgang Streeck’s analysis, the revolution in family law and intimate relationships – for example, the availability of no-fault divorce – destroyed the Fordist family wage because women were not stuck in the kitchen dependent on men any more. The family became a more flexible form because, in Cooper’s paraphrase of Streeck, feminists sought “an independent wage on a par with men,” eventually “transforming marriage from a long-term, noncontractual obligation into a contract that could be dissolved at will” (11). Cooper reads Eve Chiapello and Luc Boltanski’s argument as similar, in that they show how “the artistic left prepared the groundwork for the neoliberal assault on economic and social security by destroying its intimate foundations in the postwar family” (12). She quotes Nancy Fraser, also, who has written that “critique of the family wage … now supplies a good part of the romance that invests flexible capitalism with a higher meaning and moral point” (12). In each case, the idea is that feminism is somehow to blame for neoliberalization, because in seeking to free women from certain kinds of normative obligation and dependency they have demonized dependency in general, fetishizing independence from supports of any kind. Against these analyses, Cooper asks: what breakdown of the family, anyway? The apparent post-normativity of contemporary life is entirely compatible with the establishment of new norms. We continue to be form-determined after we no longer see social forms’ normative force. Put simply: the traditional family, which for Cooper is a family coerced into existence by exigency and normativity, is not broken enough.

The economy in depression no longer affords the state-supported Fordist wage, but the family is re-inscribed and reformulated even as it is queried and undermined by antinormative movements. If the foundations of neoliberal policy are thoroughly economic, neoconservativism enters Cooper’s account as a largely compatible reaction formation. The neoconservative agenda, formed deliberately against the liberation movements of the 1960s and their challenge to the normativity of the traditional family, served neoliberalization far more than the countercultural left’s challenges to social convention. Cooper argues that, whereas nostalgia for the Fordist wage became a “hallmark of the left,” neoconservatives, allied with thrifty neoliberals, preferred “the strategic reinvention of a much older, poor-law tradition of private family responsibility.” In a policy formation that reflected both neoliberal and neoconservative thought, social welfare was not to disappear, but instead to be made into “an immense federal apparatus for policing the private family responsibilities of the poor” (21).

As a public assistance program targeted at the noncontributing poor – workers paying into funds that would support them in the event of unemployment were always more palatable (34) – the fate of AFDC (Aid for Families with Dependent Children) is one of Cooper’s main cases. It allows her to show how social welfare extended to the poor – especially to single women, especially mothers, especially black mothers – became “associated with a general crisis of the American family” (29). As the composition of the program changed, with the number of African American women signing up outpacing that of white woman, and divorced or never-married women joined the rolls, fears were heightened. Because “racial and sexual normativities were truly foundational to the social order of American Fordism, determining just who would be included and who would be excluded from the redistributive benefits of the social wage” (36), the inclusivity evident in the 1960s in the AFDC’s provision for non-married mothers proved to be short-lived. Arguments for reinstating the stability offered by the traditional family had significant influence at this juncture.

Nor were these arguments solely made by conservatives. In the 1960s there was in fact significant leftist promotion of the African American male-breadwinner family and a related impetus against “non-normative lifestyles of unattached African American women” (37); hence the tendency to identify the AFDC as a cause of family breakdown while promoting the “male breadwinner’s wage” (41). An article by Richard A. Cloward and Frances Fox Piven, published in The Nation in 1966 and presented as “a strategy to end poverty,” laments that the state was “substituting check-writing machines for male wage earners,” thereby “robb[ing] men of manhood, women of husbands, and children of father.” The authors continue: “To create a stable monogamous family, we need to provide men (especially Negro men) with the opportunity to be men, and that involves enabling them to perform occupationally” (qtd. 42).

What they saw were “perverse disincentives to family formation built into the AFDC program” (43), whereas women left more to their own devices would naturally be more likely to find men to support them. With the 1970s economic downturn, and anxieties directed at inflation in particular, the program became a touchstone for debates for neoconservatives formulating their “new political philosophy of non-redistributive family values” (47). While neoliberals “called for an ongoing reduction in budget allocations dedicated to welfare—intent on undercutting any possibility that the social wage might compete with the free-market wage,” neoconservatives advocated an expanded role for state in regulating sexuality. On both fronts, the point was the urgent necessity of “reinstating the family as the foundation of social and economic order” (49).

Cooper discusses Milton Friedman’s concern that the “natural obligations” that “once compelled children to look after their parents in old age” have given way to “an impersonal system of social insurance whose long-term effect is to usurp the place of the family” (58). Friedman wrote that whereas once “Children helped their parents out of love or duty,” they now “contribute to the support of someone else’s parents out of compulsion and fear” (qtd. 58). State-based redistribution was a poor substitute for proper familial support and wealth transmission. For Gary Becker, also, the postwar welfare state destroys the “natural altruism of the family” (60). Becker’s theory of human capital is perhaps the premier theorization of individual self-management and self-appreciation. Michel Foucault treated Becker’s work as exemplary of the way that neoliberal analyses entail “replacement every time of homo economicus as partner of exchange with a homo economicus as entrepreneur of himself, being for himself his own capital … a capital that we will call human capital inasmuch as the ability-machine of which it is the income cannot be separated from the human individual who is its bearer.”[6] Becker also featured recently in a Merriam-Webster tweet of the term “human capital” – “turning people into statistics since 1799,” the tweet quipped – which linked to the full dictionary entry, where Becker’s work is cited as “taking a holistic view of a person’s life and experiences as they can be applied within the workforce.” Becker took personal investment in one’s own human capital appreciation as preferable to state investment (the benefits of high human capital only accruing to oneself, after all), and thus supported rising tuition costs and the student loan industry as a major part of the growing importance of private credit. Yet Cooper shows that his arguments also preferred a supportive wealth-generating family: the older generations would back student loans where necessary, as they naturally want children and grandchildren to bear human capital that self-appreciates at a greater pace and with results that are more lucrative. Becker celebrated Ronald Reagan for restoring kinship bonds.

Reagan drastically cut the AFDC, before Bill Clinton eliminated it. It was replaced with the TANF program (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families), whose availability was contingent on states’ willingness to track down and enforce paternity obligations. TANF’s defenders claimed it is better for a woman and her children to be reliant on alimony and child support than to turn to the government for assistance (67). Here we get to the heart of Cooper’s refutation of the idea that neoliberalism privileges the footloose free agent. In fact, in her account, neoliberalism is more likely to pressure people to sustain unhealthy and unsustainable family and intimate relationships, including tying children to fathers who do not know them or want them. Clinton’s extensive welfare reform reflected and codified what she calls “a new bipartisan consensus on the social value of monogamous, legally validated relationships.” His government reformed welfare spending while devising “initiatives to promote the moral obligations of family, including a special budget allocation to finance marriage promotion programs and … bonus funds to states that could demonstrate that they had successfully reduced illegitimate births without increasing the abortion rate” (68). Barack Obama’s “healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood” initiatives continued in this direction.

Cooper suggestively connects these initiatives to the “first experiment in federal relief ever implemented by Congress”: the 1865 creation of the Freedmen’s Bureau following the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. Before 1863, slaves were precluded from legally sanctioned marriage. The Freedman’s Bureau instructed that freedom to participate in the labor market came with “the right to marry and the responsibility to support wife and child” (79). Its support for freed slaves entailed a vigorous campaign to promote marriage, with Bureau agents authorized to perform marriages and a “sustained pedagogy of domestic life, schooling men in the notion that they were to become the breadwinners of the family and women in a new kind of economic dependence” (80). There were penalties for people cohabiting without marriage; and Bureau-assigned wage scales that penalized women, precisely because of the “social costs of dependency” that fell upon the state if forced to support unmarried women and their children (81).

Like the more recent insistence that women secure alimony and child support before turning to welfare, these policies empowered men to assert rights over women and children. Indeed, the assumptions upon which they were based were not fundamentally threatened until the 1960s liberalization of family law, which made divorce easier and eased the stigmatizing of non-marital unions and cohabitation. “For an all too brief moment,” she argues, “revised AFDC rules allow divorced or never-married women and their children to live independently of a man while receiving a state-guaranteed income free of moral conditions” (97). That moment is over, however. “The modern child support system serves to demonstrate that the state is willing to enforce—indeed create—legal relationships of familial obligation and dependence where none have been established by mutual consent,” Cooper writes (105).

We should pause here now on the figure of the never-married woman living independently thanks to welfare. Cooper argues that, in a context of relatively healthy public welfare spending, and of the pressures put on states by countercultural and antinormative activisms, there was a time when social welfare was “making women independent of individual men and freeing them from the obligations of the private family” (97). Hence, the fuel for the neoconservative backlash that soon followed – a backlash that gained traction because of the failing economy to which neoliberals were also turning their attention. A perfect storm. Yet Cooper’s celebration of the period in which social welfare possibly freed women from the constraints of marriage has her falling back into the trap she dismantles elsewhere: nostalgia for state provision.

The image of the single woman with children, living with a state-based income “free of moral conditions,” reads as an idealization. Certainly, supporting children as a single parent on welfare has never been a cakewalk; and, are we meant to conclude that “freeing” men from the burdens of paternity is an unalloyed boon to women? She needs this figure, though. Cooper’s idealization of the state-supported single mother alerts us to the fact that her ultimate objection is not to social welfare but rather to the restriction of its benefits to the Fordist white male breadwinner, and to the way welfare programs get tied to normative policies and programs emphasizing the preferability of turning to family, especially marriage, to marshal the necessary resources to get by.[7] She avoids the stronger critique of social welfare, which might emphasize the global accumulative regime and resource extraction on which US prosperity was built, how nation-based welfare disperses the benefits of prosperity to some and not others, and the welfare state’s various regulatory and pacifying functions.[8]

Does neoliberalism feel different to some people simply because it follows on the moment of postwar prosperity and the relatively expansive Keynesian social welfare that flowed from it, in which there was palpable faith in the civic virtue attending government spending on social programs? Neoliberal policies have threatened protections and comforts that these programs offered to some people – people like American and British university professors, who produce the analyses of the unique wrongs of the neoliberal order. Is all the worry about neoliberalism just a symptom of the decline of the hegemony of liberal democracy?

The economy that supported the pre-neoliberal era of relatively high wages, and relatively generous public deficit spending on welfare and education, was also hugely resource extractive and suburbanizing. The capacity to redistribute wealth more evenly in the US was, in addition, contingent upon broader economic transformation that required dispossessions, expulsions, enclosures, primitive accumulations, US hegemony propped up by global wars, and the origins of the whole phenomenon of US industrial triumph after WWII in wartime accumulation and relative devastation across Europe.[9] Wherever one looks, the accumulation of wealth requires these devastations, making even the lushest times at the ADFC, and the possibility for a temporary flourishing of alternative kinds of family structures, into a troubled gain. For these reasons, it may be that work that avoids the terminology of neoliberalism, or uses it warily – work by Endnotes, by Silvia Federici, or by Robert Brenner, for instance – provides better purchase on contemporary conditions. Because when they fail to name the fundamental, global, totalizing causes of policy shifts, accounts of neoliberalism miss the ruthlessly intensifying dynamics of capital accumulation that are simply propelled onward with extended credit.[10]

Finally, if Keynesian social welfare is a wage supplement designed to encourage consumer spending, in which sense is it wise to pit it against the dominance of commerce and private interests? If extensive public deficit spending on social programs and neoliberal monetarism are just different ways of managing the economy, and if one takes the capitalist economy as fundamentally anathema to universal human flourishing, to what extent should we worry about the difference that neoliberalism makes? Family Values doesn’t quite answer these questions. However, it does do the crucially important work of historicizing the rise of private credit in relation to family-values conservativism, and dismantling the left-liberal tendency to lament neoliberalization because it clawed back the gains of the immediate postwar period. Without suggesting that no gains were made, Cooper shows how they were thoroughly mitigated by normative racial, sexual and gender ascription – ascription that determined how to divvy up Fordism’s generous provisions, and that continues to push people, especially the already suffering, into unwanted contracts in life and work.

Notes

[1] For a recent account along these lines see Wendy Brown, Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution (New York: Zone Books, 2015).

[2] See for instance Ronen Shamir, “The age of responsibilization: on market-embedded morality,” Economy and Society (37.1: 2008): 1-19.

[3] I discuss Cooper’s blistering account of the student loan industry elsewhere.

[4] Annie McClanahan, “Becoming Non-Economic: Human Capital Theory and Wendy Brown’s Undoing the Demos,” Theory & Event 20.2 (2017): 510-519.

[5] Even scholars suggesting that, in being less interested in keeping people in regular work, crisis-era capitalism allows for “queer liberation” from cis-hetero norms, insist in the next breath that some elements of queer life are tolerable and easy assimilated – think pink washing and gay marriage – and some are not.

[6] Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France 1978-1979, trans. Graham Burchell (Palgrave, 2008): 226.

[7] In an earlier work, where the figure of the state-supported single mother is absent, her take is more ambivalent. She argues that the welfare state “undertakes to protect life by redistributing the fruits of national wealth to all its citizens, even those who cannot work, but in exchange it imposes a reciprocal obligation: its contractors must in turn give their lives to the nation” (Melinda Cooper, Life as Surplus: Biotechnology and Capitalism in the Neoliberal Era [University of Washington Press, 2008]: 8).

[8] Gavin Walker has recently argued that “the function of ‘welfare’ within capitalism has never been something separate from its workings; rather, it is something co-emergent and central to the operation of the capital-relation itself”: “Rather than being a political development in which capital’s violence is ameliorated through social spending, we should rather understand the welfare state as the primary mechanism through which the process of primitive accumulation can be continuously sustained in the advanced capitalist countries” (“The ‘Ideal Total Capitalist”: On the State-Form in the Critique of Political Economy,” Crisis & Critique 3.3 [2016]: 434-455).

[9] For an account along these lines see “Misery and Debt,” Endnotes 2 (April 2010): 20-51.

[10] I owe this point to discussion with Tim Kreiner.