by Devin Zane Shaw

In an interview from 2012, Jacques Rancière states in response to a question about the role of dialogue in philosophy:

I don’t believe in the virtue of dialogue in the form of: here’s a thinker, here’s another thinker, they’re going to debate amongst themselves and that’s going to produce something. My idea is that it’s always books that enter into dialogue and not people….Dialogue is never, for me, what it appears to be, which is something like the lightning flash of an encounter, a live exchange.[i]

We should, then, approach the recent Recognition or Disagreement: A Critical Encounter on the Politics of Freedom, Equality, and Identity (Columbia University Press, 2016), with a similarly circumspect attitude.

The core of the book, edited by Katia Genel and Jean-Philippe Deranty, is the debate between Rancière and Axel Honneth that took place at the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt in June 2009, but it also includes a supplementary text by each author and an essay from each editor. Given that the editors’ essays comprise, at eighty pages, forty-five percent of the text, one should be particularly attentive to the ways in which their interventions shape the reception of the debate that was the book’s occasion. Against the editors, I want to argue here that this debate demonstrates the incompatibility of Honneth’s and Rancière’s respective projects. Moreover, Rancière’s work cannot be reconceptualized in the terms of Honneth’s liberal iteration of critical theory without sacrificing precisely those parts of his thought that are the most inventive, interesting, and politically and intellectually subversive.

My differences with Genel and Deranty can best be summarized through our respective interpretations of Rancière’s claim that, in his critique of Honneth, he has reconstructed a “‘’ [sic] conception of the theory of recognition” (95). In my view, Rancière critically appropriates the terms of “recognition” to show what it would require to become a theory of dissensus and disagreement. Deranty outlines what he takes to be Rancière’s concern with a theory of recognition that ranges from Althusser’s Lesson to Disagreement in order to demonstrate an “in-principle agreement” between Rancière and Honneth (37). First, he argues that many of the examples from Disagreement are based on historical research that Rancière conducted in the 1970s. Then Deranty adduces passages that mention recognition, such as Alain Faure and Rancière’s “Introduction” to La parole ouvrière (1976), where they refer to political struggle as “the desire to be recognized which communicates with the refusal to be despised” (quoted on 38). He also cites an early interpretation of Pierre-Simon Ballanche’s account of the plebeian revolt on Aventine Hill (an episode which also plays a crucial role in the argument of Disagreement) where Rancière writes that the “rebellion was characterized by the fact that it recognized itself as a speaking subject and gave itself a name.”[ii] Rancière continues, though: “Roman patrician power refused to accept that the sounds uttered from the mouths of the plebeians were speech, and that the offspring of their unions should be given the name of a lineage.”[iii] This description has little to do with Honneth’s account of recognition, in which individuals recognize their freedom and the freedom of others as mediated by established social institutions. And then Deranty concedes that “Rancière just disagrees with some of the key concepts used by Honneth,” which undermines the verbal parallels that he draws upon to signal their agreement (36, my emphasis). Indeed, their principled dispute about their respective concepts undermines the very possibility of an “in-principle agreement.” Therefore, to evaluate the relationship between Rancière’s egalitarian politics and Honneth’s theory of recognition we cannot rely on verbal parallels; instead, we must address how the concepts of recognition and disagreement play out in relation to a theory of the political subject, the relation between politics and the political, and problems concerning what Rancière calls “the police” and social normativity.

To address these questions, I will begin with the final essay included in Recognition or Disagreement, Honneth’s “Of the Poverty of Our Liberty: The Greatness and Limits of Hegel’s Doctrine of Ethical Life.” Earlier in the book, Honneth claims that “all kinds of political orders have to give a certain description or legitimation for who is included in the political community,” and, indeed, political philosophy often aims to supply the legitimation for a given society’s norms that decide how and whether individuals and their practices are included or excluded from the political order (115). Hegel, on Honneth’s account, demonstrates the logical and practical coherence of the social objectivity of the various types of individual freedom, that is, how freedom relates, through recognition, to politics, work, and love.

In the book’s concluding essay, Honneth examines, first, how Hegel reconciles two common, subjective concepts of individual freedom within his account of objective freedom as it is realized in ethical life. Both subjective concepts are abstract sides of modern political freedom. For Hegel, the transition to modernity entails conceptualizing social institutions as “making possible the realization of freedom” (160). In other words, on Hegel’s account, individual freedoms are mediated through institutions—and institutions are mediated and produced through the actualization or realization of individual freedoms. Thus, when Hegel reconciles the two subjective concepts of freedom, which approximate what Isaiah Berlin calls negative and positive freedom, he demonstrates that both fail to incorporate the objectivity of freedom as it is embodied in concrete social institutions. According to the “negative” concept of freedom, an individual is free insofar as they are unhindered by the actions of others. While Hegel incorporates this incomplete concept of freedom within his system as “abstract right,” which ensures state protections of individual life, property, and freedom of contract, he faults negative freedom for lacking a positive determination of what the subject can do, socially, with freedom. According to the “positive” concept of freedom, which Hegel largely derives from Kant, the basis of morality is autonomy, the self-legislating and self-reflexive activity of the subject. While this concept of freedom gives a positive foundation to what morality is, it nonetheless remains subjective, lacking a concrete relationship to social objectivity.

These negative and positive concepts of freedom are, therefore, in Hegel’s terms, “merely” subjective, while Hegel aims to demonstrate that individual freedom is objective, that is, reflected and recognized within objective social institutions. This concept of objective freedom is not limited merely to how we understand social institutions. To say that freedom is objective delimits an important intersubjective feature of individual freedom. As Honneth points out, Hegel argues that we cannot rely on Kantian models of autonomy in friendship or love, since the self-limitation of my freedom in the experience of friendship or love is not a self-limitation; it is “precisely that the other person is a condition of realizing my own, self-chosen ends” (164). The realization of a given individual’s freedom entails concrete social situations that implicate the freedom of others, and it is because social institutions mediate our relations with others that they have objective reality. Hegel—and by extension, Honneth—maintains that institutions receive normative justification insofar as they reflect and embody the practices of individuals’ freedoms, and that social institutions, in turn, engender the emergence and expansion of individual freedoms.

Now, one can see why Honneth follows Hegel through the discussion of objective freedom in the doctrine of ethical life: what both the negative and positive subjective concepts of freedom lack is recognition. In our institutions, Honneth suggests, we should be able to recognize not only our own intentions but also the intentions of other subjects. In addition, Hegel identifies three ethical spheres in which each individual’s freedoms are realized in relation to others’: personal relationships, the market economy, and politics. For these reasons, Honneth argues that the “general structure” of Hegel’s doctrine of ethical life, despite some shortcomings, “remains sound even today,” and that this doctrine provides “us with a normative vocabulary that we can use to assess the respective value of the various freedoms we practice” (169; 167). Nonetheless, Honneth also faults Hegel for treating “as sacrosanct” three historically specific institutions as the outcome of the self-realization of objective spirit: the family—“guided by the patriarchal prejudices of his own day”—the capitalist market economy, and constitutional monarchy (171). While Hegel did not explicitly address the possibility that these institutions could be transformed to “make them more amenable to the basic demand for relations of reciprocity among equals,” Honneth contends that Hegel’s account of morality hints toward how political practice can revise social norms and reorganize social institutions to make them more democratic (172). According to Honneth’s revision of Hegel, the inclusion of liberal rights and the possibility for “moral self-positioning” allows for individuals to engage in “morally articulated protest” (174). Thus Honneth allows for a continued moral progress within societies and social institutions to a degree that was not envisioned by Hegel.

*

Despite his Hegelian framework, and despite his debts to the Frankfurt School, Honneth’s project shares some of the central concerns of mainstream Anglo-American political philosophy today: the emphasis on processes of justification and establishing conditions of justice in order to evaluate institutional and normative frameworks. By contrast, Rancière’s political thought shares neither the methods nor goals of mainstream political philosophy. Todd May has already explored in detail the differences between Rancière and mainstream political philosophy (including Rawls, Nozick, Amartya Sen and Iris Marion Young). In May’s account, these political philosophers rely, whether they are proponents or critics of distributive theories of justice, on a concept of “passive equality”: “the creation, preservation, or protection of equality by governmental institutions.”[iv] Rancière, though, makes the stronger polemical claim that political philosophy embeds itself in, and offers justification for, regimes of inequality that he calls “the police” or “policing.” One of the most striking features of Rancière’s work is his claim that what we typically call politics, even in its most democratic forms (voting, deliberation, governance, and popular legitimation), is policing. In Disagreement, Rancière defines the police as:

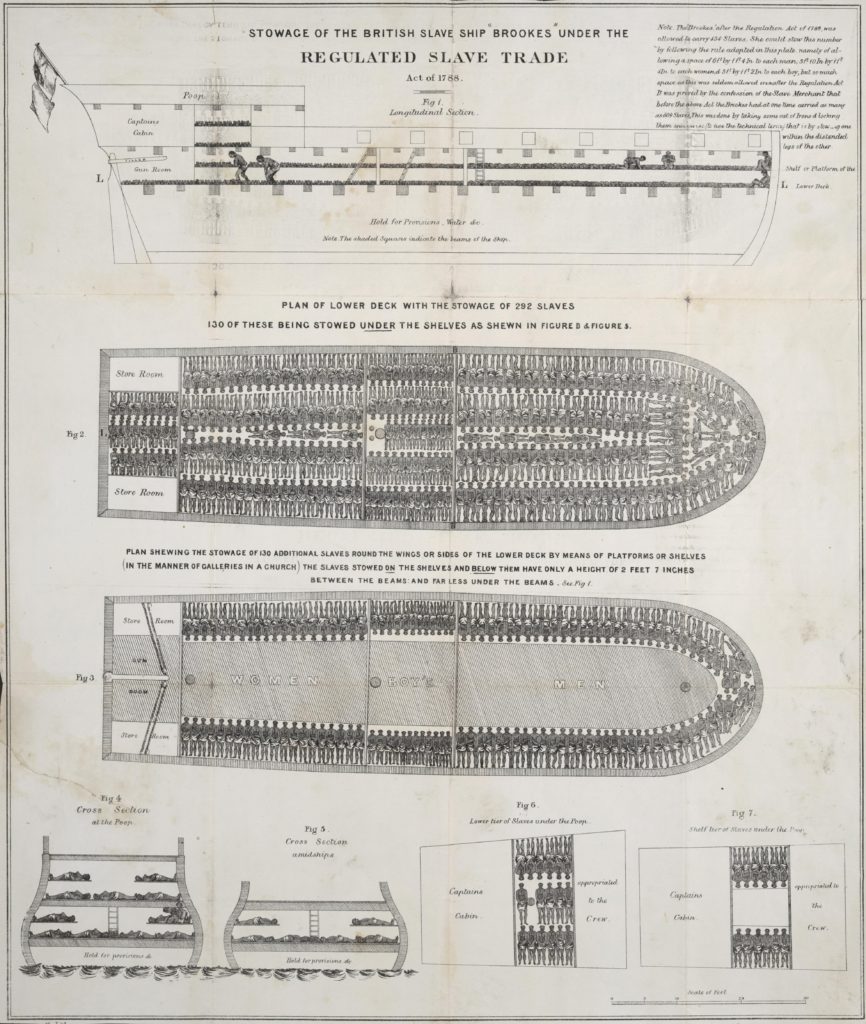

first an order of bodies that defines the allocation of ways of doing, ways of being, and ways of saying, and sees that those bodies are assigned by name to a particular place and task; it is an order of the visible and the sayable that sees that a particular activity is visible and that another is not, that this speech is understood as discourse and another as noise.[v]

Since this definition of the police sounds very close to the way that Rancière often glosses his concept of “the distribution of the sensible,”[vi] we should specify that policing produces and reproduces relations of inequality, the stratification of roles within a given distribution of the sensible that partition individuals and groups according to inclusion and exclusion, such as those whose task it is to rule and those whose task it is to obey. Moreover, on Rancière’s account, politics—in May’s terms, “active equality”—is a dynamic of collective engagement and revolt that aims to subvert and resist the stratification and coercion of policing and social institutions. Given that Honneth’s account of recognition emphasizes how social institutions mediate and engender individual freedoms, it then follows that in Rancière’s terms Honneth’s theory of recognition would not be an account of politics as much as it is an account—though a progressive one at that—of policing.

And yet, in “Critical Questions on the Theory of Recognition,” his critique of Honneth (and Chapter Three of the book), Rancière does not use the terms “police” or “policing.” Instead, he begins with the conditional hypothesis that his differences with Honneth are best articulated by treating their respective approaches as competing theories of recognition. At the outset, however, he signals his critical intent by suggesting that “the term ‘recognition’ might also emphasize a relationship between already existing entities,” these entities being individuals and established social institutions (83). When, then, Rancière concludes that he’s sketched, through his critique of Honneth, his own theory of recognition, he’s appropriated the language of critical theory to articulate a politics of dissensus and disagreement.

Rancière pursues this hypothesis—that he and Honneth are outlining competing theories of recognition—in order to locate their central points of disagreement. In Disagreement, Rancière defines disagreement (la mésentente) as a specific kind of political challenge to a given order of policing, “a determined kind of speech situation in which one of the interlocutors at once understands [entend] and does not understand [entend] what the other is saying.”[vii] In French, the term la mésentente plays on different connotations of the verb entendre, between “to hear” and “to understand.” On Rancière’s account, the politics of disagreement emerges when the marginalized or oppressed (what he calls “the part with no part”) within a given social order challenge the ways in which society is policed, and often these challenges are phrased in terms that have readily accepted meanings within society. However, politically contentious terms, such as equality, rights, or justice are given inventive new meanings that challenge the normative frameworks of a given regime of policing; the part with no part who are contesting injustice and the police can “hear” the same demands but “understand” entirely different things. Many political theorists lament this ambiguity and aim to define it away. However, Rancière argues that the ambiguity of our contentious terms and ideals makes dissensus possible. That is, this ambiguity makes it possible to identify how these politically contentious terms circulate between policing and politics, how they come to articulate and combat inequality and coercion. For example: justice, for some, means due process and equal consideration before the law, while justice for movements such as Black Lives Matter opens on to both a broad indictment of how so-called due process legitimates injustice against African-Americans who are victims of police violence, and a broader vision of transformative social justice.

In “Critical Questions on the Theory of Recognition,” Rancière uses disagreement in a broader, dialogical sense rather than its specific, political sense. He argues that dialogue—to be truly dialogical—must be an “act of communication [which] is already an act of translation, located on a terrain that we don’t master” (84). Dialogue always involves translation, distortion, but also invention; in terms of philosophy, it means that both interlocutors must think outside of their usual terminology: distortion remains “at the heart of any mutual dialogue, at the heart of the form of universality on which dialogue relies” (84). But Rancière also suggests that dialogue, in its more specific, political sense, requires acknowledging the “asymmetry in positions” between interlocutors. This claim summarizes his differences with Habermas, which he had previously outlined in Disagreement: acknowledging how asymmetry and power distort the ideals of political dialogue entails, in Rancière’s account, a stringent form of universalism that demands philosophers to confront not just institutional barriers to democratic deliberation, but also how the processes of deliberation function to exclude certain forms of political speech and action. Thus Rancière’s critical question: to what degree does Honneth’s theory of recognition rely on the presupposition that the demands of political subjects have always already been mediated by social institutions?

To confront this question, Rancière proposes three working definitions of recognition. Two reflect common usage: on the one hand, recognition means the concurrence of a perception with prior knowledge, as when we recognize a friend, location, or information; on the other hand, recognition in the moral sense designates how we recognize other individuals as autonomous beings like ourselves. In both cases, Rancière notes, “re-cognition” functions as an act of confirmation. He then hypothesizes that recognition could also be conceptualized in the terms of what he calls a distribution of the sensible. Recognition, then, “focuses on the configuration of the field in which things, persons, situations, and arguments can be identified” (85). In this sense, recognition comes prior to any act of confirmation—and the critique of recognition entails disagreement over the conditions in which persons, things, or situations are understood as such.

We could ask, for instance, how is it that a given regime of policing frames some enunciations as political demands against injustice and others as merely subjective complaints or even noise? And we could use an analysis of this situation to attack the broader norms that legitimate this distribution of speech and noise. While Rancière acknowledges that Honneth’s account of recognition “echoes” his own polemical account, he raises a crucial question: to what degree does Honneth’s account rely on the two connotations of the common usage, presuming a stable distribution of the sensible or normative framework that relies on an “identitarian conception of the subject” that conflicts with a “conception of social relations as mutual” or dynamically or socially constructed (85)?

First, Rancière contends that Honneth embraces an “anthropological-psychological” concept of the subject that is heavily indebted to a Hegelian “juridical definition of the person” (87). Thus Honneth’s account of the subject’s struggle for recognition emphasizes the affirmation of self-identity and self-integrity within the intersubjective structure of recognition. In other words, it’s the same integral individual subject who is seeks recognition within a multiplicity of situations related to love, work, or politics. Then, Rancière argues that this juridical model of the integral identity of the subject conflicts with its claim to articulating intersubjective social agency—a point encapsulated in Honneth’s summary of love and recognition in the book: “in friendship and love my experience is precisely that the other person is a condition of my realizing my own, self-chosen ends” (164). To say that love involves two individuals realizing their respective ends and interests through another is overly juridical. To Honneth, Rancière counterposes love as it is found in À la recherche du temps perdu, where Proust describes love as a dynamic and aesthetic construction of an other. Rancière writes:

What appears at the beginning is the confused apparition of a multiplicity, an impersonal patch on a beach. Slowly the patch appears as a group of young girls, but is still a kind of impersonal patch. There are many metamorphoses in that patch, in the multiplicity of young girls, through to the moment when the narrative personifies this impersonal multiplicity, gives it the face of one person, the object of love, Albertine. (88)

Rancière offers this counternarrative to show how our theoretical frameworks delimit the possibilities of social agency that we are able to recognize—a criticism that Honneth subsequently accepts.

Rancière’s attention to this point can perhaps explain how Rancière’s terminology can be alternately powerful and abstract. When he opposes the politics of equality to policing, it readily calls to mind clashes between protestors and cops, though politics cannot be reduced to these terms. However, when he defines those subjects who confront the established order as the part with no part, this definition is far more abstract than saying marginalized and oppressed. But Rancière relies on this level of abstraction in order to avoid delimiting conditions of political agency that could delimit who this part is because it could exclude groups who have yet to emerge and who we cannot foresee.

In general, for Rancière, political subjects are neither self-identical nor self-integral. Instead, political subjects emerge through a dynamic of what he calls disidentification, the rejection of the roles, places, and tasks assigned to bodies within a given regime of policing. We could interpret Proust’s description of love, then, as a metaphor for the dynamic of political subjectivation: political subjects emerge first as a multiplicity, at first an impersonal patch in the social field, until it takes shape through the invention of a name—for instance, #blacklivesmatter or #NoDAPL—for a collective disruption of or rebellion against the police order. Given that all regimes of policing are instantiations of social inequality and coercion, politics is, for Rancière, by definition egalitarian. It is equality, he argues, that leads to a much more exacting concept of universality than an account of politics that neglects the asymmetry between the political subjects who exist by virtue of contesting the social order and the established order of policing. Politics enacts the affirmation of “an equal capacity to discuss common affairs”; in other words, politics enacts the intellectual and political equality of anybody and everybody (93).

The task of political thought is to ascertain how politics involves a “polemical configuration of the universal” (94). The Black Lives Matter movement began with a call for justice for Mike Brown in Ferguson, but, according to Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, its next stage involves both “engaging with the social forces that have the capacity to shut down sectors of work or production until our demands to stop police terrorism are met” and movement building through solidarity, which addresses how, while African-Americans “suffer most from the blunt force trauma of the American criminal justice system,” the broader normative framework of “law-and-order politics” functions to oppress the poor in general.[viii] From a standpoint informed by Rancière, the goal of political thought would be to identify the movements and practices that drive “the process of spreading the power of equality” in the here and now, to identify how specific movements involve a polemical force of universality to subvert and combat the normative frameworks of a given police order (94). Far from endorsing a theory of recognition, Rancière has redefined recognition as a politics of dissensus and disagreement.

*

Thus we have good reason to doubt Deranty’s claim of an in-principle agreement between Rancière and Honneth. Indeed, the editors and I reach very different conclusions regarding the significance of this debate because they accept Honneth’s theoretical framework to interpret it, while I refuse to subsume Rancière’s concepts under Honneth’s. The point here, though, is not establishing who has read Rancière or Honneth correctly, but to examine how these interpretations delimit what each thinker believes is politically possible and feasible.

Our first difference concerns the supposed common ground shared by Rancière and Honneth. Though Rancière explicitly chooses to oppose “politics” (la politique), rather than “the political” (le politique) to “the police”, Honneth and the editors equivocate between “politics” and “the political.” However, the terms, especially in French philosophy, are distinct—which means Rancière has made a deliberate conceptual choice.[ix] Politics, on his account, designates a dynamic activity, while “the political” carries the connotation of an original, fundamental political sphere upon which policing has supervened. For Honneth, then, when Rancière discusses equality, he’s describing either an “original definition of the political community” (115) or a political anthropology in which human beings “are constituted by a wish or a desire to be equal to all others,” and this “egalitarian desire…brings about the exceptional moment of politics” (99). In their “Critical Discussion” included in the book, Rancière rightly rebuts both of these characterizations. He holds that if politics takes place, it does so through an egalitarian praxis opposed to the police. To treat Rancière’s politics as a political anthropology, imputing particular desires or motives to political subjects, implies that the debate is about whether human beings are motivated by either a desire for recognition or for equality. We could, in that case, resolve the debate with a political anthropology of desire.

If this is not enough reason to reject Honneth’s way of framing the debate, he also characterizes recognition and disagreement as two complementary forms of struggle with different scopes—but this categorization carries with it an implicit normative claim that recognition is more practical. He argues that Rancière brusquely reduces “the political,” considered as “a stratified normative order of principles of recognition,” to policing (103). Therefore Rancière interprets this stratified normative order too rigidly, when these norms are given to conflicts over their meaning, that is, subject to reinterpretation and revision. For Honneth, the revisability of the normative order allows us to conceive of two types of political intervention: an internal struggle for recognition and an external struggle for recognition. In Honneth’s terms, Rancière focuses exclusively on the external struggle for recognition, which, while it combats the “political order as such,” ignores the “reformist” ambitions of the internal struggle for recognition that aims to reinterpret existing normative principles to make social institutions and their normative frameworks more democratic and inclusive.

But Honneth’s distinction between the internal and external struggles for recognition is not merely descriptive, but also normative: given, he claims, the difficulties in formulating injustice in revolutionary terms, it’s more important in day-to-day politics to “deal with these small projects of redefinition or of reappropriation of the existing modes of political legitimation” (106). Unlike Honneth, Rancière does not prescribe the scope of political struggle within a given situation, since such a prescription functions to legitimate or delegitimize choices we make about what is to be done. These choices cannot be evaluated outside of the context of political struggle itself. But Honneth’s normative preference is part of his philosophical framework: if the freedom of individuals is engendered and mediated by social institutions and norms, and if self-integrity is one of the primary ends of the theory of recognition, then individuals should aim to reform and reinterpret these institutions and norms incrementally.

From Rancière’s perspective, even if we grant that political freedom is sometimes engendered by existing social institutions, this does not entail that all parts of society should recognize these institutions as engendering their freedom. Those who are marginalized and oppressed could just as equally recognize how a given institution has functioned to exclude, marginalize, oppress, or immiserate them. The goal of politics for these political subjects need not or should not be—nor should we prescribe their goal to be—the reform of or formal recognition within these institutions that have historically oppressed them. From Rancière’s standpoint, it is right for the part with no part to combat and transform the very normative principles that legitimate and reinforce these institutions of inequality, and to prescribe reform rather than radical normative transvaluation serves to delegitimize the possibility of formulating and enacting broader goals of political struggle.

Thus while Recognition or Disagreement presents the debate between Rancière and Honneth, it speaks to broader issues about the scope and aims of contemporary political thought. The contrast between Honneth and Rancière ably demonstrates Rancière’s stubborn refusal to engage in the processes of justification valorized by mainstream political theory—indeed, it serves as a stark reminder of how engaging in these problems often, (and in Rancière’s view, always) entails accepting profound social inequalities. However, this book is also important because it shows that if we mainstream Rancière’s work, as Genel and Deranty attempt to do, we lose those parts of his work that are most subversive and inventive—and we are left with only Honneth.

Devin Zane Shaw teaches philosophy at Carleton University. He is the author of Egalitarian Moments: From Descartes to Rancière (Bloomsbury, 2016) and Freedom and Nature in Schelling’s Philosophy of Art (Bloomsbury, 2010).

Notes

[i] Jacques Rancière, The Method of Equality: Interviews with Laurent Jeanpierre and Dork Zabunyan, transl. Julie Rose. Malden: Polity, 2016, p. 183.

[ii] Quoted on 38, but the reference is incomplete. See Rancière, Staging the People: The Proletarian and His Double, transl. David Fernbach. London: Verso, 2011, p. 37.

[iii] Rancière, Staging the People, 37.

[iv] Todd May, The Political Thought of Jacques Rancière: Creating Equality. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008, p. 3.

[v] Rancière, Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy, transl. Julie Rose. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999, p. 29.

[vi] As Rancière defines it in Recognition or Disagreement, a distribution of the sensible is “a relation between occupations and equipments, between being in a specific space and time, performing specific activities, and being endowed with capacities of seeing, saying, and doing that ‘fit’ those activities. A distribution of the sensible is a set of relations between sense and sense, that is, between a form of sensory experience and an interpretation that makes sense of it. It is a matrix that defines a whole organization of the visible, the sayable, and the thinkable” (136).

[vii] Disagreement, p. x.

[viii] Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016, pp. 217, 211.

[ix] See Samuel A. Chambers, The Lessons of Rancière. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, pp. 50–57.

Aamir R. Mufti: Forget English! Orientalisms and World Literatures (Harvard University Press, 2016)

Aamir R. Mufti: Forget English! Orientalisms and World Literatures (Harvard University Press, 2016)