by Zachary Loeb

~

Technological optimism is a dish best served from a stage. Particularly if it’s a bright stage in front of a receptive and comfortably seated audience, especially if the person standing before the assembled group is delivering carefully rehearsed comments paired with compelling visuals, and most importantly if the stage is home to a revolving set of speakers who take turns outdoing each other in inspirational aplomb. At such an event, even occasional moments of mild pessimism – or a rogue speaker who uses their fifteen minutes to frown more than smile – serve to only heighten the overall buoyant tenor of the gathering. From TED talks to the launching of the latest gizmo by a major company, the person on a stage singing the praises of technology has become a familiar cultural motif. And it is a trope that was alive and drawing from that well at the 2016 Personal Democracy Forum, the theme of which was “The Tech We Need.”

Over the course of two days some three-dozen speakers and a similar number of panelists gathered to opine on the ways in which technology is changing democracy to a rapt and appreciative audience. The commentary largely aligned with the sanguine spirit animating the founding manifesto of the Personal Democracy Forum (PDF) – which frames the Internet as a potent force set to dramatically remake and revitalize democratic society. As the manifesto boldly decrees, “the realization of ‘Personal Democracy,’ where everyone is a full participant, is coming” and it is coming thanks to the Internet. The two days of PDF 2016 consisted of a steady flow of intelligent, highly renowned, well-meaning speakers expounding on the conference’s theme to an audience largely made up of bright caring individuals committed to answering that call. To attend an event like PDF and not feel moved, uplifted or inspired by the speakers would be a testament to an empathic failing. How can one not be moved? But when one’s eyes are glistening and when one’s heart is pounding it is worth being wary of the ideology in which one is being baptized.

To critique an event like the Personal Democracy Forum – particularly after having actually attended it – is something of a challenge. After all, the event is truly filled with genuine people delivering (mostly) inspiring talks. There is something contagious about optimism, especially when it presents itself as measured optimism. And besides, who wants to be the jerk grousing and grumbling after an activist has just earned a standing ovation? Who wants to cross their arms and scoff that the criticism being offered is precisely the type that serves to shore up the system being criticized? Pessimists don’t often find themselves invited to the after party. Thus, insofar as the following comments – and those that have already been made – may seem prickly and pessimistic it is not meant as an attack upon any particular speaker or attendee. Many of those speakers truly were inspiring (and that is meant sincerely), many speakers really did deliver important comments (that is also meant sincerely), and the goal here is not to question the intentions of PDF’s founders or organizers. Yet prominent events like PDF are integral to shaping the societal discussions surrounding technology – and therefore it is essential to be willing to go beyond the inspirational moments and ask: what is really being said here?

For events like PDF do serve to advance an ideology, whether they like it or not. And it is worth considering what that ideology means, even if it forces one to wipe the smile from one’s lips. And when it comes to PDF much of its ideology can be discovered simply by dissecting the theme for the 2016 conference: “The Tech We Need.”

“The Tech”

What do you (yes, you) think of when you hear the word technology? After all, it is a term that encompasses a great deal, which is one of the reasons why Leo Marx (1997) was compelled to describe technology as a “hazardous concept.” Eyeglasses are technology, but so too is Google Glass. A hammer is technology, and so too is a smart phone. In other words, when somebody says “technology is X” or “technology does Q” or “technology will result in R” it is worth pondering whether technology really is, does or results in those things, or if what is being discussed is really a particular type of technology in a particular context. Granted, technology remains a useful term, it is certainly a convenient shorthand (one which very many people [including me] are guilty of occasionally deploying), but in throwing the term technology about so casually it is easy to obfuscate as much as one clarifies. At PDF it seemed as though a sentence was not complete unless it included a noun, a verb and the word technology – or “tech.” Yet what was meant by “tech” at PDF almost always meant the Internet or a device linked to the Internet – and qualifying this by saying “almost” is perhaps overly generous.

Thus the Internet (as such), web browsers, smart phones, VR, social networks, server farms, encryption, other social networks, apps, and websites all wound up being pleasantly melted together into “technology.” When “technology” encompasses so much a funny thing begins to happen – people speak effusively about “technology” and only name specific elements when they want to single something out for criticism. When technology is so all encompassing who can possibly criticize technology? And what would it mean to criticize technology when it isn’t clear what is actually meant by the term? Yes, yes, Facebook may be worthy of mockery and smart phones can be used for surveillance but insofar as the discussion is not about the Internet but “technology” on what grounds can one say: “this stuff is rubbish”? For even if it is clear that the term “technology” is being used in a way that focuses on the Internet if one starts to seriously go after technology than one will inevitably be confronted with the question “but aren’t hammers also technology?” In short, when a group talks about “the tech” but by “the tech” only means the Internet and the variety of devices tethered to it, what happens is that the Internet appears as being synonymous with technology. It isn’t just a branch or an example of technology, it is technology! Or to put this in sharper relief: at a conference about “the tech we need” held in the US in 2016 how can one avoid talking about the technology that is needed in the form of water pipes that don’t poison people? The answer: by making it so that the term “technology” does not apply to such things.

The problem is that when “technology” is used to only mean one set of things it muddles the boundaries of what those things are, and what exists outside of them. And while it does this it allows people to confidently place trust in a big category, “technology,” whereas they would probably have been more circumspect if they were just being asked to place trust in smart phones. After all, “the Internet will save us” doesn’t have quite the same seductive sway as “technology will save us” – even if the belief is usually put more eloquently than that. When somebody says “technology will save us” people can think of things like solar panels and vaccines – even if the only technology actually being discussed is the Internet. Here, though, it is also vital to approach the question of “the tech” with some historically grounded modesty in mind. For the belief that technology is changing the world and fundamentally altering democracy is nothing new. The history of technology (as an academic field) is filled with texts describing how a new tool was perceived as changing everything – from the compass to the telegraph to the phonograph to the locomotive to the [insert whatever piece of technology you (the reader) can think of]. And such inventions were often accompanied by an, often earnest, belief that these inventions would improve everything for the better! Claims that the Internet will save us, invoke déjà vu for those with a familiarity with the history of technology. Carolyn Marvin’s masterful study When Old Technologies Were New (1988) examines the way in which early electrical communications methods were seen at the time of their introduction, and near the book’s end she writes:

Predictions that strife would cease in a world of plenty created by electrical technology were clichés breathed by the influential with conviction. For impatient experts, centuries of war and struggle testified to the failure of political efforts to solve human problems. The cycle of resentment that fueled political history could perhaps be halted only in a world of electrical abundance, where greed could not impede distributive justice. (206)

Switch out the words ”electrical technology” for “Internet technology” and the above sentences could apply to the present (and the PDF forum) without further alterations. After all, PDF was certainly a gathering of “the influential” and of “impatient experts.”

And whenever “tech” and democracy are invoked in the same sentence it is worth pondering whether the tech is itself democratic, or whether it is simply being claimed that the tech can be used for democratic purposes. Lewis Mumford wrote at length about the difference between what he termed “democratic” and “authoritarian” technics – in his estimation “democratic” systems were small scale and manageable by individuals, whereas “authoritarian” technics represented massive systems of interlocking elements where no individual could truly assert control. While Mumford did not live to write about the Internet, his work makes it very clear that he did not consider computer technologies to belong to the “democratic” lineage. Thus, to follow from Mumford, the Internet appears as a wonderful example of an “authoritarian” technic (it is massive, environmentally destructive, turns users into cogs, runs on surveillance, cannot be controlled locally, etc…) – what PDF argues for is that this authoritarian technology can be used democratically. There is an interesting argument there, and it is one with some merit. Yet such a discussion cannot even occur in the confusing morass that one finds oneself in when “the tech” just means the Internet.

Indeed, by meaning “the Internet” but saying “the tech” groups like PDF (consciously or not) pull a bait and switch whereby a genuine consideration of what “the tech we need” simply becomes a consideration of “the Internet we need.”

“We”

Attendees to the PDF conference received a conference booklet upon registration; it featured introductory remarks, a code of conduct, advertisements from sponsors, and a schedule. It also featured a fantastically jarring joke created through the wonders of, perhaps accidental, juxtaposition; however, to appreciate the joke one needed to open the booklet so as to be able to see the front and back cover simultaneously. Here is what that looked like:

Get it?

Hilarious.

The cover says “The Tech We Need” emblazoned in blue over the faces of the conference speakers, and the back is an advertisement for Microsoft stating: “the future is what we make it.” One almost hopes that the layout was intentional. For, who the heck is the “we” being discussed? Is it the same “we”? Are you included in that “we”? And this is a question that can be asked of each of those covers independently of the other: when PDF says “we” who is included and who is excluded? When Microsoft says “we” who is included and who is excluded? Of course, this gets muddled even more when you consider that Microsoft was the “presenting sponsor” for PDF and that many of the speakers at PDF have funding ties to Microsoft. The reason this is so darkly humorous is that there is certainly an argument to be made that “the tech we need” has no place for mega-corporations like Microsoft, while at the same time the booklet assures that “the future is what we [Microsoft] make it.” In short: the future is what corporations like Microsoft will make it…which might be very different from the kind of tech we need.

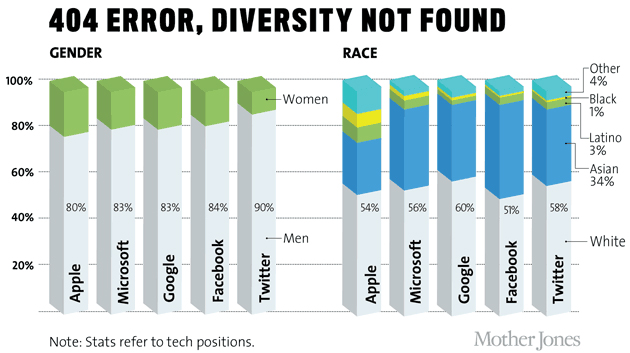

In considering the “we” of PDF it is worth restating that this is a gathering of well-meaning individuals who largely seem to want to approach the idea of “we” with as much inclusivity as possible. Yet defining a “we” is always fraught, speaking for a “we” is always dangerous, and insofar as one can think of PDF with any kind of “we” (or “us”) in mind the only version of the group that really emerges is one that leans heavily towards describing the group actually present at the event. And while one can certainly speak about the level (or lack) of diversity at the PDF event – the “we” who came together at PDF is not particularly representative of the world. This was also brought into interesting relief in some other amusing ways: throughout the event one heard numerous variations of the comment “we all have smart phones” – but this did not even really capture the “we” of PDF. While walking down the stairs to a session one day I clearly saw a man (wearing a conference attendee badge) fiddling with a flip-phone – I suppose he wasn’t included in the “we” of “we all have smart phones.” But I digress.

One encountered further issues with the “we” when it came to the political content of the forum. While the booklet states, and the hosts repeated over and over, that the event was “non-partisan” such a descriptor is pretty laughable. Those taking to the stage were a procession of people who had cut their teeth working for MoveOn and the activists represented continually self-identified as hailing from the progressive end of the spectrum. The token conservative speaker who stepped onto the stage even made a self-deprecating joke in which she recognized that she was one of only a handful (if that) of Republicans present. So, again, who is missing from this “we”? One can be a committed leftist and genuinely believe that a figure like Donald Trump is a xenophobic demagogue – and still recognize that some of his supporters might have offered a very interesting perspective to the PDF conversation. After all, the Internet (“the tech”) has certainly been used by movements on the right as well – and used quite effectively at that. But this part of a national “we” was conspicuously absent from the forum even if they are not nearly so absent from Twitter, Facebook, or the population of people owning smart phones. Again, it is in no way shape or form an endorsement of anything that Trump has said to point out that when a forum is held to discuss the Internet and democracy that it is worth having the people you disagree with present.

Another question of the “we” that is worth wrestling with revolves around the way in which events like PDF involve those who offer critical viewpoints. If, as is being argued here, PDF’s basic ideology is that the Internet (“the tech”) is improving people’s lives and will continue to do so (leading towards “personal democracy”) – it is important to note that PDF welcomed several speakers who offered accounts of some of the shortcomings of the Internet. Figures including Sherry Turkle, Kentaro Toyama, Safiya Noble, Kate Crawford, danah boyd, and Douglas Rushkoff all took the stage to deliver some critical points of view – and yet in incorporating such voices into the “we” what occurs is that these critiques function less as genuine retorts and more as safety valves that just blow off a bit of steam. Having Sherry Turkle (not to pick on her) vocally doubt the empathetic potential of the Internet just allows the next speaker (and countless conference attendees) to say “well, I certainly don’t agree with Sherry Turkle.” Nevertheless, one of the best ways to inoculate yourself against the charge of unthinking optimism is to periodically turn the microphone over to a critic. But perhaps the most important things that such critics say are the ways in which they wind up qualifying their comments – thus Turkle says “I’m not anti-technology,” Toyama disparages Facebook only to immediately add “I love Facebook,” and fears regarding the threat posed by AI get laughed off as the paranoia of today’s “apex predators” (rich white men) being concerned that they will lose their spot at the top of the food chain. The environmental costs of the cloud are raised, the biased nature of algorithms is exposed – but these points are couched against a backdrop that says to the assembled technologists “do better” not “the Internet is a corporately controlled surveillance mall, and it’s overrated.” The heresies that are permitted are those that point out the rough edges that need to be rounded so that the pill can be swallowed. To return to the previous paragraph, this is not to say that PDF needs to invite John Zerzan or Chellis Glendinning to speak…but one thing that would certainly expose the weaknesses of the PDF “we” is to solicit viewpoints that genuinely come from outside of that “we.” Granted, PDF is more TED talk than FRED talk.

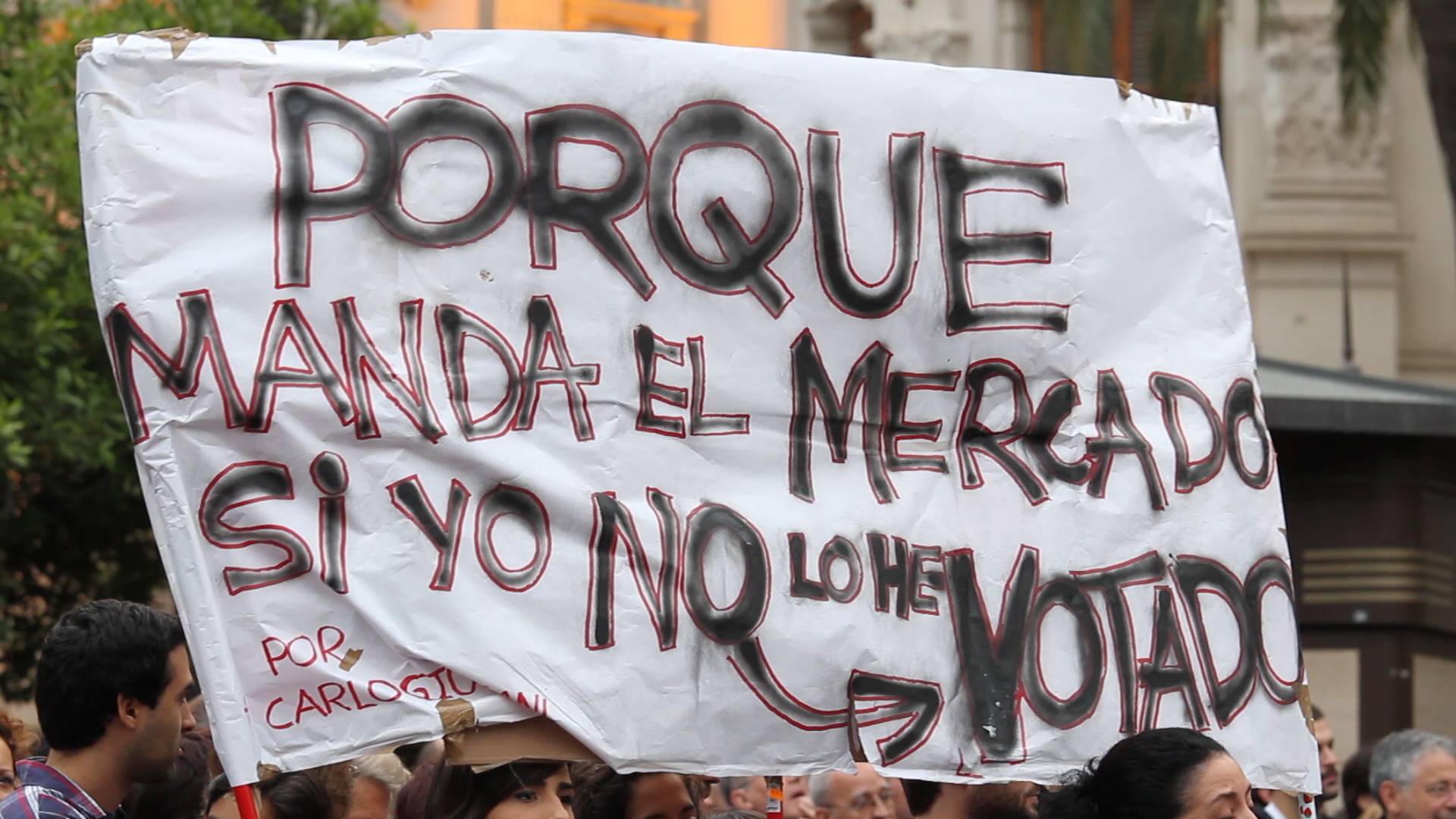

And of course, and most importantly, one must think of the “we” that goes totally unheard. Yes, comments were made about the environmental cost of the cloud and passing phrases recognized mining – but PDF’s “we” seems to mainly refer to a “we” defined as those who use the Internet and Internet connected devices. Miners, those assembling high-tech devices, e-waste recyclers, and the other victims of those processes are only a hazy phantom presence. They are mentioned in passing, but not ever included fully in the “we.” PDF’s “the tech we need” is for a “we” that loves the Internet and just wants it to be even better and perhaps a bit nicer, while Microsoft’s we in “the future is what we make it” is a “we” that is committed to staying profitable. But amidst such statements there is an even larger group saying: “we are not being included.” That unheard “we” being the same “we” from the classic IWW song “we have fed you all for a thousand years” (Green et al 2016). And as the second line of that song rings out “and you hail us still unfed.”

“Need”

When one looks out upon the world it is almost impossible not to be struck by how much is needed. People need homes, people need –not just to be tolerated – but accepted, people need food, people need peace, people need stability, people need the ability to love without being subject to oppression, people need to be free from bigotry and xenophobia, people need…this list could continue with a litany of despair until we all don sackcloth. But do people need VR headsets? Do people need Facebook or Twitter? Do those in the possession of still-functioning high-tech devices need to trade them in every eighteen months? Of course it is important to note that technology does have an important role in meeting people’s needs – after all “shelter” refers to all sorts of technology. Yet, when PDF talks about “the tech we need” the “need” is shaded by what is meant by “the tech” and as was previously discussed that really means “the Internet.” Therefore it is fair to ask, do people really “need” an iPhone with a slightly larger screen? Do people really need Uber? Do people really need to be able to download five million songs in thirty seconds? While human history is a tale of horror it requires a funny kind of simplistic hubris to think that World War II could have been prevented if only everybody had been connected on Facebook (to be fair, nobody at PDF was making this argument). Are today’s “needs” (and they are great) really a result of a lack of technology? It seems that we already have much of the tech that is required to meet today’s needs, and we don’t even require new ways to distribute it. Or, to put it clearly at the risk of being grotesque: people in your city are not currently going hungry because they lack the proper app.

The question of “need” flows from both the notion of “the tech” and “we” – and as was previously mentioned it would be easy to put forth a compelling argument that “the tech we need” involves water pipes that don’t poison people with lead, but such an argument is not made when “the tech” means the Internet and when the “we” has already reached the top of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. If one takes a more expansive view of “the tech” and “we” than the range of what is needed changes accordingly. This issue – the way “tech” “we” and “need” intersect – is hardly a new concern. It is what prompted Ivan Illich (1973) to write, in Tools for Conviviality, that:

People need new tools to work with rather than tools that ‘work’ for them. They need technology to make the most of the energy and imagination each has, rather than more well-programmed energy slaves. (10)

Granted, it is certainly fair to retort “but who is the ‘we’ referred to by Illich” or “why can’t the Internet be the type of tool that Illich is writing about” – but here Illich’s response would be in line with the earlier referral to Mumford. Namely: accusations of technological determinism aside, maybe it’s fair to say that some technologies are oversold, and maybe the occasional emphasis on the way that the Internet helps activists serves as a patina that distracts from what is ultimately an environmentally destructive surveillance system. Is the person tethered to their smart phone being served by that device – or are they serving it? Or, to allow Illich to reply with his own words:

As the power of machines increases, the role of persons more and more decreases to that of mere consumers. (11)

Mindfulness apps, cameras on phones that can be used to film oppression, new ways of downloading music, programs for raising money online, platforms for connecting people on a political campaign – the user is empowered as a citizen but this empowerment tends to involve needing the proper apps. And therefore that citizen needs the proper device to run that app, and a good wi-fi connection, and… the list goes on. Under the ideology captured in the PDF’s “the tech we need” to participate in democracy becomes bound up with “to consume the latest in Internet innovation.” Every need can be met, provided that it is the type of need, which the Internet can meet. Thus the old canard “to the person with a hammer every problem looks like a nail” finds its modern equivalent in “to the person with a smart phone and a good wi-fi connection, every problem looks like one that can be solved by using the Internet.” But as for needs? Freedom from xenophobia and oppression are real needs – undoubtedly – but the Internet has done a great deal to disseminate xenophobia and prop up oppressive regimes. Continuing to double down on the Internet seems like doing the same thing “we” have been doing and expecting different results because finally there’s an “app for that!”

It is, again, quite clear that those assembled at PDF came together with well-meaning attitudes, but as Simone Weil (2010) put it:

Intentions, by themselves, are not of any great importance, save when their aim is directly evil, for to do evil the necessary means are always within easy reach. But good intentions only count when accompanied by the corresponding means for putting them into effect. (180)

The ideology present at PDF emphasizes that the Internet is precisely “the means” for the realization of its attendees’ good intentions. And those who took to the stage spoke rousingly of using Facebook, Twitter, smart phones, and new apps for all manner of positive effects – but hanging in the background (sometimes more clearly than at other times) is the fact that these systems also track their users’ every move and can be used just as easily by those with very different ideas as to what “positive effects” look like. The issue of “need” is therefore ultimately a matter not simply of need but of “ends” – but in framing things in terms of “the tech we need” what is missed is the more difficult question of what “ends” do we seek. Instead “the tech we need” subtly shifts the discussion towards one of “means.” But, as Jacques Ellul, recognized the emphasis on means – especially technological ones – can just serve to confuse the discussion of ends. As he wrote:

It must always be stressed that our civilization is one of means…the means determine the ends, by assigning us ends that can be attained and eliminating those considered unrealistic because our means do not correspond to them. At the same time, the means corrupt the ends. We live at the opposite end of the formula that ‘the ends justify the means.’ We should understand that our enormous present means shape the ends we pursue. (Ellul 2004, 238)

The Internet and the raft of devices and platforms associated with it are a set of “enormous present means” – and in celebrating these “means” the ends begin to vanish. It ceases to be a situation where the Internet is the mean to a particular end, and instead the Internet becomes the means by which one continues to use the Internet so as to correct the current problems with the Internet so that the Internet can finally achieve the… it is a snake eating its own tail.

And its own tale.

Conclusion: The New York Ideology

In 1995, Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron penned an influential article that described what they called “The Californian Ideology” which they characterized as

promiscuously combin[ing] the free-wheeling spirit of the hippies and the entrepreneurial zeal of the yuppies. This amalgamation of opposites has been achieved through a profound faith in the emancipatory potential of the new information technologies. In the digital utopia, everybody will be both hip and rich. (Barbrook and Cameron 2001, 364)

As the placing of a state’s name in the title of the ideology suggests, Barbrook and Cameron were setting out to describe the viewpoint that was underneath the firms that were (at that time) nascent in Silicon Valley. They sought to describe the mixture of hip futurism and libertarian politics that worked wonderfully in the boardroom, even if there was now somebody in the boardroom wearing a Hawaiian print shirt – or perhaps jeans and a hoodie. As companies like Google and Facebook have grown the “Californian Ideology” has been disseminated widely, and though such companies periodically issued proclamations about not being evil and claimed that connecting the world was their goal they maintained their utopian confidence in the “independence of cyberspace” while directing a distasteful gaze towards the “dinosaurs” of representative democracy that would dare to question their zeal. And though it is a more recent player in the game, one is hard-pressed to find a better example than Uber of the fact that this ideology is alive and well.

The Personal Democracy Forum is not advancing the Californian Ideology. And though the event may have featured a speaker who suggested that the assembled “we” think of the “founding fathers” as start-up founders – the forum continually returned to the questions of democracy. While the Personal Democracy Forum shares the “faith in the emancipatory potential of the new information technologies” with Silicon Valley startups it seems less “free-wheeling” and more skeptical of “entrepreneurial zeal.” In other words, whereas Barbrook and Cameron spoke of “The Californian Ideology” what PDF makes clear is that there is also a “New York Ideology.” Wherein the ideological hallmark is an embrace of the positive potential of new information technologies tempered by the belief that such potential can best be reached by taming the excesses of unregulated capitalism. Where the Californian Ideology says “libertarian” the New York Ideology says “liberation.” Where the Californian Ideology celebrates capital the New York Ideology celebrates the power found in a high-tech enhanced capitol. The New York Ideology balances the excessive optimism of the Californian Ideology by acknowledging the existence of criticism, and proceeds to neutralize this criticism by making it part and parcel of the celebration of the Internet’s potential. The New York Ideology seeks to correct the hubris of the Californian Ideology by pointing out that it is precisely this hubris that turns many away from the faith in the “emancipatory potential.” If the Californian Ideology is broadcast from the stage at the newest product unveiling or celebratory conference, than the New York Ideology is disseminated from conferences like PDF and the occasional skeptical TED talk. The New York Ideology may be preferable to the Californian Ideology in a thousand ways – but ultimately it is the ideology that manifests itself in the “we” one encounters in the slogan “the tech we need.”

Or, to put it simply, whereas the Californian Ideology is “wealth meaning,” the New York Ideology is “well-meaning.”

Of course, it is odd and unfair to speak of either ideology as “Californian” or “New York.” California is filled with Californians who do not share in that ideology, and New York is filled with New Yorkers who do not share in that ideology either. Yet to dub what one encounters at PDF to be “The New York Ideology” is to indicate the way in which current discussions around the Internet are not solely being framed by “The Californian Ideology” but also by a parallel position wherein faith in Internet enabled solutions puts aside its libertarian sneer to adopt a democratic smile. One could just as easily call the New York Ideology the “Tech On Stage Ideology” or the “Civic Tech Ideology” – perhaps it would be better to refer to the Californian Ideology as the SV Ideology (silicon valley) and the New York Ideology as the CV ideology (civic tech). But if the Californian Ideology refers to the tech campus in Silicon Valley than the New York Ideology refers to the foundation based in New York – that may very well be getting much of its funding from the corporations that call Silicon Valley home. While Uber sticks with the Californian Ideology, companies like Facebook have begun transitioning to the New York Ideology so that they can have their panoptic technology and their playgrounds too. Whilst new tech companies emerging in New York (like Kickstarter and Etsy) make positive proclamations about ethics and democracy by making it seem that ethics and democracy are just more consumption choices that one picks from the list of downloadable apps.

The Personal Democracy Forum is a fascinating event. It is filled with intelligent individuals who speak of democracy with unimpeachable sincerity, and activists who really have been able to use the Internet to advance their causes. But despite all of this, the ideological emphasis on “the tech we need” remains based upon a quizzical notion of “need,” a problematic concept of “we,” and a reductive definition of “tech.” For statements like “the tech we need” are not value neutral – and even if the surface ethics are moving and inspirational, sometimes a problematic ideology is most easily disseminated when it takes care to dispense with ideologues. And though the New York Ideology is much more subtle than the Californian Ideology – and makes space for some critical voices – it remains a vehicle for disseminating an optimistic faith that a technologically enhanced Moses shall lead us into the high-tech promised land.

The 2016 Personal Democracy Forum put forth an inspirational and moving vision of “the tech we need.”

But when it comes to promises of technological salvation, isn’t it about time that “we” stopped getting our hopes up?

Coda

I confess, I am hardly free of my own ideological biases. And I recognize that everything written here may simply be dismissed of by those who find it hypocritical that I composed such remarks on a computer and then posted them online. But I would say that the more we find ourselves using technology the more careful we must be that we do not allow ourselves to be used by that technology.

And thus, I shall simply conclude by once more citing a dead, but prescient, pessimist:

I have no illusions that my arguments will convince anyone. (Ellul 1994, 248)

_____

Zachary Loeb is a writer, activist, librarian, and terrible accordion player. He earned his MSIS from the University of Texas at Austin, an MA from the Media, Culture, and Communications department at NYU, and is currently working towards a PhD in the History and Sociology of Science department at the University of Pennsylvania. His research areas include media refusal and resistance to technology, ideologies that develop in response to technological change, and the ways in which technology factors into ethical philosophy – particularly in regards of the way in which Jewish philosophers have written about ethics and technology. Using the moniker “The Luddbrarian,” Loeb writes at the blog Librarian Shipwreck, where an earlier version of this post first appeared, and is a frequent contributor to The b2 Review Digital Studies section.

Back to the essay

_____

Works Cited

- Barbrook, Richard and Andy Cameron. 2001. “The Californian Ideology.” In Peter Ludlow, ed., Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates and Pirate Utopias. Cambridge: MIT Press. 363-387.

- Ellul, Jacques. 2004. The Political Illusion. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock.

- Ellul, Jacques. 1994. A Critique of the New Commonplaces. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock.

- Green, Archie, David Roediger, Franklin Rosemont, and Salvatore Salerno. 2016. The Big Red Songbook: 250+ IWW Songs! Oakland, CA: PM Press.

- Illich, Ivan. 1973. Tools for Conviviality. New York: Harper and Row.

- Marvin, Carolyn. 1988. When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking About Electric Communication in the Late Nineteenth Century. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Marx, Leo. 1997. “‘Technology’: The Emergence of a Hazardous Concept.” Social Research 64:3 (Fall). 965-988.

- Mumford, Lewis. 1964. “Authoritarian and Democratic Technics.” in Technology and Culture, 5:1 (Winter). 1-8.

- Weil, Simone. 2010. The Need for Roots. London: Routledge.

As this poetic quote by Sarah Josepha Hale, nineteenth-century author and influential editor reminds us, context is everything. The challenge, if we wish to write women back into history via Wikipedia, is to figure out how to shift the frame of references so that our stars can shine, since the problem of who precisely is “worthy of commemoration” or in Wikipedia language, who is deemed

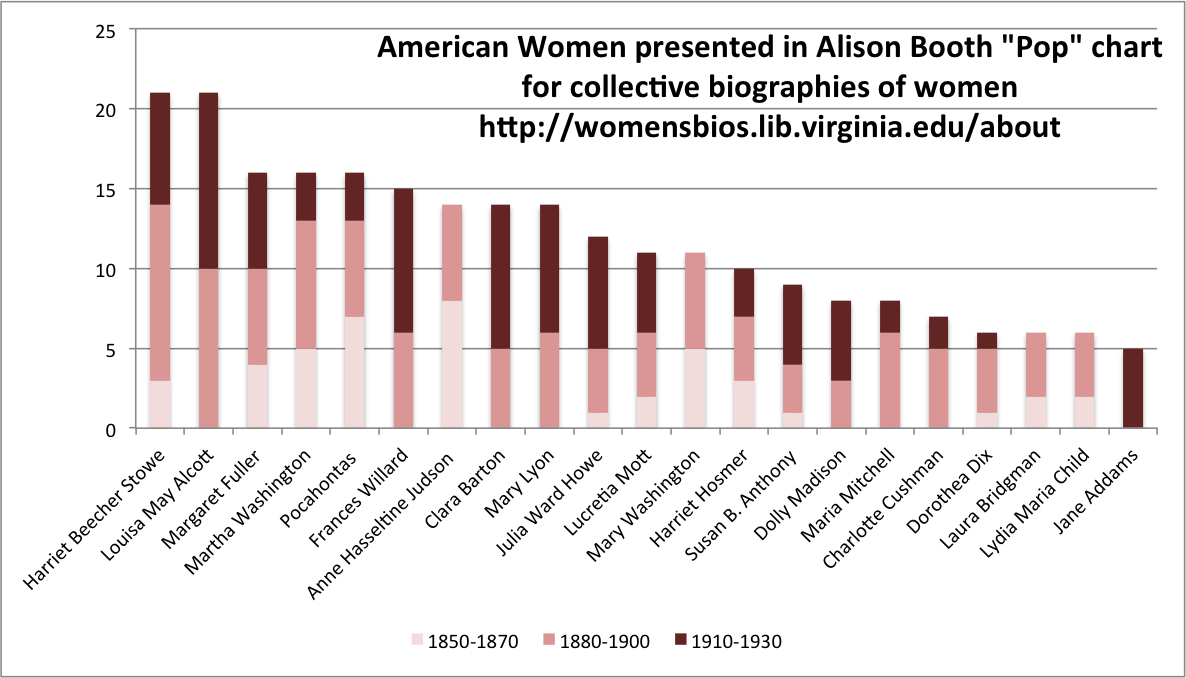

As this poetic quote by Sarah Josepha Hale, nineteenth-century author and influential editor reminds us, context is everything. The challenge, if we wish to write women back into history via Wikipedia, is to figure out how to shift the frame of references so that our stars can shine, since the problem of who precisely is “worthy of commemoration” or in Wikipedia language, who is deemed  mes of prosopography published during what might be termed the heyday of the genre, 1830-1940, when the rise of the middle class and increased literacy combined with relatively cheap production of books to make such volumes both practicable and popular. Booth also points out, that lest we consign the genre to the realm of mere curiosity, predating the invention of “women’s history” the compilers, editrixes or authors of these volumes considered them a contribution to “national history” and indeed Booth concludes that the volumes were “indispensable aids in the formation of nationhood.”

mes of prosopography published during what might be termed the heyday of the genre, 1830-1940, when the rise of the middle class and increased literacy combined with relatively cheap production of books to make such volumes both practicable and popular. Booth also points out, that lest we consign the genre to the realm of mere curiosity, predating the invention of “women’s history” the compilers, editrixes or authors of these volumes considered them a contribution to “national history” and indeed Booth concludes that the volumes were “indispensable aids in the formation of nationhood.”