The Prodigal Political Emerson

by Sarah Blythe

~

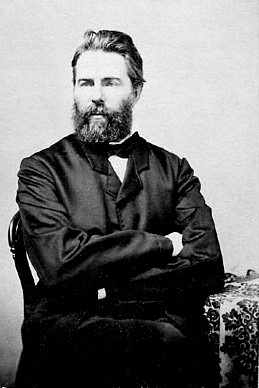

Much like the other volumes in the series, the chief aim of A Political Companion to Emerson is to challenge the notion that a particular author is much more politically minded than past scholarship has allowed. Ralph Waldo Emerson was no stranger to such censure, even within his own lifetime. The most biting assessment comes from fellow author, Rebecca Harding Davis, who reflected on her interactions with Emerson and his “Atlantic coterie” in her 1904 cultural memoir, Bits of Gossip. She describes the coterie as thinking “they were guiding the real world,” while in fact “they stood quite outside of it, and never would see what it was.”1 Of Emerson as an individual, she had only this chilly assessment: “He took from each man his drop of stored honey, and after that the man counted for no more to him than any other robbed bee.”2 This version of Emerson—the alienated dreamer, or worse, the intellectual vampire—is certainly unfair but not altogether groundless. Some of Emerson’s writings can be off-putting at times, especially when taken out of context. Most famously, in Emerson’s hymn to nonconformity—“Self-Reliance”—the transcendentalist professes such a radical disavowal of social obligations in pursuit of genius that his individualism seemingly transforms into something akin to an unfeeling libertarianism. He first proclaims he will “shun father and mother and wife and brother” when his genius calls, writing on “the lintels of the door-post, Whim,” and in the next breath flippantly disregards his obligation to the poor: “Are they my poor?”3 But to suggest that Emerson is simply coldly rejecting his social obligations or taking an apolitical stance is to willfully misunderstand him.

The primary achievement of A Political Companion to Emerson, then, is in righting this complicated, and oft-skewed version of the famous transcendentalist. As several of the critics in this volume point out, Emerson is posturing here. He aims for shock in his attack on “the thousandfold Relief Societies” that merely conform instead of reform and thus offer relief to no one.4 Ever the “reluctant reformer” (as Lawrence Buell terms him in his recent biography), this younger, 3more idealistic Emerson ultimately confirms his commitment to self-reliance even when faced with the pragmatic realities of slavery and other social injustices later in life.5 It is only after his death that Emerson became increasingly estranged from these moments of political activism. Defanged of his radical politics and abolitionist stance beginning with Holmes’s and Cabot’s biographies in the 1880s, this depoliticized version of Emerson was perpetuated by critics through the 1980s, who tended to emphasize his passive self-reliant (and apolitical) individualism, as volume editors Alan M. Levine and Daniel S. Malachuk highlight in their lengthy introduction (16-17). Within this context, Emerson is a prime candidate for sustained political study, the first of its kind in Emerson studies.

Youthful scholars more familiar with Emerson criticism of the last twenty years will be surprised that he was ever so roughly handled by late-nineteenth- and earlier twentieth century Emerson scholars. It may seem strange to image an author, who wrote so movingly about abolition, de-politicized first by his contemporaries and later by the academy. Some readers might even question the value of pushing against such fossilized scholarship. However, working through A Political Companion to Ralph Waldo Emerson, from its “classic” re-readings of Emerson’s political mind from the 1990s through more current twenty-first century scholarship, readers will perceive not just a dynamic picture of the famous transcendentalist’s political mind, but also a multi-vocal intellectual history of political scholarship on Emerson. As a political companion, the collection sketches the complicated and sometimes contradictory development of Emerson’s political thinking as much as the complicated and contradictory development of scholarly uses of Emerson’s political thinking. Dissonant and melodious, frustrating and engaging, the authors and texts thankfully do not present an explicit or clear picture of Emerson’s politics; but nor should they. The selected authors instead rub up against each other, praising and censuring accordingly, but never quite coming to consensus, forming the kind of dissensus that Emerson would heartily approve.

A substantial volume (thirteen essays in all), the book is divided into four sections beginning with four “classic” texts on Emerson by notable political theorists and philosophers: William Carey McWilliams, Judith Shklar, George Kateb and Stanely Cavell. In choosing a chapter from McWilliams’s formidable 1973 study of national manhood, The Idea of Fraternity in America, to begin their collection, Levine and Malachuk forward a version (albeit mild) of the apolitical Emerson the volume is designed to contradict. But this is done to effect. McWilliams argues that Emerson wasn’t so much an apolitical thinker but a political idealist who believed that human progress would eventually abolish slavery and the United States would become a “political brotherhood.” For McWilliams, Emerson “firmly believed that progress did not require a movement; it was written in the motion of nature, and would come of itself” (46). Because the political brotherhood was inevitable, Emerson was able to eschew politics, McWilliams maintains. While McWilliams briefly concedes that Emerson’s rhetorical use of fraternity has allowed numerous critics to cast Emerson as a philosopher of democracy, he ultimately concludes that, “Emerson’s was a doctrine of activity, individualistic romanticism, not democracy” (48-9). Emerson, then, is not a champion of democracy but of individualism in such a reading. McWilliams’s essay may seem out of place given the aim of this volume, but it represents an important shift from previous attacks on Emerson’s self-reliant individualism: McWilliams does not completely depoliticize Emerson but instead makes him politically passive. It is this version of Emerson’s political passivism that later essays in this volume vividly confront.

The second “classic” text by Judith Shklar likewise reconsiders the notion that Emerson’s individualism was at odds with democracy. Where McWilliams sees in Emersonian thinking a call for a progressive political brotherhood, Shklar finds reconciliation between democracy and individualism in Emerson’s skepticism. Focusing on Representative Men and “Self-Reliance,” Shklar suggests that skepticism and democracy were joined in Emerson’s mind because individuals participating in a democracy necessarily have doubts about the opinions of fellow citizens (65-66). But Emerson’s purpose in writing Representative Men is not merely to praise Montaigne’s skepticism, Shklar maintains, but to demonstrate the “absolute necessity of great men for revealing the possibilities of reason, imagination, discovery, and beauty” without “begrudging the great men their glory, not because he was small minded but because an uncritical belief in great people was not compatible with his democratic convictions” (59). Because Emerson thought we were all reformers, there must be doubts, Shklar ultimately insists.

Shklar’s essay is in many ways a platform for her working out of her own political theory to contend with the current problems of American democracy and has been used as such by fellow political theorists. Shklar finds redemption in political skepticism. In this sense, the editors might have been better served using Sacvan Bercovitch’s “Emerson, Individualism, and the Ambiguities of Dissent” (published in 1990) in the South Atlantic Quarterly instead of Shklar’s more politically provocative piece. Bercovitch’s essay comes to roughly the same conclusion—finding in Emersonian thinking a space for dissent within a democratic consensus—and has had a greater impact on American literary studies than Shklar’s treatise.

The final two authors in this first section—Cavell and Kateb—are most aptly selected. In Buell’s fitting assessment, “No one has written more searchingly about Emerson’s theory of self-reliance than George Kateb.”6 As the essay selected for this volume demonstrates, Kateb has come to understand Emerson’s self-reliance as promoting an individualism that works within instead of against democracy. Emerson’s problem with democracy, as Kateb notes, is that it requires “association,” which has the potential to disturb self-reliance. But since Emerson calls for self-reform in his self-reliance, Kateb finds in Emerson a means to defend the individual against institutional regulation. Elsewhere Kateb calls this means “negative individuality,” or the kind of character that disobeys unjust conventions and laws.7 The resulting struggle for self-reliance, in Kateb’s estimation, “is a struggle against being used” (87). Stanley Cavell is also invested in the philosophical matter of instrumentalism, but he finds a more suitable answer in Emerson’s skepticism or his “averse thinking” as the title suggests, connecting Emerson directly to the philosophy of Heidegger and Nietzsche. That said, much like Shklar’s skepticism, Cavell’s “averse thinking” has had more impact in philosophy and political theory than Emerson studies or the study of American literature but it is a worthy inclusion none-the-less.

Part 2 of this volume is ambiguously titled “Emerson’s Self-Reliance Properly Understood,” but it might be better identified as “Emerson’s Self-Reliance and the Politics of Slavery.” The three essays contained in it look more carefully at Emerson’s self-reliance in the context of a democracy that suffers slavery, arguably the most troubling aspect of Emerson’s writings. Jack Turner, James H. Read, and to a lesser extent Len Gougeon, each explore Emerson’s philosophy of self-reliance in conjunction with slavery and social reform. Both Turner and Read call attention to Emerson’s increasingly public abolitionist stance beginning with the passing of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 precisely because it made him and every other northern explicitly complicit to slavery, an institution which likewise denied slave and master the ability to realize self-reliance.

~

Dissonant and melodious, frustrating and engaging, the authors and texts thankfully do not present an explicit or clear picture of Emerson’s politics; but nor should they.

~

In Turner’s careful reading of Emerson’s “ethics of citizenship,” he discerns a “complex interplay” of two key ideas: self-reliance and complicity (126-7). While Turner is attentive to the fact that Emerson never addressed these two terms directly (complicity and self-reliance), he finds in Emerson’s antislavery writings and his abolitionist activities a clear demonstration of his (Emerson’s) belief in their incompatibility, for complicity is just another name for conformity. Turner is likewise careful to not exaggerate Emerson’s activism, noting that he was reluctant to speak out about slavery until the Fugitive Slave Law required more action of him. In the end, Turner finds in Emerson’s ethics of citizenship “a politics of self-reliance that allows for moral compromise” and “a promising model for meeting the contemporary challenge of civic engagement (142).

Moving from Turner’s ethics of citizenship, Gougen and Read focus on the complicating factors informing Emerson’s self-reliance as well as his changing relation to the abolition movement as new laws began to force citizens into conformity and complicity with the institution of slavery. Clearly the traumatic events of the mid-nineteenth century troubled Emerson’s definition of self-reliance. Emerson responded, Read claims, by embracing John Brown and his radical politics and speaking out against slavery more vociferously. Both acts are deeply political for Read: speaking out against slavery in antebellum America was tantamount to taking action against it (162). In this context, Emerson’s self-reliance becomes a model for moral compromise and a means of taking action against slavery “without along the way compromising or suffocating one’s own intellectual and practical self-reliance” (153). But most importantly, Read contributes a picture of Emerson as a growing intellectual mind who recognized the limits of his self-reliant philosophy later in life and strove to reconcile these limits in a democracy that denied self-reliance to slave and master alike. Along these lines, Gougeon looks beyond Emerson’s self-reliant treatise to see how Emerson used his transcendental philosophy in the service of social reform. This philosophy allows for every person (regardless of race) to participate in the universal (the “Over-Soul”) “providing the basis for both individual self-reliance and a collective identity” (186). For Gougeon, Emersonian social reform may begin with the individual, but it does not end there; self-reform leads to social reform. And, like Read and Turner, Gougeon also highlights Emerson’s evolving transcendental thinking, demonstrating a commitment to “rotation” and “becoming.”

Part 3 of the collection is dedicated to probing Emerson’s transcendental philosophy in an effort to recover Emerson’s transcendentalism without setting it apart from his political philosophy. As numerous critics in this volume note, Emerson has been as much denuded of his transcendental philosophy as his political philosophy. The essays put forward in this section, then, “retranscendentalize” Emerson whilst they repoliticize his thinking, locating in Emersonian transcendentalism no opposition to political engagement. Alan M. Levine grapples with Emerson’s skepticism, concluding that Emerson’s doubt was fundamental to his transcendental beliefs, while Daniel S. Malachuk battles past scholarship that has effectively detranscendentalized Emerson, obscuring the commitment to equality in his transcendental thinking. Finally, Shannon L. Mariotti examines Emerson’s metaphors of vision, questioning his ability to see problems clearly with transcendental sight. Noting a change in his thinking around 1844, Mariotti concludes that Emerson came to question the validity of his transcendental vision, ultimately finding a middle ground in his transcendental visual practice of “focal distancing.” Mariotti’s essay ultimately explores a version of Emersonian political theory that reconciles his transcendental idealism with the practicalities of social reform.

The fourth and final section is also the most knotty, designed to cast Emerson as a devout liberal (or progressive) democrat. While Emerson’s progressive democratic leanings are undeniable (Buell goes so far as to claim Emerson personified the Union ideal for moderates as well as progressives during the Civil War), the three contributors concluding this volume emphasize (or perhaps over-emphasize) certain aspects of liberal democracy said to be embraced by Emerson.8

Neal Dolan’s recent account of Emerson’s theories of commerce aims to reinterpret our understanding of his vision of liberal democracy. In doing so, Dolan offers a new interpretation of Emerson’s use of the language of ownership, commerce, and property. At once muddled and overly rigid, Dolan’s argument maintains that Emerson uses the language of property and commerce to “symbolically resolve a cultural dilemma” between old world economics and new world economics (344). For Dolan, Emerson championed America’s liberal democratic values against European feudal-aristocratic social systems on the one hand; on the other, he was weary of the American tendency to “reduce all relationships to marketplace calculations” (344). Dolan concludes that “Emerson inflected this economic idiom in distinctive ways in an attempt to raise his audiences understanding of their rightful property, and thus of their rightful selves, to a yet higher, more spiritual, and more ecstatic plane” (345). However, in interpreting Emerson’s economic idioms within the context of “Puritanism, the Scottish Enlightenment, and the full emergence of a market economy in antebellum America,” Dolan strips Emerson (and his contemporary transcendentalists) of his more radical politics in order to frame the transcendentalist as a pro-capitalist liberal democrat (345). This version of Emerson is not only unpalatable but also largely incorrect. One must remember that Emerson rubbed elbows with Orestes Brownson, who espoused a brand of socialism in the 1830s that Marx would make famous a decade later. This is not to suggest that Emerson was as radical a socialist as Marx or even Brownson (no need to rush-order your Che Emerson t-shirts), but I would challenge Dolan’s assertion that Emerson was “pro-market” during his “supposedly radical phase” in both action and thought (361). As evidence for this claim, Dolan first points out that Emerson “participated” in market-capitalism to the extent that he marketed himself (the action). He then offers a problematic reading of a passage from “Politics,” in which Emerson makes the outrageous assertion that “while the rights of all as persons are equal…their rights in Property are very unequal” (the thought). If taken at face value, this evidence is indeed damning, but here Dolan fails to recognize Emerson’s posturing as a mechanism for criticizing a political system of which he was often skeptical.

In contrast to Dolan’s interest in property, Jason Frank probes Emerson’s understanding of representation and representativeness in order to demonstrate the democratic importance the “representative man.” For Frank, Emerson’s representative men are not departures from his philosophy of self-reliance because “they elicit the transformative capacities of democratic constituencies forever in the midst of a process” (385). Because there is a distinct relational dynamic between the representative and the represented according to Frank, “this relation stimulates perfectionist transformation” not at odds with Emerson’s theory of self-reliance. The final essay by G. Borden Flannigan likewise reassesses Emerson’s commitment to excellence in the face of liberal democracy in “Representative Men,” but does so by stressing his debt to Plato and Aristotle.

In reading this collection of essays one gets the sense that Emerson was not an explicitly political thinker; nor was he an explicitly apolitical thinker. He might be best represented as an evocative thinker, a philosopher (often a political philosopher), a humanist, and of course a transcendentalist. He thought carefully and “becomingly” (in an Emersonian sense) about the world in which he inhabited. It is therefore difficult to locate his philosophy—political or otherwise—in just one text or at just one moment in his life. When Emerson wrote, “rotation is the law of nature” in Representative Men, he is not dwelling on physical laws of change; his meaning is social and political, suggesting process, progress, and most importantly change over time on a personal level as much as a national level. And since we now readily accept that personal is political, this volume, along with this series, reminds us never to regard any thinker as wholly removed from the political sphere.

__________

Sarah Blythe is a PhD Candidate in the Department of English at UNC Chapel Hill. Tentatively titled “Juicy Effects,” her doctoral dissertation examines the excessive florid and floral rhetoric populating the American short story in the decades straddling the Civil War.

__________

Notes

1. Davis, Rebecca Harding. Bits of Gossip. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1904. 33.

Back to essay

2. Ibid. 46.

Back to essay

3. Emerson, R.W. “Self-Reliance.”

Back to essay

4. Ibid.

Back to essay

5. Buell, Laurence. Emerson. Cambridge; Harvard UP, 2004.

Back to essay

6. Ibid. 158.

Back to essay

7. Kateb, George. The Inner Ocean: Individualism and Democratic Culture. Ithica: Cornell UP, 1992.

Back to essay

8. Buell. Op. Cit. 206.

Back to essay