by Ann Cvetkovich, University of Texas at Austin

~

In the wake of José’s death, many people have invoked passages from Cruising Utopia in order to express the significance of his work and what he meant to them. His call to “hear something else” and “feel something else” in the “then and there of queer futurity” has been a form of solace, as though we might be able to feel him while “cruising utopia.” Although I too feel that call, my thoughts have turned more to the book he hadn’t yet published, which was once called Feeling Brown but which morphed over time to become The Sense of Brown. I’ve been waiting for the book at least as far back as the essay called “Feeling Brown,” about Ricardo Bracho’s The Sweetest Hangover, which was published in 2000. It is an article to which I returned again and again to ponder José’s ambitious aim of “describing how race and ethnicity are to be understood as “affective difference.” By affective difference I mean the ways in which different historically coherent groups “feel” differently and navigate the material world on a different emotional register” (70). I found these sentences so thrilling for what they meant about the promise of the affective turn.

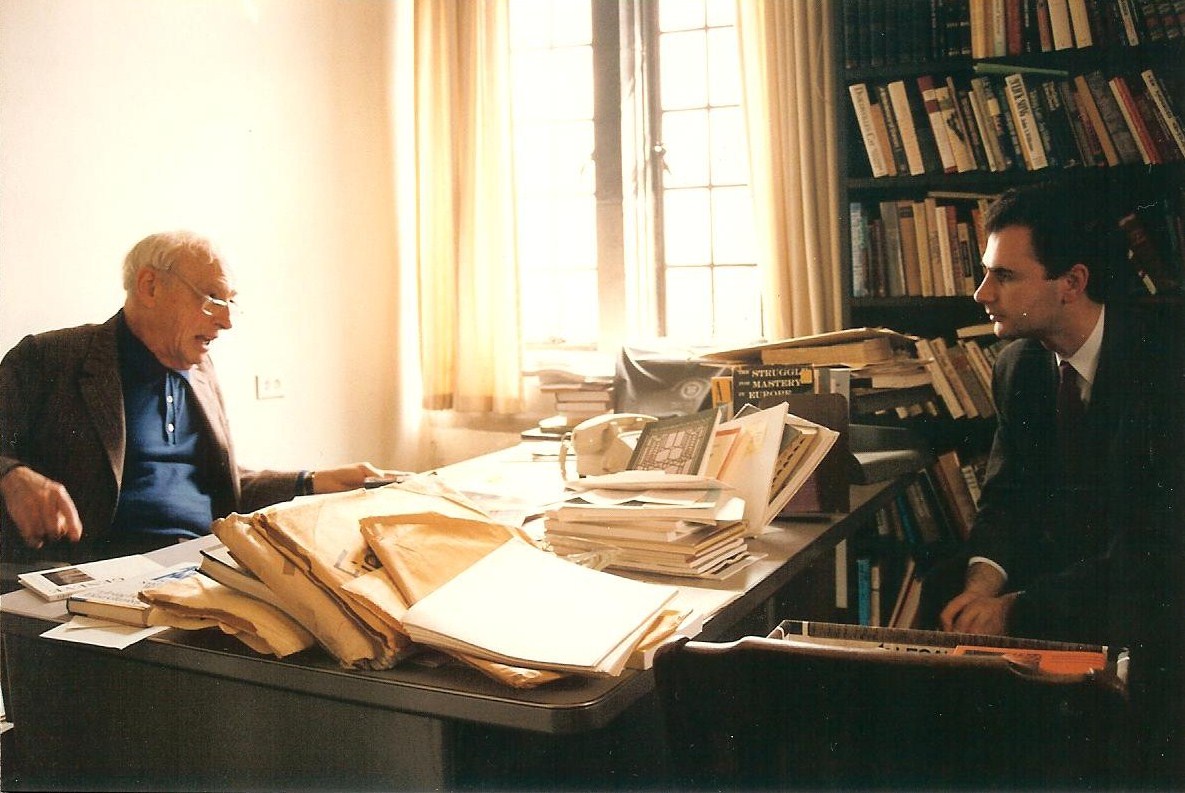

But it took a while before I was able look back to those old publications. When José first died, I just wanted to think about him as a friend not a colleague. It was too heartbreaking to acknowledge how much I will miss the live encounters with his thinking and how much I have come to depend on learning about his ideas in conversations about work in progress—from queer faculty working groups years ago at NYU, to Public Feelings events, to a salon about the good life in my living room last year. When I was finally able to turn to his writing, one of the first things I reached for was the work that I taught most recently—“Feeling Brown, Feeling Down,” his essay about Nao Bustamante’s Neapolitan and Melanie Klein’s depressive position. I had assigned it for my spring 2013 graduate seminar on “Queer Affect, Queer Archives,” and the students wanted to return to it at the end of the semester because we hadn’t had enough time to cover it the first time around. My files thus contain two sets of notes, which makes it easier to see which points seemed most important. What follows are some of the things that stood out then and that I find myself wanting to remember and pass on now.

First and foremost is this more recent essay’s articulation of the turn away from identity and towards affect in order to describe brown as a “feeling,” including the brilliant rephrasing of Gayatri Spivak to yield the compelling question, “How does the subaltern feel?” I quote at some length in order to provide the context:

My endeavor, more descriptively, is intended to enable a project that imagines a position or narrative of being and becoming that can resist the pull of identitarian models of relationality. Affect is not meant to be a simple placeholder for identity in my work. Indeed, it is supposed to be something altogether different; it is, instead, supposed to be descriptive of the receptors we use to hear each other and the frequencies on which certain subalterns speak and are heard or, more importantly, felt. This leaves us to amend Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s famous quotation, “Can the subaltern speak?” (1988, 1999) to ask How does the subaltern feel? How might subalterns feel each other? (677)

I love the modification of Spivak’s question because the original has been crucial to my own intellectual formation, and the revised version echoes a question that has driven my research, “How does capitalism feel?” José’s questions not only signal the affective turn but affirm the use of the vernacular word “feel” as a theoretical term. Even as he is gearing up to explain how Kleinian object-relations theory and the depressive position have something to offer, he signals the value of ordinary feelings and lived experience as a foundation for thinking, as in: “Describing the depressive position in relation to what I am calling “brown feeling” chronicles a certain ethics of the self that is utilized and deployed by people of color and other minoritarian subjects who don’t feel quite right [my emphasis] within the protocols of normative affect and comportment” (676). For those who often “don’t feel quite right,” this is profoundly enabling work.

Also apparent in the longer passage quoted above is the conceptual challenge of the turn from identity to affect, evident in the rhetorical gestures that underscore this move–the insistence that affect is not a mere “placeholder” and the stated desire that it “be something altogether different.” As a reader, I lean in closely for the next sentence where José mentions the “receptors” and “frequencies” that allow us (or “certain subalterns”) to hear and feel each other. I love this sense of “tuning in” to something that can’t fully be felt, and I want to hear more about the notion of “racialized attentiveness” (680), which constitutes not only a method but a way of living or a structure of feeling. A close reading of this vocabulary of attention helps explain why José might have moved from “feeling” to “sense” as a keyword or critical concept, as he developed a language for tracking the subtle mechanisms by which queers of color or “minoritarian subjects” find and connect with one another.

José’s distinctive mix of high and low archives, including his range of theoretical sources, constitutes a queer method or, as he puts it, “the stitching I am doing between critical race theories, queer critique, and psychological object-relations theory” in order to produce a “weak” and/or reparative theory. Here as elsewhere, his work is also distinguished by his commitment to a canon of white Marxist and European theory and his ability, often through disidentification, to put what might seem like unlikely sources to service in thinking about queers of color. Through “stitching” together somewhat unlikely companions, and a willingness to let the seams show, he avoids the “cryptouniversalism” (688) of those who are too faithful or narrow in their theoretical allegiances. One of the reasons I am so upset to lose him is because we need “brown feelings” if affect theory, including its queer versions, is not to become too white. His insistence that the affective turn be about race needs to be carried forward.

José also staged encounters between different bodies of theory by working closely with queer of color artists, who produce theory in a different register. In “Feeling Brown, Feeling Down,” he turns to Nao Bustamante, one of the fellow travelers with whom he had a long connection and through whose work and friendship his projects were conceived. In his analysis of Nao’s tears and her literal use of stitching in Neapolitan’s crocheted video installation, he offers an account of “the depressive position” as a historically specific form of racialized affect. He invites us to hear the “sound of brown feelings” in the work’s soundtrack and to appreciate the outlandishness of the “sad crow of depression” perched on top of the TV monitor that features Nao’s crying face. And he gently but firmly admonishes those who would mistake this particularity for something either stereotypically Mexican or universally human. It is poignant to read this account now in retrospect and to hope for the reparative potential of tears.

As I turned reluctantly to the necessity of now meeting with José through writing rather than in person, one of the things my archive yielded was the original book proposal for Feeling Brown. I have one version that we discussed in the NYU Queer Faculty Working Group, likely sometime in 1999-2000, and another version that I read for Duke UP in 2000 so that he could get an advance contract. I was surprised to remember how long ago the proposal had been written; José had just barely published Disidentifications, and he already had a robust second book project. I think it was useful for him to publish Cruising Utopia first; because The Sense of Brown was so ambitious, it benefited from continuing to evolve over time. In the interim, affect theory exploded and morphed in no small part as a result of José’s own work, including the Women and Performance special issue he edited, which stakes out the relations between affect theory and psychoanalysis, the essay on Ana Mendieta in which he more directly addresses sense over feeling, or the talk he had been giving over the last year on Wu Tsang’s documentary film Wildness, in which he was developing his notion of a “brown commons.”

But even in this early version of the project, the key point that race is experienced as a feeling is already present. In both versions, I circled the sentences (quoted in my initial paragraph) that also appear in the Ricardo Bracho essay. My notes show excited questions that would prove generative for me and so many others — about national affect, about the relation between Marxism and psychoanalysis, and about the use of Williams and DuBois as sources for affect theory. Queer affect theory was still emerging at that point, and although we would come to fuller set of tools, José, who had a head start as Eve Sedgwick’s student, was inventing something very rich in order to make good on his vision of “a radical reconceptualization of ethnicity as affective specificity.” I will continue to tune in to his work to “feel something else” — including “the sense of brown.”1

_____

Visit the full José Esteban Muñoz gallery here.

_____

Notes

1. The phrases “hear something else” and “feel something else” are underscored in Kay Turner’s song “Cruising Utopia,” the lyrics for which are taken from José’s book and originally performed at “Otherwise: Queer Scholarship into Song,” Dixon Place, April 4, 2013 and subsequently at memorials for him in New York.

Back to essay

Works Cited

José Esteban Muñoz, “Feeling Brown: Ethnicity and Affect in Ricardo Bracho’s The Sweetest Hangover (and other STDs).” Theatre Journal 52:1 (2000): 67-79.

—–, “Feeling Brown, Feeling Down: Latina Affect, the Performativity of Race, and the Depressive Position.” Signs 31:3 (2006): 675-688.