The lecture below was initially presented at the “Algorithms, Infrastructures, Art, Curation” conference, organized by Arne De Boever and Dany Naierman, and hosted by the MA Aesthetics and Politics program (School of Critical Studies, California Institute of the Arts) and the West Hollywood Public Library. The lecture is published here as part of a dossier including Stephen Wright’s response to the lecture.

All images included in the lecture are from the slideshow that Brian Holmes delivered at the lecture. The slide called “Information’s Metropolis” includes images by Beate Geissler and Oliver Sann.

–Arne De Boever

by Brian Holmes

Can a device create a world? Can it destroy one? Are these still the right questions to be asking?

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis I carried out two parallel research programs. They dealt with container ports, on the one hand, and financial algorithms, on the other. Both projects began with essays about socio-technical apparatuses or devices, in the sense of the French word dispositif.[1] Both explored the role of these devices in contemporary world-making. Both grew into localized artistic collaborations with experiential and documentary dimensions. I want to share these experiences, to talk about the creation and the destruction of the neoliberal world. The aim is to answer the question, “What comes after neoliberalism?” But the results of the inquiry showed that if globalism is ever to end, the question has to be asked in a regional frame. So I will be talking about what comes after Chimerica.

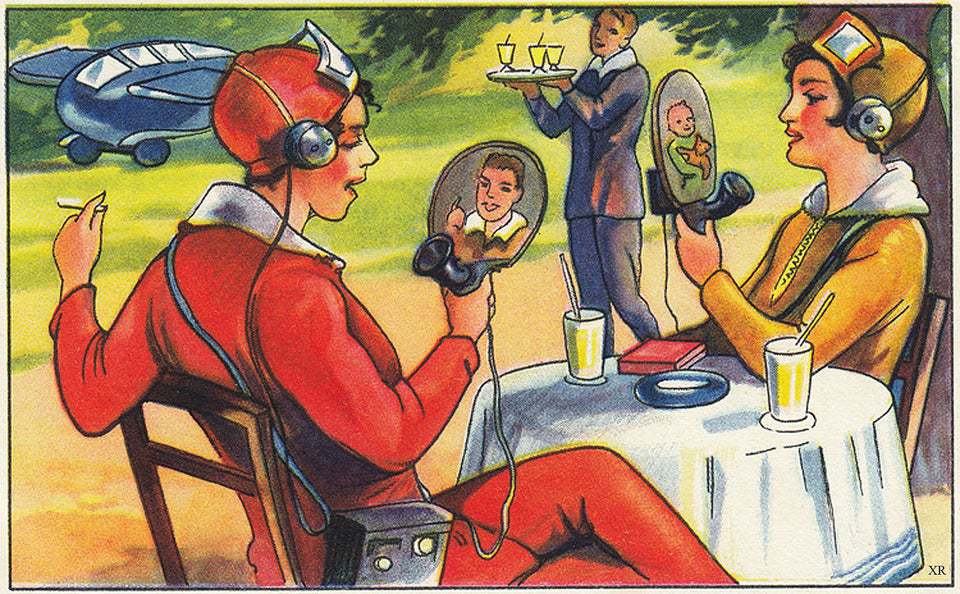

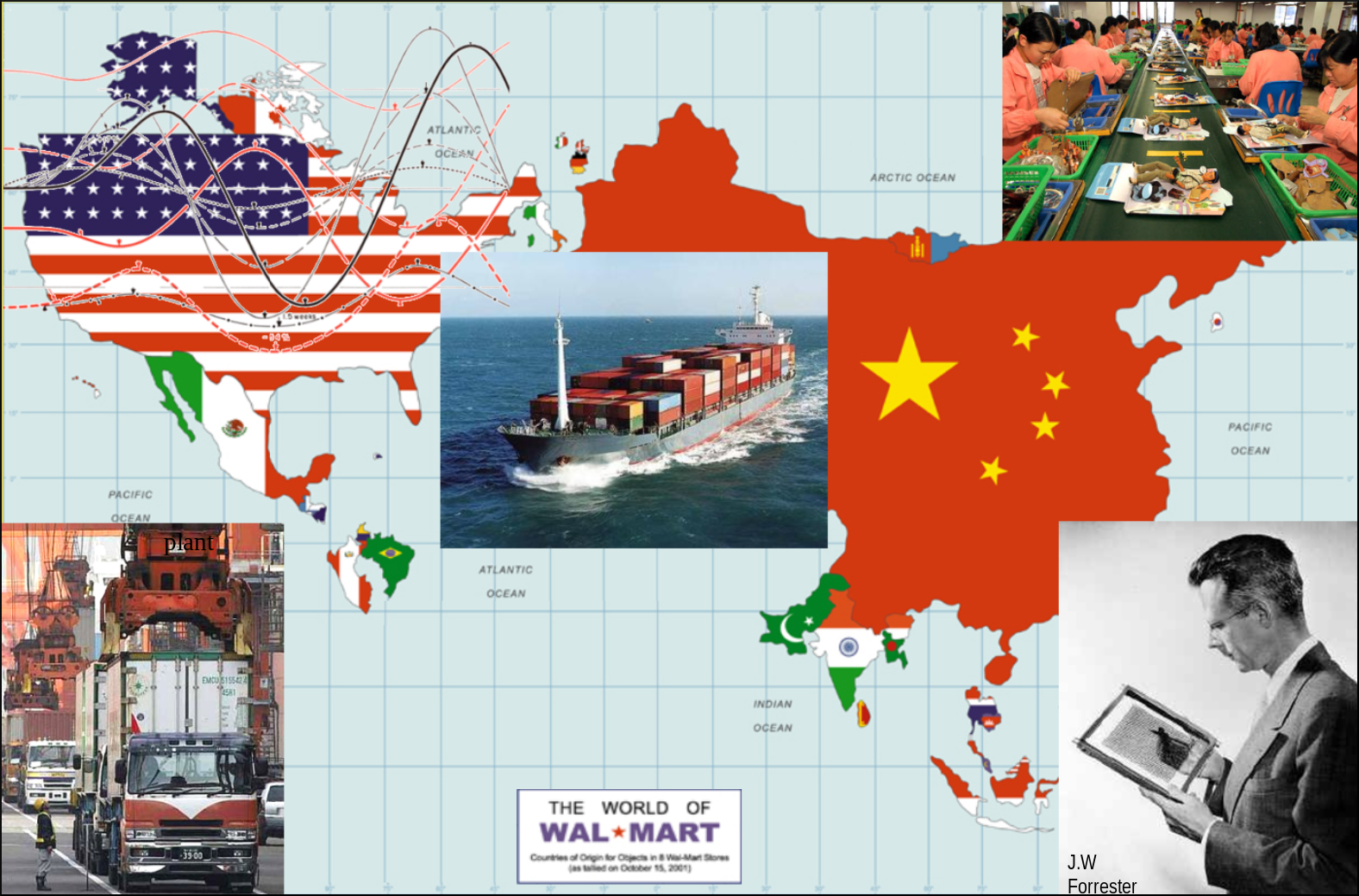

The first investigation was launched with a theoretical essay entitled “Do Containers Dream of Electric People?”[2] That text retraced the historical process whereby the invention of the shipping container intersected with the upsurge of manufacturing in Asia, to create the new economic paradigm of just-in-time production and distribution, coordinated across the world by networked logistics. I explored the roots of contemporary logistics in the cybernetic engineering of a man named Jay Wright Forrester; yet history was not the main point of this work. To get into “the social form of just-in-time production” as it is today, I followed the artist and activist Rozalinda Borcila on the exploration of a series of intermodal railyards located along a centuries-old transportation corridor heading southwest out of Chicago. The title for our shared project was Southwest Corridor Northwest Passage, because we realized that the old colonial dream of a frictionless passage across North America had been fulfilled by the container connection to Asia.[3]

We were galvanized by a precarious workers’ strike at a pair of gigantic warehouses out on the far end of that historical corridor. We wanted to know how the warehouses, the Wal-Marts they supplied and the abysmal wages they paid were related to the nearby railyards, the containers they handled and the distant ports from which the commodities came. An extremely simple device served to focus our thoughts, namely the twist lock, which binds containers together on a ship, a truck, or a railroad car. We wanted to show people, as concretely as possible, how the larger architecture of containerized commodity transport binds our daily lives in Chicago to the manufacturing centers of Asia, via the transcontinental rail links of the BNSF and Union Pacific lines, plus the deepwater ports of Los Angeles/Long Beach. It was about the social tie in motion. We were saying that each twist of that locking device serves to create and maintain the dynamic structure of the neoliberal world.

Much of our art exhibition involved taking people on walks to historical and contemporary sites along the Southwest Corridor. But the associated research extended far beyond Chicago, to Kansas City, to the deepwater port of Lázaro Cardenas in southern Mexico, and to the Panama Canal. Ultimately, for reasons a bit too complicated to explain, I found myself in South Korea with the artist Steve Rowell, exploring the huge intermodal ports of Busan, which function as hubs linking long-haul freighters to smaller ships serving dozens of industrial centers in Japan, China and the rest of Asia. After getting our fill of ocean-going boats and big steel boxes swinging through the air, we drove over a series of gleaming bridges and fenced-off causeways to squint through the rain at the Triple-E class container ships being built by the Daewoo conglomerate for the big European cargo handler, Moller-Maersk. When you see the scale of these operations in Asia, and when you breathe the pollution they release, then you can really feel how we’ve been locked into climate change, which is now opening a literal Northwest Passage through the melting ice of the Arctic.

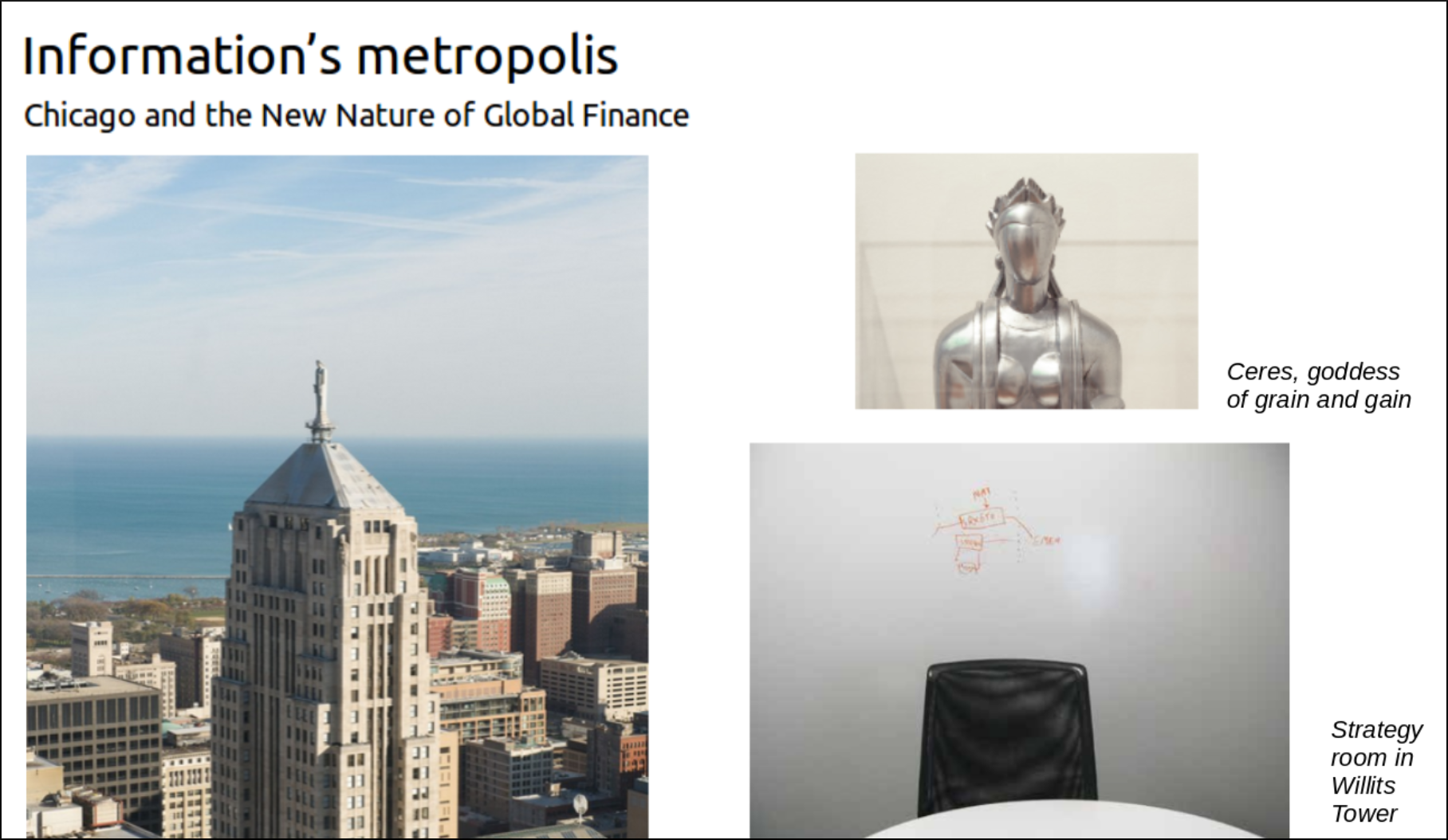

The second research process began with another essay: “Is It Written in the Stars?”[4] This text used an artwork called Black Shoals Stock Market Planetarium, by Lise Autogena and Joshua Portway, as a way to understand how financial derivatives shape human destinies. The investigation turned into a documentary project with the Chicago-based photographers Geissler and Sann, leading to a book entitled Volatile Smile.[5] The idea was to bring together three series of images: one showing innumerable Chicago-area homes and apartments left empty by the 2008 real-estate crisis; the second showing the empty desks of algo-traders on a trading floor inside Willis Tower; and the third, a series of portraits showing the strange rictus of satisfaction and exultant pleasure that momentarily appears on the lips of video-gamers in first-person shooter contests, at the moment of the fictional kill. Could we make the case that an agent (the traders) and an instrument (the algorithms) had given rise to the vast material despoilment of the housing crisis?

In the essay for the book, entitled “Information’s Metropolis,” I argued that what Geissler and Sann’s work depicted was a global social relation that had emerged from the use of computerized trading strategies on Chicago’s futures and options markets.[6] In other words, our shared world is constituted by “capitalism with derivatives.”[7] To make the case I retraced the process whereby a new generation of Chicago traders encountered a mathematical device known as the Black-Scholes formula, used for the pricing of options. The equation brings together all the variables involved in the sale of an option to buy a stock for a fixed price at a future date. By making these variables calculable, the formula allows the trader who sells the option to cover his exposure by a practice of dynamic hedging, which entails buying and selling a basket of other stocks to continuously even out the fluctuating risk that was incurred by selling the option. Now, that’s not a big deal when we’re talking about the possible future price of a fixed quantity of butter, eggs or pork bellies, which were the historical mainstays of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. But in 1971 the Mercantile Exchange opened the first formal market for the trading of currency futures, with a little help from a local guy named Milton Friedman. Access to this market meant that a businessman who wanted to build a factory in Hong Kong could now eliminate the tremendous danger of fluctuating currency rates by purchasing contracts to guarantee the future cost of a certain quantity of Hong Kong dollars. If the currency value suddenly shoots up, you just exercise your option. It allows you to buy a predetermined quantity of foreign money at a fixed price, so your operating expenses are covered at the expected rates. Currency risk, which had been a tremendous obstacle to international business operations, was basically eliminated. And with that, the doors of globalization were thrown open.

It’s clear that it took two other things – the collapse of the Eastern Bloc in 1989, then the first Gulf War in 1990 – to really throw those doors wide open. But such political and military considerations only show how integral the transformation was. In addition to constituting a gigantic, algorithmically powered casino, the global derivatives exchanges have served as insurance brokerages facilitating the otherwise impossibly risky business of investing capital around the world. Currency futures and a bewildering range of options, swaps, swaptions, caps, collars, etc., have made it financially possible to shift manufacturing equipment and almost any kind of labor to whatever country might offer the lowest price. And in practice, for the period from 1990 to 2008 and up to today, that has been the “China price”: the lowest number on the planet for any given category of basic manufactured goods. When you watch the containers swinging off the ship in Los Angeles, or off the trains in Chicago, you should squint to see the otherwise invisible derivative halo that surrounds them, protecting their flight through the air and cushioning their landing. If the system of derivatives breaks down, as it did in 2008, then material relations break down too, like the China trade and the US housing markets did for a few years. The system of derivatives upholds the market relations of an entire world.

Just before the crash, two economists came up with a name for that world. They called it “Chimerica” – an improbable bicontinent created by foreign capital investment, knitted together by container transport, guaranteed by derivative contracts and maintained by China’s reinvestment of its manufacturing profits in US Treasury bonds, which since the end of the Bretton Woods gold standard have been the ultimate store of value, the global reserve that props up wealth creation in the US and keeps those containers coming.[8] As you can imagine I’ve been obsessed by Chimerica since I first read about it. Rozalinda and I included it in our glossary of concepts for Southwest Corridor Northwest Passage:

Chimerica

“Term coined by the economists Ferguson and Schularick (2007). Refers to the ultimate feedback device: the capital circuit linking Chinese production to American consumption by way of global supply chains and sovereign finance. US consumption allows China to develop its factories and provide a job for millions leaving rural life, who would otherwise revolt. Chinese production, distributed cheap by big-box retailers, allows elites to compress the wages of US workers, who would otherwise revolt. US Treasury bonds allow China to keep its currency value down by exporting trade dollars back to the States to help pay for Chinese products. Is it all a mere illusion – or a two-headed monster?”

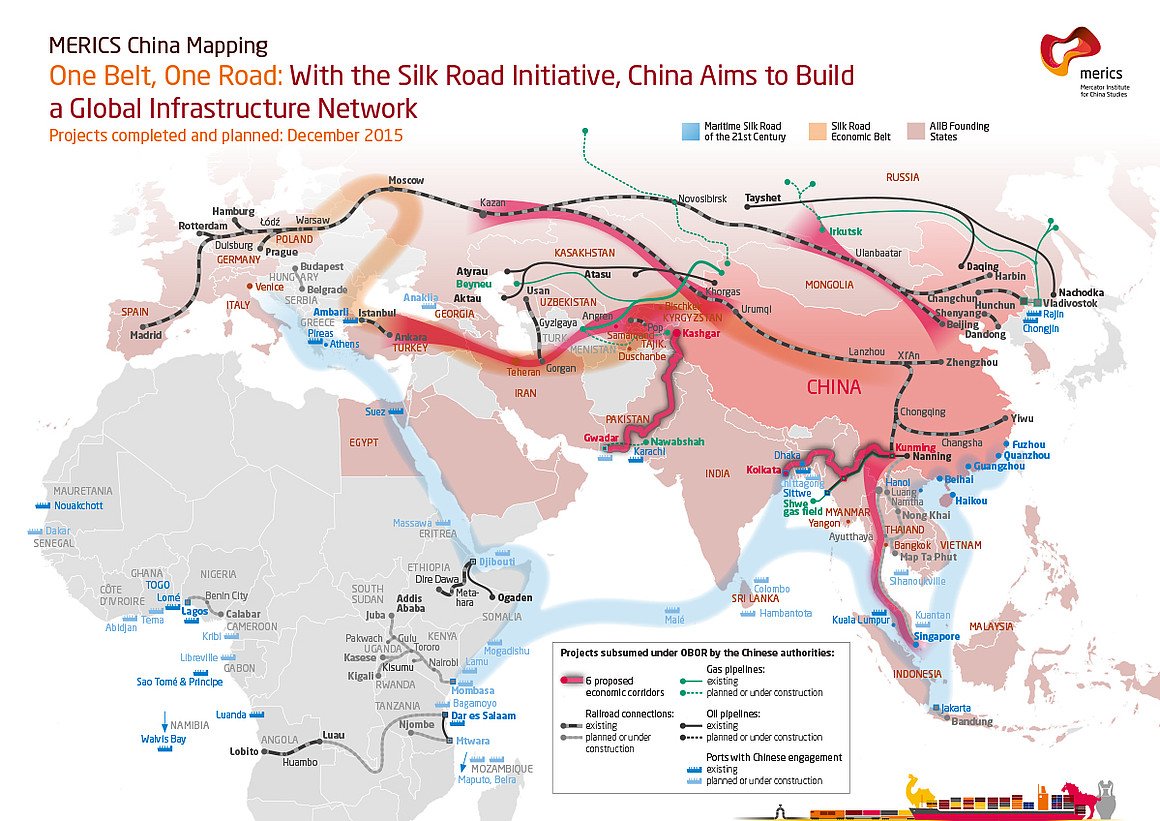

Today, we can finally answer. It’s both. On the one hand, Chimerica is an illusion: neither American wealth, nor China’s export-led growth, can be maintained by the river of cheap commodities that continues to flow into the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. You’ve seen the political revolt that the collapse of manufacturing has set off in the US, and you’ve probably heard the recent talk in US policy circles about a “New Cold War” with China. If you’re a little more curious about it, then you know that China itself has developed a replacement strategy, named “One Belt, One Road,” which consists in an effort to create its own logistical supply chains backed up by military expansionism, and thereby establish a global economic empire comparable to the one that the US set up after World War II. The current Chinese leader, Xi Jinping, describes this new growth strategy as the “China Dream,” directly repeating the old American rhetoric of the Fordist era. It’s in this sense that the illusion of Chimerica remains a two-headed monster, because it has led to the replication of the American imperial pattern, albeit with Chinese characteristics. Outliving its origins, Chimerica has resulted in a global fact of first importance: China is now the largest CO2 emitter in the world by total volume, though it still lags far behind the US in per-capita terms. It took two industrial powerhouses to melt the Arctic ice and open up the Northwest Passage.

Thus it appears that a device – the double device of containerized transport and financial derivatives – can create and destroy a world. That’s no longer the question. The question is what to do at the end of the world, now that the Chimerican industrial and financial construct which sustained such tremendous wealth creation between 1990 and 2008 is finally breaking down, revealing itself for the monster that it really is. The existential question at the end of that world is where to go now, what to aspire to, how to orient yourself, how to act, after Chimerica.

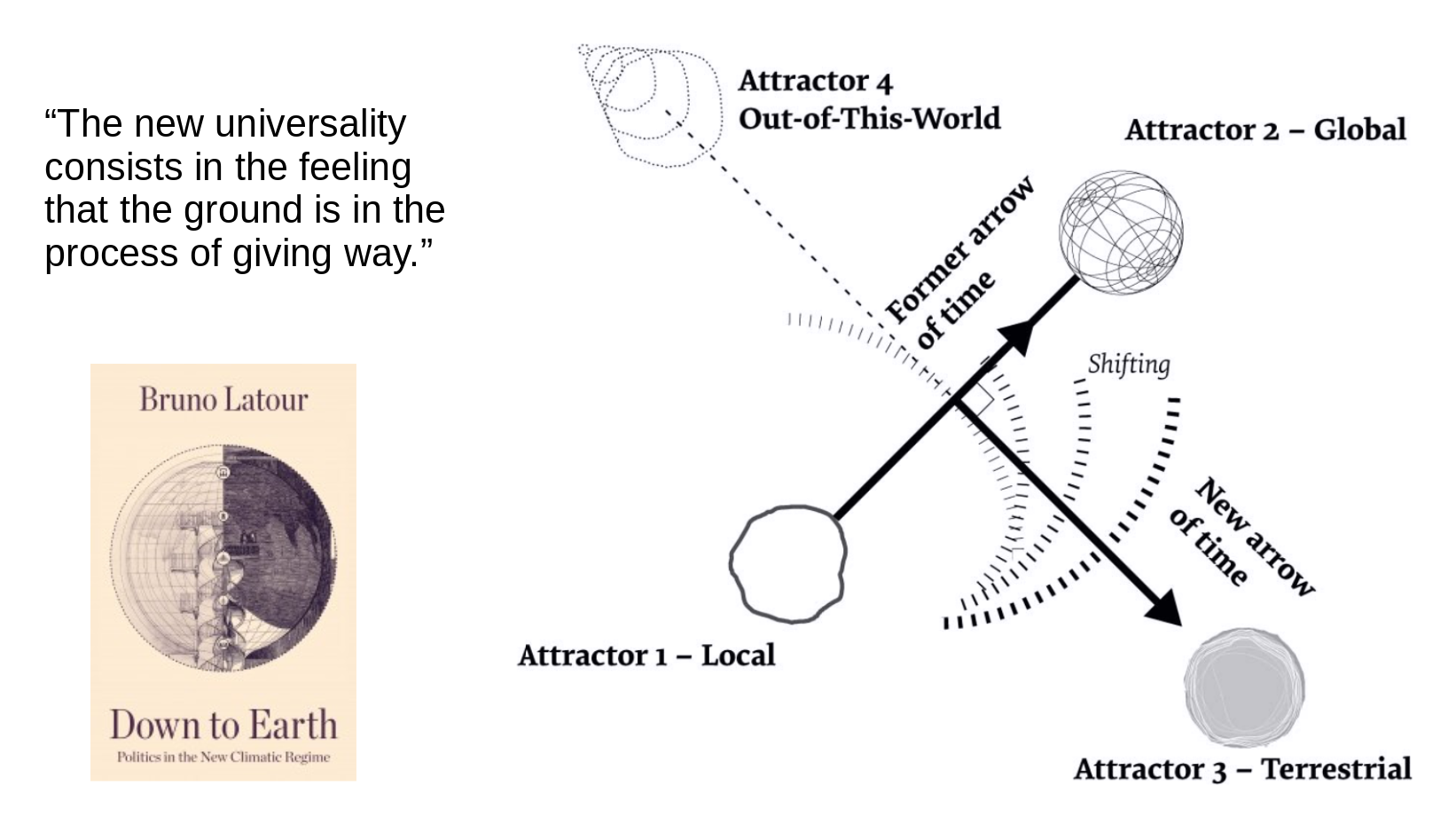

I’m making a massive claim here, which will sound overblown if it’s not held up by a powerful reference. So I’ll evoke a figure who, whatever you may have thought of him in the past, has become increasingly persuasive over the last five years. This is the anthropologist Bruno Latour, who has just published a book entitled Down to Earth.[9] What he’s asking is, Where do we touch down? Where do we land? How do we orient ourselves politically, after globalization?

Latour thinks the classic right-left divide has always been underwritten by a distinction of a very different order. He plots the distinction as a vector between two poles of attraction, the Local and the Global. Between them he places a “modernization front,” which looks forward to the full global development of capitalist industry while gesturing backward toward the straggling localities that have not yet achieved modernization. In this classic Cold War schema, the Local represents the lack of science, progress and development, or worse, it embodies a closed and defensive space of ignorance, regression, and fascism – even though it may be seen by its inhabitants as a refuge, a safe haven, a site of identity and authenticity. I think we’ve all heard localism, nativism, and identitarianism described in highly positive and highly negative ways, sometimes by the same people. The upshot is that Latour does not try to hide the fact that there’s something wrong with this picture. Instead his whole point is that the Local/Global schema is obsolete, because it has now been supplanted by another one, which grows directly out of the twin crisis of inequality and climate change.

Down to Earth presents a radical hypothesis, which Latour calls a “political fiction.” By the early 1990s the consequences of fossil-fuel development along the Local/Global axis were perfectly clear to the US ruling classes. They chose climate-change denial in full awareness that a single Earth would not be enough for their form of industrial development. By withdrawing from the Kyoto protocol and later from the Paris accords, they chose a post-truth world, which would then become an option for all other ruling classes. More importantly, they postulated the existence of an alternative reality, which they would build using the massive profits of an oligarchical economy whose spoils could be reserved for a tiny fraction of the population. So doing, they created a new attractor, a place entirely “Out of this World,” which broke the old Local/Global divide and opened up a horizon of infinite exploitation. Through this radical shift in orientation, they struck unspeakable fear into the hearts of populations. For some, it’s the fear of unchecked global warming. For others, it’s the fear that environmentalists will deny you the fruits of industry. For almost everyone, it’s the fear that the elites will grab all the fruits for themselves. The stage has been set for a massive clash of opposing fears, stoked by social-media manipulation under a cloak of denial and unconsciousness. That’s the core of contemporary politics.

Latour credits Trump with making the choice of the new attractor brutally obvious to everyone. What’s more, he says, this brutal choice revealed the existence of a second new pole, tentatively called the Terrestrial. The second pole of attraction recovers all the positive and protective attributes of the Local, but without any closure to the outside. So it’s totally different. The Terrestrial is not a world of production, but instead, of engenderment. It’s an interdependent world where life forms create conditions of possibility or impossibility for other life forms. An awareness of this world, and of the decision taken to destroy it, suddenly makes it possible – not inevitable, but possible – for the descendants of colonizers to realize what it must have been like for the colonized, when their land was suddenly ripped away from them. Your land is suddenly being fracked, fenced, polluted, and sold to the highest bidder. “The new universality,” writes Latour, “consists in feeling that the ground is in the process of giving way.”

But the point is not to go back to the Local. Instead, the Terrestrial is the place where a new ground can be disclosed – on the condition of realizing that the viability of any territory is engendered by, and depends upon, a full set of ecological relations, extending all the way to the biogeochemical cycles that maintain the balance of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Down to Earth is a compelling read, even if it’s a “political fiction.” My own theoretical fictions point in the exact same directions. The study of containerization revealed the existence of Foreign Trade Zones scattered across the continental United States. These zones are considered offshore sites for fiscal purposes, so they’re extraterritorial, and they use that offshore status to incentivize the development of new intermodal ports. As for the derivatives exchanges, in “Information’s Metropolis” I describe them as space cruisers filled with cyborg agents seeking an extraterrestrial realm for their activities. The images come directly from a science-fiction book, The Tenth Planet, written by the head of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, Leo Melamed. The book has a weird tagline on the back: “When human equals alien.” Yet as CO2 levels continued rising, the feeling of the ground slipping away beneath my own feet was more alienating than any science fiction could be. Because it was so much more intimate.

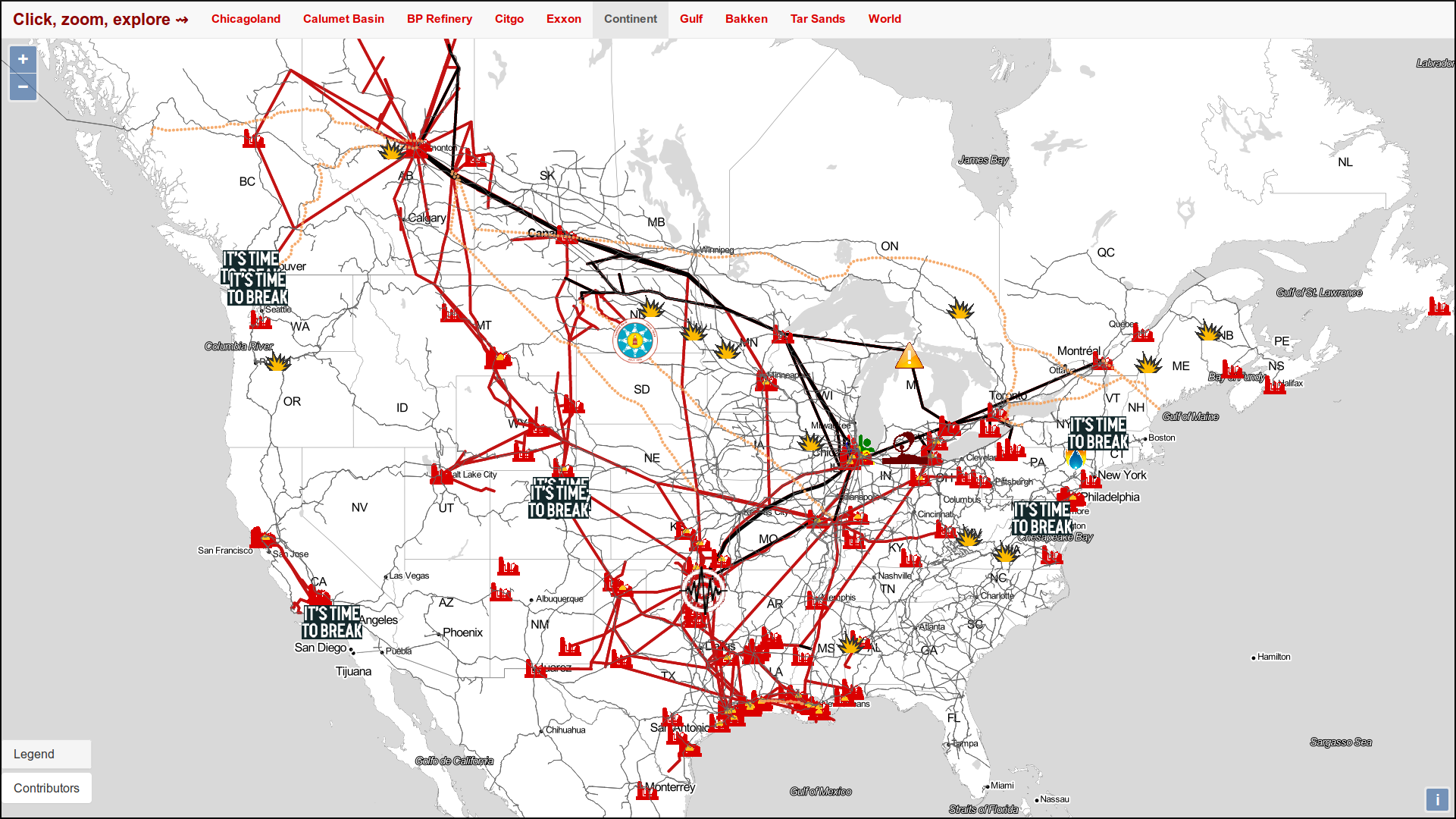

In 2015 I decided to start acting as an artist. I began a series of visual works and collaborations, combining multimedia cartography and critical writing in larger thematic shows with other artists. The first of these was about a local conflict: the pollution of Southeast Chicago neighborhoods by huge piles of petcoke, which is a byproduct of heavy oil refining. I joined this fight along with a whole group of friends and colleagues, for an activist exhibition entitled Petcoke: Tracing Dirty Energy.[10] After working with local people and exploring the oil geography by foot as well as satellite, I retraced the pipeline network that runs from Chicago to the Alberta Tar Sands. Far in the Canadian North, the oil boom set off in the early 2000s by Bush and Cheney is in the process of destroying the Athabasca River watershed. It’s extreme exploitation: mining the Earth until it looks like the Moon. I stared into my computer screen with horror as the whole forested area around the Tar Sands caught fire in August of 2016, forcing the evacuation of Fort McMurray and the man camps serving the extraction sites. It became clear that petcoke itself is a kind of cinder resulting from the intense heat of oil refining. Yet this production of cinders is the very fuel of desire, it’s the way we take flight. I gave the map the title Petropolis, City of Desire, City of Ashes – naming the universal urban condition of the climate-change era.[11]

I found it impossible to continue with the critical approach of Petropolis, which focuses entirely on energy infrastructures. Of course I included many protest figures in the map – the seeds of what has become a wildly successful resistance against oil ports and pipelines. Yet the climate-change resistance is still dwarfed by the petroleum norm. I wanted to reach beyond my activist connections, toward the mainstream. In 2016, I and ten other Chicagoans put together two collectively designed seminars for the Anthropocene Campus program of the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin. On our return we formed a group called “Deep Time Chicago.”[12] Our intent was to bring the ideas we had discussed in Berlin back home, by identifying and expressing the ways in which our city sustains the central institutions and cultural traits of the Anthropocene. At the same time, we wanted a different, disalienating contact with the local territory. The group’s initial outreach to the public has taken place through a series of events called “Walk About It,” which brings together speakers and texts for excursions to specific sites in the metropolitan area. Destinations have included a former nuclear pile, the site of an historic lumber mill, a still-functioning oil refinery, a prairie restoration project and an exquisite downtown park redesigned for the needs of urban wildlife as well as human beings. A major contribution to the group’s aesthetic was made by volunteer stewards practicing forest restoration in the tradition of the Chicago Wilderness, which has slowly grown into a federation of hundreds of organizations both public and private, devoted to the eco-regions along the southern and western shores of Lake Michigan.

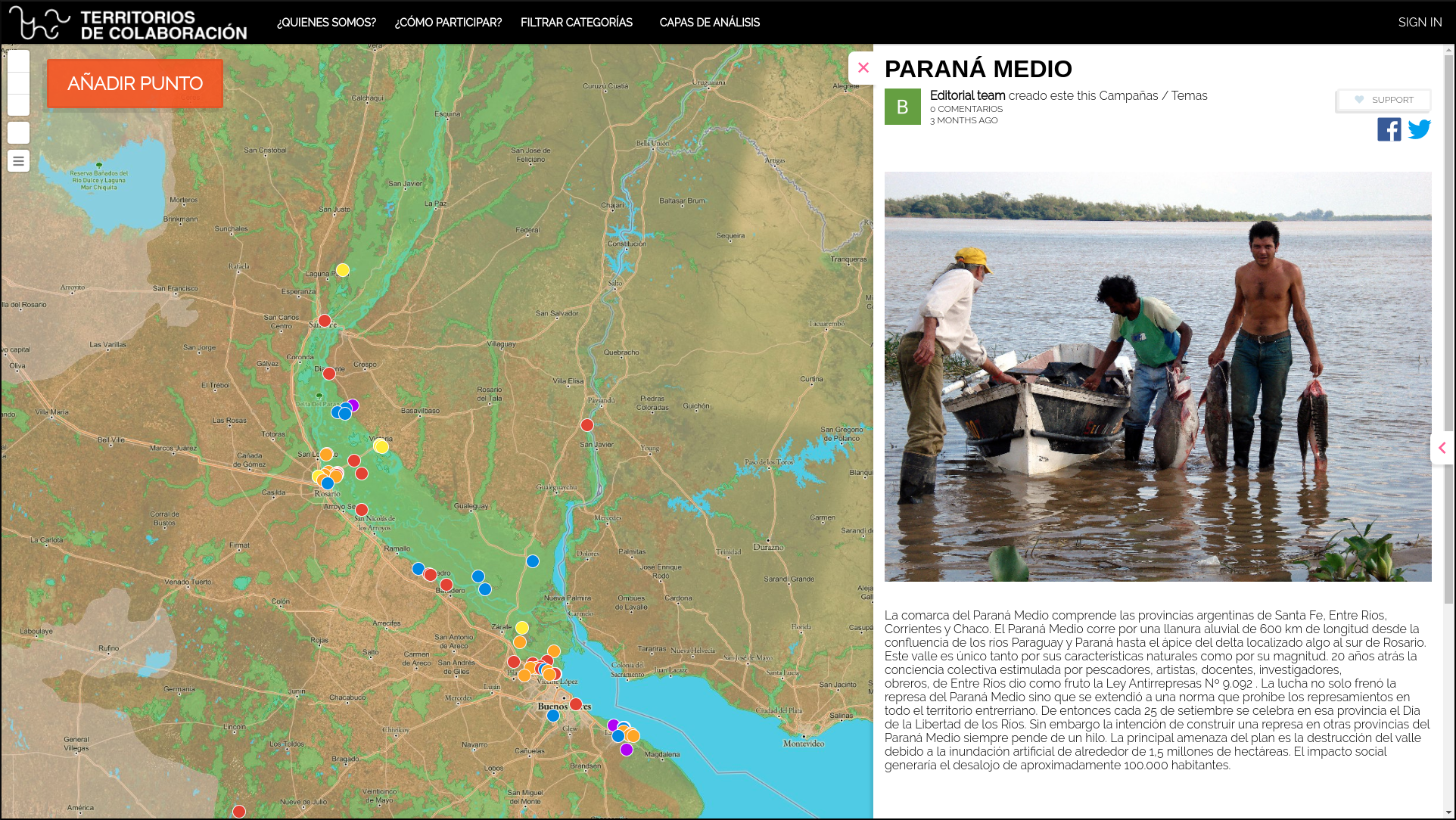

My next mapping project, done with the Argentinean artist and community activist Alejandro Meitin, is entitled Living Rivers/Ríos Vivos.[13] Each of us tried to sketch out the issues of political ecology facing humans and other species in our home watersheds, the Mississippi and Great Lakes Basins for me, the Paraná-Paraguay Basin for Alejandro. We contributed that work to The Earth Will Not Abide, a critical exhibition about industrial agriculture in the Americas.[14] What we dramatize in this exhibition are the threatened destinies of the symbiotic community of soil, when it’s exposed to the bad infinity of extractivist agriculture. The show has been restaged in Argentina in an augmented form, featuring the work of five different groups who have been exploring the islands of the Paraná River Delta.[15] The idea is to help pass a national wetlands law (“Ley de Humedales”) while at the same time inscribing territorial art as an active agency within a transnational campaign aiming to stop the entire Paraná-Paraguay wetlands system from being dried by upstream dams and drained by downstream navigation channels. Further shows are planned upriver.

Latour argues that after the failure of globalization, what matters is the defense of one’s own territory. But the defense should paradoxically be carried out in a way that opens up the territory to the relations of co-dependence that form a shared world. This requires the recognition of multiple entities as legitimate partners in a process of negotiation: species, soils, rivers, technological systems, human groups, etc. How can that negotiation be opened up on one’s own territory? That’s the real question of the present. It’s not about creating a new world, it’s about perceiving an existing one. So perception itself becomes urgent – urgent for defense. Because on the one hand, the failure of the liberal or Chimerican world order can always lead back to a zombie politics, a poisoned opposition between the Local and the Global. And on the other, even if we get over Trump, Bolsonaro, Brexit, etc., capitalism will continue bank on the infinite exploitation of a finite earth, probably through renewed economic collaboration with China.

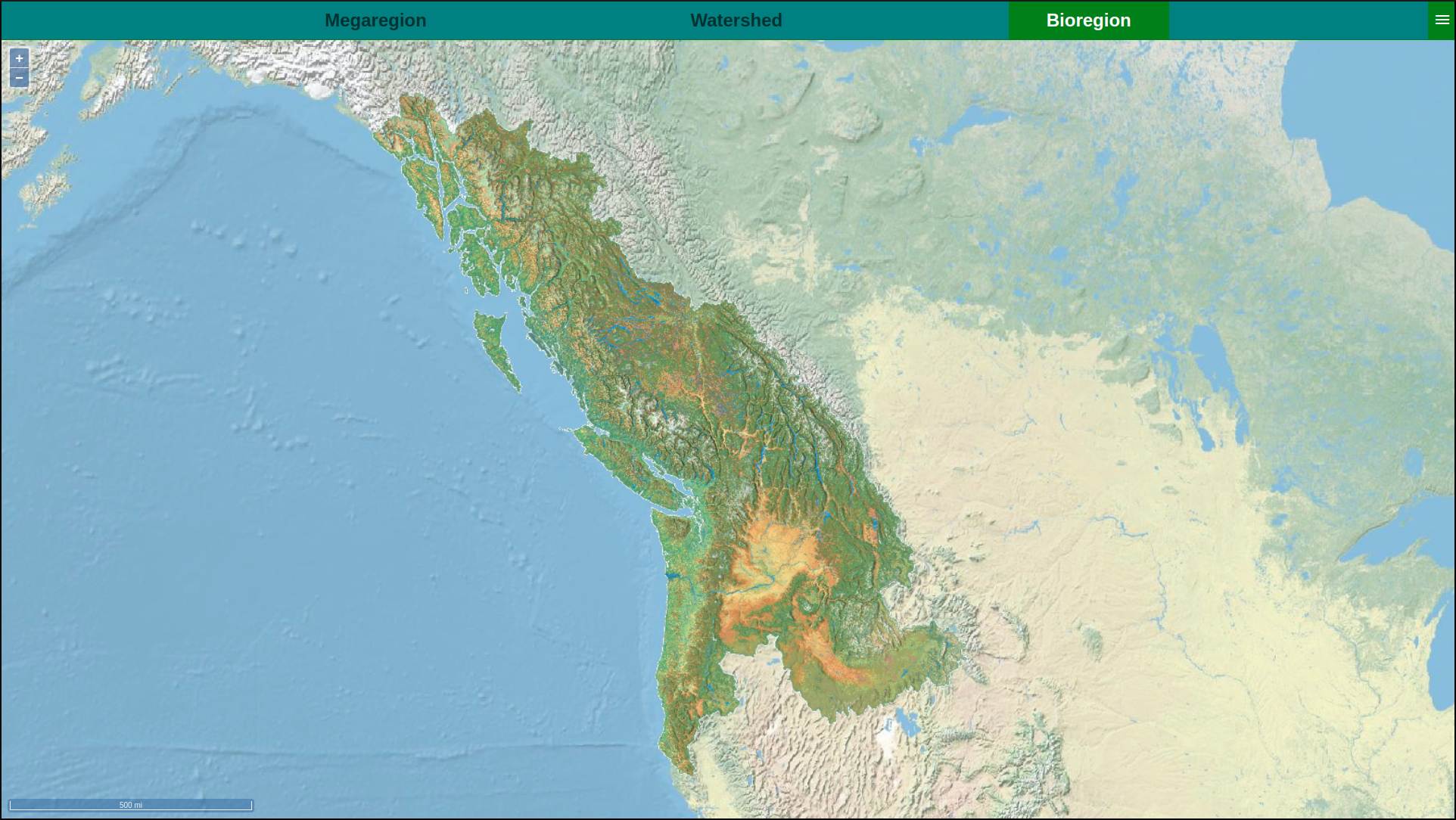

Like others, I’ve become convinced that the times require an engagement with the entangled fates of multiple species. Yet such an engagement must remain open to the full complexity of twenty-first century society. It’s about the political ecology of a bioregion, conceived as a matter of governance. To put it short, it’s about a bioregional state. There’s only one place in North America where this type of engagement is being developed at scale, within a territory conceived by many as a transnational home, where plant and animal species are widely understood to share human destinies. The place is known as the Pacific Northwest, but it’s also known to inhabitants as Cascadia. So in 2018 I began a mapping project about the bioregional state, under the title Learning from Cascadia.[16]

The project has been carried out with curator Mack McFarland and many local partners. So far it has three major aims. The first is to analyze and express the Anthropocene components of the Cascadian megaregion. These include its racial hierarchies, its urban development, its energy grid and its agricultural systems. The challenge is to describe what normally remains unconscious, and in that way to develop an implicate critique, recognizing one’s own dependency on such infrastructures. There’s a big advantage to doing that – it gives you some respect for the people who built them. When I talk about ecology, I try to do it in respect of massive generational efforts to create the good life, because that’s a basic fact of social interdependence.

The second aim is direct involvement with energy politics. We’ve done this by taking a stance in support of an activist group, Columbia Riverkeeper.[17] They’ve been fighting the installation of fossil-fuel terminals on the river, pursuing court battles to improve water conditions for returning salmon and contributing to the citizen oversight of the cleanup process at the Hanford Nuclear reservation, where plutonium was made for the US nuclear weapons program. What all this boils down to is a struggle against the most damaging legacies of the modernization front. The signature achievement of modernism in the Pacific Northwest is the region’s network of hydroelectric dams, which produce clean power at the price of destroying the riverine ecology. The struggle against them is carried out under the leadership of Indigenous tribes, who continually foreground their own relationships of co-dependence with other species. In this way a hybrid agency emerges, straddling territory and technology, sovereignty and the rights of multiple species. As you can read in that section of the map: “By helping to develop original forms of scientific expertise both within mainstream civil society and among the tribes, an expanded environmental movement could gain fresh sources of agency within the legal and administrative arenas opened up by the Endangered Species Act. The latter had the force of law, transforming citizens’ convictions and scientists’ biological opinions into instruments of tangible change… What has emerged over the last two decades, within and against the rigid machinery of the dams, are the lineaments of a new kind of governance—the upturned foundations of a future bioregional state.”

This is the key. A bioregional state is emergent whenever the survival and flourishing of non-human actors becomes an issue in formal political negotiations over land-use within a given territory. This already happens throughout the United States, but it’s an especially frequent event in the Pacific Northwest, especially under the provisions of the Endangered Species Act. That’s why one of the manifest objectives of the American ruling classes represented by Trump is to destroy the ESA. The response from the grassroots is to use it even more. In September of 2018, Columbia Riverkeeper won a crucial case at the US District Court in Seattle, where the judge mandated that the water temperatures of the Columbia and Snake rivers had to come down to ensure the survival of the salmon.[18] If the legal process is not blocked by the federal government, one likely conclusion would be the dismantling of four navigational and hydropower dams on the Lower Snake River. The constitutional machinery of law is now engaged against the legacy of modernization. If what one is after is not a utopia, but the defense of a territory, then what matters is the emergence of a bioregional state.

Now I can conclude. A bioregional state can only grow out of a broader and more diffuse culture. One of the most important things that artists and intellectuals can do is to express and analyze the constituents, forms, desires and aims of a bioregional culture. If you take this path and become part of such a culture you will have to fight for it in many ways, while remaining oriented to the possibility of a shareable world, rather than yet another civil war. The difficult thing is to fight for interdependence.

The third part of the map starts with the countercultural theory and practice of bioregionalism in the Seventies and Eighties, when founding figures like Peter Berg were on the scene. But the crucial thing is to move toward the bioregion as it is today, and to encounter its inhabitants. What comes forward are the how questions: how salmon strive to make it home and spawn; how ranchers try to ranch differently; how agriculturalists try to clean up their act; how state administrators learn to restore streams instead of damming them, and so on. One of the interviews I did was with a rancher woman, Liza Jane McAlister, whose main point is that the people living on the land care about it and for it, on the basis of long experience: their knowledge and concerns need to be included in any plan for its transformation. This means there is no formulaic device for positive territorial change: recognition and respect for singularities are the main things.

I’m also fortunate to have spent some time with the Indigenous artist Sara Siestreem, a member of the Hanis Coos band and an impressive abstract painter. In recent years she has taken up gathering and weaving as part of an effort to restore certain cultural traditions, specifically by making woven dance caps for ceremonial use. What’s challenging is the range of alliances, treaties and tribal policies that are involved: complex political arrangements for the defense of everyday life on very particular territories. It’s challenging because you have to learn to back way from what is sacred: mainstream society has no role to play in questions of ceremonial or of Indigenous sovereignty. Yet Sara does address herself to the general public. Here is what she says in the context of the show on which we collaborated, where she exhibited the plant materials she had been gathering throughout the previous year: “The next time you see these plants they will be baskets woven by Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw people,” she writes. “The education that you have gained through visiting with these plants will be embedded into those baskets. They will remember you and this time in your life. Through your witness and education, this will be a cross cultural victory over genocide.”[19]

The heart of this discussion is not a map, or a concept, or a color or a political sign. What matters in the City of Ashes is discovering how 7.6 billion people, and counting, can learn to live with each other and the rest of the Earth.

Thanks to all the collaborators named here, as well as Arne De Boever and Sebastian Olma who hosted searching public presentations of this text. While walking we ask questions.

[1] See http://southwestcorridornorthwestpassage.org/devices/definitions.

[2] Brian Holmes, “Do Containers Dream of Electric People?” in Open 21 (2011), available at www.tacticalmediafiles.net/mmbase/attachments/37547/Open21_ImMobility.pdf.

[3] See http://southwestcorridornorthwestpassage.org

[4] See https://brianholmes.wordpress.com/2009/11/06/is-it-written-in-the-stars

[5] Geissler/Sann and Holmes, Volatile Smile (Moderne Kunst Nürnberg, 2014).

[6] The text is available at http://threecrises.org/informations-metropolis.

[7] Dick Bryan and Michael Rafferty, Capitalism with Derivatives: A Political Economy of Financial Derivatives, Capital and Class (Basingstoke/New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2006).

[8] Niall Ferguson and Moritz Schularick, “‘Chimerica’ and the Global Asset Market Boom,” International Finance 10/3 (December 2007).

[9] Bruno Latour, Down to Earth (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018).

[10] See http://www.mocp.org/exhibitions/2016/07/petcoke-project.php.

[11] See http://environmentalobservatory.net/Petropolis/map.html.

[12] See http://deeptimechicago.org.

[13] See http://ecotopia.today/livingrivers/map.html and http://ecotopia.today/riosvivos/mapa.html.

[14] See http://www.regionalrelationships.org/tewna.

[15] See my short review at https://www.casarioarteyambiente.org/2019/03/12/the-earth-will-not-abide-collaborative-territories.

[16] See https://cascadia.ecotopia.today.

[17]See https://www.columbiariverkeeper.org.

[18]See two articles from the Seattle Times: https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/environment/federal-judge-orders-epa-to-protect-salmon-in-columbia-river-basin and https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/environment/washington-state-to-regulate-federal-dams-on-columbia-snake-to-cool-hot-water-check-pollution.

[19] See https://cascadia.ecotopia.today/#/bioregion/dancing.